Abstract

The parabrachial nucleus (PBN), which is located in the pons and dissected by one of the major cerebellar output tracks, is known to relay sensory information (visceral malaise, taste, temperature, pain, itch) to forebrain structures including the thalamus, hypothalamus and extended amygdala. The availability of mouse lines expressing Cre-recombinase selectively in subsets of PBN neurons and of Cre-dependent viruses that allow circuit mapping and manipulation of neuron function is beginning to reveal the connectivity and functions of PBN’s component neurons. This review focuses on the PBN neurons that express calcitonin gene-related protein (CGRPPBN) that play a major role in regulating appetite and transmitting real or potential threat signals to the extended amygdala. The functions of other specific PBN neuronal populations are also discussed. This review aims to encourage investigation of the numerous unanswered questions that are becoming accessible.

Keywords: Anorexia, Calcium imaging, Fear and taste conditioning, Threats

The parabrachial nucleus

All animals are subjected to a variety of threats to homeostasis or even to their survival, and they mount physiological and behavioral responses to counteract those threats. Homeostatic threats such as eating too much or not breathing frequently enough activate feedback systems that curtail eating or promote breathing, respectively. Threats such as food poisoning promote nausea and vomiting, while infection and inflammation elevate body temperature and promote lethargy. Cancers and other chronic diseases elicit malaise. Pain from wounds, shocks, or burns initiates a withdrawal response followed by malaise. Obnoxious odors, tastes, sounds, and sights elicit avoidance responses. The perception of wellness or threatening conditions—interoception—is the basis of feelings [1]. The initial responses to threats are innate. During the course of their lifetime, animals learn from threat events and their associated cues to avoid similar situations in the future. The hard-wired neural circuits that are activated by threatening events have been the subject of investigation for decades. The emergence of techniques to target specific neurons, visualize their axons, and manipulate their function has permitted detailed delineation of critical circuits and establishment of their importance in mediating threatening events. This review aims to document the growing realization that specific neurons within the parabrachial nucleus (PBN) relay a wide variety of noxious sensory stimuli to forebrain structures. These neurons and associated pathways are therefore critical for both responding to those stimuli and learning to avoid them. This review focuses on rat and mouse studies that interrogate the function of specific neuron sub-types—information that is generally non-existent for other mammals; consequently, extrapolation of the results obtained using rodents to other species is tenuous. However, it is noteworthy that the PBN neurons expressing CGRP, which are the focus of this review, have been mapped in human tissue [2].

The logic of neural-circuit mapping is straightforward and in principle can be applied to any animal (Box 1). The first step requires identification of specific neurons. That effort has been greatly facilitated by large-scale application of immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization techniques to reveal the expression pattern of specific genes. Genes encoding transcription factors involved in neuronal specification, as well as neuromodulators and their receptors have been particularly useful to distinguish subsets of neurons. Gene targeting in embryonic stem cells is used to direct the expression of Cre (or similar) recombinase to genes that have distinct expression patterns. This strategy is well developed in mice but is becoming accessible in other species with the advent of more powerful gene-targeting strategies. The expression of Cre recombinase is generally innocuous on its own, but it allows activation of Cre-dependent viruses that are stereotaxically delivered to brain regions where Cre-recombinase is expressed. There is a growing toolkit of viruses [3] that allow visualization of the neurons and their axonal processes, as well as identification of neurons that are upstream and downstream of the neurons that express Cre recombinase. These anatomical tracing experiments are conceptually similar to techniques that have been used for decades, with the advantage of cell-type specificity. There are also viruses that allow Cre-dependent expression of genes for selective activation or inhibition of neurons. Selective neuron activation by optogenetic or chemogenetic means (Box 1) allows one to determine whether the Cre-expressing neurons are sufficient to elicit a specific physiological or behavioral response, whereas their inactivation allows one to determine if the neurons are necessary for a normal physiological response. The combination of sufficiency and necessity experiments provides compelling evidence that the neurons under consideration are not only capable of mimicking a normal response but also physiologically relevant. Application of these techniques as applied to the PBN is featured in this review.

Box 1. Basic strategy for manipulating specific neuronal populations in the mouse.

This box provides a brief overview of Cre/loxP mediated combinatorial genetic approaches for neuronal circuit interrogation. The basic strategy for generating Cre-driver lines involves either (A) targeting Cre recombinase to a gene of interest in embryonic stem cells, such that Cre is under the control of the endogenous gene locus, or (B) recombineering a BAC clone such that Cre is under the control of the gene of interest, and then making transgenic mice by pronuclear injection [3, 122, 123]. Cre recombinase expression by itself is innocuous. For tracing analyses and anatomical interrogation, once Cre-driver mice are available, one can cross them with a fluorescent reporter line of mice, so that Cre turns on expression of the fluorescent reporter specifically in cells expressing the gene of interest by removing a loxP-flanked stop sequence [124]. Fluorescence of the reporter usually reveals the location of cell bodies and sometimes the axonal/dendritic processes; however, sometimes the reporter reveals cells that expressed the Cre-driver gene only during development, whereas expression of the gene may have decayed later in life. Nevertheless, one can visualize or manipulate the cells that express Cre in the adult by injection of virus with a Cre-dependent gene encoding an effector protein. These viruses (typically adeno-associated viruses) have a promoter suitable for neuronal expression followed by the effector gene that is flanked by double loxP sites (referred to here as DIO) and inserted backwards relative to the promoter [3, 122, 123]. In this case, the double loxP sites are designed and positioned to allow inversion of the effector gene followed by a deletion event that effectively locks the effector gene in the correct orientation for expression. Some commonly used effector genes encode: fluorescent proteins for visualization of neurons and their processes; opsins for activation or inactivation of neurons; G-protein-coupled, designer receptors that are activated by designer drugs (DREADDs) that allow activation or inactivation of neurons in response to synthetic ligands; and toxins that inactivate neurons (e.g. tetanus toxin) or kill them (e.g diphtheria toxin) [3, 122, 124]. Abbreviations of viruses used in studies discussed in this article include:

