Abstract.

Case reports and pathology series suggest associations of female genital schistosomiasis (Schistosoma haematobium) with infertility and ectopic pregnancy. Differential geographic distribution of infertility is not explained by analyses of known risk factors. In this cross-sectional multilevel semi-ecologic study, interpolated prevalence maps for S. haematobium and Schistosoma mansoni in East Africa were created using data from two open-access Neglected Tropical Diseases Databases. Prevalence was extracted to georeferenced survey sample points for Demographic and Health Surveys for Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda for 2000 and 2010. Exploratory spatial analyses showed that infertility was not spatially random and mapped the clustering of infertility and its co-location with schistosomiasis. Multilevel logistic regression analysis demonstrated that women living in high compared with absent S. haematobium locations had significantly higher odds of infertility (2000 odds ratio [OR] = 1.5 [confidence interval95 = 1.3, 1.8]; 2010 OR = 1.2 [1.1, 1.5]). Women in high S. haematobium compared with high S. mansoni locations had significantly higher odds of infertility (2000 OR 1.4 [1.1, 1.9]; 2010 OR 1.4 [1.1, 1.8]). Living in high compared with absent S. mansoni locations did not affect the odds of infertility. Infertility appears to be associated spatially with S. haematobium.

INTRODUCTION

Published reports of the effects of schistosomiasis on reproductive outcomes are limited to case reports and descriptive series suggesting increased risk of prematurity and of low birth weight,1 reports of schistosomiasis prevalence in pregnant women,2 and many case reports of genital schistosomiasis associated with infertility and with ectopic pregnancy.3 Exploration of the spatial distribution of these outcomes of interest in relation to that of the predominant forms of schistosomiasis is one approach to study these effects.

More than 250 million people are affected by schistosomiasis, more than 90% of these in Africa.4 Distribution of human disease is related to that of Schistosoma species–specific host snail populations, with local human prevalence extremely high (50–80%) in areas populated by infected snails.5 Although one host snail species typically predominates in a given geographic region, no specific habitat factors explain the overall difference in species geographic distribution.6 Historically, prevalence surveys have measured egg shedding in urine or feces (measuring presence of reproducing worm pairs) but not disease (organ damage).7

Schistosomiasis affects genitourinary (Schistosoma haematobium) and digestive organs (primarily Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum) and has immunologic and other systemic effects.8 Female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) occurs when deposition of (primarily) S. haematobium eggs leads to granulomas, ulceration, and distortion in ureters, fallopian tubes, and other genitourinary organs, and occurs in 30–75% of women who have urinary schistosomiasis.9 The prevalence of upper reproductive tract FGS is unknown because of difficulty of assessment and lack of clinically apparent manifestations, but pelvic ultrasound abnormalities (ovarian cyst, uterine mass, and hydrosalpinx) were seen in 9% of women in one FGS-affected community in Madagascar (baseline unknown).10 Genital symptoms were already present in 10- to 12-year-old South African girls with urinary schistosomiasis,11 and genital damage may not regress unless treated early.12

Infertility, a common consequence of upper reproductive tract disease, has serious social consequences for women, including divorce, stigma, socioeconomic burden, and presumption of infidelity/sexually transmitted infections (STIs) as the cause.13 Combined analyses of more than 300 Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and reproductive health surveys have produced global prevalence estimates of 2–4% for primary (never having given birth) and 10–40% for secondary (no subsequent births) infertility, with secondary infertility increasing sharply with age (from 2–5% of 20- to 25-year-old women to 60–70% of 40- to 50-year-old women).14 Wide variations in infertility prevalence among countries have been found, with highest risk in sub-Saharan Africa.15 Where medical investigation has occurred, tubal factors account for a much higher proportion of infertility in Africa than in other regions.16 Where bacteriologic testing has been done, 30–70% of tubal disease was due to Chlamydia, 15–50% to gonorrhea, and 6–21% to genitourinary tuberculosis.17 Other possible etiologies of fallopian tube disease may not be considered, as the diagnosis of tubal distortion or obstruction is often made by radiologic imaging only (hysterosalpingogram) without microbiologic or pathologic testing.17

Investigations of ethnicity, sexual patterns, STI risk, and age-cohort effects have not successfully explained the geographic differences in infertility.18 Analyses of African infertility from DHS or World Fertility Surveys have identified associations with urban residence and variation among cultural groups19 and in Ethiopia suggested an unknown ecological factor.20 High prevalence of infertility in proximity to water bodies was noted in Congo, Tanzania, and Kenya.21 Highest regional-level infertility risks in Kenya and Tanzania are in coastal, central plateau, and island (Zanzibar) regions,18,19 which are also S. haematobium–endemic areas.

