Abstract.

Prostatic involvement is common in men with melioidosis. Indeed, some clinicians recommend radiological screening of all male patients as an undrained prostatic abscess may result in relapse of this potentially fatal disease. However, sophisticated medical imaging is frequently unavailable in the remote and resource-poor locations where patients are managed. In this retrospective study from Queensland, Australia, 22/144 (15%) men with melioidosis had a radiologically confirmed prostatic abscess. The absence of urinary symptoms had a negative predictive value (NPV) (95% confidence interval [CI]) for prostatic abscess of 96% (90–99%), whereas a urinary leukocyte count of < 50 × 106/L had an NPV (95% CI) of 100% (94–100%). A simple clinical history and basic laboratory investigations appear to exclude significant prostatic involvement relatively reliably and might be used to identify patients in whom radiological evaluation of the prostate is unnecessary. This may be particularly helpful in locations where radiological support is limited.

Burkholderia pseudomallei, the environmental bacterium responsible for the disease melioidosis, is endemic in northern Australia and southeast Asia.1 Most infections are asymptomatic; however, overwhelming sepsis can develop rapidly, particularly in those with the classical risk factors of diabetes mellitus, hazardous alcohol use, chronic renal disease, chronic pulmonary disease, immunosuppression, and malignancy.2 In adults, pneumonia is the most frequent clinical manifestation, but prostatic abscess is also common, with 21% of male patients affected in one Australian series.3–5 Accordingly, many clinicians suggest that all men with systemic melioidosis should be screened for prostatic abscess as disease relapse is common without surgical drainage.1,3,4 A review of cases of melioidosis managed in our hospital since 1998 was performed to evaluate the appropriateness of this strategy.

Cairns Hospital is a 531-bed tertiary referral hospital servicing 280,000 people in Far North Queensland, Australia. All culture-confirmed cases of melioidosis between January 1, 1998 and June 30, 2017 were reviewed. Data were deidentified, entered into an electronic database (Microsoft Excel), and analyzed with statistical software (Stata 14). Groups were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test and the χ2 test where appropriate.

There were 176 men with culture-confirmed melioidosis during the study period; the presence of a prostatic abscess could be confirmed or excluded confidently in 144 (82%). These 144 patients were used in the analysis. A prostatic abscess was present in 22 (15%) patients, all of whom were adults (age > 18 years). The most frequent clinical risk factor for melioidosis in patients with a prostatic abscess was hazardous alcohol intake (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of male patients with melioidosis prostatic abscess and male patients with melioidosis without prostatic abscess

| Number | All | Men with prostatic abscess, N = 22 | Men without prostatic abscess, N = 122 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 144 | 54 (44-65) | 56 (46–64) | 54 (44–65) | 0.51 |

| Identifies as an ATSI | 144 | 67 (47%) | 12 (55%) | 55 (45%) | 0.49 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 142 | 76 (54%) | 9 (41%) | 67/120 (56%) | 0.2 |

| Hazardous alcohol intake* | 139 | 76 (55%) | 15/20 (75%) | 61/119 (52%) | 0.048 |

| Chronic kidney disease† | 142 | 26 (18%) | 2 (9%) | 24/120 (21%) | 0.22 |

| Chronic lung disease‡ | 141 | 24 (17%) | 2/21 (10%) | 22/120 (18%) | 0.32 |

| Immunosuppressio§ | 141 | 12 (9%) | 0/21 (0%) | 12/120 (10%) | 0.13 |

| Malignancy‖ | 141 | 14 (10%) | 2/21 (9%) | 12/120 (10%) | 0.95 |

| Urinary symptoms¶ | 134 | 40 (30%) | 18 (82%) | 22/112 (20%) | < 0.001 |

| Urine leukocytes > 50 × 106/L | 115 | 57 (50%) | 21/21 (100%) | 36/94 (38%) | < 0.001 |

| Urine erythrocytes > 50 × 106/L | 115 | 36/113 (32%) | 11/21 (52%) | 26/94 (28%) | 0.04 |

| Positive urine culture | 117 | 24 (21%) | 17/22 (77%) | 7/95 (7%) | < 0.001 |

| Bacteremia | 141 | 104 (74%) | 15 (68%) | 89/119 (75%) | 0.52 |

| Requiring ICU admission | 141 | 40/139 (29%) | 6/23 (26%) | 34/116 (29%) | 0.76 |

| Relapse# | 144 | 5 (3%) | 1 (5%) | 4 (3%) | 0.57 |

| Death** | 144 | 10 (7%) | 1 (5%) | 9 (7%) | 1 |

ATSI = Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander; ICU = intensive care unit. For age, the median and interquartile range is presented. For all other variables, the absolute number (percentage) is presented.

