Abstract

Insects have a complex chemosensory system that accurately perceives external chemicals and plays a pivotal role in many insect life activities. Thus, the study of the chemosensory mechanism has become an important research topic in entomology. Spodoptera exigua Hübner (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) is a major agricultural polyphagous pest that causes significant agricultural economic losses worldwide. However, except for a few genes that have been discovered, its olfactory and gustatory mechanisms remain uncertain. In the present study, we acquired 144,479 unigenes of S. exigua by assembling 65.81 giga base reads from 6 chemosensory organs (female and male antennae, female and male proboscises, and female and male labial palps), and identified many differentially expressed genes in the gustatory and olfactory organs. Analysis of the transcriptome data obtained 159 putative chemosensory genes, including 24 odorant binding proteins (OBPs; 3 were new), 19 chemosensory proteins (4 were new), 64 odorant receptors (57 were new), 22 ionotropic receptors (16 were new), and 30 new gustatory receptors. Phylogenetic analyses of all genes and SexiGRs expression patterns using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reactions were investigated. Our results found that several of these genes had differential expression features in the olfactory organs compared to the gustatory organs that might play crucial roles in the chemosensory system of S. exigua, and could be utilized as targets for future functional studies to assist in the interpretation of the molecular mechanism of the system. They could also be used for developing novel behavioral disturbance agents to control the population of the moths in the future.

Keywords: Spodoptera exigua, olfactory organ, gustatory organ, transcriptome analysis, chemosensory gene

Introduction

Over the evolutionary process, insects have developed a complex chemosensory system that can accurately perceive external chemicals. The system plays a pivotal role in many insect life activities, such as feeding, mating, host finding, searching for oviposition sites, avoiding predators, and migration (Field et al., 2000; Zhan et al., 2011; Suh et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015a). Numerous studies based on morphological and molecular biology have revealed that the antenna, proboscis, and labial palp are the main olfactory and gustatory organs in this system (Jacquin-Joly and Merlin, 2004; Briscoe et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2017).

The insect chemosensory system involves several different types of genes, including (1) soluble olfactory proteins in the lymph of chemosensilla, e.g., odorant binding proteins (OBPs) (Vogt, 2003; Xu et al., 2009; Zhou, 2010; Pelosi et al., 2018) and chemosensory proteins (CSPs) (Pelosi et al., 2005, 2006; Iovinella et al., 2013) that transfer chemicals via the chemosensilla lymph to corresponding chemosensory receptors, and (2) chemosensory membrane proteins, e.g., olfactory receptors (ORs) (Crasto, 2013; Leal, 2013; Zhang et al., 2015a, 2017), ionotropic receptors (IRs) (Vogt, 2003; Benton et al., 2009; Rytz et al., 2013), and gustatory receptors (GRs) (Clyne et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2011; Briscoe et al., 2013; Ni et al., 2013) that are located on the dendrites of neurons in the chemosensilla and transform chemical signals into electrical signals to stimulate the corresponding behavioral responses of insects (Leal, 2013).

The acquisition, bioinformatics analysis, and expression pattern of putative chemosensory genes are the crucial steps to explore the exact roles of several key genes in the insect chemosensory process. The development of modern molecular biology techniques and experimental equipment, such as high-throughput sequencing, has created more efficient, inexpensive, and higher accuracy technologies than what has been traditionally utilized (McKenna et al., 1994; Picimbon and Gadenne, 2002; Xiu et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2012). These have been successfully applied in the identification of insect chemosensory genes, including many moth species, such as Spodoptera littoralis (Legeai et al., 2011), Sesamia inferens (Zhang et al., 2013), Helicoverpa armigera (Liu et al., 2014b), Plutella xylostella (Yang et al., 2017), and Ectropis grisescens (Li et al., 2017).

The beet armyworm, Spodoptera exigua Hübner (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), is a major agricultural polyphagous pest that causes significant economic losses to many crops worldwide (Xiu and Dong, 2007; Acín et al., 2010; Lai and Su, 2011). To date, only partial chemosensory genes of S. exigua have been identified, including several OBPs (Xiu and Dong, 2007; Zhu et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2015b), CSPs (Liu et al., 2015b) and a few chemosensory receptor genes (Liu et al., 2013, 2014a, 2015b). This is much lower than other moth species from which chemosensory genes have been obtained from transcriptomic data of chemosensory organs. These limited gene resources impede our interpretation of the chemosensory molecular mechanism of S. exigua. To obtain greater olfactory and gustatory gene resources, we utilized the six major olfactory and gustatory organs (female antennae: FA, male antennae: MA, female proboscises: FPr, male proboscises: MPr, female labial palps: FLP, and male labial palps: MLP) of S. exigua adults in the present study. We first built a genetic database of genes that were expressed in the six chemosensory organs of S. exigua using an Illumina HiSeq™ 4000 sequencing platform and completely identified 159 genes (110 genes were newly obtained) as being potentially involved in the chemosensory system. To postulate the functions of these identified genes, we performed phylogenetic analyses of all genes and investigated SexiGRs expression patterns using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). Our results showed that several of the genes had differential expression in olfactory organs compared to gustatory organs that might play different and crucial roles in the chemosensory system of S. exigua, and could be utilized as targets for future functional studies (using the heterologous expression system of Xenopus oocytes or Escherichia coli in vitro and with genetic modification by the CRISPR/Cas9 editing system in vivo) to assist in the interpretation of the molecular mechanism of the system.

Materials and methods

Insects rearing and tissue collection

S. exigua larvae were purchased from Keyun Biology Company in Henan province, China. As we previous studies (Zhang et al., 2017a), we used same rearing conditions and methods to rear the insect. For transcriptome sequencing, 200 female antennae (FA), 200 male antennae (MA), 300 female proboscises (FPr), 300 male proboscises (MPr), 300 female labial palps (FLP), 300 male labial palps (MLP), 30 female abdomen (FAb), and 30 male abdomen (MAb) were collected from 3-day-old unmated adults. For the tissue distribution analysis, 100 FA, 100 MA, 200 FLP, 200 MLP, 200 FP, and 200 MP for each replicate experiment were collected under the same conditions. All these organs were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use.

cDNA library preparation, clustering, and sequencing

Sample total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). cDNA library preparation and Illumina sequencing were carried out by Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The 1.5 μg total RNA per sample was used as input material for the RNA sample preparations, and sequencing libraries were generated using NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (NEB, USA) following manufacturer's recommendations and index codes were added to attribute sequences to each sample. Briefly, mRNA was purified from total RNA using poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads. Fragmentation was carried out using divalent cations under elevated temperature in NEBNext First Strand Synthesis Reaction Buffer (5X). First strand cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primer and M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (RNase H-) (NEB, USA). Second strand cDNA synthesis was subsequently performed using DNA Polymerase I (NEB, USA) and RNase H (NEB, USA). Remaining overhangs were converted into blunt ends via exonuclease/polymerase activities. After adenylation of 3′ ends of DNA fragments, NEBNext Adaptor with hairpin loop structure were ligated to prepare for hybridization. In order to select cDNA fragments of preferentially 150~200 bp in length, the library fragments were purified with AMPure XP system (Beckman Coulter, Beverly, USA). Then 3 μL USER Enzyme (NEB, USA) was used with size-selected, adaptor-ligated cDNA at 37°C for 15 min followed by 5 min at 95°C before PCR. Then PCR was performed with Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase, Universal PCR primers, and Index (X) Primer. At last, PCR products were purified (AMPure XP system) and library quality was assessed on the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system.

The clustering of the index-coded samples was performed on a cBot Cluster Generation System using TruSeq PE Cluster Kit v3-cBot-HS (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After cluster generation, the library preparations were sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq™ 4000 platform and paired-end reads were generated.

Transcriptome assembly and gene functional annotation

Transcriptome assembly was accomplished based on the reads using Trinity (r20140413p1) (Li et al., 2010; Grabherr et al., 2011) with min_kmer_cov set to 2 by default and all other parameters set default. The assembly sequences of Trinity were deemed to be unigenes. Unigene function was annotated based on the following databases: Nr (NCBI non-redundant protein sequences) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/ and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/), Pfam (Protein family) (https://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/), KOG/COG (Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG/), Swiss-Prot (A manually annotated and reviewed protein sequence database) (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/uniprot/), KO (KEGG Ortholog database) (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) and GO (Gene Ontology) (http://www.geneontology.org/).

Differential expression analysis

Firstly, the read counts were adjusted by edgeR 3.0.8 program package through one scaling normalized factor for each sequenced library. Then, the differential expression analysis of two samples was performed using the DEGseq 1.12.0 R package (Wang et al., 2010). P-value was adjusted using q-value (Storey, 2003). q < 0.005 & |log2(foldchange)|>1 was set as the threshold for significantly differential expression.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted using the MiniBEST Universal RNA Extraction Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), following the manufacturer's instructions, in which we used DNase I to digest sample DNase to avoid genomic DNA contamination. The RNA quality was assessed spectrophotometrically (Biofuture MD2000D, UK). Single-stranded cDNA templates were synthesized from 1 μg total RNA obtained from various tissue samples using the PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturers' instructions.

Sequence and phylogenetic analysis

The ORFs of the chemosensory genes were predicted by using ORF Finder (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html), and the similarity searches of genes were performed by using the NCBI-BLAST Server (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Putative N-terminal signal peptides (SP) of SexiOBPs and SexiCSPs were predicted by SignalP 4.1 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) (Petersen et al., 2011). Transmembrane domains (TMD) of SexiORs, SexiGRs, and SexiIRs were predicted by TMHMM Server Version 2.0 (Krogh et al., 2001) (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM).