The same tubal pathology which causes infertility may lead to ectopic pregnancy, a major but poorly documented contributor to maternal mortality in developing countries. Twenty-five percentage of maternal deaths in an urban slum in Nairobi, Kenya, in 2009–2013 were estimated to be due to ectopic pregnancy,22 and hospital series in Ghana and South Africa reported 1–4% of pregnancies as ectopic with 53–61% in hypovolemic shock on arrival.23,24

In addition to many case reports,3 two small community-based studies have addressed the possible association of FGS with infertility. In two S. haematobium–affected communities in Zimbabwe, 15% of women were infertile, with odds ratio (OR) 3.6 for FGS.25 Subfertility was found in 44% of women in a highly schistosomiasis-endemic area of Coast Province, Tanzania.26

The aim of this study was to explore associations of infertility with schistosomiasis using spatial and regression methods, hypothesizing that infertility is associated with residence in S. haematobium–prevalent areas but not in S. mansoni–prevalent areas. This hypothesis suggests an effect of FGS rather than a general immunologic or other systemic effect of schistosomiasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional multilevel semi-ecologic study included Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda as a contiguous geographic region with clearly delineated distribution of the two Schistosoma species of interest and with established DHS programs using the same methodology for collection of outcome data within a 2-year period. We hypothesized that infertility is associated with residence in high compared with low S. haematobium–endemic locations, is associated with residence in high S. haematobium–endemic compared with high S. mansoni–endemic locations, and does not differ with residence in high compared with low S. mansoni–endemic locations.

Data sources.

The primary exposure data source was the Global Neglected Tropical Diseases Database of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (www.gntd.org). For this open-access georeferenced database, schistosomiasis prevalence and location data were abstracted from scientific articles and institutional reports (World Health Organization [WHO], government, control programs) published since the year 1900.27 Most studies determined point prevalence based on egg counts using the Kato-Katz stool method for S. mansoni and urine filtration for S. haematobium. For our study, additional Schistosoma prevalence data were obtained from the Global Atlas of Helminth Infection (thiswormyworld.org), a similar database project of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.28,29 To address areas with sparse data, additional data points were obtained from the WHO 1987 Global Atlas of Schistosomiasis30 and geocoded (using Google Earth) by name of village and approximate map location. To address border issues in interpolation, data for surrounding countries were included with the Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda data, to cover an area from 16° N to −12° S latitude and from 28° W to 8° E longitude.

Prevalence maps for each of the two Schistosoma species were produced using ArcGIS Geostatistical Analyst extension, testing various interpolation methods and models to map the predicted distribution and prediction error. The empirical Bayesian kriging model produced the lowest prediction error (root-mean-square standardized error 0.95 for S. haematobium and 0.97 for S. mansoni) (Figure 1). Several studies have used these databases and methods to produce national and regional schistosomiasis prevalence and risk maps.31–33

Figure 1.

Predicted distribution of Schistosoma haematobium and Schistosoma mansoni in East Africa. Empirical Bayesian kriging interpolation surface, ArcGIS Pro Geostatistical Analyst. Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) sample cluster sites. Data sources: Global Neglected Tropical Diseases Database, Global Atlas of Helminth Infection, World Health Organization Global Atlas of Schistosomiasis, and DHS (Measure DHS). This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Outcomes and covariates were derived from DHS, a program of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) supporting collection and analysis of data about women’s and children’s health, fertility, and social factors, using standard questionnaires and methodologies.34,35 Surveys use a two-stage sampling method with nationally representative selection of DHS clusters (modified for rural/urban and regional stratification) followed by probability proportional to size selection of households. All women of reproductive age (15–49) within each selected household are surveyed. For this analysis, surveys were combined for each of two time periods: Ethiopia 2000, Tanzania 1999, and Uganda 2000 (referred to in this report as “2000 survey”) and Ethiopia 2011, Kenya 2008, Tanzania 2010, and Uganda 2011 (“2010 survey”). Data of the 2000 Kenya survey were not georeferenced.

Interpolated schistosomiasis prevalence was extracted to georeferenced DHS data points following DHS guidance relative to its geomasking displacement process.36 Exposure was categorized as high (> 25%), moderate (5–25%), or low (< 5%) for each of the two Schistosoma species, based on apparent natural breaks in histograms of the spatial data, commonly used programmatic categorizations, and sample size considerations.

Our study population consisted of women aged 15–49 years, married or in union for at least 5 years, not using a contraceptive, and not presently pregnant. Infertility was defined as no live birth within the last 5 years, including both primary (never having given birth) and secondary (having previously given birth) infertility. Established methods to operationalize these definitions for analysis with demographic survey data were followed.37,38

Ethical review.

Review was waived by the Emory University Institutional Review Board. Data use agreements were executed for Measure DHS (USAID), the Global Neglected Tropical Diseases Database, and the Global Atlas of Helminth Infections.

Analysis.

Analyses were carried out using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC), ArcGIS 10.3 (ESRI, Redland, CA), and GeoDa 1.6.6 (Center for Spatial Data Science, Chicago, IL).39 We followed DHS guidance for spatial and regression modeling of associations between DHS variables and environmental exposures.40,41

In addition to development of interpolated spatial models to quantify exposure (schistosomiasis prevalence), spatial methods (assessment of autocorrelation and cluster analysis) were used to assess spatial distribution of infertility.42,43 Spatial analysis addresses the questions of whether the data are autocorrelated (not randomly spatially distributed) and where any clustering/aggregation occurs, and suggests spatial factors associated with this clustering. Spatial distribution of infertility was explored analytically (global and local Moran’s I) and visually (Getis-Ord cluster and hotspot mapping). Possible associations of outcome with exposures were explored visually with map overlay and analytically as Bivariate Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA).

