Introduction

Although there are a growing number of racial and ethnic minorities in the United States(US), they are underrepresented in research [1]. In dementia trials it is estimated that the, overall minority participation rate is less than 5% [1]. Within the next five decades minorities will be disproportionately represented in the older age groups most at risk for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [2] [3]. Creating parity in research participation for minorities is important to allow generalizability of research findings and equity in the provision of health care [1]. Identifying barriers to participation among minority populations, especially Latinos, the largest and fastest growing minority group in the US, will allow for better recruitment and retention.

Barriers to minority participation in clinical research [1] identified shared and discrete barriers that affect minority groups such as African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders, included: mistrust of the medical establishment and medical research, financial constraints relating to the competing demands of work, lack of information about research opportunities, as well as privacy and confidentiality concerns [1, 4]. Others have shown that compared to Caucasians, Latino participants are suspicious about research if they do not have a prior relationship with the researchers [5].

Although barriers to participation can be significant for minorities, self-reported willingness to participate in research was comparable among minority groups and Caucasian participants [6]. In one study of willingness to participate in cancer research, only 48% of Latinos approached knew what a clinical trial was [7]. However after an explanation, 65% indicated they would consider participation.

The Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (MSADRC) in New York City is adjacent to a diverse community of over 111,000 residents of whom 55% are Latino and 33% are African American. The percent of individuals living below the poverty level is nearly twice as high as those living in other parts of the city. In an effort to increase the number of minorities enrolled at the MSADRC, outreach strategies such as community-based talks and screenings, home visits, as well as hiring coordinators with similar backgrounds have been implemented. These long-standing strategies have been successful in maintaining minority participation at over 25%. Anecdotal experience suggests that strong ongoing presence in the community coupled with sensitivity to community beliefs about aging, cognition and research, are important to minority participation.

Jefferson et al. [8] developed a Research Attitudes Questionnaire (RAQ), which was used in an active observational cohort to understand barriers to enrolling in clinical trials. This sample (78% white, mean of 16.2 years of education) was participating in longitudinal research. We used the 7-item subset of the RAQ [9] to assess attitudes of the elderly in an urban minority community to understand our community and to identify areas to include in outreach talks concerning research. We examined how participant characteristics, such as age, years in the US and education related to research attitudes. This project was undertaken to refine the educational programming of the Outreach, Recruitment and Education Core, and the NY state funded Alzheimer’s Disease Assistance Center.

Methods

Community talks on cognitive aging and AD, specifically normal changes with age, signs and symptoms of dementia etc., were given at senior centers in English and Spanish. At the end of the talks, attendees were asked if they would be willing to fill in a short questionnaire. The RAQ-7 was administered to 123 elderly attendees to evaluate our approach in engaging this population. Data was anonymous and no health information was collected; our IRB confirmed that approval was not required. All respondents were self-reported minorities. The questionnaire was translated into Spanish to include monolingual Spanish-speakers. Attendees answered seven questions on a 5-point Likert Scale (1=Strongly disagree, through 5=Strongly agree), to assess attitudes towards research and research participation (see supplemental Table 1 for questions.) Anonymous information collected included: age, education, years in the US, and country of origin. Statistical comparisons were made to Jefferson’s published sample of 235 subjects[8].

Results

The sample consisted of 123 responders: mean age of 72.6 (+/− 8.9), 10.2 (+/− 4) years of education, and 66% born outside of the mainland US, representing 14 different countries, with 43% from Puerto Rico. Thirty-two percent reported an 8th grade level of education or less. T-tests were used to assess associations between research attitudes, and each of the following: age (<70 vs. >=70), level of education (<=12 vs. >12), if born outside mainland US, years in the US (<=30 vs. >30) and language used for the questionnaire (English vs. Spanish). The only significant differences were seen in those who had been in the US for <30 years, who reported slightly more favorable responses on three items which reflected general hopefulness concerning the efficacy of research, and responsibility to participate. Of note only 17 of the 82 individuals born outside of the continental US had been in the country for < 30 years.

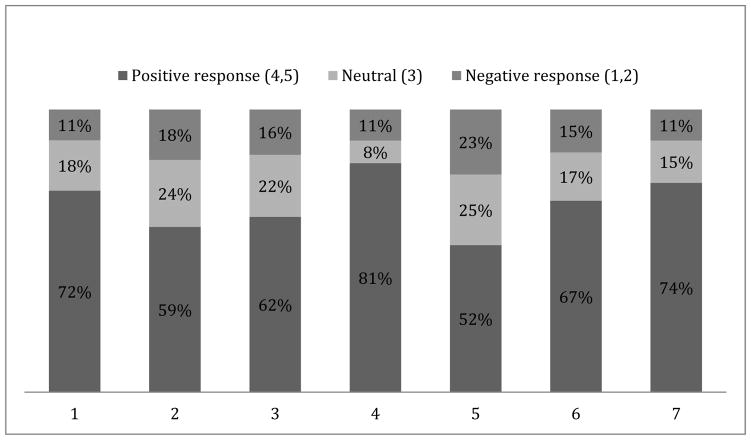

The responders demonstrated mildly positive attitudes towards research. The aggregate mean was 3.7 (SD=0.9). A positive response was defined as a 4 (“Agree”) or 5 (“Strongly agree”). Seventy-two percent chose a positive response on question 1 (“I have a positive view about medical research in general”) and 81% did on question 4 (“Society needs to devote more resources to medical research”). (See Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Mount Sinai Group Percentages for Each Question

In response to (Figure 1), question 2: “Medical researchers can be trusted to protect the interest of people who take part in their research studies”, 42% gave neutral or negative responses., and in response to question 5: “Participating in medical research is generally safe” 48% gave neutral or negative responses. (Figure 1).

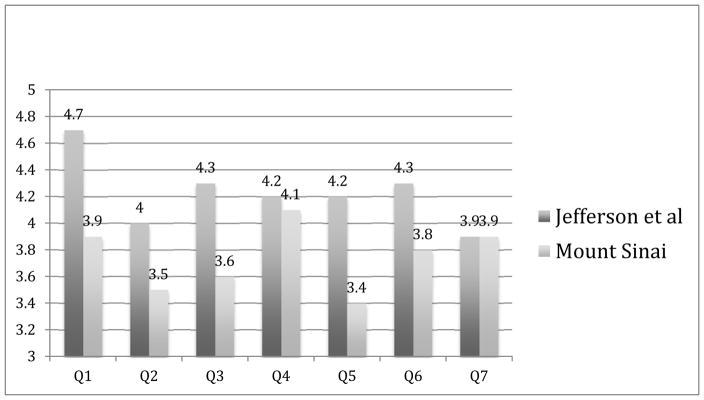

Although the mean of each of the seven items was mildly positive (i.e higher than neutral: 3.0), they were significantly lower than those reported by Jefferson’s [8] (p < .0001), except on questions 4 (about resources) and 7 (potential for research success) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of RAQ Question Means between Jefferson and Moount Sinai Respondents

Discussion

Attitudes toward research in a community-based minority urban population were explored, and compared to a published, predominantly white, sample of longitudinal research participants. In our sample overall attitudes towards clinical research were positive. A significant minority of responders endorsed neutral or negative attitudes regarding perceived safety of research and trust of investigators. Our data is consistent with the literature that minorities are more likely to be mistrustful of medical research [1].

These results for trustworthiness and safety were notable in light of Jefferson’s published means [8]. Our group was significantly less positive than the primarily well-educated, predominantly white participants enrolled in longitudinal research in the Jefferson sample. Depending on the question, 11–23% of our group endorsed frankly negative views particularly concerning safety (23%) and trust (18%).

Both cohorts [8] were similar regarding allocation of resources for research and whether cures will be found, indicating a generally favorable attitude towards research. Respondents who had been in the US for <30 years had a statistically more favorable view of research in general than those who had been here for longer, but it is unclear whether this is a genuine cohort issue or related to sampling bias, as only 17 out of 82 born outside the continental US had been in the country for <30 years.