Phylogenetic trees were constructed for the analysis of five family chemosensory genes of S. exigua, based on gene sequences of S. exigua and those of other insects. The OBP data set contained 24 sequences from S. exigua (Table S1), and 90 from other species, including B. mori (Gong et al., 2009), M. sexta (Grosse-Wilde et al., 2011), and A. lepigone (Zhang et al., 2017b). The CSP data set contained 19 sequences from S. exigua (Table S1), and 55 from other species, including B. mori (Gong et al., 2007), M. sexta (Grosse-Wilde et al., 2011), and A. lepigone (Zhang et al., 2017b). The OR data set contained 64 sequences from S. exigua (Table S1), and 91 from other species (Tanaka et al., 2009; Zhan et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2015b). The IR data set contained 22 sequences from S. exigua (Table S1), and 131 from other species (Croset et al., 2010; Olivier et al., 2011; Rimal and Lee, 2018). The GR data set contained 30 sequences from S. exigua (Table S1), and 126 from other species (Zhan et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2014b; Guo et al., 2017). Then, we used ClustalX 1.83 (Larkin et al., 2007) to align amino acid sequences from the same family gene, and used PhyML 3.1 (Guindon et al., 2010) based on the LG substitution model (Le and Gascuel, 2008) with Nearest Neighbor Interchange (NNI) to construct the phylogenetic trees, and the branch support of tree estimated by a Bayesian-like transformation of the aLRT (aBayes) method (Anisimova et al., 2011). Lastly, we created and edited the different trees by using the FigTree 1.4.2 software (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis

According to the minimum information for publication of qPCR experiments (Bustin et al., 2009) and our previous studies (Zhang et al., 2017a), we performed the qPCR assay of tissue distribution of SexiGRs in ABI 7300 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) by using 2×SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (YIFEIXUE BIO TECH, Nanjing, China) as the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the reaction programs were 10 min at 95°C, 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. The qPCR primers (Table S2) were designed using Beacon Designer 7.9 (PREMIER Biosoft International, CA, USA). Then, the relative expression levels of SexiGRs mRNA were calculated based on the Ct-values of target gene and two reference genes SexiGAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) and SexiEF (elongation factor-1 alpha) by using the Q-Gene method in Microsoft Excel-based software of Visual Basic (Muller et al., 2002; Simon, 2003), the qPCR data are listed in Table S3. To ensure the reliability of the results, we carried out three biological replications for each sample and three technical replications for each biological replication.

Statistical analysis

Data (mean ± SE) from various samples were subjected to one-way nested analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the least significant difference test (LSD) for comparison of means using SPSS Statistics 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results and discussion

Overview of transcriptomes from the six organs

We used next-generation sequencing to sequence the six cDNA libraries constructed from the chemosensory organs (FA, MA, FPr, MPr, FLP, and MLP) of S. exigua adults based on the Illumina HiSeq™ 4000 platform and acquired 65.81 (from 10.60 to 11.90) giga base reads. After clustering and redundancy filtering, we finally obtained 144,479 unigenes and 266,645 transcripts with a N50 length of 2,177 base pair (bp) and 1,552 bp, respectively (Table 1). Statistics showed that 59.22% of the 144,479 unigenes were greater than 500 bp in length (Figure 1). The number of reads, unigenes, and transcripts were higher than most other insects based on transcriptome studies.

Table 1.

Summary of S. exigua transcriptome assembly.

| Sample name | FA | MA | FPr | MPr | FLP | MLP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total size (Gb) | 10.61 | 11.27 | 11.90 | 10.69 | 10.74 | 10.60 |

| GC percentage (%) | 43.58 | 42.93 | 45.13 | 45.00 | 46.80 | 46.35 |

| Q20 percentage (%) | 95.95 | 96.01 | 96.53 | 96.90 | 94.92 | 96.49 |

| Number of transcripts | 266,645 | |||||

| Total unigene | 144,479 | |||||

| Total transcript nucleotides | 202,244,136 | |||||

| Total unigene nucleotides | 168,211,374 | |||||

| N50 of transcripts (nt) | 1,552 | |||||

| N50 of unigenes (nt) | 2,177 | |||||

| Max length of unigenes (nt) | 30,184 | |||||

| Min length of unigenes (nt) | 201 | |||||

| Median length of unigenes (nt) | 584 | |||||

| Unigenes with homolog in NR | 60,373 | |||||

Figure 1.

Distribution of unigene size in the S. exigua transcriptome assembly.

In total, 60,373 unigenes were matched to entries in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) non-redundant (NR) protein database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein) by a BLASTX homology search with a cut-off e-value of 10−5. The highest match percentage (37.40%) was identified with sequences of Bombyx mori followed by sequences of Danaus plexippus (15.60%), P. xylostella (13.20%), Homo sapiens (4.30%), and H. armigera (1.40%; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of homologous hits of the S. exigua unigenes to other insect species. The S. exigua transcripts were searched by Blastx against the Nr protein database with a cutoff E-value 10−5. Species that have more than 1% matching hits to the S. exigua transcripts are shown.

Based on methodology described in our previous studies (Zhang et al., 2013; Li et al., 2015), we applied Blast2GO to classify the functional groups of all unigenes. The results showed that only 29.29% (42,331) of the 144,479 unigenes could be annotated based on the sequence homology, with this proportion similar to that found in other insects (Gu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; He et al., 2017). One possible reason for this might be that a great amount of S. exigua unigenes belong to non-coding or homologous genes without a gene ontology (GO) term. In addition, the GO annotation of S. exigua unigenes displayed similar classification to the unigenes of chemosensory organs from other moth species (Grosse-Wilde et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2013; Cao et al., 2014; Xia et al., 2015). For example, unigenes of S. exigua during biological processes were predicted to be mostly enriched in three sub-categories: cellular, metabolic, and single-organism processes. There was also expected to be similarity in the cellular components (e.g., cell, cell part, and organelle) and molecular function categories (binding, catalytic, and transporter activity; Figure 3), indicating that some unigenes in these sub-categories might play important roles in the chemosensory behavior of moths.

Figure 3.

Gene ontology (GO) classification of the S. exigua unigenes with Blast2GO program.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

To investigate the DEGs among different organs, we compared each organ pair-wise within each sex against all other organs (Figure 4). Gene expression dynamics can be reflected by up- or down-regulation among the six different organs by pairwise comparisons. The results showed that there were a number of DEGs between different organs and different sexes, and the number of DEGs was highest in FPr vs. FLP (6,029 genes in total: 4,050 up-regulated genes and 1,979 down-regulated genes), followed by MA vs. FPr (5,127 genes in total: 1,928 up-regulated genes and 3,199 down-regulated genes), and MPr vs. FLP (4,033 genes in total: 2,513 up-regulated genes and 1,520 down-regulated genes). This indicates that these DEGs, especially in the gustatory vs. olfactory organs, provide substantial genetic sources that are important for studying the differential mechanism of gustatory vs. olfactory organs in S. exigua. Additionally, they provide some important target genes to analyse the functions of expressed sex-specific genes to reveal sex differences in chemosensory mechanisms in the future.

Figure 4.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) among the different organs of S. exigua. FA, female antennae; MA, male antennae; FLP, female labial palps; MLP, male labial palps; FPr, female proboscises; MPr, male proboscises.

Identification of putative chemosensory genes

Based on sequence similarity analyses and characteristics of insect chemosensory genes from previous studies (Xu et al., 2009; Croset et al., 2010; Zhou, 2010; Zhang et al., 2011; Ray et al., 2014), such as the conserved C-pattern of OBPs and CSPs, and the conserved transmembrane structure and motifs of chemosensory receptors (ORs, IRs, and GRs), we totally identified 159 putative genes from the transcriptomic data of S. exigua chemosensory organs that belonged to five insect chemosensory gene families. These included 24 OBPs, 19 CSPs, 64 ORs, 22 IRs, and 30 GRs (Tables 2, 3). The number of putative chemosensory genes of S. exigua identified in the present study was higher than that in other moth species where the same family genes had been identified by analysis of the transcriptome of specific organs. This included H. armigera (143 genes: 34 OBPs, 18 CSPs, 60 ORs, 21 IRs, and 10 GRs) (Liu et al., 2014b), H. assulta (147 genes: 29 OBPs, 17 CSPs, 64 ORs, 19 IRs, and 18 GRs) (Xu et al., 2015), and P. xyllostella (116 genes: 24 OBPs, 15 CSPs, 54 ORs, 16 IRs, and 7 GRs) (Yang et al., 2017). We found that the amount of transcriptomic data of these three different moth species was less than that of S. exigua in the present study, which suggests that the large amount of transcriptomic data could help us obtain more insect chemosensory genes.

Table 2.

