Abstract

Amyloid β (Aβ)1–42 is strongly associated with Alzheimer's disease (AD). The effects of Aβ1–42 on astrocytes remain largely unknown. The present study focused on the effects of Aβ1–42 on U87 human glioblastoma cells as astrocytes for in vitro investigation and mouse brains for in vivo investigation. The mechanism and regulation of mitochondria and cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR) were also investigated. As determined by MTT assays, low doses of Aβ1–42 (<1 µM) marginally promoted astrocytosis compared with the 0 µM group within 24 h, however, after 48 h treatment these doses reduced cellular growth compared with the 0 µM group. Furthermore, Aβ1–42 doses >5 µM inhibited the growth of U87 cells compared with the 0 µM group after 24 and 48 h treatment. Immunofluorescence analysis demonstrated that astrocytosis was also observed in early stage AD mice compared with wild-type (WT) mice. In addition, concentrations of Aβ1–42 were also significantly higher in early stage AD mice compared with WT mice, however, the levels were markedly lower compared with later stage AD mice, as determined by ELISA. In addition to increased levels of Aβ1–42 in mice with later stage AD, reduced astrocyte staining was observed compared with WT mice. Western blotting indicated that the effect of Aβ1–42 on U87 cell apoptosis may be regulated via Bcl-2 and caspase-3 located in mitochondria, whose functions, including adenosine triphosphate generation, electron transport chain and mitochondrial membrane potential, were inhibited by Aβ1–42. During this process, the expression and activity of cytochrome P450 reductase was also downregulated. The current study provides novel insight into the effects of Aβ1–42 on astrocytes and highlights a potential role for astrocytes in the protection against AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, amyloid β1–42, astrocytosis, apoptosis, mitochondria, cytochrome P450 reductase

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a chronic neurodegeneration with symptoms that affect language and motivation, and cause behavioral and orientational disorders that gradually lead to patient mortality. The average life expectancy following AD diagnosis is usually within 10 years (1). There are ~48 million patients with AD worldwide, most of whom are >65 years old. Increasing evidence indicates that AD is partially caused by amyloid plaques in the brain (2). Amyloid plaques, composed of amyloid fibers, are extracellular deposits and the primary toxicant in AD brains. Amyloid β (Aβ) is the major component of amyloid plaques and has a central role in AD pathology (3). Aβ levels are elevated in AD brains, contributing to cerebrovascular lesions (4). Of the various Aβ oligomers, Aβ1–42 is the most amyloidogenic and fibrillogenic form of the peptide due to its hydrophobic nature, and therefore has a higher association with AD (5,6). The majority of previous studies have focused on the toxicity of Aβ1–42 on neurons (7–10). However, fewer studies have focused on the toxicity of Aβ1–42 on astrocytes, which also have important roles in AD.

Astrocytes are star-shaped macroglial cells, the most abundant cells in the central nervous system (CNS). They are responsible for ion exchange and uptake with neurons. Astrocytes also regulate the trophic factors, transmitters and transporters in CNS, modulating the normal neuron functions, synaptic activity and neuronal homeostasis. Astrocytes have critical roles in CNS energy provision, blood supply and synaptic activity regulations, homeostasis and remodeling in the brain. Dysfunctions of astrocytes are associated various brain diseases, including neurodegeneration (11,12). As the most neural toxic peptide, Aβ1–42 is highly associated with AD. However, the detailed effects and regulation pathway of Aβ1–42 on astrocytes are yet to be established.

As a double membrane-bound organelle and source of chemical energy (adenosine triphosphate; ATP) that is present in all eukaryotic organisms, mitochondria are involved in cell growth and apoptosis in the CNS. Mitochondrial dysfunction is implicated in several types of human neurodegeneration (13–15). Cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR), a 678-amino acid microsomal flavoprotein, is the obligate redox partner for all microsomal P450 cytochromes. CPR is required in all microsomal P450-catalyzed monooxygenase reactions, which catalyze the majority of the chemical metabolism in the human body (16–18).

In the present study, the U87 human glioblastoma cell line was used as astrocytes and treated with different doses of Aβ1–42 for different durations. The effects of Aβ1–42 on U87 cells and the regulation of CPR were detected. Furthermore, in vivo detection of Aβ1–42 levels and astrocytes was performed in AD and wild-type (WT) mice. The current study meets ethical guidelines and all research was approved by the Research Management Office and Experimental Animal Center of Suzhou Vocational Health College (Suzhou, China).

