Abstract

Background

This meta‐analysis was conducted to investigate the efficacy and safety of Endostar (rh‐endostatin) versus a placebo in combination with a vinorelbine plus cisplatin (NP) chemotherapy regimen for the treatment of advanced non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Methods

Two reviewers independently searched Medline, PubMed, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Embase, ASCO, ESMO, the Web of Science, and CNKI databases to locate relevant controlled clinical trials. The treatment efficacy and drug‐related toxicity of NP + Endostar (NPE) and NP groups were pooled through meta‐analysis according to random or fixed effect models.

Results

Fifteen prospective clinical studies were included in this meta‐analysis. The pooled risk ratio (RR) for objective response rate was 1.74 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.43–2.11); the objective response rate in the NPE group was significantly higher than in the NP group (P < 0.05). Nine publications evaluated the incidence of leucopenia between Endostar versus a placebo in combination with an NP chemotherapy regimen. The pooled results showed no statistically significant difference between NPE and NP chemotherapy regimens for leucopenia, thrombocytopenia, and nausea/vomiting risk (P > 0.05). The one‐year survival rate in the NPE group was higher than in the NP group, with a statistically significant difference (RR = 1.70, 95% CI 1.07–2.89; P < 0.05).

Conclusion

Endostar combined with an NP chemotherapy regimen can improve the prognosis of patients with advanced NSCLC without increasing the risk of toxicity.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, Endostar, meta‐analysis, non‐small cell lung cancer

Introduction

Because of high incidence and mortality rates, lung cancer is the leading cause of malignant carcinoma‐related death worldwide and has become a serious global problem.1 Non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which accounts for 80% of all malignant lung carcinoma cases, is usually clinically diagnosed at advanced stages, and subsequently has a poor prognosis. It has been reported that approximately 70% of NSCLC patients are diagnosed at advanced stage, and thus are ineligible for surgery.2 As such, chemotherapy, radiation, and best supportive care are generally administered to these patients; however, the prognosis is poor.

Tumor anti‐angiogenesis is one of the hotspots of current research. In 1997, Folkman et al. first reported a new protein named endostatin, a 20 kD internal fragment of the carboxy terminus of collagen XVIII.3 Endostar, a novel recombinant human endostatin expressed and purified in Escherichia coli was approved by China’s State Food and Drug Administration (SFDA) for the treatment of advanced NSCLC in 2005. Several studies have proven that the combination of Endostar with a platinum chemotherapy regimen can improve the treatment response rate.4, 5, 6 In our present meta‐analysis, we evaluate the efficacy and safety of Endostar (rh‐endostatin) versus a placebo in combination with a vinorelbine plus cisplatin (NP) chemotherapy regimen for the treatment of advanced non‐small cell lung cancer by pooling open published data in order to provide more reliable evidence.

