Highlights

-

•

Intersphincteric proctectomy is a seldom used technique in the United States.

-

•

There is currently minimal literature on the treatment of rectal mucocele.

-

•

This technique can be applied with less morbidity than current resection technique.

Keywords: Mucocele, Intersphincteric, Proctectomy, Rectum, Anal stenosis, Case report

Abstract

In patients who have undergone a colonic resection with creation of an end colostomy, drainage of mucus secreted by the mucosa of the rectal stump may not be possible if there is an outlet obstruction. With an outlet obstruction, formation of a rectal mucocele occurs. A rectal mucocele is a rare condition which has only been reported sporadically in case reports. We present here the utility of an intersphincteric proctectomy for treatment of a rectal mucocele in a 47 year old male Crohn’s patient resulting in negligible post-operative or long-term morbidities.

1. Introduction

A mucocele is an abnormal cystic collection of mucus, which results from secretion by the lining of the mucosal epithelium within a closed space. Following operations such as a subtotal colectomy or a Hartmann’s procedure, the mucosa of the rectal stump will continue to secrete mucus that would ordinarily form mucus balls or drain via the anus periodically. However, in patients with an outlet obstruction such as severe stenosis of the anal canal, the drainage of mucus may not be possible resulting in the formation of a rectal mucocele. Luminal mucoceles have been reported in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, in patients with anal/rectal stenosis following a Hartman’s procedure, and in patients with anal or distal stoma stenosis in patients with loop colostomies [[10], [1]]. They can grow over a prolonged period of time (years), and can reach enormous sizes (1.5 l as in our case) resulting in pressure that can affect surrounding organs such as the bladder and ureters [[10], [1]]. Without the surgical removal of the mucus-producing epithelium, drainage of the rectal mucocele will only provide temporary pain resolution. Intersphincteric proctectomy for treatment of such a mucocele provides a viable surgical intervention with low documented morbidities.

2. Case history

This is the case of a 47 year-old male who presented to the emergency department with progressive, intermittent pelvic and rectal pressure, tenesmus, and intermittent urinary urgency. He had a past medical history of perianal Crohn’s disease, diagnosed at the age of fifteen years and, after a long recurrent history of non-healing perianal fistulae, was diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of the anus. After a wide local excision of the cancer and a Hartmann’s procedure with an end colostomy, the patient subsequently developed anal canal stenosis (Fig. 1). Prior to presenting to our hospital, he underwent multiple anal dilatations at a different institution. He had initially refused to undergo proctectomy with his original surgical team, expressing concerns of possible sexual dysfunction.

Fig. 1.

Computed Tomography Scan Demonstrating Perianal Fistula/Scar Tissue and Fluid Filled Rectum.

Initial examination revealed significant scarring and stenosis of the anus and anal canal. Remarkable pain was elicited on digitation using the fifth phalanx, consistent with severe stenosis, and no discernable anal sphincter complex was appreciated. A computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed fluid accumulation adjacent to the anastomotic site (Fig. 2). Examination under anesthesia was performed using a pediatric colonoscope, which revealed moderate diffuse proctitis without evidence of neoplastic disease. Random biopsies showed no evidence of dysplasia. Two Hegar dilatations were performed with successful drainage of rectal mucus; a third attempt was unsuccessful. The patient subsequently developed worsening pelvic pain and rectal pressure and was admitted.

Fig. 2.

Computed Tomography Scan Showing Tense Mucus Filled Rectum.

