Abstract

Sick sinus syndrome (SSS) is a sinus node dysfunction characterized by severe sinus bradycardia. SSS results in insufficient blood supply to the brain, heart, kidneys, and other organs and is associated with the increased risk of sudden cardiac death. Bradyarrhythmia appears in the absence of any associated cardiac pathology and displays a genetic legacy. The present study identified a family with primary manifestation of sinus bradycardia (five individuals) along with early repolarization (four individuals) and atrial fibrillation (one individual). Targeted exome sequencing was used to screen exons and adjacent splice sites of 61 inherited arrhythmia-associated genes, to detect pathogenic genes and variant sites in the proband. Family members were sequenced by Sanger sequencing and protein functions predicted by Polyphen-2 software. A total of three rare variants were identified in the family, including two missense variants in calcium voltage-gated channel subunit alpha1 C (CACNA1C) (gi:193788541, NM_001129843), c.1786G>A (p.V596M) and c.5344G>A (p.A1782T), and one missense variant in titin (TTN) c.49415G>A (p.R16472H) (gi:291045222, NM_003319). The variants p.V596M and p.R16472H were predicted to be deleterious and resulted in alterations in the amino acid type and sequence of the polypeptide chain, which may partially or completely inactivate the encoded protein. The comparison of literature, gene database, and pedigree phenotype analysis suggests that p.V596M or p.R16472H variants are pathogenic. The complex overlapping variants at three loci lead to a more severe phenotype in the proband, and may increase the susceptibility of individuals to atrial fibrillation. The simultaneous occurrence of V596M and R16472H may increase the severity of early repolarization. Various family members may have carried heterozygous mutants of p.A1782T and p.R16472H due to genetic heterogeneity, however did not exhibit clinical signs of cardiac electrophysiological alterations, potentially attributable to the low vagal tone. To the best of the author's knowledge, this is the first study to suggest the involvement of the novel missense CACNA1C c.1786G>A and TTN c.49415G>A variants in the inheritance of symptomatic bradycardia and development of SSS.

Keywords: sinus bradycardia, early repolarization, atrial fibrillation, inherited arrhythmogenic disease, CACNA1C gene, TTN gene, variant

Introduction

Sick sinus syndrome (SSS) is caused by lesions in the sinoatrial node and its adjacent tissues, resulting in sinoatrial node pacemaker function and/or sinoatrial conduction dysfunction. SSS includes conditions such as severe sinus bradycardia, sinus arrest, sinoatrial block, and bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome (flutter, atrial fibrillation, and paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia) (1,2). SSS may lead to insufficient blood supply to the heart, brain, kidney, and other organs, and cause sudden cardiac death. Symptomatic SSS requires the implantation of an electronic pacemaker. SSS accounts for about half of all pacemaker implantations in the United States (3). Given the low survival rate (less than 10%) (4), the identification of patients with high-risk SSS is of importance for the prevention of sudden cardiac death.

Although a variety of pathological factors leading to sinus node or cardiac nerve dysfunction may cause SSS, a positive correlation was observed between SSS and age (5). Increasing evidences suggest a distinct genetic background in SSS, including some genetic mutations in genes encoding cytoskeletal proteins and ion channels that may result in familial sick sinus syndrome (FSSS). The L-type voltage-gated calcium channel (I-caL) is one of the significant ion channels involved in the automatic cell depolarization in sinoatrial node. Loss of I-cal in some hereditary SSS is of great significance. For instance, the deletion of L-calcium currents in CaV1.3 knockout mice (CaV1.3−/−) may contribute to reduced heart rate and sinus arrhythmia (6). The presence of CaV1.3-mediated I-caL dysfunction may clinically lead to sinus node dysfunction and deafness syndrome (SANDD). Individuals affected with SANDD present with bradycardia, profound deafness, and dysfunction of atrioventricular conduction (7). However, no study has reported the association between sinus bradycardia or SSS and the variant of calcium voltage-gated channel subunit alpha1 C (CACNA1C).

The early repolarization (ER) pattern displays two or more continuous wall or side wall leads with a J point elevation above 0.1 mV in the standard 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG). The ST elevation is above 0.1 mV and exhibits concave upward or oblique type elevation. ER is often inherited and several studies have shown its relationship with malignant arrhythmias and sudden death (8–10). It is known that ER syndrome is a polygenic inherited disease, similar to hereditary sinus bradycardia, caused by mutations in cardiomyocyte genes encoding ion channels. The most common pathogenic genes are encoded by cardiac electrical ion channels, including calcium channels (CACNA1C, CACNB2B, and CACNA2D1) (11), ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KCNJ8) (12), and sodium channel α subunit 5 (SCN5A) (13). Functional studies have revealed its association with ‘enhanced function’ or ‘loss of function’ of ion channels. A change of 1–5% was reported in the incidence of ER in the general population (14) and is most commonly seen in young men (15).

