Abstract

Introduction

Family relationships, social connectedness and a greater network of supportive others each predict better drinking outcomes among individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD). The association between social factors and drinking may be related to the ability of individuals to take the perspectives of others’ mental and emotional states, defined as empathic processing (EP). As such, it may be the case that EP is associated with social support (SS) and drinking behavior among individuals with AUD, yet few prior studies have attempted to define EP in an AUD sample.

Methods

The current study was a secondary data analysis of Project MATCH (N=1,726) using structural equation modeling to model EP as a latent factor. The study also sought to test the baseline associations between EP, SS, and drinking behavior, as well as sex differences in the associations between EP, SS, and drinking. It was hypothesized that EP would be positively associated with SS and negatively associated with drinking behavior.

Results

Results suggested adequate model fit of the EP construct. Structural equation models indicated significant associations between EP, SS, and both drinking consequences and percent drinking days, but only for males. Males reported significantly lower EP and SS from friends, but more SS from family, compared to females. EP was not related to drinking among females.

Conclusions

The current study validated a model of EP in a treatment-seeking sample of individuals with alcohol use disorder. Future work may consider EP as a treatment-modifiable risk factor for drinking frequency and consequences in males.

Keywords: Empathy, Alcohol Use Disorder, Social Support, Project MATCH, Sex Differences

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Support, Empathy, and Drinking

Drinking-related social consequences and transitional life events (e.g., divorce due to alcohol use) are associated with attempts to reduce drinking (Dawson et al., 2006). This behavior may be related to the capacity of the individual to internalize the feelings and perspectives of others regarding drinking-related consequences. While there are a number of different definitions for the various aspects of internally modeling either the thoughts or feelings of others and responding accordingly (e.g., empathy, theory of mind, perspective taking, etc.), we propose the overarching term “empathic processing” (EP) to operationally define the various permutations of representing the experiences of others within the self. We further propose that EP may play a role in drinking changes among heavy drinkers, and lack of EP ability may explain continued heavy drinking despite social consequences. In line with this, Dearing and colleagues (2013) found that guilt (an “other-centric” emotion) is more predictive of drinking reduction among non-treatment seeking heavy drinkers than shame (a “self-centric” emotion). Likewise, among treatment seekers there is evidence that other-centric considerations are important for following treatment recommendations (Ryan et al., 1995).

Despite the possible role EP might play in treatment seeking, most individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD) do not actually perceive a need for treatment (Hedden & Gfroerer, 2011) and often do not consider seeking treatment until after social relationships are damaged (Tucker et al., 1995; 2004). The role of social support (SS) and environmental factors in the change (or persistence) of drinking is well documented in the alcohol treatment literature (McCrady, 2004; Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2004). Protective factors such as spousal commitments and family tend to be helpful in the maintenance of non-problem drinking (Tucker, 2004) and retention in alcohol treatment (Simpson & Joe, 1993). Even support unspecific to drinking predicts a higher number of percent days abstinent following treatment (Beattie & Longabaugh, 1999).

There is a small, but growing body of literature examining constructs related to EP and their associations with heavy drinking. For example, Maurage and colleagues (2011) found that heavy drinkers had a deficit in the emotional understanding of the feelings of others, which was replicated by Ferrari et al. (2014) using similar measures. Likewise, Bosco and colleagues (2014) found general deficits among drinkers on self-reported ability to understand both the feelings and mental states of others. Numerous other studies report emotion recognition dysfunction in alcohol samples as well (Philippot et al., 1999; Uzun, 2003; Uerkermann et al., 2005).

Studies have found that individuals with AUD show not only a decreased recognition of emotional content in general, but also a bias toward identification of negative affect and anger in particular, over-attributing anger to both emotional and non-emotional stimuli (Frigerio et al., 2002; Maurage et al., 2009; Dethier & Blairy, 2012). This may signal either a predisposition for or the development of lower levels of EP among individuals with AUD. This replicated finding has real-world implications for how EP might be disrupted in heavy drinkers, contributing to potentially greater alcohol use whereby drinkers’ sensitivity to negative and threatening cues might perpetuate behaviors or affective experiences that lead to further alcohol use. Indeed, research has suggested a potential cyclical problem whereby drinking infringes upon healthy emotional behavior, which in turn drives social consequences and potentially more drinking behavior (Philippot et al., 1999).

Although EP is often considered an individual-level trait, trait-level EP may be interconnected with external social factors and levels of SS, which each show correlations with drinking reduction. Specifically, individuals with lower levels of EP might have difficulty in maintaining social relationships and might demonstrate deficits in other social behaviors (e.g., interpersonal conflict, acting with aggression; Davis, 2004). Within romantic relationships, individual differences in EP are associated with relationship support, above and beyond other relational variables (Devoldre, Davis, Verhofstadt, & Buysse, 2010). Furthermore, as reviewed above, there is an established relationship between efforts to reduce drinking and social factors that support reductions in drinking. Given the observed associations between EP and SS and associations between SS and drinking, we controlled for the perceived availability of social support in our analysis of EP and drinking, as described below.

