Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to examine the association between homologous recombination repair (HRR)-related gene mutations and efficacy of oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC).

Results

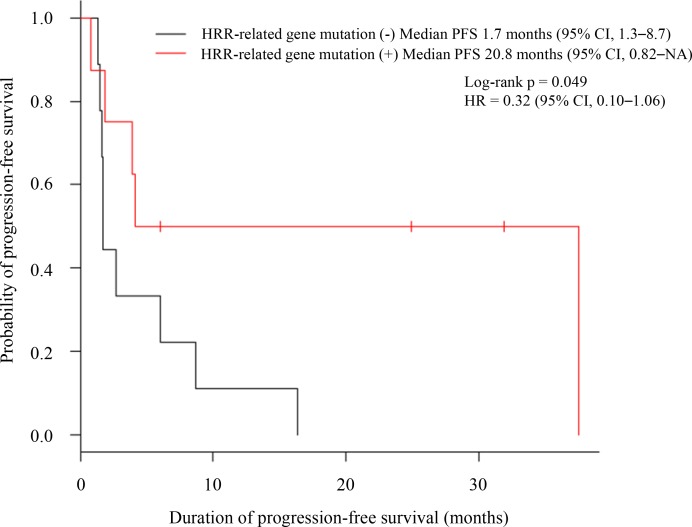

Non-synonymous mutations in HRR-related genes were found in 13 patients and only one patient had a family history of pancreatic cancer. Eight patients with HRR-related gene mutations (group A) and nine without HRR-related gene mutations (group B) received oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy. Median progression-free survival after initiation of oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy was significantly longer in group A than in group B (20.8 months vs 1.7 months, p = 0.049). Interestingly, two patients with inactivating HRR-related gene mutations who received FOLFIRINOX as first-line treatment showed exceptional responses with respect to progression-free survival for > 24 months.

Materials and Methods

Complete coding exons of 12 HRR-related genes (ATM, ATR, BAP1, BRCA1, BRCA2, BLM, CHEK1, CHEK2, FANCA, MRE11A, PALB2, and RAD51) were sequenced using a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment-certified multiplex next-generation sequencing assay. Thirty consecutive PDAC patients who underwent this assay between April 2015 and July 2017 were included.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that inactivating HRR-related gene mutations are predictive of response to oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with PDAC.

Keywords: BRCA, homologous recombination repair, oxaliplatin, pancreatic cancer, precision medicine

INTRODUCTION

BRCA1 and BRCA2 play pivotal roles in DNA homologous recombination repair (HRR), and germline BRCA1/2 mutations reportedly increase risk of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). A large clinic-based cohort study enrolling 306 patients with PDAC reported the prevalence of pathogenic BRCA1/2 germline mutations to be 4.6% [1]. Moreover, several retrospective studies have indicated that patients with PDAC harboring germline BRCA1/2 mutations are more sensitive to platinum-based chemotherapy than those without the mutations [2–4].

In addition to BRCA1/2, other genes such as ATM, ATR, and PALB2 are involved in HRR [5]. In ovarian cancer, both germline and somatic mutations in HRR-related genes are predictive of response to platinum-based chemotherapy [6]. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that patients with PDAC harboring mutations in HRR-related genes in their tumor tissues are sensitive to platinum-based chemotherapy. Supporting this idea, Waddell et al. reported that four of five patients with PDAC who were deficient in BRCA1/2 or PALB2 responded to platinum-based chemotherapy [7].

