Abstract.

Laboratory diagnosis of toxocariasis is still a challenge especially in developing endemic countries with polyparasitism. In this study, three Toxocara canis recombinant antigens, rTES-26, rTES-30, and rTES-120, were expressed and used to prepare lateral flow immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) dipsticks. The concordance of the results of the rapid test (comprising three dipsticks) with a commercial IgG-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Cypress Diagnostics, Belgium) was compared against the concordance of two other commercial IgG-ELISA kits (Bordier, Switzerland and NovaTec, Germany) with the Cypress kit. Using Toxocara-positive samples, the concordance of the dipstick dotted with rTES-26, rTES-30, and rTES-120 was 41.4% (12/29), 51.7% (15/29), and 72.4% (21/29), respectively. When positivity with any dipstick was considered as an overall positive rapid test result, the concordance with the Cypress kit was 93% (27/29). Meanwhile, when compared with the results of the Cypress kit, the concordance of IgG-ELISA from NovaTec and Bordier was 100% (29/29) and 89.7% (26/29), respectively. Specific IgG4 has been recognized as a marker of active infection for several helminthic diseases; therefore, the two non-concordant results of the rapid test when compared with the NovaTec IgG-ELISA kit may be from samples of people with non-active infection. All the three dipsticks showed 100% (50/50) concordance with the Cypress kit when tested with serum from individuals who were healthy and with other infections. In conclusion, the lateral flow rapid test is potentially a good, fast, and easy test for toxocariasis. Next, further validation studies and development of a test with the three antigens in one dipstick will be performed.

INTRODUCTION

Human toxocariasis is a helminthic disease caused by larval stages from Toxocara canis and Toxocara cati, the roundworms of dogs and cats, respectively. The clinical picture can vary from asymptomatic to severe manifestations and depend on the pathway of migrating larvae in the affected tissue, the frequency of re-infection, and the inflammatory immune response.1

Human toxocariasis has a worldwide distribution and its reported incidence is higher in tropical and subtropical regions, especially in areas with poor sanitation and where the population of non-dewormed pets is high.2 Although it is considered one of the five main neglected parasitic infections by the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, USA, it is still not widely recognized as a major public health concern.3 The scarcity of reports on the prevalence of human toxocariasis and the unsatisfactory specificity of the diagnostic tests available for it, probably account for this lack of recognition.4 Thus, the true incidence and global importance of toxocariasis is probably underestimated.5

The importance of reliable tools for use in the diagnosis and epidemiology of toxocariasis cannot be over-stressed, and access to a rapid and accurate test that can be used for these purposes is highly desirable. Data from epidemiology studies will enable improvements to the health of populations through the implementations of better preventive measures to reduce or eliminate human Toxocara infections. Because Toxocara larval development is arrested in humans, eggs or larvae are not found in human feces. Hence, a definitive diagnosis of human toxocariasis is obtained by locating the larvae in infected tissue; however, this approach is not practical, is time consuming, and is difficult to perform.4,6 Therefore, the diagnosis of toxocariasis in an individual is usually based on clinical findings and positive serology results.

Commercial indirect immunoglobulin G (IgG)-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits are the most common serological tests used in many laboratories for diagnosing toxocariasis. Usually, these tests use Toxocara excretory-secretory (TES) antigens to detect IgG antibodies, but the antigen production is laborious, time-consuming, and with limited yield. A major disadvantage of using TES antigens is the inaccuracy of the test results generated by them, which is related to potential cross-reactivity with other parasitic nematodes, especially in tropical countries where infection with soil-transmitted helminths is common.6–8 Thus, identifying alternative antigens to replace native TES antigens for the serodiagnosis of human toxocariasis is a worthwhile endeavor. Furthermore, detection of IgG antibodies may be attributed to previous infection or exposure to the parasite, and not to an active infection.9,10

We have previously reported on an IgG4-ELISA based on three recombinant antigens (rTES-26, rTES-30, and rTES-120), which showed promising results.6 However, the yields and purities of the recombinant proteins were not satisfactory for use in rapid test development. Thus, the aim of the present study was to develop IgG4-lateral flow dipsticks for the detection of human toxocariasis following improvements to the yields and purities of the same three recombinant antigens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Serum samples.