ORs were estimated in a weighted multilevel logistic regression model using SAS PROC GLIMMIX (SAS Institute, Inc.). This mixed model included random-intercept effects for country/survey round (third level) and for DHS cluster (second level), and fixed effects at first (individual) and second level. As DHS second-stage sampling is by household with all eligible women in the household included (mean 1.05 women per household for the study population), inclusion of household as a level was considered, but produced no change in model fit or in estimates.

Indicator variables for the two levels of comparison for each of the two Schistosoma species were measured at the second (DHS cluster) level. Covariates included known risk factors of age (first level) and rural/urban status (second level). Estimates were weighted by DHS sample weights adjusted for differing country-level sampling fractions. For each of the two survey rounds, the model tested five parts of the hypothesis, comparing high and moderate levels of each species to its absence as well as high levels of the two species, and controlling for co-endemicity. ORs were also estimated for important subsets: primary infertility, exposure for more than 10 years, and exposure before age 10. Magnitude and precision of estimates were verified in sensitivity analysis, including various age restrictions (minimum 15–20, maximum 45–50), exposure cutoff points (10%, 30%), and combinations of countries (Supplemental Table 1). Associations were considered significant if the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the OR did not include 1. Population attributable fraction (PAF) was reported, to show the magnitude of significant associations.

RESULTS

Descriptive.

In each survey round, 13% of the married noncontracepting women were presently pregnant. For each survey round, neither marriage duration nor contraceptive use (selection criteria) nor woman’s age was associated with schistosomiasis prevalence (t test, P < 0.5). For each of the two survey sets, 14% of women lived in areas of high S. haematobium prevalence, 48% in moderate, and 38% in low prevalence. Twelve percentage lived in areas of high S. mansoni prevalence, 50% in moderate, and 37% in low prevalence. Table 1 shows that 35% of married noncontracepting women in the 2000 survey round were infertile, with the expected age-related increase from 13% of youngest to 69% of oldest groups. Eighty percentage lived in rural locations; urban women had 3.1 times the odds of infertility. Of 17,547 women in the 2010 survey round, 35% were infertile, increasing from 11% of the youngest to 72% of the oldest. Eighty-one percentage lived in rural locations; urban women had 2.5 times the odds of infertility.

Table 1.

Study population description

| 2000 Survey round | 2010 Survey round | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethiopia | Tanzania | Uganda | Total | Ethiopia | Kenya | Tanzania | Uganda | Total | |

| Number of women | 8,357 | 1,747 | 2,840 | 12,944 | 7,314 | 2,758 | 3,945 | 3,530 | 17,547 |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Age 15–19 | 168 (2) | 6 (< 1) | 2 (1) | 200 (2) | 92 (1) | 13 (1) | 9 (< 1) | 24 (< 1) | 138 (1) |

| 20–29 | 2,736 (33) | 610 (35) | 1,295 (46) | 4,647 (36) | 2,497 (34) | 867 (31) | 1,125 (29) | 1,288 (36) | 5,757 (33) |

| 30–39 | 3,087 (37) | 685 (39) | 1,050 (37) | 4,822 (37) | 2,730 (37) | 1,045 (38) | 1,556 (39) | 1,292 (37) | 6,634 (38) |

| 40–49 | 2,366 (28) | 457 (26) | 652 (23) | 3,475 (27) | 1,995 (27) | 833 (30) | 1,255 (32) | 926 (26) | 5,009 (29) |

| Rural | 6,930 (82) | 1,293 (73) | 2,543 (78) | 10,766 (80) | 6,024 (82) | 2,146 (78) | 3,319 (82) | 2,848 (80) | 14,237 (81) |

| Ever lost pregnancy | 1,562 (19) | 506 (29) | 762 (27) | 2,830 (22) | 974 (13) | 457 (17) | 1,032 (26) | 997 (28) | 3,460 (20) |

| Infertility | 2,828 (34) | 684 (39) | 875 (31) | 4,534 (35) | 2,600 (36) | 1,107 (40) | 1,461 (37) | 1,015 (28) | 6,183 (35) |

| Total | 2,828 (34) | 644 (37) | 840 (30) | 4,312 (33) | 2,451 (34) | 985 (36) | 1,371 (35) | 971 (27) | 5,831 (33) |

| Age 15–29 | 428 (15) | 92 (15) | 105 (8) | 625 (13) | 368 (14) | 83 (9) | 113 (10) | 86 (7) | 650 (11) |

| Age 30–39 | 801 (26) | 228 (33) | 277 (26) | 1,306 (27) | 703 (26) | 319 (30) | 412 (26) | 255 (20) | 1,689 (25) |

| Age 40–49 | 1,599 (68) | 324 (71) | 458 (70) | 2,381 (69) | 1,380 (69) | 636 (76) | 846 (67) | 630 (68) | 3,492 (72) |

| Primary | 392 (4) | 66 (4) | 93 (3) | 551 (4) | 285 (4) | 50 (2) | 124 (3) | 54 (2) | 513 (3) |

Women aged 15–49 years, married or in union for at least 5 years, not using a contraceptive. Source: Demographic and Health Surveys Ethiopia 2000, Tanzania 1999, and Uganda 2001 (2000 survey round); Ethiopia 2011, Kenya 2009, Tanzania 2009, and Uganda 2011 (2010 survey round). Infertile = no birth within last 5 years. Primary = never given birth.