Oxaliplatin, a third-generation diaminocyclohexane platinum compound, is now commonly used in patients with PDAC [8–12]. However, to date, studies in patients with PDAC investigating prevalence of HRR-related gene mutations in tumor tissues and their association with efficacy of oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy are sparse. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the association between HRR-related gene mutations identified using a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment (CLIA)-certified multiplex next-generation sequencing (NGS) assay (OncoPrimeTM) [13] and efficacy of oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with PDAC.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1, and characteristics of individual patients are shown in Table 2. The median age was 64 (range 39–81) years.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

| Number of Patients (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRR-related gene mutation | Total | |||

| (+) n = 13 |

(−) n = 15 |

|||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 7 | 8 | 15 (53.6) | |

| Female | 6 | 7 | 13 (46.4) | |

| Age, years | ||||

| Median | 61 | 64 | 64 | |

| Range | 44–81 | 39–74 | 39–81 | |

| Age ≤ 60 years | 6 | 6 | 12 (42.9) | |

| Disease status | ||||

| Locally advanced | 5 | 2 | 7 (25.0) | |

| Metastatic | 5 | 6 | 11 (39.3) | |

| Recurrence | 3 | 7 | 10 (35.7) | |

| Family history of cancer | ||||

| Yes | 8 | 9 | 17 (60.7) | |

| No | 3 | 4 | 7 (25.0) | |

| Unknown | 2 | 2 | 4 (14.3) | |

| Family history of pancreatic caner | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 3 | 4 (14.3) | |

| No | 10 | 10 | 20 (71.4) | |

| Unknown | 2 | 2 | 4 (14.3) | |

| Oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy | ||||

| Yes | 8 | 9 | 17 (60.7) | |

| No | 5 | 6 | 11 (39.3) | |

Table 2. Characteristics of individual patients.

| Case | Age | Sex | Family history of cancer | Disease status | Oxaliplatin-based regimen | Identification of HRR-related gene mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 66 | F | Unknown | Metastatic | FOLFIRINOX | No |

| 2 | 52 | F | Gastric cancer (FDR), Colorectal cancer (TDR), Lung cancer (TDR) | Metastatic | FOLFIRINOX | No |

| 3 | 42 | M | Pancreatic cancer (SDR) | Locally advanced | SOX | No |

| 4 | 64 | M | None | Locally advanced | GEMOX | No |

| 5 | 39 | F | Cutaneous cancer (FDR) Esophageal cancer (TRD) |

Metastatic | SOX | No |

| 6 | 64 | M | None | Recurrence after adjuvant S-1 | SOX | No |

| 7 | 74 | F | Lung cancer (FDR) | Recurrence after adjuvant S-1 | SOX | No |

| 8 | 65 | M | Gastric cancer (FDR), Lung cancer (TDR) | Metastatic | SOX | No |

| 9 | 66 | F | Unknown | Recurrence after adjuvant S-1 | GEMOX | No |

| 10 | 55 | M | None | Metastatic | FOLFIRINOX | Yes |

| 11 | 52 | M | Brain tumor (FDR) Prostate cancer (TRD) |

Locally advanced | FOLFIRINOX | Yes |

| 12 | 68 | M | Gastric cancer (FDR) | Metastatic | FOLFIRINOX | Yes |

| 13 | 47 | M | Pancreatic cancer (FDR) | Metastatic | GEMOX | Yes |

| 14 | 44 | M | None | Recurrence after adjuvant S-1 | SOX | Yes |

| 15 | 65 | F | Gastric cancer, Colorectal cancer (FDR) | Metastatic | FOLFOX | Yes |

| 16 | 81 | M | Unknown cancer (FDR) | Metastatic | SOX | Yes |

| 17 | 57 | F | Gastric cancer (FDR) | Recurrence | SOX | Yes |

| 18 | 65 | M | Biliary tract cancer (FDR) | Recurrence | - | No |

| 19 | 45 | M | None | Metastatic | - | No |

| 20 | 73 | M | Colorectal cancer (FDR) | Recurrence after adjuvant S-1 | - | No |

| 21 | 60 | F | Pancreatic cancer (FDR) | Recurrence after adjuvant S-1 | - | No |

| 22 | 59 | F | Gastric cancer (SDR) Pancreatic cancer (TDR) |

Recurrence after adjuvant S-1 | - | No |

| 23 | 67 | M | None | Recurrence | - | No |

| 24 | 60 | F | Unknown | Recurrence after adjuvant S-1 | - | Yes |

| 25 | 61 | M | Breast cancer (FDR) | Locally advanced | - | Yes |

| 26 | 67 | F | Gastric cancer (FDR) | Locally advanced | - | Yes |

| 27 | 77 | F | Unknown | Locally advanced | - | Yes |

| 28 | 74 | F | None | Locally advanced | - | Yes |

FDR, first-degree relative; SDR, second-degree relative; TDR, third-degree relative.

