Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the biodistribution, metabolism, and pharmacokinetics of a new type I collagen–targeted magnetic resonance (MR) probe, CM-101, and to assess its ability to help quantify liver fibrosis in animal models.

Materials and Methods

Biodistribution, pharmacokinetics, and stability of CM-101 in rats were measured with mass spectrometry. Bile duct–ligated (BDL) and sham-treated rats were imaged 19 days after the procedure by using a 1.5-T clinical MR imaging unit. Mice were treated with carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) or with vehicle two times a week for 10 weeks and were imaged with a 7.0-T preclinical MR imaging unit at baseline and 1 week after the last CCl4 treatment. Animals were imaged before and after injection of 10 µmol/kg CM-101. Change in contrast-to-noise ratio (ΔCNR) between liver and muscle tissue after CM-101 injection was used to quantify liver fibrosis. Liver tissue was analyzed for Sirius Red staining and hydroxyproline content. The institutional subcommittee for research animal care approved all in vivo procedures.

Results

CM-101 demonstrated rapid blood clearance (half-life = 6.8 minutes ± 2.4) and predominately renal elimination in rats. Biodistribution showed low tissue gadolinium levels at 24 hours (<3.9% injected dose [ID]/g ± 0.6) and 10-fold lower levels at 14 days (<0.33% ID/g ± 12) after CM-101 injection with negligible accumulation in bone (0.07% ID/g ± 0.02 and 0.010% ID/g ± 0.004 at 1 and 14 days, respectively). ΔCNR was significantly (P < .001) higher in BDL rats (13.6 ± 3.2) than in sham-treated rats (5.7 ± 4.2) and in the CCl4-treated mice (18.3 ± 6.5) compared with baseline values (5.2 ± 1.0).

Conclusion

CM-101 demonstrated fast blood clearance and whole-body elimination, negligible accumulation of gadolinium in bone or tissue, and robust detection of fibrosis in rat BDL and mouse CCl4 models of liver fibrosis.

© RSNA, 2017

See also the editorial by Pomper and Lee in this issue.

Introduction

The incidence of chronic liver disease is increasing worldwide and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality (1,2). Chronic liver disease is induced by repeated hepatic injury resulting in tissue fibrosis, marked by the accumulation of extracellular matrix components rich in fibrillar collagen (3). Alcohol excess, hepatitis B or C infection, fatty liver disease, diabetes, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and metabolic dysfunction have all been shown to lead to liver fibrosis (4). Unchecked fibrosis eventually leads to disruption of normal tissue architecture and function, cirrhosis, and in some patients, the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (5,6). However, if the underlying cause of disease is successfully treated, liver fibrosis has the potential to regress or even reverse to a normal liver architecture (7,8). Therefore, methods to accurately assess fibrosis stage and evaluate early responses to potential therapies are crucial for determining prognosis and guiding therapeutic strategies.

Biopsy remains the reference standard for assessing liver fibrosis but suffers from numerous problems, including intra- and interobserver variability, medical complications (9,10), and sampling errors due to the small amount of tissue sampled (11). Furthermore, repeated biopsies to evaluate disease progression or response to treatment are impractical because of the increased risk of complications and poor patient compliance. Noninvasive strategies that can repeatedly assess liver fibrosis throughout the entire organ are therefore needed to assess disease stage and monitor treatment response (12).

Type I collagen is a major component of fibrotic tissue and increases with fibrosis progression. Its extracellular location makes collagen readily accessible to a molecular probe, and, in fibrosis, collagen is present at concentrations detectable by magnetic resonance (MR) probes. Previous studies with the type I collagen–targeted molecular MR probe EP-3533 have demonstrated its ability to help stage liver fibrosis and assess response to antifibrotic therapies with high sensitivity and specificity in several rodent models (13–17). However, EP-3533 used the linear gadopentetate dimeglumine (Gd-DTPA) chelate, which results in some retention of gadolinium in bone and other tissue (13,15), making this compound unsuitable for clinical translation owing to the risk of gadolinium-associated nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (18). Here, we report a probe, CM-101, which uses the same collagen-targeting mechanism but employs the much more stable macrocycle gadoterate meglumine (Gd-DOTA) chelate. We evaluated its biodistribution, metabolism, and pharmacokinetics in rats and validated its ability to depict liver fibrosis in two different rodent models imaged at two independent sites.

Materials and Methods

Collagen-targeted Molecular Probe

CM-101 comprises a 17-amino-acid peptide, with a 10-amino-acid disulfide bridged cyclic core, conjugated to three Gd-DOTA moieties through amide linkages. The peptide was synthesized by using conventional solid-phase techniques, and then three t-butyl–protected DOTA chelators were coupled by using standard coupling chemistry. After acid deprotection of the t-butyl groups, the molecule was reacted with gadolinium chloride, and the resultant complex was purified at high-performance liquid chromatography. CM-101 was characterized for purity and identity by using high-performance liquid chromatography, mass spectrometry, and elemental analysis. The longitudinal (r1) and transverse (r2) relaxivities of CM-101 were measured at 1.5- and 3.0-T field strengths in pH-7.4 phosphate-buffered saline. The affinity of CM-101 to human, dog, and rat type I collagens has not previously been reported and was assessed by incubating increasing concentrations of the probe with type I collagen immobilized on a well plate or in a blank well for 2 hours, similar to a method described previously (13). Gadolinium concentration was measured in the blank well (total) and in the collagen-containing well (unbound). The difference in concentration gives the concentration bound to collagen. A plot of bound versus unbound was fit to a multisite-binding isotherm to obtain dissociation constants.

