Abstract

Photothermal therapy (PTT) can be an effective antitumor therapy, but it may not completely eliminate tumor cells, leading to the risk of recurrence or metastasis. Here we describe nanocarriers that allow combination therapy involving PTT and immunotherapy. Nanocarriers are prepared by coating Al2O3 nanoparticles with non-toxic, biodegradable polydopamine, which shows high photothermal efficiency. A near-infrared laser irradiation can kill the majority of tumor tissues, resulting in the release of tumor-associated antigens. The Al2O3 within the nanoparticles, together with CpG, acts as an adjuvant to trigger robust cell-mediated immune responses that can help eliminate the residual tumor cells and reduce the risk of tumor recurrence.

Methods: The characteristics and photothermal performance of polydopamine-coated Al2O3 nanoparticles were examined after one-step preparation. Then we studied their internalization, photothermal toxicity and immunostimulatory activity in vitro. For in vivo experiments, these nanocarriers were injected directly into B16F10 melanoma allografts in mice to ensure specific localization. After photothermal irradiation on day 0, mice were subcutaneously injected with CpG adjuvant on day 1, 3 and 5. Tumor volumes and number of living mice were recorded every two days. Moreover, various immune responses induced by our combined therapy were tested for mechanism research.

Results: 50% of mice after our combined treatment successfully achieved the goal of tumor eradication, and survived for 120 days, which was the end point of the experiment. Mechanism studies demonstrated the combined therapy efficiently led to dendritic cell maturation, resulting in the secretion of antibodies and cytokines as well as the proliferation of splenocytes and lymphocytes for anti-tumor immunotherapy.

Conclusion: Taken together, these results demonstrated the promise of our combined photothermal therapy and immunotherapy for tumor shrinkage, which merited further research.

Keywords: photothermal therapy, immunotherapy, Al2O3 nanoparticles, polydopamine, melanoma.

Introduction

Cancer continues to be a leading cause of morbidity and mortality around the world 1, 2. Standard anticancer therapies, including surgical excision, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, can kill normal cells and destroy the systemic immune system, severely impacting quality of life after several treatments 3. Photothermal therapy (PTT) has recently emerged as an alternative with the potential for high selectivity and extremely low invasiveness 4. In PTT, biomaterials that efficiently convert light energy (usually at near-infrared wavelengths) into heat are inserted into the tumor and illuminated to induce local, lethal heating of the tumor 5. PTT is analogous to photodynamic therapy 6, but without the need for reactive oxygen species to interact with target cells or tissues. Because PTT is based on long-wavelength light, it irradiates the tissue with less energy, minimizing harm to non-target tissues 7.

Many PTT materials have been developed with high photothermal conversion efficiency and strong therapeutic effects in vitro and in small animal studies 8-15. Most of these materials, however, are not widely used in the clinic because of concerns about their long-term safety 16. In contrast to these agents, natural melanin functions well in PTT and shows excellent biocompatibility, reflecting its presence in human hair, skin, liver, and spleen 17, 18. Recently, the primary component of melanin, polydopamine, has shown promise in vitro and in vivo for PTT 19, 20. Polydopamine has several characteristics that make it well-suited to PTT. First, it forms via simple oxidation and self-polymerization of dopamine at room temperature under alkaline conditions 21. Second, it shows good biocompatibility and biodegradation, which should make it safe for long-term administration 22. Third, it adheres easily to other substances. Fourth, it shows good photothermal conversion efficiency in the near-infrared region. Therefore, we focused in the present study on preparing a novel type of polydopamine-based nanoparticle for antitumor PTT.

In our study, we started with an inner core of Al2O3 nanoparticles, which were coated with polydopamine via simple dopamine oxidation and self-polymerization 23, 24, named pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles. In contrast to commonly used Au or Fe3O4 25 nanoparticles, Al2O3 nanoparticles as the inner core of polydopamine have never been reported, and may be a promising adjuvant for the development of therapeutic cancer vaccines 26, since microparticle precipitates of aluminum compounds (known as alum) have been used as immune adjuvants in human vaccines for over 80 years 27.

The incidence of tumor recurrence or metastasis after single tumor-targeting therapies remains high. Combining PTT and immunotherapy can significantly inhibit tumor metastasis 28. This previous work involved systemic delivery of PTT agents, but intravenous injection of tumor-targeting nano-agents could result in quite low accumulation in tumors 29. Therefore, we decided to investigate the feasibility and potency of intratumor administration without systemic toxicity, combined with immunotherapy.

In general, our strategy was to inject the resulting pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles directly into tumors in mice, then irradiate the animals in PTT. The resulting large-scale tumor cell death should release tumor-specific antigens that can trigger a systemic immune response to eliminate residual tumor cells 30. The immunogenicity of these antigens should increase via association with Al2O3 in the nanoparticles. To further increase immunogenicity after PTT, we injected the mice subcutaneously with the widely used, inexpensive adjuvant CpG, which potently stimulates Th1-type cells 31, 32 and has been used in a hepatitis B vaccine 33, 34, recently approved for clinical use by the US Food and Drug Administration. Those beneficial characteristics of CpG may facilitate the optimization and implementation of our approach in the clinic. Thus, the joint action of Al2O3 and CpG was intended to eliminate residual tumor cells and thereby reduce risk of recurrence or metastasis.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Aluminum oxide (Al2O3) nanoparticles were purchased from NanoAmor (Nanostructured & Amorphous Materials, Inc., USA). Dopamine hydrochloride and Fe3O4 nanoparticles were purchased from Aladdin. Propidium iodide (PI), fluorescein diacetate (FDA) and 3-(4,5-dimethyl-thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from Sigma. Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) was purchased from Dojindo Laboratories. Antibodies against cell surface markers for flow cytometry assay and Ready-SET-go! ELISA kits for mouse TNF-α, IFN-γ or IL-4 were purchased from eBioscience.

Preparation of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles

To prepare polydopamine (pD)-Al2O3 nanoparticles with a polydopamine shell approximately 1.5 nm thick, 10 mg of dopamine hydrochloride was suspended in 10 mL of a 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer solution (pH 8.5) containing 1.0 mg/mL Al2O3 nanoparticles. After vigorous stirring at room temperature for 1 h, pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles were easily obtained by centrifugation at 10,000 ×g for 20 min and washed three times with deionized water until a clear solution was obtained. Then pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles were stored in the refrigerator at 4 ℃ for immediate use, or dried in a vacuum freeze dryer for long-term storage. Pure polydopamine was subjected to the same procedure as above, but without addition of Al2O3 nanoparticles, in order to prepare reference samples for Fourier transform IR (FTIR) analysis. In addition, pD-Fe3O4 nanoparticles were prepared as described above, except that the Tris-HCl contained 1.0 mg/mL Fe3O4 nanoparticles. These particles served as a comparison sample for in vivo studies.