AAV-DIO-ChR2 (Adeno-associated virus with Cre-dependent channelrhodopsin); Laser- light activates neurons. There are also opsins and other proteins that inhibit neuron activity in response to light.

AAV-DIO-hM3Dq (Adeno-associated virus with Cre-dependent excitatory Gαq-coupled receptor that is activated by clozapine, the active ligand derived from clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) [125].

AAV-DIO-hM4Di (Adeno-associated virus with Cre-dependent inhibitory Gαi-coupled receptor that is activated by clozapine.

AAV-DIO-TetTox (Adeno-associated virus with Cre-dependent tetanus toxin light chain that inactivates synaptobrevin (VAMP2), which is essential synaptic vesicle fusion)

AAV-DIO-GCaMP6, which fluoresces in response to transient changes in ‘free’ calcium and is a marker of neuronal activity.

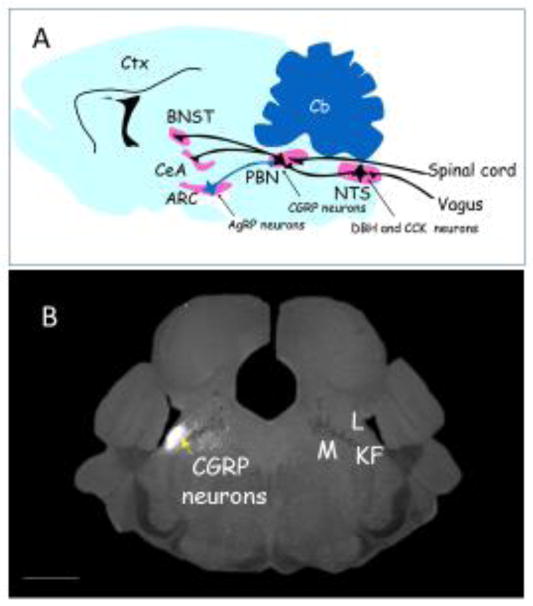

The PBN is in the rostral hindbrain at the pons-midbrain boundary and lateral to the locus coeruleus; it is dissected by the superior cerebellar peduncle (scp), a large fiber tract emanating from deep cerebellar nuclei. The scp separates the lateral PBN from the medial PBN, with the waist area being in and around the scp. Both lateral and medial regions are further subdivided into about a dozen regions [4]. Classical retrograde and anterograde labeling techniques revealed that the PBN receives axonal inputs primarily from the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) and directly from the dorsal laminae of the spinal cord [5–12] as well as from forebrain regions; neurons in the PBN project their axons to numerous forebrain regions including the thalamus, cortex, central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA), bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), and hypothalamus [13–16](Figure 1A). Thus, as a generalization, neurons within the PBN relay sensory information from the sensory neurons throughout the body to forebrain nuclei and they receive afferent feedback from those regions. Consistent with this view, electrophysiologists have recorded increased activity of PBN neurons in response to pinches, exposure to heat or cold, visceral pain, or tastes [11, 17–20]. Likewise, anatomists have measured the induction of Fos (a marker of neuronal activity) in the PBN in response to a wide variety of threats [21–26]. These experiments helped to localize neurons with responses to various stimuli to specific regions of the PBN. Induction of Fos in the external lateral PBN region has been consistently correlated with noxious somatosensory and visceral insults.

Figure 1.

Location of parabrachial CGRP-expressing neurons that function as a general alarm. A. Cartoon sagittal section of mouse brain showing the approximate locations of CGRP neurons in the parabrachial nucleus (PBN), their inputs from the spinal cord and the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) where CCK- and DBH-expressing neurons reside, and their axonal projections to the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) and the oval region of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST). All of these neurons are excitatory (glutamatergic, black) except for the inhibitory input from AgRP-expressing neurons in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) which are GABAergic (blue). The cerebellum (Cb) and cortex (Ctx) shown for reference. B. Coronal section of mouse brain showing expression of a fluorescent protein (white) in CGRP neurons (left side). The PBN has many subdivisions [4], the lateral region (L) that includes the external lateral subdivision where CGRP neurons reside, the medial region (M), the waist region that includes the superior cerebellar peduncle fibers (dark region between L and M), and adjacent lateral crest and Kölliker-Fuse regions (KF). Scale bar (bottom left): 1mm. Panel A drawn by the author; Panel B provided by Jane Chen.