Spatial analysis of outcomes.

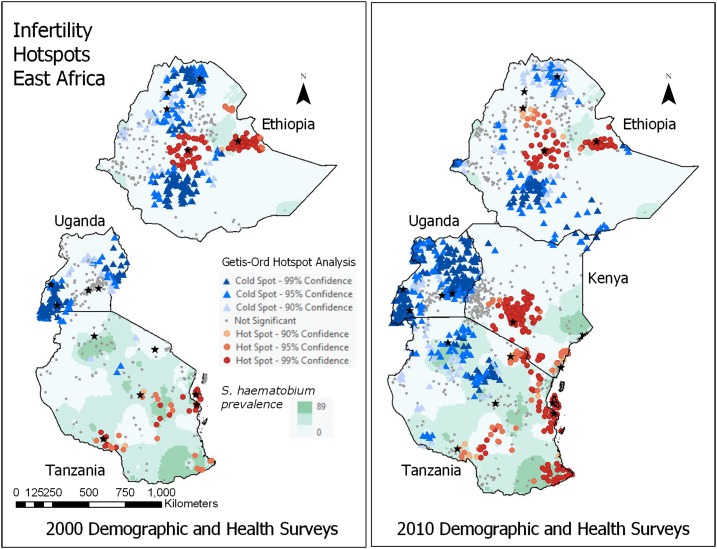

The distribution of infertility was not spatially random (was autocorrelated) for both survey rounds (2000 Moran’s I = 0.53 and 2010 Moran’s I = 1.00), suggesting moderate to strong clustering. As shown in Figure 2 (Getis-Ord analysis), in both survey rounds, infertility hotspots were seen in central and eastern Ethiopia; and in coastal, central plateau, southwest lake, southeast lake/coast, and island (Zanzibar) Tanzania. In the 2010 survey, hotspots were also noted in central and coastal Kenya. Many hotspots appeared to overlie major urban centers (central Ethiopia and Kenya, coastal Tanzania) or areas of high S. haematobium prevalence (dark background on map).

Figure 2.

Getis-Ord hotspot analysis, infertility in East Africa; overlying *major cities (known risk factor) and Schistosoma haematobium prevalence (hypothesized risk factor). ArcGIS Pro (ESRI). Data sources: Demographic and Heath Surveys (Measure DHS), Global Neglected Tropical Diseases Database, Global Atlas of Helminth Infection, and World Health Organization Global Atlas of Schistosomiasis. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