1.2. Sex Differences in AUD and EP

The importance of examining sex differences in health-related research has been highlighted since 1993, when the National Institutes of Health in the United States introduced the stipulation that women should be included in clinical trials. More recently, the Sex and Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) guidelines have recommended that sex and gender information be reported in all research (Heidari et al., 2016). Sex differences are critical to examine in the field of addiction given widespread underrepresentation of women in the literature yet known sex differences in animal and human models of addiction (Becker et al., 2017; Wetherington, 2007). In AUD, females tend to progress from initial drinking to AUD and treatment seeking more quickly than males (Zilberman et al., 2003), although this trend is changing as more females are drinking hazardously and becoming dependent on alcohol at the same rates as males (Keyes, et al., 2010). Sex differences on empathy are mixed in the literature. Research using a large, population-based sample, found higher self-reported empathy in women, but few sex differences emerged in an experimental paradigm (Baez et al., 2017). No studies have examined sex differences on EP in AUD samples although a recent review called for more research on the role of sex in the association between empathy and substance use disorders (Massey et al., 2017).

1.3. Current Study

Potential relationships between drinking and EP ability exist in prior studies (Bosco et al., 2014; Maurage et al., 2011), but the role of EP on specific drinking variables has not been thoroughly investigated and prior research has not considered EP uniquely from the effects of SS. The present analysis sought to test a model of EP and SS in a large sample of treatment-seeking AUD patients. The current study extends the limited literature on EP by examining the construct in a large sample of individuals with AUD. This is significant in that most studies showing EP deficits in AUD have typically relied on smaller, more severe, and often inpatient samples (Maurage et al., 2009; Dethier & Blairy, 2012; Kornreich et al., 2013). Also, given that the role of social factors in drinking is well known (McCrady, 2004; Tucker, 2004), we sought to study whether EP is associated with drinking behavior after controlling for the effects of perceived SS. These results will help characterize the utility of an original model of the relationship among EP, SS, and drinking. Further, we sought to explore whether there were sex differences in the relationship among EP, SS, and drinking behavior.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

The current study is a secondary data analysis of Project MATCH (Matching Alcoholism Treatments to Client Heterogeneity; Project MATCH Research Group, 1997). Participants (N=1,726; 75.7% male) were recruited from nine clinical research sites (controlled for in our analyses), divided into outpatient and aftercare “arms.” The outpatient arm (n=952, 72% male) included patients recruited from the community for outpatient treatment for AUD. The aftercare arm (n=774, 80% male) consisted of individuals recruited from inpatient or intensive day hospital treatment. Both arms used identical methods including randomization to one of three treatment conditions: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET), or Twelve-Step Facilitation (TSF). Although the original study was a longitudinal treatment study, this analysis concerns only baseline data prior to any treatment sessions.

2.2. Measures

The present study tested a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of 17 psychosocial items as indicators of an empathic processing (EP) latent factor and two latent social support (SS) factors, SS from friends and SS from family, as correlated with baseline drinking levels. The EP model consisted of 5 items from the Personal Attributes Questionnaire (PAQ; Spence et al., 1974), 1 item from the California Psychological Inventory (CPI; Gough, 1994), and 1 item from the Interpersonal Dependency Inventory (IDI; Hirschfeld et al., 1997; Bornstein, 1997). The measurement models for SS-friends and SS-family were evaluated using 8 items taken from the Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ; Procidano & Heller, 1983). A list of items and related instruments is included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Items, Item ID Codes, and Related Instruments

| Item ID | Description |

|---|---|

| IDI Q9 | “I am willing to disregard other people’s feelings in order to accomplish something that’s important to me.” (Not like me 1, 2, 3, 4 Very like me) |

| CPI Q21 | “I often think about how I look and what impression I am making upon others” (T/F) |

| PAQ Q7 | “Not at all able to devote self completely to others 1…2…3…4…5 Able to devote self completely to others.” |

| PAQ Q9 | “Not at all helpful to others 1…2…3…4…5 Very helpful to others.” |

| PAQ Q12 | “Not at all kind 1…2…3…4…5 Very kind.” |

| PAQ Q15 | “Not at all aware of feelings of others 1…2…3…4…5 Very aware of feelings of others.” |

| SS1 Q1 | “My friends give me the moral support I need” 0=No, 1=Yes, 9=Don’t Know |

| SS1 Q3 | “I rely on my friends for emotional support” 0=No, 1=Yes, 9=Don’t Know |

| SS1 Q5 | “My friends are sensitive to my personal needs” 0=No, 1=Yes, 9=Don’t Know |

| SS1 Q6 | “My friends are good at helping me solve problems” 0=No, 1=Yes, 9=Don’t Know |