The Blastx match of S. exigua putative OBP and CSP genes.

| Gene | ORF | Signal | Complete | Best Blastx Match | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | (aa) | Peptide | ORF | Name | Acc. No. | Species | E-value | Identity (%) |

| ODORANT BINDING PROTEIN (OBP) | ||||||||

| PBP1 | 164 | 1–23 | Y | Pheromone binding protein 1 | AAS46620.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 1.00E-66 | 100 |

| PBP2 | 170 | 1–27 | Y | Pheromone binding protein 2 | AAS55551.2 | Spodoptera exigua | 5.00E-82 | 100 |

| PBP3 | 164 | 1–22 | Y | Pheromone binding protein 3 | ACY78413.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 2.00E-110 | 100 |

| GOBP1 | 164 | 1–19 | Y | General binding protein 1 | ACY78412.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 2.00E-84 | 100 |

| GOBP2 | 162 | 1–17 | Y | Odorant binding protein 2 | AGH70098.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 5.00E-28 | 100 |

| OBP1 | 147 | 1–21 | Y | Odorant binding protein 1 | ADY17883.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 1.00E-29 | 100 |

| OBP2 | 133 | 1–17 | Y | Odorant binding protein 2 | ADY17884.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 4.00E-69 | 100 |

| OBP4 | 145 | 1–17 | Y | Odorant binding protein 4 | ADY17886.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 1.00E-96 | 100 |

| OBP5 | 121 | N | Y | Odorant binding protein 5 | AFM77983.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 4.00E-75 | 100 |

| OBP7 | 157 | 1–20 | Y | Odorant binding protein 7 | ADY17882.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 2.00E-105 | 100 |

| OBP7 | 142 | 1–21 | Y | Odorant binding protein 7 | AGH70103.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 2.00E-92 | 100 |

| OBP8 | 149 | 1–26 | Y | Odorant binding protein 8 | AGH70104.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 3.00E-25 | 100 |

| OBP9 | 133 | 1–16 | Y | Odorant binding protein 9 | AGH70105.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 8.00E-48 | 100 |

| OBP11 | 173 | N | Y | Odorant binding protein 11 | AGH70107.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 2.00E-88 | 100 |

| OBP12 | 145 | 1–24 | Y | SexiOBP12 | AGP03458.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 8.00E-71 | 100 |

| OBP17 | 148 | 1–17 | Y | Odorant binding protein 17 | AKT26495.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 1.00E-79 | 100 |

| OBP18 | 186 | 1–17 | Y | Odorant binding protein 18 | AKT26496.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 2.00E-52 | 100 |

| OBP24 | 184 | 1–20 | Y | Odorant binding protein 24 | AKT26501.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 6.00E-45 | 100 |

| OBP25 | 239 | 1–19 | Y | Odorant binding protein 25 | AKT26502.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 2.00E-166 | 100 |

| OBP27 | 118 | N | Y | Odorant binding protein 27 | AKT26504.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 9.00E-57 | 100 |

| ABP | 147 | 1–21 | Y | Antennal binding protein | ADY17881.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 2.00E-59 | 100 |

| OBP-N1 | 137 | 1–19 | Y | General odorant-binding protein 69a-like | XP_022827633.1 | Spodoptera litura | 1.00E-68 | 97 |

| OBP-N2 | 110 | N | N | Odorant binding protein OBP6 | ALJ30193.1 | Spodoptera litura | 7.00E-17 | 37 |

| OBP-N3 | 127 | 1–21 | Y | Odorant binding protein 6 | AKI87967.1 | Spodoptera litura | 1.00E-71 | 99 |

| CHEMOSENSORY PROTEIN (CSP) | ||||||||

| CSP1 | 128 | 1–18 | Y | Chemosensory protein 1 | ABM67688.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 8.00E-82 | 100 |

| CSP2 | 128 | 1–18 | Y | Chemosensory protein CSP2 | ABM67689.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 9.00E-72 | 100 |

| CSP3 | 126 | 1–16 | Y | Chemosensory protein CSP3 | ABM67690.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 7.00E-77 | 100 |

| CSP4 | 123 | 1–18 | Y | Chemosensory protein CSP4 | AKT26481.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 2.00E-80 | 100 |

| CSP5 | 131 | 1–25 | Y | Chemosensory protein 5 | AKT26482.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 2.00E-69 | 98 |

| CSP6 | 127 | 1–17 | Y | Chemosensory protein 6 | AKT26483.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 3.00E-69 | 100 |

| CSP7 | 128 | 1–16 | Y | Chemosensory protein 7 | AKT26484.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 4.00E-20 | 100 |

| CSP8 | 107 | 1–17 | Y | Chemosensory protein 8 | AKT26485.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 9.00E-52 | 100 |

| CSP10 | 122 | 1–19 | Y | Chemosensory protein 10 | AKT26486.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 7.00E-72 | 100 |

| CSP11 | 122 | 1–16 | Y | Chemosensory protein 11 | AKT26487.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 2.00E-30 | 100 |

| CSP12 | 125 | 1–15 | Y | Chemosensory protein 12 | AKT26488.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 1.00E-62 | 100 |

| CSP13 | 123 | 1–16 | Y | Chemosensory protein CSP13 | AKT26489.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 2.00E-74 | 100 |

| CSP14 | 287 | 1–16 | Y | Chemosensory protein 14 | AKT26490.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 1.00E-40 | 100 |

| CSP19 | 122 | 1–17 | Y | Chemosensory protein 19 | AKT26493.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 7.00E-71 | 100 |

| CSP20 | 107 | 1–18 | Y | Chemosensory protein 20 | AKT26494.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 3.00E-54 | 100 |

| CSP-N1 | 148 | 1–21 | Y | Chemosensory protein 4 | AND82446.1 | Athetis dissimilis | 5.70E-71 | 77 |

| CSP-N2 | 123 | 1–18 | Y | Putative chemosensory protein CSP3 | ALJ30214.1 | Spodoptera litura | 7.00E-79 | 99 |

| CSP-N3 | 98 | N | N | Chemosensory protein CSP | AAY26143.1 | Spodoptera litura | 1.00E-65 | 100 |

| CSP-N4 | 123 | 1–16 | Y | Putative chemosensory protein CSP6 | ALJ30217.1 | Spodoptera litura | 8.00E-75 | 99 |

Table 3.

The Blastx Match of S. exigua putative OR, IR and GR genes.

| Gene | ORF | TMD | Complete | Best Blastx Match | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | (aa) | ORF | Name | Acc. No. | Species | E-value | Identity (%) | |

| ODORANT RECEPTOR (OR) | ||||||||

| Orco | 473 | 7 | Y | Putative chemosensory receptor 2 | AAW52583.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 0.00E+00 | 100 |

| OR1 | 290 | – | N | Putative odorant receptor OR61 | AOE48066.1 | Athetis lepigone | 0.00E+00 | 79 |

| OR2 | 415 | 6 | Y | Putative odorant receptor OR25 | AOE48030.1 | Athetis lepigone | 0.00E+00 | 70 |

| OR3 | 413 | 7 | Y | Odorant receptor | AEF32141.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 0.00E+00 | 99 |

| OR4 | 130 | – | N | Putative olfactory receptor 51 | AGG08876.1 | Spodoptera litura | 7.00E−86 | 72 |

| OR5 | 114 | – | N | Odorant receptor | AIG51858.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 6.00E−60 | 83 |

| OR6 | 432 | 5 | Y | Odorant receptor 6 | AGH58119.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 0.00E+00 | 99 |

| OR7 | 442 | 6 | Y | Olfactory receptor 2 | JAV45863.1 | Mythimna separata | 0.00E+00 | 86 |

| OR8 | 60 | – | N | Olfactory receptor 24 | AQQ73504.1 | Heliconius melpomene rosina | 1.00E−09 | 58 |

| OR9 | 312 | – | N | Putative chemosensory receptor 9 | CAD31950.1 | Heliothis virescens | 7.00E−122 | 64 |

| OR10 | 402 | 6 | Y | Odorant receptor | AIG51887.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 0.00E+00 | 87 |

| OR11 | 435 | 7 | Y | Odorant receptor 11 | AGH58120.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 0.00E+00 | 100 |

| OR12 | 418 | 6 | Y | Odorant receptor 50 | KOB74670.1 | Operophtera brumata | 4.00E−144 | 51 |

| OR13 | 445 | 5 | Y | Odorant receptor 13 | AGH58121.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 0.00E+00 | 99 |

| OR14 | 393 | 6 | Y | Odorant receptor | AIG51868.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 0.00E+00 | 80 |

| OR15 | 247 | – | N | Putative odorant receptor OR44 | AOE48049.1 | Athetis lepigone | 1.00E−156 | 90 |

| OR16 | 432 | 4 | Y | Odorant receptor 16 | AGH58122.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 0.00E+00 | 99 |

| OR17 | 207 | – | N | Odorant receptor | AIG51882.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 7.00E−142 | 76 |

| OR18 | 94 | – | N | Putative odorant receptor OR56 | AOE48061.1 | Athetis lepigone | 4.00E−22 | 68 |

| OR19 | 303 | – | N | Odorant receptor 15 | ALM26204.1 | Athetis dissimilis | 1.00E−163 | 70 |

| OR20 | 399 | 5 | Y | Putative odorant receptor OR27 | AOE48032.1 | Athetis lepigone | 0.00E+00 | 81 |

| OR21 | 418 | 5 | Y | Odorant receptor 38 | ALM26228.1 | Athetis dissimilis | 0.00E+00 | 87 |

| OR22 | 320 | – | N | Olfactory receptor 11 | JAV45854.1 | Mythimna separata | 0.00E+00 | 86 |

| OR23 | 414 | 6 | Y | Odorant receptor 50 | KOB74670.1 | Operophtera brumata | 0.00E+00 | 64 |

| OR24 | 381 | 6 | Y | Odorant receptor | AIG51892.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 0.00E+00 | 81 |

| OR25 | 235 | – | N | Odorant receptor | AIG51900.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 1.00E−126 | 85 |

| OR26 | 289 | – | N | Putative odorant receptor OR12 | AOE48017.1 | Athetis lepigone | 2.00E−121 | 75 |

| OR27 | 236 | – | N | Olfactory receptor 17 | AGK90007.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 2.00E−111 | 74 |

