Abstract

We use the nano-dissection capabilities of atomic force microscopy to induce structural alterations on individual virus capsids in liquid milieu. We fracture the protein shells either with single nanoindentations or by increasing the tip-sample interaction force in amplitude modulation dynamic mode. The normal behavior is that these cracks persist in time. However, in very rare occasions they self-recuperate to retrieve apparently unaltered virus particles. In this work, we show the topographical evolution of three of these exceptional events occurring in T7 bacteriophage capsids. Our data show that single nanoindentation produces a local recoverable fracture that corresponds to the deepening of a capsomer. In contrast, imaging in dynamic mode induced cracks that separate the virus morphological subunits. In both cases, the breakage patterns follow intratrimeric loci.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10867-018-9492-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Capsid, AFM, Mechanics, Fracture, Failure, Nanoindentation, Crack, Breakage

Introduction

Virus capsids have to protect, shuttle, and deliver their genome into the host [1]. In non-enveloped viruses, the protein capsid withstands a variety of physicochemical conditions along the virus cycle, including extremes of temperature and pH, osmotic shocks [2], and dehydration [3]. These abilities confer to virus shells promising applications for constructing new materials as nanocontainers [4] or 3D structures [5].

From a general point of view, virus capsids are protein shells, similar to other non-viral cages, such as microtubules [6], bacterial microcompartments [7], and vaults particles [8]. Protein shells built of repeating protein subunits whose precise arrangement and mutual interactions [9] determine their stability against destabilizing environments of chemical and physical nature [10]. Virus structure defines its stability and function in stringent environments. In this vein, structural biology techniques, such as electron microscopy (EM) and X-ray crystallography, provide high-resolution structures of protein cages [11]. However, these techniques require the average of thousands (EM) to millions (X-ray) of virus particles that suppress non-symmetrical parts from the structure, such as tails and appendages. In addition, virus preparation in vitreous ice for EM or in crystals for X-ray does not favor the study of virus dynamics in real time. To surpass these limitations, it is necessary to use methods to study individual protein assemblies in liquid milieu and in real time.

During the last years, atomic force microscopy (AFM) has emerged as a successful single-molecule approach that allows a close characterization of individual protein cages, including their nanometric topographies and their physico-chemical properties [12]. In AFM, the probe is a nanometric tip located at the end of a microcantilever which palpates virus particles weakly adsorbed on a solid surface. Although capturing virus particles on surfaces can be considered as non-physiological when viruses diffuse through a liquid environment, it is a sine qua non condition for AFM studies. Nevertheless, some aspects of virus adhesion to the host surface might be imitated by the adhesion of viruses on surfaces.

Once virus particles are immobilized, AFM obtains nanometric resolution images of individual protein shells in liquid milieu. Beyond imaging, AFM also enables the mechanical manipulation of protein cages. A common approach to manipulate a single protein cage consists of performing a nanoindentation with the AFM tip while recording the applied force. The tip, whose apex size is in the order of the curvature of the shell (~ 20 nm), approaches at the top of the particle until establishing mechanical contact. Afterwards, the tip keeps pushing, deforming the protein shell until eventually it surpasses the elastic limit [13]. The force curve of the indentation (FIC) so obtained exhibits the bending of the cantilever as a function of the Z-piezo displacement. This bending is constant during the approach and increases roughly linearly during the elastic deformation of the virus. After the elastic limit is surpassed, the cantilever bending decays abruptly in a series of steps that are associated to the way that the nanoshell yields under the applied force [14].

In addition to single indentation assay, the mere imaging process also involves application of mechanical stress to the protein cages. For example, the jumping mode consists of performing a FIC at every pixel of the image by controlling the force with the feedback loop at low force (~ 100 pN), well below the elastic limit [15]. This cyclic scanning induces the stepwise disassembly of various virus shells [16–18]. Even the variety of AFM dynamic modes may induce forces ranging from tens of pN to nN while imaging [19].