| SS2 Q1 | “My family gives me the moral support I need” 0=No, 1=Yes, 9=Don’t Know |

| SS2 Q3 | “I rely on my family for emotional support” 0=No, 1=Yes, 9=Don’t Know |

| SS2 Q5 | “My family is sensitive to my personal needs” 0=No, 1=Yes, 9=Don’t Know |

| SS2 Q6 | “My family is good at helping me solve problems” 0=No, 1=Yes, 9=Don’t Know |

| DrInC | Total drinking consequences at baseline |

| Form 90 | Percent drinking days at baseline |

| Form 90 | Percent heavy drinking days at baseline |

| Form 90 | Number of drinks per drinking day at baseline |

For the EP construct, we selected indicators resembling items on the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI; Davis, 1983), the most widely used self-report measure of EP. Because Project MATCH did not explicitly measure EP as a construct, we approximated a measure of EP using items across measures that were collected in Project MATCH using them to estimate a latent factor of EP in the current analyses. Specifically, if an item used in Project MATCH was viewed as similar in meaning to an item in the IRI, it was considered for inclusion in the CFA and later trimmed if correlation residuals indicated a potential source of misfit and/or standardized loadings were minimal. All of the surviving items were subsequently re-compared qualitatively with items on the IRI. Descriptions of the original measures from Project MATCH that were used to identify indicators of EP follow.

2.2.1. Demographics

A single item was used to measure participant “sex” with response choices of female (sex=0) and male (sex=1). Gender identity was not assessed.

2.2.2. Personal Attributes Questionnaire (PAQ)

The PAQ was originally designed to measure stereotypical masculine and feminine traits but was repurposed here for the items indicative of EP (Table 1). Participants endorse on a 1–5 scale how strongly a given item relates to them. The reliability of the five PAQ items in the current sample was α=0.75.

2.2.3. California Psychological Inventory Socialization Scale (CPI)

The CPI measures personality traits such as “dominance” and “self-control”. We used as one item from the CPI as an indicator of empathic processing: “I often think about how I look and what impression I am making upon others.”

2.2.4. Interpersonal Dependency Inventory (IDI)

The IDI measures “dependency” social behaviors such as emotional attachment to others. We used a single item from the IDI for its implications in EP: “I am willing to disregard other people’s feelings in order to accomplish something that’s important to me.”

2.2.5. Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ)

The eight items of the SSQ (Procidano & Heller, 1983) were used to represent social support from family (SS-family) and social support from friends (SS-friends). SS-friends items had reliability of α=0.85 and SS-family items had reliability at α=0.84.

2.2.6. Drinking Measures

Drinking measures were taken from the Form-90, a clinical interview in which participants recall their daily drinking retrospectively for the prior 90 days (Miller & Del Boca, 1994). Baseline measures of number of drinks per drinking day, percent drinking days, and percent heavy drinking days were included in the full structural model, described below. We also examined the association between EP, SS, and total drinking consequences at baseline as measured by the Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC; Miller et al., 1995). The reliability of the DrInC in the current sample was α=0.94.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

We used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA; Kline, 2011) to examine item-level latent factors for EP, SS-friends, and SS-family in a measurement model and then estimated the association between these latent factors and drinking measures (from the Form-90 and DrInC) in a structural equation model (SEM). All variables were assessed for normality, outliers, missing data, and collinearity before being included in the CFA, with only slight skew for the items from the CPI and IDI. Data were missing for fewer than 2% of items.

Items from the above scales were estimated to load on the EP and SS latent factors using unit-loading identification. CFA and SEM were conducted in Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2015) using the variance-covariance matrix, listing all indicators as categorical, and assessing correlation residuals for targets of measurement model misfit before re-specification. In all models, we used a robust weighted least squares estimator with delta parameterization (WLSMV), an appropriate estimation method given categorical indicators (Li, 2016). To assess model fit we looked for a non-significant χ2 (p≥0.05), a Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1993) below 0.05, and a Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990) above 0.95. Correlations, sample sizes, and descriptive statistics are in Tables 2a and 2b. The final SEM included treatment arm (outpatient versus aftercare) and sex as covariates. We also tested measurement invariance of the EP latent factor by sex and estimated the final model within males and females separately.

Table 2.

| a. Empathic Processing—Descriptives and Correlations Per Item

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDI Q9 | CPI Q21 | PAQ Q7 | PAQ Q9 | PAQ Q12 | PAQ Q15 | |

|

|

||||||

| IDI Q9 | 1 | |||||

| CPI Q21 | −0.03 | 1 | ||||

| PAQ Q7 | −0.16** | 0.01 | 1 | |||

| PAQ Q9 | −0.17** | 0.01 | 0.36** | 1 | ||

| PAQ Q12 | −0.23** | 0.05* | 0.27** | 0.45** | 1 | |

| PAQ Q15 | −0.33** | 0.09** | 0.27** | 0.34** | 0.46** | 1 |

|

| ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.59 (0.86) | 0.79 (0.4) | 3.28 (1.07) | 4.15 (0.82) | 4.23 (0.77) | 4.00 (0.90) |