A total of 79 serum samples were used; they comprised 29 serum samples from patients previously diagnosed as having toxocariasis based on clinical presentations and positive Toxocara serology using a commercial IgG-ELISA kit (Cypress Diagnostics, Belgium); 40 serum samples from healthy individuals and 10 serum samples from patients with other infections, namely, ascariasis (N = 2), strongyloidiasis (N = 2), ancylostomiasis (N = 2), leishmaniasis (N = 1), cysticercosis (N = 1), hydatidosis (N = 1), and schistosomiasis (N = 1). The latter two groups were negative by the same Toxocara commercial kit. These were anonymized samples from a serum bank at the Institute for Research in Molecular Medicine. The use of banked serum samples for evaluation of the diagnostic performance of laboratory tests was approved by the Universiti Sains Malaysia Research Ethics Committee.

Testing serum samples with commercial IgG-ELISA kits.

The concordance of the IgG4-lateral flow rapid test we developed in this study was compared with the commercial Cypress kit, and the concordance of two other IgG-ELISA kits was also compared with the Cypress kit. The kits included an ELISA kit based on native TES antigens (Bordier Affinity Products SA, Switzerland) and an ELISA based on synthetic glycopeptides (NovaTec Immunodiagnostica GmbH, Dietzenbach, Germany).

Recombinant protein expression and purification.

The DNA coding sequences for TES-26, TES-30, and TES-120 genes (Accession numbers U29761, AB009305, and U39815, respectively) were obtained as previously described,6 but with the following modifications: the signal peptide was omitted and the sequences were codon-optimized for expression in an Escherichia coli host system. These sequences were custom-cloned (ProteoGenix, France) into the pET32 expression vector (Novagen, Madison, WI). Upon receipt of the custom-cloned plasmids, for each plasmid, 2 μL was transformed into E. coli strain C41 (DE3) (Lucigen, Middleton, WI) using the heat-shock method.11

A starter culture for protein expression was prepared by selecting a single recombinant bacterial colony from an overnight subcultured plate and inoculating it into a 250 mL flask containing 100 mL of Terrrific Broth (TB) supplemented with 100 µg/mL of ampicillin. The culture was grown in an incubator shaker for 16 hours at 37°C, 200 rpm. A 10 mL volume of the starter culture was added into a 1-L flask containing 500 mL of TB supplemented with 100 µg/mL of ampicillin. The culture was incubated at 37°C, 200 rpm until the OD600 reached 0.4 or 0.5, followed by addition of 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside to induce expression of the recombinant protein. The induced culture was incubated at 30°C, 200 rpm for up to 6 hours.

The cells were centrifuged (10,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C), and the pellet was collected and resuspended in ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0), containing cOmplete™ Mini ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) (one tablet per 10 mL lysis buffer) and lysozyme (Amresco, Solon, OH) at 0.5 mg/mL. The cell suspension was incubated (4°C for 30 minutes) on a low speed rotator and then homogenized using a French press (Glen Mills Inc., Clifton, NJ) at a pressure of 1,700 psi. The lysed cells were centrifuged (10,000 × g, 10 minutes at 4°C), the resultant supernatant was transferred to a clean tube, mixed with DNase I solution (0.5 µg/mL), and then incubated on ice for 15 minutes. The cell mixture was recentrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C. The final supernatant was filtered through a 0.2 µm filter membrane and then used for protein purification.

Nitrilotriacetic acid resin (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) was used to purify the recombinant proteins. The filtered supernatant from the cell lysate was loaded onto the resin containing column at a ratio of 1:10 resin to lysate. The mixture was incubated with slow rotation at 4°C for 30 minutes. The column was assembled on a retort stand, and the bottom stopper was removed to allow the lysate to flow out of the column. A gradient of wash buffers (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10–100 mM imidazole, pH 8.0) were then added to remove any unbound contaminant proteins, thereby retaining the target protein on the resin. The target protein was eluted with elution buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, pH 8.0) and collected in 1 mL fractions per tube, up to 15 fractions in total. The fractions were analyzed by using sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and the gel was stained with Coomassie Blue. Fractions containing high purity proteins were pooled, concentrated, and buffer-exchanged into phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.2 using Vivaspin column (10,000 kDa molecular weight cut-off) (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). The concentrated protein was quantified using an RC DC protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

MALDI TOF/TOF analysis of the recombinant protein.