Materials and methods

Cells and chemicals

The U87MG ATCC human glioblastoma cell line, termed U87 throughout the manuscript, was kept in our laboratory for a long time. The original cell line was purchased from the Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). U87 cells were kept in Thermo Scientific incubator at 37°C, 5% CO2 with saturated humidity and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Hyclone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Shanghai ExCell Biology, Inc., Shanghai, China), 100 U/ml penicillin and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin (Hyclone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The sequence of Aβ1–42 peptide (molecular weight, 4,514.08 Da; Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was as follows: DAEFRHDSGYEVHHQKLVFFAEDVGSNKGAIIGLMVGGVVIA. Aβ1–42 was initially dissolved at a concentration of 1 mM in dimethyl sulfoxide, and 100 µl Aβ1–42 was combined with 900 µl PBS to generate 100 µM Aβ1–42. The product was incubated at 37°C for 7 days prior to use.

Detection on the cellular proliferation

Cellular proliferation was recorded using MTT reagent (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China) following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, U87 cells were seeded at a density of 3×103 cells per well, attached on the well and cultured with 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 20 and 50 µM Aβ1–42 at 37°C for 24 and 48 h. Subsequently, 20 µl MTT (5 mg/ml) was added to each well and incubated for 4 h at 37°C. Medium was removed and 150 µl formazan solvent was added for 15 min. The absorbance at 590 nm was recorded. This experiment was repeated three times.

Detection of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) expression

The expression of the astrocyte marker GFAP on U87 cells (at a density of 5.0×104 viable cells/cm2) cultured with 0, 1, 10 and 20 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h at 37°C was detected using immunofluorescence. Cells were washed with 1X PBS three times, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min at room temperature and treated with 1X PBS containing 0.5% Triton-X-100 for 15 min on ice. Subsequently, blocking was performed using 10% normal goat serum (ab7481; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) for 1 h at room temperature. Following blocking, cells were incubated with rabbit monoclonal anti-GFAP (1:600; ab33922; Abcam) at 4°C overnight and were washed three times with 1X TPBS for 10 min. Goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 488; 1:400; ab150077; Abcam) secondary antibody was added for 1 h in a dark room at room temperature, followed by washing three times with 1X TPBS for 10 min. Photos were taken using a fluorescence microscope at ×100 magnification (Eclipse Ti-S; Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

In vivo detection of Aβ1–42 and astrocytes

APPswe/PSEN1dE9 male mice were purchased from the Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University (Nanjing, China). These double transgenic mice, originally generated in Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME USA), are well referred to and widely used as AD mice studies. A total of 3 male, 8-month-old mice (weighing 25.4±2.9 g) were used to represent early stage AD and 3 12-month-old mice (weighing 26.1±4.5 g) were used for a later/progressed stage of AD. Then 3 8-month-old C57BL/6J mice (weighing 24.7±3.4 g) and 3 12-month-old C57BL/6J mice (weighing 24.3±4.0 g) were used as WT mice. The mice were raised in an environment with a temperature of 24±2°C, humidity of 55±15% and a 12-h light/dark cycle. Mice were given ad libitum access to food and water. Experiments and surgeries on the mice were performed according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines. Mouse brain cortex tissues were homogenized in cell lysis buffer which contains 25 mM HEPES, 125 µM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 100 µg/ml Leupeptin and 20 µg/ml Aprotinin. Concentration of Aβ1–42 in mouse brains was detected using an Amyloid β 42 Mouse ELISA kit (KMB3441; Novex; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The final results were calculated by comparing to the standard curve and presented in ng/mg protein. Mice brains were embedded in OTC on dry ice and cut into 10 µm frozen sections. Slides were placed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min at room temperature, then in 10% normal goat serum for 20 min also at room temperature. Astrocytes in the hippocampus region of mice were detected using GFAP primary antibody (ab7260; 1:200; Abcam) at 4°C overnight and goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 488; ab150077; 1:400; Abcam) secondary antibody at room temperature for 2 h. The present study was approved by the Experimental Animal Center of Suzhou Vocational Health College.

Detection of apoptosis by DAPI staining

U87 cells at a density of 5.0×104 viable cells/cm2 were cultured in the incubator and treated with 10 µM Aβ1–42 at 37°C for 48 h. Apoptosis was detected using DAPI staining (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Normal cells exhibit a round nucleus uniformly stained with clear margin, while apoptotic cells exhibit abnormal nucleus margin and the condensed chromosomes. Following fixation with 4% PFA for 20 min at room temperature and treatment with 1X TPBS (0.5% Triton-X-100) for 10 min on ice, cells were stained with DAPI solution for 15 min at room temperature. Images were acquired using a fluorescence microscope at ×100 and ×200 magnification (Eclipse Ti-S; Nikon Corporation).