CGRP neurons in parabrachial nucleus

Immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization techniques revealed selective expression of several transcription factors, neuropeptides, and receptors within the PBN that serve as starting points for making Cre-driver lines of mice that can allow delineation of circuitry and function of specific neurons within the PBN. Cre-driver mouse lines with distinct patterns of expression in the PBN are listed in Table 1. One heavily exploited line of mice has Cre recombinase targeted to the Calca gene (CalcaCre) that encodes both calcitonin, which is expressed in the thyroid, and calcitonin gene-related protein (CGRP), which is expressed in the nervous system [27]. Calcitonin and CGRP are derived by differential splicing of a common transcript [28] and they activate distinct G-protein-coupled receptors, encoded by the Calcr and Calcrl genes, respectively. Both receptors require an additional single-pass, membrane protein (RAMP) and an intracellular protein for optimal activation of adenylate cyclase [29, 30]. One population of CGRP-expressing neurons (CGRPPBN neurons) resides within the external lateral region of the PBN (Figure 1B) and they project their axons primarily to the ‘nociceptive’ lateral capsule region of the CeA and the oval nucleus of the BNST, with smaller projections to other parts of the extended amygdala, gustatory thalamus, insular cortex, and lateral hypothalamus [31]. In addition to CGRP, some of these glutamatergic neurons express other neuropeptides; thus, they have broad signaling potential. The roles of CGRP and PACAP released from PBN neurons in mediating affective pain is established (see section on pain), but little is known about the roles of other PBN neuropeptides listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Genetic markers enriched in the PBN and available Cre-driver lines of mice

| Transcription factors | ||

|---|---|---|

| Foxp2 | Foxp2-IRES-Cre:GFP (Palmiter, JAX)*† | |

| Lmx1b | Lmx1b-Cre:ERT2 (Johnson) | |

| Satb2 | Satb2-IRES-Cre:GFP (Palmiter, JAX) | |

| Neuropeptides | ||

| Calcitonin gene-related protein | Calca-Cre:GFP (Palmiter) | |

| Calca-CreERt (Chuang) | ||

| Calca-FLP-Cre:GFP (Palmiter)** | ||

| Cholecystokinin | Cck-IRES-Cre (Huang, JAX) | |

| Corticotropin releasing hormone | Crh-IRES-Cre (Zeng, JAX) | |

| Neurotensin | Nts-IRES-Cre (Myers, JAX) | |

| Prodynorphin | Pdyn-IRES-Cre:GFP (Palmiter; Lowell, JAX) | |

| Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide (PACAP) | Adcyap1-IRES-Cre (Lowell, Zeng, JAX) | |

| Tachykinin 1 (substance P) | Tac1-IRES-Cre (Zeng; JAX) | |

| Proenkephalin | Penk-IRES-Cre (Zeng; JAX) | |

| Receptors | ||

| Bombesin subtype 3 receptor | Brs3-IRES-Cre:GFP (Palmiter, JAX) | |

| Corticotropin releasing protein receptor 1 | Crhr1-IRES-Cre:GFP (Palmiter) | |

| Crhr1-IRES-FLP-Cre:GFP (Zweifel) | ||

| Leptin receptor | Lepr-Cre (Myers, JAX) | |

| Mu opioid receptor | Oprm1- Cre:GFP (Palmiter) | |

| Melanocortin 4 receptor | Mc4r-2A-Cre (Lowell) | |

| Neuropeptide Y receptor 1 | Npy1r-Cre:GFP (Palmiter, JAX | |

| Oxytocin receptor | Oxtr-IRES-Cre:GFP (Palmiter, JAX) | |

| G-protein couple receptor 88 | Gpr88-Cre:GFP (Palmiter, JAX) | |

| Tachykinin 1 receptor | Tacr1-IRES-Cre:GFP (Palmiter) | |

| Other | ||

| Cerebellin 4 | Cbln4-IRES-FLP-Cre:GFP (Zweifel) | |

IRES, internal ribosome entry site

JAX, available from Jackson Laboratory

FLP, FLP recombinase-dependent Cre

CGRPPBN neurons, anorexia, and satiety

The observation that ablation of neurons in the arcuate hypothalamus that express agouti-related protein (AgRP) results in a starvation phenotype [32] supported their importance as hunger-promoting neurons [33, 34]. Our efforts directed towards understanding the mechanism underlying the starvation phenotype led to the PBN and the generation of CalcaCre mice (see Box 2), which allowed Cre-dependent expression of either AAV-DIO-ChR2 or AAV-DIO-hM3Dq in CGRPPBN neurons [31]. Photoactivation of CGRPPBN neurons in hungry mice inhibited feeding, which resumed when photoactivation ceased. Likewise, chronic activation of the excitatory DREADD with CNO (twice daily for several days) inhibited feeding resulting in a starvation phenotype. In contrast, inhibition of CGRPPBN neurons by injection of CalcaCre mice with the inhibitory DREADD, hM4Di, with chronic delivery of CNO prevented starvation after ablation of AgRP neurons [31]. These results, along with other experiments, indicate that the hyperactivity of CGRPPBN neurons in adult mice promotes a starvation phenotype when AgRP neurons are ablated [35]; however, it is possible that hyperactivity of other PBN neurons may result in a similar phenotype. Subsequent experiments indicated that just the loss of GABA signaling by AgRP neurons results in severe anorexia [36]. Although ablation of AgRP neurons in adult mice results in starvation, mice can adapt to their loss with pharmacological or genetic intervention and live remarkably well without them [37–40]. While the loss of inhibition from AgRP neurons onto CGRPPBN neurons promotes anorexia, enhancing the activity of AgRP neurons onto CGRPPBN neurons can suppress the anorexia associated with visceral malaise [41].