Methods

Publication search strategy

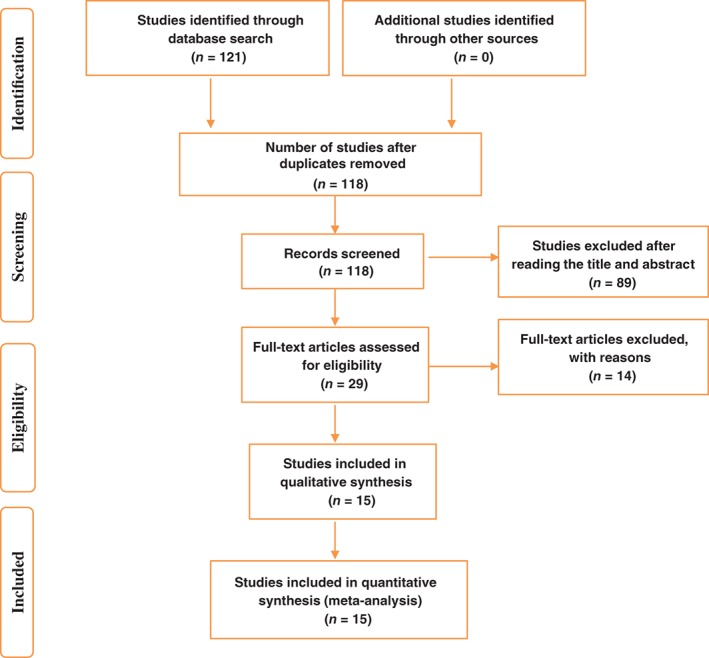

Two reviewers independently searched Medline, PubMed, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Embase, ASCO, ESMO, the Web of Science, and CNKI databases to locate relevant controlled clinical trials (Fig 1). The search items included: (i) non‐small cell lung cancer; lung cancer; lung carcinoma; NSCLC, Endostar, rh‐endostatin,YH‐16, NP chemotherapy regimen; vinorelbine, cisplatin, and chemotherapy. The search was restricted to human studies published in English or Chinese.

Inclusion criteria and data extraction

The inclusion criteria were:(i) prospective clinical trials with or without blinding; (ii) published in English or Chinese; (iii) including advanced NSCLC patients with pathological or cytological confirmation; (iv) the treatment regimens administered were NP + Endostar (NPE) and control NP chemotherapy regimen only (NP); and (v) the objective response rate (ORR), drug‐related side effects, and survival data were provided in the original studies.

General information, such as first and corresponding author names, year of publication, quality of life evaluation methods, and detailed chemotherapy regimens were extracted. The data relevant to objective response, treatment related toxicity, and survival rates were also extracted.

Statistical analysis

Stata version 12.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) was applied for data evaluation. Dichotomous data, such as complete response, partial response, and drug‐related toxicity rates were demonstrated by relative number and calculated by risk ratio (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Statistical heterogeneity across the included publications was assessed by chi‐square (χ2) test,7 and inconsistencies were calculated by I2.8 The data was pooled by fixed or random effect model according to an evaluation of statistical heterogeneity. Publication bias was assessed using Egger’s line regression text.

Results

Publication inclusion and general characteristics

Initially, 121 publications were identified from the database search; however, 106 studies were excluded because of duplication, non‐clinical studies, single arm trials, case reports or review articles, insufficient data to calculate the ORR, or published in languages other than English or Chinese. Finally, 15 prospective clinical studies were included for meta‐analysis (Fig 1).4, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 The general characteristics of the included publications are outlined in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Publication search flow chart.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the 15 included publications

| Study | No. of patients | Clinical stages | Dosage | Quality of life standard | Results | Time(year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPE/NP | ||||||

| Yang et al.9 | 54/33 | III,IV | 7.5 mg/m2, day1–14 | ECOG | ORR, adverse reaction | 2002–2003 |

| Sun et al.20 | 322/164 | III,IV | 15 mg/day, day1–14 | ECOG | ORR, adverse reaction | 2003–2004 |

| Huang et al.12 | 50/24 | III,IV | 7.5 mg/m2, day1–14 | NR | ORR | 2005 |

| Huang10 | 20/20 | III,IV | 15 mg/day, day1–14 | KPS | ORR, survival, adverse reaction | 2006–2007 |

| Fan et al.13 | 20/20 | III,IV | 7.5 mg/m2, day1–14 | KPS | ORR, adverse reaction | 2006–2007 |

| Cai et al.11 | 39/32 | III,IV | 15 mg/day, day1–14 | KPS | ORR, survival, adverse reaction | 2006–2007 |

| Wen et al.9 | 43/41 | Advanced | 7.5 mg/m2, day1–14 | KPS | ORR, adverse reaction | 2007–2010 |

| Yang et al.14 | 13/18 | IIIb,IV | 15 mg/day, day1–14 | KPS | ORR, adverse reaction | 2006–2008 |

| Wang et al.15 | 17/18 | IIIb,IV | 7.5 mg/m2, day1–14 | ECOG | ORR, survival, adverse reaction | NR |

| Yang4 | 60/38 | III,IV | 15 mg/day, day1–14 | NR | ORR, adverse reaction | 2008–2012 |