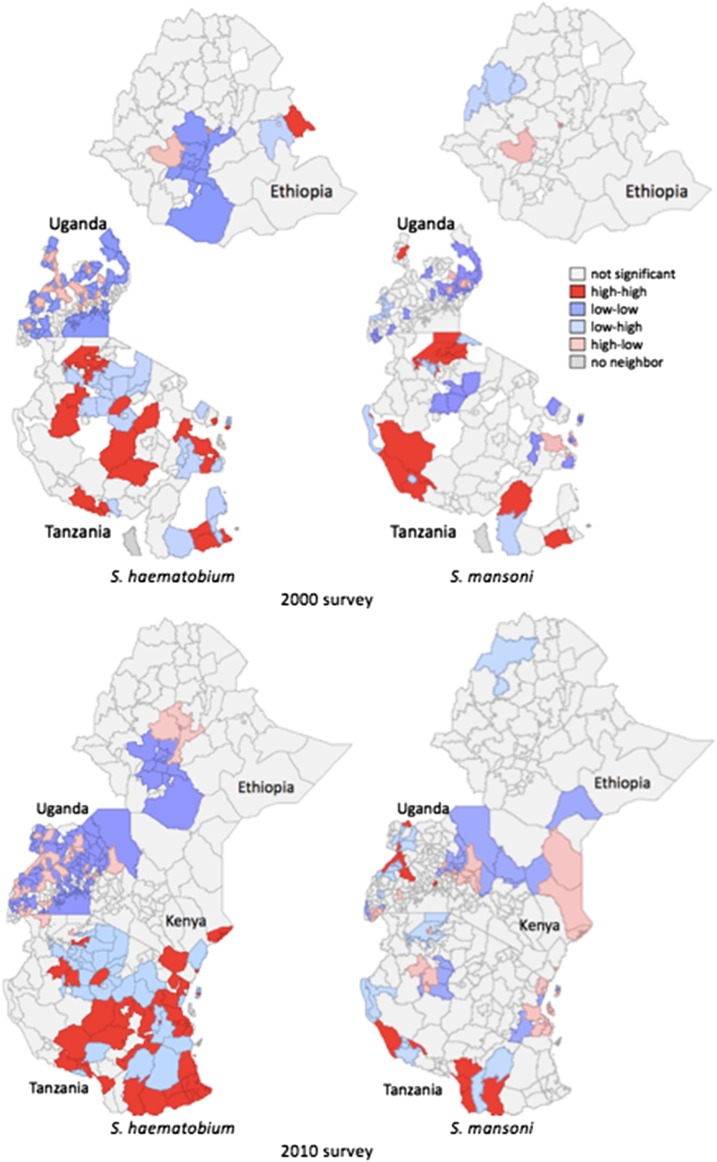

In Figure 3, Bivariate LISA maps show that high infertility and high S. haematobium prevalence are in similar locations in several parts of Tanzania and in coastal Kenya, and S. mansoni in a few locations in Tanzania and western Uganda. The large mapped areas of high-high (red) and low-low (dark blue) co-location of infertility with S. haematobium suggest an association, with fewer such areas seen in the S. mansoni maps.

Figure 3.

Association of infertility with schistosomiasis, East Africa. Bivariate Local Indicators of Spatial Association, as maps of local-scale associations. GeoDa 1.6.6. Data sources: Demographic and Heath Surveys (Measure DHS), Global Neglected Tropical Diseases Database, Global Atlas of Helminth Infection, and World Health Organization Global Atlas of Schistosomiasis. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Regression analysis.

For the 2000 survey round, intraclass correlation coefficients indicated that 7% of variability in infertility was between DHS geographic clusters, 1% between countries, and 92% between individuals. For 2010 surveys, 11% of variability in infertility existed between DHS clusters, 0.3% between countries, and 89% between individuals.

As shown in Table 2, women living in high compared with absent S. haematobium locations had significantly higher odds of infertility in both the 2000 (OR 1.53) and 2010 (OR 1.24) surveys. Women living in moderate compared with absent S. haematobium locations had significantly higher odds of infertility in the 2010 survey (OR 1.31). Women living in high S. haematobium compared with high S. mansoni locations had significantly higher odds of infertility for both the 2000 (OR 1.41) and the 2010 (OR 1.44) surveys. Living in high or moderate S. mansoni locations was not associated with infertility. By PAF, 7% [CI95 4.3, 9.4] (2000 survey) and 4% [CI95 1.2, 7.2] (2010 survey) of infertility cases were associated with residence in high S. haematobium areas and 11% (2010 survey) with residence in moderate S. haematobium areas.

Table 2.

Association of infertility with schistosomiasis prevalence at residence

| 2000 Survey | 2010 Survey | |

|---|---|---|

| Total infertility | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| S. h high (ref = absent) | 1.53 (1.27, 1.85)* | 1.24 (1.06, 1.47)* |

| S. h moderate | 1.14 (0.99, 1.32) | 1.31 (1.15, 1.49)* |

| S. m high | 1.09 (0.89, 1.33) | 0.86 (0.73, 1.02) |

| S. m moderate | 1.01 (0.87, 1.17) | 1.02 (0.90, 1.16) |

| S. h high (ref = S. m high) | 1.43 (1.08, 1.90)* | 1.44 (1.14, 1.81)* |

| Primary infertility | ||

| S. h high (ref = absent) | 1.78 (1.61, 2.37)* | 1.53 (1.05, 2.25)* |

| S. h moderate | 1.47 (1.08, 2.00)* | 1.34 (0.99, 1.81) |

| S. m high | 1.12 (0.73, 1.73) | 0.54 (0.35, 0.84)* |

| S. m moderate | 1.25 (0.92, 1.70) | 1.31 (0.98, 1.75) |

| S. h high (ref = S. m high) | 1.44 (0.82, 2.53) | 2.83 (1.60, 5.00)* |

= significant; CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; ref = reference; S. h = Schistosoma haematobium; S. m = Schistosoma mansoni; high = > 25%; moderate = 5–25%; absent = < 5%. Women aged 15–49 years, married or in union for at least 5 years, not using a contraceptive. Source: Demographic and Health Surveys, Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Uganda (2000 survey round); Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Uganda (2010 survey round).

To address possible temporal effects, three subgroups were analyzed. The sample of women with primary infertility was small, 551 (2000 survey) and 513 (2010 survey). Table 2 shows that women living in high compared with absent S. haematobium locations had significantly higher odds of primary infertility in both the 2000 (OR 1.78) and 2010 (OR 1.53) surveys. Women living in moderate compared with absent S. haematobium locations had significantly higher odds of primary infertility in the 2000 survey (OR 1.47). Women living in high S. haematobium compared with high S. mansoni locations had significantly higher odds of primary infertility for the 2010 survey (OR 2.83).

As duration of residence at current location was measured in the 2000 survey round, some assessment of temporal factors was possible. Table 3 shows that women living in high compared with absent S. haematobium locations for at least 10 years had significantly higher odds of infertility (OR 1.47). Women living in high compared with absent S. haematobium locations since before age 10 had significantly higher odds of infertility (OR 1.69). Women living since before age 10 in high S. haematobium compared with high S. mansoni locations also had significantly higher odds of infertility (OR 1.66).