If documented in the medical record.

Serum creatinine ≥ 150 μmol/L documented before the presentation.

Receiving any ongoing treatment of a chronic lung condition.

Use of immunosuppressive agents, including corticosteroids, chemotherapy or immunomodulatory therapies.

Pathologically confirmed malignant neoplasm.

Dysuria, urgency, frequency, retention, or incontinence.

Clinical deterioration in association with a positive culture for Burkholderia pseudomallei.

Death due to melioidosis within 90 days of hospitalization.

Urinary symptoms (defined as dysuria, urgency, frequency, retention, or incontinence) were documented on admission in 18/22 (82%). The absence of urinary symptoms had a negative predictive value (NPV) (95% confidence interval [CI]) for prostatic abscess of 96% (90–99%) (Table 2). The results of digital rectal examination (DRE) were documented in 11/22 (50%), with prostatic tenderness present in only five (45%).

Table 2.

Diagnostic utility of tests to predict the presence of prostatic abscess in melioidosis

| Diagnostic utility | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Odds ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary symptoms | 82% (60–95%) | 79% (70–86) | 43% (28–59) | 96% (90–99) | 16.9 (5.2–54.5) |

| Urinary leukocytes > 50 × 106/L | 100% (84–100) | 62% (51–72) | 37% (24–51) | 100% (94–100) | Not calculable |

| Urinary erythrocytes > 50 × 106/L | 52% (30–74) | 72 (62–81) | 30 (16–47) | 87 (78–94) | 2.9 (1.1–7.6) |

| Bacteriuria | 77% (55–92) | 93% (85–97) | 71% (49–87) | 95% (88–98) | 42.7 (12.1–150.6) |

| Bacteremia | 68% (45–86) | 25% (18–34) | 14% (8–23) | 81% (65–92) | 0.7 (0.3–1.9) |

NPV = negative predictive value; PPV = positive predictive value. Gold standard: radiologically confirmed abscess. Presented as value (95% confidence interval).

Urinary microscopy results were available in 115 patients, including 21/22 with a prostatic abscess; all 21 had a urinary leukocyte count of ≥ 50 × 106/L. A urinary leukocyte count of < 50 × 106/L had an NPV (95% CI) for prostatic abscess of 100% (94–100%) (Table 2).

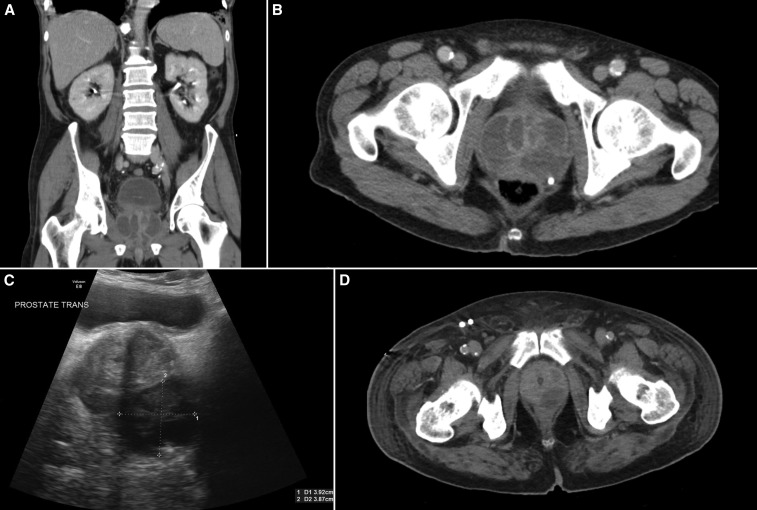

The diagnosis of a prostatic abscess was confirmed with computed tomography (CT) imaging alone in 16, ultrasound and confirmatory CT in three, and with ultrasound alone in three cases. One patient with dysuria and urinary leukocytes > 500 × 106/L had a negative CT on the day of hospitalization and a negative ultrasound 4 days later, but a follow-up CT on day 6 showed multiple prostatic abscesses. Prostatic abscesses were usually loculated, septated, and multilobar (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prostatic abscess due to melioidosis. (A and B) Coronal and axial computerized tomography shows an extensive, multiloculated abscess. (C) Pelvic ultrasonography showing a hypodense lesion consistent with prostatic abscess and (D) Axial computerized tomography of the prostate shows a left-sided loculated abscess.