CM-101 Biodistribution, Blood Plasma Clearance, and Stability in Rats

The biodistribution of gadolinium after intravenous injection of 10 μmol CM-101 per kilogram of body weight was measured with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry of ex vivo rat tissue harvested at 1 and 14 days after injection. Rat blood plasma was sampled over a 2-hour time period after CM-101 injection, and the samples were analyzed with high-performance liquid chromatography/inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry to quantify CM-101 and any metabolites.

Animal Models of Liver Fibrosis

All animal experiments and procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Liver fibrosis was induced in eight male CD rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, Mass) by ligating the common bile duct; this was termed the bile duct–ligated (BDL) model. Control animals (n = 11) underwent a sham procedure. Rats were imaged 19 days after surgery.

Liver fibrosis was induced in C57BL6 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Me) by treatment with 0.4 μL/g carbon-tetrachloride (CCl4) (n = 12) in a 1:5 CCl4:olive oil mixture, administered by means of intraperitoneal injection twice per week for 10 weeks. Control animals were treated with vehicle (olive oil) (n = 3). A total of 15 mice were used for this study, with 12 treated with CCl4 ane three given vehicle. A subset of mice (n = 11) was imaged at baseline prior to the start of treatment. Four of the CCl4-treated mice did not survive to the end of the study. All surviving mice were imaged 1 week after the last treatment (CCl4: n = 8; vehicle: n = 3). Of the eight CCl4-treated mice that survived to the end of the study, four of these were part of the baseline imaging group.

MR Imaging

The rat BDL and mouse CCl4 models of liver fibrosis were imaged at different sites by different MR imaging physicists (C.T.F., an MR imaging physicist with 15 years of experience, performed the BDL rat study; R.K., an MR imaging physicist with 25 years of experience, performed the CCl4 mouse study). Rats were imaged with a 1.5-T clinical MR imaging unit (Siemens Healthcare, Malvern, Pa) by using a home-built transmit-receive solenoid coil. Animals were anesthetized with 1%–2% isoflurane, and respiration rate was monitored with a small-animal physiologic monitoring system (SA Instruments, Stony Brook, NY). Respiratory gated three-dimensional inversion-recovery fast low-angle shot (FLASH) images were acquired before and continuously for up to 30 minutes after intravenous injection of 10 μmol/kg CM-101. A nonselective inversion pulse was used with an inversion recovery time of 250 msec. Image acquisition parameters consisted of an echo time of 2.44 msec, a field of view of 120 × 93 mm, a matrix of 192 × 150 (0.625-mm in-plane resolution), a section thickness of 0.6 mm, and 36 image sections. A segmented k-space acquisition method consisting of 51 segments was used to reduce the acquisition time (total acquisition time: 2.1 minutes). The effective repetition time was dictated by the respiration rate. Anesthesia was adjusted to maintain a respiration rate of 60 breaths per minute ± 5 for an effective repetition time of 1000 msec ± 90. For generating R1 relaxation rate maps, a series of three-dimensional inversion-recovery FLASH images were also acquired before and 30 minutes after CM-101 administration with inversion recovery times of 50, 100, 200, 250, 300, 400, and 1000 msec.

Mice were imaged with a 7.0-T preclinical small-animal MR imaging unit (Bruker Biospin, Billerica, Mass) and a quadrature birdcage volume coil with a 5-cm diameter. Animals were anesthetized with 1%–2% isoflurane. Ungated T1-weighted rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement (RARE) images were acquired before and continuously for up to 30 minutes after intravenous injection of 10 μmol/kg CM-101. Image acquisition parameters consisted of a spin-echo time of 4.5 msec, a RARE factor of eight, a repetition time of 600 msec, a field of view of 45 × 45 mm, a matrix of 128 × 64, a section thickness of 1.5 mm, and eight image sections (total acquisition time, 29 seconds).

After imaging, animals were sacrificed, and liver tissue was taken for analysis. The liver contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) was calculated as the difference in signal-to-noise ratio between liver and muscle regions of interest. The time dependence of the change in CNR (ΔCNR) following contrast agent injection was determined from the dynamic MR images. The difference between the time-dependent ΔCNR data in diseased and control animals was calculated and used to determine the optimal imaging time point where the maximal difference in ΔCNR is observed. The area under the ΔCNR curve (AUC) was also calculated. The AUC and the ΔCNR at the optimal imaging time point were both used as quantitative markers of fibrosis. For rats, longitudinal relaxation rate (R1) maps were generated from a series of inversion-recovery images by using a custom written Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, Mass) program for voxelwise fitting of the inversion-recovery signal intensities as a function of the inversion recovery time. Two MR physicists who were blinded to the study performed the data analysis (C.T.F., an MR imaging physicist with 15 years of experience, performed BDL rat analysis; and R.K., an MR imaging physicist with 25 years of experience, performed CCl4 mouse analysis).