| N | 1697 | 1725 | 1697 | 1696 | 1696 | 1689 |

| %Missing | 1.7 | 0.1 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 2.1 |

| b. Social Support—Descriptives and Correlations Per Item

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS1 Q1 | SS1 Q3 | SS1 Q5 | SS1 Q6 | SS2 Q1 | SS2 Q3 | SS2 Q5 | SS2 Q6 | |

|

|

||||||||

| SS1 Q1 | 1 | |||||||

| SS1 Q3 | 0.42** | 1 | ||||||

| SS1 Q5 | 0.61** | 0.56** | 1 | |||||

| SS1 Q6 | 0.56** | 0.51** | 0.62** | 1 | ||||

| SS2 Q1 | 0.21** | 0.04 | 0.17** | 0.12** | 1 | |||

| SS2 Q3 | 0.12** | 0.17** | 0.16** | 0.11** | 0.48** | 1 | ||

| SS2 Q5 | 0.20** | 0.09** | 0.28** | 0.17** | 0.64** | 0.53** | 1 | |

| SS2 Q6 | 0.14** | 0.10** | 0.19** | 0.22** | 0.54** | 0.56** | 0.61** | 1 |

|

| ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.72 (0.45) | 0.42 (0.49) | 0.55 (0.50) | 0.53 (0.50) | 0.79 (0.41) | 0.57 (0.50) | 0.64 (0.48) | 0.57 (0.50) |

| N | 1457 | 1579 | 1330 | 1455 | 1548 | 1588 | 1465 | 1515 |

| %Missing | 15.6 | 8.5 | 22.9 | 15.7 | 10.3 | 8.0 | 15.1 | 12.2 |

Correlation is significant at p<0.01 level;

Correlation is significant at p<0.05 level

3. Results

3.1. Measurement Models

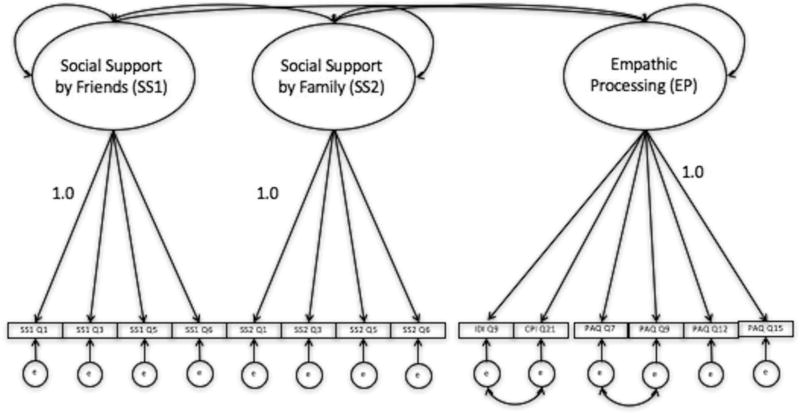

Results from the CFA for EP had a significant χ2 test (χ2 (14)=101.96, p<0.001) but acceptable model fit based on the RMSEA=0.06 (90% CI 0.05, 0.07), and CFI=0.97. Adding latent factors for SS-family and SS-friends to the CFA improved model fit on the CFI=0.99 and RMSEA=0.03 (90% CI 0.02, 0.03), with a significant χ2 test (χ2 (87)=193.24, p<0.001). The full set of factor loadings for this model are shown in Table 3. All factor loadings were significant for the EP latent factor (all p<0.01). When testing for invariance between males and females on EP, partial metric invariance was met whereby the same model structure and factor loadings held for both groups except for item IDI Q9, which represents antisociality in the EP construct (see Table 1 & Figure 1). This item loaded more strongly for males (B(SE)=−0.55 (0.05); p<0.001) than females (B(SE)=−0.23 (0.07); p=0.002).

Table 3.

Unstandardized and Standardized Factor Loadings for CFA Measurement Models

| EP Latent Factor | SS-Friends Latent Factor | SS-Family Latent Factor | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | B (SE) | β | Item | B (SE) | β | Item | B (SE) | β |

| PAQ Q15 | 1.00(0.00) | 0.70 | SS1 Q1 | 1.00(0.00) | 0.88 | SS2 Q1 | 1.00(0.00) | 0.92 |

| CPI Q21 | −0.11(0.06) | −0.07 | SS1 Q3 | 0.91(0.03)*** | 0.80 | SS2 Q3 | 0.90(0.02)*** | 0.83 |

| IDI Q9 | −0.69(0.04)*** | −0.48 | SS1 Q5 | 1.01(0.03)*** | 0.96 | SS2 Q5 | 1.01(0.02)*** | 0.94 |

| PAQ Q7 | 0.69(0.03)*** | 0.48 | SS1 Q6 | 1.00(0.02)*** | 0.88 | SS2 Q6 | 0.97(0.02)*** | 0.89 |

| PAQ Q9 | 0.94(0.02)*** | 0.66 | ||||||

| PAQ Q12 | 1.09(0.03)*** | 0.76 | ||||||

Note. *** Parameter estimate is significant at p<0.001 level;

Parameter estimate is significant at p<0.01 level;

Parameter estimate is significant at p<0.05 level; Confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) for latent SS-Friends and SS-Family were estimated simultaneously in the same model

Figure 1.