All patients with a prostatic abscess received intravenous ceftazidime or meropenem. This was prescribed for a median (interquartile range, IQR) of 4.0 (2.0–4.5) weeks. All 21 patients who survived the intensive phase of intravenous treatment received an oral eradication therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for a median (IQR) of 12 (12–12) weeks. In the 20 patients in whom it could be determined, 19 (95%) commenced trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole during the first 2 weeks of their hospitalization.

Among the 22 patients with a prostatic abscess, 16 (73%) had surgical drainage, nine underwent transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)–guided drainage, six had transurethral deroofing of prostatic abscess, and one patient had a laparotomy to drain concomitant abscesses in the prostate, liver, and spleen. The remaining six patients were managed with antibiotics alone. In five this was due to small abscess size, although there was one patient with a 30 mm abscess who was offered surgery which he declined; fortunately, he was cured with antibiotic therapy alone. A repeat procedure was required in 3/9 (33%) of cases who had a TRUS-guided drainage but in no patients who had a transurethral approach.

Among the 22 patients with prostatic abscess, there was only one relapse. This was the result of inadequate source control; transurethral drainage was recommended, but the patient had concerns about fertility and agreed to only TRUS-guided drainage. He relapsed 3 months later, and transurethral drainage was performed without further complications. Only one of the patients with a prostatic abscess died; however, this was the result of multiorgan failure secondary to widely disseminated disease.

Melioidosis is a potentially fatal disease in which relapse is common without aggressive source control and prolonged antimicrobial therapy. A prostatic abscess was present in 15% of the men in this cohort, similar to a figure of 21% seen in another Australian series.5 This supports the contention that prostatic involvement should be strongly considered – and actively excluded – in all men with the disease. Routine radiological evaluation of men with melioidosis expedites recognition of prostatic involvement, permitting earlier definitive surgical management and reducing the risk of relapse.

However, routine screening has its challenges. Although CT imaging is highly sensitive, it is expensive and frequently unavailable in the locations where the disease is managed. Although ultrasound is more widely available, false negative results have been reported in up to 80% of patients.6 Therefore, knowledge of the predictive utility of the clinical findings in patients with prostatic involvement has significant appeal.

In this series, the absence of urinary symptoms and a urinary leukocyte count of < 50 × 106/L both had an NPV for prostatic abscess of over 95%. These findings are similar to the aforementioned Darwin series where 93% of prostatic abscesses had clinical evidence of prostatic infection (defined as the presence of urinary symptoms, an abnormal prostate on examination, an abnormal urinalysis, or a positive urine culture for B. pseudomallei).5

These data suggest that a simple history and basic laboratory investigations can exclude the presence of a prostatic abscess in patients with melioidosis relatively reliably. This might be used to assist clinical decision-making: if a patient lacks urinary symptoms and pyuria, clinicians in well-resourced settings may feel happy to observe patients without prostatic imaging; meanwhile, clinicians in remote or resource-poor settings without access to imaging might have greater confidence that relapse from a prostatic source in these patients is unlikely.

Despite the apparent clinical utility of history and urine microscopy, DRE findings may be less helpful. DRE was rarely documented in our series, highlighting the decline in its use in modern clinical assessment generally;7 however, it was notable that no tenderness was elicited in six of the 11 patients with a prostatic abscess in whom DRE was performed. This echoes the findings of the Darwin series where only half the patients had prostatic tenderness on DRE, and even when tenderness was present it was often surprisingly mild.5 Another similarity with the Darwin series is an association between the presence of prostatic abscess with hazardous alcohol consumption, although the underlying biological mechanism for this association is unclear.