Ex Vivo Tissue Analysis

Formalin-fixed samples were embedded in paraffin, cut into 5-μm-thick slices, and stained with Sirius Red according to standard procedures. Sirius Red–stained sections were analyzed by a liver pathologist (R.M., with 6 years of experience), who was blinded to the study, to score the amount of fibrosis according to the method of Ishak et al (19). In addition, the collagen proportional area (CPA), as determined by the percentage area stained with Sirius Red, was quantified from the histologic images by using ImageJ (13–15,20). Hydroxyproline in tissue was quantified with high-performance liquid chromatography analysis of tissue acid digests (21). Hydroxyproline is expressed as amount per wet weight of tissue.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by using Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, Calif) and R (version 3.2.2) with the name and lme4 packages, with P < .05 considered to indicate a significant difference. Differences in CPA, hydroxyproline, AUC, and ΔCNR at a fixed time point between groups were tested with the Welch unpaired t test. Differences in Ishak score were tested with a Mann-Whitney test. For analysis of the mouse CCl4 data, in which some mice were imaged at both the baseline and 10-week time points, a linear mixed-effects model that included a random term to account for the correlations between observations from the same mouse was used to compare the baseline and 10-week CCI4 mice. Correlations between CPA and MR imaging metrics (ΔCNR AUC, ΔCNR) and between hydroxyproline and MR imaging metrics (ΔCNR AUC, ΔCNR) of fibrosis were assessed with the Pearson correlation coefficient.

Results

Relaxivity of CM-101 and Binding to Collagen

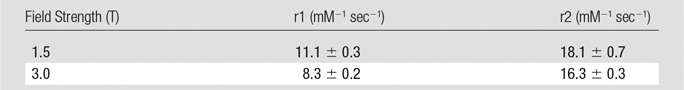

The longitudinal relaxivity of CM-101, expressed on a per-gadolinium basis, in pH 7.4 phosphate-buffered saline at 37°C was r1 = 11.1 ± 0.3 at 1.5 T and r1 = 8.3 ± 0.2 at 3.0 T (Table 1). The relaxivity per CM-101 molecule was three times higher. CM-101 displayed low micromolar binding affinity to human and nonhuman type I collagen with Kd = 3.6, 4.4, and 7.4 μM to human, dog, and rat collagen, respectively. Owing to the repetitive structure of collagen, a (Gly-Pro-X)n triple helix, this compound binds to roughly 8–10 sites per collagen molecule, further amplifying MR signal sensitivity at the target.

Table 1.

Longitudinal (r1) and Transverse (r2) Relaxivities of CM-101, Expressed on a Per-Gadolinium Basis, in Phosphate-buffered Saline Measured at 37°C and 1.5 and 3.0 T