Nanoparticle characterization

Hydrodynamic diameters of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles were determined using a Zetasizer Nano-ZS. The morphology and structure of the obtained nanoparticles were characterized by transmission electron microscopy. FTIR and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) mapping were used to investigate the interactions between Al2O3 nanoparticles and polydopamine.

Measurement of photothermal performance

pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles were suspended in deionized water at various concentrations (1,000, 500, 250, 125, 63, 31 and 16 μg/mL), and their absorption spectra in the UV, visible, and near-infrared range were recorded using a UV-vis spectrophotometer.

pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles were dispersed in a quartz cuvette at various concentrations (50-1,000 μg/mL) and irradiated for 600 s using a near-infrared laser at 808 nm (Haoliangtech, Shanghai, China) at a power density of 1.18 W/cm2. Pure water was used as a negative control. The temperature of solutions was measured every 100 s using a digital thermometer with a thermocouple probe. pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles at 1,000 μg/mL were irradiated at 1.18 W/cm2 for 5 min, and their temperature was monitored using an infrared thermal camera (Fotric 225).

Cytotoxicity and photothermal toxicity in vitro

B16F10 cells were seeded into 35 mm confocal dishes, and then incubated for 24 h at 37 ℃ in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Cells were incubated for 1 h with pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles (1.0 mg/mL), irradiated for 5 min with a near-infrared laser (808 nm, 1.18 W/cm2), co-stained with propidium iodide (PI) and fluorescein diacetate (FDA), and then imaged using confocal laser scanning microscopy.

B16F10 cells were incubated for 24 h in 96-well plates at 37 ℃ under 5% CO2, incubated for 1 h with pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles at various concentrations (0-1,000 μg/mL), irradiated or not for 5 min with a near-infrared laser (808 nm, 1.18 W/cm2), and incubated for another 24 h. Cell viability was measured using a standard MTT assay.

Uptake by cells in vitro

B16F10 cells were seeded in 12-well plates at 1.0 x 106 cells/well, incubated for 24 h, then exposed for 1 h to lumogallion-stained pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles (1.0 mg/mL) in the absence of serum or antibiotics. Cells were collected and analyzed by flow cytometry.

In vitro dendritic cell maturation

Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were isolated from C57BL/6 mice, seeded into 12-well plates, and incubated for 24 h with pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles (1.0 mg/mL). Cells were treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) as a positive control or with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as a negative control. Cells were stained with FITC-conjugated antibody against CD80 and PE-conjugated antibody against CD40, then analyzed using flow cytometry. Culture supernatants were assayed for interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Combination of PTT and CpG adjuvant in vivo

To establish melanoma cancer models, B16F10 cells (5.0 x 105 cells/well) suspended in PBS were inoculated into the right side of the back of C57BL/6 mice, close to the armpit. Eight days later, when tumor volumes were close to 100 mm3, pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles (1.0 mg/mL, 100 μL per mouse) were injected directly into B16F10 tumors, then irradiated for 5 min with a laser at 808 nm and 1.18 W/cm2. This time point was defined as day 0. On days 1, 3 and 5, three doses of CpG (3 μg per mouse per injection) were subcutaneously injected into the right forelimb of mice 35. Tumor volume, mouse weight and number of mice alive were recorded every two days. After PTT treatments, tumor temperature was monitored at 0, 1, 3 and 5 min using an infrared thermal camera (Fotric 225). All animal procedures in our experiments were approved by the Experimental Animal Center of Sichuan University.

Dendritic cell maturation in vivo

Mice treated with the combination method of PTT and CpG adjuvant were sacrificed on day 6, and their axillary lymph nodes were collected and co-stained with FITC-conjugated antibody against CD11c (to mark dendritic cells), PE-conjugated antibody against CD40 and PE/Cy5-conjugated antibody against CD86. Cells were then analyzed using flow cytometry to quantitate dendritic cell maturation in tumor-draining lymph nodes (TDLNs) 36, which refer to the axillary lymph nodes on right side of mice.

Cytokine assay

Serum from mice treated with the combination method of PTT and CpG adjuvant was sampled at 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, and 1 week. Serum samples were diluted 2-fold and assayed for TNF-α and IFN-γ using commercial ELISA kits.

Antibody assay

B16F10 cells were lysed, and the lysate was coated onto Costar 9018 enzyme plates. Then wells were loaded with serum sampled at weeks 1 and 2 from mice treated with the combination method of PTT and CpG adjuvant. Then horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-IgG, anti-IgG1 and anti-IgG2a antibodies were added to the wells. Absorbance of wells at 450 nm was measured using a Varioskan Flash reader.

Splenocyte and lymphocyte proliferation

TDLNs and spleens of mice treated with the combination method of PTT and CpG adjuvant were isolated at week 1, ground-up, and passed through a cell strainer to form single-cell suspensions. These suspensions were seeded into 96-well plates (100 μL/well), stimulated with B16F10 cell lysate or not, and incubated for 48 h at 37 ℃ under 5% CO2. CCK-8 solution (10 μL) was added to each well, and plates were incubated another 4 h. Then absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a Varioskan Flash reader. Culture supernatants were assayed for interleukin-4 (IL-4) using a commercial ELISA.

T cell activation

TDLNs and spleens of mice treated with the combination method of PTT and CpG adjuvant, laser only or without any treatment were isolated at week 1, ground-up, and passed through a cell strainer to form single-cell suspensions. Cells were stained with FITC-conjugated antibodies against CD4 and CD8a as well as APC-conjugated antibodies against CD3, then measured using flow cytometry.

Histopathology examination

Hearts, livers, spleens, lungs, kidneys and tumors of mice treated with the combination method of PTT and CpG adjuvant were harvested at week 1 and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histological analysis. Next, tumor sections at week 1 were immunostained against cleaved caspase-3 (brown), which indicated the process of apoptosis.

Statistical analysis

All results are presented as mean ± SEM and graphed using Graphpad Prism 6.0 (La Jolla, CA, USA). Differences within and between groups were evaluated for significance using, respectively, one-way ANOVA or Student's 2-tailed t test. The threshold of significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results and Discussion

Preparation and characterization of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles

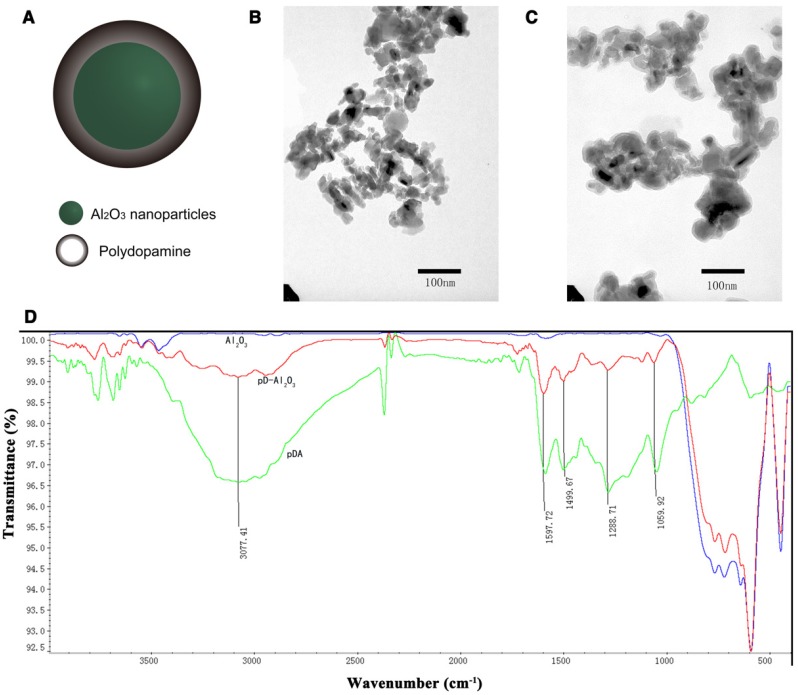

We obtained pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles in a single step within 1 h via dopamine oxidation and self-polymerization (Figure 1A). The average size of the nanoparticles increased from 286.3 ± 4.2 nm to 344.4 ± 5.5 nm with increasing dopamine concentration from 125 to 1,000 μg/mL, while zeta potentials varied from -0.46 ± 0.01 mV to -2.48 ± 0.18 mV (Figure S1A). In all cases, the polydispersity index (PDI) was lower than 0.300; in fact, it was only 0.165 ± 0.011 at a concentration of 1000 μg/mL. The color of the pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles went from clear to black with increasing dopamine concentration from 31.25 μg/mL to 1,000 μg/mL (Figure S1B). Transmission electron microscopy revealed that polydopamine was coated on the surface of Al2O3 nanoparticles, approximately 1.5 nm thick, after 1 h polymerization (Figure 1B-C). Thicker polydopamine layers were obtained with longer polymerization time or higher dopamine concentration.

Figure 1.

Preparation and characterization of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles. (A) Chemical structure of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles. Transmission electron micrographs of (B) Al2O3 nanoparticles and (C) pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles. (D) Fourier-transform IR spectra of Al2O3 nanoparticles (blue trace), pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles (red trace) and polydopamine (pDA, green trace). Relevant peaks are marked and discussed in the text.

FTIR spectroscopy of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles showed the appearance of several peaks between 1,000 and 1,600 cm-1 following dopamine polymerization, and the same peaks were present in the polydopamine reference spectrum (Figure 1D). These peaks indicated successful synthesis of the polydopamine coating 37. The pD-Al2O3 nanoparticle spectrum also contained a peak at 1,059 cm-1, which was assigned to C-OH stretching vibrations, and a peak at 1,288 cm-1, which was assigned to aromatic ring absorption. Peaks at 1,499 and 1,597 cm-1 corresponded to N-H shearing vibrations, while a peak at 3,077 cm-1 was assigned to C-H stretching vibrations. Additionally, we found that pD-Al2O3 and Al2O3 nanoparticles showed similar peaks between 400 and 1,000 cm-1, called the fingerprint region, whereas polydopamine exhibited no obvious peak there, indicating the presence of Al2O3 in our pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles. Next we analyzed the weight percent and atomic percent (%) of four chemical elements (Al, O, C, N) in our Al2O3 and pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles by EDX mapping (Figure S2A). Spectrogram for elements showed that there were more percentages of C and N in our pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles than Al2O3 nanoparticles (Figure S2B-C), confirming the presence of polydopamine. Element mapping indicated the presence of polydopamine and their uniform distribution in pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles (Figure S2D-E).

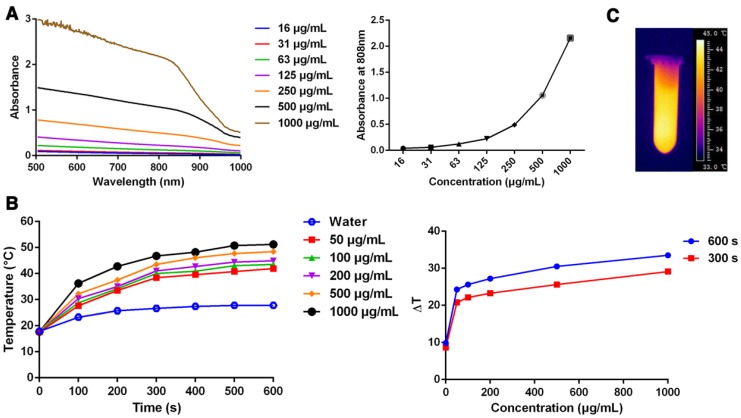

Photothermal performance of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles

We assessed three characteristics of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles in order to evaluate their suitability for PTT 38: appropriate absorption properties in the near-infrared range, photothermal conversion efficiency, and photostability. First, we found that the nanoparticles absorbed broadly in the UV and near-infrared range of wavelengths, and their absorption was much stronger at concentrations from 16 to 1,000 μg/mL (Figure 2A). Absorption in the near-infrared region was strongest at 1,000 μg/mL. In particular, the nanoparticles absorbed strongly at 808 nm, which was the wavelength of the laser that we planned to use for PTT. Secondly, we investigated photothermal conversion by pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles. The temperature of nanoparticle suspensions increased with irradiation time and with dopamine concentration. The temperature of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles at a concentration of 1,000 μg/mL increased by 29.1 ℃ after irradiation for 300 s, while the temperature of deionized water increased by only 3.1 ℃ under the same conditions (Figure 2B). A rapid increase in nanoparticle temperature to over 45.0 ℃ was observed within 5 min using an infrared thermal camera (Figure 2C). Cancer cells can be killed after heating at 42 ℃ for at least 10 min or at temperatures above 50 ℃ for only 5 min 39. Our results suggested that pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles at 1,000 μg/mL initially present in vivo at 36 ℃ could easily be heated to over 50 ℃ within 5 min and efficiently eradicated using an 808 nm laser. We attributed the high photothermal conversion efficiency of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles to their polydopamine coating. Thirdly, we evaluated the photostability of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles at 1,000 μg/mL. No obvious changes in average sizes or zeta potentials were observed after irradiation at 1.18 W/cm2 for 300 s (Figure S1C). In addition, the temperature of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles could reach a similar level after irradiation again at 1.18 W/cm2 for either 300 s or 600 s, compared with the temperature curves after irradiation for the first time in Figure 2B.

Figure 2.

Photothermal performance of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles. (A) UV-visible-near-infrared absorbance spectrum of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles at concentrations from 15.625 to 1,000 μg/mL. The graph on the right shows the absorbance at 808 nm as a function of concentration. (B) Temperature of deionized water or pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles at various concentrations as a function of 808 nm irradiation time from 0 s to 600 s. The graph on the right shows the temperature change (ΔT) of suspensions of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles at various concentrations after 808 nm irradiation for 300 or 600 s. (C) Infrared thermal image of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles at 1,000 μg/mL after 808 nm irradiation for 300 s.