In this manuscript, we have worked with bacteriophage T7, which has an icosahedral capsid with a short non-contractile tail [20]. T7 first assembles into the prohead, which is a shell built by 415 copies of the structural protein gp10A arranged in a T = 7 icosahedral lattice [20]. The proteins are distributed in clusters of six (hexons) and five (pentons) subunits. The shell contains a dodecameric connector (gp8) at one five-fold vertice, which is linked to an inner cylinder-like core (gp14, 15 and 16) essential for infectivity [21]. Between the core and the shell there is a scaffold of multiple copies of a single protein, which is instrumental for the prohead assembly. The T7 capsid maturation process involves the packaging of 40 kb of double-stranded DNA into the prohead, the release of the scaffold, the expansion of the shell, and the incorporation of the tail proteins in the connector vertex [20]. The non-contractile tail of 18.5 nm in length assembles into the same capsid vertex where the connector is located [22]. The drastic changes within the maturation process involve a diameter increment from 51 to 60 nm, with an associated shell thinning from 4.1 to 2.3 nm [23], and entail an extensive reorganization of the interactions among all shell protein subunits [24].

Here we have used the tailless expanded capsids without DNA to induce topographical changes with both single indentation assay and amplitude modulation dynamic mode in liquids. Although self-recovery of damaged virus capsids has been theoretically predicted [25], and suggested from experiments [26], we present in this paper the first direct evidence of fracture self-healing on virus shells. They consist of three unique cases where the fractures were induced with single indentation assay and imaging with amplitude modulation dynamic mode.

Materials and methods

AFM sample preparation

Stocks of empty T7 viral particles [10] (0.5 mg/ml) were stored in TMS buffer (10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris and 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.8). A drop of 20 μl stock solution of viral particles was left on HOPG (ZYA quality NTMDT), for 30 min and washed with TMS buffer for working in liquid milieu. The cantilever was prewetted with 20 μl of buffer solution. In Fig. 1, the AFM (Nanotec Electrónica) was operated in jumping mode in liquid [15] using rectangular cantilevers RC800PSA (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with nominal spring constants of 0.05 N/m. In Figs. 2 and 3, the AFM was operated in dynamic amplitude modulation mode [27] using cantilever biolevers BL-RC150VB, as explained in the text.

Fig. 1.

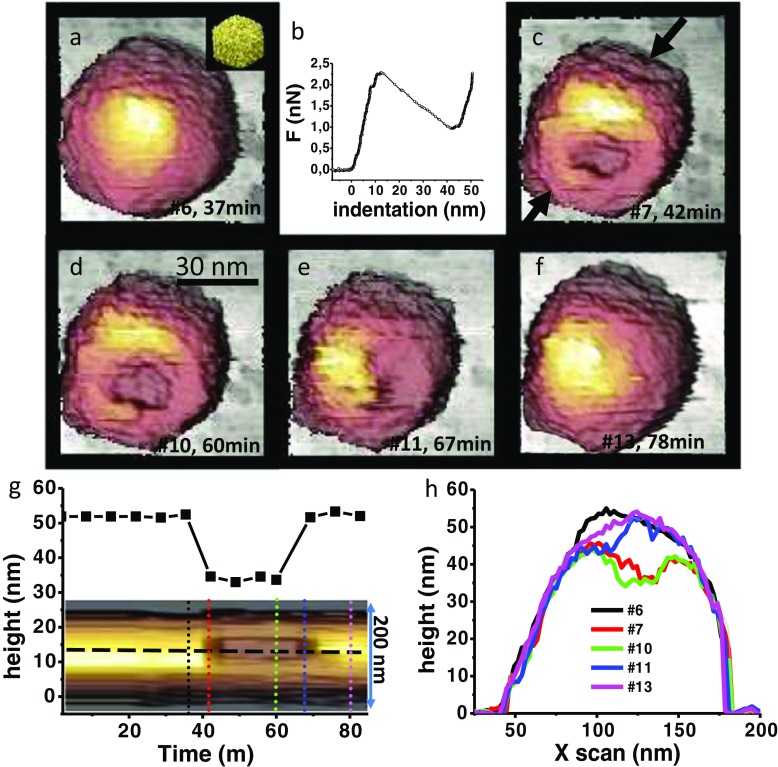

Single indentation assay, first case. a The intact T7 particle adsorbed at threefold symmetry orientating (inset). b Nanoindentation performed on the virus particle. c AFM topography right after the nanoindentation. d, e Evolution of the breakage induced by the nanoindentation. f Recovered particle. Images are labeled with the number of order and the time in minutes. g Kymograph of the breakage obtained between the black arrows of c along more than 80 min (horizontal axis). The squares graph is the profile evolution of the kymograph obtained at the horizontal dashed line on the kymograph. h Topographic profiles of the particle along time. Numbered labels indicate the AFM image and the colors correspond to those of the vertical dotted lines of the kymograph. For more explanation, see text

Fig. 2.