The target protein band was excised from the gel after SDS-PAGE separation and analyzed matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight/time of flight (MALDI TOF/TOF) according to the method described previously.12 Briefly, the protein band was destained in a solution containing 50% (v/v) acetonitrile (ACN) and 50% (v/v) 25 mM NH4HCO3 at 37°C for 30 minutes. The gel piece was reduced with 10 mM dithiothreitol (60°C for 30 minutes), followed by alkylation with 55 mM iodoacetamide in the dark at room temperature for 60 minutes. The gel piece was digested with 12.5 ng/μL of trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) at 37°C for 16 hours. The digested peptides were transferred to a fresh tube and the gel was further extracted using 50% (v/v) ACN, 49.9% (v/v) H2O, and 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). The sample was concentrated until it reached half of its original volume using a vacuum concentrator and then desalted using ZipTip C18 Pipette tips (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The peptides were mixed with the CHCA matrix solution (α-cyano-4-hydroxy-cinnamic acid, 10.0 mg/mL, in 50% [v/v] ACN and 0.1% [v/v] TFA). A 0.6 μL volume of the mixture per sample was then spotted on a MALDI plate and air-dried, and the sample was analyzed using a MALDI TOF/TOF 5800 mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA). The results were analyzed using the MASCOT search engine version 2.3.0213 against the whole Swiss-Prot database and/or the Toxocara-specific database from Swiss-Prot with 100 ppm and ±0.2 Da set for the peptide mass tolerance and fragment mass tolerance, respectively.

Western blotting recombinant proteins.

The purified recombinant proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE at a constant voltage of 100 V until the dye front reached the bottom of the gel. This was followed by protein transfer using the Trans-Blot Semi-Dry system (Bio-Rad) at a constant voltage of 12 V for 30 minutes. The membrane was cut into strips, and the strips that contained the unstained protein standard, or the protein sample for histidine detection, were blocked overnight in Superblock solution (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). The remaining strips, which were blocked for 1 hour followed by three washes at 5-minutes intervals with TBST (10 mM Tris-Cl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20), were then incubated overnight at 4°C with the individual serum samples as the primary antibodies at 1:100 in TBST. The serum samples used were from patients with toxocariasis (N = 4), healthy individuals (N = 2), and patients with ascariasis and strongyloidiasis (N = 2).

Next day, the membrane strips were washed three times at 5-minute intervals with TBST. They were incubated with anti-human IgG4-HRP conjugate (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at dilution of 1:1,000, and the strip containing the unstained protein standard was probed with Precision Protein StrepTactin-HRP conjugate (Bio-Rad) at a dilution of 1:10,000, whereas the strip with the protein sample for histidine detection was incubated with the His•Tag Antibody HRP conjugate (Novagen) at a dilution of 1:1,000 for 1 hour. After a final washing step, signal detection was performed using enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Thermo Scientific) and CL-XPosure film (Thermo Scientific).

Development of the lateral flow dipstick test.

Conjugation of monoclonal mouse anti-human IgG4 to colloidal gold nanoparticles.

Colloidal gold nanoparticles at an optical density (OD) of 1.0 were prepared using the seeding growth method previously described by Makhsin et al.14 Briefly, an optimum amount of anti-human IgG4 antibody (pH 6) was added to 10 mL of gold nanoparticles. This optimum amount was obtained by observing the lowest amount of antibody that did not change color after the addition of 10% (v/v) NaCl. The antibody-gold nanoparticle solution was mixed gently and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature followed by the addition of 1% (v/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO). The solution was centrifuged (7,400 × g, 10 minutes) and the pellet was resuspended in 1% (v/v) BSA. After recentrifugation, the final pellet was resuspended in 1% (v/v) BSA at a final volume of 300 μL. The OD of the IgG4-gold conjugate was measured using a UV-VIS-NIR spectrophotometer (UV-3600; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) and then stored at 4°C.

Preparation of the lateral flow dipstick.

A Hi-Flow Plus 90 membrane card and cellulose fiber absorbent pad, both from Millipore Corporation (Bedford, MA) were used to prepare the lateral flow dipstick. The absorbent pad was placed on the sticky part of the nitrocellulose membrane with an approximate 2 mm overlap between the pad and the nitrocellulose membrane surface. The assembled card was then cut into dipstick strips (5 mm width) using a strip cutter (A-Point Technologies Inc., Gibbstown, NJ). A 1 µL volume of purified recombinant protein was dotted onto the middle of each strip, the strips were dried in a 37°C incubator for 2 hours, blocked with a blocking solution (Roche Diagnostics), and then placed overnight in a 37°C incubator. The next day, the strips were transferred to a dry cabinet (< 20% humidity) at room temperature for storage.