Confimatory Factor Model (i.e., Measurement Model) of EP and SS-Friends and SS-Family

The SS latent factors, separated into SS-family and SS-friends, also had significant loadings (all β>0.4, p<0.001) and were significantly correlated (r=0.31, p<0.001). EP was more strongly related to SS-friends (r=0.34) than SS-family (r=0.13), but both relationships were significant (p<0.001), indicating a significant association between EP and SS. Invariance testing between sexes showed that the same set of relationships and loadings held for males and females except for item SS1 Q6 (see Table 1 & Figure 1), meeting partial metric invariance. This item represents the utility of seeking SS-friends in times of need and was a significant loading for females (B(SE)=0.97 (0.04); p<0.001), but not males (B(SE)=1.89 (2.17); p=0.39).

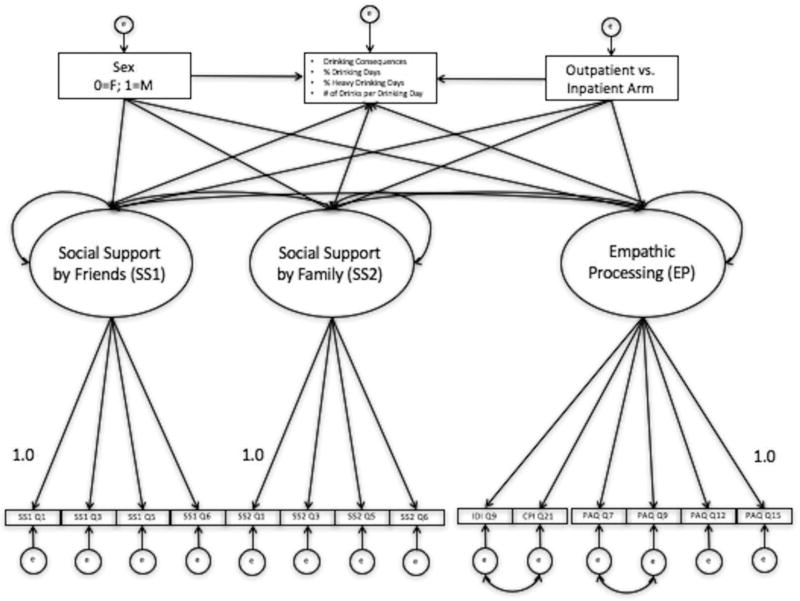

3.2. Structural Models

Next, we estimated a structural model shown in Figure 2, with the latent EP, SS-family, and SS-friends factors as predictors of drinking variables controlling for treatment arm and participant sex. Dependent variables of interest included observed drinking intensity (drinks per drinking day), frequency (percent drinking days and percent heavy drinking days), and drinking consequences at baseline. A model that included all drinking variables simultaneously would not converge, likely due to high collinearity; therefore the SEM was used to predict the drinking variables separately.

Figure 2.

Structural model of EP, SS, and Drinking Variables

The SEM predicting total drinking consequences had a significant χ2 (χ2 (105)=375.13, p<0.001), but adequate fit on the CFI=0.98, and RMSEA=0.04 (90% CI: 0.034, 0.043). The models of drinking intensity and frequency also provided adequate fit on the CFI and RMSEA (percent drinking days: χ2 (105)=316.07, p< 0.001, CFI=0.99, and RMSEA=0.03; 90% CI: 0.030, 0.038; percent heavy drinking days χ2 (105)=317.15, p<0.001, CFI=0.99, and RMSEA=0.022; 90% CI: 0.017, 0.027; drinks per drinking day: χ2 (114)=212.42, p<0.001, CFI=0.99, and RMSEA=0.03; 90% CI: 0.030, 0.039).

In the model controlling for sex (Table 4, block 1), EP was significantly, negatively associated with total drinking consequences. EP was not significantly associated with any of the other drinking variables in these models. SS-family and SS-friends were each significantly negatively associated with drinking consequences and total drinks per drinking day, but were not associated with frequency of drinking. EP and SS-family/SS-friends were significantly, positively associated in these models. Treatment arm was also significantly associated with drinking variables, with aftercare participants reporting higher baseline frequency of heavy drinking, greater number of drinks per drinking day, and total drinking consequences. Being male (vs. female) in this sample significantly predicted lower EP (β=−0.23; B(SE)=−0.38 (0.05); p<0.001). Additionally, being male was associated with decreased SS-friends (β=−0.13; B(SE)=−0.26 (0.06); p<0.001) and higher SS-family (β=0.14; B(SE)=0.30 (0.07), p<0.001).