Characterization of CM-101 Biodistribution and Pharmacokinetics

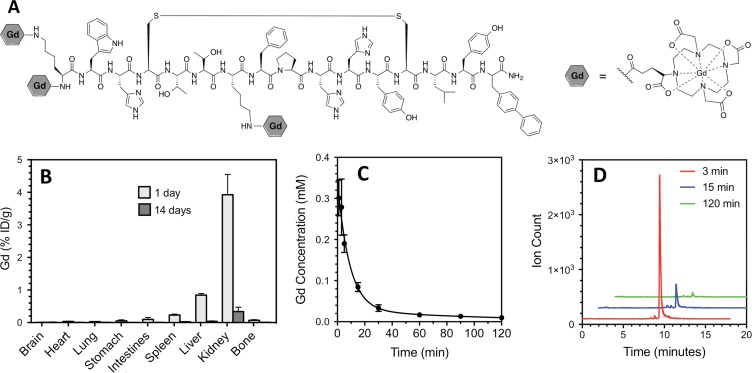

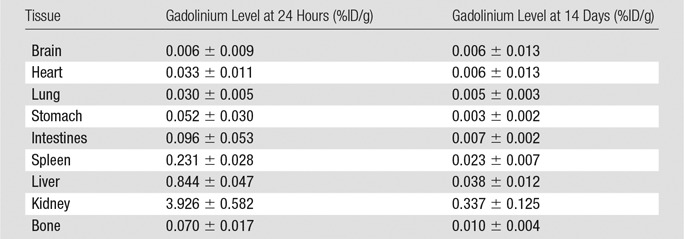

Analysis of ex vivo tissue from rats injected with CM-101 demonstrated predominately renal elimination, with 99.2% of the gadolinium recovered found in the urine and 0.8% found in the feces after a 24-hour collection period. Very low levels of gadolinium remained at 24 hours, and these levels dropped about 10-fold lower at 14 days after CM-101 injection (Fig 1, B). The tissue with the highest concentration of gadolinium was kidney, with 3.9% ± 0.6 of the injected dose (ID) per gram of kidney tissue at 24 hours and 0.33% ID/g ± 0.12 at 14 days. Negligible gadolinium accumulation was observed in bone (Fig 1, B) with 0.07% ID/g ± 0.02 observed at 24 hours and 0.010% ID/g ± 0.004 observed at 14 days. The quantitative gadolinium levels at 24 hours and 14 days after CM-101 injection for all tissues are given in Table 2. The gadolinium blood plasma clearance (Fig 1, C) was fit to an exponential decay with a half-life of 6.8 minutes ± 2.4. High-performance liquid chromatography/inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry chromatograms of blood plasma sampled after CM-101 injection showed the presence of intact CM-101 and some minor metabolites, likely peptide fragments (Fig 1, D). CM-101 represented 97% of circulating gadolinium in plasma at 3 minutes after injection, 77% at 15 minutes, and about 50% from 60 to 120 minutes.

Figure 1:

CM-101 structure, biodistribution, and blood plasma clearance and stability. A, Structure of CM-101 containing three Gd-DOTA chelates. B, Gadolinium biodistribution in tissues 1 day and 14 days after injection of 10 µmol/kg CM-101 showed low levels of gadolinium remaining at 24 hours (n = 7) and 10-fold lower levels at 14 days (n = 8) after CM-101 injection, with negligible accumulation in bone. C, Gadolinium concentration in blood plasma measured as a function of time after CM-101 injection (n = 4 per time point). The blood clearance of CM-101 was fit to an exponential decay with half-life = 6.8 minutes ± 2.4. The biodistribution and plasma clearance data are consistent with rapid renal clearance of the probe. D, High-performance liquid chromatography/inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry of mouse blood plasma sampled 3 (red trace), 15 (blue trace), and 120 (green trace) minutes after CM-101 injection shows that the dominant gadolinium species in plasma is CM-101 and that its plasma elimination is very fast.

Table 2.

Tissue Gadolinium Levels Measured in Rats 24 Hours (n = 7) and 14 Days (n = 8) after Injection of CM-101

Characterization of Liver Fibrosis in Animal Models

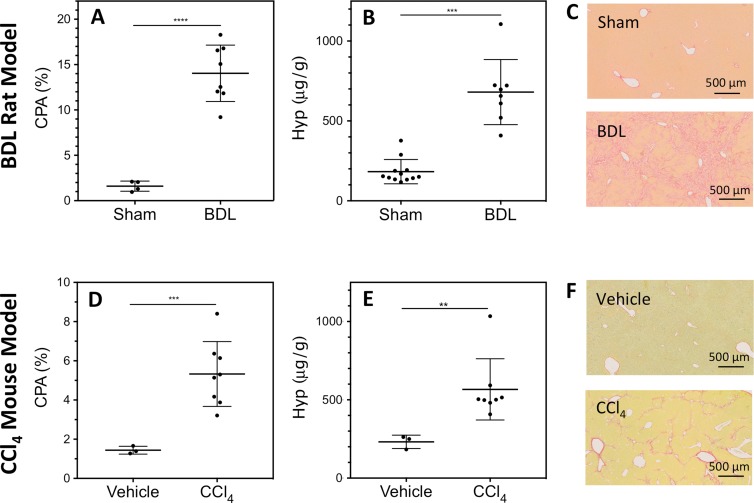

For the BDL rat model of liver fibrosis, the liver CPA was significantly greater (P < .0001) in BDL rats (14.0% ± 1.6) than in sham-treated rats (1.6% ± 0.6) (Fig 2, A). BDL rat livers also had significantly (P = .001) elevated hydroxyproline content (680 μg/g ± 204) than sham-treated animals (182 μg/g ± 76) (Fig 2, B). In addition, all sham-treated rats (n = 11) had an Ishak score of 0 (100%), while the BDL rats (n = 8) had an Ishak score of either 5 (12.5%) or 6 (87.5%). The Ishak scores were significantly different (P < .0001) for BDL and sham-treated rats. Representative Sirius Red–stained liver sections for BDL and sham-treated animals are shown in Figure 2, C.

Figure 2:

Characterization of rodent liver fibrosis models. Dot plots of, A, D, liver CPA, B, E, hydroxyproline (Hyp) concentration, and, C, F, representative Sirius Red–stained histologic images for (top row) BDL rat and (bottom row) CCl4-treated mouse models of liver fibrosis. Central dark band = mean, whiskers = standard deviation. Significant differences in CPA and hydroxyproline were observed between sham-treated (n = 11) and BDL (n = 8) rats and between vehicle-treated (n = 3) and CCl4-treated (n = 8) mice.