Optimization of the antigen concentration and the OD for the anti-human IgG4 colloidal gold conjugate.

The dipsticks were dotted with five different antigen concentrations (i.e., 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, and 3.5 mg/mL) with an initial OD of 8 to select an antigen concentration that detects toxocariasis positive serum samples, but not negative samples. The dipstick with the selected antigen concentration was then tested with various ODs of the conjugated antibody from OD 5 to 10.

Lateral flow dipstick test procedure.

Ten microliters of each serum sample was diluted (1:2) with Chase buffer (Reszon Diagnostics International, Malaysia) and placed in the first well of a microtiter plate. Gold conjugated IgG4 antibody (25 µL) was added to the second well, and 35 µL of Chase buffer was pipetted into the third well. The dipstick was placed in the first well, and the serum sample was allowed to migrate up the membrane by capillary action. Once the sample reached the top of the nitrocellulose membrane, the dipstick was transferred to the second well containing the IgG4-gold conjugate. The dipstick was left in the well until all the conjugate was absorbed, and then transferred to the third well containing the Chase buffer to remove the excess unbound conjugate. The result was read once the background became clear, which took less than 15 minutes. The test was interpreted as positive when a red colored dot appeared in the test dot region. If the test dot region remained clear (with no red colored dot seen), the test was considered negative.

RESULTS

Expression, purification, and confirmation of recombinant protein identity.

Post-expression induction incubation periods of 3, 4, and 5 hours for rTES-26, rTES-30, and rTES-120, respectively, each produced satisfactory amounts of soluble protein (∼2 mg/L of culture). The rTES-26, rTES-30, and rTES-120 target protein bands appeared on the SDS-PAGE gel at approximate molecular masses of 40, 36, and 40 kDa, respectively (Figure 1). The MALDI TOF/TOF analysis confirmed the identities of the three recombinant protein bands: rTES-26 (UniProt Accession number: P54190) had a protein score of 232 (cutoff value > 70), four matched peptides, and 29% sequence coverage; rTES-30 (UniProt Accession number: O76131) had a protein score of 180, three matched peptides, and 19% sequence coverage; and rTES-120 (UniProt Accession number: Q26882) had a protein score of 134, one unique peptide match, and 17% sequence coverage.

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE of purified rTES-26, rTES-30, and rTES-120 proteins. Lane 1: rTES-26 protein (∼40 kDa); lane 2: rTES-30 protein (∼36 kDa); rTES-120 (∼40 kDa). Arrows indicate the protein bands. SDS-PAGE = sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Western blot analysis of rTES-26, rTES-30, and rTES-120 proteins.

Western blot results are shown in Figure 2. All three recombinant proteins showed good reactivity when tested with serum samples from toxocariasis patients (lanes 1–4) with presence of band corresponding to the expected molecular mass of each protein. Meanwhile, incubation with negative serum samples that is, samples from healthy individuals and patients with other infections showed no such band on the blots (lanes 5–8). Presence of the histidine-fusion protein for each antigen was confirmed with the presence of band at the expected molecular mass when incubated with anti-His-HRP antibody (lane 9).

Figure 2.

IgG4-western blots of recombinant proteins probed with various serum samples (A) rTES-26 protein; (B) rTES-30 protein; (C) rTES-120 protein. Lanes 1–4: individual serum samples from patients with toxocariasis; lanes 5 and 6: serum samples from healthy individuals; lanes 7 and 8: serum samples from patient with other infections; lane 9: protein probed with anti-histidine-HRP. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Optimization results for the dipsticks.

The optimum antigen concentration dotted onto the dipsticks for rTES-26, rTES-30, and rTES-120 was 3.0, 2.5, and 3.0 mg/mL, respectively, and the optimal OD of the anti-human IgG4 gold conjugate antibody was OD 9, 8, and 9 for rTES-26, rTES-30, and rTES-120, respectively. Under these conditions, all the toxocariasis samples tested with the dipsticks gave positive results, whereas all the negative samples showed negative results.

Concordance of the lateral flow dipstick test for the recombinant antigens with the Cypress kit.