Amplitude modulation dynamic mode, second case. a Chart of the oscillation amplitude vs. Z-piezo approach obtained at the substrate surface. b AFM images of a T7 virus obtained at different forces that are indicated at each image. c Evolution of the profiles obtained between the black arrows of (b, upper left). For more explanation, see text

Fig. 3.

Amplitude modulation dynamic mode, third case. a Deformed T7 virus at 400 pN. b Deformed virus at 300 pN. c Recovered virus at 150 pN. d Profiles evolution along obtained between the white arrows of a. For more explanation, see text

Rendering of virus models

Virus volumes were visualized using Chimera [28] with the map emd-1810 containing the three-dimensional structure of T7 mature particles [29]. The shell architecture is labeled with pentameric vertex (white pentamers) and lattice lines (white broken lines) delineating the basic triangular faces of the T = 7 shell of the virus. Black broken lines follow the pentamer to pentamer geometry to help correlation of AFM and cryo-microscopy images. Major shell protein monomers (gp10) are outlined in red to mark the positions around threefold axis (trimers at center of basic triangular faces), and fivefold axis (pentamers).

Results

In the first case (Fig. 1), we present a T7 capsid adsorbed with a three-fold symmetry axis orientation (Fig. 1a, inset). We imaged this particle in jumping mode using Olympus cantilevers OML-RC of 0.05 N/m at ~100 pN. After obtaining six images, we performed a FIC, whose nanoindentation (Fig. 1b) deforms the virus shell linearly until the elastic limit at a force of ~2.25 nN. Afterwards, the steep step indicates that the particle has been most likely broken by the AFM tip. Subsequently, the FIC exhibits an infinite slope, meaning that the sample is infinity stiff compared to the cantilever spring constant. This phenome indicates that the tip reached the surface of the substrate after ~50 nm of indentation from the tip–virus contact. The virus topography imaged right after the FIC (Fig. 1c) shows a conspicuous fracture at the center of the capsid. The virus particle was reiteratively imaged (Supplementary Information –SI- movie SM1), up to 13 times, (7 min per frame) at 100 pN of imaging force. Figure 1d shows the topography #10, the fourth after breakage, and shows certain evolution of the fracture perimeter. In Fig. 1e, the perimeter and position of the fracture evolves to the right of the particle. Finally, the topography of Fig. 1f demonstrates that the fracture recovered. The inset of Fig. 1f shows the kymograph of the profile indicated by the black arrows of Fig. 1c along 13 images during 90 min. The horizontal dashed black line points to the temporal evolution depicted by the squares chart, spanning about 90 min. This graph illustrates that the fracture reached a depth of about 20 nm that recovered after four images and 25 min. Figure 1h portrays the individual profiles indicated by the dotted vertical lines of the Fig. 1g kymograph. Each profile depicts the profile to each AFM image #6, #7, #10, #11, and #13 with the corresponding color code of the Fig. 1g inset. We observed this recovery event after nanoindentation with a FIC in one case out of 50 particles under similar conditions.

In the next cases, we operated the AFM in dynamic mode amplitude modulation in liquid [27]. In this imaging methodology, the cantilever is oscillated at its resonance frequency while imaging the surface by controlling the amplitude with the feedback loop. This means that the feedback controls the elongation of the Z-piezo to keep the amplitude constant at certain value chosen by the user. Here we oscillated Olympus cantilevers BL-RC150VB A lever (0.03 N/m) at ~37 KHz with a free amplitude of 15 nm (Fig. 2a). This chart shows how the amplitude decreases as the cantilever is approached to the surface of the substrate. The tip–surface interaction increases as the amplitude decreases, since the oscillation energy dissipates as the tip hits the surface at each oscillation [27]. In this case, the feedback loop is locked at an amplitude of 10 nm, which means that the cantilever lost 15 nm – 10 nm = 5 nm of oscillation that is dissipated in the surface. Therefore, the average applied force to the surface is 5 nm × 0.03 nN/nm = 0.150 nN [27]. In these conditions, we imaged a T7 capsid (Fig. 2b, top left), which was oriented at the fivefold symmetry axis and shows a height (Fig. 2c, black) compatible with the particle size [20]. Afterwards, we decreased the feedback amplitude to 5 nm, which corresponds to an imaging force of ~300 pN (Fig. 2a). Under these conditions, the T7 particle (Fig. 2b, up right) exhibited a conspicuous crack at the very top (Fig. 2c, green). This fracture evolves (Fig. 2b, down left) upon increasing the feedback amplitude to set the average imaging interaction in ~300 pN (Fig. 2c, red). When setting the average imaging force to the initial value (150 pN), the fracture recovers (Fig. 2b, down right) and the topographical profile restores to the initial one (Fig. 2c, blue). We arranged the topographical AFM images in a movie including eight frames (SI, movie SM2) where it is possible to appreciate the dynamics of the recovery during 5 min.

In Fig. 3 we present the third T7 particle with a self-healing fracture. In this case, we started the experiment by applying an imaging force (400 pN), which resulted in a deformed T7 particle (Fig. 3a) exhibiting evident cracks at the top. Subsequently, we decreased the force value to 300 pN and the appearance of the fracture changed (Fig. 3b). By reducing the imaging force up to 150 pN, the virus particle revealed a fivefold symmetry axis orientation without any trace of deformation or fracture (Fig. 3c). Figure 3d depicts the profiles of the virus at the slice indicated by the white arrows of Fig. 3a. These profiles illustrate that the fracture was larger at high imaging force (400 pN, black) than a low force (150 pN, blue). The red chart shows an intermediate stage (Fig. 3b) of the fracture at 300 pN. We arranged the topographical AFM images including five frames in a movie (SO, movie SM3) where the dynamics of the recovery can be appreciated during 3 min. In amplitude modulation dynamic mode, we observed these two recovery cases in two cases out of 50 particles under similar conditions.

Discussion

Theoretical simulations predict that protein shells may buckle under mechanical stress [30, 31], recovering back after the AFM tip releases the particle. In the experimental side, AFM allows identifying any structural change by monitoring the protein shell before and after the FIC. It has been shown many times that nanoindentations surpassing the elastic limit induce permanent breakages on the shell structure [6, 10, 32–35]. However, other times FIC data showing a clear elastic limit do not induce any observable alteration of the shell structure. In this case, it is difficult to attribute univocally the origin of these force steps to reversible buckling [26], fractures that recover, tip slip off, etc. [25]. In the specific case of vault particles, very often no structural alteration could be observed after the nanoindentations [36]. Nevertheless, when fractures were visible after nanoindentation, some of them recovered after a few minutes. This effect has also been observed in microtubules [13] and HIV protein monolayers [37]. Here we report the first experimental evaluation of self-recovery after breakage in virus shells. A common feature to the three cases presented here is that fractures appear as highly dynamic features (SI, movies SM1, SM2, SM3), which are in contrast with the static vision of virus fractures presented in previous experiments [32]. This dynamics is likely related to the virus shells immersion in liquid, where Brownian diffusion moves the proteins back and forth until recovery takes place. In spite of this dynamics, it is possible to tackle a structural analysis of the fractures in a qualitative way (see Materials and methods). We draw in blue color the border of the fracture corresponding to the topography of Fig. 1d (Fig. 4a, left) and superimpose it onto the cryo-EM virus structure (Fig. 4a, right) [29] with the same orientation as the initial AFM topography (Fig. 1a). The fracture lines in this case follow closely the outline of a hexamer of the T7 shell. This hexon collapse links the threefold symmetry centers of neighboring trimeric subunits (building the basic triangular unit of the T7 shell lattice). This behavior of the hexon is different from the irreversible breakage behavior in other cases: in phi29, the irreversible fracture patterns followed lattice lines, suggesting that the trimers building the triangular shell unit were reacting as a mechanical ensemble [32]. In contrast, the reversible fracture in T7 capsid involves a hexon collapse, thus distorting the threefold arrangement but leaving the trimeric interactions ready for recovery, yielding the re-organization of the shell main interaction by loading the subunits building the hexamer in proper place. In the second case, the fracture lines (Fig. 4b, left) also distort the threefold arrangement (Fig. 4b, right) and leave the trimeric interactions ready for recovery. In the third case, the deformed virus capsid (Fig. 3a) appears highly distorted in comparison with the recovered structure (Fig. 3c). Although this fact hampers the comparison between both structures, the deformed case (Fig. 4c, left) is compatible with the penton deepening. Thus, this case would also involve the distortion of the threefold arrangements of the penton proteins (Fig. 4c, right). This common feature of the three cases might explain why recovery events are scarce, as they reflect an exceptional distortion of the basic shell interaction forces, which are stronger around the threefold centers. In these peculiar cases, the rapid recovery of the trimeric interactions restores the shell interaction patterns by recovering the standard shell arrangement inserting the trimeric subunits in their original position.

Fig. 4.

Structural analysis of breakages. a Left, breakage pattern of the first case. Right, breakage pattern superimposed to T7 cryo-EM structure [29] (Materials and methods). b Left, breakage pattern of the second case. Right, breakage pattern superimposed to T7 cryo-EM structure [29]. c Left, breakage pattern of the third case. Right, breakage pattern superimposed to T7 cryo-EM structure [29]. For more explanation, see text

It is worth discussing now the physical issues of these fractures. In the first case (Fig. 1), the nanoindentation produced an extensive breakage where some portion of the shell appears removed. Actually, the profile #10 of Fig. 1h shows a plateau at the broken region that implies the tip reached the bottom of the fracture. The height of this crack (~ 35 nm) indicates that it is it is not the inner wall of the virus capsid, but the hexon that sank inside the shell. Another important feature is that the FIC (Fig. 1b) exhibits an indentation of about 50 nm, from the tip–virus initial mechanical contact, which is about the original height of the virus. However, Fig. 1g and h show that the fracture has a depth of 20 nm. This fact could indicate that although the virus was initially deformed 50 nm, it performs a partial recovery of 30 nm before image #7 (Fig. 1c) was taken. Another alternative explanation is the different ways that the capsid is deformed between a single FIC and jumping mode, aimed for breaking and imaging the capsid, respectively. While in a single force indentation curve (FIC) the Z-piezo elongates a predefined length without controlling the force, in jumping mode the tip indents the sample until a certain force is reached. Thus, it is possible that the maximum indentation achieved at FIC does not coincide with the depth of the crack observed at the subsequent image. In the second case (Fig. 2), fractures are similar to cracks, suggesting that proteins have been separated between them but not removed. The third case (Fig. 3) is too complicated to dare any speculation, although its dynamics (SI supplemental movie SM3) might indicate the recovery of the penton. It is interesting to observe that when imaging in dynamic mode, the breakages depths just reached ~3 nm and ~6 nm for the second (Fig. 2c) and the third (Fig. 3d) cases, respectively. These fracture depths are in big contrast to the nanoindentation case, whose value is about 20 nm (Fig. 1g). This effect may be related to the deformation methodology. While in the first case the nanoindentation affects locally to the hexon during 1 seconds, in dynamic mode cases, the tip established contact with the virus shell 37,000 times per second. Since the tip was scanning the virus for 36 seconds per image, it established mechanical contact with the virus 1.3 × 106 times per topography. We might speculate that this would produce a global deformation of the virus inducing cracks instead of extensive breakages, as in the single indentation case.

Conclusions

In this manuscript we report for the first time the direct visualization of fracture self-recoveries in virus shells. The detections of these breakage restorations are very rare events and we report only three cases within 100 particles. However, we are not aware of any artifact that could produce these results. Currently, there is no control about which kind of breakage will be restored or not, although as a rule of thumb we could say that fractures and cracks should be tiny enough to not alter the original shape of the virus shell. Although we experimentally demonstrate that self-recovery of virus shells happens, the statistical significance is very low and much more research is needed to control and understand under which conditions the virus protein shell self-recovery takes place.

Electronic supplementary material

(AVI 15141 kb)

(AVI 2263 kb)

(AVI 1242 kb)

Acknowledgements

PJP thanks FIS2014-59562-R, FIS2017-89549-R, FIS2015-71108-REDT from Fundación BBVA and “María de Maeztu” Program for Units of Excellence in R&D (MDM-2014-0377). JLC and CC acknowledge “Severo Ochoa” Centres of Excellence and JLC to BFU2014-54181.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10867-018-9492-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Pedro J. de Pablo, Email: p.j.depablo@uam.es

Mercedes Hernando-Pérez, Email: mercedes.hernando@cnb.csic.es.