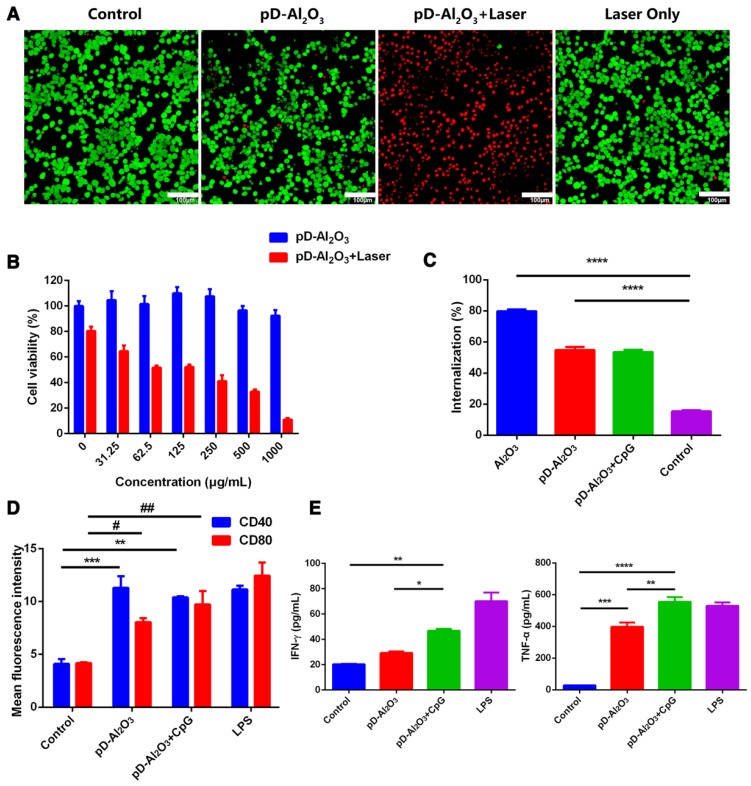

In vitro cytotoxicity, photothermal toxicity and uptake of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles

Given the promising stability and photothermal conversion efficiency of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles, we proceeded to in vitro studies of their ability to kill mouse melanoma B16F10 tumor cells. Exposing cells to laser irradiation alone or to pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles without laser irradiation resulted in negligible cell death, whereas exposing them to the combination of nanoparticles and laser irradiation killed most cells (Figure 3A). These in vitro results suggested that PTT based on 808 nm illumination of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles can efficiently kill cancer cells within 5 min.

Figure 3.

Toxicity, internalization and immunostimulatory activity of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles in vitro. (A) B16F10 cells were incubated with pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles and irradiated (or not) for 5 min with a near-infrared laser operating at 808 nm and 1.18 W/cm2. Cells were then stained with fluorescein diacetate and propidium iodide and examined by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Live cells appear green and dead cells appear red. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Relative viabilities of B16F10 cells after incubation with different concentrations of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles and 5 min irradiation with a near-infrared laser (or not) at 808 nm and 1.18 W/cm2. (C) Efficiency of uptake of lumogallion-stained Al2O3 or pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles by B16F10 cells within 1 h in the presence or absence of CpG. (D) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD40+ or CD80+ expression by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells after treatment with pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles in the presence or absence of CpG. Cells were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) as a positive control, or with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as a negative control. CD40 and CD80 are markers of dendritic cell maturation. (E) Levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α in the supernatants of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells based on ELISA. Results in all panels are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P<0.0001; # P < 0.05; ## P < 0.01.

Next we used the MTT assay to quantitate the cytotoxicity of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles with and without 808 nm irradiation. Incubating B16F10 cells for 24 h without laser irradiation caused minimal impact on cell viability at all nanoparticle concentrations tested (Figure 3B); even at the highest concentration of 1,000 μg/mL, cell viability was approximately 90%. When we repeated these experiments with laser irradiation, cell viability decreased in a nanoparticle concentration-dependent manner, falling to 20% at a concentration of 1,000 μg/mL (Figure 3B).

We used the alum-specific fluorescent dye lumogallion 40 to examine the fate of nanoparticles after addition to B16F10 cultures. The nanoparticles were taken up very efficiently within 1 h (Figure 3C): approximately half of all nanoparticles were internalized regardless of whether CpG was also present in the medium. Uptake was higher in the absence of the polydopamine coating, possibly due to a shielding effect. These results suggested efficient and rapid uptake of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles by B16F10 cells.

Dendritic cell maturation in vitro

Our therapeutic strategy was to inject pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles into tumor allografts in mice, and irradiate the tumors to destroy them and release tumor-associated antigens that could be internalized by immature dendritic cells, then processed and displayed on the surface of mature dendritic cells bound to the major histocompatibility complex. These surface-displayed antigens could then trigger innate and adaptive immunities 41, 42. We examined the feasibility of this strategy in vitro by evaluating whether pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles could stimulate dendritic cell maturation. Incubating BMDCs with pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles led to much higher expression of CD80+ or CD40+ than incubating cells with PBS, albeit lower expression than incubating cells with LPS (Figure 3D). Adding CpG to the medium promoted CD80+ expression. Incubating BMDCs with pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles led to greater IFN-γ and TNF-α secretion, and this further increased in the presence of CpG (Figure 3E). These results suggested that pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles, especially in conjunction with CpG, could stimulate downstream immune responses to boost the efficacy of PTT.