Table 4.

Structural Models Controlling for Sex—Predictive Associations Between Latent EP, SS, & Treatment Arm, with Drinking Variables at Baseline

|

Total Sample

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1 | DrInC Total Score B (SE) |

β | % Drinking Days B (SE) |

β | % Heavy Days B (SE) |

β | #Drinks/Drinking Day B (SE) |

β |

| EP | −2.34 (1.12)* | −0.07 | −2.47 (1.37) | −0.06 | −2.25 (1.46) | −0.05 | 0.26 (0.40) | 0.02 |

| SS-Friends | −2.37 (1.00)* | −0.09 | −0.32 (1.09) | −0.01 | −2.16 (1.31) | −0.06 | −0.72 (0.33)* | −0.08 |

| SS-Family | −2.85 (0.87)** | −0.11 | 0.85 (0.99) | 0.03 | 0.16 (1.12) | 0.01 | −1.31 (0.29)*** | −0.13 |

| Arm | 13.55 (1.21)*** | 0.29 | 7.09 (1.48) | 0.12 | 11.55 (1.60)*** | 0.18 | 5.80 (4.60)*** | 0.29 |

| Sex | 2.96 (1.50)* | 0.06 | 2.96 (1.74) | 0.04 | 5.12 (1.84)** | 0.07 | 4.70 (0.61)*** | 0.21 |

|

| ||||||||

| Males Only | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Block 2 | DrInC Total Score B (SE) | β | % Drinking Days B (SE) | β | % Heavy Days B (SE) | β | #Drinks/Drinking Day B (SE) | β |

|

| ||||||||

| EP | −5.18 (1.16)*** | −0.52 | −2.43 (1.09)* | −0.08 | −2.13 (1.18) | −0.07 | 0.39 (0.53) | 0.03 |

| SS-Friends | −4.07 (0.97)*** | −0.15 | 0.94 (1.47) | 0.03 | −0.70 (1.56) | −0.02 | −0.65 (0.44) | −0.05 |

| SS-Family | −4.27 (0.93)*** | −0.17 | 0.39 (1.26) | 0.01 | −0.11 (1.33) | −0.01 | −1.55 (0.37)*** | −0.14 |

| Arm | 14.08 (1.32)*** | 0.30 | 8.01 (1.67)*** | 0.14 | 13.41 (1.84)*** | 0.18 | 6.56 (0.56)*** | 0.32 |

|

| ||||||||

| Females Only | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Block 3 | DrInC Total Score B (SE) | β | % Drinking Days B (SE) | β | % Heavy Days B (SE) | β | #Drinks/Drinking Day B (SE) | β |

|

| ||||||||

| EP | 0.11 (1.39) | 0.01 | −0.57 (1.80) | −0.02 | −0.03 (1.94) | −0.001 | −0.01 (0.44) | 0.00 |

| SS-Friends | −1.39 (0.62)* | −0.16 | −2.64 (2.06) | −0.08 | −5.77 (2.44)* | −0.17 | −0.78 (0.42) | −0.10 |

| SS-Family | −1.06 (0.64) | −0.11 | 1.61 (1.95) | 0.05 | 1.46 (2.20) | 0.04 | −0.51 (0.42) | −0.06 |

| Arm | 10.88 (2.50)*** | 0.23 | 3.84 (3.25) | 0.06 | 5.21 (3.29) | 0.08 | 3.04 (0.74)*** | 0.19 |

Note. For Sex: (0=F;1=M);

Parameter estimate is significant at p<0.001 level;

Parameter estimate is significant at p<0.01 level;

Parameter estimate is significant at p<0.05 level

Given consistent differences on EP, SS-friends, and SS-family, the models were estimated in both males and females, independently. For males (Table 4, Block 2), EP was significantly, negatively associated with total drinking consequences and percent number of drinking days, but was not significantly related to percent number of heavy drinking days or number of drinks per drinking day. SS-friends and SS-family were both significantly associated with drinking consequences for males, and SS-family was significantly associated with number of drinks per drinking day (see Table 4, Block 2). For females, only SS-friends was significantly associated with any of the drinking variables: total drinking consequences and percent heavy drinking days (Table 4, Block 3).

4. Discussion

The structural models illustrate that EP was related to drinking consequences and frequency of days in which alcohol was consumed but not frequency of days in which alcohol was consumed heavily or intensity of drinking on drinking days. These effects were largely driven by male drinkers. This is the first study to demonstrate that EP is associated with drinking frequency and consequences, independent of SS, and further demonstrates major differences between the sexes on levels of EP, SS-friends, and SS-family. While SS-friends was the only latent factor related to any drinking variables for females, all three latent factors were associated with drinking for males, including EP predicting fewer drinking consequences and lower frequency of drinking days at baseline.