| OR28 | 134 | – | N | Putative odorant receptor SinfOR18 | AIF79425.1 | Sesamia inferens | 3.00E−71 | 85 |

| OR29 | 373 | 5 | Y | Odorant receptor | AIG51879.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 0.00E+00 | 83 |

| OR30 | 351 | 5 | Y | Putative odorant receptor OR23 | AOE48028.1 | Athetis lepigone | 0.00E+00 | 75 |

| OR31 | 263 | – | N | Putative olfactory receptor 12 | AGG08878.1 | Spodoptera litura | 0.00E+00 | 97 |

| OR32 | 156 | – | N | Odorant receptor | AIG51886.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 2.00E−80 | 77 |

| OR33 | 240 | – | N | Odorant receptor 37 | ALM26227.1 | Athetis dissimilis | 2.00E−161 | 59 |

| OR34 | 146 | – | N | Olfactory receptor 41 | JAV45824.1 | Mythimna separata | 8.00E−81 | 83 |

| OR35 | 366 | 6 | Y | Putative olfactory receptor 19 | AGG08879.1 | Spodoptera litura | 0.00E+00 | 90 |

| OR36 | 422 | 5 | Y | Putative olfactory receptor 44 | AGG08877.1 | Spodoptera litura | 0.00E+00 | 97 |

| OR37 | 241 | – | N | Putative odorant receptor OR20 | AOE48025.1 | Athetis lepigone | 7.00E−128 | 70 |

| OR38 | 157 | – | N | Olfactory receptor 15 | JAV45850.1 | Mythimna separata | 3.00E−91 | 94 |

| OR39 | 335 | – | N | Odorant receptor 17 | ALM26206.1 | Athetis dissimilis | 1.00E−173 | 74 |

| OR40 | 463 | 5 | Y | Odorant receptor 4-like | XP_011559211.1 | Plutella xylostella | 0.00E+00 | 75 |

| OR41 | 95 | – | N | Putative chemosensory receptor 10 | CAG38111.1 | Heliothis virescens | 2.00E−94 | 97 |

| OR42 | 109 | – | N | Olfactory receptor 10 | JAV45855.1 | Mythimna separata | 5.00E−41 | 62 |

| OR43 | 258 | – | N | Odorant receptor 62 | ALM26245.1 | Athetis dissimilis | 0.00E+00 | 85 |

| OR44 | 416 | 6 | Y | Odorant receptor | AIG51890.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 0.00E+00 | 74 |

| OR45 | 161 | – | N | Odorant receptor 85 | ALM26250.1 | Athetis dissimilis | 2.00E−85 | 77 |

| OR46 | 390 | 6 | Y | Odorant receptor | AIG51903.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 6.00E−169 | 61 |

| OR47 | 321 | – | N | Putative chemosensory receptor 3 | CAD31852.1 | Heliothis virescens | 3.00E−165 | 79 |

| OR48 | 407 | 6 | Y | Odorant receptor | AIG51860.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 0.00E+00 | 69 |

| OR49 | 309 | – | N | Putative odorant receptor OR9 | AOE48014.1 | Athetis lepigone | 2.00E−126 | 55 |

| OR50 | 124 | – | N | Olfactory receptor 7 | JAV45858.1 | Mythimna separata | 2.00E−72 | 79 |

| OR51 | 194 | – | N | Putative odorant receptor OR36 | AOE48041.1 | Athetis lepigone | 2.00E−107 | 78 |

| OR52 | 392 | 5 | Y | Putative odorant receptor OR53 | AOE48058.1 | Athetis lepigone | 0.00E+00 | 80 |

| OR53 | 396 | 6 | Y | Odorant receptor | AIG51856.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 2.00E−174 | 60 |

| OR54 | 89 | – | N | Odorant receptor 41 | ALM26231.1 | Athetis dissimilis | 3.00E−119 | 85 |

| OR55 | 380 | 4 | Y | Putative odorant receptor OR55 | AOE48060.1 | Athetis dissimilis | 0.00E+00 | 66 |

| OR56 | 70 | – | N | Olfactory receptor | KOB68320.1 | Operophtera brumata | 2.00E−21 | 59 |

| OR57 | 396 | 5 | Y | Odorant receptor 47 | ALM26237.1 | Athetis dissimilis | 6.00E−162 | 58 |

| OR58 | 393 | 5 | Y | Olfactory receptor 37 | JAV45828.1 | Mythimna separata | 0.00E+00 | 83 |

| OR59 | 341 | – | N | Odorant receptor 6 | AGH58119.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 0.00E+00 | 77 |

| OR60 | 133 | – | N | Odorant receptor | AIG51873.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 3.00E−156 | 74 |

| OR61 | 408 | 4 | Y | Odorant receptor | AIG51891.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 0.00E+00 | 81 |

| OR62 | 398 | 3 | Y | Odorant receptor | AFC36918.1 | Spodoptera exigua | 0.00E+00 | 99 |

| OR63 | 257 | – | N | Putative odorant receptor OR60 | AOE48065.1 | Athetis lepigone | 2.00E−87 | 77 |

| IONOTROPIC RECEPTOR (IR) | ||||||||

| IR1 | 329 | – | N | Putative chemosensory ionotropic receptor IR68a | ADR64682.1 | Spodoptera littoralis | 0.00E+00 | 93 |

| IR2 | 542 | 3 | Y | Putative chemosensory ionotropic receptor IR76b | ADR64687.1 | Spodoptera littoralis | 0.00E+00 | 94 |

| IR3 | 722 | – | N | Ionotropic receptor 8a | BAR64796.1 | Ostrinia furnacalis | 0.00E+00 | 79 |

| IR4 | 874 | 3 | Y | Ionotropic receptor 93a | BAR64811.1 | Ostrinia furnacalis | 0.00E+00 | 78 |

| IR5 | 653 | 3 | Y | Putative ionotropic receptor IR1.2 | AOE48004.1 | Athetis lepigone | 0.00E+00 | 69 |

| IR6 | 539 | – | N | Putative chemosensory ionotropic receptor IR1 | ADR64688.1 | Spodoptera littoralis | 0.00E+00 | 77 |

| IR7 | 269 | – | N | Putative chemosensory ionotropic receptor IR87a | ADR64689.1 | Spodoptera littoralis | 0.00E+00 | 97 |

| IR8 | 595 | 3 | Y | Ionotropic receptor 7d.3 | AJD81625.1 | Helicoverpa assulta | 0.00E+00 | 80 |

| IR9 | 606 | 3 | Y | Putative chemosensory ionotropic receptor IR41a | ADR64681.1 | Spodoptera littoralis | 0.00E+00 | 91 |

| IR10 | 851 | – | N | Putative chemosensory ionotropic receptor IR21a | ADR64678.1 | Spodoptera littoralis | 0.00E+00 | 92 |

| IR11 | 630 | 4 | Y | Putative chemosensory ionotropic receptor IR75q.2 | ADR64685.1 | Spodoptera littoralis | 0.00E+00 | 92 |

| IR12 | 206 | – | N | Ionotropic receptor 60a | AIG51919.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 4.00E−94 | 71 |

| IR13 | 459 | – | N | Putative chemosensory ionotropic receptor IR75p | ADR64684.1 | Spodoptera littoralis | 0.00E+00 | 94 |

| IR14 | 172 | – | N | Ionotropic receptor IR64a | AIG51920.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 5.00E−76 | 68 |

| IR15 | 918 | 3 | Y | Ionotropic receptor 25a | AJD81628.1 | Helicoverpa assulta | 0.00E+00 | 97 |

| IR16 | 596 | – | N | Putative ionotropic receptor IR2 | AOE48001.1 | Athetis lepigone | 0.00E+00 | 82 |

| IR17 | 361 | – | N | Ionotropic receptor 75q.1 | AJD81638.1 | Helicoverpa assulta | 1.00E−179 | 75 |

| IR18 | 217 | – | N | Putative ionotropic receptor IR7d.2 | AOE47993.1 | Athetis lepigone | 2.00E−122 | 75 |

| IR19 | 343 | – | N | Ionotropic receptor IR75p.1 | AIG51922.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 0.00E+00 | 92 |

| IR20 | 175 | – | N | Putative ionotropic receptor IR75d | AOE47996.1 | Athetis lepigone | 5.00E−76 | 85 |

| IR21 | 523 | – | N | Ionotropic receptor 2 | AJD81622.1 | Helicoverpa assulta | 0.00E+00 | 68 |

| IR22 | 364 | – | N | Putative ionotropic receptor IR40a | AOE47989.1 | Athetis lepigone | 0.00E+00 | 92 |

| GUSTATORY RECEPTOR (GR) | ||||||||

| GR1 | 263 | – | N | Gustatory receptor 30 | KOB69617.1 | Operophtera brumata | 4.00E−14 | 26 |

| GR2 | 140 | – | N | Gustatory receptor 27 | DAA06383.1 | Bombyx mori | 6.00E−12 | 32 |

| GR3 | 207 | – | N | Gustatory receptor 58 | DAA06392.1 | Bombyx mori | 2.00E−18 | 26 |

| GR4 | 152 | – | N | Gustatory receptor | AIG51914.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 1.00E−94 | 87 |

| GR5 | 199 | – | N | Gustatory receptor 62 | DAA06394.1 | Bombyx mori | 2.00E−14 | 28 |

| GR6 | 151 | – | N | Gustatory receptor 58 | DAA06392.1 | Bombyx mori | 4.00E−05 | 47 |