Box 2. Discovery of the AgRP→CGRP neuron circuit.

Although parabrachial CGRP-expressing neurons have been known since the early 1980s [126], our research leading to them started when we inactivated the gene encoding neuropeptide Y (NPY) [127]. NPY was thought to be necessary for feeding because injection of NPY into hypothalamus of rodent brains promoted robust feeding [128]. Surprisingly, Npy gene inactivation had no effect on feeding or body weight, suggesting that compensation was involved [129]. The discovery that the NPY-expressing neurons in the arcuate hypothalamus also express agouti-related protein (AgRP), which also promoted robust feeding, suggested that it might allow mice to adapt to loss of NPY. However, inactivation of both Npy and Agrp genes also had no effect on body weight regulation [130]. These AgRP neurons use GABA as a transmitter; but, genetic disruption of GABA signaling resulted in only a small reduction in body weight [131]. Consequently, the function of the NPY/AgRP/GABA-expressing neurons was in doubt, whereas extensive research revealed that the neighboring neurons that express proopiomelanocortin (POMC) were important regulators of body weight because inactivation of the Pomc gene or one of its receptors (melanocortin 4 receptor, Mc4r) led to obesity in both mice and people [132]. To determine whether AgRP neurons were important regulators of feeding behavior, the human diphtheria toxin (DT) receptor was targeted to the Agrp locus [32]. Injection of DT into adult mice led to the ablation of AgRP neurons and within 6 days the mice gradually stopped eating, lost 20% of their body weight, and would have starved without intervention [32]. Application of optogenetic and chemogenetic technologies to AgRP neurons has supported their role in regulation of food intake. For example, injection of AgrpCre mice with AAV-DIO-ChR2 followed by photoactivation of these neurons resulted in robust feeding [56]. Mice ate as much in an hour as they would normally consume after an overnight fast. Likewise, injecting AgrpCre mice with AAV-DIO-hM3Dq, and then chronically administering the activator ligand, clozapine-N-oxide (CNO), led to substantial weight gain [133]. Although ablation of AgRP neurons in adult mice results in a starvation phenotype, mice can adapt to their loss with pharmacological or genetic intervention and live remarkably well without them [37–40].

The question then became, why do mice starve after AgRP-neuron ablation? At first, it was assumed that the loss of inhibition onto the POMC neurons was the likely explanation for the starvation phenotype because the POMC neurons receive direct inhibition from AgRP neurons; hence, loss of that inhibition should enhance the activity of POMC neurons and suppress food intake. However, ablating AgRP neurons in mice in which signaling by α-MSH derived from POMC neurons was blocked (using Ay mice that express a natural antagonist of α-MSH signaling) did not prevent starvation [134]. Then we hypothesized that the sudden loss of GABA inhibition from AgRP neurons in adult mice could result in unopposed excitation of some other neuronal population to promote the starvation phenotype. That hypothesis was tested by chronic delivery of an indirect GABA agonist (bretazenil, a benzodiazepine-like molecule) while inactivating the AgRP neurons, with the idea that systemic supplementation of GABA signaling might prevent starvation. Indeed, that strategy prevented starvation and, remarkably, after the minipump delivering the GABA agonist was depleted, the mice continued to eat [35]. Subsequently, the GABA agonist was bilaterally delivered directly into several brain regions where Fos induction had been observed after AgRP neuron ablation. Among these, only delivery of bretazenil into the PBN was able to mimic the effect of systemic delivery [35]. Because Fos expression was induced in the external lateral region of the PBN, where according to the Allen Institute brain atlas the Calca gene was robustly expressed, Cre recombinase was targeted to the Calca locus to make CalcaCre mice [31]. Those mice allowed the investigation into the connectivity and function of CGRP-expressing neurons as described in this review.

Fos is induced in the PBN [24] including the CGRP neurons [42] after a large meal, suggesting that their activation may facilitate meal termination. Indeed, mice with CGRPPBN neurons inactivated by tetanus toxin eat larger meals [42]. To obtain better resolution of neuronal activity, a virus expressing a fluorescent protein that is activated by calcium (AAV-DIO-GCaMP6) was expressed in CGRPPBN neurons and a lens was implanted over the PBN. Attaching a camera to the lens allowed the calcium activity of numerous CGRPPBN neurons to be captured simultaneously every 200 ms while a mouse was feeding. The fluorescence of CGRPPBN neurons decreased when a familiar food pellet was delivered to the cage of a hungry mouse; it also declined prior to every bite—changes conducive to feeding [43]. However, over the next hour of feeding, the activity of CGRPPBN neurons gradually increased, as anticipated by the Fos experiments and consistent with their role in meal termination. Virtually all of the CGRPPBN neurons responded to a meal [43]. Interestingly, when a highly palatable food pellet was added to the cage for the first time, the fluorescence of CGRPPBN neurons increased and the mice were slow to consume it [43]. This rise in activity correlates with neophobia, a natural response to novelty that protects animals from ingesting potentially harmful food. With further experience, CGRPPBN neuron responses to novel food mimicked the responses to normal chow. Inactivation of CGRPPBN neurons with tetanus toxin mitigated the reluctance of mice to consume a novel food, indicating that these neurons play a role in protecting mice from potential threats. Note that the threat in this case is only perceived to be dangerous; consequently, the CGRPPBN neurons can respond to central inputs, as well as peripheral inputs.