| Liu et al.5 | 38/34 | III,IV | 7.5 mg/m2, day1–14 | ECOG | ORR, survival | 2007–2009 |

| Zhang et al.6 | 20/8 | III,IV | 7.5 mg/m2, day1–14 | ECOG | ORR, survival | 2009 |

| Wang et al.16 | 14/17 | IIIb,IV | 15 mg/day, day1–14 | ECOG | ORR, survival, adverse reaction | 2007–2008 |

| Guet al.17 | 26/26 | IIIb,IV | 7.5 mg/m2, day1–14 | ECOG | ORR, survival, adverse reaction | 2005–2008 |

| Guo & Hu18 | 16/30 | IIIb,IV | 15 mg/day, day1–14 | KPS | ORR, adverse reaction | 2006–2009 |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; KFS, Karnovsky Performance Status; ORR, objective response rate; NP, vinorelbine plus cisplatin; NPE Endostatin + NP; NR, not reported.

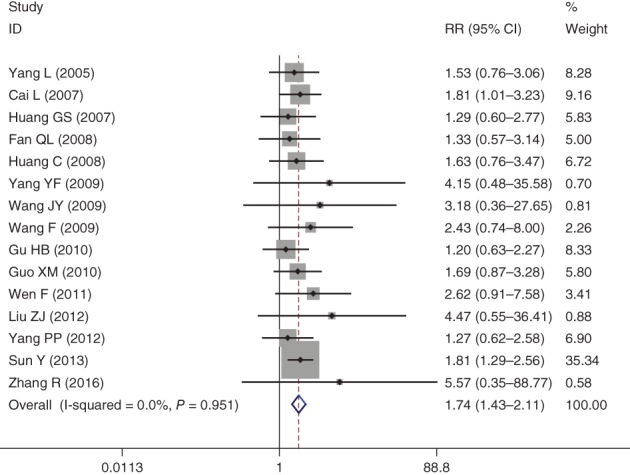

Clinical efficacy

Fifteen studies reported the ORR. The fixed effect model was applied and revealed no significant heterogeneity across the 15 included publications (I2 = 0.0; P = 0.95). The pooled risk ratio (RR) for ORR was 1.74 (95% CI 1.43–2.11), indicating that the ORR in the NPE group was significantly higher than in the NP group (P < 0.05) (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of objective response rate for Endostar versus placebo in combination with vinorelbine plus cisplatin chemotherapy regimen in treatment of advanced non‐small cell lung cancer. CI, confidence interval.

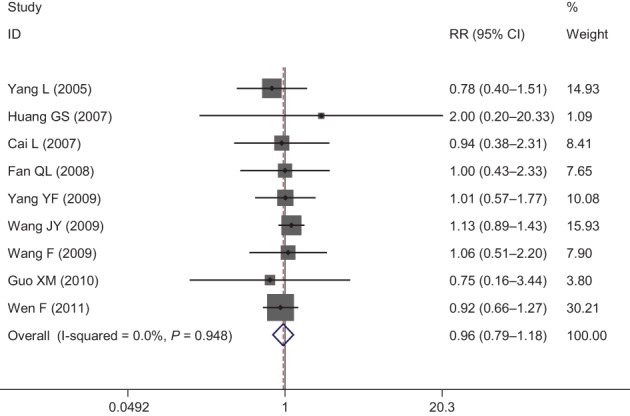

Leukopenia

Nine publications evaluated the leucopenia incidence rate between the groups for the treatment of advanced NSCLC. The pooled results showed that there was no statistical difference in leucopenia risk between NPE and NP groups (RR = 0.96, 95% CI 0.79–1.18; P > 0.05) (Fig 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of leukopenia for Endostar versus placebo in combination with vinorelbine plus cisplatin chemotherapy regimen in treatment of advanced non‐small cell lung cancer. CI, confidence interval.