We applied next generation sequencing (NGS) for the identification of a genetically arrhythmic family of SSS and ER characterized by complex bradycardia to further understand the interaction between the complex genotype and phenotype in this family.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The proband of this family is a 76-year-old male patient from Fujian with Han nationality and clinical manifestation of recurrent palpitation, flustered, and bradycardia with irregularity. Multiple electrocardiographic examinations indicated that the patient had slow atrial fibrillation (the slowest heart rate 29 beats per min). According to the family data provided by the proband, medical records, routine physical examination, ECG, and cardiac ultrasound examination were performed for other 11 family members. In addition, blood, urine, biochemical kit, troponin, pro-BNP, etc., were analyzed and the family genetic map was recorded. The study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the hospital and all subjects signed the informed consent.

Genomic DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted with Tiangen blood genomic DNA extraction kit (DP348) as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Illumina sequencing (16–18) and bioinformatic analysis (19)

DNA samples of the proband were detected by Nanodrop 2000 and over 3 µg sample was used for DNA fragmentation. DNA fragments were interrupted to about 250 bp by Covaris method, followed by their recovery. The fragments were subjected to the end-repair reaction and the sequence-specific attachment (adapter) was linked with the end-repair products. The product was amplified and purified based on the universal primer-binding site on the adapter. For the capture and enrichment of the target, multiple gene fragments, including target genes CACNA1C and TTN, were enriched by DNA capture chip with multiple genes and the enrichment products were sequenced by Illumina (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) (5). For data analysis, the original file was subjected to base reading to obtain double terminal sequence of 90 bp reads. For the removal of the low-quality and polluted reads, the adapter sequence was removed and the purification data analyzed by sequence alignment. Soap software (SOAPdenovo V2.04; SOAP3/GPU V0.01beta; SOAPaligner/soap2 V2.20; SOAPsplice V1.1; SOAPsnp V1.03; SOAPindel V1.0; SOAPsv V1.02) was used to analyze copy number, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), and insertion/deletion (INDEL). Annotations were used to screen suspected pathogenic variants. The polymorphism phenotyping version 2 (Polyphen2) software was applied (genetices.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/) for the prediction of protein functions. The process was completed by Shenzhen Huada Genomics Institute in accordance with its operating standards.

Sanger sequencing

Variants were confirmed using Sanger DNA sequencing. The primers targeting the target sequence were designed using Primer Premier 5 software and synthesized by Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA). CACNA1C gene sequence was derived from GenBank (NM_001129843) and the target sequence was 230 bp. The primers used were as follows: Forward, GCTCGGATCTCATCCCTCTC and reverse, GACGCATCTGAGCACGGA. Another target sequence of CACNA1C was 260 bp long and the specific primers used were as follows: Forward, TTCACCCCGAGCAGCTAC and reverse, TCCACTGTCTCCTGAGGGTT. TTN gene sequence was obtained from GenBank (NM_003319) and the target sequence was 270 bp. The primers used were as follows: Forward, CATTGTCAAGAACAAGAGAGGTGAAAC and reverse, CGTATCTGTGCTATTAATAAAGCTGGAGT. Amplification of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products: The reaction was carried out in a final volume of 25 µl and comprised 2.5 µl of 10X Ex Taq buffer, 2 µl dNTP (2.5 mmol/l), 3 µl of each of forward and reverse primer (3 mmol/l), 1 µl DNA template, 0.2 µl Ex Taq, and 18.3 µl water. PCR products were amplified on PCR machine (PTC-200, PCR; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) under following conditions: Initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 40 sec, annealing at 58–62°C for 40 sec, extension at 72°C for 60 sec, followed by the final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Purification and sequencing of PCR products: PCR products were obtained from Omega corporation E.Z.N.A.™ Gel Extraction kit. Sequencing was performed according to the standard procedure of BigDye Terminator v1.1 kit PCR products. Sequencing results were obtained by comparing DNAMAN version 5.2.2 with the normal sequence.