The hypothesis accounting for the starvation phenotype when inhibitory AgRP neurons are ablated called for unopposed excitation of CGRPPBN neurons [35]. Based on anatomical studies, a likely source of the excitation was predicted to be the NTS (Figure 1). Indeed, partial inactivation of glutamate signaling by the NTS neurons or inactivation of NMDA receptors in the PBN prevented starvation when AgRP neurons were ablated [38]. Two specific neuronal populations in the NTS, noradrenergic, dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH)-expressing neurons and cholecystokinin (CCK)-expressing neurons, both of which are also glutamatergic, were shown to make direct excitatory contacts onto CGRPPBN neurons [44]. Either chemogenetic activation of their cell bodies (hM3Dq plus CNO) or photoactivation (ChR2) of their axon terminals in the PBN was sufficient to inhibit feeding and promote weight loss [44]. Thus, a basic tenet of the hypothesis was confirmed.

The CCK and DBH neurons, along with other NTS neurons, are activated by the vagal sensory fibers that innervate the gastrointestinal tract and signal satiety [45, 46]. Ingestion of a large meal activates vagal mechanoreceptors in the stomach and stimulates release of peptides such as CCK and GLP1 from the intestinal neuroendocrine cells, which activate distinct populations of vagal afferents [47]. Consequently, vagal stimulation by a meal activates a feedback circuit that inhibits feeding. Consistent with this view, chronic inactivation of CGRPPBN neurons with tetanus toxin resulted in larger meals and allowed unrestrained food consumption when AgRP neurons were activated by ChR2 photostimulation [42]. The ability of CCK, GLP1, or leptin to decrease food consumption was attenuated when CGRPPBN neurons were inactivated [42]. These results indicate that CGRPPBN neurons respond to vagal stimulation and play an important role in satiety.

Interestingly, gastric bypass surgery activates the CGRPPBN neurons [48], suggesting that these neurons may play a role in the loss of appetite and weight loss resulting from this surgery [49, 50]. Meals rich in fiber also promote satiety by facilitating gut bacteria to produce short-chain fatty acids that activate intestinal gluconeogenesis and stimulate spinal (rather than vagal) afferent signals to suppress appetite [51]. The central neurons involved in suppressing appetite in response to fiber have not been characterized, but CGRPPBN neurons are reasonable candidates.

Meal cessation had been thought to be mediated by the arcuate POMC neurons [52]. Although they clearly provide long-term control of body weight [53, 54], direct photoactivation of POMC neurons expressing ChR2 only affects feeding behavior after many hours [55, 56]. The recent discovery of another population of glutamatergic, arcuate neurons that rapidly suppresses appetite fills an important niche in the regulation of feeding behavior [34, 57]. Those neurons project their axons to the same hypothalamic targets as POMC and AgRP neurons. Thus, both arcuate and parabrachial pathways can mediate satiety.

CGRPPBN neurons and visceral malaise

The vagus is activated not only by a meal but also by more extreme conditions such as visceral malaise induced by food poisoning [58]. Toxins, bacteria, or other pathogens can activate the vagus more vigorously than a meal resulting in nausea and vomiting in some species (but not rodents). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), derived from bacterial cell walls, is a potent activator of vagal toll-like receptor 4 [59] while other pathogens may stimulate release of serotonin which activates immune cells and sensory fibers [60, 61]. Peritoneal injection of low doses of LPS or high doses of LiCl, which mimic bacterial infection and nausea in rodents, promotes anorexia and induces Fos in both NTS and CGRPPBN neurons [31, 62]. Suppression of nausea with serotonin 5HT3 receptor antagonists (ondansetron) protects against hyperactivity of CGRPPBN neurons [37]. LPS can completely suppress food intake driven by AgRP-neuron activation [64], but activating AGRP neuron terminals in the PBN does not suppress anorexia induced by LPS [41], suggesting that there are additional pathways by which LPS promotes anorexia. Widespread bacterial infection (sepsis) can promote severe anorexia and induce expression of the CGRP precursor in many organ systems [65]. It is likely that ingestion of most toxic substances that induce malaise and/or nausea activate the vagal→NTS→CGRPPBN circuit. The phenomenon of conditioned-taste aversion (CTA) is experimentally created by pairing the ingestion of a novel food (e.g., saccharin, sucrose, or Ensure) with injection of LiCl [66, 67]. After this pairing, rodents avoid consuming the novel food. CTA of equivalent magnitude can be generated by pairing photoactivation of CGRPPBN neurons with presentation of Ensure [63]. Thus, mice learned to avoid Ensure because their CGRPPBN neurons had been activated—resulting in a memory of nausea that never really happened. Furthermore, inactivation of CGRPPBN neurons by activation of hM4Di with CNO or by tetanus toxin was sufficient to attenuate establishment of CTA [63].