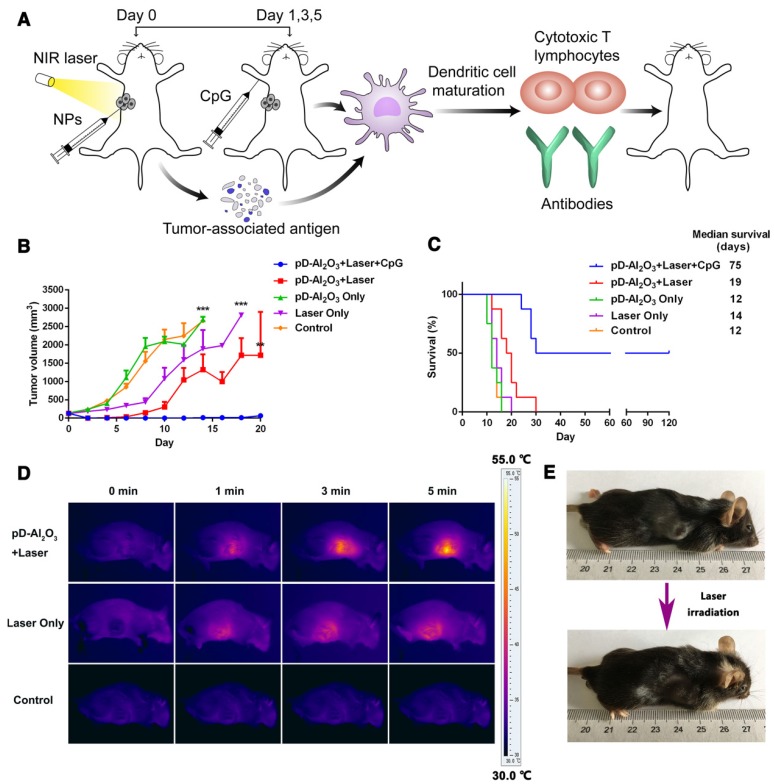

PTT and immunotherapy in vivo

We tested this possibility of combination therapy in vivo by subjecting mice with B16F10 allografts to PTT, which was meant to both destroy tumor tissue in its own right as well as initiate downstream immune responses mediated by mature dendritic cells (Figure 4A). Injecting nanoparticles directly into tumors on day 0 and later CpG subcutaneously on days 1, 3 and 5 led to tumor shrinkage such that tumors were nearly undetectable by day 18 (Figure 4B). In contrast, injecting nanoparticles without CpG inhibited tumor growth during only the first 10 days, demonstrating the important role of the immune adjuvant CpG in triggering strong anti-tumor immune responses. Survival analysis showed that 50% of mice treated with pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles and CpG survived for 120 days, whereas all animals in the other groups died within 10-30 days (Figure 4C). Median survival was 75 days for animals treated with pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles and CpG, and this survival was 3.9- to 6.3-fold longer than for the other groups. These results suggested strong potential for the combination of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles and CpG to inhibit tumor recurrence and metastasis. Mice treated with combination therapy appeared to be in good physical condition. The ability of PTT to increase tumor temperature much better in the presence of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles was confirmed by visual assessment of temperature using an infrared thermal camera (Figure 4D). The tumor temperature in animals injected with pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles reached 55.0 ℃ within 5 min. Meanwhile, mice before and after this treatment were photographed with a digital camera; representative results from one animal are shown in Figure 4E.

Figure 4.

Anti-tumor effects of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles in vivo. (A) Schematic illustration of PTT based on pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles followed by immunotherapy in the presence of CpG. (B) Tumor growth after the indicated treatments (8 mice per group). (C) Survival of mice after the indicated treatments (8 mice per group). (D) Infrared thermal images of mice after intratumor injection of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles and subsequent irradiation for 5 min with a near-infrared laser at 808 nm and 1.18 W/cm2. (E) Photograph of the same mouse before and after 5 min irradiation. These results are representative of eight mice tested.

Nanotechnology is an emerging scientific field that has developed since the 1990s, and a number of nanocarriers targeting malignant tissues have been widely studied for PTT in recent years. When such nanoparticles are delivered to solid tumors via systemic administration, only approximately 0.7% arrive at the tumor 29. Here we bypassed this problem by incorporating intratumor injection into the combination of PTT and immunotherapy. Intratumor injection could ensure 100% distribution of the drug at the tumor site, avoid degradation by first-pass hepatic metabolism, and reduce potential toxicity to other tissues as well as the immune system for safer application. With the combination of near-infrared laser, the local intratumoral temperature contributed to cell damage, while the temperature of surrounding healthy tissues remained at a safe level, demonstrated by simulations that could be applied in future research 43. On the other hand, our findings indicated that, on its own, intratumoral injection of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles followed by PTT only partially suppressed the growth of tumors in vivo, which might be caused by uneven distribution of nanoparticles in the tumor tissues. To ensure more complete tumor eradication, we administered CpG subcutaneously to PTT-treated mice, with the aim of inducing more robust antitumor systemic immunity and inhibiting tumor growth in the long term.

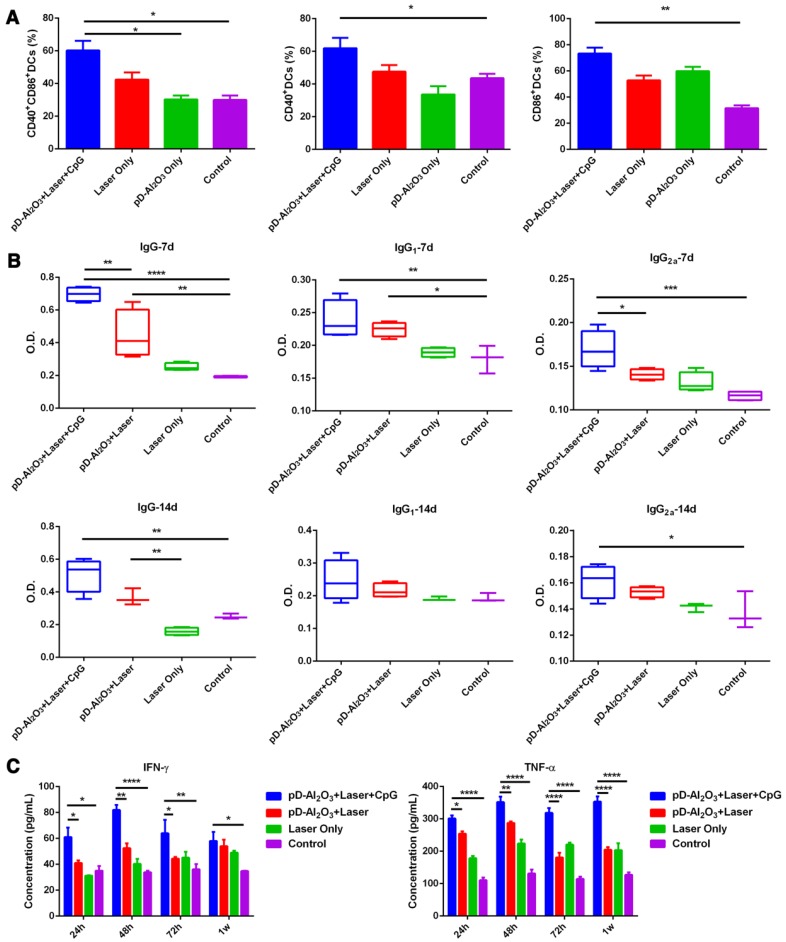

Induction of dendritic cell maturation and immune responses in vivo

Combination treatment of PTT based on pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles and immunotherapy with CpG led to significantly higher expression of CD40+ or CD86+ (gated by CD11c+) within TDLNs (Figure 5A). These results suggested that the combination therapy induced dendritic cell maturation, leading to the secretion of IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a antibodies (Figure 5B). These antibody levels remained higher than the control groups from day 7 to day 14, demonstrating our combination therapy could successfully enhance the humoral immune response of immunized mice. It is generally believed that the IgG1/IgG2a ratio between 0.5 and 2.0 suggests a mixed or balanced response 44, 45, so our combination therapy elicited a quite mixed immune response (Figure S3). PTT-induced dendritic maturation was also associated with increased secretions of TNF-α and IFN-γ 46: treatment with pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles and CpG led to much higher levels of both cytokines at 24 h, 48 h, 72 h and 1 week than the other treatments (Figure 5C). TNF-α, a mediator of cellular immunity, can kill tumor cells directly without harming normal cells, while the Th1 marker IFN-γ regulates immune responses. The ability of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles to induce dendritic cell maturation and cytokine secretion was stronger in the presence of CpG than in its absence, indicating the adjuvant effect of CpG.