Completion rate of the NGS-based multiplex gene assay

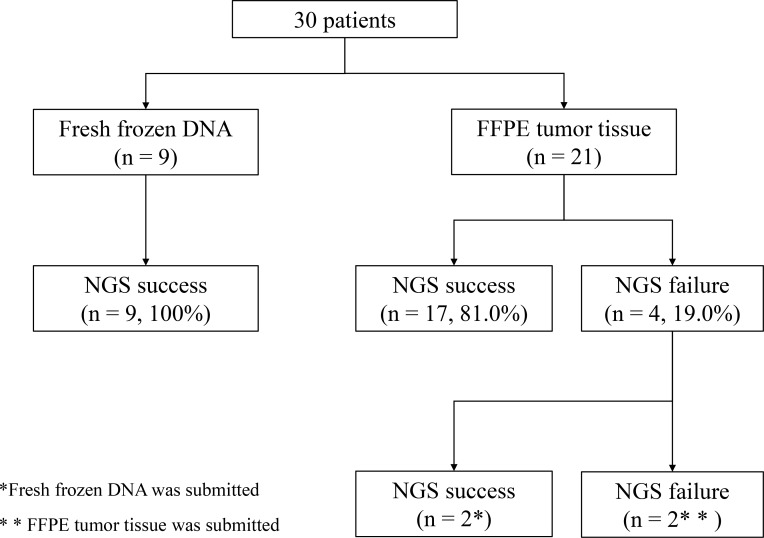

The NGS-based multiplex gene assay was performed using archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissues (n = 21) or fresh frozen tumor tissues obtained from liver metastases (n = 5), primary sites (n = 3), and a lymph node metastasis (n = 1). The first NGS assay failed in four patients because of poor DNA quality, and a second assay was successfully completed in two patients using fresh frozen tissue obtained via fine-needle aspiration from a liver metastasis (n = 1) and a primary site (n = 1). The overall completion rate of the NGS assay was 93.3% (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Success rate of multiplex next-generation sequencing (NGS) assay in 30 consecutive patients with pancreatic cancer.

Identification of non-synonymous mutations in HRR-related genes

The identified HRR-related gene mutations and their corresponding ID, reported in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) database and the reference single nucleotide polymorphism (rs) ID in dbSNP, are summarized in Table 3. BRCA2 was the most commonly mutated gene (n = 10), followed by ATM (n = 8), BRCA1 (n = 2), CHEK2 (n = 2), ATR (n = 1), and PALB2 (n = 1). In total, non-synonymous HRR-related gene mutations were identified in 13 patients (46.4%). Germline allele frequency of each variant in the normal population as reported in the Exome Aggregation Consortium (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/) and Human Genetic Variation Database (http://www.hgvd.genome.med.kyoto-u.ac.jp/) are also summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Identified HRR-related gene mutations.

| Case | Gene | Mutation | Function | COSMIC ID | dbSNP ID | Germline test | ExAC | ExAc East Asian |