Detection of apoptosis and CPR by western blot analysis

U87 cells were treated with 10 µM Aβ1–42 in an incubator at 37°C for 48 h. Protein was extracted from U87 cells using the above mentioned cell lysis buffer and quantified with Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (23225; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Protein (25 µg per lane) was detected using western blot analysis. Following electrophoresis and transfer to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), the membrane was blocked with 5% fat-free milk for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with anti-Bcl-2 (rabbit polyclonal IgG; 12789-1-AP; 1:1,000; ProteinTech Group, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA,), anti-cleaved caspase-3 (9661; 1:800; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and anti-CPR (rabbit polyclonal IgG; ab13513; 1:1,000; Abcam) primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Subsequently, membranes were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (ab6721; 1:5,000; Abcam) at room temperature for 2 h. GAPDH (ab9485; 1:2,500; Abcam,) was used as a loading control indicator.

Detection of CPR activity

U87 cells at a seeding density of 5.0 × 104 viable cells/cm2 were treated with 10 µM Aβ1–42 in a cell culture incubator at 37°C for 48 h. The microsome of U87 cells was homogenized on ice in 10 mM PBS (pH 7.7) containing 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA and 0.5 mM PMSF for 15 sec then centrifuged for 20 min at 10,000 × g at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and centrifuged for 1 h at 40,000 × g at 4°C, then the supernatant was decanted. The pellet was re-suspended in 0.1 M PBS containing 1 mM EDTA, 1mM dithiothreitol, 30% glycerol and protease inhibitors (pH 7.25). The activity of CPR in microsome was detected in the reduction of cytochrome c determined in reactions. Briefly, 80 µl of a 0.5-mM solution of the horse heart cytochrome c (in 10 mM PBS, pH 7.7) was added into a glass with an aliquot of sample. Then 10 µl of a 10 mM NADPH solution was added and A550 was recorded using the spectrophotometer as a function of time (about 3 min). The rate of reduction of cytochrome c was calculated as ΔA550 min−1/0.021=nmol of cytochrome c reduced per min.

Detection of mitochondrial functions

The mitochondrial functions of U87 cells at a density of 5.0×104 viable cells/cm2 cultured with 0, 1, 10 and 20 µM Aβ1–42 in a cell culture incubator at 37°C for 48 h was detected. ATP generation was detected using an ATP assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 200 µl lysis buffer was added to U87 cells cultured in 6-well plates, which were subsequently centrifuged at 12,000 × g at 4°C for 5 min. The supernatant was collected and detected together with ATP standard solution on the luminometer. Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was detected using a JC-1 staining kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's protocol. In addition, the activity of the four complexes of the electron transport chain (ETC) following treatment of U87 cells with 10 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h were also detected using MitoCheck Complex Activity Assay Kit (I: 700930, II: 700940, III: 700950 and IV: 700990; Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, Catalog No.). The rate of NADH oxidation was measured at 340 nm for the activity of complex I. A decrease in absorbance at 600 nm for complex II activity, the reduction of excess cytochrome c (550 nm absorbance) for complex III and the direct oxidation of cytochrome c for complex IV. Results were presented relative to values in the control (0 µM) group.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation and analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Results were evaluated using Student's t-test for two-group comparison or one-way analysis of variance followed by a post hoc Dunnett's test for multiple groups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Effects of Aβ1–42 on the proliferation of U87 cells

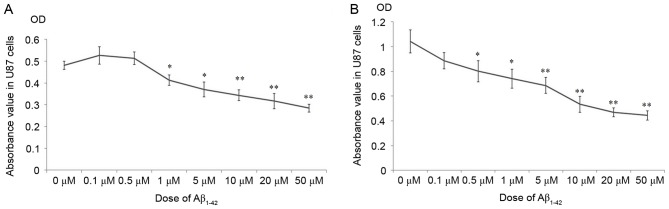

As demonstrated in Fig. 1, the cellular growth of U87 was significantly inhibited following treatment with >1 µM Aβ1–42 at 24 h (Fig. 1A) and 48 h (Fig. 1B), compared with the 0 µM group. Surprisingly, doses of Aβ1–42 <1 µM marginally promoted the cellular growth at 24 h (Fig. 1A), however, after 48 h treatment these doses inhibited growth compared with the 0 µM group (Fig. 1B). These results indicate that the effects of Aβ1–42 on the proliferation of U87 cells were complex. Small doses of Aβ1–42 promoted the proliferation of U87 cells for the initial 24 h, while doses >1 µM inhibited the growth of U87 cells after 24 h. After a longer treatment duration of 48 h, the proliferation of U87 cells was arrested compared with the 0 µM group at all Aβ1–42 doses.

Figure 1.

The cellular proliferation of U87 cells was detected using MTT assays. U87 cells were treated with 0–50 µM Aβ1–42 for (A) 24 h and (B) 48 h. Aβ, amyloid β; OD, optical density. *P<0.05 vs. 0 µM Aβ1–42 group, **P<0.01 vs. 0 µM Aβ1–42 group.