Figure 5.

Dendritic cell maturation and production of antibodies and cytokines induced by pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles in vivo. (A) Proportions of dendritic cells expressing CD40 and/or CD86 in tumor-draining lymph nodes after the indicated treatments (gated by CD11c+ cells). CD40 and CD86 are indicators of dendritic cell maturation. (B) Serum levels of IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a from mice on day 7 and day 14 after pD-Al2O3 nanoparticle-based PTT. (C) Serum levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ from mice at 24 h, 48 h, 72 h and 1 week (1w) after pD-Al2O3 nanoparticle-based PTT.

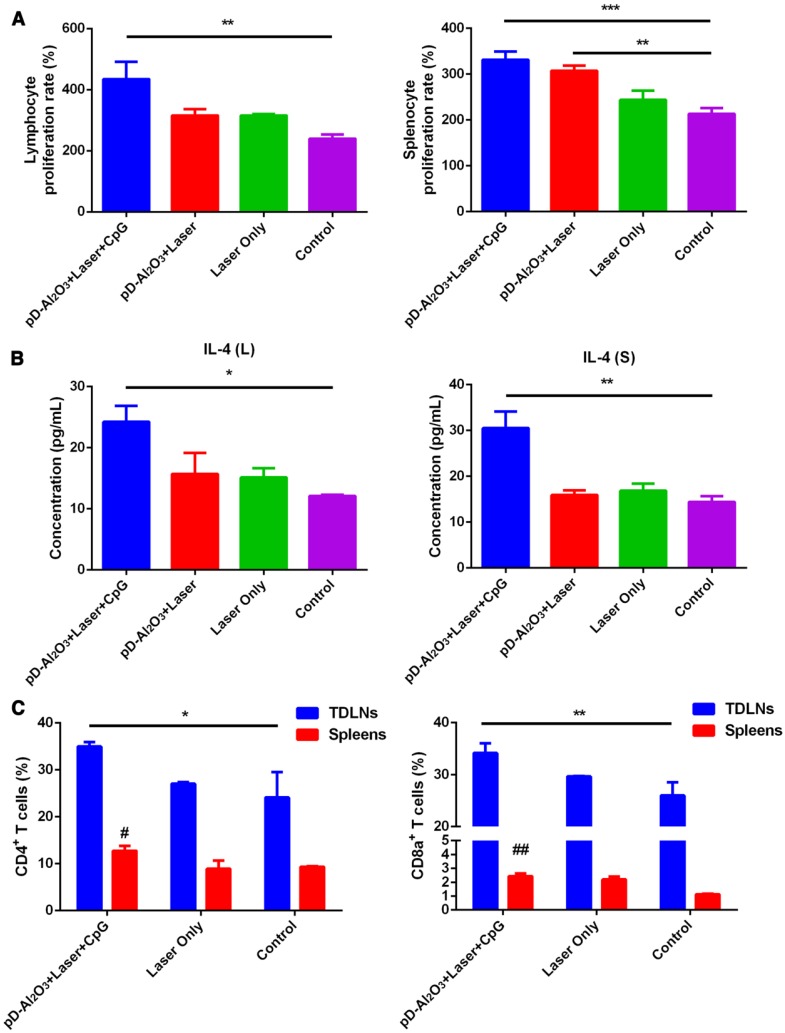

Next we analyzed whether the combination of nanoparticles and CpG could activate and regulate the immune system by examining the proliferation and cytokine secretion of immune cells at 1 week after in vivo treatment. The combination of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles and CpG led to the fastest proliferation of splenocytes and lymphocytes (Figure 6A) and the highest IL-4 secretion by these cells (Figure 6B). Again, these immune responses were stronger in the presence of CpG than in its absence. In addition, the combination of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles and CpG resulted in higher levels of CD8+/CD3+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes and CD4+/CD3+ helper T lymphocytes in TDLNs and spleens than the control group (Figure 6C). Cytotoxic T lymphocytes release perforin, granzymes and granulysin, which kill target cells directly, while helper T lymphocytes regulate adaptive immunity. Together, these various assays revealed the ability of PTT to release tumor-associated antigens that, with the help of adjuvants such as Al2O3 and CpG, could efficiently activate T cells for anti-tumor immunotherapy.

Figure 6.

Various immune responses induced by pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles in vivo. (A) Proliferation rates of lymphocytes and splenocytes from mice after the indicated treatments. (B) Levels of IL-4 in the supernatants of cultures of lymphocytes (L) and splenocytes (S), based on ELISA. (C) Proportions of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes (TDLNs) and spleens of mice after the indicated treatments. Proportions were determined using flow cytometry. Pound signs in panel C indicate P values for comparisons between pD-Al2O3+Laser+CpG and Control using the Student's 2-tailed t test. # P < 0.05; ## P < 0.01.

Adjuvanticity of CpG and Al2O3

Our experiments in vivo showed clearly that the ability of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles to suppress tumor growth and stimulate immune responses effectively depended on co-administration of another adjuvant such as CpG to supplement the adjuvanticity of Al2O3. Comparison of the therapeutic effects of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles in the presence or absence of CpG showed the importance of this adjuvant. CpG is a potent, inexpensive and well-studied adjuvant, which has been used in a hepatitis B vaccine, recently approved for clinical use by the US Food and Drug Administration. We also wanted to confirm that, as intended, the Al2O3 inner core of the nanoparticles was acting as an adjuvant. Therefore, we generated pD-Fe3O4 nanoparticles and investigated their ability to inhibit tumor growth and stimulate immune responses in vivo. These nanoparticles were much weaker than the corresponding Al2O3 nanoparticles at inhibiting tumor growth, stimulating proliferation of splenocytes and lymphocytes, and inducing IL-4 secretion (Figure S4A-D).