Chronic diseases as well as a variety of cancers can promote cachexia, a condition that often includes anorexia, lethargy, malaise, and muscle wasting [68]. The molecular mediators of the cachexia phenotype include hormone-like molecules, e.g., GDF15 and activin A-like molecules [69–71] as well as various cytokines (tumor necrosis factor and interleukins 1 and 6) released by an activated immune system [72]. These signaling molecules can activate spinal or vagal afferents or act directly on NTS neurons. Nociceptive sensory fibers also signal to the spinal cord and then to CGRPPBN neurons as described below. Transplantable tumors (e.g., Lewis lung carcinoma) or a genetic tumor model (Apcmin mice) robustly activate Fos in CGRPPBN neurons as the tumors progress [73]. Importantly, inactivation of CGRPPBN neurons mitigates the anorexia as well as the lethargy and malaise associated with cancer progression [74]. Cisplatin chemotherapy promotes nausea and activates CGRPPBN neurons [74]; thus, cancer treatment can activate the same anorexia system as the primary tumor. These observations suggest that anorexia associated with other chronic conditions, perhaps even normal aging, may also be mediated by CGRPPBN neurons.

CGRPPBN neurons and pain

Pain is a very effective teacher. Animals readily learn to avoid conditions that elicit pain; they learn to associate environmental cues (conditioned stimulus, CS) with pain (unconditioned stimulus, US) and will either freeze or flee, depending on the circumstances, when presented with the CS in the future—a phenomenon referred to a ‘fear conditioning’ [75]. In a series of experiments, Bernard and coworkers demonstrated by electrophysiological recordings in the PBN of anesthetized rats that both somatic pain (heat and pinches) and visceral pain (rectal balloon) activate neurons in the external lateral PBN [11]. Anatomical tracing revealed a major pathway from the dorsal laminae of the spinal cord to the PBN and from there to the lateral capsule of the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeAlc), referred to as the spino-parabrachial-amygdaloid pathway [11]. CGRP in the CeAlc is depleted after surgical PBN ablation [76]. CGRP enhances synaptic plasticity in the CeAlc [77, 78] and infusion of CGRP directly into the amygdala elicits freezing behavior [79]. PACAP is co-expressed with CGRP in some PBN neurons and it also plays a role in mediating the emotional aspects of pain [80]. These observations suggested that CGRPPBN neurons mediate the US in classical fear conditioning in which a foot shock is paired with a tone in a novel environment [81]. Indeed, foot shocks induced Fos in most CGRPPBN neurons [82] and monitoring GCaMP6 fluorescence in CGRPPBN neurons revealed that they are rapidly activated by a foot or tail shock in an intensity-dependent manner [43]. Pairing ChR2 photoactivation of CGRPPBN neurons with a novel environment or a tone, was sufficient to establish a fear memory [82]. Inactivation of CGRPPBN neurons with tetanus toxin substantially attenuated development of a foot-shock-induced fear memory [82], indicating the necessity of CGRPPBN neurons for optimal fear learning or its expression. In the absence of functional CGRPPBN neurons, the threat signal (US) never reaches the downstream CeAl neurons and hence the association of the CS with the US is attenuated. Interestingly, after pairing a tone (CS) with a foot shock (US), exposing the animal to the tone alone is sufficient to activate CGRPPBN neurons [43]. Thus, after condition the CS becomes a potential threat by activating a US pathway. Foot shocks also activate neurons in other brain regions, including the neighboring basolateral amygdala (BLA), which has traditionally been the brain region where the US signal was thought to converge with the CS to establish a fear memory [75, 83, 84]. Recent data suggest that the US signal may reach the BLA indirectly from the CeA [85, 86], but there may be additional circuits that mediate the US signal [87].

Exposing a mouse tail to hot water of increasing temperatures also activated nearly all CGRPPBN neurons when temperature exceeded 44°C [43]. Exposing the tongue to a warm metal rod or treatment of the face with formalin or capsaicin also activated CGRPPBN neurons [43, 88] resulting in aversive behaviors and distress vocalizations [88]; thus, both spinal and trigeminal nerve pathways impinge on CGRPPBN neurons. There is direct innervation of CGRPPBN neurons by the trigeminal as well as an indirect pathway [88]. Itch-inducing compounds, such a chloroquine, activate G-protein coupled receptors on sensory neurons [89] and stimulated GCaMP6 calcium fluorescence of nearly all CGRPPBN neurons [43], while inactivating the lateral PBN or CGRPPBN neurons greatly reduced the scratching response to chloroquine [43, 90].

Chronic inflammatory pain induced by injection of formalin into the paw is attenuated by hunger, whereas acute pain responses are not. Optogenetic activation of the AgRP-neuron projection to the lateral PBN is sufficient to completely suppress inflammatory pain and this effect is blocked by an antagonist to the NPY1 receptor [91]. The specific PBN neurons that respond to NPY in this assay have not been identified, but CGRPPBN neurons are likely contributors because release of CGRP in the CeA potentiates inflammatory pain [77, 78].