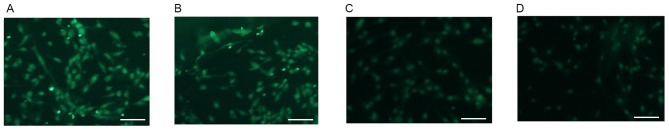

Alterations in the expression of GFAP in U87 cells

Various reports have indicated that U87 human glioblastoma cells may be used as astrocytes for AD neuropathology and cytotoxicity studies (19–21). As a cellular marker of astrocytes, GFAP (green staining) was highly expressed on U87 cells that were not treated with Aβ1–42 (0 µM group; Fig. 2A). The expression of GFAP was markedly decreased in a dose-dependent manner in Aβ1–42 treatment groups after 48 h treatment. Representative images of GFAP staining in cells treated with 1, 10 and 20 µM Aβ1–42 are presented in Fig. 2B-D.

Figure 2.

The expression of GFAP in U87 cells following treatment with Aβ1–42 for 48 h using immunofluorescence. U87 cells were treated with (A) 0 µM, (B) 1 µM, (C) 10 µM and (D) 20 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h. GFAP expression stained green. Photos were taken using a fluorescence microscope at ×100 magnification. Scale bar, 100 µm. GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; Aβ, amyloid β.

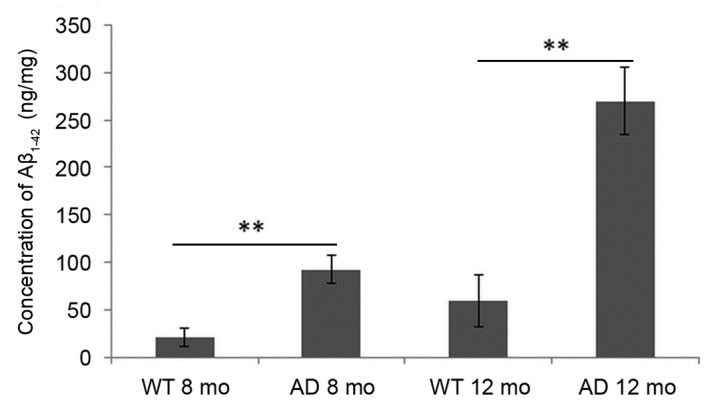

Alterations in the concentration of Aβ1–42 in the mouse brain cortex

As demonstrated in Fig. 3, compared with WT mice, the concentration of Aβ1–42 in the cortex of mice brains was significantly increased in AD mice at early AD stage (8 months) and AD progressed stage (12 months). Levels were barely detected in WT mice at 8 months and marginally increased at 12 months. Even in AD mice, the concentration of Aβ1–42 at the early stage (8 months) was low compared with levels at 12 months.

Figure 3.

Concentration of Aβ1–42 in the WT and AD mouse brain cortex at early and progressed stages of AD. Mice at 8-months of age were considered to be early stage AD mice and 12-month-old mice were used as progressed AD stage mice. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. **P<0.01 vs. WT mice at the same age. Aβ, amyloid β; WT, wild-type; AD, Alzheimer's disease; mo, months.

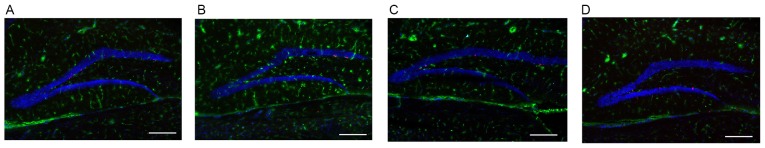

Abnormal astrocytes in hippocampus region of AD mice brain

Compared with WT mice, the number of astrocytes in the hippocampus region of the AD mouse brain was visibly increased at the early stage of AD (8 months; Fig. 4A and B). This process is termed astrocytosis. During this period (8 months), the concentration of Aβ1–42 was at a low level (Fig. 3). However, at 12 months, the level of Aβ1–42 was increased significantly in AD mice (Fig. 3). The number of astrocytes in the hippocampus region of the AD mouse brain was markedly decreased in progressed AD (12 months) mice compared with the WT group (Fig. 4C and D).

Figure 4.

Detection of astrocytes in the hippocampus region of the mouse brain. Astrocytes were identified as GFAP-positive cells (green). Cell nuclei were stained blue by DAPI staining. Representative photos for GFAP staining in (A) WT mice at 8 months, (B) AD mice at 8 months, (C) WT mice at 12 months and (D) AD mice at 12 months. Scale bar, 100 µm; magnification, ×100. GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; WT, wild-type; AD, Alzheimer's disease.

