Highlights

-

•

Benign strictures of the biliary system are challenging, uncommon conditions requiring multidisciplinary team treatment.

-

•

The complex nature of the stricture required a combined interventional radiologic and surgical approach.

-

•

Injury to the intrahepatic biliary ductal confluence is rarely fatal, but, associated injuries cause severe morbidity.

-

•

We describe an innovative multidisciplinary approach to the repair of this rare injury.

Keywords: Combined approach, Interventional radiology, Hepatobiliary surgery, Complex traumatic hilar biliary stricture, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Benign strictures of the biliary system are challenging and uncommon conditions requiring a multidisciplinary team for appropriate management.

Presentation of case

The patient is a 32-year-old male that developed a hilar stricture as sequelae of a gunshot wound. Due to the complex nature of the stricture and scarring at the porta hepatis a combined interventional radiologic and surgical approach was carried out to approach the hilum of the right and left hepatic ducts. The location of this stricture was found by ultrasound guidance intraoperatively using a balloon tipped catheter placed under fluoroscopy in the interventional radiology suite prior to surgery. This allowed the surgeons to select the line of parenchymal transection for best visualization of the stricture. A left hepatectomy was performed, the internal stent located and the right hepatic duct opened tangentially to allow a side-to-side Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy (a Puestow-like anastomosis).

Discussion

Injury to the intrahepatic biliary ductal confluence is rarely fatal, however, the associated injuries lead to severe morbidity as seen in this example. Management of these injuries poses a considerable challenge to the surgeon and treating physicians.

Conclusion

Here we describe an innovative multi-disciplinary approach to the repair of this rare injury.

1. Background

Strictures of the bile ducts are a challenging, uncommon condition that requires a multidisciplinary team for appropriate and safe management. Up to 30% of patients with benign strictures have prolonged, complicated courses requiring multiple services for management leading to significant healthcare costs [1]. The majority of recommendations for treating benign biliary strictures relate to common causes of biliary stricture including injury from ischemia or trauma, injury due to chronic pancreatitis, and strictures after liver transplant [2]. Throughout the years, there has been little attention to biliary strictures caused by penetrating trauma, specifically gunshots [3]. We present a case of a patient who sustained a gunshot wound to his abdomen and subsequently developed a hilar stricture that extended into the main right hepatic duct with eventual treatment involving a combined surgical and interventional radiologic (IR) approach. Our work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [4].

2. Case presentation

A 32-year-old previously healthy male sustained a gunshot wound to the abdomen. Permission was obtained allowing discussion and publication of this case. The bullet went through the right lobe of the liver and anteriorly through the left lobe. The bullet caused injuries to the gallbladder, duodenum, and left diaphragm. The patient underwent emergency surgery noting blood but no bile upon entering the abdomen. Multiple grade II liver lacerations were appreciated and the liver was packed. The patient underwent a cholecystectomy, repair of duodenal injury, repair of diaphragm and placement of chest tube. The patient recovered from surgery and discharged on postoperative (POD) 5, however, on POD 8–he returned with increasing abdominal pain and was found to have a bile leak. The patient underwent multiple radiologic and endoscopic procedures showing contrast extravasation from the region of the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts or most proximal common hepatic duct (Fig. 1). The bile leak was controlled with placement of bilateral percutaneous internal/external biliary stents. In the months following, the patient was found to have a stricture at the confluence of the hepatic ducts. Multiple attempts to treat the stricture with balloon dilatation were unsuccessful, rendering the patient catheter dependent. The patient was referred to a hepatobiliary surgeon approximately 1 year after initial injury. After evaluating the stricture with multiple studies, it appeared that the patient had a high grade stenosis at the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts that extended proximally into the main right hepatic duct but did not involve the junction of the anterior and posterior sectoral ducts (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogram demonstrating a bile leak from the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts or proximal common hepatic duct.

Fig. 2.

Abnormality at the bifurcation of the common hepatic duct extending into the proximal right and left hepatic ducts with evidence of high-grade stenosis.

Fig. 3.

Cholangiography of the right hepatic ductal system demonstrating a high-grade residual stenosis at the junction of the posterior sectoral duct, anterior sectoral duct and left bile duct.

Fig. 4.

Cholangiography of the right hepatic ductal system demonstrating a high-grade residual stenosis at the junction of the posterior sectoral duct, anterior sectoral duct and left bile duct.