| GR7 | 379 | 7 | Y | Gustatory receptor 11 | DAA06375.1 | Bombyx mori | 1.00E−57 | 33 |

| GR8 | 131 | – | N | Gustatory receptor 7 | DAA06374.1 | Bombyx mori | 9.00E−18 | 59 |

| GR9 | 230 | – | N | Gustatory receptor 12 | AJD81605.1 | Helicoverpa assulta | 4.00E−11 | 29 |

| GR10 | 444 | 7 | Y | Gustatory receptor | AIG51908.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 0.00E+00 | 95 |

| GR11 | 199 | – | N | Gustatory receptor 62 | DAA06394.1 | Bombyx mori | 5.00E−16 | 29 |

| GR12 | 446 | 7 | Y | Gustatory receptor 1 | AGK90010.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 0.00E+00 | 90 |

| GR13 | 464 | 7 | Y | Gustatory receptor | AIG51907.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 0.00E+00 | 96 |

| GR14 | 411 | 7 | Y | Gustatory Receptor | JAI18131.1 | Epiphyas postvittana | 3.00E−41 | 35 |

| GR15 | 377 | 6 | Y | Gustatory receptor 60 | NP_001124347.1 | Bombyx mori | 2.00E−12 | 25 |

| GR16 | 188 | – | N | Gustatory receptor | AIG51910.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 7.00E−121 | 88 |

| GR17 | 180 | – | N | Gustatory receptor 8 | ALM26257.1 | Athetis dissimilis | 7.00E−62 | 65 |

| GR18 | 339 | 3 | Y | Gustatory receptor 12 | AJD81605.1 | Helicoverpa assulta | 2.00E−13 | 28 |

| GR19 | 160 | – | N | Gustatory receptor for bitter taste 93a | XP_012550565.1 | Bombyx mori | 1.00E−68 | 66 |

| GR20 | 413 | 7 | Y | Gustatory receptor 53 | KOB74473.1 | Operophtera brumata | 1.00E−121 | 48 |

| GR21 | 200 | – | N | Gustatory receptor 60 | NP_001124347.1 | Bombyx mori | 9.00E−13 | 31 |

| GR22 | 275 | – | N | Gustatory receptor 50 | DAA06387.1 | Bombyx mori | 5.00E−90 | 49 |

| GR23 | 239 | – | N | Gustatory receptor 53 | DAA06389.1 | Bombyx mori | 7.00E−64 | 52 |

| GR24 | 136 | – | N | Gustatory receptor | AOG12970.1 | Eogystia hippophaecolus | 6.00E−22 | 81 |

| GR25 | 475 | 8 | Y | Gustatory receptor | AIG51909.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 0.00E+00 | 91 |

| GR26 | 364 | 7 | Y | Gustatory receptor 53 | KOB74473.1 | Operophtera brumata | 4.00E−115 | 51 |

| GR27 | 476 | 7 | Y | Gustatory receptor | AIG51911.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 0.00E+00 | 80 |

| GR28 | 258 | – | N | Gustatory receptor 53 | KOB74473.1 | Operophtera brumata | 1.00E−81 | 54 |

| GR29 | 503 | 7 | Y | Gustatory receptor | AGA04648.1 | Helicoverpa armigera | 0.00E+00 | 94 |

| GR30 | 341 | – | N | Gustatory receptor 7 | ALM26256.1 | Athetis dissimilis | 0.00E+00 | 79 |

TMD, transmembrane domain.

OBPs

We obtained a complete set of 24 different unigenes encoding putative OBPs in S. exigua (Table 2), of which 3 were newly identified. Sequence analysis revealed that 23 sequences were predicted to have full-length open reading frames (ORFs) and encoded 118–239 amino acids, but only 3 of the 23 SexiOBPs did not have signal peptide sequences (Table 2). The phylogenetic analysis showed that all 24 SexiOBPs were clustered in an OBP tree with Manduca sexta, B. mori, and Athetis lepigone (Figure 5), including 5 SexiOBPs (SexiPBP1-3, SexiGOBP1-2) clustered into the PBP/GOBP subfamily. The results suggest that these SexiOBPs belonged to the insect OBP family and should have the corresponding functions of the insect OBP (Poivet et al., 2012; Jeong et al., 2013; Pelosi et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2015a). The two new SexiOBPs (SexiOBP-N1 and SexiOBP-N3) encoded protein with high identities (97 and 99%) to OBPs in Spodoptera litura, respectively, indicating that SexiOBP-N1 and SexiOBP-N3 might have conserved functions in the two closely related species, such as recognizing the same host plant volatiles (Li et al., 2013; Gu et al., 2015). Therefore, they can be considered as target genes to simultaneously prevent and control these two pests (S. exigua and S. litura) in the future.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree of insect OBP. The S. exigua translated genes are shown in blue. Amino acid sequences used for the tree are given in Table S1. This tree was constructed using PhyML based on alignment results of ClustalX.

CSPs

Nineteen putative genes encoding CSPs were acquired in S. exigua based on the analysis results from the transcriptomes of the six chemosensory organs, of which four were newly attained (Table 2). Among the 19 SexiCSPs, 18 had full length ORFs with 4 conserved cysteines in the corresponding position and a predicted signal peptide at the N-terminus. The constructed insect CSP tree using protein sequences from S. exigua, M. sexta, B. mori, and A. lepigone (Figure 6) indicated that all 19 SexiCSPs were distributed along various branches and each clustered with at least 1 other moth ortholog. Thus, we inferred that these SexiCSPs should have a similar chemosensory function in insects, especially moths (Lartigue et al., 2002; Campanacci et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2014). Similar to SexiOBPs, we also found three of the four new SexiCSPs (SexiCSP-N2, SexiCSP-N3, and SexiCSP-N4) encoded proteins with high identities (99 and 100%) to CSPs in S. litura. This showed that they were very similar, maybe even the same CSPs, and might play the same role as OBPs in the two moths. In future studies, we intend to use the combination of in vitro (Jin et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014) and in vivo (Zhu et al., 2016; Dong et al., 2017; Ye et al., 2017) methods to explore the exact function of these conserved OBPs and CSPs in the two closely related species. In addition, we plan to study the exact functions of all the unknown functional OBPs and CSPs of S. exigua, which will help us define the odorant binding spectrum of each gene. This will provide potential behavioral disturbance agents to control the moths by using reverse chemical ecology methods (Zhu et al., 2017).

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic tree of insect CSP. The S. exigua translated genes are shown in blue. Amino acid sequences used for the tree are given in Table S1. This tree was constructed using PhyML based on alignment results of ClustalX.

ORs

Sixty-four different unigenes encoding putative ORs were identified by analyzing the transcriptome data of S. exigua, of which 57 were newly obtained (Table 3). A total of 28 out of 64 SexiORs contained full-length ORFs that encoded 351 to 473 amino acids with various transmembrane domains (TMD). The phylogenetic analysis showed that all 64 SexiORs were clustered in an OR tree with B. mori, D. plexippus, and H. armigera, with each clustering having at least one other moth ortholog (Figure 7). In accordance with previous studies (Liu et al., 2013), we also identified a chaperone and higher conserved insect OR—SexiOrco (Krieger et al., 2005; Nakagawa et al., 2005; Xu and Leal, 2013; Missbach et al., 2014) and four pheromone receptors (SexiOR6, 11, 13, and 16) (Table 3, Figure 7), which suggests that our sequencing and analysis methods were reliable. The results of the phylogenetic and sequence homology analyses showed that we were able to obtain the fifth PR gene of S. exigua, SexiOR59. Liu's research (Liu et al., 2013) found that only two PRs (SexiOR13 and SexiOR16) showed higher electrophysiological responses to the three sex pheromone components (Z9, E12-14:OAc, Z9-14:OAc, and Z9-14:OH) of S. exigua; however, no PRs displayed specific or higher response to the fourth pheromone component Z9, E12-14:OH. Therefore, further studies are required to determine whether SexiOR59 can respond highly or not to Z9, E12-14:OH or other pheromone components. Additionally, other researchers have found that several non-PR ORs could respond to host plant volatiles, such as SlitOR12 of S. litura (Zhang et al., 2015c), EpstOR1, and three from Epiphyas postvittana (Jordan et al., 2009). Therefore, some ORs of the 58 non-PR ORs in S. exigua might play a similar role in the chemosensation of the volatiles in host plants.

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic tree of insect OR. The S. exigua translated genes are shown in blue. Amino acid sequences used for the tree are given in Table S1. This tree was constructed using PhyML based on alignment results of ClustalX.

IRs

A total of 22 putative IR genes in S. exigua were identified, of which 16 were newly obtained (Table 3), and the SexiIRs number was similar to several other insects (Croset et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2014b; Xu et al., 2015). Only 7 of these genes had a full-length ORF (SexiIR2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, and 15) that encoded 542 to 918 amino acids with 3 or 4 TMD. We then constructed an insect IR tree using protein sequences from S. exigua, Drosophila melanogaster, B. mori, and Anopheles gambiae, which indicated that all 22 SexiIRs were clustered into 3 subfamilies of insect IR: 14 antennal IRs (SexiIR2, 4-6, 9, 11, 13, 14, 16-20, and 22), 6 divergent IRs (SexiIR1, 7, 8, 10, 12, and 21), and 2 IR25a/IR8a (SexiIR15 and 3), but no SexiIRs belonged to non-NMDA IGluRs subfamilies (Figure 8). This is similar to the conserved co-receptor Orco, where IR25a and IR8a of the insect were also co-receptors and could be co-expressed along with other IRs to ensure that insects could accurately detect external odorants via chemosensory organs (Abuin et al., 2011). Therefore, the co-receptors SexiIR15 (25a) and SexiIR3 (8a) might play the role of molecular chaperone to help with other SexiIRs functions.