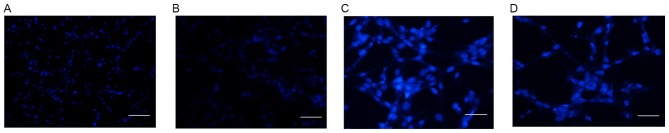

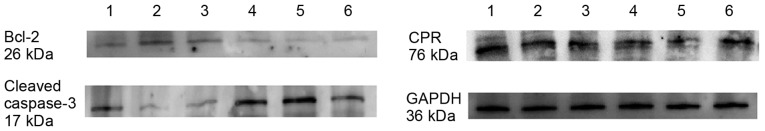

The effects of Aβ1–42 on apoptosis in U87 cells

The cellular apoptosis of U87 cells was detected by DAPI staining in control cells and cells treated with 10 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h at magnifications of ×100 (Fig. 5A and B, respectively) and ×200 (Fig. 5C and D, respectively). As demonstrated in Fig. 5, no obvious apoptosis was detected in the control group (Fig. 5A and C). However, following treatment with 10 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h, obvious apoptosis was detected by abnormal cell nucleus staining (Fig. 5B and D). Furthermore, the protein expression of the apoptosis factors Bcl-2 and cleaved caspase-3 were detected by western blot analysis following treatment of U87 cells with 10 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h. Lanes 1–3 represent protein expression in control U87 cells and lanes 4–6 represent protein expression in U87 cells treated with 10 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h (Fig. 6). As demonstrated in Fig. 6, the expression of Bcl-2 was markedly decreased following treatment with 10 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h compared with the control group, and the opposite was observed for the expression of cleaved caspase-3, which was markedly increased following treatment with 10 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h compared with control cells. Furthermore, the expression of CPR was determined by western blotting. Generally, the expression of CPR was downregulated following treatment with 10 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h. However, the individual differences among samples were obvious (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Detection of apoptosis in U87 cells treated with 10 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h using DAPI staining. Cell nuclei were stained in blue. Representative photos for DAPI staining in U87 cells treated with (A) 0 µM and (B) 10 µM Aβ1–42 at ×100 magnification. Scale bar, 100 µm. Representative photos for DAPI staining in U87 cells treated with (C) 0 µM and (D) 10 µM Aβ1–42 at ×200 magnification. Scale bar, 50 µm. Aβ, amyloid β.

Figure 6.

The protein expression of Bcl-2, cleaved caspase-3 and CPR in U87 cells was determined by western blotting. Representative western blot results for U87 cells treated with 0 and 10 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h. Lanes 1–3 represent results from the 0 µM group and lanes 4–6 represent results from cells treated with 10 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h. CPR, cytochrome P450 reductase; Aβ, amyloid β.

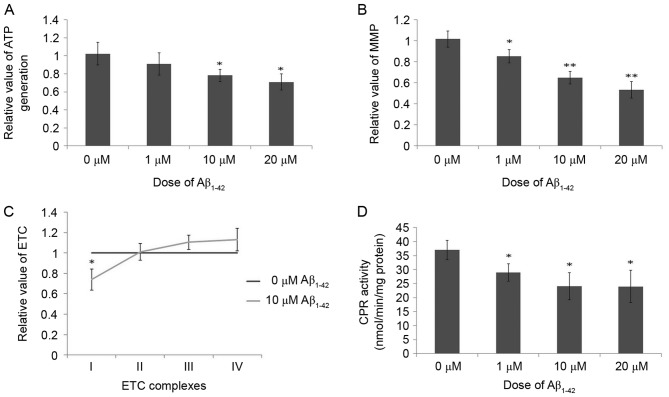

The effects of Aβ1–42 on mitochondrial functions

ATP generation was downregulated following treatment with Aβ1–42 for 48 h in a dose-dependent manner compared with the control group, and these differences were significant at 10 and 20 µM Aβ1–42 (Fig. 7A). As demonstrated in Fig. 7B, due to the toxicity of Aβ1–42 on mitochondria, the MMP was significantly decreased in cells treated with Aβ1–42 for 48 h in a dose-dependent manner compared with control cells. Additionally, the activity of complex I of the ETC was markedly decreased, while the activities of complexes III and IV were marginally increased, following treatment with 10 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h compared with control cells (Fig. 7C). No obvious difference was observed for complex II activity in control cells and cells treated with 10 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h (Fig. 7C). These results indicate the obvious toxicity of Aβ1–42 on mitochondria as certain functions of mitochondria were inhibited following treatment with Aβ1–42.

Figure 7.

The mitochondrial function and CPR activity of U87 cells. (A) ATP generation of U87 cells treated with 0–20 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h. (B) MMP in cells treated with 0–20 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h. (C) Activity of complexes of the ETC in cells treated with 0 and 10 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h. (D) CPR activity in U87 cells treated with 0–20 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. 0 µM group. CPR, cytochrome P450 reductase; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; Aβ, amyloid β; MMP, mitochondrial membrane potential; ETC, electron transport chain.