The patient was lost to follow-up returning due to weight loss of 35 lbs, constant abdominal pain, nausea, and severe fatigue with inability to perform many functions of daily living. It was recognized surgery with a major hepatectomy would be required but the dissection would be difficult due to distortion of the anatomy at the porta hepatis and confluence of the right and left bile ducts. After discussing the case at our multidisciplinary hepatobiliary oncology conference, a decision was made to treat his stricture operatively using a combined IR and surgical approach. It was determined that the best approach would be to resect the left lobe of the liver to obtain access to the proximal right hepatic stricture. To assist intraoperatively with localizing this area, we used the precision of image guided catheter placement preoperatively followed by intraoperative ultrasound.

3. Treatment

The patient went to the IR suite and underwent removal of his right percutaneous internal/external biliary drain over a wire. Two vascular sheaths were placed through the existing tract and a repeat cholangiography was performed. Using the existing wire access and through the vascular sheath two balloons were inserted, placed in the duodenum and positioned just proximal to the stricture in the right hepatic duct. Sheaths were secured and the patient was transported to the operating room.

A right subcostal incision was made. Once the liver was mobilized from the diaphragm, the left internal/external stent was cut from inside the abdomen, freeing the liver (Fig. 5). The bile duct in the porta hepatis was identified and mobilized from the portal vein. An intraoperative ultrasound of the liver was performed while the interventional radiologist manipulated the vascular sheaths. One of the sheaths had a wire through it with a balloon. The balloon was inflated and visualized on ultrasound. With balloon visualization, the parenchymal transection was determined including segments 2, 3, 4b and a portion of 4a. The transection was performed using a clamp-crush technique. The left hepatic duct was noted, with a stent. The stent was removed and the left main pedicle was divided with a linear stapler. Both sheaths were identified passing through the common hepatic duct (Fig. 6). A ductotomy was made in the left hepatic duct and extended to the right hepatic duct immediately proximal to the stricture (Fig. 7). The common bile duct was mobilized and divided distally, and the distal end was closed with 3-0 PDS suture. The common hepatic duct was resected such that the back wall of the confluence and the right hepatic duct orifice, which had the sheaths coming through it, remained. The sheath was removed with the guide-wire in place. An 18-French internal/external drain was threaded over the guide-wire to create the anastomosis. Once the drain was within the liver, the guide-wire was removed.

Fig. 5.

The liver was mobilized from the diaphragm, and the left internal/external stent was cut from inside the abdomen, freeing the liver.

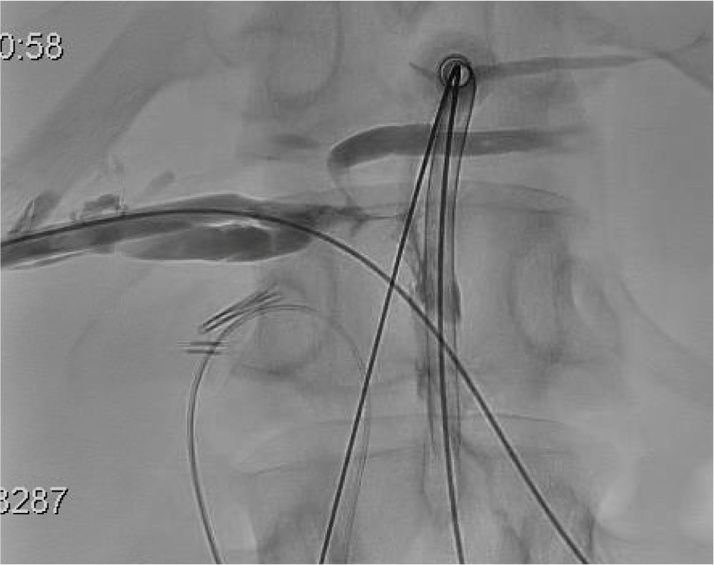

Fig. 6.

Both sheaths were identified passing through the common hepatic duct.

Fig. 7.

A ductotomy was made in the left hepatic duct and extended to the right hepatic duct immediately proximal to the stricture.