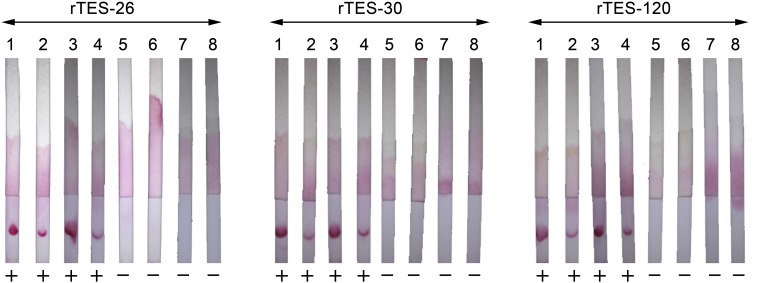

Table 1 summarizes the concordance of the results of the lateral flow dipsticks with the Cypress kit, as compared with the concordance of two other commercial IgG-ELISA kits with the Cypress kit. The results showed that using the Toxocara-positive samples, the concordance of the individual dipsticks using rTES-26, rTES-30, and rTES-120 was 41.4%, 51.7%, and 72.4%, respectively. When the positivity of any dipstick was considered to be a positive rapid test result (i.e., using the results of the “combined” tests), the overall concordance with the Cypress kit was 93.1%. By comparison, the concordance of the IgG-ELISA kits from NovaTec and Bordier with the Cypress kit was 100% (29/29) and 89.7% (26/29), respectively. Thus, using the Toxocara-positive serum samples, the concordance of the rapid test (based on “combined” results) with the Cypress kit was higher in comparison with the Bordier kit that uses native TES antigens, but lower than the NovaTec kit, which uses a synthetic antigen. Using the Toxocara-negative serum samples, the concordance of each of the three dipsticks with the Cypress kit was 100%. Figure 3 shows representative images of the results obtained using dipsticks dotted with rTES-26, rTES-30, and rTES-120.

Table 1.

Concordance results of IgG4-lateral flow dipsticks dotted with rTES-26, rTES-30, and rTES-120 with Cypress IgG- ELISA kit, as compared with the concordance of two other commercial IgG-ELISA kits with the Cypress kit

| Assay | Antigen | Antibody detector | Number of samples* (N = 29) | Concordance (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||||

| Lateral flow dipstick | rTES-26 | IgG4 | 12 | 17 | 41.4 |

| rTES-30 | 15 | 14 | 51.7 | ||

| rTES-120 | 21 | 8 | 72.4 | ||

| “Combined”† | 27 | 2 | 93.1 | ||

| ELISA (Bordier) | Native | IgG | 26 | 3 | 89.7 |

| ELISA (NovaTec) | Synthetic | 29 | 0 | 100 | |

ELISA = enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IgG = immunoglobulin G.

Serum samples from patients previously diagnosed as having toxocariasis based on clinical presentation and positive Toxocara serology using Cypress IgG-ELISA kit.

“Combined” refers to positive result obtained with any of the three dipsticks.

Figure 3.

Representative lateral flow dipsticks dotted with rTES-26, rTES-30, and rTES-120 when tested with various serum samples. Strips 1–4 show positive results with samples from patients with toxocariasis; strips 5 and 6 show negative dipstick results with samples from healthy individuals; strips 7 and 8 show negative dipstick results with samples from patients with other infections. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

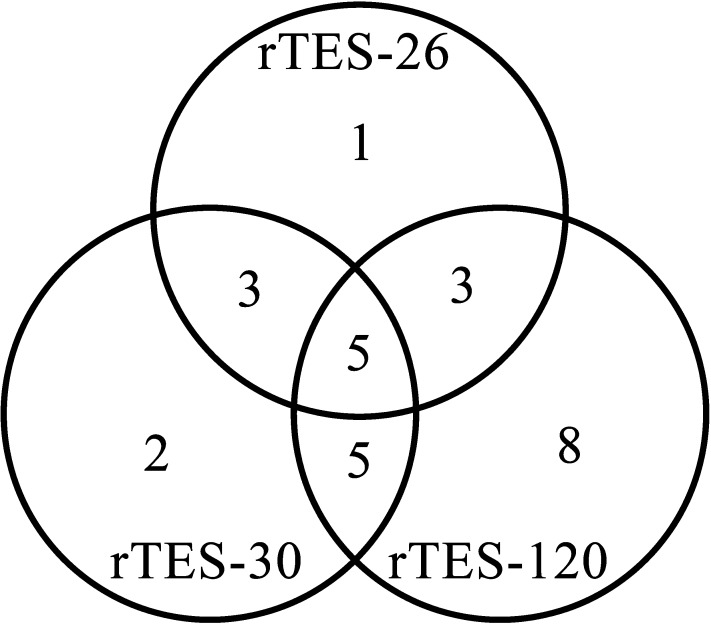

The Venn diagram (Figure 4) shows an overview of the number of positive results of the dipsticks, when tested with toxocariasis patients’ serum samples. The diagram showed 11 serum samples uniquely detected by each dipstick, five samples detected by all the dipsticks, and 11 samples detected by at least two dipsticks.