CGRPPBN neurons are activated by many sensory modalities

In addition to spinal and visceral (via NTS) inputs to CGRPPBN neurons, there is evidence that asphyxia—a common threat to people with sleep apnea—activates CGRPPBN neurons [92]. This phenomenon is studied by exposing rodents to hypercapnia (high CO2), which induces Fos in the lateral PBN [93]. Afferent inputs that activate the CGRPPBN neurons in response to hypercapnia arise from the respiratory part of the NTS and the retrotrapezoid nucleus [92–94]. Photo-inactivation studies revealed that the CGRPPBN neurons relay the life-threatening aspect of hypercapnia to the extended amygdala including the substantia innominata and CeA to promote arousal [93]. Other experiments have revealed that all sensory modalities tested (bitter taste, moving object, loud noise, fox odor, vestibular disturbance) induce Fos in the lateral PBN, including CGRPPBN neurons, and inactivating CGRPPBN neurons with tetanus toxin ameliorates the behavioral responses to these sensory stimuli [95–97 and our unpublished observations]. The neural circuits that allow each of these sensory modalities to activate CGRPPBN neurons remain to be elucidated. Thus, CGRPPBN neurons receive inputs not only from the periphery but also (indirectly) from most, if not all, primary sensory systems. As a consequence, mice with inactive CGRPPBN neurons are relatively fearless.

Functions of other PBN neurons

The CGRPPBN neurons represent a small proportion of the neurons in the PBN (Figure 1B), indicating that there are many additional populations waiting to be identified and characterized; they very likely play important roles in relaying a wide variety of sensory information. Taste: Each of the tastes (sweet, sour, bitter, umami, and salty) is relayed from the tongue to the gustatory NTS and from there to the PBN and then on to the thalamus and cortex [98–100]. Activity of neurons in the waist area of the PBN was detected by electrophysiological recordings in anesthetized mice in response to application of tastants to the tongue [6, 19, 100]. However, the molecular identity of PBN neurons that relay taste sensations to the thalamus has not been reported. Water and salt intake: PBN neurons are also involved in maintaining water and salt balance [101]. Salt appetite—the desire to consume high concentrations of NaCl, which occurs after salt depletion—activates lateral PBN neurons via input from mineralocorticoid-sensitive neurons in the NTS [102]; those PBN neurons express the transcription factor FoxP2, but their role in mediating salt appetite is unclear [103, 104]. The lateral PBN includes neurons that express the oxytocin receptor (OxtrPBN neurons) that regulate water intake [105]. Chemogenetic activation of OxtrPBN neurons inhibits drinking by thirsty mice but has no effect on food intake [105]. Conversely, inactivation of OxtrPBN neurons promotes drinking. These OxtrPBN neurons project axons to several brain regions involved in fluid intake and they receive direct excitatory input from oxytocin neurons in the paraventricular nucleus, CCK-expressing neurons in the NTS, as well as unidentified NTS neurons [105]. Food intake: In addition to the CGRPPBN neurons (discussed above), other neurons in the lateral PBN that receive excitatory input from the MC4R-expressing paraventricular hypothalamic neurons mediate satiety [106], but their molecular identity has not been described. Their activation is rewarding, whereas activation of CGRPPBN neurons is aversive [106, 107]. Inhibition of undefined lateral PBN neurons by GABAergic projections from the CeA that express the serotonin receptor Htr2a gene promotes feeding, perhaps as part of a feedback circuit [108]. Glucose homeostasis: Activation of glucose-sensing neurons in the lateral PBN that express CCK and the leptin receptor helps to initiate counter-regulatory responses that maintain glucose levels during starvation and in response to noxious stimuli [109–111]. Temperature regulation: The behavioral and physiological responses to non-noxious heat and cold are relayed by two distinct populations of neurons in the PBN that project their axons to the preoptic area [112]. Their activation stimulates movement to a preferred temperature zone and stimulates physiological responses, e.g. heat generation (activation of brown fat, shivering) or heat conservation (vasoconstriction). Neurons in the PBN that respond to skin warming express Foxp2 and Pdyn genes and project their axons to the preoptic area; they may be critical mediators of thermoregulation [113]. The identity of PBN cold-responsive neurons has not yet be elucidated. Cardiac function: activation of unidentified lateral PBN neurons modulates cardiac function [114]. Breathing: glutamatergic neurons in the lateral crescent of the PBN and adjacent Kölliker-Fuse nucleus are activated in response to hypercapnia and project their axons to medullary regions involved respiratory control [115, 116]. These neurons, like the CGRPPBN neurons, receive inputs from the retrotrapezoid nucleus [92–94]. Hypoxia also activates lateral crescent and Kölliker-Fuse neurons and ablation of these regions impairs respiratory responses [117]. These hypoxia-sensitive neurons receive excitatory inputs that are initially detected by carotid body chemoreceptors. The wide variety of sensory inputs that are transmitted by different neuron populations in the PBN and neighboring Kölliker-Fuse suggests that cross-talk between these different neurons may help to orchestrate appropriate physiological responses, a promising area for future investigation.