The effects of Aβ1–42 on the activity of CPR

CPR has a key role in the metabolism of chemicals (22). Enzymes are regulated in two ways, one is expression regulation (slow adjustment) and the other is activity regulation (rapid adjustment). Generally, effects due to the regulation of expression are slow while effects of activity regulation occur more rapidly. However, expression and activity regulation are both important for the catalyst function of an enzyme. Therefore, the present study detected the expression and activity of CPR. The results for CPR expression were described above for western blotting results in Fig. 6. Concerning CPR activity, the CPR activity, in the reduction of cytochrome c, was markedly inhibited following treatment with 10 µM Aβ1–42 for 48 h compared with control cells (Fig. 7D).

Discussion

AD was first observed, described and named by Alois Alzheimer, a German psychiatrist and pathologist in 1906. It is a serious chronic neurodegeneration without effective drugs currently. The morbidity of AD has been increasing rapidly in recent years. Aβ is formed following sequential cleavage of a transmembrane glycoprotein termed amyloid precursor protein (APP) (23). Various isoforms of 30–51 amino acid residues are generated by cleavage by α-, β- and γ- secretases, of which the most common isoforms are Aβ1-40 and Aβ1–42. Aβ1–42 is the most fibrillogenic and is highly associated with AD (24). An increased understanding of the effects of Aβ1–42 on astrocytes, not only on neurons as numerous previous studies have focused on, is essential. As a common and routine method, the present study used U87 human glioblastoma cells as astrocytes. Initially, MTT assays were performed to investigate the effect of Aβ1–42 on the growth of U87 cells. High doses of Aβ1–42 (>1 µM) led to growth inhibition. However, low doses of Aβ1–42 (<1 µM) marginally promoted the cellular growth after 24 h, but inhibited growth after 48 h. These effects were dose-dependent, which means that different doses of chemicals lead to different levels of effects. However, it is still surprising that low and higher doses of Aβ1–42 led to opposing effects after 24 h treatment. Furthermore, U87 cells treated with a low dose of Aβ1–42 (1 µM) exhibited abnormal growth termed astrocytosis. These results were also confirmed by in vivo experiments using double transgenic mice that express APP and the mutant presenilin 1, and are widely used as AD mice. Compared with WT mice, the number of astrocytes in the hippocampus region of the AD mouse brain was increased at the early stage of AD with a low Aβ1–42 level, while astrocytes were obviously decreased in the brains of AD at 12 months with an increased Aβ1–42 level. Astrocytosis, also termed reactive astrogliosis, consists of abnormal reactive astrocytes and is often observed as an early phenomenon in AD development (25,26). Reactive astrocytes colocalize with Aβ plaques in AD brains. Astrocytosis harms surrounding neural cells, resulting in damage to neural functions, glial scarring and inflammation in the brain (27). Reactive astrocytes may promote neural toxicity via the generation of cytokines, which may subsequently damage nearby neurons. In addition, they may also promote secondary damage or degeneration following CNS injury (28).

As a form of abnormal proliferation, astrocytosis is temporary, occurring only at the beginning of cellular growth or in the early stage of AD. Two different abnormal pathological astrocytes have been reported (29–31). To detect the effect of Aβ1–42 on apoptosis, DAPI staining was performed. As a fluorescent stain, DAPI binds strongly to DNA and is used extensively in apoptosis detection. Apoptosis, a process of programmed cell death that is regulated by various factors, inevitably leads to cellular death. Caspase-3 and Bcl-2 are key factors involved in apoptosis. Caspase-3 is activated, following cleavage by an initiator caspase, in apoptotic tissues and cells partially by mitochondrial regulation and has a dominant role in apoptosis (32). In the present study, increased activation of caspase-3 was observed following treatment with Aβ1–42. As an important anti-apoptotic oncogene, Bcl-2 is localized to the outer membrane of mitochondria, and has a key role in the promotion of cellular survival and inhibition of apoptosis (33). Reduced expression of Bcl-2 was observed following treatment of cells with Aβ1–42 in the present study. As caspase-3 and Bcl-2 are located on and regulated via mitochondria, the present study subsequently investigated the function of mitochondria.

As a source of chemical energy in the form of ATP, the mitochondrion is a double membrane-bound organelle that is widely distributed in the majority of eukaryotic cells. In the current study, the results demonstrated that ATP generation was significantly decreased in a dose-dependent manner following 48 h treatment with Aβ1–42, which indicates that the primary function of mitochondria was inhibited by Aβ1–42. In addition to supplying cellular energy, mitochondria are also involved in cell growth and apoptosis in AD (34,35). Mitochondrial dysfunction has been implicated in several human diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and schizophrenia (13–15). All of these reports are in accordance with the results of the present study. ETC, a chain that consists of a series of compounds containing certain complexes, transfers electrons from donors to acceptors via redox reactions and couples electron transfer with the transfer of protons. This process creates an electrochemical proton gradient that drives the generation of Mitochondrial ATP (36). The present study demonstrated that, compared with other complexes and the activity in control cells, the activity of complex I of the ETC was decreased following treatment with Aβ1–42. MMP is critical for maintaining the normal functions of the ETC in mitochondria to generate ATP. Loss of MMP leads to the depletion of ATP and therefore energy in cells, eventually resulting in apoptosis or necrosis. The current study demonstrated that the MMP was markedly decreased following treatment with Aβ1–42 for 48 h in a dose-dependent manner, which further impairs the generation of ATP. These observations may partially explain the reduced ATP generation following treatment with Aβ1–42, indicating that Aβ1–42 may enter the mitochondria and interfere with the ETC and MMP, subsequently leading to inhibition of ATP production.