Similarly, the CCl4 mouse model of liver fibrosis demonstrated significantly (P = .0002) greater CPA in CCl4-treated mice (5.3% ± 1.7) than in vehicle-treated mice (1.4% ± 0.2). Liver hydroxyproline content was also significantly (P = .0016) elevated in CCl4-treated mice (567 μg/g ± 232) compared with vehicle-treated mice (231 μg/g ± 43) mice (Fig 2, E). In addition, all CCl4 mice (n = 8) had an Ishak score of 5 (100%), while vehicle-treated mice (n = 3) had Ishak scores of either 0 (66.6%) or 1 (33.3%). The Ishak scores were significantly different (P = .0083) for CCl4- and vehicle-treated mice. Representative Sirius Red–stained liver sections for CCl4- and vehicle-treated animals are shown in Figure 2, F.

Molecular MR Imaging of Liver Fibrosis

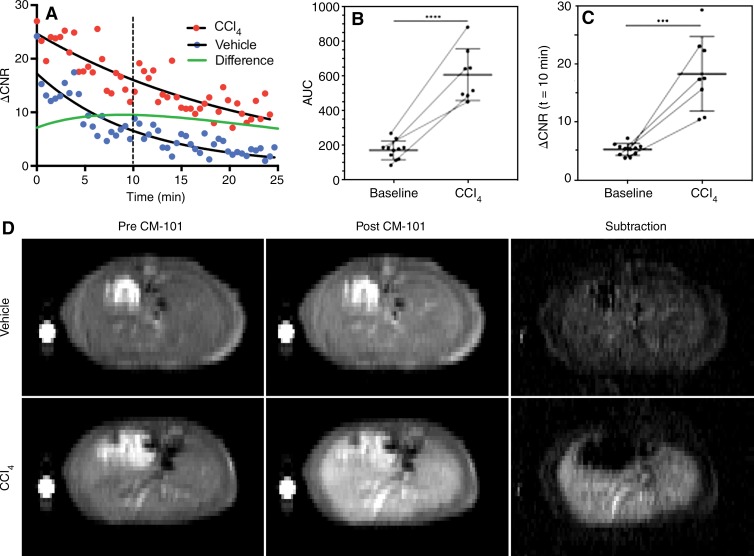

The CNR between liver and muscle was monitored dynamically after injection of CM-101 in the rat and mouse liver fibrosis models. Both the AUC and the ΔCNR at a fixed time point were used to assess liver fibrosis. Shown in Figure 3, A are ΔCNR curves for representative vehicle- and CCl4-treated mice. Exponential curves were fit to the ΔCNR decays after CM-101 injection, and the maximal difference between the fitted curves for CCl4- and vehicle-treated animals was observed approximately 10 minutes after CM-101 injection. The average AUC for CCl4 mice (601 ± 150, n = 8) was significantly (P < .0001) greater than the average for all baseline (163 ± 54, n = 11) mice (Fig 3, B). Similarly, the average ΔCNR at 10 minutes after CM-101 injection was significantly (P < .001) greater for CCl4 (18.3 ± 6.5, n = 8) compared with baseline (5.2 ± 1.0, n = 11) mice (Fig 3c).

Figure 3:

Change in CNR after CM-101 injection in mouse CCl4 model. A, Representative dynamic time courses of the ΔCNR between liver and muscle tissue for CCl4-treated (red dots) and vehicle-treated (blue dots) mice after injection of CM-101. The maximal difference in ΔCNR (green line) between CCl4-treated and vehicle-treated mice was observed at approximately 10 minutes after CM-101 injection. B, A significant (P < .0001) difference in the AUC between baseline (n = 11) and CCl4-treated (n = 8) mice was observed. Paired mice at the two time points (n = 4) are indicated by a thin line connecting the data points. C, A significant (P < .001) difference in ΔCNR between baseline and CCl4-treated mice was also observed at 10 minutes after CM-101 injection. Paired mice at the two time points (n = 4) are indicated by a thin line connecting the data points. D, Representative T1-weighted RARE images acquired before CM-101 injection, 10 minutes after CM-101 injection, and the associated subtraction images for vehicle- and CCl4-treated animals.

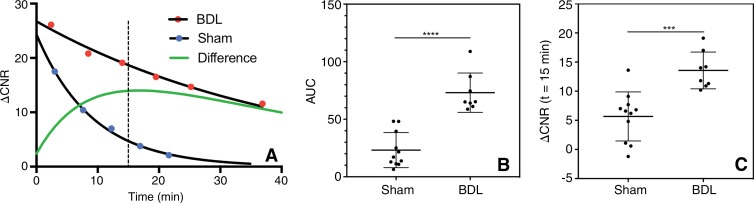

Representative ΔCNR curves for BDL and sham-treated rats are shown in Figure 4, A. CM-101 cleared much more slowly in BDL rats than in sham-treated rats, with a maximal difference in ΔCNR between BDL and sham-treated rats observed at 15 minutes after CM-101 injection. The average AUC for BDL rats (73.1 ± 17.1, n = 8) was significantly (P < .0001) greater than that for sham-treated rats (23.2 ± 15.2, n = 11) rats (Fig 4, B). Similarly, the average ΔCNR at 15 minutes after CM-101 injection was significantly (P < .001) greater for BDL rats (13.6 ± 3.2, n = 8) than for sham-treated rats (5.7 ± 4.2, n = 11) (Fig 4, C). BDL rats also displayed a significantly (P = .0026) greater change in R1 relaxation rate (ΔR1) 30 minutes after CM-101 injection (ΔR1 = 0.50 ± 0.23 sec−1, n = 8) compared with sham rats (ΔR1 = 0.15 ± 0.14 sec−1, n = 11) (see Fig E1 [online]).