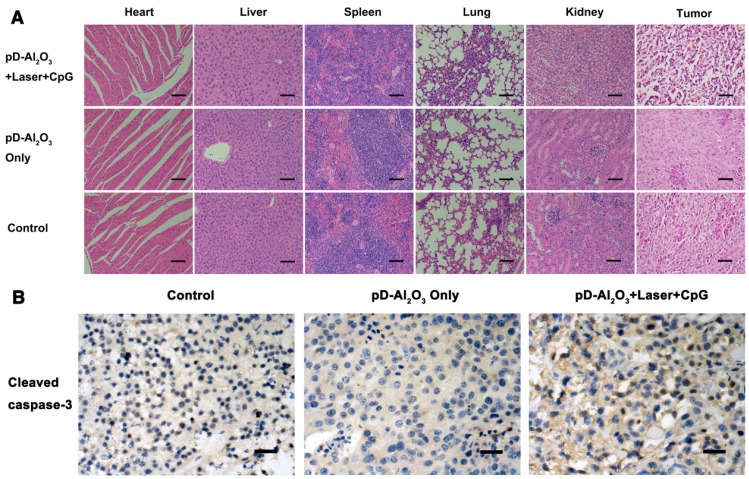

Histopathology examination

Hearts, livers, spleens, lungs and kidneys from mice treated with pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles and CpG were dissected and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Few differences were noted between this group and the control group, except for extensive necrosis in the tumors after pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles-based irradiation plus CpG therapy (Figure 7A). Consistent with this, immunohistochemistry revealed higher levels of cleaved caspase-3 in tumors of mice treated with our combination therapy (Figure 7B), indicating the induction of melanoma cells' apoptosis and necrosis in vivo, thereby inhibiting tumor growth. Furthermore, the combination therapy did not significantly affect mice body weights (Figure S5).

Figure 7.

Histopathology examination. (A) Mice were treated as shown and sections were prepared from heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney and tumor at week 1, then stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) Tumor sections at week 1 were immunostained against cleaved caspase-3 (brown). Scale bar, 50 μm.

Conclusions

Here we have designed a multifunctional platform of pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles for use in the combination of PTT and immunotherapy. We chose to focus on polydopamine as a PTT material because of its good characteristics of photothermal capability, biocompatibility and biodegradation. Polydopamine has several advantages over other PTT materials. For example, it does not persist in the body for long periods unlike gold nanoparticles, it does not induce some toxic responses such as pulmonary inflammation unlike carbon-based nanomaterials, and does not require specific delivery vehicles unlike indocyanine green. pD-Al2O3 nanoparticles between or inside tumor cells absorb near-infrared light, which they convert efficiently into thermal energy to kill tumors in PTT. The Al2O3 within the nanoparticles, together with co-administered CpG, acts as an adjuvant to present tumor-associated antigens to the cell-mediated immune system, triggering robust responses that can help reduce the risk of tumor recurrence. Better understanding of disease biology and advances in translational research are leading to novel modes of cancer therapy, including individualized oncology drugs, targeted drugs and new immunotherapy drugs 47. The combination of PTT and immunotherapy described here may be a useful tool for personalized treatment of cancers. The challenges of cancer monotherapy argue for development of safe and effective combination approaches, and the strategy presented here merits further research.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81673362, 81690261).

Abbreviations

- CCK-8

Cell Counting Kit-8

- BMDCs

bone marrow-derived dendritic cells

- EDX

energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FDA

fluorescein diacetate

- FTIR

fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

- IFN-γ

interferon gamma

- IL-4

interleukin-4

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethyl-thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- pD-Al2O3

polydopamine-aluminum oxide

- PDI

polydispersity index

- PTT

photothermal therapy

- PI

propidium iodide

- TDLNs

tumor-draining lymph nodes

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures.