Results

Clinical report

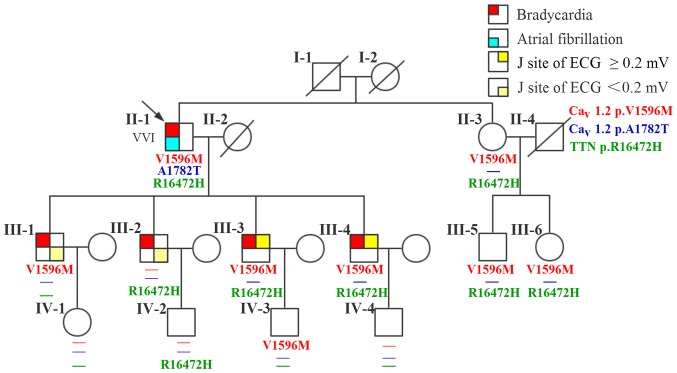

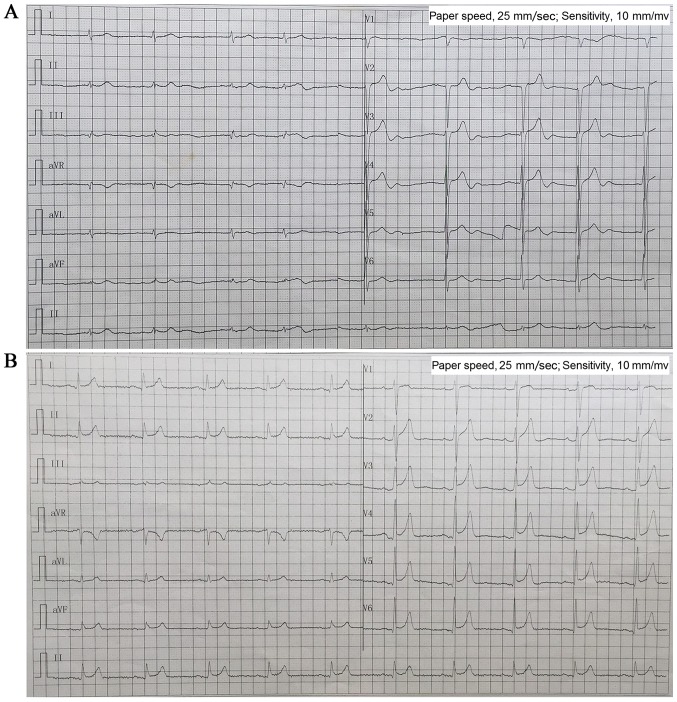

There are 20 members of the family, with 5 diseases (Fig. 1). A 76-year-old male (II-1; the proband) patient presented with a 40-year history of palpitation, chest tightness, and stress sweating and was repeatedly admitted to our hospital. The patient had an episode of syncope 8 years ago following progressive palpitation, fatigue, and dizziness. He received no treatment, although his ECG suggested bradycardia and atrial fibrillation. In 2013, a 24-h Holter ECG monitoring (Fig. 2A) confirmed bradycardia (average heart rate, 49 bpm; range, 29–89 bpm) and atrial fibrillation. The echocardiogram showed moderate mitral regurgitation, tricuspid regurgitation, and mild aortic valve regurgitation. He was diagnosed with SSS and received a permanent pacemaker implantation. The proband took no drugs such as digitalis, β-blocker, or calcium blocker to slow down his heart rate. Prior to the diagnosis, he had hypertension and an incidence of cerebral infarction. Evaluation of the family history revealed that all his four children (III-1, III-2, III-3, and III-4; all male) presented with bradycardia with an average heart rate <50 bpm; two of them (III-3 and III-4) showed early onset (since their childhood) of symptoms similar to their father's, and the other two (III-1 and III-2) have palpitation when they are tired or emotional swings. ECG (Fig. 2B) diagnosed III-3 and III-4 with ER syndrome (ST elevation in V1-V6 was upward concave, the J-point elevation ≥0.2 mV) and III-1 and III-2 with ER pattern (ST elevation in V4-6 was upward concave, the J-point elevation <0.2 mV).

Figure 1.

A pedigree, phenotype, and genotype of the family. Males and females are indicated by squares and circles, respectively. Proband is indicated by an arrow. Deceased individuals are indicated by diagonal lines. Phenotypes presented by the family members are depicted by a red top-left square for bradycardia; blue bottom-left square for atrial fibrillation; top-right square and bottom-right square (yellow) represent J-site of ECG ≥0.2 mV and <0.2 mV, respectively. VVI refers to the installation of pacemaker. ECG, 12-lead electrocardiogram.

Figure 2.

Electrocardiographic data. (A) Proband II-1 before installing pacemaker ECG showed bradycardia and atrial fibrillation (ventricular rate 50 bpm). (B) III-4 ECG showed sinus bradycardia (57 bpm) and early repolarization syndrome (ST elevation in V1-6 was upward concave, J-point elevation ≥0.2 mV). ECG, 12-lead electrocardiogram.

The proband's parents (I-1 and I-2) had passed away; his mother (I-2) reported symptoms of paroxysmal arrhythmia before her death, but the exact diagnosis was unknown. The proband's four grandchildren (IV-1, IV-2, IV-3, IV-4; aged 10–24 years) and younger sister (II-2) and her two children (III-5 and III-6) presented with no cardiac symptoms and all had normal ECG (Table I). No other cutaneous, retinal, neurologic, and somatic abnormalities were reported or observed in this family.

Table I.

Clinical data of the family members.

| ID | Age (years) | Sex | Onset age (years) | Symptoms | ECG/HOLTER | Echocardiogram |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| II-1a | 76 | Male | Twenties | Palpitation, chest tightness, stress sweating, emotional, and syncope | Bradycardia, atrial fibrillation | Mitral, tricuspid, and aortic valve regurgitation |

| II-3 | 73 | Female | Twenties | Palpitation, chest tightness, stress sweating | Normal | Normal |

| III-1 | 52 | Male | Twenties | Palpitation | Bradycardia, J-point elevation <0.2 mV | Normal |

| III-2 | 51 | Male | Twenties | Palpitation | Bradycardia, J-point elevation <0.2 mV | Normal |

| III-3 | 49 | Male | Twenties | Palpitation, chest tightness, stress sweating, and emotional | Bradycardia, J-point elevation ≥0.2 mV | Normal |

| III-4 | 43 | Male | Twenties | Palpitation, chest tightness, stress sweating, and emotional | Bradycardia, J-point elevation ≥0.2 mV | Normal |

| III-5 | 48 | Male | NA | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| III-6 | 44 | Female | NA | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| IV-1 | 23 | Female | NA | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| IV-2 | 22 | Male | NA | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| IV-3 | 21 | Male | NA | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| IV-4 | 9 | Male | NA | Normal | Normal | Normal |

Proband. NA, not available; ECG, 12-lead electrocardiogram.