A latero-lateral bilioenteric single-layer anastomosis was performed with 3-0 PDS suture in a continuous fashion (Puestow-type, pancreaticojejunal anastomosis for chronic pancreatitis). This type of anastomosis was performed due to the need to encompass the long posterior wall of the right hepatic duct, and the area of the ductal confluence that included the bile duct draining segment IV of the liver (Fig. 8). This was a wide-mouth anastomosis approximately 4 cm in length (Fig. 9). The biliary drain was passed through the anastomosis into the jejunum. A side-to-side jejunojejunostomy was performed between the Roux-limb and the alimentary limb. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged on POD 6, tolerating regular diet with minimal incisional pain.

Fig. 8.

A latero-lateral bilioenteric single-layer anastomosis was performed with 3-0 PDS suture in a continuous fashion (Puestow-type anastomosis).

Fig. 9.

A latero-lateral bilioenteric single-layer anastomosis was performed with 3-0 PDS suture in a continuous fashion (Puestow-type anastomosis).

4. Discussion

Nonsurgical traumatic injuries of the extra and intra hepatic bile ducts are rare [[5], [6]], and account for 0.5% of abdominal injuries in adults [[7], [8]]. Injury to the ducts is rarely fatal, however, associated injuries lead to severe morbidity. Management of these injuries poses a considerable challenge. Due to the severity of other injuries in our patient on initial presentation his ductal injuries were not initially identified. If a bile duct injury is suspected and/or diagnosed at the time of a traumatic injury, it is recommended to drain the patient adequately, manage any other injuries and wait to perform definitive repair of the biliary injury [9]. Typically internal/external drainage will provide adequate drainage for patient recovery.

There is no consensus on optimal management of injuries/strictures involving either the hepatic ductal confluence or more proximally the secondary biliary radicles. Most reports of traumatic biliary injury described are due to iatrogenic injuries following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Initially, many recommend minimally invasive procedures including percutaneous radiological or endoscopic interventions. Literature states, that radiological success with transhepatic stenting of the damaged biliary tract is approximately 40%–85% [10]. If a biliary stricture cannot be fixed endoscopically, a percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography may be required. If the stricture is easily crossed, it can usually be treated with an internal/external drain and serial dilations. This is left for 6 months allowing for the ducts to heal with the goal of placing a large bore catheter, 16–18Fr [[11], [12]]. If the stricture is high-grade, the patient requires external drainage, as the stricture cannot be traversed. Over the next months of successful drainage, access of the lesion can again be attempted, and if possible a stent may be placed across the stricture with serial dilations. When these techniques fail, surgical management is considered, however prior to any biliary repair, high quality imaging is paramount to determine the biliary anatomy [[11], [12]].

Intraoperative ultrasound (IUS) has also become more widely used in hepatobiliary surgery due to its accuracy in defining difficult anatomy intraoperatively. Although most data is related to tumor resection, we were able to define the hepatic anatomy precisely using IUS with IR guidance. IUS can more accurately determine difficult hepatic anatomy compared to other preoperative methods such as CT or MRI [13]. Aziz et. al described using IUS to detect common bile duct stones when performing cholecystectomy. Meta-analysis showed that IUS is very accurate in detecting choledocholithiasis and IUS could help accurately determine correct biliary anatomy [14].

Injuries/strictures of the hepatic ductal confluence are similar to type III and IV strictures of the Bismuth-Corlette classification of malignant strictures [15]. The principles of obtaining adequate biliary-enteric drainage for both types is similar and involves three fundamental principles: identifying healthy bile duct mucosa proximal to the injury, Roux-en-Y anastomosis 40 cm proximal to the enteroenterostomy, and direct mucosa-to-mucosa anastomosis with interrupted, absorbable sutures [[16], [17]]. The surgical options to manage proximal biliary strictures include 1) enteric drainage to the confluence of the main right and left hepatic ducts without parenchymal resection, 2) enteric drainage to either the right or left hepatic ducts with parenchymal resection, or 3) liver transplantation [[18], [19]].

The patient described in the case had a rare, nonsurgical, traumatic cause of biliary stricture from a gunshot. We described an innovative collaborative approach to repair this injury. Modern hepatobiliary surgical centers involve both liver surgeons and interventional radiologists often working separately to solve specific problems. Recently it has been recognized that complex hepatobiliary problems can be solved using novel approaches that involve these two disciplines. We recently reported a novel combined surgical and IR approach to manage a bile duct fistula that resulted from an extended left hepatectomy in a patient with an unrecognized anomalous right posterior sectoral duct [20]. This collaboration has proved successful and beneficial to patient’s survival and success.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Sources of funding

None

Ethical approval

Case Reports do not require ethics committee approval at our institution. Ethical approval has been exempted by my institution

Consent

We have written consent for the publication of this case report.