Figure 8.

Phylogenetic tree of insect IR. The S. exigua translated genes are shown in blue. Amino acid sequences used for the tree are given in Table S1. This tree was constructed using PhyML based on alignment results of ClustalX.

GRs

We first identified 30 different unigenes encoding putative SexiGRs in the present study (Table 3). Sequence analysis revealed that 12 sequences were predicted to have full-length ORFs that encoded 339–503 amino acids with 3–8 TMD. This number of SexiGRs is higher than that of other species based on the transcriptome analysis, such as H. armigera (10 GRs) (Liu et al., 2014b), H. assulta (18 GRs) (Xu et al., 2015) and Hyphantria cunea (9 GRs) (Zhang et al., 2016), but lower than that of 3 species whose genomes have been sequenced, B. mori (69 GRs) (Wanner and Robertson, 2008; Sato et al., 2011), D. plexippus (58 GRs) (Zhan et al., 2011; Briscoe et al., 2013), and Heliconius melpomene (73 GRs) (Briscoe et al., 2013). This suggests that there is a high chance of identifying more SexiGR genes when the genome of S. exigua is successfully sequenced in the future.

An insect GR tree using protein sequences from S. exigua, B. mori, D. plexippus, and H. armigera was then constructed, and the tree showed that 3 SexiGRs (Sexi10, 13, and 25) were clustered in the CO2 Receptors subfamily, 6 SexiGRs (SexiGR4, 8, 12, 16, 27, and 30) were clustered in the Sugar Receptor subfamily, and 2 SexiGRs (SexiGR13 and 29) were clustered in the Fructose Receptor subfamily (Figure 9), indicating that these SexiGRs might be involved in the detection of CO2 (Jones et al., 2007; Kwon et al., 2007), sugar (Sato et al., 2011), and fructose (Jiang et al., 2015; Mang et al., 2016). Other SexiGRs, which do not belong to the three subfamilies, might be involved in other taste perception processes.

Figure 9.

Phylogenetic tree of insect GR. The S. exigua translated genes are shown in blue. Amino acid sequences used for the tree are given in Table S1. This tree was constructed using PhyML based on alignment results of ClustalX.

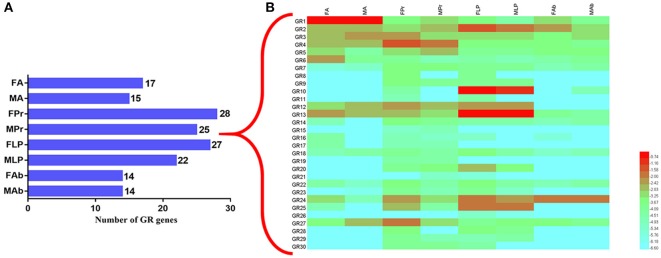

To better infer the potential functions of these SexiGRs, we applied the qPCR method to investigate the expression profiles of all SexiGRs in six chemosensory organs (FA, MA, FPr, MPr, FLP, and MLP) and two non-chemosensory organs (Female abdomen, FAb and Male abdomen, MAb) (Figure 10). The results showed that the organ with the highest SexiGRs expression was FPr (28 genes), followed by MPr (27 genes), FLP (25 genes), and MLP (22 genes), indicating that SexiGRs mainly exist within the gustatory organs, not the olfactory or non-chemosensory organs. This explains why the numbers of GR based on the antennae or non-gustatory organs transcriptome of other insects (Liu et al., 2014b; Xu et al., 2015) are lower than the SexiGRs in the present study. Additionally, we found 4, 16, 11, and 1 SexiGR genes that were highly expressed in the antennae, proboscises, labial palps, and abdomen of S. exigua, respectively, and some genes also showed differences in sex expression, which suggests that SexiGRs not only plays a pivotal role in gustatory processes (Jiang et al., 2015; Poudel et al., 2015), but might also be involved in olfactory (Agnihotri et al., 2016; Poudel et al., 2017) and other physiology processes (Xu et al., 2012; Ni et al., 2013). These results indicate that the proboscises and labial palps play more important roles in the taste perception process of than the olfactory organs do, which provides an important reference for future study of the taste perception mechanism in S. exigua as well as in other moths.

Figure 10.

Expression pattern of the SexiGRs. (A) The number of GR genes expressed in different organs of S. exigua. The digits of the histogram represent number of GRs. (B) relative expression levels of SexiGRs using qPCR. FA, female antennae; MA, male antennae; FPr, female proboscises; MPr, male proboscises; FLP, female labial palps; MLP, male labial palps; FAb, female abdomen; MAb, male abdomen.

In conclusion, 159 genes encoding putative chemosensory genes were obtained by analyzing six chemosensory organs of S. exigua. Our approach proved to be highly effective for the identification of chemosensory genes in S. exigua, for which genomic data are currently unavailable. As the first step toward understanding gene functions, we conducted a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of these genes and investigated all SexiGRs expression patterns, most of which were highly expressed in gustatory organs. The present study greatly improves the gene inventory for S. exigua and provides a foundation for future functional analyses of these crucial genes.

Author contributions

Y-NZ conceived and designed the experimental plan. Y-NZ, J-LQ, M-YL, and X-XX performed the experiment. Y-NZ, X-YZ, TX, and LS processed and analyzed the experiment data. J-WX and C-XL provided important suggestions to help modify the manuscript. Y-NZ wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bachelor students Cai-Yun Yin (Huaibei Normal University, China) for their help in collecting insects.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31501647), Natural Science Fund of Education Department of Anhui province, China (KJ2017A387, KJ2017B019 and KJ2017A384), Central Public-Interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (1610212016015, 1610212018010), Key Laboratory of Biology, Genetics and Breeding of Special Economic Animals and Plants, Ministry of Agriculture, China (Y2018PT14), Key Project of International Science and Technology Cooperation, National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFE0107500), The Science and Technology Innovation Project of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-ASTIP-2015-TRICAAS).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2018.00432/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abuin L., Bargeton B., Ulbrich M. H., Isacoff E. Y., Kellenberger S., Benton R. (2011). Functional architecture of olfactory ionotropic glutamate receptors. Neuron 69, 44–60. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acín P., Rosell G., Guerrero A., Quero C. (2010). Sex pheromone of the Spanish population of the beet armyworm Spodoptera exigua. J. Chem. Ecol. 36, 778–786. 10.1007/s10886-010-9817-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnihotri A. R., Roy A. A., Joshi R. S. (2016). Gustatory receptors in Lepidoptera: chemosensation and beyond. Insect Mol. Biol. 25, 519–529. 10.1111/imb.12246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anisimova M., Gil M., Dufayard J. F., Dessimoz C., Gascuel O. (2011). Survey of branch support methods demonstrates accuracy, power, and robustness of fast likelihood-based approximation schemes. Syst Biol 60, 685–699. 10.1093/sysbio/syr041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton R., Vannice K. S., Gomez-Diaz C., Vosshall L. B. (2009). Variant ionotropic glutamate receptors as chemosensory receptors in Drosophila. Cell 136, 149–162. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe A. D., Macias-Munoz A., Kozak K. M., Walters J. R., Yuan F., Jamie G. A., et al. (2013). Female behaviour drives expression and evolution of gustatory receptors in butterflies. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003620. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin S. A., Benes V., Garson J. A., Hellemans J., Huggett J., Kubista M., et al. (2009). The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 55, 611–622. 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanacci V., Lartigue A., Hallberg B. M., Jones T. A., Giudici-Orticoni M. T., Tegoni M., et al. (2003). Moth chemosensory protein exhibits drastic conformational changes and cooperativity on ligand binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 5069–5074. 10.1073/pnas.0836654100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao D., Liu Y., Wei J., Liao X., Walker W. B., Li J., et al. (2014). Identification of candidate olfactory genes in Chilo suppressalis by antennal transcriptome analysis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 10, 846–860. 10.7150/ijbs.9297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyne P. J., Warr C. G., Carlson J. R. (2000). Candidate taste receptors in Drosophila. Science 287, 1830–1834. 10.1126/science.287.5459.1830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crasto C. J. (2013). Olfactory Receptors, in Methods in Molecular Biology, ed Walker J. M. (Birmingham, AL: Humana Press; ), 211–214. [Google Scholar]