Genetic analysis

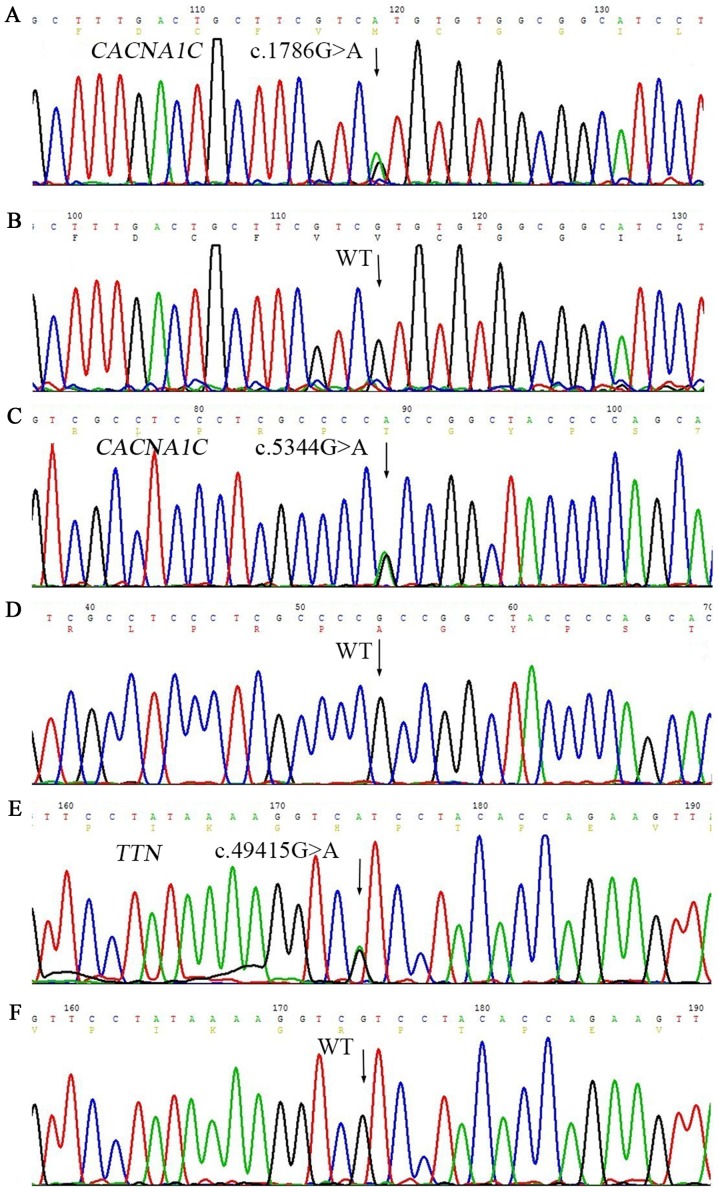

Twelve members in this family were enrolled into the genetic analysis study. First, we conducted a targeted exome sequencing on the proband for 61 genes, which are related with arrhythmia. The enriched and purified targeted regions were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencer (Illumina) for 90-bp reads; the mean read depth was 243X and >97% bases were >30X. A total of 123 variants (including point variant and insertion/deletion) were detected, and mutant polymorphism (SNP) loci greater than 1% were filtered out through 1000 Genomes MAF (population frequency information from 1000 genomes project). Values of dbSNP and the remaining nine variants were found in clinvar database, excluding synonymous and intron variants (out of exon over 2 bp), to obtain three variants (Table II). No rare nonsynonymous variants were found except heterozygous c.1786G>A (rs768034509) in CACNA1C, c.5344G>A (rs750078053) in CACNA1C, and c.49415G>A (rs561977468) in TTN, predicting valine to methionine substitution at the amino acid 596 (p. V596M) in CACNA1C (Fig. 3A), alanine to threonine substitution at the amino acid 1782 (p. A1782T) in CACNA1C (Fig. 3C), and arginine to histidine substitution at the amino acid 16472 (p. R16472H) in TTN (Fig. 3E). In addition, c.3979-8delC was present in the intron of MYH6, and c.68-5C>T was present in the intron region of TNNT2. Three synonymous variants were detected on TTN (p.Ala3897=p.Tyr6529=p.Gly12282) (Table II). These variants were in the non-coding region, suggestive of the absence of any effect of this family with sinus bradycardia on ER.

Table II.