References

- 1.Yoo D, Lee JH, Shin TH, Cheon J. Theranostic magnetic nanoparticles. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44(10):863–74. doi: 10.1021/ar200085c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bardhan R, Lal S, Joshi A, Halas NJ. Theranostic nanoshells: from probe design to imaging and treatment of cancer. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44(10):936–46. doi: 10.1021/ar200023x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao Y, Wu X, Zhou L, Su Y, Dong CM. A sweet polydopamine nanoplatform for synergistic combination of targeted chemo-photothermal therapy. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2015;36(10):916–22. doi: 10.1002/marc.201500090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Q, Liu X, Zeng J, Cheng Z, Liu Z. Albumin-NIR dye self-assembled nanoparticles for photoacoustic pH imaging and pH-responsive photothermal therapy effective for large tumors. Biomaterials. 2016;98:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X, Li H, Liu X, Tian Y, Guo H, Jiang T. et al. Enhanced photothermal therapy of biomimetic polypyrrole nanoparticles through improving blood flow perfusion. Biomaterials. 2017;143:130–41. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He C, Duan X, Guo N, Chan C, Poon C, Weichselbaum RR. et al. Core-shell nanoscale coordination polymers combine chemotherapy and photodynamic therapy to potentiate checkpoint blockade cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12499. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gobin AM, Lee MH, Halas NJ, James WD, Drezek RA, West JL. Near-infrared resonant nanoshells for combined optical imaging and photothermal cancer therapy. Nano Lett. 2007;7(7):1929–34. doi: 10.1021/nl070610y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng Y, Zhang D, Wu M, Liu Y, Zhang X, Li L. et al. Lipid-AuNPs@PDA nanohybrid for MRI/CT imaging and photothermal therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6(16):14266–77. doi: 10.1021/am503583s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu KW, Huang CC, Hwu JR, Su WC, Shieh DB, Yeh CS. A new photothermal therapeutic agent: core-free nanostructured Au x Ag1-x dendrites. Chemistry. 2008;14(10):2956–64. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang S, Chen M, Zheng N. Sub-10-nm Pd nanosheets with renal clearance for efficient near-infrared photothermal cancer therapy. Small. 2014;10(15):3139–44. doi: 10.1002/smll.201303631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang C, Diao S, Wang C, Gong H, Liu T, Hong G. et al. Tumor metastasis inhibition by imaging-guided photothermal therapy with single-walled carbon nanotubes. Adv Mater. 2014;26(32):5646–52. doi: 10.1002/adma.201401825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma Y, Tong S, Bao G, Gao C, Dai Z. Indocyanine green loaded SPIO nanoparticles with phospholipid-PEG coating for dual-modal imaging and photothermal therapy. Biomaterials. 2013;34(31):7706–14. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Q, Liang C, Wang X, He J, Li Y, Liu Z. An albumin-based theranostic nano-agent for dual-modal imaging guided photothermal therapy to inhibit lymphatic metastasis of cancer post surgery. Biomaterials. 2014;35(34):9355–62. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang P, Rong P, Jin A, Yan X, Zhang MG, Lin J. et al. Dye-loaded ferritin nanocages for multimodal imaging and photothermal therapy. Adv Mater. 2014;26(37):6401–8. doi: 10.1002/adma.201400914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu D, Zhang J, Gao G, Sheng Z, Cui H, Cai L. Indocyanine Green-Loaded Polydopamine-Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposites with Amplifying Photoacoustic and Photothermal Effects for Cancer Theranostics. Theranostics. 2016;6(7):1043–52. doi: 10.7150/thno.14566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang Q, Luo Z, Men Y, Yang P, Peng H, Guo R. et al. Red blood cell membrane-camouflaged melanin nanoparticles for enhanced photothermal therapy. Biomaterials. 2017;143:29–45. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon JD. Spectroscopic and dynamic studies of the epidermal chromophores trans-urocanic acid and eumelanin. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33(5):307–13. doi: 10.1021/ar970250t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Ai K, Liu J, Deng M, He Y, Lu L. Dopamine-melanin colloidal nanospheres: an efficient near-infrared photothermal therapeutic agent for in vivo cancer therapy. Adv Mater. 2013;25(9):1353–9. doi: 10.1002/adma.201204683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Ai K, Lu L. Polydopamine and its derivative materials: synthesis and promising applications in energy, environmental, and biomedical fields. Chem Rev. 2014;114(9):5057–115. doi: 10.1021/cr400407a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong Z, Gong H, Gao M, Zhu W, Sun X, Feng L. et al. Polydopamine Nanoparticles as a Versatile Molecular Loading Platform to Enable Imaging-guided Cancer Combination Therapy. Theranostics. 2016;6(7):1031–42. doi: 10.7150/thno.14431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liebscher J, Mrowczynski R, Scheidt HA, Filip C, Hadade ND, Turcu R. et al. Structure of polydopamine: a never-ending story? Langmuir. 2013;29(33):10539–48. doi: 10.1021/la4020288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu X, Cao J, Li H, Li J, Jin Q, Ren K. et al. Mussel-inspired polydopamine: a biocompatible and ultrastable coating for nanoparticles in vivo. ACS Nano. 2013;7(10):9384–95. doi: 10.1021/nn404117j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee H, Dellatore SM, Miller WM, Messersmith PB. Mussel-inspired surface chemistry for multifunctional coatings. Science. 2007;318(5849):426–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1147241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park J, Brust TF, Lee HJ, Lee SC, Watts VJ, Yeo Y. Polydopamine-based simple and versatile surface modification of polymeric nano drug carriers. ACS Nano. 2014;8(4):3347–56. doi: 10.1021/nn405809c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin LS, Cong ZX, Cao JB, Ke KM, Peng QL, Gao J. et al. Multifunctional Fe(3)O(4)@polydopamine core-shell nanocomposites for intracellular mRNA detection and imaging-guided photothermal therapy. ACS Nano. 2014;8(4):3876–83. doi: 10.1021/nn500722y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Li Y, Jiao J, Hu HM. Alpha-alumina nanoparticles induce efficient autophagy-dependent cross-presentation and potent antitumour response. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6(10):645–50. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flach TL, Ng G, Hari A, Desrosiers MD, Zhang P, Ward SM. et al. Alum interaction with dendritic cell membrane lipids is essential for its adjuvanticity. Nat Med. 2011;17(4):479–87. doi: 10.1038/nm.2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Q, Xu L, Liang C, Wang C, Peng R, Liu Z. Photothermal therapy with immune-adjuvant nanoparticles together with checkpoint blockade for effective cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13193. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilhelm S, Tavares AJ, Dai Q, Ohta S, Audet J, Dvorak HF. et al. Analysis of nanoparticle delivery to tumours. Nat Rev Mater. 2016;1(5):16014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang C, Xu L, Liang C, Xiang J, Peng R, Liu Z. Immunological responses triggered by photothermal therapy with carbon nanotubes in combination with anti-CTLA-4 therapy to inhibit cancer metastasis. Adv Mater. 2014;26(48):8154–62. doi: 10.1002/adma.201402996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lou Y, Liu C, Lizee G, Peng W, Xu C, Ye Y. et al. Antitumor activity mediated by CpG: the route of administration is critical. J Immunother. 2011;34(3):279–88. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31820d2a05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Titta A, Ballester M, Julier Z, Nembrini C, Jeanbart L, van der Vlies AJ. et al. Nanoparticle conjugation of CpG enhances adjuvancy for cellular immunity and memory recall at low dose. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(49):19902–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313152110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leroux-Roels G. Old and new adjuvants for hepatitis B vaccines. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2015;204(1):69–78. doi: 10.1007/s00430-014-0375-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell JD. Development of the CpG Adjuvant 1018: A Case Study. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1494:15–27. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6445-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nierkens S, den Brok MH, Roelofsen T, Wagenaars JA, Figdor CG, Ruers TJ. et al. Route of administration of the TLR9 agonist CpG critically determines the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy in mice. PLoS One. 2009;4(12):e8368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas SN, Vokali E, Lund AW, Hubbell JA, Swartz MA. Targeting the tumor-draining lymph node with adjuvanted nanoparticles reshapes the anti-tumor immune response. Biomaterials. 2014;35(2):814–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mondin G, Wisser FM, Leifert A, Mohamed-Noriega N, Grothe J, Dorfler S. et al. Metal deposition by electroless plating on polydopamine functionalized micro- and nanoparticles. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2013;411:187–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2013.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tian Y, Zhang J, Tang S, Zhou L, Yang W. Polypyrrole Composite Nanoparticles with Morphology-Dependent Photothermal Effect and Immunological Responses. Small. 2016;12(6):721–6. doi: 10.1002/smll.201503319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Habash RW, Bansal R, Krewski D, Alhafid HT. Thermal therapy, part 1: an introduction to thermal therapy. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2006;34(6):459–89. doi: 10.1615/critrevbiomedeng.v34.i6.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mold M, Shardlow E, Exley C. Insight into the cellular fate and toxicity of aluminium adjuvants used in clinically approved human vaccinations. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31578. doi: 10.1038/srep31578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levitz SM, Golenbock DT. Beyond empiricism: informing vaccine development through innate immunity research. Cell. 2012;148(6):1284–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang H, Wang Q, Sun X. Lymph node targeting strategies to improve vaccination efficacy. J Control Release. 2017;267:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dimitriou NM, Tsekenis G, Balanikas EC, Pavlopoulou A, Mitsiogianni M, Mantso T. et al. Gold nanoparticles, radiations and the immune system: Current insights into the physical mechanisms and the biological interactions of this new alliance towards cancer therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2017;178:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiang ZQ, Gao GP, Reyes-Sandoval A, Li Y, Wilson JM, Ertl HC. Oral vaccination of mice with adenoviral vectors is not impaired by preexisting immunity to the vaccine carrier. J Virol. 2003;77(20):10780–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.20.10780-10789.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xie Z, Ji Z, Zhang Z, Gong T, Sun X. Adenoviral vectors coated with cationic PEG derivatives for intravaginal vaccination against HIV-1. Biomaterials. 2014;35(27):7896–908. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Borchers S, Masslo C, Muller CA, Tahedl A, Volkind J, Nowak Y. et al. Detection of ABCB5-tumour-antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in Melanoma Patients and Implications for Immunotherapy. Clin Exp Immunol. 2018;191(1):74–83. doi: 10.1111/cei.13053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen H, Zhang W, Zhu G, Xie J, Chen X. Rethinking cancer nanotheranostics. Nat Rev Mater. 2017;2:17024. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2017.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures.