Abstract

Shiga toxin (Stx) is the key virulent factor in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC). To date, three Stx1 subtypes and seven Stx2 subtypes have been described in E. coli, which differed in receptor preference and toxin potency. Here, we identified a novel Stx2 subtype designated Stx2h in E. coli strains isolated from wild marmots in the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau, China. Stx2h shares 91.9% nucleic acid sequence identity and 92.9% amino acid identity to the nearest Stx2 subtype. The expression of Stx2h in type strain STEC299 was inducible by mitomycin C, and culture supernatant from STEC299 was cytotoxic to Vero cells. The Stx2h converting prophage was unique in terms of insertion site and genetic composition. Whole genome-based phylo- and patho-genomic analysis revealed STEC299 was closer to other pathotypes of E. coli than STEC, and possesses virulence factors from other pathotypes. Our finding enlarges the pool of Stx2 subtypes and highlights the extraordinary genomic plasticity of E. coli strains. As the emergence of new Shiga toxin genotypes and new Stx-producing pathotypes pose a great threat to the public health, Stx2h should be further included in E. coli molecular typing, and in epidemiological surveillance of E. coli infections.

Introduction

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) represents an E. coli pathotype producing at least one of Shiga toxins (Stxs), Stx1 and Stx2. STEC has emerged as an important enteric pathogen causing human gastrointestinal disease, ranging from sporadic cases, diarrhea, hemorrhagic colitis (HC), to hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) worldwide1. Stx, the primary virulence factor of STEC, is an AB5 toxin. The A subunit injures the eukaryotic ribosome, and halts protein synthesis in target cells. The B pentamer binds to the cellular receptor, globotriaosylceramide, Gb3, found primarily on endothelial cells2. Stx1 and Stx2, sharing 56% amino acid sequence similarity, are distinguishable based on the inability of antisera to provide cross neutralization3. Several Stx1/Stx2 subtypes and variants have been reported4. Different Stx subtypes have been reported to vary in receptor preference and toxin potency5. The stx genes are encoded in heterogeneous lambdoid prophages (Stx phages), which are highly mobile genetic elements in the genome. Stx phages are involved in horizontal genes transfer, thus likely causing the dissemination of stx genes among E. coli strains. The loss of stx genes has also been observed during subculture6.

The intestinal tract of ruminants, particularly cattle, have been regarded as the primary reservoir of STECs7, which normally does not cause any disease in animals. STEC have also been recovered from other domestic animals, such as sheep, goats, pigs, cats and dogs8, as well as wild animals9,10. In our previous studies, we depicted the molecular characteristics of STEC in domestic and wild animals, foodstuffs of animal origin, as well as humans in China, which demonstrated dramatically diversity11–15. Notably, we systematically investigated the prevalence of STEC in wild animals exclusively residing on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau, China, an extremely harsh wild environment with elevations between 3500 and 5500 meters above sea level, including yak, pika, antelope and marmot11,13,14,16. Our previous studies enlarged the reservoir host range of STECs and further expand the knowledge of their genetic and phenotypic diversity. Genomic analysis revealed that the marmot E. coli isolates, including STECs carried a mixed virulence gene pool, and hybrid pathogenic forms were found in different pathotypes of marmot E. coli isolates16.

Hereafter, we investigated STEC isolates in intestinal contents of the healthy wild Marmota himalayana, in the same wild environment, but sampled in different year from our previous study. Here, we emphasized the identification and characterization of a novel Stx2 subtype from marmot STEC strains.

Results

Prevelance of STEC in M. himalayana

Two hundred marmot intestinal content samples were collected from three sites of Tibet plateau area, and six STEC strains were isolated, giving a culture positive rate of 3%. Among the six stx2-positive isolates, four of them (STEC293, STEC294, STEC295, and STEC299) were from marmots sampled at two sites (Table 1). Further characterization showed that these four isolates shared same serotype O102:H18, and sequence type (ST3693) (Table 1). Except for stx2 gene, the four strains only possessed adhensin related gene paa among the seven main STEC virulence-related genes detected by PCR. The other two isolates, STEC296 and STEC297, belonging to the serotype Orough:H8 and O168:H14, had different virulence gene profiles and sequence types (Table 1).

Table 1.

STEC isolates recovered from intestinal contents of Marmota himalayana.

| Isolates | Serotype | stx subtype | Virulence genes* | Sequence type | Site (above m.s. l, latitude/longitude) | Sampling time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STEC293 | O102:H18 | 2h | paa | 3693 | Zhongdaxiang (3599 m, 33°13′/97°01′) | 2013-07-29 |

| STEC294 | O102:H18 | 2h | paa | 3693 | Dezhuotan (3025 m, 33°03′/97°11′) | 2013-08-02 |

| STEC295 | O102:H18 | 2h | paa | 3693 | Dezhuotan (3025 m, 33°03′/97°11′) | 2013-08-03 |

| STEC299 | O102:H18 | 2h | paa | 3693 | Dezhuotan (3025 m, 33°03′/97°11′) | 2013-08-02 |

| STEC296 | Orough:H8 | 2a | ehxA, saa | 26 | Dedacun (3625 m, 33°06′/97°08′) | 2013-08-06 |

| STEC297 | O168:H14 | 2g | astA, saa | 718 | Dedacun (3625 m, 33°06′/97°08′) | 2013-08-07 |

*Virulence genes tested include eae, ehxA, efa1, saa, paa, toxB, and astA, among which only PCR-positive gene is listed for each isolate.

Identificaition of a novel Stx2 subtype in STEC strains of Marmot origin

Among six STEC strains isolated in this study, two of them carried stx2 gene that can be subtyped by the PCR-based method, one carried stx2a, and the other harbored stx2g (Table 1). However, the stx2 carried by other four isolates (STEC293, STEC294, STEC295, and STEC299) failed to give amplicon using stx2-subtypes specific primers. The full length stx2 genes of the four isolates was then amplified. Sequence analysis revealed the stx2 genes in these four isolates were identical.