Nine mutations found in Clinvar database of a propositus in a family with hereditary complex sinus bradycardia (MAF ≤0.01).

| Genes | RefSeq | Nucleic acid alternation | Amino acid alternation | Mutation location | Zygosity | Chr:location | RS-ID | MAF | Mutation type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CACNA1C | NM_001129843 | c.1786G>A | p.Val596Met | EX13 | Het | chr12:2676851 | rs768034509 | 0 | Missense |

| CACNA1C | NM_001129843 | c.5344G>A | p.Ala1782Thr | EX42 | Het | chr12:2788862 | rs750078053 | 0 | Missense |

| MYH6 | NM_002471 | c.3979-8delC | – | IN28 | Het | chr14:23858272 | rs193922652 | 0 | – |

| TNNC1 | NM_003280 | c.108C>A | p.Ile36Ile | EX3 | Het | chr3:52486216 | rs202000367 | 0.0027 | Synonymous |

| TNNT2 | NM_000364 | c.68-5C>T | – | IN4 | Het | chr1:201338978 | rs540630390 | 0 | – |

| TTN | NM_003319 | c.11691G>T | p.Ala3897Ala | EX45 | Het | chr2:179605180 | rs746578 | 0 | Synonymous |

| TTN | NM_003319 | c.19587C>T | p.Tyr6529Tyr | EX79 | Het | chr2:179483495 | rs397517587 | 0 | Synonymous |

| TTN | NM_003319 | c.36846C>A | p.Gly12282Gly | EX135 | Het | chr2:179451897 | – | 0 | Synonymous |

| TTN | NM_003319 | c.49415G>A | p.Arg16472His | EX154 | Het | chr2:179434249 | rs561977468 | 0 | Missense |

Removing the mutated sites of which the MAF was over 1% through dbSNP 1000 Genomes (population frequency information from the 1000 Genomes Project). CACNA1C, calcium voltage-gated channel subunit alpha1 C; TTN, titin.

Figure 3.

Genetic analysis revealed three novel heterozygous variations of CACNA1C and TTN gene in the family. (A) Missense variant c.1786G>A in CACNA1C gene. (C) Missense variant c.5344G>A in CACNA1C gene. (E) Missense variant c.49415G>A in TTN gene. The arrows indicate the comparison between the mutant site and normal wild-type. WT corresponds to (B), (D), and (F), respectively. CACNA1C, calcium voltage-gated channel subunit alpha1 C; TTN, titin; WT, wild-type.

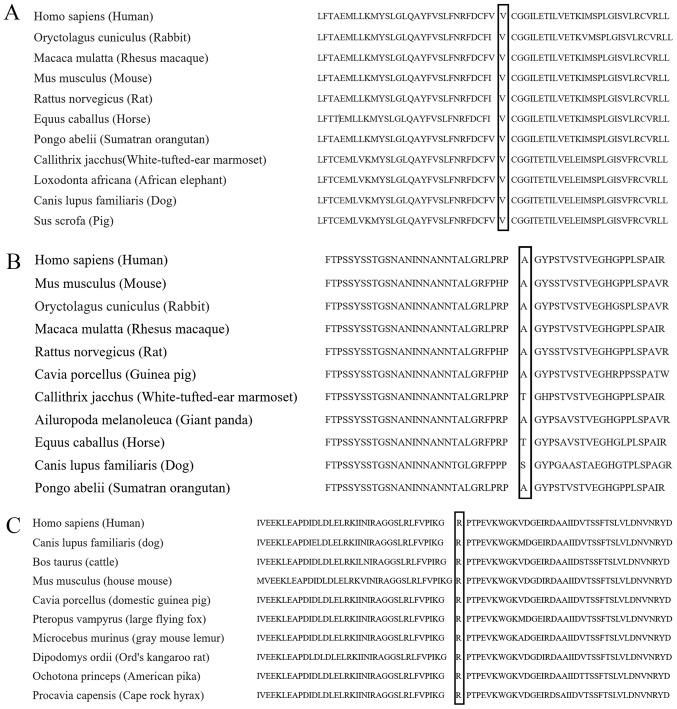

These three mutant sites (V596M and A1782T on CACNA1C and R16472H on TTN) are heterozygous variants. The frequency of the variant in 1000 genomes project was 0, while clinvar database had no relevant report at these sites (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/?term=CACNA1C [gene] and http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/?term=TTN [gene]). V596M variant in CACNA1C was predicted to be damaging with a score of 1.000 (sensitivity, 0.00; specificity, 1.00) by PolyPhen-2 software. The variant A1782T was predicted to be benign, with a score of 0.010 (sensitivity, 0.96; specificity, 0.77). We speculate that these two variants are likely to affect the function of CACNA1C-encoded ion channels. R16472H variant in TTN was predicted to be probably damaging with a score of 0.743 (sensitivity, 0.85; specificity, 0.92). These three variant sites are highly conserved among many species (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Amino acid alignment shows conservation among species of (A) valine ("V") at position l596 in CACNA1C, (B) alanine ("A") at position 1782 in CACNA1C (NP_001123315.1) and (C) arginine ("R") at position 16472 in TTN (NP_003310.4), respectively. CACNA1C, calcium voltage-gated channel subunit alpha1 C; TTN, titin.