Melioidosis is also endemic in Southeast Asia, and high rates of prostatic involvement have been reported in several Asian series. In a study from a tertiary referral center in Brunei 6/10 (60%) cases of male melioidosis patients had prostatic involvement,8 and although prostatic involvement was not specifically highlighted, urogenital involvement was described in 13% of cases in a Taiwanese series.9 Some Asian series suggest a far lower rate of prostatic abscesses compared with Australian studies;10,11 however, almost all the cases in these series used ultrasound as the imaging modality which is likely to underestimate the true incidence. Singaporean investigators report that prostatic abscesses have been recognized more frequently in patients with melioidosis with increasing use of CT in that country.6 Certainly CT improves radiological assessment of the prostate and is less operator dependent than ultrasound.12,13

Eight patients in our series received a shorter antibiotic course than is presently recommended in international guidelines, although none of the eight had disease recurrence or other adverse outcomes.1 Five of the eight had their abscesses surgically drained, raising the possibility that the duration of antibiotic therapy might be shortened if source control can be achieved.4,14 However, given the high risk of relapse in melioidosis, and the potentially life-threatening repercussions, this would need to be confirmed prospectively.15

Most authors suggest drainage of prostatic abscess > 10–15 mm in diameter, although the preferred drainage method is more controversial.5,6 TRUS-guided needle aspiration or incision, or transurethral drainage are currently the methods of choice. TRUS-guided needle aspiration has the advantage of avoiding the morbidity of transurethral drainage, notably retrograde ejaculation in younger patients; however, repeat procedures are often required.5 In our cohort the median age was 56 years; therefore, TRUS-guided drainage remains a reasonable first option in those wishing to maintain ejaculatory function.

Prostatic abscess is a common manifestation of systemic melioidosis and should be considered and excluded in all male patients. CT imaging is very sensitive–and also identifies other abscesses in the abdomen and pelvis–but it is not always available where cases are managed. Our data suggest that a simple history and basic laboratory investigations can exclude prostatic abscess in patients in areas without access to sophisticated imaging, assisting clinical decision-making, and prioritizing the use of finite health resources.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wiersinga WJ, Currie BJ, Peacock SJ, 2012. Melioidosis. N Engl J Med 367: 1035–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng AC, Currie BJ, 2005. Melioidosis: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev 18: 383–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Currie BJ, Ward L, Cheng AC, 2010. The epidemiology and clinical spectrum of melioidosis: 540 cases from the 20 year Darwin prospective study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 4: e900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart JD, Smith S, Binotto E, McBride WJ, Currie BJ, Hanson J, 2017. The epidemiology and clinical features of melioidosis in far north Queensland: implications for patient management. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11: e0005411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morse LP, Moller CC, Harvey E, Ward L, Cheng AC, Carson PJ, Currie BJ, 2009. Prostatic abscess due to Burkholderia pseudomallei: 81 cases from a 19-year prospective melioidosis study. J Urol 182: 542–547, discussion 547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng TH, How SH, Amran AR, Razali MR, Kuan YC, 2009. Melioidotic prostatic abscess in Pahang. Singapore Med J 50: 385–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kessler C, Bauer SJ, 2012. Utility of the digital rectal examination in the emergency department: a review. J Emerg Med 43: 1196–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chong Vh VH, Sharif F, Bickle I, 2014. Urogenital melioidosis: a review of clinical presentations, characteristic and outcomes. Med J Malaysia 69: 257–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou DW, Chung KM, Chen CH, Cheung BM, 2007. Bacteremic melioidosis in southern Taiwan: clinical characteristics and outcome. J Formos Med Assoc 106: 1013–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Punyagupta S, 1989. Meliodosis. Review of 686 Cases and Presentation of a New Clinical Classification. Bangkok, Thailand: Bangkok Medical Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhiensiri T, Eua-Ananta Y, 1995. Visceral abscess in melioidosis. J Med Assoc Thai 78: 225–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaccaro JA, Belville WD, Kiesling VJ, Jr, Davis R, 1986. Prostatic abscess: computerized tomography scanning as an aid to diagnosis and treatment. J Urol 136: 1318–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinto A, Pinto F, Faggian A, Rubini G, Caranci F, Macarini L, Genovese EA, Brunese L, 2013. Sources of error in emergency ultrasonography. Crit Ultrasound J 5 (Suppl 1): S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sawyer RG, et al. 2015. Trial of short-course antimicrobial therapy for intraabdominal infection. N Engl J Med 372: 1996–2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Limmathurotsakul D, Chaowagul W, Chierakul W, Stepniewska K, Maharjan B, Wuthiekanun V, White NJ, Day NP, Peacock SJ, 2006. Risk factors for recurrent melioidosis in northeast Thailand. Clin Infect Dis 43: 979–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]