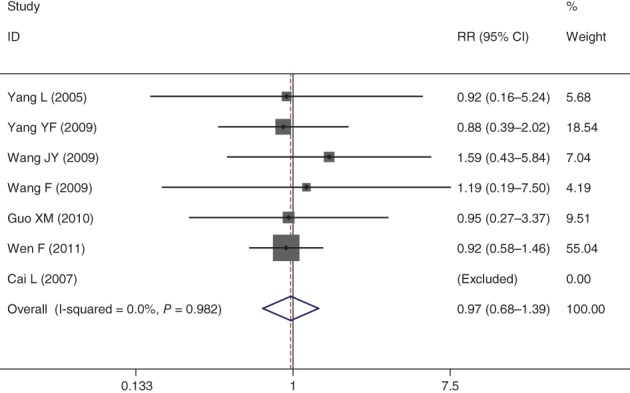

Thrombocytopenia

Of the included 12 studies, 6 publications reported the thrombocytopenia risk of Endostar versus a placebo in combination with an NP chemotherapy regimen for the treatment of advanced NSCLC. Heterogeneity across the included studies was not significant. Therefore, the combined risk of thrombocytopenia between NPE and NP regimens was pooled using a fixed effect model. The results demonstrated that adding Endostar to the combined NP chemotherapy regimen did not increase the risk of developing thrombocytopenia (RR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.68–1.39; P > 0.05) (Fig 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of thrombocytopenia for Endostar versus placebo in combination with vinorelbine plus cisplatin chemotherapy regimen in treatment of advanced non‐small cell lung cancer. CI, confidence interval.

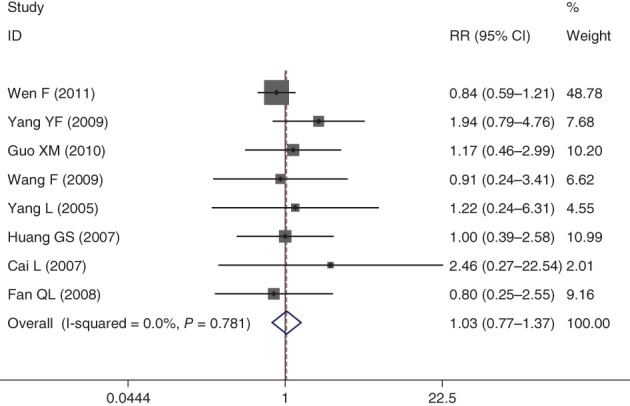

Nausea and vomiting

Eight publications evaluated the nausea and vomiting incidence rate between the NPE and NP groups. For non‐statistical heterogeneity, the data was pooled using a fixed effect model. The combined results indicated that Endostar combined with an NP chemotherapy regimen did not increase the risk of nausea and vomiting compared to the NP regimen (RR = 1.03, 95% CI 0.77–1.37; P < 0.05) (Fig 5).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of nausea and vomiting for Endostar versus placebo in combination with vinorelbine plus cisplatin chemotherapy regimen in treatment of advanced non‐small cell lung cancer. CI, confidence interval.

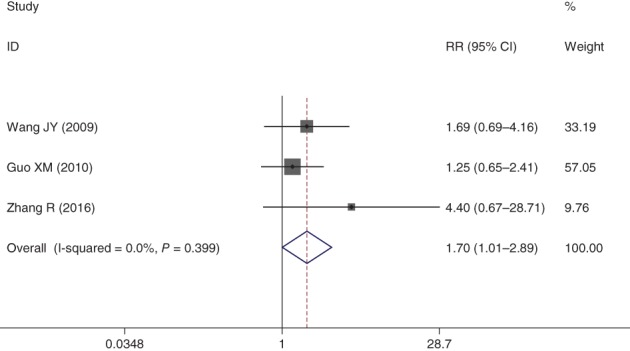

One‐year survival

Three studies reported the one‐year survival rate of NPE and NP chemotherapy regimens. The pooled studies showed that one‐year survival was higher in the NPE group than in the NP group, and the difference was statistically significant (RR = 1.70, 95% CI 1.07–2.89; P < 0.05) (Fig 6).