Cytochrome P450s, which have maximum absorption at ~450 nm, are a superfamily of hemoproteins that function as the terminal oxidase enzymes in the ETC. As a microsomal flavoprotein, CPR is the obligate redox partner for cytochrome P450s, transferring electrons from NADPH to cytochrome P450s. CRP is required for all microsomal P450-catalyzed monooxygenase reactions (37). Although various P450 subfamilies have important roles in the normal and pathological functions of astrocytes, CPR is the key enzyme. Inhibition of CPR would widely and largely reduce the function of all P450-mediated metabolism. Our previous research indicated that CPR was highly associated with astrocytosis (38). Furthermore, another study reported widespread distribution of CPR in neurons and glial cells in the brain, including in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus (39). The results of the present study indicated that Aβ1–42 marginally inhibited the expression of CPR in certain samples. However, the individual differences between individual samples was obvious, which indicates that the expression of CPR may be complex and regulated by various factors.

In conclusion, the current study indicated that low doses of Aβ1–42 (<1 µM) promoted astrocytosis temporarily after 24 h, but led to reduced astrocyte numbers with higher doses of Aβ1–42, which may occur by induction of apoptosis in U87 cells via regulation of Bcl-2 and caspase-3 expression. Furthermore, the functioning of mitochondria was inhibited by treatment with Aβ1–42. During this process, the expression, in certain samples, and activity of CPR were downregulated compared with control cells. The present study provides novel insights into the effects of Aβ1–42 on astrocytes and highlights astrocytes as a potential target for protection against AD.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant no. BK20130219), the National Nature Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81401045) and the Qing Lan Project of Jiangsu Province.