Figure 4.

Venn diagram illustrating the distribution of the positive results obtained with the dipsticks dotted with rTES-26, rTES-30, and rTES-120, when tested with Toxocara-positive serum samples.

DISCUSSION

Indirect IgG-based ELISA is used widely for diagnosing human toxocariasis, despite its reported low specificity and its potential to detect previous Toxocara infection. The lack of better performing and more suitable tests for diagnostic purposes has led to this situation. Jacquier et al.15 reported that the IgG-ELISA kit has a specificity and sensitivity of 86% and 91%, respectively. This assay gives false-positive reactions with non–T. canis helminthic infections that are commonly found in tropical settings.16 Many studies have shown that native TES cross-reacts with serum samples from patients with ascariasis, trichinellosis, fascioliasis, filariasis, strongyloidiasis, schistosomiasis, and gnathostomiasis, when tested by either IgG-ELISAs or IgG-western blots.8,10,16–20 To reduce this cross-reactivity, pre-absorption of serum samples with an extract of non-homologous parasites such as Ascaris suum has been proposed.17 But this extra step is rather cumbersome to perform21 and reduces the diagnostic sensitivity.22 In addition, the production of native TES antigens is laborious and time-consuming, and the protein yield is limited because of the difficulty involved in obtaining adult worms for cultivation of T. canis larvae.

Despite the availability of commercial IgG-ELISAs and western blots, there is still a need for a rapid diagnosis kit for toxocariasis, particularly one based on the lateral flow format, which is well-suited to point-of-care tests. ELISA and western blot methods require laboratory facilities, skilled personnel, and for economic reasons, several samples are usually collected before the tests are performed because each run of the assay requires several control wells or strips. Because toxocariasis is prevalent in low-resource areas, a lateral flow test is very useful for the following reasons: it is easy and quick to perform, it does not require a laboratory facility, it is transportable at room temperature, making it deliverable to under-developed areas, and it can be sold in small units per kit, thereby allowing even a single sample to be tested promptly. Furthermore, it can be made into a highly sensitive, specific, robust, and affordable test. These factors, in essence, are the “ASSURED” criteria set out by the World Health Organization to decide if a test addresses disease control needs.23

Several groups of investigators have developed rapid and portable field detection tests for diagnosing human toxocariasis. Akao et al.24 were the first group to develop a rapid test based on the direct flow-through principle (called ToxocaraCHEK) for serodiagnosis of Toxocara infection. Bojanich et al.25 developed a dot-test ELISA and suggested that the several advantages it offered when compared with standard ELISA (i.e., test stability, low cost, and ease of use without the need for specialized equipment) made it the most suitable assay for epidemiological surveillance studies. More recently, Lim et al.26 reported on the development and evaluation of a lateral flow rapid test based on rTES-30, which they called iToxocara. In the present study, three recombinant proteins, rTES-26, rTES-30, and rTES-120, were used for the development of lateral flow dipsticks. These recombinant antigens, produced by different recombinant plasmids, were previously reported by our group to be useful for toxocariasis diagnosis using IgG4-ELISA;6 however, we had noticed that the recombinant proteins were of insufficient purity and yield for use in rapid test development. This test format requires a high concentration of recombinant antigen (usually ≥ 1 mg/mL), or false negative results may occur if the antigen concentration is insufficient and false positive results may occur if the antigen purity is insufficient.

Thus, in the present study, modifications were made in the production of the three proteins from what we reported previously.6 These modifications, which included removing the signal peptide sequence, gene codon-optimization, and using a different expression vector, resulted in ∼2.0 mg of each protein per liter of bacterial culture. In addition, more stringent washing conditions were used in the affinity purification, thus resulting in antigens with greater purities. The IgG4-western blotting results using serum samples from toxocariasis patients, healthy individuals, and patients with other infections, showed that the three recombinant antigens were detected with good sensitivity and specificity.