Genetic analysis showed that none of the eleven family members carried c.5344G>A variant in CACNA1C gene. On the other hand, c.1786G>A in CACNA1C gene and c.49415G>A in TTN gene were detected in five family members, including the proband's two sons III-3 and III-4, and sister II-3 and her two children III-5 and III-6. Other six family members only had either of them.

Discussion

Cardiomyopathy and ion channel dysfunction are two major causes for inherited cardiac arrhythmias (20). In this study, we identified two novel missense variants in CACNA1C gene (calcium channel gene) and one novel missense variant in TTN gene (cardiomyocyte gene) in a family with symptomatic bradycardia, which eventually progressed into SSS in the proband.

CACNA1C gene encodes an alpha-1 subunit of a voltage-dependent calcium channel. I-caL plays a key role in the generation of spontaneous action potential in pacemaker (e.g., sinoatrial node) cells through the conduction of inward calcium currents. Any dysfunction in I-caL leads to significantly attenuated automaticity of these cells (21). Variants in CACNA1C gene have been associated with cardiac diseases such as Long-QT syndrome (22), Timothy syndrome (23), and Brugada syndrome (24). However, none has been reported in SSS. This is the first study to report missense variants of CACNA1C gene in patients with SSS. The two SNPs in CACNA1C gene detected in this family result in two amino acid replacements, localized at the third transmembrane segment of domain II (DIIS3) (p.596V>M) and carboxyl (C)-terminus (p.1782A>T) of CACNA1C, respectively. However, only p.596V>M variant was thought to be damaging, while p.1782A>T variant was neutral. Regardless, the proband was the only carrier of p.1782A>T variant; therefore, it is unlikely that this variant contributes to the inheritance of bradycardia and ER in the family. Although the proband is also the only one diagnosed with SSS, this diagnosis is unlikely to be associated with p.1782A>T variant but more of a reflection of his disease progression. A previous study showed that the expression of CACNA1C in the sinoatrial node decreases with aging (25); this observation may explain the deterioration of cardiac symptoms in the proband as he aged. It should be alerted that the cardiac symptoms displayed by the proband's sons may eventually develop into SSS. Furthermore, the proband's four sons exhibited ER, an ECG pattern that was unobserved in the proband. This observation may be due to different manifestations of the disease at different stages. We estimate that p.596V>M variant in CACNA1C may partly explain ER observed in the proband's three sons because CACNA1C gene has been identified as a susceptibility gene for ER syndrome (11).

A variant in the gene encoding for the SCN5A, c.2365G>A (p.789V>I), was a disease-causing missense variant for Brugada syndrome (26) and identified as a paralogue variant for CACNA1C variant c.1786G>A (p.596V>M). According to the Paralogue Annotation theory (www.cardiodb.org/paralogue_annotation/), known disease-causing paralogue variants (e.g., SCN5A variant c.2365G>A in this case) may be transferred to equivalent amino acids in the protein of interest (e.g., CACNA1C variant c.1786G>A in this case) to identify residues likely to be intolerant to the variation (27). Furthermore, CACNA1C variant c.1786 G allele, similar to SCN5A variant c.2365 G allele, may be intolerant to genetic variant; therefore, G>A variant at this position is very likely to induce arrhythmias.

The gene TTN encodes for titin (connectin), the largest known protein, which spans half of a sarcomere and plays critical roles in cardiac (and skeletal) muscle function. Mutations in TTN gene have been associated with cardiac diseases such as dilated cardiomyopathy (28), familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (29), early-onset myopathy with fatal cardiomyopathy (30), and proximal myopathy with early respiratory muscle involvement (31). The variant c.49415G>A in TTN gene detected in this family results in an amino acid replacement, which localizes at an immunoglobulin (Ig)-like and Fn3 domains super-repeat segment in the A-band region. This region was identified as a hot spot for inherited dilated cardiomyopathy, a major cause of heart failure and premature death (32); however, the study only included truncation mutations. The missense variant c.49415G>A (p.16472R>H) in this region is likely to be damaging, although it may not directly cause the malfunction of sinoatrial node. A recent study showed that patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy and variants in TTN gene were more likely to experience supraventricular arrhythmia such as atrial fibrillation than those without TTN variant (33). Likewise, the presence of TTN c.49415G>A variant may exacerbate cardiac symptoms accompanied by bradycardia in the proband (atrial fibrillation) and his two sons III3 and III4 (more severe ER).