HGVD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | ATR | I774fs | Inactivating mutation | 1617015 | Not reported | negative | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| ATM | L2005V | VUS | Not reported | Not reported | positive | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |

| BRCA2 | I1929V | VUS | Not reported | rs79538375 | positive | 9.6e-04 | 9.8e-03 | Not reported | |

| 11 | ATM | R2034X | Inactivating mutation | 922732 | rs532480170 | - | 1.7e-05 | 0 | Not reported |

| ATM | L2426I | VUS | Not reported | Not reported | - | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |

| BRCA1 | L52F | VUS | Not reported | rs80357084 | - | 1.3e-04 | 1.8e-03 | 2.5e-03 | |

| 12 | BRCA2 | S1989fs | Inactivating mutation | Not reported | rs80359552 | - | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| BRCA2 | N2436I | VUS | Not reported | rs80358955 | - | 8.2e-06 | 0 | 2.1e-03 | |

| CHEK2 | R474C | Inactivating mutation | Not reported | rs540635787 | - | 8.8e-06 | 1.2e-04 | Not reported | |

| 13 | ATM | R1618X | Inactivating mutation | 1350875 | Not reported | positive | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| 14 | BRCA2 | Q3026X | Inactivating mutation | 3468418 | rs80359159 | - | 1.7e-05 | 0 | Not reported |

| 15 | ATM | L1700fs | Inactivating mutation | Not reported | Not reported | - | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| 16 | PALB2 | splice site 3350+5G>A | VUS | Not reported | rs587782566 | positive | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| BRCA2 | A2351G | VUS | Not reported | rs80358932 | positive | 1.3e-04 | 1.7e-03 | 1.2e-03 | |

| 17 | BRCA1 | R1443X | Inactivating mutation | 979730 | rs41293455 | - | 1.6e-05 | 0 | Not reported |

| 24 | BRCA2 | S871X | Inactivating mutation | Not reported | rs397507634 | negative | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| BRCA2 | splice site 7977-2A>T | Inactivating mutation | Not reported | rs276174899 | negative | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |

| BRCA2 | V2503I | VUS | Not reported | rs587782191 | negative | 8.2e-06 | Not reported | 4.2e-04 | |

| ATM | R2691C | VUS | 922745 | rs531980488 | negative | 1.1e-04 | 7.0e-04 | Not reported | |

| 25 | ATM | V1038X | Inactivating mutation | Not reported | Not reported | - | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| 26 | BRCA2 | R2318X | Inactivating mutation | Not reported | rs80358920 | - | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| 27 | BRCA2 | I1929V | VUS | Not reported | rs79538375 | - | 9.6e-04 | 9.8e-03 | 0.012 |

| ATM | V2951I | VUS | Not reported | Not reported | - | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |

| 28 | CHEK2 | splice site 1591-1G>A | VUS | Not reported | Not reported | - | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

VUS, variant of unknown significance; ExAC, Exome Aggregation Consortium; HGVD, Human Genetic Variation Database.

Family history of cancer

Among the 28 patients evaluated, family history of any cancer and of pancreatic cancer within third-degree relatives was confirmed in 17 (60.7%) and four patients (14.3%), respectively. Of the 13 patients harboring HRR-related gene mutations, only one had a family history of pancreatic cancer (Table 1).

Efficacy of oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy

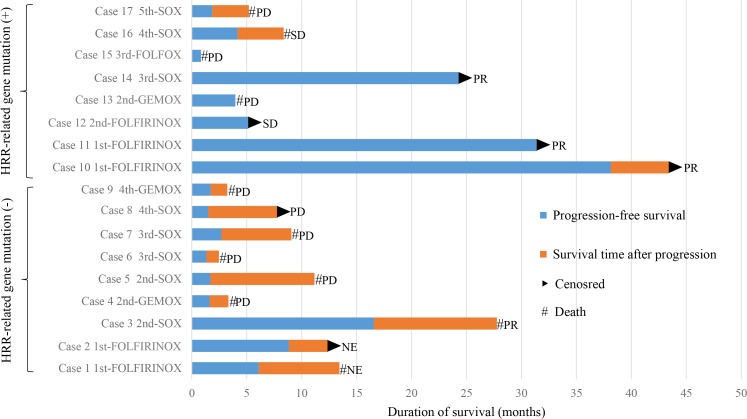

Of the 28 patients evaluated, 17 received oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy. Treatment regimens are summarized in Table 2. Three radiologic responses and one tumor marker response (CA 19-9 and CEA decrease > 60%) were observed in patients harboring HRR-related gene mutations while only one radiologic response was observed in those without such mutations. Progression-free survival (PFS) and survival time after progression in individual patients are shown in Figure 2. Median PFS was significantly longer in patients with HRR-related gene mutations than those without mutations (20.8 months vs. 1.7 months, respectively; p = 0.049, Figure 3) and hazard ratio (HR) was 0.32 (95% confidence interval (CI), 0.10–1.06, p = 0.061).