- Croset V., Rytz R., Cummins S. F., Budd A., Brawand D., Kaessmann H., et al. (2010). Ancient protostome origin of chemosensory ionotropic glutamate receptors and the evolution of insect taste and olfaction. PLoS Genet. 6:e1001064. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong K., Sun L., Liu J. T., Gu S. H., Zhou J. J., Yang R. N., et al. (2017). RNAi-Induced electrophysiological and behavioral changes reveal two pheromone binding proteins of Helicoverpa armigera involved in the perception of the main sex pheromone component Z11-16:Ald. J. Chem. Ecol. 43, 207–214. 10.1007/s10886-016-0816-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field L. M., Pickett J. A., Wadhams L. J. (2000). Molecular studies in insect olfaction. Insect Mol. Biol. 9, 545–551. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong D. P., Zhang H. J., Zhao P., Lin Y., Xia Q. Y., Xiang Z. H. (2007). Identification and expression pattern of the chemosensory protein gene family in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 37, 266–277. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong D. P., Zhang H. J., Zhao P., Xia Q. Y., Xiang Z. H. (2009). The odorant binding protein gene family from the genome of silkworm, Bombyx mori. BMC Genomics 10:332. 10.1186/1471-2164-10-332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr M. G., Haas B. J., Yassour M., Levin J. Z., Thompson D. A., Amit I., et al. (2011). Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652. 10.1038/nbt.1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosse-Wilde E., Kuebler L. S., Bucks S., Vogel H., Wicher D., Hansson B. S. (2011). Antennal transcriptome of Manduca sexta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 7449–7454. 10.1073/pnas.1017963108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu S. H., Wu K. M., Guo Y. Y., Pickett J. A., Field L. M., Zhou J. J., et al. (2013). Identification of genes expressed in the sex pheromone gland of the black cutworm Agrotis ipsilon with putative roles in sex pheromone biosynthesis and transport. BMC Genomics 14:636. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu S. H., Zhou J. J., Gao S., Wang D. H., Li X. C., Guo Y. Y., et al. (2015). Identification and comparative expression analysis of odorant binding protein genes in the tobacco cutworm Spodoptera litura. Sci Rep 5:13800. 10.1038/srep13800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S., Dufayard J. F., Lefort V., Anisimova M., Hordijk W., Gascuel O. (2010). New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59, 307–321. 10.1093/sysbio/syq010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Cheng T., Chen Z., Jiang L., Guo Y., Liu J., et al. (2017). Expression map of a complete set of gustatory receptor genes in chemosensory organs of Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 82, 74–82. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2017.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He P., Zhang Y. F., Hong D. Y., Wang J., Wang X. L., Zuo L. H., et al. (2017). A reference gene set for sex pheromone biosynthesis and degradation genes from the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella, based on genome and transcriptome digital gene expression analyses. BMC Genomics 18:219. 10.1186/s12864-017-3592-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iovinella I., Bozza F., Caputo B., Della Torre A., Pelosi P. (2013). Ligand-binding study of Anopheles gambiae chemosensory proteins. Chem. Senses 38, 409–419. 10.1093/chemse/bjt012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquin-Joly E., Merlin C. (2004). Insect olfactory receptors: contributions of molecular biology to chemical ecology. J. Chem. Ecol. 30, 2359–2397. 10.1007/s10886-004-7941-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong Y. T., Shim J., Oh S. R., Yoon H. I., Kim C. H., Moon S. J., et al. (2013). An odorant-binding protein required for suppression of sweet taste by bitter chemicals. Neuron 79, 725–737. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X. J., Ning C., Guo H., Jia Y. Y., Huang L. Q., Qu M. J., et al. (2015). A gustatory receptor tuned to d-fructose in antennal sensilla chaetica of Helicovera armigera. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 60, 39–46. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2015.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J. Y., Li Z. Q., Zhang Y. N., Liu N. Y., Dong S. L. (2014). Different roles suggested by sex-biased expression and pheromone binding affinity among three pheromone binding proteins in the pink rice borer, Sesamia inferens (Walker) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Insect Physiol. 66, 71–79. 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2014.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones W. D., Cayirlioglu P., Kadow I. G., Vosshall L. B. (2007). Two chemosensory receptors together mediate carbon dioxide detection in Drosophila. Nature 445, 86–90. 10.1038/nature05466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan M. D., Anderson A., Begum D., Carraher C., Authier A., Marshall S. D., et al. (2009). Odorant receptors from the light brown apple moth (Epiphyas postvittana) recognize important volatile compounds produced by plants. Chem. Senses 34, 383–394. 10.1093/chemse/bjp010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A., Larsson B., von Heijne G., Sonnhammer E. L. (2001). Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305, 567–580. 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger J., Grosse-Wilde E., Gohl T., Breer H. (2005). Candidate pheromone receptors of the silkmoth Bombyx mori. Eur. J. Neurosci. 21, 2167–2176. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04058.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon J. Y., Dahanukar A., Weiss L. A., Carlson J. R. (2007). The molecular basis of CO2 reception in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 3574–3578. 10.1073/pnas.0700079104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai T., Su J. (2011). Assessment of resistance risk in Spodoptera exigua (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) to chlorantraniliprole. Pest Manag. Sci. 67, 1468–1472. 10.1002/ps.2201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin M. A., Blackshields G., Brown N. P., Chenna R., McGettigan P. A., McWilliam H., et al. (2007). Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lartigue A., Campanacci V., Roussel A., Larsson A. M., Jones T. A., Tegoni M., et al. (2002). X-ray structure and ligand binding study of a moth chemosensory protein. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32094–32098. 10.1074/jbc.M204371200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le S. Q., Gascuel O. (2008). An improved general amino acid replacement matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 1307–1320. 10.1093/molbev/msn067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal W. S. (2013). Odorant reception in insects: roles of receptors, binding proteins, and degrading enzymes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 58, 373–391. 10.1146/annurev-ento-120811-153635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legeai F., Malpel S., Montagne N., Monsempes C., Cousserans F., Merlin C., et al. (2011). An expressed sequence tag collection from the male antennae of the noctuid moth Spodoptera littoralis: a resource for olfactory and pheromone detection research. BMC Genomics 12:86. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Zhang H., Guan R., Miao X. (2013). Identification of differential expression genes associated with host selection and adaptation between two sibling insect species by transcriptional profile analysis. BMC Genomics 14:582. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Zhu H., Ruan J., Qian W., Fang X., Shi Z., et al. (2010). De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing. Genome Res. 20, 265–272. 10.1101/gr.097261.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. M., Zhu X. Y., Wang Z. Q., Wang Y., He P., Chen G., et al. (2015). Candidate chemosensory genes identified in Colaphellus bowringi by antennal transcriptome analysis. BMC Genomics 16:1028. 10.1186/s12864-015-2236-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. Q., Luo Z. X., Cai X. M., Bian L., Xin Z. J., Liu Y., et al. (2017). Chemosensory gene families in Ectropis grisescens and candidates for detection of type-II sex pheromones. Front. Physiol. 8:953. 10.3389/fphys.2017.00953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Liu Y., Guo M., Cao D., Dong S., Wang G. (2014a). Narrow tuning of an odorant receptor to plant volatiles in Spodoptera exigua (Hubner). Insect Mol. Biol. 23, 487–496. 10.1111/imb.12096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Liu Y., Walker W. B., Dong S., Wang G. (2013). Identification and functional characterization of sex pheromone receptors in beet armyworm Spodoptera exigua (Hübner). Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43, 747–754. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2013.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N. Y., Xu W., Papanicolaou A., Dong S. L., Anderson A. (2014b). Identification and characterization of three chemosensory receptor families in the cotton bollworm Helicoverpa armigera. BMC Genomics 15:597. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N. Y., Yang F., Yang K., He P., Niu X. H., Xu W., et al. (2015a). Two subclasses of odorant-binding proteins in Spodoptera exigua display structural conservation and functional divergence. Insect Mol. Biol. 24, 167–182. 10.1111/imb.12143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N. Y., Zhang T., Ye Z. F., Li F., Dong S. L. (2015b). Identification and characterization of candidate chemosensory gene families from Spodoptera exigua developmental transcriptomes. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 11, 1036–1048. 10.7150/ijbs.12020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S. J., Liu N. Y., He P., Li Z. Q., Dong S. L., Mu L. F. (2012). Molecular characterization, expression patterns, and ligand-binding properties of two odorant-binding protein genes from Orthaga achatina (Butler) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 80, 123–139. 10.1002/arch.21036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mang D., Shu M., Tanaka S., Nagata S., Takada T., Endo H., et al. (2016). Expression of the fructose receptor BmGr9 and its involvement in the promotion of feeding, suggested by its co-expression with neuropeptide F1 in Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 75, 58–69. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2016.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna M. P., Hekmat-Scafe D. S., Gaines P., Carlson J. R. (1994). Putative Drosophila pheromone-binding proteins expressed in a subregion of the olfactory system. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 16340–16347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missbach C., Dweck H. K., Vogel H., Vilcinskas A., Stensmyr M. C., Hansson B. S., et al. (2014). Evolution of insect olfactory receptors. Elife 3:e02115. 10.7554/eLife.02115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller P. Y., Janovjak H., Miserez A. R., Dobbie Z. (2002). Processing of gene expression data generated by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Biotechniques 32, 1372–1374, 1376, 1378–1379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T., Sakurai T., Nishioka T., Touhara K. (2005). Insect sex-pheromone signals mediated by specific combinations of olfactory receptors. Science 307, 1638–1642. 10.1126/science.1106267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni L., Bronk P., Chang E. C., Lowell A. M., Flam J. O., Panzano V. C., et al. (2013). A gustatory receptor paralogue controls rapid warmth avoidance in Drosophila. Nature 500, 580–584. 10.1038/nature12390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier V., Monsempes C., Francois M. C., Poivet E., Jacquin-Joly E. (2011). Candidate chemosensory ionotropic receptors in a Lepidoptera. Insect Mol. Biol. 20, 189–199. 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2010.01057.