3. Operative course

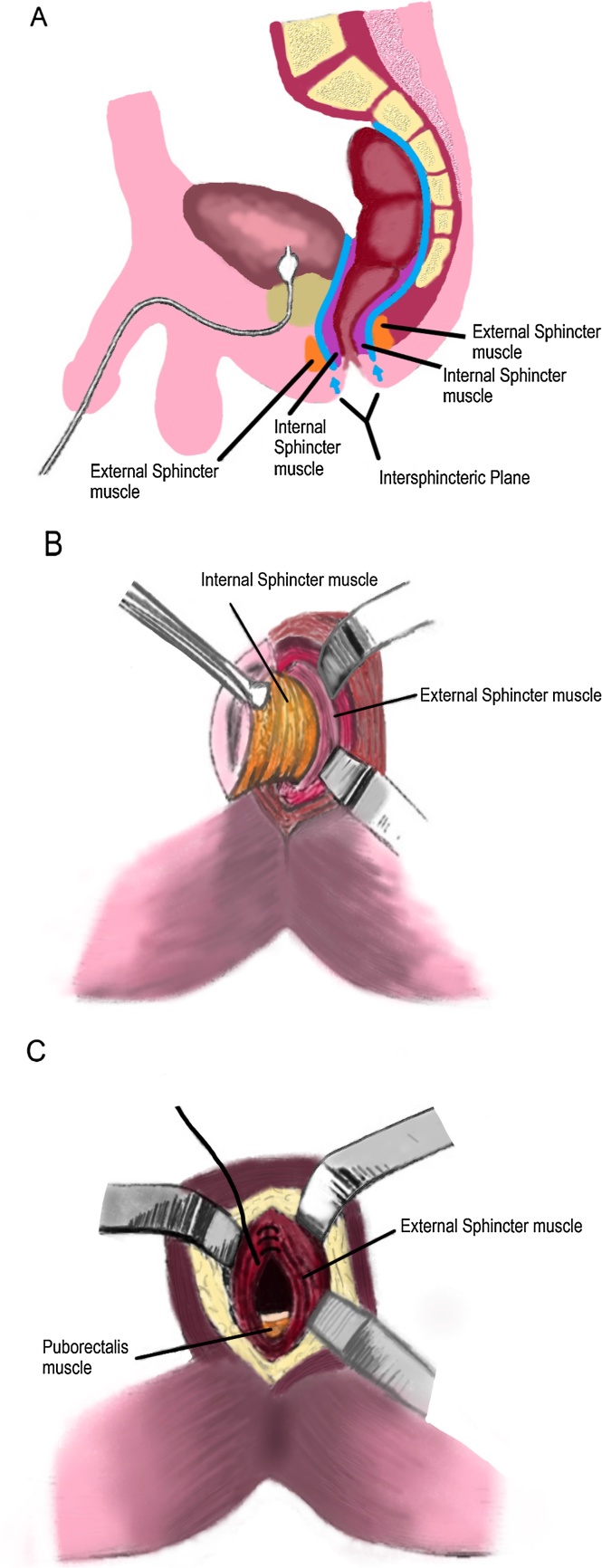

A lower midline incision was made and the abdomen was entered. Small bowel adhesions were lysed. The small bowel was carefully packed away and retracted. A distended, tense rectum was quickly encountered and 1.8 l of mucus were aspirated from the rectal stump to facilitate its excision. The rectal stump was grasped with bowel clamps and the rectum was mobilized circumferentially to the pelvic floor. We stayed very close to the rectum as total mesorectal excision was not needed here. After identification of the intersphincteric groove, safe anal canal and rectal mobilization was initiated by dissecting within the intersphincteric plane. To avoid injuries to the denonvilliers fascia, hypogastric nerves and nervi erigentes, we mobilized and dissected in close proximity to the rectum. Once a communication was evident with the abdominal cavity the dissection was completed by dividing the attachments between the external sphincter and the rectourethralis muscle. Finally, the rectum was freed and delivered through the perineum. The levator ani and external sphincter muscles were closed with interrupted sutures and the small perineal wound was closed primarily (Fig. 3a–c).

Fig. 3.

(a) Diagram of the intersphincteric Plane, Figure Adopted from Zeitels et al., 2 November 2016 [9]. (b) Mobilization of the Rectum in the Intersphincteric Plane, Figure Adopted from Zeitels et al., 2 November 2016 [9]. (c) Approximation of the External Sphincter Muscle After Intersphincteric Proctectomy, Figure Adopted from Zeitels et al., 2 November 2016 [9].

Adalimumab was withheld for four weeks. At the two-week follow-up, a minor superficial perineal wound dehiscence had fully healed. At the six-month follow-up, the patient demonstrated no indications of sexual dysfunction or recurrent rectal mucocele.

4. Discussion

The rectal mucosa is lined with glandular tissue, which continuously secretes mucus to lubricate the anal canal during defecation. Scarring, inflammation, or stenosis (benign or malignant) can result in obstruction of the anal canal, accumulation of mucus and the development of a rectal mucocele. Over time, the rectum can become significantly distended causing the patient to experience pain. Anal stenosis, a known complication of Crohn’s disease may result from chronic inflammation and fibrosis. In our patient, a wide local anodermal excision of anal cancer resulted in scarring and severe anal canal stenosis.