Figure 2. Progression-free survival, survival time after progression, and the response of individual patients who received oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy.

Figure 3. Kaplan–Meier estimates of progression-free survival in patients who received oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy.

DISCUSSION

In this study, non-synonymous HRR-related gene mutations were identified in 13 (46.4%) of 28 consecutive patients with PDAC who were evaluated using an NGS-based multiplex gene assay covering complete coding exons of 12 HRR-related genes. Among the 13 patients with HRR-related gene mutations, only one (7.6%) had a family history of pancreatic cancer (Table 2). In line with our current results, Shindo et al. recently reported that among 27 patients with pancreatic cancer harboring pathogenic germline mutations in BRCA1/BRCA2/ATM/PALB2, only three patients (11.1%) had a family history of pancreatic cancer [14]. These data suggest that prevalence of HRR-related gene mutations is not uncommon, even if a patient has no family history of pancreatic cancer.

Efficacy of oxaliplatin-based chemotherapies such as FOLFIRINOX, FOLFOX, GEMOX, and SOX in pancreatic cancer has been tested in several clinical trials [8, 9, 11, 12]. Among these, only FOLFIRINOX exhibited clear significant benefit over gemcitabine monotherapy (control) in a large randomized clinical trial and has been recommended for a standard treatment regimen [8]. Conversely, SOX failed to exhibit benefit over S-1 monotherapy in a second-line setting in a randomized clinical trial and is not recommended as standard treatment in routine clinical practice [11]. However, in this study, we observed one patient with an inactivating HRR-related gene mutation (BRCA2 Q3026X) who did not respond to the standard chemotherapy of gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel but exhibited a partial response to SOX (Figure 2, Case 14). These results suggested that an oxaliplatin-based regimen, which failed to demonstrate a positive result in a clinical trial involving random patients with PDAC, is still beneficial in patients harboring HRR-related gene mutations.

Among 28 patients, 17 received oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy. In total, three of eight patients who harbored HRR-related gene mutations showed a radiologic response to oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy and one showed a CA19-9 and CEA decrease of > 60% at 8 weeks, which has been shown to be a predictor of better overall survival [15], whereas the response rate was 11.1% (1/9) among patients without such mutations. Interestingly, two patients with HRR-related gene mutations who received FOLFIRINOX as first-line treatment showed exceptional PFS responses for > 24 months (Figure 2, Cases 10 and 11). Because impaired HRR may confer sensitivity to platinum agents and topoisomerase inhibitors [5, 16, 17], patients with HRR-related gene mutations may experience greater benefit from FOLFIRINOX treatment.

On the other hand, four patients with HRR-related gene mutations showed neither radiologic nor tumor marker response to oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy. One patient (Case 13) refused to continue chemotherapy after the first cycle of GEMOX due to its toxicity. The other three patients (Case 15, 16, 17), received oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as third or later line treatment and this might have influenced the poor response. For example, Case 15 was obliged to discontinue chemotherapy after the first cycle of FOLFOX due to rapid deterioration of uncontrollable ascites. Therefore, to derive maximum benefit from oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with HRR-related gene mutations, it appears to be relevant to attempt this regimen at an earlier treatment time-point under better patient general status.