Figure 4:

Change in CNR after CM-101 injection in a rat BDL model. A, Representative dynamic time courses of ΔCNR between liver and muscle tissue for BDL (red dots) and sham-treated (blue dots) rats after injection of CM-101. The maximal difference in ΔCNR (green line) between sham-treated and BDL rats was observed at approximately 15 minutes after CM-101 injection. B, A significant (P < .0001) difference in the AUC between sham-treated (n = 11) and BDL (n = 8) rats was observed. C, A significant (P < .001) difference in ΔCNR between sham-treated and BDL rats was also observed at 15 minutes after CM-101 injection.

Correlation of MR Imaging and Histologic Biomarkers

For the mouse CCl4 model of liver fibrosis, the AUCs correlated significantly with ex vivo quantification of both liver CPA (Fig E2, A [online]; P = .0008, R = 0.86) and hydroxyproline content (Fig E2, C [online]; P = .0154, R = 0.70). Similarly, for the rat model of liver fibrosis, the AUCs correlated significantly with ex vivo quantification of both liver CPA (Fig E2, B [online]; P < .0001, R = 0.84) and hydroxyproline content (Fig E2, D [online]; P = .0001, R = 0.77).

For the mouse CCl4 model of liver fibrosis, the ΔCNR 10 minutes after CM-101 injection also correlated significantly with ex vivo quantification of both liver CPA (Fig E3, A [online]; P = .0018, R = 0.83) and hydroxyproline content (Fig E3, C [online]; P = .0030, R = 0.80). Similarly, for the rat model of liver fibrosis, the ΔCNR 15 minutes after CM-101 injection correlated significantly with ex vivo quantification of both liver CPA (Fig E3, B [online]; P = .0002, R = 0.75) and hydroxyproline content (Fig E3, D [online]; P = .0009, R = 0.70).

Discussion

While the type I collagen–targeted MR contrast agent EP-3533 has previously been shown to help stage liver fibrosis and assess response to antifibrotic therapies with high sensitivity and specificity in several rodent models (13–17), its clinical translation is precluded because of the low stability of the linear Gd-DTPA chelator used. Gd-DTPA (gadopentetate dimeglumine) has been associated with nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in patients with renal impairment, leading to a contraindication in this patient group. For a targeted agent like EP-3533, one may expect a longer exposure than for Gd-DTPA and a greater risk of gadolinium release. Indeed, EP-3533 was shown to accumulate in the kidneys and bone of mice 24 hours after injection (13,15). Peptide-based imaging probes often show some transient kidney retention (22), but bone uptake is associated with “free” unchelated gadolinium (23). We hypothesized that replacing the linear DTPA chelator with the macrocyclic, ionic DOTA chelator would mitigate gadolinium release and bone accumulation of gadolinium. In all measures of kinetic inertness—that is, the rate at which gadolinium is released from the chelator, Gd-DOTA has been shown to be far superior to the linear chelators and to the other macrocyclic chelators used clinically (24). We also reasoned that with a stable Gd-DOTA chelate, the gadolinium in the kidney would clear with time. This was the behavior observed with CM-101. There was very low bone uptake (30-fold lower than that observed with EP-3533 [15]), and the small amounts of gadolinium measured in the kidneys, liver, and spleen at 1 day after injection were reduced by an order of magnitude at day 14.

Similar to EP-3533, CM-101 was able to depict fibrosis in two different rodent models of liver fibrosis: a BDL rat and a CCl4 mouse model of liver fibrosis. Significant differences (P < .01) between control and fibrotic animals were observed for all MR imaging metrics examined, including AUC, ΔCNR at a fixed time point, and ΔR1. We calculated the difference between the time-dependent ΔCNR data in diseased and control animals, and, by using the maximum in this difference curve, we were able to identify an optimal time for imaging after probe injection. This optimal time was 10 minutes after injection in mice and 15 minutes after injection in rats. These optimal imaging times are much shorter than what was used with EP-3533, where a delay of 40–45 minutes was used (14–17). The ability to image liver fibrosis at an early time after injection can be attributed to the more rapid elimination of CM-101 from the blood (blood half-life = 6.8 minutes ± 2.4) compared with EP-3533 (blood half-life = 19 minutes ± 2 in mice [15]), which results in a lower background signal with CM-101.