Subsequently, the recombinant proteins were used to develop the IgG4 lateral flow test in a dot dipstick format. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing the development of such a test for detection of human toxocariasis. The IgG lateral flow rapid test reported by Lim et al.23 had a diagnostic sensitivity of 85.7% and a specificity of 90.1% when compared with IgG-ELISA, and both used rTES-30. In the present study, although the concordance of the individual dipsticks with the Cypress kit was not high (72%, 52%, and 41% for rTES-120, rTES-30, and rTES-26, respectively) when tested with Toxocara-positive serum samples, the combined results of all three dipstick tests were highly concordant (93%, 27/29) with the Cypress kit, a finding well-depicted in the Venn diagram. This result is in agreement with our previous study, which reported that a robust diagnostic assay should include the use of three recombinant antigens instead of a single antigen.6 The concordance of our assay was higher than that of the native TES antigen-containing Bordier kit, but lower than that of the NovaTec kit, which used a synthetic antigen. A possible reason for the two false negative results from the dipstick test when compared with the results of the NovaTec IgG-ELISA may involve to the use of different detectors in the two assays (i.e., IgG4 in the dipstick test and IgG in the ELISA test). Because specific IgG4 has been recognized as a marker of active infection in several parasitic diseases such as filariasis and onchocerciasis,27–31 it is possible that the seemingly false negative results of the dipstick test may have occurred because the samples were from patients with other cross-reactive infections or with a history of past Toxocara infections. The IgG response in humans against Toxocara infection may remain in the body for many years9 and, therefore, IgG-ELISA may not be able to distinguish between a past and an active infection.10 The diagnostic specificity of the developed rapid test was high because there was no cross-reactivity with serum samples from healthy individuals and other infections.

The limitation of this study is the low number of serum samples tested; thus further evaluation studies in multicenters are necessary to validate the diagnostic value of the rapid test. Other than using a much higher number of serum samples from various categories of individuals, testing with samples from post-treatment patients would be important to determine how long the test remains positive after therapy. It is also important to develop a dipstick in which all the three antigens can be dotted or lined on the same strip, perhaps by making a cocktail of the antigens. Furthermore, placing the dipstick in a cassette holder would make the test more robust for field use.

CONCLUSION

The IgG4-based rapid test using rTES-26, rTES-30, and rTES-120 showed good potential to be further developed as a point-of-care rapid test. This will make the test easily accessible to more people in the endemic regions, leading to better patient diagnosis and epidemiological data on toxocariasis.

Acknowledgments:

We thank Sandra Cheesman, PhD, from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Disclosures: Rahmah Noordin is named as the principal inventor of a granted patent on the use of rTES-26 for diagnosis of toxocariasis, entitled “Recombinant antigen for detection of toxocariasis.”