Table 3.

Association of impaired fertility with schistosomiasis prevalence of residence and duration of exposure

| Resident > 10 years | Resident before age 10 | |

|---|---|---|

| Infertility | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| S. h high (ref = absent) | *1.47 (1.19, 1.81) | *1.69 (1.31, 2.17) |

| S. h moderate | 1.13 (0.96, 1.33) | 1.18 (0.96, 1.44) |

| S. h high (ref = S. m high) | 1.35 (1.00, 1.83) | *1.66 (1.15, 2.40) |

= significant; CI = confidence interval; S. h = Schistosoma haematobium; high = > 25%; moderate = 5–25%; absent = < 5%. OR = odds ratio. Women aged 15–49 years, married or in union for at least 5 years, not using a contraceptive. Source: Demographic and Health Surveys Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda (2000 survey round).

Sensitivity analysis of various country groupings, exposure prevalence cut points, and age cutoffs consistently found infertility to be associated with residence in high compared with absent S. haematobium locations and in high S. haematobium compared with high S. mansoni locations (Supplemental Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Infertility was significantly associated with residence in areas of high S. haematobium prevalence, compared with both S. haematobium absence and to equivalent S. mansoni prevalence. Infertility was not associated with S. mansoni prevalence. This suggests that the association is related not to unmeasured confounders of the presence/absence of schistosomiasis but to the differing clinical manifestations of the two Schistosoma species (i.e., the tubal or other urogenital damage of S. haematobium rather than the hepatic damage of S. mansoni). Schistosoma mansoni occasionally causes FGS; residence in co-endemic areas was addressed in the model. There does not appear to be a proportional effect of the exposure, as ORs did not differ proportionally for high and for moderate S. haematobium prevalence. The usual prevalence measure (proportion of sampled schoolchildren excreting eggs on a given day), although useful as a measure of transmission, does not accurately measure the prevalence of disease, which is cumulative and persistent.7

Associations, although statistically significant by OR CIs, were not of large magnitude. PAF illustrates the magnitude of effect, with 7% of 2000 infertility cases and 15% of 2010 cases associated with S. haematobium exposure.

An inherent limitation of cross-sectional study design is the difficulty assessing temporal factors. Infertility may result from exposures occurring up to 50 years previously.11 Genital schistosomiasis lesions occur within a few years of exposure and may persist despite antihelminthic treatment.12 Thus, the disease (infertility due to tubal damage) may reflect either remote childhood exposure or more recent migration into an endemic area. Assuming a 5-year lag time between exposure to the parasite and occurrence of tubal disease and an additional lag time of the 5 years’ exposure to pregnancy necessary to define infertility, women known to have resided locally for at least 10 years were analyzed. Associations were of similar magnitude to those for the total population. To assess the effect of childhood exposure, women known to have lived in the exposure area since before age 10 were analyzed, also showing associations of similar magnitude to the total population. These two subgroup analyses were only available for the 2000 surveys.

Primary infertility includes women for whom the etiology of infertility was either innate or of onset earlier in life, possibly including those with childhood FGS. Infections acquired after sexual debut (STIs, pregnancy-related infections) contribute more to secondary infertility.17 For primary infertility, the associations with S. haematobium exposure were at least as strong as for total infertility, with higher upper confidence limits.

Temporal factors also may affect the exposure measurement, as schistosomiasis prevalence data were collected over a century. However, maps from various times show no apparent change in the prevalence in the study area.30,33 None of the countries in this study had implemented nationwide high-coverage schistosomiasis control programs far enough before the relevant DHS surveys to have affected the outcomes measured in this study.44

Exposure was measured not individually but ecologically, based on current residence. Individual exposure to schistosomiasis within an endemic area varies with lifetime water exposure behaviors as well as with focal distribution of infected snails. Schistosomiasis distribution is heterogeneous at local and seasonal scale. Although this local heterogeneity may affect the precision of kriging-generated estimates, the Bayesian methods used best address this uncertainty.31 In this study, the prediction error was very low, and mapping demonstrated low standard error except in sparsely populated regions as indicated by few DHS data points (Supplemental Figure 1).

An ideal measure of impaired fertility would include miscarriages, stillbirths, and ectopic pregnancies as well as live births.45,46 Pregnancy losses (stillbirths and miscarriages) were not measureable in all surveys and are known to be biased because of under-reporting in DHS surveys.47 Survival bias may be a factor if ectopic pregnancy is associated with S. haematobium exposure. As DHS surveys only living women, any women who have died of ruptured ectopic pregnancy would not be counted as either cases or subjects, potentially biasing study results toward the null (i.e., true associations may be stronger). A reliable method of measuring the incidence of ectopic pregnancy, a commonly fatal manifestation of tubal infertility, is needed. Infertility risk can be considered only suggestive of the risk of this major cause of maternal mortality.

This study addressed infertility as a female outcome. Although S. haematobium may damage male as well as female reproductive organs,48 the role of infertility and exposure status of the male partner was not addressed.