Although mucocele is commonly associated with other hollow organs, such as the appendix, a remnant esophagus following an esophagectomy, the craniofacial sinuses, and the gallbladder neck, rectal mucoceles are rarely reported [[1], [2], [4], [5], [7], [10]]. One such case discusses a child with an imperforate anus who had an extra-luminal pelvic mucocele following anorectal pull-through operation with incomplete mucosal excision. A mucocele was also reported in the defunctionalized colon after pull-through technique for Hirschsprung's disease. In adults, rectal mucoceles have been reported secondary to perineal, pelvic and spinal trauma [5].

Intersphincteric proctectomy was first described in 1967 by Parks, but is rarely used by surgeons in the United States. Conventional proctectomy can lead to delayed wound healing in 20–60% of patients and sexual dysfunction in 17% of patients [[9], [10]]. The operative technique of an intersphincteric proctectomy is based on the understanding that there is an embryonic plane of fusion between the rectum and anal canal and the surrounding somatic tissues. Intersphincteric dissection and primary closure of the perineal wound is associated with fewer wound complications compared with an abdominoperineal resection; the minor wound dehiscence seen in our patient was fully healed by two weeks. According to a matched pair analysis by Konanz et al., intersphincteric proctectomy is associated with significantly less sexual dysfunction compared to abdominoperineal resection (p = .0096). The study also showed that compared to low anterior resection, patients undergoing intersphincteric proctectomy also had significantly higher sexual enjoyment scores (p = .0477). It is understood that this is due to the operation involving less radical dissection in the lower pelvis placing nerves such as the pudendal nerves less at risk than in an abdominoperineal resection or low anterior resection [11]. In follow up, there was no evidence of any sexual dysfunction. His fistulas had healed and he no longer experienced pain upon sitting.

5. Conclusion

We present an interesting and unique case of rectal mucocele secondary to anal stricture. The stricture was secondary to surgical treatment of longstanding non-healing perianal fistulas and anal squamous cell carcinoma with a wide local anodermal excision. Our case sheds light on the utility and safety of the intersphincteric proctectomy technique, compared to conventional proctectomy or repeat drainage alone, in the treatment of recurring rectal mucocele.

SCARE statement

This article is compliant with SCARE criteria [12].

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Funding source

There are no sponsors and there was no special funding for writing or publication of this case report.

Ethical approval

Approval has been granted by the Clinical Research Committee.

Consent

Consent has been granted by the patient.

Author contribution

Each Author has participated in either the writing, editing, or reviewing of the paper.

Guarantor

Amajoyi, Robert C.

References

- 1.Creagh M.F., Chan T.Y.K. Case report: rectal mucocoele following Hartmann's procedure. Clin. Radiol. 1991;43(5):358–359. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)80550-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teoh A.Y.B., Lee J.F.Y., Chong C.C.N., Tang R.S.Y. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided drainage of a rectal mucocele after total colectomy for Crohn’s disease. Endoscopy. 2013;45(S 02):E252–E253. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appleton N., Day N., Walsh C. Rectal mucocoele following subtotal colectomy for colitis. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2014;96(6):e13–e14. doi: 10.1308/003588414X13946184903009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicosia J.F., Abcarian H.1. Mucocele of the distal colonic segment, a late sequela of trauma to the perineum: report of a case. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1974;17(4):536–539. doi: 10.1007/BF02587031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shivakumar S.P., Shanmugam R.P. Mucocele of the rectum. J. Clin. Case Rep. 2012:2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeitels J., Fiddian-Green R.G., Dent T. Intersphincteric proctectomy. Surgery. 1984;96(4):617–623. (Diagrams Accessed: 2 November 2016) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Witte J.T., Harms B.A. Giant colonic mucocele after diversion colostomy for ulcerative colitis. Surgery. 1989;106:571–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konanz J., Herrle F., Weiss C., Post S., Kienle P. Quality of life of patients after low anterior, intersphincteric, and abdominoperineal resection for rectal cancer—a matched-pair analysis. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2013;28(5):679–688. doi: 10.1007/s00384-013-1683-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P. The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]