These results highlight that even in a community with generally positive attitudes toward research, mistrust and concerns about safety persist and may be barriers to participation. Our data underscores the need to build trust through health communication strategies that encourage open dialogue.

In our ADRC, 38.5% of participants are minorities in contrast to the 2012 National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center numbers (13.9 Black and 7.9 Hispanic). There may be overlap between these groups as one is coded as race and the other as ethnicity. To sustain this high level of minority recruitment, we have identified strategies to engage and sustain minority elders and caregivers in research. For example, we hire staff members of similar cultural background and work with community collaborators as outreach partners. We have established a community advisory board to facilitate the creation of culturally relevant materials and programs. These approaches have been explored by other researchers [10–12].

There are several limitations of our report. While all participants were either Latino or African American, we did not have a demographic item regarding specific breakdown of race/ethnicity. Secondly, our comparison to Jefferson’s sample is limited by the fact that their participants were engaged in observational research, and thus might be expected to have more positive views about research than our community members.

Future research might include qualitative outreach methods such as community-based focus groups that explore concerns around mistrust and safety. To isolate the variables of race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status and current research participation, the RAQ could either be given to longitudinal minority/non-minority participants across the spectrum of cognitive impairments, or to non-minority community based individuals.

Historically, poor urban community residents have not been comfortable with research or interested in participation. These results are encouraging because of the overall positive attitude toward research within the community, setting the stage for targeted interventions to address trust and safety within this positive framework.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ichan School of Medicine, The Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC: U01 P50 AG005138) and the New York State Alzheimer’s Disease Assistance Center at Mount Sinai (ADAC: C020360)

References

- 1.George S, Duran N, Norris K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among african americans, latinos, asian americans, and pacific islanders. American journal of public health. 2014;104:e16–31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valle R, Lee B. Research priorities in the evolving demographic landscape of Alzheimer disease and associated dementias. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2002;16(Suppl 2):S64–76. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200200002-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang MX, Stern Y, Marder K, Bell K, Gurland B, Lantigua R, Andrews H, Feng L, Tycko B, Mayeux R. The APOE-epsilon4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer disease among African Americans, whites, and Hispanics. JAMA. 1998;279:751–755. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.10.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Racial differences in factors that influence the willingness to participate in medical research studies. Annals of epidemiology. 2002;12:248–256. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallagher-Thompson D, Singer LS, Depp C, Mausbach BT, Cardenas V, Coon DW. Effective recruitment strategies for Latino and Caucasian dementia family caregivers in intervention research. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry: official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2004;12:484–490. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.12.5.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katz RV, Kegeles SS, Kressin NR, Green BL, Wang MQ, James SA, Russell SL, Claudio C. The Tuskegee Legacy Project: willingness of minorities to participate in biomedical research. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. 2006;17:698–715. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallington SF, Luta G, Noone AM, Caicedo L, Lopez-Class M, Sheppard V, Spencer C, Mandelblatt J. Assessing the awareness of and willingness to participate in cancer clinical trials among immigrant Latinos. Journal of community health. 2012;37:335–343. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9450-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jefferson AL, Lambe S, Chaisson C, Palmisano J, Horvath KJ, Karlawish J. Clinical research participation among aging adults enrolled in an Alzheimer’s Disease Center research registry. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD. 2011;23:443–452. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubright JD, Cary MS, Karlawish JH, Kim SY. Measuring how people view biomedical research: Reliability and validity analysis of the Research Attitudes Questionnaire. Journal of empirical research on human research ethics: JERHRE. 2011;6:63–68. doi: 10.1525/jer.2011.6.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Bryant SE, Johnson L, Balldin V, Edwards M, Barber R, Williams B, Devous M, Cushings B, Knebl J, Hall J. Characterization of Mexican Americans with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD. 2013;33:373–379. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-121420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grill JD, Galvin JE. Facilitating Alzheimer disease research recruitment. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2014;28:1–8. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hinton L, Carter K, Reed BR, Beckett L, Lara E, DeCarli C, Mungas D. Recruitment of a community-based cohort for research on diversity and risk of dementia. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2010;24:234–241. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181c1ee01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.