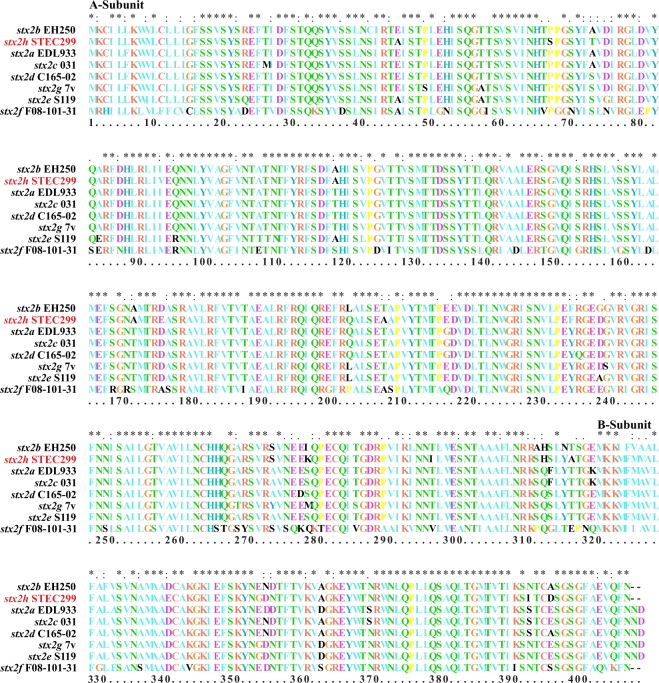

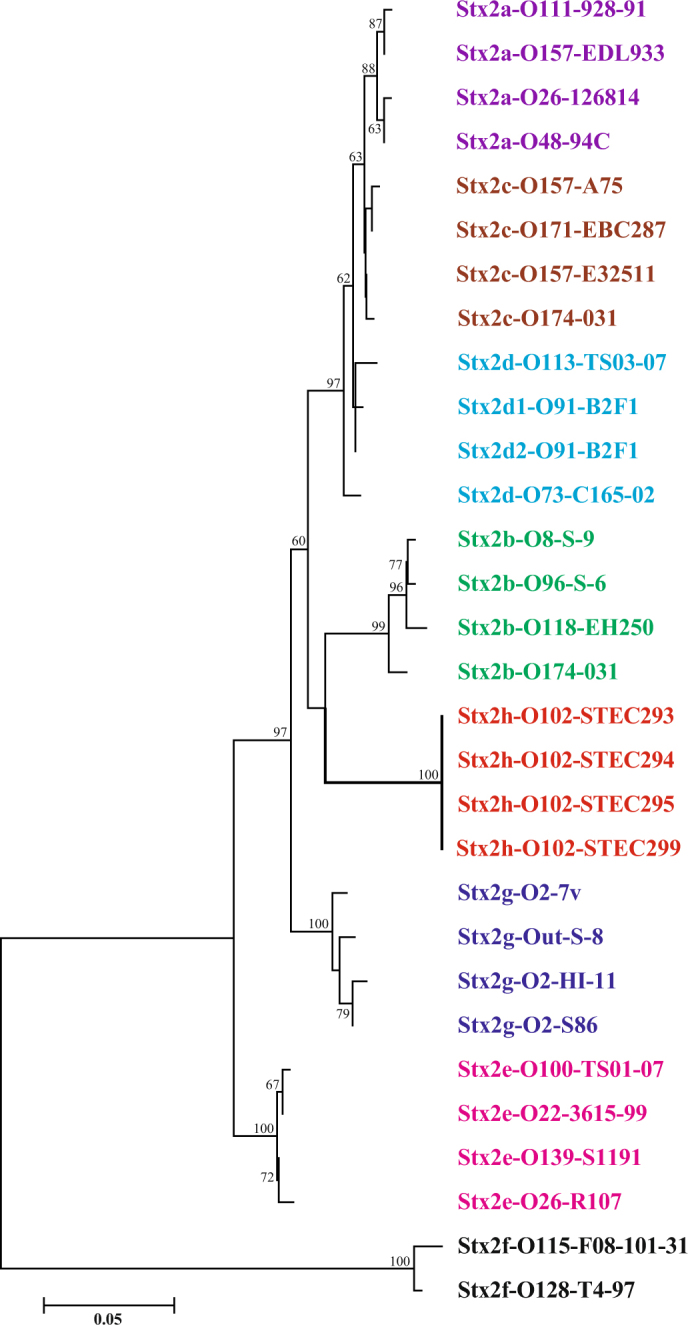

Phylogenetic trees reconstructed using the neighbor-joining algorithm (Fig. 1, see Supplementary Fig. S2 for extended version of this tree), maximum-likelihood and maximum parsimony algorithms shared the same topology and demonstrated that the Stx2 from STEC293, STEC294, STEC295, and STEC299 form a distinct lineage, not clustering with any known Stx2 subtypes and variants. These data suggest these four STEC strains harbor a novel Stx2 subtype. Based on the new nomenclature for Stx, the new Stx subtype was designated Stx2h. STEC299 encoding variant Stx2h-O102-STEC299 was used as type Stx2h strain for further analysis. Comparison of sequences of the stx2h subtype and other existing stx2 subtypes revealed that the nucleic acid sequence of subunit A of the stx2h showed a similarity ranging from 69.7 to 92.9% to the previously reported stx2 subtypes, and 67.2% to 91.3% for subunit B. When comparing sequences of Stx2 holotoxin, the similarity with others ranged from 63.8% to 91.9% in nucleic acid level, and from 71.9% to 92.9% in amino acid level (Table 2). The amino acid alignment for Stx2h-O102-STEC299 holotoxin against other seven subtypes, demonstrated 13 amino acids difference (Fig. 2). The intergenic region between the A and B subunit of stx2h contained 12 nucleotides, exhibiting the same intergenic region size with stx2b, stx2e, stx2f and stx2g, but display distinct nucleotides composition (CAGGAGTTAAAC) with others (Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of Stx2 subtypes by the neighbor-joining method. The neighbor-joining tree was inferred from comparison of combined (A and B) holotoxin amino acid sequences of all Stx2 subtypes. Numbers on the tree indicate bootstrap values calculated for 1000 subsets for branch points >50%. Bar, 0.05 substitutions per site. Stx2 subtypes are indicated by different colors. An extended version of this tree is available as Fig. S2.

Table 2.

Nucleotide/amino acids identities (%) between stx2h and representatives of other seven stx2 subtypes.

| Nucleotide\amino acids | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.stx2a | 92.6 | 99.0 | 97.5 | 94.1 | 72.4 | 97.1 | 92.4 | |

| 2.stx2b | 91.5 | 93.1 | 93.6 | 91.4 | 70.9 | 92.1 | 92.6 | |

| 3.stx2c | 98.4 | 91.8 | 98.0 | 93.6 | 71.6 | 95.1 | 92.4 | |

| 4.stx2d | 96.8 | 93.2 | 97.3 | 94.1 | 72.4 | 95.6 | 92.9 | |

| 5.stx2e | 91.7 | 88.7 | 91.3 | 91.5 | 73.6 | 95.6 | 92.6 | |

| 6.stx2f | 62.3 | 62.7 | 61.8 | 61.8 | 69.3 | 72.9 | 71.9 | |

| 7.stx2g | 93.9 | 91.1 | 92.7 | 93.7 | 91.8 | 64.2 | 92.9 | |

| 8.stx2h | 91.4 | 91.9 | 91.3 | 91.9 | 89.6 | 63.8 | 91.6 |

Figure 2.

Amino acid alignment of Stx2h (A and B) subunits against other Stx2 subtypes. Amino acid conserved with all Stx2 sequences are indicated with an asterisk. Differences between sequences are indicated in black letter.

All four stx2h-isolates gave an expected band about 150-bp by using the stx2h-specific PCR, but seven stx2 subtypes reference strains and a non-O157 STEC collection strains from wild animals in the same sampling region were all negative for stx2h.

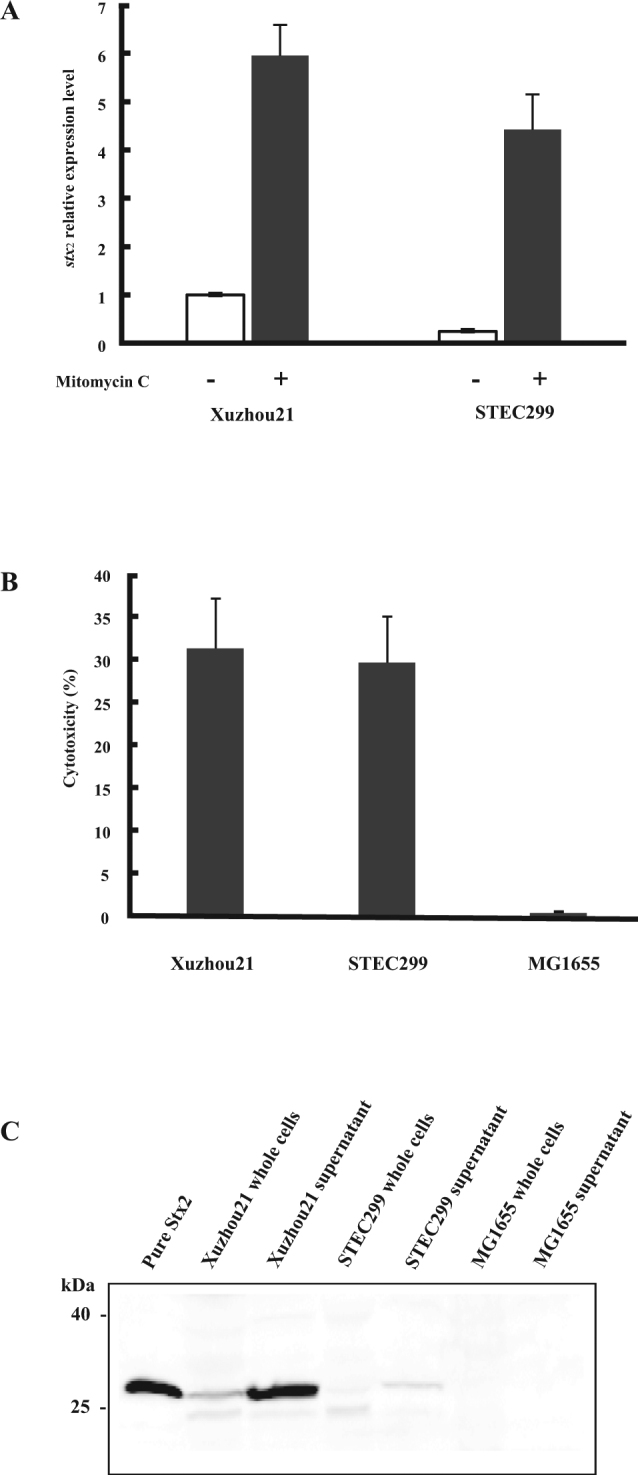

Stx2h is inducible and functional

To determine if Stx2h is inducible, the levels of basal and induced stx2 expression were determined using real-time RT-PCR. Result showed stx2 was expressed constitutively (Fig. 3A), while the basal transcription level in STEC299 was lower (4.2 times) than that observed in the O157:H7 outbreak strain Xuzhou21 under non-inducing conditions. Notably, the induced stx2 expression level is 18.3 times higher than its basal level in STEC299, posting a greater inducing ability than Xuzhou21.The A subunit of novel Stx2h can be recognized against a Stx2 rabbit polyclonal antibody that have been used effectively to recognize all other Stx2 subtypes, while with a lower amount of the protein loaded on the gel (Fig. 3C). Vero cell cytotoxicity assay showed that STEC299 had similar cytotoxicity after 24 hours incubation comparing to the outbreak strain Xuzhou21 (Fig. 3B). These results indicated that stx2h expression was inducible and Stx2h had cytotoxicity to Vero cells.

Figure 3.

Induction of Stx2h production in STEC299. (A) mRNA expression by qRT-PCR. The relative levels of expression under non-induction and induction conditions were relative to the expression level in Xuzhou21 before induction by mitomycin C which was arbitrary set at 1.0. The relative value was averaged from three independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard errors. (B) Vero toxicity assay. The cytotoxicity was detected after 24 h incubation exposure to the induced supernatants overnight. Xuzhou21 was used as positive control; MG1655 was used as negative control. (C) Western blot assays with an anti-Stx2 rabbit polyclonal antibody on whole cells and supernatants from STEC299 induced with mitomycin C with a final concentration of 0.5 μg/ml. Xuzhou21 was used as positive control.

Stability of stx2

To evaluate the stability of stx2h, STEC299 was subcultured daily for two weeks, a sample of overnight growth was detected by a real-time PCR assay for presence of stx2h. The CT value for each sample remained consistent over the two weeks, indicating that stx2h is a relatively stable element within the STEC299 genome.