Pathogenic germline BRCA1/2 mutations are listed among the genes recommended for reporting of secondary findings by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) [18], and we follow this recommendation in daily clinical practice. In this study, suspected pathogenic germline BRCA1/2 mutations that met the ACMG recommendations were found in five patients (Table 3, Cases 12, 14, 17, 24, and 26). However, except for case 24, four patients did not undergo the germline test primarily because the test results would not affect their own cancer treatment. We were able to conduct the additional germline DNA test in four patients who provided informed consent, and five of 10 HRR-related mutations were confirmed to be germline mutations (Table 3).

Limitations of this study included a limited sample size, and differences in lines of treatment and oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy regimens among the patients. In addition, we could not eliminate the possibility that mutations identified in nine patients who did not undergo the germline test may have been derived from germline DNA.

In summary, the status of HRR-related gene mutations was positively associated with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with PDAC. Monitoring HRR-related genes using an NGS assay might be useful in selecting PDAC patients potentially sensitive to oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy. We are currently planning a prospective trial to verify the results reported here and further explore precision medicine in the field of pancreatic cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

A total of 30 consecutive patients with histologically confirmed PDAC who underwent an NGS-based multiplex assay (OncoPrimeTM) at Kyoto University Hospital between April 2015 and July 2017 were eligible for this study.

NGS-based multiplex assay (OncoPrimeTM)

An NGS-based multiplex assay (OncoPrimeTM) covers complete coding exons of 215 cancer-related genes and rearrangements in 17 frequently rearranged genes (Supplementary Table 1) [13, 19]. DNA extracted from archived FFPE tissue samples or fresh frozen tissue samples was used for this assay. NGS was performed in a CLIA-certified laboratory using Illumina HiSeq 2500 by EA Genomics (Morrisville, North Carolina, United States).

Identification of HRR-related gene mutations

Twelve HRR-related genes included in OncoPrimeTM (ATM, ATR, BAP1, BRCA1, BRCA2, BLM, CHEK1, CHEK2, FANCA, MRE11A, PALB2, and RAD51) were evaluated in this study. Variant calling was performed using variant calling software (VarPROWL) in a CLIA-certified laboratory by EA Genomics as previously reported [13] based on the following workflow:

Step 1: Remove all silent mutations in non-reference alleles, retaining mutations that are missense, are nonsense, or involve splicing junctions.

Step 2: Remove all non-reference alleles that appear in > 1% of the population (high minor allele frequency) because they are likely germline events.

Step 3: Remove all non-reference alleles with allele frequencies of < 4% and > 95%. This was performed because the limit of detection was 4% and alleles with > 95% frequency were most likely germline DNA because the sample material had at least 20% tumor content.

Step 4: The identified mutations were prioritized based on their presence in the following databases: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (https://www.omim.org/), ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/), Clinical Trials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/), Drug Bank (https://www.drugbank.ca/), COSMIC (http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic), and the Cancer Genome Atlas (https://cancergenome.nih.gov/).

After the filtering process mentioned above, non-synonymous mutations including variants of unknown significance were considered HRR-related gene mutations.

Efficacy of oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy

Oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy includes oxaliplatin, irinotecan, fluorouracil, and l-leucovorin (FOLFIRINOX); gemcitabine and oxaliplatin (GEMOX); and S-1 and oxaliplatin (SOX) [8, 11, 12]. Standard doses and schedules of the regimens were adjusted at the discretion of the treating physicians based on incidence of adverse events and individual patient general status. Clinical data were retrieved using a prospective cohort database system (CyberOncology®; Cyber Laboratory Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and electronic medical records.

Statistical analysis

Objective response was assessed based on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 [20]. PFS was defined as the interval between date of initiation of oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy and date of disease progression or death due to any cause. Survival time after disease progression was defined as the interval between date of disease progression and death. Patients not experiencing disease progression or death were censored at the last follow-up visit. Median PFS was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences were compared using the log-rank test. The hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval were calculated using Cox regression models. The data cutoff date was November 30, 2017. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.4.1.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine (G692) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent for the use of genomic and clinical data for research purposes.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS TABLE

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients, clinicians, and support staff who participated in this research.