More generally, results suggest that EP, SS-friends and SS-family are more meaningfully related to drinking for males. Of the constructs examined, only SS-friends was associated with drinking among females. Sex differences on the latent factors suggest males showed lower EP and endorsed lower levels of SS-friends but higher SS-family compared to females. The exact mechanism by which drinking and EP are related for men may be multi-faceted. Greater drinking frequency and drinking-related problems might result in lower EP abilities or vice versa. For example, drinking may impact the neural circuitry involved in the insight needed to adequately appraise drinking consequences for oneself and others. Alternatively, males with spared EP might be sensitive to drinking consequences and therefore EP may be associated with lower drinking frequency and fewer drinking-related problems. Although much work remains to disentangle the exact nature of EP deficits in males with AUD, our results generally agree with previous research on associations between deficits in EP and symptoms of AUD and research examining sex differences on both empathy (Baez et al., 2017) and drinking (Zilberman et al., 2003).

Post-hoc analyses indicated no associations between baseline EP and drinking outcomes following treatment (immediately post-treatment and up to one year post-treatment) in Project MATCH. Items indicating the EP construct were only assessed at baseline, hence we could not look at change in EP longitudinally. From a clinical perspective, EP may have been impacted by some of the behavioral treatments in Project MATCH, although none were designed to explicitly target EP and the construct itself was not explicitly measured. However, in this same dataset, individuals sponsoring other AUD patients (a natural tenet of the TSF program) during treatment were more likely to have better drinking outcomes than those not helping others (Pagano et al., 2004). MET was shown to be helpful for patients testing high in anger, theoretically due to its empathy-based treatment style (Moos, 2007). These indications of potential EP change may explain why baseline scores on EP were not predictive of post-treatment drinking. Future research exploring EP changes over time will be critical to ascertain whether the construct could be a mechanism of change. At the most practical level, increasing trait-level EP in heavy drinkers could lead to greater awareness of drinking consequences motivating change.

4.1. Limitations

Because the current study was an initial attempt at validating the EP construct in the Project MATCH sample, we focused on initial measurement modeling of EP and baseline correlations between EP, SS, and drinking. The items used as indicators of EP were only assessed at baseline, thus we could not look at change in EP during and after treatment. Further, while sex differences on EP and SS emerged in the present analysis, generalizing these to community drinkers or non-drinkers is not possible without replication in those samples. An additional caution of the current work is that the EP and SS factors did not explain a large amount of variance in drinking behavior. Thus, we can conclude that these factors are significantly, albeit modestly, associated with drinking in an AUD sample. Moreover, the operational definition of EP and the items selected to represent this latent factor were specific to the current investigation and should be replicated in future studies.

4.2. Conclusions and Future Directions

The present analysis supported EP as associated with SS, drinking consequences, and percent drinking days specifically for males within a large sample of treatment seekers with AUD. Motivating awareness of the impact of drinking behavior on the lives of others might supplement current treatments for problem drinking. Future research should consider measuring EP longitudinally among AUD samples and examine whether EP may mediate the effectiveness of existing behavioral interventions for AUD, particularly in males.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [R01 AA022328 (Witkiewitz, PI); T32 AA018108 (McCrady, PI); R01 AA023665-02S1 (Claus/Witkiewitz, PI)]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of NIH.