Genome features of STEC299

The completed genome sequence of STEC299 consists of a circular chromosome of 4,907,118 bp with a G + C content of 50.7% (Fig. S3A), and two plasmids, pSTEC299-1 of 191,691 bp with a C + G content of 45.5% (Fig. S3B) and pSTEC299-2 (59,190 bp) with a C + G content of 43% (Fig. S3C). The whole genome consists of 5,009 coding DNA sequences (CDSs), 22 rRNA, 94 tRNAs, and 12 prophage/prophage-like elements. We searched the two plasmid sequences in GenBank NR database with BLASTN (accessed 24.07.2017), to identify their closest matches, yet both were distinct from all of the currently published existing sequences, with a highest query coverage of 36% for pSTEC299-1 (E. coli strain M18, CP010219.1) and 53% for pSTEC299-2 (E. coli plasmid pRPEC180_47, JN935898.1) only.

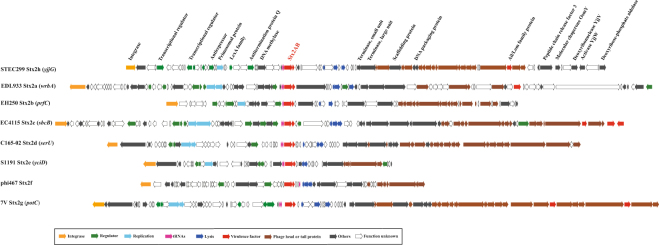

Genetic organization of Stx2h prophage

Shiga toxin-encoding prophages are highly mobile genetic elements that may result in regulation and horizontal transfer of stx genes17,18. We further characterized the Stx2 converting prophages including chromosomal insertion site, genetic sequence, and structure. The novel Stx2h converting prophage is 49,713 bp in size in STEC299, and located adjacent to the yjjG locus, which found to be a novel insertion site ever reported. In total, 93 CDSs were predicted on the Stx2h prophage, among which, Stx phage-specific genes encoding the integrase, transcriptional regulator, antirepressor, antitermination protein Q, and lysis, were found in STEC299 and other Stx2 subtype reference strains, while 37 were hypothetical proteins or mobile elements with unknown function (Fig. 4). Besides the Shiga toxin gene, virulence-related Ail/Lom family outer membrane protein was detected on the Stx2h prophage, which was also present in the Stx2a, Stx2c and Stx2g prophages (Fig. 4). Comparison with the representatives of seven existing Stx2 subtypes prophages (Stx2a-2g) suggests a high diversity among different Stx subtypes-containing phages, in terms of chromosomal insertion sites, structure, and genetic sequences. Different Stx2 subtype prophages contain extensive non-homologous regions, and sequence dissimilarity was also observed for the same functional protein, such as antitermination Q protein.

Figure 4.

Architecture of Stx2h-converting phages and genomic comparison with other Stx2 phages. The figure shows comprehensive analyses of all Stx2 subtypes converting prophages. Corresponding CDSs are colored as indicated. Integration sites of each phage are presented in parentheses.

STEC299 exhibited a hybrid virulence genes spectrum

To determine the pathogenic potential of this newly identified Stx2h harboring strain STEC299, the virulence factors were investigated by using a BLAST search against VFDB (http://www.mgc.ac.cn/). Remarkably, except for stx2, none of STEC main virulence-related factors, like eae, ehxA, saa, efa1was identified in STEC299. Instead, many other virulence factors were identified (Table S2), which mainly belonged to five categories: adherence, invasion, autotransporter, iron uptake, and secretion system. The adherence genes, paa and Dr family of adhesins encoding gene (draC) were found on the large plasmid pSTEC299-1. The type I fimbriae genes (fimA, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, and I), E. coli common pilus (ECP)-related genes (ecpA, B, C, D, E, and ecpR), and F1C fimbriae gene (focC) were identified on chromosome. The invasion gene ibeA, which shared with ExPEC isolates, was detected. In the autotransporter category, enterotoxin gene espC and enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) mucinase gene pic were found on plasmid pSTEC299-2. Tsh (tsh), another autotransporter prevalent in UPEC and APEC isolates was detected on chromosome. In the iron uptake category, iron-regulated genes (fyuA, irp1, irp2, and ybtA, E, P, Q, S, T, U, X), hemin uptake-related genes (chuA, S, T, U, W, X, and Y) and the iron chelator genes (entA, B, C, D, E, F and fepA, B, C, D, E) were identified on chromosome. The type II secretion protein genes (gspD, E, F, G) were found on the plasmid pSTEC299-2. Notably, the majority of virulence genes in STEC299 are miscellaneous ExPEC virulence determinants, including type I fimbriae genes and invasion gene ibeA, which have been regarded as virulence determinants common to ExPEC19,20. Additionally, the presence of fyuA, chuA, and tsh identified in STEC299 has been significantly associated with UPEC and NMEC but not diarrhoeagenic E. coli (DEC)21.

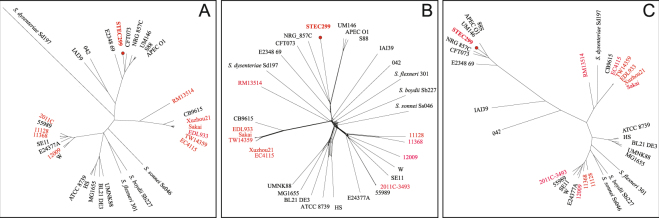

Phylogenetic position of STEC299

The phylogenetic position of STEC299 among a diverse collection of E. coli and Shigella spp. genome sequences comprised of representatives of all major pathotypes was assessed using ribosomal multilocus sequence analysis, whole-genome multilocus sequence typing (wgMLST) and whole-genome phylogenetic analysis. In total 53 ribosomal protein gene sequences were extracted from the annotated whole-genome sequence of the 33 strains. Ribosomal protein L36 and L31 type B gene was excluded from the analysis because of the presence of paralogues in some genomes. A ClonalFrame tree (Fig. 5A) was inferred from the 53 concatenated ribosomal protein gene sequences that are single-copy and shared by the 33 strains, which revealed that the novel Stx2h converting strain STEC299 formed a remote cluster with all 10 reference STEC genomes, while grouped close with strains representing EPEC, UPEC, NMEC, APEC, AIEC. Similarly, neighbor-net phylogeny (Fig. 5B) and Gubbins tree (Fig. 5C) generated with the concatenated sequences of all the 2,321 shared loci found in wgMLST analysis were also consistent with this finding. Our study indicates that the Stx2h-containing strain STEC299 is phylogenetically closer to other pathotypes of E. coli than STEC, thus we propose that STEC299 might evolve from other pathotypes into STEC by acquiring Stx prophage and other virulence factors.

Figure 5.