An additional improvement in CM-101 compared with EP-3533 is the reduced blood half-life. The Gd-DTPA chelates in EP-3533 are conjugated by a benzyl thiourea linkage, while the Gd-DOTA groups in CM-101 are conjugated by a short three-carbon-amide linkage. The increased lipophilicity imparted by the three benzyl groups in EP-3533 may result in increased plasma protein binding and an extended blood half-life. The rapid elimination time of CM-101 is beneficial for clinical translation because the postcontrast images can be acquired in a short time (15 minutes) after probe injection. This time period is compatible with a single examination for liver fibrosis where baseline and postcontrast images are acquired in the same study. A challenge with molecular MR imaging in general has been the need to wait a long time for target localization and/or blood clearance, necessitating separate pre- and postcontrast agent imaging sessions. Two imaging sessions bring challenges in patient compliance, difficulties in image coregistration, and imaging unit drift. The fast elimination time of CM-101 and the ability to image liver fibrosis early after injection circumvents these problems.

The ability of CM-101 to depict fibrosis was assessed at two independent sites. At one site, a rat study was performed with a BDL model of obstructive cholestatic injury causing biliary fibrosis originating from the periportal region. Images were acquired with a 1.5-T clinical MR imaging unit by using an inversion-recovery FLASH imaging sequence. At the other site, a mouse study was performed with a CCl4 model of centrilobular liver necrosis causing liver fibrosis. Here the images were acquired with a 7.0-T preclinical imaging unit by using a RARE imaging sequence. Two different MR imaging physicists performed the two studies. For both the imaging and the ex vivo analyses (hydroxyproline, Ishak scoring, and CPA analysis), the inverstigators were blinded as to whether the animals had disease. In both studies, robust and significant differences in AUC and ΔCNR between control and fibrotic animals were observed that were significantly correlated with CPA and hydroxyproline histologic measures of fibrosis. This suggests that the detection of fibrosis with CM-101 is robust against differences in MR imaging units, operators, imaging protocols, and fibrosis source.

A limitation of the current study was that it did not directly assess specificity by including a negative control probe. In previous studies with the related EP-3533 probe, it was demonstrated that the collagen-binding peptide was necessary for detection and staging of fibrosis (20,25). In those studies, a nonbinding isomer of EP-3533 that had the same relaxivity and pharmacokinetics was used as a negative control, and this demonstrated the in vivo specificity of EP-3533 for fibrosis. Similarly, comparison of EP-3533 with Gd-DTPA indicated that only the former could be used to detect liver fibrosis in mouse and rat models (14). Because CM-101 and EP-3533 differ only in chelate type but share the same collagen-binding peptide, studies with a negative control probe were not repeated here.

In summary, CM-101 is a collagen-targeted, peptide-based probe using highly stable Gd-DOTA chelates that is rapidly eliminated from plasma intact into urine, shows minimal gadolinium accumulation in bone, and robustly depicted liver fibrosis in BDL rat and CCl4 mouse models. These characteristics all make CM-101 potentially suitable for clinical translation.

Advances in Knowledge

■ CM-101, a type I collagen–targeted contrast agent, was able to depict liver fibrosis in both a bile duct–ligated (BDL) rat model and a carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) mouse model.

■ Significantly (P < .001) greater changes in contrast-to-noise ratio (ΔCNRs) between liver and muscle tissue after CM-101 injection were observed for BDL rats (13.6 ± 3.2) compared with sham-treated rats (5.7 ± 4.2) and for CCl4 mice (18.3 ± 6.5) compared with baseline mice (5.2 ± 1.0).

■ CM-101 uses the very stable gadoterate meglumine chelate and showed negligible accumulation of gadolinium in tissues, with less than 0.33% of injected dose (ID) per gram of tissue and 0.01% of ID per gram of bone remaining at 14 days after administration to rats.

■ CM-101 demonstrated rapid blood plasma clearance (half-life = 6.8 minutes ± 2.4) and predominately renal elimination in rats.

Implications for Patient Care

■ Molecular MR imaging with the collagen-targeted probe CM-101 provided robust detection of liver fibrosis in two animal models and may enable noninvasive detection and staging of liver fibrosis and monitoring of treatment response in patients with fibrotic liver disease.

■ The high chemical stability, fast blood clearance, and whole-body elimination of CM-101 coupled with robust fibrosis imaging suggest that CM-101 may be a suitable candidate for clinical translation.

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURES

Received March 14, 2017; revision requested May 5; revision received June 4; accepted June 26; final version accepted September 14.

Study supported by the National Institutes of Health (P41-RR14075, R01-DK104956, R44-DK095617, S10-OD010650, S10-RR023385).