Abbreviations

- CLIA

Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment

- COSMIC

catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer

- GEMOX

gemcitabine and oxaliplatin

- FOLFIRINOX

oxaliplatin, irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin

- FOLFOX

oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin

- HRR

homologous recombination repair

- NGS

next-generation sequencing

- OS

overall survival

- PD

progressive disease

- PDAC

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PFS

progression-free survival

- PR

partial response

- RECIST

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- SD

stable disease

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- SOX

S-1 and oxaliplatin

Footnotes

Author contributions

Tomohiro Kondo, Masashi Kanai: study concept and design; Tomohiro Kondo, Masashi Kanai, Tadayuki Kou, Shigemi Matsumoto, and Manabu Muto: acquisition of data; Norimitsu Uza, Yuzo Kodama, Toshihiko Masui, and Kyoichi Takaori: acquisition of sample for NGS; Tomohiro Sakuma, Hiroaki Mochizuki, Mayumi Kamada, Masahiko Nakatsui, Hidehiko Miyake, and Yasushi Okuno: NGS, including data analysis and interpretation; all authors participated in writing and approved the final submitted manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Masashi Kanai: Research funding from Taiho Pharmaceutical and stock ownership at Therabiopharma Inc. Tomohiro Sakuma and Hiroaki Mochizuki: employment, Mitsui Knowledge Industry. Muto Manabu: consulting or advisory role: QP, Eisai. Research funding: Olympus, Mitsui Knowledge Industry, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Chugai Pharma, Theravalues Corporation, Pfizer. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research C (17K08413) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

REFERENCES

- 1.Holter S, Borgida A, Dodd A, Grant R, Semotiuk K, Hedley D, Dhani N, Narod S, Akbari M, Moore M, Gallinger S. Germline BRCA Mutations in a Large Clinic-Based Cohort of Patients With Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3124–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.7401. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.59.7401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowery MA, Kelsen DP, Stadler ZK, Yu KH, Janjigian YY, Ludwig E, D’Adamo DR, Salo-Mullen E, Robson ME, Allen PJ, Kurtz RC, O’Reilly EM. An emerging entity: pancreatic adenocarcinoma associated with a known BRCA mutation: clinical descriptors, treatment implications, and future directions. Oncologist. 2011;16:1397–402. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0185. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golan T, Kanji ZS, Epelbaum R, Devaud N, Dagan E, Holter S, Aderka D, Paluch-Shimon S, Kaufman B, Gershoni-Baruch R, Hedley D, Moore MJ, Friedman E, et al. Overall survival and clinical characteristics of pancreatic cancer in BRCA mutation carriers. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:1132–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.418. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pihlak R, Valle JW, McNamara MG. Germline mutations in pancreatic cancer and potential new therapeutic options. Oncotarget. 2017;8:73240–73257. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17291. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.17291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lord CJ, Ashworth A. BRCAness revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:110–20. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2015.21. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc.2015.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pennington KP, Walsh T, Harrell MI, Lee MK, Pennil CC, Rendi MH, Thornton A, Norquist BM, Casadei S, Nord AS, Agnew KJ, Pritchard CC, Scroggins S, et al. Germline and somatic mutations in homologous recombination genes predict platinum response and survival in ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:764–75. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2287. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waddell N, Pajic M, Patch AM, Chang DK, Kassahn KS, Bailey P, Johns AL, Miller D, Nones K, Quek K, Quinn MC, Robertson AJ, Fadlullah MZ, et al. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2015;518:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature14169. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouche O, Guimbaud R, Becouarn Y, Adenis A, Raoul JL, Gourgou-Bourgade S, de la Fouchardiere C, Bennouna J, Bachet JB, Khemissa-Akouz F, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1011923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gill S, Ko YJ, Cripps C, Beaudoin A, Dhesy-Thind S, Zulfiqar M, Zalewski P, Do T, Cano P, Lam WY, Dowden S, Grassin H, Stewart J, et al. PANCREOX: A Randomized Phase III Study of 5-Fluorouracil/Leucovorin With or Without Oxaliplatin for Second-Line Advanced Pancreatic Cancer in Patients Who Have Received Gemcitabine-Based Chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3914–3920. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.5776. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.68.5776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oettle H, Riess H, Stieler JM, Heil G, Schwaner I, Seraphin J, Gorner M, Molle M, Greten TF, Lakner V, Bischoff S, Sinn M, Dorken B, et al. Second-line oxaliplatin, folinic acid, and fluorouracil versus folinic acid and fluorouracil alone for gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer: outcomes from the CONKO-003 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2423–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6995. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2013.53.6995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohkawa S, Okusaka T, Isayama H, Fukutomi A, Yamaguchi K, Ikeda M, Funakoshi A, Nagase M, Hamamoto Y, Nakamori S, Tsuchiya Y, Baba H, Ishii H, et al. Randomised phase II trial of S-1 plus oxaliplatin vs S-1 in patients with gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:1428–34. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.103. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poplin E, Feng Y, Berlin J, Rothenberg ML, Hochster H, Mitchell E, Alberts S, O’Dwyer P, Haller D, Catalano P, Cella D, Benson AB. Phase III, Randomized Study of Gemcitabine and Oxaliplatin Versus Gemcitabine (fixed-dose rate infusion) Compared With Gemcitabine (30-minute infusion) in Patients With Pancreatic Carcinoma E6201: A Trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:3778–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9007. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2008.20.9007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kou T, Kanai M, Yamamoto Y, Kamada M, Nakatsui M, Sakuma T, Mochizuki H, Hiroshima A, Sugiyama A, Nakamura E, Miyake H, Minamiguchi S, Takaori K, et al. Clinical sequencing using a next-generation sequencing-based multiplex gene assay in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Sci. 2017;108:1440–6. doi: 10.1111/cas.13265. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.13265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shindo K, Yu J, Suenaga M, Fesharakizadeh S, Cho C, Macgregor-Das A, Siddiqui A, Witmer PD, Tamura K, Song TJ, Navarro Almario JA, Brant A, Borges M, et al. Deleterious Germline Mutations in Patients With Apparently Sporadic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3382–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.3502. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2017.72.3502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiorean EG, Von Hoff DD, Reni M, Arena FP, Infante JR, Bathini VG, Wood TE, Mainwaring PN, Muldoon RT, Clingan PR, Kunzmann V, Ramanathan RK, Tabernero J, et al. CA19-9 decrease at 8 weeks as a predictor of overall survival in a randomized phase III trial (MPACT) of weekly nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine alone in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:654–60. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw006. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vyas O, Leung K, Ledbetter L, Kaley K, Rodriguez T, Garcon MC, Saif MW. Clinical outcomes in pancreatic adenocarcinoma associated with BRCA-2 mutation. Anticancer Drugs. 2015;26:224–6. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000178. https://doi.org/10.1097/cad.0000000000000178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yarchoan M, Myzak MC, Johnson BA, De Jesus-Acosta A, Le DT Jaffee EM, Azad NS, Donehower RC, Zheng L, Oberstein PE, Fine RL, Laheru DA, Goggins M, et al. Olaparib in combination with irinotecan, cisplatin, and mitomycin C in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:44073–81. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17237. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.17237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalia SS, Adelman K, Bale SJ, Chung WK, Eng C, Evans JP, Herman GE, Hufnagel SB, Klein TE, Korf BR, McKelvey KD, Ormond KE, Richards CS, et al. Recommendations for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing, 2016 update (ACMG SF v2.0): a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med. 2017;19:249–55. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.190. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2016.190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kou T, Kanai M, Matsumoto S, Okuno Y, Muto M. The possibility of clinical sequencing in the management of cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016;46:399–406. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyw018. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyw018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L, Shankar L, Dodd L, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.