The phylogenetic relationship of the strain STEC299 with the other 32 reference strains. (A) ClonalFrame tree of the stains inferred from the concatenated ribosomal protein gene sequences that are single-copy and shared (n = 53) by the 33 strains. Three independent and converged runs were merged and a 95% consensus tree was presented in the final graph. (B) Neighbor-net phylogeny generated from wgMLST allele profiles of 2,321 loci that shared by all the strains. The uncertainty and incompatibilities in the dataset were shown as networks. (C) Gubbins tree generated with the concatenated sequences of all the shared loci found in wgMLST analysis. STEC strains are highlighted in red on the three different trees.

Discussion

Shiga toxins (Stx1 and Stx2) are key virulence factors in the pathogenesis of gastroenteritis, HC and HUS, caused by STEC and other Stx-producing bacteria, including Citrobacter freundii, Enterobacter cloacae, Acinetobacter haemolyticus, Aeromonas sp., and Escherichia albertii22–26. A previous study to standardize Stx nomenclature proposed three Stx1 subtypes (Stx1a, Stx1c, and Stx1d) and seven Stx2 subtypes (Stx2a to 2g), based on phylogenetic analysis of Stx holotoxin sequences4. Stx2 was reported to be more often correlated with severe clinical outcomes and development of HUS than Stx127. Further, different Stx2 subtypes are associated with varied clinical symptoms. Strains producing Stx2a, Stx2c, or Stx2d subtype which display close sequences relatedness, are more often correlated with development of HC and HUS27–29, while those producing other (more distantly related) subtypes (Stx2b and Stx2e to Stx2g) are primarily related to a milder course of disease.

Stxs normally reside in bacteriophages, where horizontal gene transfer could lead to emergence of new Stx-subtypes/variants or Stx-producing pathogens18. In a recent study, a novel Stx1 subtype, Stx1e, was identified from an Enterobacter cloacae strain30. The emerging of the new stx subtypes/variants, and new Stx-producing pathotypes pose a great threaten to the public health. Here, we reported a novel Shiga toxin 2 subtype, named Stx2h produced by E. coli O102:H18 strains from marmots in Qinghai–Tibet plateau of China. Stx2h shows high induced level of stx2 expression, and cytotoxicity to Vero cell, and the reactivity with anti-Stx2 antibody, posing diagnostic challenge for the emerging of new Stx subtypes/variants. Remarbly, the novel Stx2h subtype occurred at an unexpectedly high rate of 66.7% (4 of 6) in marmot STEC strains, but was not detected in any of other animal-derived or human STEC strains we investigated in different regions of China so far. The absence of Stx2h in other animal in the same enviroment suggests that it may be a recently emerged subtype that has not yet extensively spread among animals, or it could be limited to a specific host or ecosystem. The occurrence of the new Stx2h subtype from marmots enlarges the pool of Stx2 subtypes and add further information to the global epidemiological picture of STEC strains. Future work should bring into light if the novel Stx2h subtype is specific for STEC strains adapted to marmot or wild animal on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau.

Pathogenic E. coli can be categorized into different pathotypes based on the presence of specific virulence markers. The stx genes specific for STEC reside in the genome of heterogeneous lambdoid prophages, Stx-converting bacteriophages31, which could infect various bacterial hosts wider than expected18. The potential genetic combinations due to gene transfer may result in hybrid pathotype strains. Stx2-phages can infect and lysogenize almost all known pathotypes of E. coli, including both diarrheagenic E. coli (DEC) and extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC)17. The emergence of novel hybrid form of STEC and other E. coli pathotypes might result in more severe disease. For instance, the STEC/enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) hybrid strain O104:H4 caused a large outbreak with numerous HUS cases in Germany in 201132. STEC/enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) hybrid strains have been recovered from various sources and correlated with diarrheal disease and even HUS in humans33,34. A recent report described an STEC/ExPEC hybrid that caused HUS and bacteremia35. STEC/UPEC hybrid strains have also been identified from hospital patients20,36. Our study reveals the presence of virulence factors from multiple pathotypes of E. coli in the Stx2h converting strain STEC299, including type I fimbriae genes, ibeA, chuA, fyuA, and tsh19–21,37. The gene pic, originally identified in the EAEC prototype strain 04238, was present frequently among UPEC strains, with a positive rate of 13% reported by Abe et al.39. The autotransporter gene tsh in E. coli strains are associated with acute pyelonephritis, and are expressed during urinary tract infection40. Considering the severe disease caused by hybrid pathotypes, the pathogenic potential of STEC299 should not be neglected and calls for considerable attention. Further, the combined virulence traits of STEC299 is in accordance with our previous findings that most of the marmot E. coli strains exhibited hybrid forms carrying virulence markers from various pathotypes16, indicating that marmot E. coli strains exhibit a marked genome plasticity. Future work should aid to ascertain if the E. coli strains from marmots show more tendency to represent hybrid genotypes.

Phylogenies inferred from whole genome comparision clearly underlines that STEC299 are phylogenetically closer to other pathotypes of E. coli than STEC group, thus we propose that marmot strain STEC299 may evolved from other pathotypes by horizontal gene transfer and gaining Stx2 phage, which is supported by view that pathogenic E. coli was evolved from non-pathogenic E. coli through horizontal transfer of virulence genes, resulting in mixed pathotypes with enhanced pathogenicity41. However, there are some limitations in genomic analysis, as the number of ExPEC and other pathotypes used for genome comparison is small due to the limited completed reference genomes available, further study are needed to clarify the evolution pattern. Moreover, reference genomes used for comparison are mostly from human-derived strains, there might be a possibility that strains are phylogenetically divergent based on the host origins, thus a various collection of strains are further needed for better understand the phylogenetic placement.

In conclusion, we report the discovery of a novel Shiga toxin 2 subtype from marmot E. coli strains, and enlarges the pool of Stx2 subtypes. Our study shows the new Stx2h converting strain STEC299 is a heteropathogenic strain, which is closer to other pathotypes of E. coli in terms of both phylogenies and virulence gene spectrum. As the emergence of new Stx subtypes and Stx-producing pathotypes has represented a serious problem with the tendency to cause more severe disease, the novel Stx2h should be further included in molecular typing of E. coli strain, and in epidemiological surveillance of E. coli infections.

Methods

Ethics statement

The Marmots (M. himalayana) were sampled as part of the animal plague surveillance program conducted in Yushu Tibetan autonomous prefecture, Qinghai province. The sampling was performed in accordance with the protocol for national plague surveillance program in animals. The study has been reviewed and approved by the ethic committee of National Institute for Communicable Diseases Control and Prevention, China CDC.