References

- Baez S, Flichtentrei D, Prats M, Mastandueno R, Garcia AM, Cetkovich M, Ibanez A. Men, women… who cares? A population-based study on sex differences and gender roles in empathy and moral cognition. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0179336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie MC, Longabaugh R. General and alcohol-specific social support following treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24(5):593–606. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JB, McClellan ML, Reed BG. Sex differences, gender and addiction. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2017;95:136–147. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107(2):238–46. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco FM, Capozzi F, Colle L, Marostica P, Tirassa M. Theory of mind deficit in subjects with alcohol use disorder: An analysis of mindreading processes. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2014;49(3):299–307. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;44(1):113–126. [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH. Empathy: Negotiating the border between self and other. In: Tiedens LZ, Leach CW, editors. The social life of emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004. pp. 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Maturing out of alcohol dependence: The impact of transitional life events. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(2):195–203. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dethier M, Blairy S. Capacity for cognitive and emotional empathy in alcohol-dependent patients. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(3):371–381. doi: 10.1037/a0028673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoldre I, Davis MH, Verhofstadt LL, Buysse A. Empathy and social support provision in couples: Social support and the need to study the underlying processes. The Journal of Psychology. 2010;144(3):259–284. doi: 10.1080/00223981003648294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari V, Smeraldi E, Bottero G, Politi E. Addiction and empathy: A preliminary analysis. Neurological Sciences. 2014;35(6):855–859. doi: 10.1007/s10072-013-1611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigerio E, Burt DM, Montagne B, Murray LK, Perrett DI. Facial affect perception in alcoholics. Psychiatry Research. 2002;113(1):161–171. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00244-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher KE, Hudepohl AD, Parrott DJ. Power of being present: The role of mindfulness on the relation between men’s alcohol use and sexual aggression toward intimate partners. Aggressive Behavior. 2010;36(6):405–413. doi: 10.1002/ab.20351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough HG. Theory, development, and interpretation of the CPI socialization scale. Psychological Reports. 1994;75(1):651–700. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1994.75.1.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden SL, Gfroerer JC. Correlates of perceiving a need for treatment among adults with substance use disorder: Results from a national survey. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(12):1213–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidari S, Babor TF, DeCastro P, Tort S, Curno M. Sex and Gender Equity in Research: Rationale for the SAGER reporting guidelines and recommended use. Research Integrity and Peer Review. 2016;1:2. doi: 10.1186/s41073-016-0007-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld RMA, Klerman GL, Gough HG, Barrett J, Korchin SJ, Chodoff P. A measure of interpersonal dependency. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1997;41(6):610–618. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4106_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Martins SS, Blanco C, Hasin DS. Telescoping and gender differences in alcohol dependence: New evidence from two national surveys. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:969–976. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kornreich C, Brevers D, Canivet D, Ermer E, Naranjo C, Constant E, Noël X. Impaired processing of emotion in music, faces and voices supports a generalized emotional decoding deficit in alcoholism. Addiction. 2013;108(1):80–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CH. Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behavior Research Methods. 2016;48(3):936–949. doi: 10.3758/s13428-015-0619-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey SH, Newmark RL, Wakschlag LS. Explicating the role of empathic processes in substance use disorders: A conceptual framework and research agenda. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2017 doi: 10.1111/dar.12548. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurage P, Campanella S, Philippot P, Charest I, Martin S, de Timary P. Impaired emotional facial expression decoding in alcoholism is also present for emotional prosody and body postures. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2009;44(5):476–485. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurage P, Grynberg D, Noël X, Joassin F, Philippot P, Hanak C, Campanella S. Dissociation between affective and cognitive empathy in alcoholism: A specific deficit for the emotional dimension. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011a;35(9):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurage P, Grynberg D, Noël X, Joassin F, Hanak C, Verbanck P, Philippot P. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” test as a new way to explore complex emotions decoding in alcohol dependence. Psychiatry Research. 2011b:375–378e. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady B. To have but one true friend: Implications for practice of research on alcohol use disorders and social network. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(2):113–121. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Del Boca FK. Measurement of drinking behavior using the Form 90 family of instruments. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 1994;(12):112–118. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R. The drinker inventory of consequences (DrInC) Project MATCH monograph series. 1995;4 [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH. Theory-based active ingredients of effective treatments for substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88(2):109–121. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pagano ME, Friend KB, Tonigan JS, Stout RL. Helping other alcoholics in alcoholics anonymous and drinking outcomes: Findings from project MATCH. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(6):766–773. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippot P, Kornreich C, Blairy S, Baert I, Dulk AD, Bon OL, Verbanck P. Alcoholics’ deficits in the decoding of emotional facial expression. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23(6):1031–1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procidano ME, Heller K. Measures of perceived social support from friends and from family: Three validation studies. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1983;11(1):1–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00898416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:7–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg H. Relapsed versus non-relapsed alcohol abusers: Coping skills, life events, and social support. Addictive Behaviors. 1983;8(2):183–186. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(83)90012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Plant RW, O’Malley S. Initial motivations for alcohol treatment: Relations with patient characteristics, treatment involvement, and dropout. Addictive Behaviors. 1995;20(3):279–297. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)00072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW. Motivation as a predictor of early dropout from drug abuse treatment. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1993;30(2):357–368. [Google Scholar]

- Spence JT, Helmreich RL, Stapp J. The Personal Attributes Questionnaire: A measure of sex role stereotypes and masculinity-femininity. Journal Supplement Abstract Service, American Psychological Association 1974 [Google Scholar]

- Tucker J, Vuchinich R, Pukish M. Molar environmental contexts surrounding recovery from alcohol problems by treated and untreated problem drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1995;3(2):195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker J, Vuchinich R, Rippens P. A factor analytic study of influences on patterns of help-seeking among treated and untreated alcohol dependent persons. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;26:237–242. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00209-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzun Ö. Alexithymia in male alcoholics: Study in a Turkish sample. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2003;44(4):349–352. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherington CL. Sex-gender differences in drug abuse: A shift in the burden of proof? Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15:411–417. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.5.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Marlatt G. Relapse prevention for alcohol and drug problems: That was Zen, this is Tao. American Psychologist. 2004;59(4):224–235. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.4.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberman M, Tavares H, el Guebaly N. Gender similarities and differences: The prevalence and course of alcohol- and other substance-related disorders. Journal of Addictive Disease. 2003;22:61–74. doi: 10.1300/j069v22n04_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]