Figure 6.

Forest plot of one‐year survival rate for Endostar versus placebo in combination with vinorelbine plus cisplatin chemotherapy regimen in treatment of advanced non‐small cell lung cancer. CI, confidence interval.

Publication bias

Publication bias in regard to clinical efficacy, leucopenia, thrombocytopenia, nausea/vomiting, and one‐year survival rate were assessed using Egger’s line regression test. The results demonstrated no significant publication bias for clinical efficacy (P > 0.05), leucopenia (P > 0.05), thrombocytopenia (P > 0.05), or nausea/vomiting (P > 0.05). However, significant publication bias existed in regard to one‐year survival rates (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Publication bias evaluation using Egger’s line regression test

| Items | Coefficient | SE | t | P | 95% CI of coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical efficacy | 0.64 | 0.34 | 1.89 | 0.08 | 0.02–0.58 |

| Leukopenia | −0.24 | 0.33 | −0.72 | 0.50 | −1.01–0.55 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0.38 | 0.30 | 1.23 | 0.29 | −0.47–1.21 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 0.78 | 0.44 | 1.77 | 0.13 | −0.30–1.85 |

| One‐year survival | 2.05 | 0.15 | 13.33 | 0.04 | 0.09–4.00 |

CI, confidence interval; SE, standard error.

Discussion

Platinum‐based chemotherapy is currently considered the first‐line treatment regimen for advanced NSCLC patients.21, 22, 23 Efficacy and long‐term survival rates in patients treated with a combined chemotherapy regimen are greater than in those administered a non‐platinum chemotherapy regimen; however, the difference according to previously published prospective randomized clinical trials and high quality meta‐analysis was not statistically significant.23, 24

The rapid development of tumor‐targeted drugs has led to the use of some molecular targeting drugs in the clinical treatment of NSCLC. The combination of conventional chemotherapy regimens with tumor targeting drugs has become one of the hotspots of clinical research. Endostar is a novel artificially synthesized anti‐angiogenesis drug, approved by the SFDA for clinical use for the treatment of advanced NSCLC. Recently, several open published prospective clinical trials have evaluated the short‐term efficacy and long‐term survival of platinum‐based chemotherapy plus Endostar regimens for the treatment of advanced NSCLC. Sun et al. reported long‐term results of a randomized, double blind, placebo‐controlled phase III trial of Endostar versus a placebo in combination with vinorelbine and cisplatin for advanced NSCLC.20 In this clinical trial, the authors recruited 486 NSCLC patients and randomly divided them into NP plus Endostar and NP plus placebo groups. Patients were treated every third week for two to six cycles. The authors found that the addition of Endostar to an NP regimen significantly improved the survival of advanced NSCLC patients, compared to an NP chemotherapy regimen alone. However, Huang did not report any benefit in the ORR using Endostar combined with an NP chemotherapy regimen for the treatment of advanced NSCLC.10

We included 15 prospective clinical studies in our meta‐analysis and found that Endostar combined with NP significantly improved ORRs and one‐year survival, but did not increase the risk of leucopenia, thrombocytopenia, and nausea/vomiting. These results indicated that advanced NSCLC patients might benefit from a clinical treatment regimen of Endostar combined with NP chemotherapy. However, our results were based on published randomized controlled trials and not on individual patient data, thus meta‐analysis of individual data was not performed. Secondly, most studies did not report long‐term survival data; therefore, the long‐term efficacy of Endostar combined with an NP chemotherapy regimen requires further evaluation using high quality randomized controlled trials. Thirdly, most of the studies included in this meta‐analysis were performed in a Chinese Han population, which may lead to patient selection bias.

Considering these limitations, our conclusions should be interpreted with caution and require further evidence from well‐designed multicenter prospective randomized clinical trials.