Sampling and strain isolation

Of a total of 200 Marmots sampled between July and August 2013, 51 were from Zhongdaxiang (with an altitude of 3599.6 m above sea level (a.s.l)), 120 from Dezhuotan (3025 m a.s.l), and 29 from Dedacun (3625.6 m a.s.l), respectively. The Marmots were captured by cages in the field and sampled in the laboratory of local Centre for Disease Control (CDC). The intestinal contents were collected in 2 ml sterile tubes containing Luria-Bertani (LB) medium in 30% glycerol, which were stored at −20 °C immediately and transported to the laboratory in the National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention in Beijing. Strains were isolated and confirmed to be STEC by the methods we previously described11,13. Briefly, enriched samples in E. coli broth (Land Bridge, Beijing, China) were examined by PCR for the presence of stx genes with primers stx1F/Stx1R and Stx2F/Stx2R respectively13. PCR-positive enrichments were then streaked onto CHROMagarTM ECC agar (CHROMagar, Paris, France), and MacConkey agar (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK). Colonies resembling E. coli were picked and tested for stx genes by single colony duplex PCR assay. Serotyping, detection of main STEC-related virulence factors (stx, eae, ehxA, efa1, saa, paa, toxB, and astA), and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) were conducted as we previously described11,13.

Stx subtyping based on phylogenetic analysis

stx subtypes of STEC isolates were determined by the PCR-based subtyping method4. For strains that failed to be detected by the stx2 subtype-specific primers, the completed stx2 gene was amplified as described previously11,42, then cloned into vector pMD18-T and transformed into E. coli JM109 (Takara, Dalian, China). About 10 transformants were selected for sequencing to discern multiple stx2 subtypes in a PCR product. The 93 representative reference nucleotide sequences of the full stx2 operon of stx2 subtypes and variants (stx2a-stx2g) were downloaded from GenBank as previously described4. The amino acid sequences for the combined A and B holotoxin were translated from the open reading frames. The full nucleotide and amino acid sequences, including A and B subunits, the intergenic regions, were aligned and compared by using Clustal Omega to evaluate the differences between stx2 sequences. Phylogenetic trees based on the holotoxin amino acid sequences were reconstructed with three algorithms, neighbor-joining, maximum likelihood and maximum parsimony, using MEGA 7 software (www.megasoftware.net)43, and the stability of the groupings was estimated by bootstrap analysis (1000 replications). Genetic distances were calculated by the maximum composite likelihood method.

Developing a specific PCR to detect and subtype stx2h

The stx2h and reference nucleotide sequences of stx2a-stx2g were aligned. Subtype-conserved areas were searched to develop a pair of stx2h-specific primers Stx2h-F (5′-AGATCTCATTCTTTATATG-3′) and Stx2h-R (5′-TCCCCATTATATTTAGAG-3′). The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 minutes followed by 30 cycles, each consisting of 30 seconds at 94 °C, 30 seconds at 51 °C and 30 seconds at 72 °C, and a final elongation at 72 °C for 5 minutes using Premix Taq™ ((TaKaRa, Japan). The expected PCR product is 149-bp. Seven stx2 reference strains and a non-STEC collection from yak, marmot, pika, antelope, cattle, goat, pig, food, diarrheal patients and healthy carriers reported previously14 were tested by this subtyping protocol.

Determination of stx2 transcription by real-time reverse-transcription (RT)-PCR

Strains were grown in Luria-Bertani medium at 37 °C with shaking to an OD600 of 0.6., Mitomycin C (BBI, USA) was added to a final concentration of 0.5 μg/ml and incubated for three hours to induce the Stx2 phage. Total RNA was extracted with RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany). Real-time RT-PCR was performed with the Rotor-Gene Q system (Qiagen, Germany) using a One Step SYBRH PrimeScriptTM RT-PCR kit (TaKaRa, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RT-PCR profile was as follows: 42 °C for 10 minutes, 95 °C for 10 seconds, and 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds, 60 °C for 1 minute. Primers stx2F (CAACGGACAGCAGTTATACCACTCT) and stx2R (TTAACGCCAGATATGATGAAACCA) allowed amplification of an stx2 fragment. Primers gapA-F (TATGACTGGTCCGTCTAAAGACAA) and gapA-R (GGTTTTCTGAGTAGCGGTAGTAGC) allowed amplification of an gapA fragment. Expression levels of house-keeping gene gapA (D-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) were used as endogenous control within each sample. The relative level of stx2 expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method44 and the expression in E. coli O157:H7 strain Xuzhou21 under non-inducing condition was arbitrary set at 1.0. The experiment was performed in triplicate for each isolate.

Detection of Stx2 production by Western blot

Western blots were conducted as described45. Briefly, the culture was induced with mitomycin C and incubated overnight. The supernatants and cells were harvested and separated by SDS-PAGE. After PAGE, the proteins were transferred to an Immobilon® PVDF membrane (pore size, 0.45 µm; Merck, Germany). Stx2 rabbit polyclonal antibody was diluted to 1 μg/ml in PBS buffer and incubated for 3 hours at room temperature, and then washed three times in PBST. Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) (IRDye® 800CW) at a 1/20,000 dilution was incubated for 2 h at RT. The blots were washed four more times with PBST, and then visualized with a 5 minutes exposure with a LI-COR Odyssey scanner (LI-COR Biosciences, USA).

Vero cell cytotoxicity

The cell-free supernatants were used for Vero cytotoxicity assay. Briefly, Vero cells were maintained in tissue culture flasks in DMEM (Difco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 24 h. Filtrates were added in triplicate to Vero cells (104 cells per well) in 96-well tissue culture plates, then incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After 24 h, the release of the cytoplasmic lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was detected using the Cytotox96 kit (Promega, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The percentage of cytotoxicity was determined as (experimental release-spontaneous release)/(maximum release-spontaneous release) × 100. The spontaneous release was the amount of LDH activity in the supernatant of uninfected cells, the maximum release was that when cells were lysed with the lysis buffer. E. coli Xuzhou21 and E. coli MG1655 were used as control.

stx2 stability

The stability of stx2 was evaluated as previously described30. Briefly, subcultures of bacteria were prepared for 14 consecutive days. Nucleic acid extracts from the consecutive subcultures were tested using the Rotor-Gene Q system (Qiagen, Germany). The primer Stx2F (GGGCAGTTATTTTGCTGTGGA), Stx2R (GAAAGTATTTGTTGCCGTATTAACGA) and probe Stx2-P FAM-ATGTCTATCAGGCGCGTTTTGACCATCTT-BHQ1were used for stx2detection as described previously46. The reaction mixture consisted of 5 μL of DNA extract, 15 μL of 2 × Premix Ex Tap (Probe qPCR) (TaKaRa, Japan), 1 μL of Stx2-F primer (50 μM), 1 μL of Stx2-R primer (50 μM), 0.5 μL of FAM-labeled probe of stx2(5 μM). Cycling conditions used for real-time PCR amplification were as follows: 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, and 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s and60 °C for 1 min.