Genetic mutations in genes encoding ankyrin-B (ANK2) (34), hyperpolarization-activated channel (HCN4) (35), and SCN5A (36) have been associated with sinoatrial dysfunction. However, we failed to observe any clinically meaningful variants in these genes. We cannot rule out genes that were not covered by our genetic analyses and the contribution of their variants to disease development. First, six family members carried both CACNA1C c.1786G>A and TTN c.49415G>A variants, but three of them (II3, III5, and III6) failed to show any cardiac symptoms observed in the proband and his two sons III3 and III4. Second, the proband's son III2 carried only TTN c.49415G>A variant, which is unlikely to cause bradycardia alone, but he showed symptoms of bradycardia. However, the discrepancies between phenotypes and genotypes are very common in genetics; for instance, phenotypes may not always manifest in all individuals carrying the same genetic variants (incomplete penetrance), and the type and severity of phenotypes vary between genotype-positive individuals (variable expressivity) (37). Factors such as age, sex, and nutrition may also contribute to different manifestations of genetic diseases. In rare diseases such as SSS, finding disease-causing variants by looking non-exhaustedly in a genome-wide range is almost impossible; hence, it is more realistic to focus on target genes to identify disease-causing variants based on the knowledge from databases and previous studies despite the limitation that the target gene list may always be incomplete.

In conclusion, our study suggests the involvement of the novel missense CACNA1C c.1786G>A and TTN c.49415G>A variants in the inheritance of symptomatic bradycardia and development of SSS. Future studies are required to understand the etiology at the molecular level.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Financial scheme for young talents training program of Fujian Health industry (grant no. 2015-ZQN-ZD-7) and the Science and Technology Project of Fujian Province (grant no. 2014Y0007), China.