The association with schistosomiasis increases the evidence that impaired fertility may have etiologies other than STIs and should not be equated with stigmatized sexual behaviors. Schistosomiasis contributes to the women’s disease burden of infertility, with its social consequences of stigma and family disruption. If infertility can be considered a surrogate measure of ectopic pregnancy, schistosomiasis may also contribute to the burden of maternal mortality in Africa. Women presenting with infertility or ectopic pregnancy should be evaluated and treated for schistosomiasis if geographically appropriate, although this may not reverse established tubal damage. Prevention efforts should ensure inclusion of girls and women in schistosomiasis control programs.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figures and Table

Note: Supplemental figures and table appear at www.ajtmh.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Friedman JF, Mital P, Kanzaria HK, Olds GR, Kurtis JD, 2007. Schistosomiasis and pregnancy. Trends Parasitol 23: 159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salawu OT, Odaibo AB, 2014. Maternal schistosomiasis: a growing concern in sub-Saharan Africa. Pathog Glob Health 108: 263–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christinet V, Lazdins-Helds JK, Stothard JR, Reinhard-Rupp J, 2016. Female genital schistosomiasis (FGS): from case reports to a call for concerted action against this neglected gynaecological disease. Int J Parasitol 46: 395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hotez PJ, Fenwick A, 2009. Schistosomiasis in Africa: an emerging tragedy in our new global health decade. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 3: e485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colley DG, Bustinduy AL, Secor WE, King CH, 2014. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet 383: 2253–2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdel-Malek E, 1958. Factors conditioning the habitat of bilharziasis intermediate hosts of the family Planorbidae. Bull World Health Organ 18: 785–818. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Werf MJ, de Vlas SJ, Brooker S, Looman CW, Nagelkerke NJ, Habbema JD, Engels D, 2003. Quantification of clinical morbidity associated with schistosome infection in sub-Saharan Africa. Acta Trop 86: 125–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King CH, Dangerfield-Cha M, 2008. The unacknowledged impact of chronic schistosomiasis. Chronic Illn 4: 65–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poggensee G, Feldmeier H, 2001. Female genital schistosomiasis: facts and hypotheses. Acta Trop 79: 193–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leutscher P, Raharisolo C, Pecarrere JL, Ravaoalimalala VE, Serieye J, Rasendramino M, Vennervald B, Feldmeier H, Esterre P, 1997. Schistosoma haematobium induced lesions in the female genital tract in a village in Madagascar. Acta Trop 66: 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hegertun IE, Sulheim Gundersen KM, Kleppa E, Zulu SG, Gundersen SG, Taylor M, Kvalsvig JD, Kjetland EF, 2013. S. haematobium as a common cause of genital morbidity in girls: a cross-sectional study of children in South Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7: e2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kjetland EF, Mduluza T, Ndhlovu PD, Gomo E, Gwanzura L, Midzi N, Mason PR, Friis H, Gundersen SG, 2006. Genital schistosomiasis in women: a clinical 12-month in vivo study following treatment with praziquantel. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 100: 740–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cui W, 2010. Mother or nothing: the agony of infertility. Bull World Health Organ 88: 881–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rutstein SO, Shah IH, 2004. Infecundity, Infertility, and Childlessness in Developing Countries DHS Comparative Reports 9. Available at: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/infertility/DHS-CR9.pdf.