DNA isolation and whole-genome sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from an overnight culture using the Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The complete genome was sequenced by single molecule, real-time (SMRT) technology using the Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) sequencing platform47. The data were assembled to generate one circular genome without gaps by using SMRT Analysis 2.3.048. The protein-coding sequences (CDSs), tRNAs and rRNAs were predicted using GeneMarkS49. The prophages were predicated by the PHAge Search Tool (PHAST)50. The virulence factors were predicted through the BLAST tool of NCBI and by using the virulence factor database (VFDB; http://www.mgc.ac.cn/)51.

Stx containing prophage sequence analysis

The sequence of the Stx converting phage was extracted from the complete genome by using the PHASTER (http://phaster.ca/)52, the genome of Stx converting phage was reannotated using the RAST server (http://rast.nmpdr.org/)53, and then manually verified and corrected. Functional annotation of selected CDSs was performed based on the results of homology searches against the public nonredundant protein database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) by using BLASTP. The gene adjacent to the integrase was designated as the phage insertion site54. The full Stx2 phage sequence of the STEC299 was compared in detail to representative Stx2 converting phages and visualized using perl script. The Stx2 phage sequences of the reference strains used in the current study were kindly provided by Dr. David A. Rasko, University of Maryland School of Medicine54.

Phylogenomic Analysis

To generate a robust, high-resolution phylogenomic tree depicting position of the novel Stx2 converting strain STEC299, the genome were compared with 32 E. coli/Shigella spp. completed genomes comprised of representatives of all the major pathotypes (Table S1) by using two strategies: ribosomal protein gene sequence analysis (rMLST)55 and whole-genome multilocus typing (wgMLST). The ribosomal protein subunites (rps) gene sequences were extracted from the annotated whole-genome sequence of the 33 strains. Three independent runs were then carried out with ClonalFrame (version 1.2) on the extracted rps gene sequences and the outputs of the analyses were converged and merged to generate a 95% consensus tree56. For wgMLST analysis, the completed whole-genome sequence of strain EDL933was used as reference to perform an ad hoc wgMLST analysis using Genome Profiler version 2.057. The relationship of the strains was further analyzed with Splits Tree 458. The whole-genome phylogeny was inferred from the concatenated sequences of the loci shared by the 33 whole-genome sequences, which was found in the wgMLST analysis. All the regions with elevated densities of base substitutions were eliminated and phylogenetic relationship were generated by Gubbins59.

Accession numbers

The complete genome sequences of STEC299 are available at GenBank under the accession numbers: STEC299 chromosome (CP022279), plasmid pSTEC299-1 (CP022280), and plasmid pSTEC299-2 (CP022281).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81701977, 81772152), the State Key Laboratory of Infectious Disease Prevention and Control (2015SKLID504), and the National Basic Research Priorities Program of China (2015CB554201). All funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication. J. Z. was funded by the New Zealand Food Safety Science & Research Centre. We are grateful to Dr. David A. Rasko (University of Maryland School of Medicine, USA) for kindly providing the Stx2 phage sequences of the reference strains used in this study. We thank Dr. Flemming Scheutz (WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Escherichia and Klebsiella, Statens Serum Institut, Denmark) for confirmatory analysis and nomenclature of this new Stx2h subtype.