References

- 1.Sanders P, Lau DH, Kalman JK. Sinus node abnormalities. In: Zipes D, Jalife J, editors. Cardiac Electrophysiology: From Cell to Bedside. 6th. Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia: 2014. pp. 691–696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semelka M, Gera J, Usman S. Sick sinus syndrome: A review. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:691–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mond HG, Proclemer A. The 11th world survey of cardiac pacing and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: Calendar year 2009-a World Society of Arrhythmia's project. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2011;34:1013–1027. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2011.03150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayashi M, Shimizu W, Albert CM. The spectrum of epidemiology underlying sudden cardiac death. Circ Res. 2015;116:1887–1906. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monfredi O, Boyett MR. Sick sinus syndrome and atrial fibrillation in older persons-A view from the sinoatrial nodal myocyte. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;83:88–100. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Platzer J, Engel J, Schrott-Fischer A, Stephan K, Bova S, Chen H, Zheng H, Striessnig J. Congenital deafness and sinoatrial node dysfunction in mice lacking class D L-type Ca2+ channels. Cell. 2000;102:89–97. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baig SM, Koschak A, Lieb A, Gebhart M, Dafinger C, Nürnberg G, Ali A, Ahmad I, Sinnegger-Brauns MJ, Brandt N, et al. Loss of Ca(v)1.3 (CACNA1D) function in a human channelopathy with bradycardia and congenital deafness. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:77–84. doi: 10.1038/nn.2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosso R, Kogan E, Belhassen B, Rozovski U, Scheinman MM, Zeltser D, Halkin A, Steinvil A, Heller K, Glikson M, et al. J-point elevation in survivors of primary ventricular fibrillation and matched control subjects: Incidence and clinical significance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derval N, Simpson CS, Birnie DH, Healey JS, Chauhan V, Champagne J, Gardner M, Sanatani S, Yee R, Skanes AC, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of early repolarization in the CASPER registry: Cardiac arrest survivors with preserved ejection fraction registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:722–728. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahida S, Derval N, Sacher F, Berte B, Yamashita S, Hooks DA, Denis A, Lim H, Amraoui S, Aljefairi N, et al. History and clinical significance of early repolarization syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burashnikov E, Pfeiffer R, Barajas-Martinez H, Delpón E, Hu D, Desai M, Borggrefe M, Häissaguerre M, Kanter R, Pollevick GD, et al. Mutations in the cardiac L-type calcium channel associated with inherited J-wave syndromes and sudden cardiac death. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1872–1882. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haïssaguerre M, Chatel S, Sacher F, Weerasooriya R, Probst V, Loussouarn G, Horlitz M, Liersch R, Schulze-Bahr E, Wilde A, et al. Ventricular fibrillation with prominent early repolarization associated with a rare variant of KCNJ8/KATP channel. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:93–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo Q, Ren L, Chen X, Hou C, Chu J, Pu J, Zhang S. A novel mutation in the SCN5A gene contributes to arrhythmogenic characteristics of early repolarization syndrome. Int J Mol Med. 2016;37:727–733. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haïssaguerre M, Derval N, Sacher F, Jesel L, Deisenhofer I, de Roy L, Pasquié JL, Nogami A, Babuty D, Yli-Mayry S, et al. Sudden cardiac arrest associated with early repolarization. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2016–2023. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gussak I, Antzelevith C. Early repolarization syndrome: Clinical characteristics and possible cellular and ionic mechanisms. J Electrocardiol. 2000;33:299–309. doi: 10.1054/jelc.2000.18106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He J, Wu J, Jiao Y, Wagner-Johnston N, Ambinder RF, Diaz LA, Jr, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N. IgH gene rearrangements as plasma biomarkers in Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma patients. Oncotarget. 2011;2:178–185. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu J, Matthaei H, Maitra A, Dal Molin M, Wood LD, Eshleman JR, Goggins M, Canto MI, Schulick RD, Edil BH, et al. Recurrent GNAS mutations define an unexpected pathway for pancreatic cyst development. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:92ra66. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu YB, Gan JH, Luo JW, Zheng XY, Wei SC, Hu D. Splicing mutation of a gene within the Duchenne muscular dystrophy family. Genet Mol Res. 2016 Jul 14;15 doi: 10.4238/gmr.15028258. doi: 10.4238/gmr.15028258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li R, Li Y, Kristiansen K, Wang J. SOAP: Short oligonucleotide alignment program. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:713–714. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mizusawa Y. Recent advances in genetic testing and counseling for inherited arrhythmias. J Arrhythm. 2016;32:389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.joa.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verheijck EE, van Ginneken AC, Wilders R, Bouman LN. Contribution of L-type Ca2+ current to electrical activity in sinoatrial nodal myocytes of rabbits. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H1064–H1077. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.3.H1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crotti L, Celano G, Dagradi F, Schwartz PJ. Congenital long QT syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:18. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Splawski I, Timothy KW, Sharpe LM, Decher N, Kumar P, Bloise R, Napolitano C, Schwartz PJ, Joseph RM, Condouris K, et al. Ca(V)1.2 calcium channel dysfunction causes a multisystem disorder including arrhythmia and autism. Cell. 2004;119:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antzelevitch C, Pollevick GD, Cordeiro JM, Casis O, Sanguinetti MC, Aizawa Y, Guerchicoff A, Pfeiffer R, Oliva A, Wollnik B, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the cardiac calcium channel underlie a new clinical entity characterized by ST-segment elevation, short QT intervals, and sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 2007;115:442–449. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.668392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones SA, Boyett MR, Lancaster MK. Declining into failure: The age-dependent loss of the L-type calcium channel within the sinoatrial node. Circulation. 2007;115:1183–1190. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.663070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kapplinger JD, Tester DJ, Alders M, Benito B, Berthet M, Brugada J, Brugada P, Fressart V, Guerchicoff A, Harris-Kerr C, et al. An international compendium of mutations in the SCN5A-encoded cardiac sodium channel in patients referred for Brugada syndrome genetic testing. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.09.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh R, Peters NS, Cook SA, Ware JS. Paralogue annotation identifies novel pathogenic variants in patients with Brugada syndrome and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. J Med Genet. 2014;51:35–44. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerull B, Gramlich M, Atherton J, McNabb M, Trombitás K, Sasse-Klaassen S, Seidman JG, Seidman C, Granzier H, Labeit S, et al. Mutations of TTN, encoding the giant muscle filament titin, cause familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat Genet. 2002;30:201–204. doi: 10.1038/ng815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Satoh M, Takahashi M, Sakamoto T, Hiroe M, Marumo F, Kimura A. Structural analysis of the titin gene in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Identification of a novel disease gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;262:411–417. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carmignac V, Salih MA, Quijano-Roy S, Marchand S, Al Rayess MM, Mukhtar MM, Urtizberea JA, Labeit S, Guicheney P, Leturcq F, et al. C-terminal titin deletions cause a novel early-onset myopathy with fatal cardiomyopathy. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:340–351. doi: 10.1002/ana.21089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicolao P, Xiang F, Gunnarsson LG, Giometto B, Edström L, Anvret M, Zhang Z. Autosomal dominant myopathy with proximal weakness and early respiratory muscle involvement maps to chromosome 2q. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:788–792. doi: 10.1086/302281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herman DS, Lam L, Taylor MR, Wang L, Teekakirikul P, Christodoulou D, Conner L, DePalma SR, McDonough B, Sparks E, et al. Truncations of titin causing dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:619–628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brun F, Barnes CV, Sinagra G, Slavov D, Barbati G, Zhu X, Graw SL, Spezzacatene A, Pinamonti B, Merlo M, et al. Titin and desmosomal genes in the natural history of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. J Med Genet. 2014;51:669–676. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohler PJ, Splawski I, Napolitano C, Bottelli G, Sharpe L, Timothy K, Priori SG, Keating MT, Bennett V. A cardiac arrhythmia syndrome caused by loss of ankyrin-B function; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2004; pp. 9137–9142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nof E, Luria D, Brass D, Marek D, Lahat H, Reznik-Wolf H, Pras E, Dascal N, Eldar M, Glikson M. Point mutation in the HCN4 cardiac ion channel pore affecting synthesis, trafficking, and functional expression is associated with familial asymptomatic sinus bradycardia. Circulation. 2007;116:463–470. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benson DW, Wang DW, Dyment M, Knilans TK, Fish FA, Strieper MJ, Rhodes TH, George AL., Jr Congenital sick sinus syndrome caused by recessive mutations in the cardiac sodium channel gene (SCN5A) J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1019–1028. doi: 10.1172/JCI200318062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giudicessi JR, Ackerman MJ. Determinants of incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity in heritable cardiac arrhythmia syndromes. Transl Res. 2013;161:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]