- 15.Mascarenhas MN, Flaxman SR, Boerma T, Vanderpoel S, Stevens GA, 2012. National, regional, and global trends in infertility prevalence since 1990: a systematic analysis of 277 health surveys. PLoS Med 9: e1001356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cates W, Farley TM, Rowe PJ, 1985. Worldwide patterns of infertility: is Africa different? Lancet 2: 596–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayaud P, 2001. The role of reproductive tract infections. Boerma J, Mgalla Z, eds. Women and Infertility in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Multidisciplinary Perspective. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Royal Tropical Institute, 71–107. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larsen U, 2000. Primary and secondary infertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Epidemiol 29: 285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ericksen K, Brunette T, 1996. Patterns and predictors of infertility among African women: a cross-national survey of twenty-seven nations. Soc Sci Med 42: 209–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tesfaghiorghis H, 1991. Infecundity and subfertility among the rural population of Ethiopia. J Biosoc Sci 23: 461–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romaniuk A, 1968. Infertility in tropical Africa. Caldwell JC, Okonjo C, eds. The Population of Tropical Africa. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 214–224. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olack B, Cosmas L, Mogeni D, Montgomery J, 2014. Causes of mortality in women of reproductive age living in an urban slum (Kibera) in Nairobi American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Annual Meeting. Abstract #1869. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amoko DH, Buga GA, 1995. Clinical presentation of ectopic pregnancy in Transkei, South Africa. East Afr Med J 72: 770–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindow SW, Moore PJ, 1988. Ectopic pregnancy: analysis of 100 cases. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 27: 371–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kjetland EF, Kurewa EN, Mduluza T, Midzi N, Gomo E, Friis H, Gundersen SG, Ndhlovu PD, 2010. The first community-based report on the effect of genital Schistosoma haematobium infection on female fertility. Fertil Steril 94: 1551–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller-Fellows SC, Howard L, Kramer R, Hildebrand V, Furin J, Mutuku FM, Mukoko D, Ivy JA, King CH. Cross-sectional interview study of fertility, pregnancy, and urogenital schistosomiasis in coastal Kenya: documented treatment in childhood is associated with reduced odds of subfertility among adult women. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11: e0006101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurlimann E, et al. 2011. Toward an open-access global database for mapping, control, and surveillance of neglected tropical diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 5: e1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brooker S, Hotez PJ, Bundy DAP, 2010. The global atlas of helminth infection: mapping the way forward in neglected tropical disease control. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 4: e779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flueckiger RM, et al. 2015. Integrating data and resources on neglected tropical diseases for better planning: the NTD mapping tool ( NTDmap.org). PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9: e0003400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doumenge J, Mott K, Cheung C, Villenave D, Chapuis O, eds., 1987. Atlas of the Global Distribution of Schistosomiasis. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available at: http://www.who.int/schistosomiasis/epidemiology/Global_atlas_toc.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brooker S, 2007. Spatial epidemiology of human schistosomiasis in Africa: risk models, transmission dynamics and control. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 101: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simoonga C, Utzinger J, Brooker S, Vounatsou P, Appleton CC, Stensgaard AS, Olsen A, Kristensen TK, 2009. Remote sensing, geographical information system and spatial analysis for schistosomiasis epidemiology and ecology in Africa. Parasitology 136: 1683–1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schur N, Hürlimann E, Stensgaard AS, Chimfwembe K, Mushinge G, Simoonga C, Kabatereine NB, Kristensen TK, Utzinger J, Vounatsou P, 2013. Spatially explicit Schistosoma infection risk in eastern Africa using Bayesian geostatistical modelling. Acta Trop 128: 365–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Measure DHS , ed., 2012. Survey Organization Manual for Demographic and Health Surveys Calverton, MD: ICF International. Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/DHSM10/DHS6_Survey_Org_Manual_7Dec2012_DHSM10.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Measure DHS , ed., 2012. Demographic and Health Survey Sampling and Household Listing Manual Calverton, MD: ICF International. Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/DHSM4/DHS6_Sampling_Manual_Sept2012_DHSM4.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perez-Heydrich C, Warren J, Burgert C, Emch M, eds., 2013. Guidelines on the Use of DHS GPS Data. Spatial Analysis Reports No. 8 Calverton, MD: ICF International. Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SAR8/SAR8.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larsen U, Menken J, 1991. Individual-level sterility: a new method of estimation with application to sub-Saharan Africa. Demography 28: 229–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mascarenhas MN, Cheung H, Mathers CD, Stevens GA, 2012. Measuring infertility in populations: constructing a standard definition for use with demographic and reproductive health surveys. Popul Health Metr 10: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anselin L, Syabri I, Kho Y, 2006. GeoDa: an introduction to spatial data analysis. Geogr Anal 38: 5. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burgert CR, Bradley SEK, Arnold F, Eckert E, 2014. Improving estimates of insecticide-treated mosquito net coverage from household surveys: using geographic coordinates to account for endemicity. Malar J 13: 254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Curtis S, Hossain M, eds., 1998. West Africa Spatial Analysis Prototype Exploratory Analysis: The Effect of Aridity on Child Nutritional Status DHS Spatial Analysis Reports No. 2. Calverton, MD: Macro International. Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SAR2/GIS2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burgert C, ed., 2014. Spatial Interpolation with Demographic and Health Survey Data: Key Considerations. DHS Spatial Analysis Reports No. 9. Rockville, MD: ICF International. Available at: http://www.gbv.de/dms/zbw/821367854.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gething P, Tatem A, Bird T, Burgert-Brucker C, eds., 2015. Creating Spatial Interpolation Surfaces with DHS Data. DHS Spatial Analysis Reports No. 11. Rockville, MD: ICF International. Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SAR11/SAR11.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tchuem Tchuente L, Rollinson D, Stothard JR, Molyneux D, 2017. Moving from control to elimination of schistosomiasis in sub-Saharan Africa: time to change and adapt strategies. Infect Dis Poverty 6: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gurunath S, Pandian Z, Anderson RA, Bhattacharya S, 2011. Defining infertility—a systematic review of prevalence studies. Hum Reprod Update 17: 575–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Menken J, Larsen U, 1994. Estimating the incidence and prevalence and analyzing the correlates of infertility and sterility. Ann N Y Acad Sci 709: 249–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haws RA, Mashasi I, Mrisho M, Schellenberg JA, Darmstadt GL, Winch PJ, 2010. “These are not good things for other people to know”: how rural Tanzanian women’s experiences of pregnancy loss and early neonatal death may impact survey data quality. Soc Sci Med 71: 1764–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feldmeier H, Leutscher P, Poggensee G, Harms G, 1999. Male genital schistosomiasis and haemospermia. Trop Med Int Health 4: 791–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figures and Table