Author Contributions

X.B. and Y.X. designed the project, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. S.F., R.F., Y.Xu, and H.S. carried out the experiments and generated data. J.Z. performed genomic data analysis and edited the paper. X.H. and J.X. provided expertise and feedback and polished the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Xiangning Bai, Shanshan Fu and Ji Zhang contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-25233-x.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Smith JL, Fratamico PM, Gunther NWt. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2014;86:145–197. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800262-9.00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melton-Celsa, A. R. Shiga Toxin (Stx) Classification, Structure, and Function. Microbiol Spectr 2, EHEC-0024-2013, 10.1128/microbiolspec.EHEC-0024-2013 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Strockbine NA, et al. Two toxin-converting phages from Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain 933 encode antigenically distinct toxins with similar biologic activities. Infect Immun. 1986;53:135–140. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.1.135-140.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheutz F, et al. Multicenter evaluation of a sequence-based protocol for subtyping Shiga toxins and standardizing Stx nomenclature. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:2951–2963. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00860-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuller CA, Pellino CA, Flagler MJ, Strasser JE, Weiss AA. Shiga toxin subtypes display dramatic differences in potency. Infect Immun. 2011;79:1329–1337. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01182-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kruger A, Lucchesi PM. Shiga toxins and stx phages: highly diverse entities. Microbiology. 2015;161:451–462. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bibbal D, et al. Prevalence of carriage of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli serotypes O157:H7, O26:H11, O103:H2, O111:H8, and O145:H28 among slaughtered adult cattle in France. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:1397–1405. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03315-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beutin L, Geier D, Zimmermann S, Karch H. Virulence markers of Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains originating from healthy domestic animals of different species. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:631–635. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.631-635.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mora A, et al. Seropathotypes, Phylogroups, Stx subtypes, and intimin types of wildlife-carried, shiga toxin-producing escherichia coli strains with the same characteristics as human-pathogenic isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:2578–2585. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07520-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh P, et al. Characterization of enteropathogenic and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in cattle and deer in a shared agroecosystem. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2015;5:29. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2015.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bai X, et al. Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli in Plateau Pika (Ochotona curzoniae) on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:375. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bai X, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from retail raw meats in China. Int J Food Microbiol. 2015;200:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bai X, et al. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in yaks (Bos grunniens) from the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China. PloS one. 2013;8:e65537. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bai X, et al. Molecular and Phylogenetic Characterization of Non-O157 Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli Strains in China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2016;6:143. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meng Q, et al. Characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from healthy pigs in China. BMC Microbiol. 2014;14:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu S, et al. Insights into the evolution of pathogenicity of Escherichia coli from genomic analysis of intestinal E. coli of Marmota himalayana in Qinghai-Tibet plateau of China. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2016;5:e122. doi: 10.1038/emi.2016.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tozzoli R, et al. Shiga toxin-converting phages and the emergence of new pathogenic Escherichia coli: a world in motion. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014;4:80. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herold S, Karch H, Schmidt H. Shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophages–genomes in motion. Int J Med Microbiol. 2004;294:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Germon P, et al. ibeA, a virulence factor of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 2005;151:1179–1186. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27809-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toval F, et al. Characterization of Escherichia coli isolates from hospital inpatients or outpatients with urinary tract infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:407–418. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02069-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spurbeck RR, et al. Escherichia coli isolates that carry vat, fyuA, chuA, and yfcV efficiently colonize the urinary tract. Infect Immun. 2012;80:4115–4122. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00752-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grotiuz G, Sirok A, Gadea P, Varela G, Schelotto F. Shiga toxin 2-producing Acinetobacter haemolyticus associated with a case of bloody diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3838–3841. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00407-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alperi A, Figueras MJ. Human isolates of Aeromonas possess Shiga toxin genes (stx1 and stx2) highly similar to the most virulent gene variants of Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:1563–1567. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt H, Montag M, Bockemuhl J, Heesemann J, Karch H. Shiga-like toxin II-related cytotoxins in Citrobacter freundii strains from humans and beef samples. Infect Immun. 1993;61:534–543. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.534-543.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paton AW, Paton JC. Enterobacter cloacae producing a Shiga-like toxin II-related cytotoxin associated with a case of hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:463–465. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.463-465.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murakami K, et al. Shiga toxin 2f-producing Escherichia albertii from a symptomatic human. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2014;67:204–208. doi: 10.7883/yoken.67.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orth D, et al. The Shiga toxin genotype rather than the amount of Shiga toxin or the cytotoxicity of Shiga toxin in vitro correlates with the appearance of the hemolytic uremic syndrome. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;59:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawano K, Okada M, Haga T, Maeda K, Goto Y. Relationship between pathogenicity for humans and stx genotype in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli serotype O157. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27:227–232. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0420-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paixao-Cavalcante D, Botto M, Cook HT, Pickering MC. Shiga toxin-2 results in renal tubular injury but not thrombotic microangiopathy in heterozygous factor H-deficient mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;155:339–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Probert WS, McQuaid C, Schrader K. Isolation and identification of an Enterobacter cloacae strain producing a novel subtype of Shiga toxin type 1. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:2346–2351. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00338-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Brien AD, et al. Shiga-like toxin-converting phages from Escherichia coli strains that cause hemorrhagic colitis or infantile diarrhea. Science. 1984;226:694–696. doi: 10.1126/science.6387911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rasko DA, et al. Origins of the E. coli strain causing an outbreak of hemolytic-uremic syndrome in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:709–717. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prager R, Fruth A, Busch U, Tietze E. Comparative analysis of virulence genes, genetic diversity, and phylogeny of Shiga toxin 2g and heat-stable enterotoxin STIa encoding Escherichia coli isolates from humans, animals, and environmental sources. Int J Med Microbiol. 2011;301:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nyholm O, et al. Comparative Genomics and Characterization of Hybrid Shigatoxigenic and Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (STEC/ETEC) Strains. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mariani-Kurkdjian P, et al. Haemolytic-uraemic syndrome with bacteraemia caused by a new hybrid Escherichia coli pathotype. New Microbes New Infect. 2014;2:127–131. doi: 10.1002/nmi2.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bielaszewska M, et al. Heteropathogenic virulence and phylogeny reveal phased pathogenic metamorphosis in Escherichia coli O2:H6. EMBO Mol Med. 2014;6:347–357. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201303133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lara FB, et al. Virulence Markers and Phylogenetic Analysis of Escherichia coli Strains with Hybrid EAEC/UPEC Genotypes Recovered from Sporadic Cases of Extraintestinal Infections. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:146. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harrington SM, et al. The Pic protease of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli promotes intestinal colonization and growth in the presence of mucin. Infect Immun. 2009;77:2465–2473. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01494-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abe CM, et al. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) strains may carry virulence properties of diarrhoeagenic E. coli. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2008;52:397–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heimer SR, Rasko DA, Lockatell CV, Johnson DE, Mobley HL. Autotransporter genes pic and tsh are associated with Escherichia coli strains that cause acute pyelonephritis and are expressed during urinary tract infection. Infect Immun. 2004;72:593–597. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.593-597.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaper JB, Nataro JP, Mobley HL. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:123–140. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gunzer F, et al. Molecular detection of sorbitol-fermenting Escherichia coli O157 in patients with hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1807–1810. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.7.1807-1810.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He X, et al. Development and characterization of monoclonal antibodies against Shiga toxin 2 and their application for toxin detection in milk. J Immunol Methods. 2013;389:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hara-Kudo Y, et al. An interlaboratory study on efficient detection of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O26, O103, O111, O121, O145, and O157 in food using real-time PCR assay and chromogenic agar. Int J Food Microbiol. 2016;230:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCarthy A. Third generation DNA sequencing: pacific biosciences’ single molecule real time technology. Chem Biol. 2010;17:675–676. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berlin K, et al. Assembling large genomes with single-molecule sequencing and locality-sensitive hashing. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:623–630. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Besemer J, Lomsadze A, Borodovsky M. GeneMarkS: a self-training method for prediction of gene starts in microbial genomes. Implications for finding sequence motifs in regulatory regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2607–2618. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.12.2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou Y, Liang Y, Lynch KH, Dennis JJ, Wishart DS. PHAST: a fast phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W347–352. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen L, Zheng D, Liu B, Yang J, Jin Q. VFDB 2016: hierarchical and refined dataset for big data analysis–10 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D694–697. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arndt D, et al. PHASTER: a better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W16–21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aziz RK, et al. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steyert SR, et al. Comparative genomics and stx phage characterization of LEE-negative Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:133. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jolley KA, et al. Ribosomal multilocus sequence typing: universal characterization of bacteria from domain to strain. Microbiology. 2012;158:1005–1015. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.055459-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Didelot X, Falush D. Inference of bacterial microevolution using multilocus sequence data. Genetics. 2007;175:1251–1266. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.063305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang J, Halkilahti J, Hanninen ML, Rossi M. Refinement of whole-genome multilocus sequence typing analysis by addressing gene paralogy. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:1765–1767. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00051-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huson DH. SplitsTree: analyzing and visualizing evolutionary data. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:68–73. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Croucher NJ, et al. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.