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelosi P., Calvello M., Ban L. (2005). Diversity of odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins in insects. Chem. Senses 30(Suppl. 1), i291–i292. 10.1093/chemse/bjh229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelosi P., Iovinella I., Felicioli A., Dani F. R. (2014). Soluble proteins of chemical communication: an overview across arthropods. Front. Physiol. 5:320. 10.3389/fphys.2014.00320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelosi P., Iovinella I., Zhu J., Wang G., Dani F. R. (2018). Beyond chemoreception: diverse tasks of soluble olfactory proteins in insects. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 93, 184–200. 10.1111/brv.12339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelosi P., Zhou J. J., Ban L. P., Calvello M. (2006). Soluble proteins in insect chemical communication. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 63, 1658–1676. 10.1007/s00018-005-5607-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen T. N., Brunak S., von Heijne G., Nielsen H. (2011). SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat. Methods 8, 785–786. 10.1038/nmeth.1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picimbon J. F., Gadenne C. (2002). Evolution of noctuid pheromone binding proteins: identification of PBP in the black cutworm moth, Agrotis ipsilon. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 32, 839–846. 10.1016/S0965-1748(01)00172-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poivet E., Rharrabe K., Monsempes C., Glaser N., Rochat D., Renou M., et al. (2012). The use of the sex pheromone as an evolutionary solution to food source selection in caterpillars. Nat. Commun. 3:1047. 10.1038/ncomms2050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poudel S., Kim Y., Kim Y. T., Lee Y. (2015). Gustatory receptors required for sensing umbelliferone in Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 66, 110–118. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2015.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poudel S., Kim Y., Kwak J., Jeong S., Lee Y. (2017). Gustatory receptor 22e is essential for sensing chloroquine and strychnine in Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 88, 30–36. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray A., van Naters W. G., Carlson J. R. (2014). Molecular determinants of odorant receptor function in insects. J. Biosci. 39, 555–563. 10.1007/s12038-014-9447-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimal S., Lee Y. (2018). The multidimensional ionotropic receptors of Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Mol. Biol. 27, 1–7. 10.1111/imb.12347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytz R., Croset V., Benton R. (2013). Ionotropic receptors (IRs): chemosensory ionotropic glutamate receptors in Drosophila and beyond. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43, 888–897. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2013.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K., Tanaka K., Touhara K. (2011). Sugar-regulated cation channel formed by an insect gustatory receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 11680–11685. 10.1073/pnas.1019622108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon P. (2003). Q-Gene: processing quantitative real-time RT-PCR data. Bioinformatics 19, 1439–1440. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey J. D. (2003). The positive false discovery rate: a Bayesian interpretation and the q-value. Ann. Stat. 31, 2013–2035. 10.1214/aos/1074290335 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suh E., Bohbot J., Zwiebel L. J. (2014). Peripheral olfactory signaling in insects. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 6, 86–92. 10.1016/j.cois.2014.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Wang Q., Yang S., Wang Q., Zhang Z., Khashaveh A., et al. (2017). Functional analysis of female-biased odorant binding protein 6 for volatile and nonvolatile host compounds in Adelphocoris lineolatus (Goeze). Insect Mol. Biol. 26, 601–615. 10.1111/imb.12322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Xiao H. J., Gu S. H., Guo Y. Y., Liu Z. W., Zhang Y. J. (2014). Perception of potential sex pheromones and host-associated volatiles in the cotton plant bug, Adelphocoris fasciaticollis (Hemiptera: Miridae): morphology and electrophysiology. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 49, 43–57. 10.1007/s13355-013-0223-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K., Uda Y., Ono Y., Nakagawa T., Suwa M., Yamaoka R., et al. (2009). Highly selective tuning of a silkworm olfactory receptor to a key mulberry leaf volatile. Curr. Biol. 19, 881–890. 10.1016/j.cub.2009.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt R. G. (2003). Biochemical diversity of odor detection:OBPs, ODEs and SNMPs, in Insect Pheromone Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, eds Blomquist G. J., Vogt R. G. (London: Elsevier Academic Press; ), 397–451. [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Feng Z., Wang X., Wang X., Zhang X. (2010). DEGseq: an R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics 26, 136–138. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner K. W., Robertson H. M. (2008). The gustatory receptor family in the silkworm moth Bombyx mori is characterized by a large expansion of a single lineage of putative bitter receptors. Insect Mol. Biol. 17, 621–629. 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2008.00836.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y. H., Zhang Y. N., Hou X. Q., Li F., Dong S. L. (2015). Large number of putative chemoreception and pheromone biosynthesis genes revealed by analyzing transcriptome from ovipositor-pheromone glands of Chilo suppressalis. Sci. Rep. 5:7888. 10.1038/srep07888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiu W. M., Dong S. L. (2007). Molecular characterization of two pheromone binding proteins and quantitative analysis of their expression in the beet armyworm, Spodoptera exigua Hübner. J. Chem. Ecol. 33, 947–961. 10.1007/s10886-007-9277-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiu W. M., Zhou Y. Z., Dong S. L. (2008). Molecular characterization and expression pattern of two pheromone-binding proteins from Spodoptera litura (Fabricius). J. Chem. Ecol. 34, 487–498. 10.1007/s10886-008-9452-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P., Leal W. S. (2013). Probing insect odorant receptors with their cognate ligands: insights into structural features. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 435, 477–482. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Papanicolaou A., Liu N. Y., Dong S. L., Anderson A. (2015). Chemosensory receptor genes in the Oriental tobacco budworm Helicoverpa assulta. Insect Mol. Biol. 24, 253–263. 10.1111/imb.12153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Zhang H. J., Anderson A. (2012). A sugar gustatory receptor identified from the foregut of cotton bollworm Helicoverpa armigera. J. Chem. Ecol. 38, 1513–1520. 10.1007/s10886-012-0221-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y. L., He P., Zhang L., Fang S. Q., Dong S. L., Zhang Y. J., et al. (2009). Large-scale identification of odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins from expressed sequence tags in insects. BMC Genomics 10:632. 10.1186/1471-2164-10-632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S., Cao D., Wang G., Liu Y. (2017). Identification of genes involved in chemoreception in Plutella xyllostella by antennal transcriptome analysis. Sci. Rep. 7:11941. 10.1038/s41598-017-11646-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Z. F., Liu X. L., Han Q., Liao H., Dong X. T., Zhu G. H., et al. (2017). Functional characterization of PBP1 gene in Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) by using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Sci. Rep. 7:8470. 10.1038/s41598-017-08769-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan S., Merlin C., Boore J. L., Reppert S. M. (2011). The monarch butterfly genome yields insights into long-distance migration. Cell 147, 1171–1185. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. J., Anderson A. R., Trowell S. C., Luo A. R., Xiang Z. H., Xia Q. Y. (2011). Topological and functional characterization of an insect gustatory receptor. PLoS ONE 6:e24111. 10.1371/journal.pone.0024111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Walker W. B., Wang G. (2015a). Pheromone reception in moths: from molecules to behaviors. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 130, 109–128. 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2014.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Wang B., Dong S., Cao D., Dong J., Walker W. B., et al. (2015b). Antennal transcriptome analysis and comparison of chemosensory gene families in two closely related noctuidae moths, Helicoverpa armigera and H. assulta. PLoS ONE 10:e0117054. 10.1371/journal.pone.0117054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Yan S., Liu Y., Jacquin-Joly E., Dong S., Wang G. (2015c). Identification and functional characterization of sex pheromone receptors in the common cutworm (Spodoptera litura). Chem. Senses 40, 7–16. 10.1093/chemse/bju052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. W., Kang K., Jiang S. C., Zhang Y. N., Wang T. T., Zhang J., et al. (2016). Analysis of the antennal transcriptome and insights into olfactory genes in Hyphantria cunea (Drury). PLoS ONE 11:e0164729. 10.1371/journal.pone.0164729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Wang B., Grossi G., Falabella P., Liu Y., Yan S., et al. (2017). Molecular basis of alarm pheromone detection in aphids. Curr. Biol. 27, 55–61. 10.1016/j.cub.2016.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. N., Jin J. Y., Jin R., Xia Y. H., Zhou J. J., Deng J. Y., et al. (2013). Differential expression patterns in chemosensory and non-chemosensory tissues of putative chemosensory genes identified by transcriptome analysis of insect pest the purple stem borer Sesamia inferens (Walker). PLoS ONE 8:e69715. 10.1371/journal.pone.0069715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. N., Ye Z. F., Yang K., Dong S. L. (2014). Antenna-predominant and male-biased CSP19 of Sesamia inferens is able to bind the female sex pheromones and host plant volatiles. Gene 536, 279–286. 10.1016/j.gene.2013.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. N., Zhang L. W., Chen D. S., Sun L., Li Z. Q., Ye Z. F., et al. (2017a). Molecular identification of differential expression genes associated with sex pheromone biosynthesis in Spodoptera exigua. Mol. Genet. Genomics 292, 795–809. 10.1007/s00438-017-1307-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. N., Zhu X. Y., Ma J. F., Dong Z. P., Xu J. W., Kang K., et al. (2017b). Molecular identification and expression patterns of odorant binding protein and chemosensory protein genes in Athetis lepigone (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). PeerJ 5:e3157. 10.7717/peerj.3157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J. J. (2010). Odorant-binding proteins in insects. Vitam. Horm. 83, 241–272. 10.1016/S0083-6729(10)83010-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G. H., Xu J., Cui Z., Dong X. T., Ye Z. F., Niu D. J., et al. (2016). Functional characterization of SlitPBP3 in Spodoptera litura by CRISPR/Cas9 mediated genome editing. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 75, 1–9. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Arena S., Spinelli S., Liu D., Zhang G., Wei R., et al. (2017). Reverse chemical ecology: Olfactory proteins from the giant panda and their interactions with putative pheromones and bamboo volatiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, E9802–E9810. 10.1073/pnas.1711437114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J. Y., Zhang L. F., Ze S. Z., Wang D. W., Yang B. (2013). Identification and tissue distribution of odorant binding protein genes in the beet armyworm, Spodoptera exigua. J. Insect Physiol. 59, 722–728. 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2013.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.