References

- 1.Iqbal K, Grundke-Iqbal I. Developing pharmacological therapies for Alzheimer disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:2234–2244. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7221-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Awasthi M, Singh S, Pandey VP, Dwivedi UN. Alzheimer's disease: An overview of amyloid beta dependent pathogenesis and its therapeutic implications along with in silico approaches emphasizing the role of natural products. J Neurol Sci. 2016;361:256–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark IA, Vissel B. Amyloid β: One of three danger-associated molecules that are secondary inducers of the proinflammatory cytokines that mediate Alzheimer's disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:3714–3727. doi: 10.1111/bph.13181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blennow K, Mattsson N, Schöll M, Hansson O, Zetterberg H. Amyloid biomarkers in Alzheimer's disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36:297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang ZX, Tan L, Liu J, Yu JT. The essential role of soluble Aβ oligomers in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:1905–1924. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thal DR, Walter J, Saido TC, Fändrich M. Neuropathology and biochemistry of Aβ and its aggregates in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129:167–182. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1375-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ebenezer PJ, Weidner AM, LeVine H, III, Markesbery WR, Murphy MP, Zhang L, Dasuri K, Fernandez-Kim SO, Bruce-Keller AJ, Gavilán E, Keller JN. Neuron specific toxicity of oligomeric amyloid-β: Role for JUN-kinase and oxidative stress. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22:839–848. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bloom GS. Amyloid-β and tau: The trigger and bullet in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:505–508. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.5847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drolle E, Hane F, Lee B, Leonenko Z. Atomic force microscopy to study molecular mechanisms of amyloid fibril formation and toxicity in Alzheimer's disease. Drug Metab Rev. 2014;46:207–223. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2014.882354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rottkamp CA, Raina AK, Zhu X, Gaier E, Bush AI, Atwood CS, Chevion M, Perry G, Smith MA. Redox-active iron mediates amyloid-beta toxicity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:447–450. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00494-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liem RK, Messing A. Dysfunctions of neuronal and glial intermediate filaments in disease. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1814–1824. doi: 10.1172/JCI38003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tao YQ, Liang GB. Pathologic changes and dysfunctions of astrocytes in the complex rat AD model of ovariectomy combined with D-galactose injection. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2014;115:692–698. doi: 10.4149/bll_2014_134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onyango IG, Dennis J, Khan SM. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease and the rationale for bioenergetics based therapies. Aging Dis. 2016;7:201–214. doi: 10.14336/AD.2015.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haddad D, Nakamura K. Understanding the susceptibility of dopamine neurons to mitochondrial stressors in Parkinson's disease. FEBS Lett. 2005;589:3702–3713. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rajasekaran A, Venkatasubramanian G, Berk M, Debnath M. Mitochondrial dysfunction in schizophrenia: pathways, mechanisms and implications. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;48:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zanger UM, Schwab M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: Regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;138:103–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laursen T, Jensen K, Møller BL. Conformational changes of the NADPH-dependent cytochrome P450 reductase in the course of electron transfer to cytochromes P450. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1814:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coon MJ. Cytochrome P450: Nature's most versatile biological catalyst. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.100030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Cheng D, Cheng R, Zhu X, Wan T, Liu J, Zhang R. Mechanisms of U87 astrocytoma cell uptake and trafficking of monomeric versus protofibril Alzheimer's disease amyloid-β proteins. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99939. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deb S, Zhang JW, Gottschall PE. Activated isoforms of MMP-2 are induced in U87 human glioma cells in response to beta-amyloid peptide. J Neurosci Res. 1999;55:44–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990101)55:1<44::AID-JNR6>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai JC, Ananthakrishnan G, Jandhyam S, Dukhande VV, Bhushan A, Gokhale M, Daniels CK, Leung SW. Treatment of human astrocytoma U87 cells with silicon dioxide nanoparticles lowers their survival and alters their expression of mitochondrial and cell signaling proteins. Int J Nanomedicine. 2010;5:715–723. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S5238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iyanagi T. Structure and function of NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase and nitric oxide synthase reductase domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:520–528. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Brien RJ, Wong PC. Amyloid precursor protein processing and Alzheimer's disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:185–204. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hao J, Zhang W, Zhang P, Liu R, Liu L, Lei G, Su C, Miao J, Li Z. Abeta20-29 peptide blocking apoE/Abeta interaction reduces full-length Abeta42/40 fibril formation and cytotoxicity in vitro. Neuropeptides. 2010;44:305–313. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jain P, Wadhwa PK, Jadhav HR. Reactive astrogliosis: Role in Alzheimer's disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2015;14:872–879. doi: 10.2174/1871527314666150713104738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodríguez JJ, Olabarria M, Chvatal A, Verkhratsky A. Astroglia in dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:378–385. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Członkowska A, Kurkowska-Jastrzębska I. Inflammation and gliosis in neurological diseases-clinical implications. J Neuroimmunol. 2011;231:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agostinho P, Cunha RA, Oliveira C. Neuroinflammation, oxidative stress and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:2766–2778. doi: 10.2174/138161210793176572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh S, Joshi N. Astrocytes: Inexplicable cells in neurodegeneration. Int J Neurosci. 2017;127:204–209. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2016.1173692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robel S, Sontheimer H. Glia as drivers of abnormal neuronal activity. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:28–33. doi: 10.1038/nn.4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pekny M, Pekna M, Messing A, Steinhäuser C, Lee JM, Parpura V, Hol EM, Sofroniew MV, Verkhratsky A. Astrocytes: A central element in neurological diseases. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:323–345. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1513-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu D, Corbett B, Yan Y, Zhang GX, Reinhart P, Cho SJ, Chin J. Early cerebrovascular inflammation in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:2942–2947. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kvansakul M, Hinds MG. The Bcl-2 family: Structures, interactions and targets for drug discovery. Apoptosis. 2015;20:136–150. doi: 10.1007/s10495-014-1051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obulesu M, Lakshmi MJ. Apoptosis in Alzheimer's disease: An understanding of the physiology, pathology and therapeutic avenues. Neurochem Res. 2014;39:2301–2312. doi: 10.1007/s11064-014-1454-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ajith TA, Padmajanair G. Mitochondrial Pharmaceutics: A new therapeutic strategy to ameliorate oxidative stress in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Aging Sci. 2015;8:235–240. doi: 10.2174/187460980803151027115147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jonckheere AI, Smeitink JA, Rodenburg RJ. Mitochondrial ATP synthase: Architecture, function and pathology. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2012;35:211–225. doi: 10.1007/s10545-011-9382-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Estabrook RW. Steroid hydroxylations: A paradigm for cytochrome P450 catalyzed mammalian monooxygenation reactions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yao Y, Liu S, Wang Y, Yuan W, Ding X, Cheng T, Shen Q, Gu J. Suppression of cytochrome P450 reductase expression promotes astrocytosis in subventricular zone of adult mice. Neurosci Lett. 2013;548:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Norris PJ, Hardwick JP, Emson PC. Localization of NADPH cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase in rat brain by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization and a comparison with the distribution of neuronal NADPH-diaphorase staining. Neuroscience. 1994;61:331–350. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]