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: C.T.F. disclosed no relevant relationships. E.M.G. Activities related to the present article: has received fees for consulting and contract work from Collagen Medical. Activities not related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. R.K. disclosed no relevant relationships. I.R. disclosed no relevant relationships. R.M. disclosed no relevant relationships. G.A. disclosed no relevant relationships. K.L. disclosed no relevant relationships. L.W. disclosed no relevant relationships. J.K. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: has received personal fees from INFOTECH Soft. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. M.M.B. disclosed no relevant relationships. C.Z. disclosed no relevant relationships. Y.Z. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: holds stock or stock options in Merck. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. T.E.A. Activities related to the present article: is an employee of Merck. Activities not related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. M.K. Activities related to the present article: is an employee of Merck. Activities not related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. S.P. disclosed no relevant relationships. H.D. disclosed no relevant relationships. K.K.T. disclosed no relevant relationships. V.H. disclosed no relevant relationships. B.C.F. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: was a paid consultant for Collagen Medical prior to this study; has a grant from Collagen Medical. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. P.C. Activities related to the present article: is a consultant for and owns stock in Collagen Medical. Activities not related to the present article: has received fees or funding from Guerbet, Reveal Pharmaceuticals, Factor 1A, and Pfizer. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships.

Abbreviations:

- AUC

- area under the ΔCNR curve

- BLD

- bile duct ligated

- CNR

- contrast-to-noise ratio

- ΔCNR

- change in CNR

- CPA

- collagen proportional area

- FLASH

- fast low-angle shot

- Gd-DOTA

- gadoterate meglumine

- Gd-DTPA

- gadopentetate dimeglumine

- ID

- injected dose

- RARE

- rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement

References

- 1.Williams R. Global challenges in liver disease. Hepatology 2006;44(3):521–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miniño AM. Death in the United States, 2009. NCHS Data Brief 2011(64):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iredale JP. Models of liver fibrosis: exploring the dynamic nature of inflammation and repair in a solid organ. J Clin Invest 2007;117(3):539–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology 2008;134(6):1655–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuppan D, Afdhal NH. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet 2008;371(9615):838–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman SL. Evolving challenges in hepatic fibrosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;7(8):425–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman SL, Bansal MB. Reversal of hepatic fibrosis: fact or fantasy? Hepatology 2006;43(2 Suppl 1):S82–S88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fallowfield JA, Kendall TJ, Iredale JP. Reversal of fibrosis: no longer a pipe dream? Clin Liver Dis 2006;10(3):481–497, viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myers RP, Fong A, Shaheen AA. Utilization rates, complications and costs of percutaneous liver biopsy: a population-based study including 4275 biopsies. Liver Int 2008;28(5):705–712 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terjung B, Lemnitzer I, Dumoulin FL, et al. Bleeding complications after percutaneous liver biopsy: an analysis of risk factors. Digestion 2003;67(3):138–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Popov Y, Schuppan D. Targeting liver fibrosis: strategies for development and validation of antifibrotic therapies. Hepatology 2009;50(4):1294–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motola DL, Caravan P, Chung RT, Fuchs BC. Noninvasive biomarkers of liver fibrosis: clinical applications and future directions. Curr Pathobiol Rep 2014;2(4):245–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caravan P, Das B, Dumas S, et al. Collagen-targeted MRI contrast agent for molecular imaging of fibrosis. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2007;46(43):8171–8173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polasek M, Fuchs BC, Uppal R, et al. Molecular MR imaging of liver fibrosis: a feasibility study using rat and mouse models. J Hepatol 2012;57(3):549–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuchs BC, Wang H, Yang Y, et al. Molecular MRI of collagen to diagnose and stage liver fibrosis. J Hepatol 2013;59(5):992–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farrar CT, DePeralta DK, Day H, et al. 3D molecular MR imaging of liver fibrosis and response to rapamycin therapy in a bile duct ligation rat model. J Hepatol 2015;63(3):689–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu B, Rotile N, Day H, et al. Combined magnetic resonance elastography and collagen molecular magnetic resonance imaging accurately stage liver fibrosis in a rat model. Hepatology 2017;65(3):1015–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marckmann P, Skov L, Rossen K, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: suspected causative role of gadodiamide used for contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006;17(9):2359–2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol 1995;22(6):696–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caravan P, Yang Y, Zachariah R, et al. Molecular magnetic resonance imaging of pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2013;49(6):1120–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hutson PR, Crawford ME, Sorkness RL. Liquid chromatographic determination of hydroxyproline in tissue samples. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2003;791(1-2):427–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laverman P, Joosten L, Eek A, et al. Comparative biodistribution of 12 111In-labelled gastrin/CCK2 receptor-targeting peptides. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2011;38(8):1410–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tweedle MF, Wedeking P, Kumar K. Biodistribution of radiolabeled, formulated gadopentetate, gadoteridol, gadoterate, and gadodiamide in mice and rats. Invest Radiol 1995;30(6):372–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Port M, Idée JM, Medina C, Robic C, Sabatou M, Corot C. Efficiency, thermodynamic and kinetic stability of marketed gadolinium chelates and their possible clinical consequences: a critical review. Biometals 2008;21(4):469–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helm PA, Caravan P, French BA, et al. Postinfarction myocardial scarring in mice: molecular MR imaging with use of a collagen-targeting contrast agent. Radiology 2008;247(3):788–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.