Disclosure

No authors report any conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67: 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD et al Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2016; 66: 115–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Reilly MS, Boehm T, Shing Y et al Endostatin: An endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cell 1997; 88: 277–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yang PP. [Combined with the third generation platinum (NP) for the treatment of advanced non‐small cell lung cancer.] China Pract Med 2012; 7: 3–4 (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu ZJ, Wang J, Wei XY et al Predictive value of circulating endothelial cells for efficacy of chemotherapy with Rh‐endostatin in non‐small cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2012; 138: 927–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang R, Wang ZY, Li YH et al Usefulness of dynamic contrast‐enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for predicting treatment response to vinorelbine‐cisplatin with or without recombinant human endostatin in bone metastasis of non‐small cell lung cancer. Am J Cancer Res 2016; 6: 2890–900. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986; 7: 177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003; 327: 557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang L, Wang JW, Cui CX et al [Rh‐endostatin (YH‐16) in combination with vinorelbine and cisplatin for advanced non‐small cell lung cancer: A multicenter phase II trial.] Chin J New Drugs 2005; 14: 204–7 (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huang GS. [The efficacy of NP plus ENDOSTAR and chemotherapy in the treatment of non‐small cell lung cancer.] Henan J Surg 2007; 13: 1–2 (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cai L, Sun LC, Yang CY, Meng QW, Pang H, Sui GJ. [Endostar combined with chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced non‐small cell lung cancer.] Chin J Pract Intern Med 2007; 27: 1541–2 (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang C, Wang LC, Xiao JY et al [Analysis of cavitation of advanced NSCLC treated by rh‐endostatin combined with NIP chemotherapy.] Chin J Oncol 2008; 30: 712–5 (In Chinese.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fan QL, Kao J, Zhou WL. [The short‐term efficacy of recombinant human endostatin injection combined with NP regimen in the treatment of advanced non‐small cell lung cancer.] Mod J Integr Tradit Chin West Med 2008; 17: 1170–1 (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang YF. [Short‐term efficacy of Endostar combined with NP regimen in the treatment of advanced non‐small cell lung cancer.] Mod J Integr Tradit Chin West Med 2009; 18: 421–2 (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang JY, Cai Y. A randomized clinical trial of NVB plus DDP with Rh‐endostatin in the treatment of advanced retreated non‐small‐cell lung cancer. J Clin Med Pract 2009; 13: 34–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang F, Wang YF, Yang L. [Therapeutic effect of recombinant human angioendostatin combined with NP regimen in the treatment of advanced non‐small cell lung cancer.] J Pract Med 2009; 25: 3121–2 (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gu HB, Zhu YF, Tan QH, Lu JG. [The clinical observation of advanced NSCLC treated by recombinant human endostatin in combination with NP regimen.] J Basic Clin Oncol 2010; 2010: 54–5 (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guo XM, Hu T. [Therapeutic effect of recombinant human endostatin combined with NP chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced non‐small cell lung cancer in the elderly patients.] Chin J Clin Rational Drug Use 2010; 3: 69–70 (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wen F, Wang W, Shang LQ et al [Short‐term effects of Endostar combined with NP regimen for non‐small cell lung cancer.] J Clin Med Pract 2011; 15: 79–80 (In Chinese.) [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sun Y, Wang JW, Liu YY et al Long‐term results of a randomized, double‐blind, and placebo‐controlled phase III trial: Endostar (rh‐endostatin) versus placebo in combination with vinorelbine and cisplatin in advanced non‐small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer 2013; 4: 440–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Inno A, Di Noia V, D'Argento E, Modena A, Gori S. State of the art of chemotherapy for the treatment of central nervous system metastases from non‐small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2016; 5: 599–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Santos FN, Castria TB, Cruz MR, Riera R. Chemotherapy for advanced non‐small cell lung cancer in the elderly population. Sao Paulo Med J 2016; 134: 465–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dietrich MF, Gerber DE. Chemotherapy for advanced non‐small cell lung cancer. Cancer Treat Res 2016; 170: 119–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. NSCLC Meta‐analysis Collaborative Group . Preoperative chemotherapy for non‐small‐cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2014; 383: 1561–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]