REFERENCES

- 1.Pawlowski Z, 2001. Toxocariasis in humans: clinical expression and treatment dilemma. J Helminthol 75: 299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glickman LT, Schantz PM, 1981. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of zoonotic toxocariasis. Epidemiol Rev 3: 230–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fialho PM, Correa CR, 2016. A systematic review of toxocariasis: a neglected but high-prevalence disease in Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg 94: 1193–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith H, Noordin R, 2006. Diagnostic limitations and future trends in the serodiagnosis of human toxocariasis. Holland C, Smith HV, eds. Toxocara: The Enigmatic Parasite Wallingford, United Kingdom: CABI Publishing, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hotez PJ, Wilkins PP, 2009. Toxocariasis: America’s most common neglected infection of poverty and a helminthiasis of global importance? PLoS Negl Trop Dis 3: e400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohamad S, Azmi NC, Noordin R, 2009. Development and evaluation of a sensitive and specific assay for diagnosis of human toxocariasis by use of three recombinant antigens (TES-26, TES-30USM, and TES-120). J Clin Microbiol 47: 1712–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamasaki H, Taib R, Watanabe Y-i, Mak JW, Zasmy N, Araki K, Chooi LPK, Kita K, Aoki T, 1998. Molecular characterization of a cDNA encoding an excretory–secretory antigen from Toxocara canis second stage larvae and its application to the immunodiagnosis of human toxocariasis1. Parasitol Int 47: 171–181. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith H, Holland C, Taylor M, Magnaval JF, Schantz P, Maizels R, 2009. How common is human toxocariasis? Towards standardizing our knowledge. Trends Parasitol 25: 182–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cypess RH, Karol MH, Zidian JL, Glickman LT, Gitlin D, 1977. Larva-specific antibodies in patients with visceral larva migrans. J Infect Dis 135: 633–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roldan WH, Espinoza YA, 2009. Evaluation of an enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot test for the confirmatory serodiagnosis of human toxocariasis. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 104: 411–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sambrook J, Russell DW, 2001. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saidin S, Yunus MH, Zakaria ND, Razak KA, Huat LB, Othman N, Noordin R, 2014. Production of recombinant Entamoeba histolytica pyruvate phosphate dikinase and its application in a lateral flow dipstick test for amoebic liver abscess. BMC Infect Dis 14: 182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13.Perkins DN, Pappin DJ, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS, 1999. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis 20: 3551–3567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makhsin SR, Razak KA, Noordin R, Zakaria ND, Chun TS, 2012. The effects of size and synthesis methods of gold nanoparticle-conjugated MalphaHIgG4 for use in an immunochromatographic strip test to detect brugian filariasis. Nanotechnology 23: 495719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacquier P, Gottstein B, Stingelin Y, Eckert J, 1991. Immunodiagnosis of toxocarosis in humans: evaluation of a new enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit. J Clin Microbiol 29: 1831–1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magnaval JF, Glickman LT, Dorchies P, Morassin B, 2001. Highlights of human toxocariasis. Korean J Parasitol 39: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camargo ED, Nakamura PM, Vaz AJ, da Silva MV, Chieffi PP, de Melo EO, 1992. Standardization of dot-ELISA for the serological diagnosis of toxocariasis and comparison of the assay with ELISA. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo 34: 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishida MM, Rubinsky-Elefant G, Ferreira AW, Hoshino-Shimizu S, Vaz AJ, 2003. Helminth antigens (Taenia solium, Taenia crassiceps, Toxocara canis, Schistosoma mansoni and Echinococcus granulosus) and cross-reactivities in human infections and immunized animals. Acta Trop 89: 73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magnaval JF, Fabre R, Maurieres P, Charlet JP, de Larrard B, 1991. Application of the western blotting procedure for the immunodiagnosis of human toxocariasis. Parasitol Res 77: 697–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noordin R, Smith HV, Mohamad S, Maizels RM, Fong MY, 2005. Comparison of IgG-ELISA and IgG4-ELISA for Toxocara serodiagnosis. Acta Trop 93: 57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fillaux J, Magnaval JF, 2013. Laboratory diagnosis of human toxocariasis. Vet Parasitol 193: 327–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhan B, et al. 2015. Identification of immunodominant antigens for the laboratory diagnosis of toxocariasis. Trop Med Int Health 20: 1787–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peeling RW, Holmes KK, Mabey D, Ronald A, 2006. Rapid tests for sexually transmitted infections (STIs): the way forward. Sex Transm Infect 82 (Suppl 5): v1–v6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akao N, Chu AE, Tsukidate S, Fujita K, 1997. A rapid and sensitive screening kit for the detection of anti-Toxocara larval ES antibodies. Parasitol Int 46: 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bojanich MV, Marino GL, López MÁ, Alonso JM, 2012. An evaluation of the dot-ELISA procedure as a diagnostic test in an area with a high prevalence of human Toxocara canis infection. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 107: 194–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim PK, Yamasaki H, Mak JW, Wong SF, Chong CW, Yap IK, Ambu S, Kumarasamy V, 2015. Field evaluation of a rapid diagnostic test to detect antibodies in human toxocariasis. Acta Trop 148: 32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwan-Lim GE, Forsyth KP, Maizels RM, 1990. Filarial-specific IgG4 response correlates with active Wuchereria bancrofti infection. J Immunol 145: 4298–4305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucius R, Kern A, Seeber F, Pogonka T, Willenbucher J, Taylor HR, Pinder M, Ghalib HW, Schulz-Key H, Soboslay P, 1992. Specific and sensitive IgG4 immunodiagnosis of onchocerciasis with a recombinant 33 kD Onchocerca volvulus protein (Ov33). Trop Med Parasitol 43: 139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egwang TG, Duong TH, Nguiri C, Ngari P, Everaere S, Richard-Lenoble D, Gbakima AA, Kombila M, 1994. Evaluation of Onchocerca volvulus-specific IgG4 subclass serology as an index of onchocerciasis transmission potential of three Gabonese villages. Clin Exp Immunol 98: 401–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weil GJ, Ogunrinade AF, Chandrashekar R, Kale OO, 1990. IgG4 subclass antibody serology for onchocerciasis. J Infect Dis 161: 549–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]