Author contribution

Rachel E. NeMoyer MD, Mihir M. Shah MD, Omar Hasan MD, John L. Nosher MD, and Darren R. Carpizo MD, PhD had integral parts in the concept and design of the surgery, writing the paper and editing the images.

Registration of research studies

n/a > Case Report

Guarantor

Rachel NeMoyer and Darren Carpizo.

Footnotes

All authors have approved the final article should be true and included in the disclosure.

References

- 1.Dadhwal U.S., Kumar V. Benign bile duct strictures. Med. J., Armed Forces India. 2012;68(July (3)):299. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costamagna G., Boškoski I. Current treatment of benign biliary strictures. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2013;26(1):37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ban J.L., Hirose F.M., Benfield J.R. Foreign bodies of the biliary tract: report of two patients and a review of the literature. Ann. Surg. 1972;176(July (1)):102. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197207000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;(September (6)) doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitahama A.K., Elliott L.F., Overby J.L., Webb W.R. The extrahepatic biliary tract injury: perspective in diagnosis and treatment. Ann. Surg. 1982;196(November (5)):536. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198211000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feliciano D.V. Management of traumatic retroperitoneal hematoma. Ann. Surg. 1990;211(February (2)):109. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199002000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Posner M.C., Moore E.E. Extrahepatic biliary tract injury: operative management plan. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 1985;25(September 1 (9)):833–837. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198509000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maheshwari M., Chawla A., Dalvi A., Thapar P., Raut A. Bullet in the common hepatic duct: a cause of obstructive jaundice. Clin. Radiol. 2003;58(April 30 (4)):334–335. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(02)00518-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lillemoe K.D., Melton G.B., Cameron J.L., Pitt H.A., Campbell K.A., Talamini M.A., Sauter P.A., Coleman J., Yeo C.J. Postoperative bile duct strictures: management and outcome in the 1990. Ann. Surg. 2000;232(September (3)):430. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200009000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jabłońska B., Lampe P. Iatrogenic bile duct injuries: etiology, diagnosis and management. World J. Gastroenterol.: WJG. 2009;15(September 7 (33)):4097. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santibánes E., Ardiles V., Pekolj J. Complex bile duct injuries: management. HPB. 2008;10(February 1 (1)):4–12. doi: 10.1080/13651820701883114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DePietro D.M., Shlansky-Goldberg R.D., Soulen M.C., Stavropoulos S.W., Mondschein J.I., Dagli M.S., Itkin M., Clark T.W., Trerotola S.O. Long-term outcomes of a benign biliary stricture protocol. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2015;26(July 31 (7)):1032–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schirmer B.D. 2001. Intra-operative and Laparoscopic Ultrasound. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aziz O., Ashrafian H., Jones C., Harling L., Kumar S., Garas G. Laparoscopic ultrasonography versus intra-operative cholangiogram for the detection of common bile duct stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy. Int. J. Surg. 2014;12(7):712–719. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valero V., III, Cosgrove D., Herman J.M., Pawlik T.M. Management of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma in the era of multimodal therapy. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;6(August 1 (4)):481–495. doi: 10.1586/egh.12.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jarnagin W.R., Blumgart L.H. Operative repair of bile duct injuries involving the hepatic duct confluence. Arch. Surg. 1999;134(July 1 (7)):769–775. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.7.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schweizer W.P., Matthews J.B., Baer H.U., Nudelmann L.I., Triller J., Halter F., Gertsch P., Blumgart L.H. Combined surgical and interventional radiological approach for complex benign biliary tract obstruction. Br. J. Surg. 1991;78(May 1 (5)):559–563. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson S.R., Koehler A., Pennington L.K., Hanto D.W. Long-term results of surgical repair of bile duct injuries following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgery. 2000;128(October 31 (4)):668–677. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.108422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lillemoe K.D., Cameron J.L. Surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: the Johns Hopkins approach. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Sci. 2000;7(April 1 (2)):115–121. doi: 10.1007/s005340050164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shanker B.A., Eng O.S., Gendel V., Nosher J., Carpizo D.R. Repair of a post-hepatectomy posterior sectoral duct injury secondary to anomalous bile duct anatomy using a novel combined surgical-interventional radiologic approach. Case Rep. Surg. 2013;12(September):2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/202315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]