José L. Carrascosa, Email: jlcarras@cnb.csic.es

References

- 1.Flint SJ, Enquist LW, Racaniello VR, Skalka AM. Principles of Virology. Washington DC: ASM Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cordova A, Deserno M, Gelbart WM, Ben-Shaul A. Osmotic shock and the strength of viral capsids. Biophys. J. 2003;85(1):70–74. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74455-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carrasco C, Douas M, Miranda R, Castellanos M, Serena PA, Carrascosa JL, Mateu MG, Marques MI, de Pablo PJ. The capillarity of nanometric water menisci confined inside closed-geometry viral cages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106(14):5475–5480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810095106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lucon J, Qazi S, Uchida M, Bedwell GJ, LaFrance B, Prevelige PE, Jr, Douglas T. Use of the interior cavity of the P22 capsid for site-specific initiation of atom-transfer radical polymerization with high-density cargo loading. Nat. Chem. 2012;4(10):781–788. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uchida, M., McCoy, K., Fukuto, M., Yang, L., Yoshimura, H., Miettinen, H.M., LaFrance, B., Patterson, D.P., Schwarz, B., Karty, J.A., Prevelige, P.E., Lee, B., Douglas, T.: Modular self-assembly of protein cage lattices for multistep catalysis. ACS Nano (2017). 10.1021/acsnano.7b06049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.de Pablo PJ, Schaap IAT, MacKintosh FC, Schmidt CF (2003) Deformation and collapse of microtubules on the nanometer scale. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91(9), 098101 (2003). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.098101 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Snijder J, Kononova O, Barbu IM, Uetrecht C, Rurup WF, Burnley RJ, Koay MS, Cornelissen JJ, Roos WH, Barsegov V, Wuite GJ, Heck AJ. Assembly and mechanical properties of the cargo-free and cargo-loaded bacterial Nanocompartment Encapsulin. Biomacromolecules. 2016;17(8):2522–2529. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Llauro A, Guerra P, Kant R, Bothner B, Verdaguer N, de Pablo PJ. Decrease in pH destabilizes individual vault nanocages by weakening the inter-protein lateral interaction. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:34143. doi: 10.1038/srep34143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zlotnick A. Are weak protein-protein interactions the general rule in capsid assembly? Virology. 2003;315(2):269–274. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6822(03)00586-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernando-Perez M, Pascual E, Aznar M, Ionel A, Caston JR, Luque A, Carrascosa JL, Reguera D, de Pablo PJ. The interplay between mechanics and stability of viral cages. Nano. 2014;6(5):2702–2709. doi: 10.1039/c3nr05763a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker TS, Olson NH, Fuller SD. Adding the third dimension to virus life cycles: three-dimensional reconstruction of icosahedral viruses from cryo-electron micrographs. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999;63(4):862–922. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.4.862-922.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreno-Madrid F, Martin-Gonzalez N, Llauro A, Ortega-Esteban A, Hernando-Perez M, Douglas T, Schaap IA, de Pablo PJ. Atomic force microscopy of virus shells. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017;45(2):499–511. doi: 10.1042/BST20160316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaap IAT, Carrasco C, de Pablo PJ, MacKintosh FC, Schmidt CF. Elastic response, buckling, and instability of microtubules under radial indentation. Biophys. J. 2006;91(4):1521–1531. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.077826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Pablo, P.J.: Atomic force microscopy of virus shells. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. (2017). 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.08.039 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Ortega-Esteban A, Horcas I, Hernando-Perez M, Ares P, Perez-Berna AJ, San Martin C, Carrascosa JL, de Pablo PJ, Gomez-Herrero J. Minimizing tip-sample forces in jumping mode atomic force microscopy in liquid. Ultramicroscopy. 2012;114:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ortega-Esteban, A., Perez-Berna, A.J., Menendez-Conejero, R., Flint, S.J., Martin, C.S., de Pablo, P.J.: Monitoring dynamics of human adenovirus disassembly induced by mechanical fatigue. Sci. Rep. 3 (2013). 10.1038/srep01434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Hernando-Pérez M, Lambert S, Nakatani-Webster E, Catalano CE, de Pablo PJ. Cementing proteins provide extra mechanical stabilization to viral cages. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4520. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mertens J, Casado S, Mata CP, Hernando-Perez M, de Pablo PJ, Carrascosa JL, Caston JR. A protein with simultaneous capsid scaffolding and dsRNA-binding activities enhances the birnavirus capsid mechanical stability. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:13486. doi: 10.1038/srep13486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia R, Perez R. Dynamic atomic force microscopy methods. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2002;47(6-8):197–301. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5729(02)00077-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agirrezabala X, Martin-Benito J, Caston JR, Miranda R, Valpuesta M, Carrascosa JL. Maturation of phage T7 involves structural modification of both shell and inner core components. EMBO J. 2005;24(21):3820–3829. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.García LR, Molineux IJ. Transcription-independent DNA translocation of bacteriophage T7 DNA into Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178(23):6921–6929. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6921-6929.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cuervo A, Pulido-Cid M, Chagoyen M, Arranz R, González-García VA, Garcia-Doval C, Castón JR, Valpuesta JM, van Raaij MJ, Martín-Benito J, Carrascosa JL. Structural characterization of the bacteriophage T7 tail machinery. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288(36):26290–26299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.491209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrascosa JL, Agirrezabala X, Velazquez-Muriel JA, Gomez-Puertas P, Scheres SHW, Carazo JM. Quasi-atomic model of bacteriophage T7 procapsid shell: insights into the structure and evolution of a basic fold. Structure. 2007;15(4):461–472. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monera OD, Kay CM, Hodges RS. Protein denaturation with guanidine-hydrochloride or urea provides a different estimate of stability depending on the contributions of electrostatic interactions. Protein Sci. 1994;3(11):1984–1991. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560031110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aznar M, Luque A, Reguera D. Relevance of capsid structure in the buckling and maturation of spherical viruses. Phys. Bio. 2012;9(3):036003. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/9/3/036003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Voros Z, Csik G, Herenyi L, Kellermayer MSZ. Stepwise reversible nanomechanical buckling in a viral capsid. Nanoscale. 2017;9(3):1136–1143. doi: 10.1039/C6NR06598H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Putman CAJ, Vanderwerf KO, Degrooth BG, Vanhulst NF, Greve J. Tapping mode atomic-force microscopy in liquid. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1994;64(18):2454–2456. doi: 10.1063/1.111597. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25(13):1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ionel A, Velazquez-Muriel JA, Luque D, Cuervo A, Caston JR, Valpuesta JM, Martin-Benito J, Carrascosa JL. Molecular rearrangements involved in the capsid Shell maturation of bacteriophage. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286(1):234–242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.187211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vliegenthart GA, Gompper G. Mechanical deformation of spherical viruses with icosahedral symmetry. Biophys. J. 2006;91(3):834–841. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.081422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klug WS, Bruinsma RF, Michel JP, Knobler CM, Ivanovska IL, Schmidt CF, Wuite GJL. Failure of viral shells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;97(22):228101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.228101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ivanovska IL, Miranda R, Carrascosa JL, Wuite GJL, Schmidt CF. Discrete fracture patterns of virus shells reveal mechanical building blocks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108(31):12611–12616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105586108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snijder J, Uetrecht C, Rose RJ, Sanchez-Eugenia R, Marti GA, Agirre J, Guerin DM, Wuite GJ, Heck AJ, Roos WH. Probing the biophysical interplay between a viral genome and its capsid. Nat. Chem. 2013;5(6):502–509. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ortega-Esteban A, Condezo GN, Perez-Berna AJ, Chillon M, Flint SJ, Reguera D, San Martin C, de Pablo PJ. Mechanics of viral chromatin reveals the pressurization of human adenovirus. ACS Nano. 2015;9(11):10826–10833. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b03417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Llauro A, Schwarz B, Koliyatt R, de Pablo PJ, Douglas T. Tuning viral capsid nanoparticle stability with symmetrical morphogenesis. ACS Nano. 2016;10(9):8465–8473. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b03441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Llauro A, Guerra P, Irigoyen N, Rodriguez JF, Verdaguer N, de Pablo PJ. Mechanical stability and reversible fracture of vault particles. Biophys. J. 2014;106(3):687–695. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valbuena A, Mateu MG. Quantification and modification of the equilibrium dynamics and mechanics of a viral capsid lattice self-assembled as a protein nanocoating. Nano. 2015;7(36):14953–14964. doi: 10.1039/c5nr04023j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(AVI 15141 kb)

(AVI 2263 kb)

(AVI 1242 kb)