Concluding remarks

The CGRPPBN neurons appear to be involved in not only terminating a meal—a physiological response to food in the stomach and intestine—but also alerting the forebrain, especially the CeAlc and BNST, about a wide variety of threats ranging from visceral malaise, to pain and itch, to cues associated with potential threats. They provide reliable excitation of their targets with dense basket synapses on the soma of post-synaptic cells in the CeAlc [118]. Fos studies left open the possibility that distinct sub-populations of CGRPPBN neurons are activated selectively by different threats because Fos expression was never activated in all CGRPPBN neurons [31, 42, 82]. However, the more sensitive calcium-imaging method revealed that essentially all CGRPPBN neurons are activated by every threat examined [43]. The CGRPPBN neurons are glutamatergic and at least some of them express other excitatory neuropeptides (PACAP, tachykinin 1, neurotensin, corticotropin releasing hormone) in addition to CGRP (based on mRNAs enriched in polysomes from CGRP neurons [119]). Thus, CGRPPBN neurons, probably along with other PBN neurons, serve as a general alarm system, alerting the forebrain of real or potential threats [120]. These observations raise many questions (see Outstanding Questions box) including the obvious issue of how mice use this alarm signal to orchestrate appropriate behavioral and physiological responses to distinct stimuli. One idea is that weak activation of CGRPPBN neurons (e.g. following a large meal) promotes satiety, while more activation (e.g. in visceral malaise) promotes anorexia, and even greater activation (e.g. in response to foot shock) promotes freezing behavior. Low frequency photoactivation of CGRPPBN neurons promotes conditioned taste aversion and anorexia without freezing while higher frequency stimulation promotes both. Likewise, photoactivation of CCK or DBH axon terminals in the PBN inhibits feeding without inducing freezing behavior [44]. Discrimination of the source of the stimulation presumably depends on alternative sensory pathways that likely to pass through the thalamus and cortex. Mounting an appropriate response to a threat would then depend on convergence of CS and US signals in downstream nuclei, perhaps in the extended amygdala.

Outstanding Questions.

If CGRPPBN neurons are blind to the source of the excitatory input and thus serve as a general alarm to alert mammals of real or potential threats, then how do mammals mount appropriate behavioral and/or physiological responses to specific threats?

Are there additional PBN neurons that relay threat signals and, if so, how do they differ from the CGRPPBN neurons?

Are there PBN neurons that relay the pleasurable signals and, if so, what are their downstream targets?

Some excitatory and inhibitory inputs to specific PBN neurons are known, but there are many more that need to be delineated. In particular, how do sensory cues that were associated with pain activate CGRPPBN neurons after conditioning?

Can pharmacological approaches be developed that target the CGRPPBN to the extended amygdala circuit to treat eating, pain and/or anxiety disorders?

Do neurons within the PBN communicate with each other, either directly, or via feedback loops, and if so, for what purpose?

Most specific populations of PBN neurons innervate several forebrain regions. Are the inputs to each of those brain regions coordinated to produce optimal behavioral responses?

What is the molecular identity of PBN neurons that relay each of the five taste sensations to the thalamus?

Because CGRPPBN neurons are activated by all painful stimuli tested, including those transmitted by dorsal root ganglia/spinal cord, vagus, and trigeminal neurons, and given that the activity of CGRPPBN neurons promotes affective responses and anorexia, these neurons, along with neighboring neurons in the external lateral PBN are strong candidates for contributing to many human disorders related to pain and anorexia. The role of CGRPPBN neurons in mediating the anorexia and behavioral malaise associated with cachexia provides a nice example of how these neurons contribute to disease and suggest a potential target for therapeutic intervention [43]. A compelling case can be made that CGRPPBN-neuron projections to the extended amygdala mediate chronic pain [77, 78], including migraine [88, 121], and that this circuit likely contributes to a variety of anxiety disorders.

Highlights.

The parabrachial nucleus relays sensory information to the forebrain. Some functions of a few genetically identified parabrachial neurons have been delineated.

CGRPPBN neurons relay a wide variety of aversive signals (e.g., food poisoning, pain, itch, and hypercapnia) to the central nucleus of the amygdala, the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and other brain regions.

Activation of CGRPPBN neurons is necessary and sufficient to establish robust foot-shock and taste memories.

Chronic activation of CGRPPBN neurons can lead to severe anorexia and starvation.

Other PBN neurons transmit taste, temperature, respiratory, satiety, thirst, salt-appetite, or glucose counter-regulatory signals.

Acknowledgments

I thank all of the students, post-doctoral fellows and colleagues who helped make this review possible. The work in our lab was supported in part by funding from NIH (R01-DA-24908).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest related to this review.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Damasio A, Carvalho GB. The nature of feelings: evolutionary and neurobiological origins. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:143–152. doi: 10.1038/nrn3403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Lacalle S, Saper CB. Calcitonin gene-related peptide-like immunoreactivity marks putative visceral sensory pathways in human brain. Neuroscience. 2000;100:115–130. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00245-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Betley JN, Sternson SM. Adeno-associated viral vector for mapping, monitoring and manipulating neural circuits. Hum Gene Ther. 2011;22:669–677. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hashimoto K, et al. Characterization of parabrachial subnuclei in mice with regard to salt tastants: possible independence of taste relay from visceral processing. Chem Senses. 34:253–267. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjn085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ricardo JA, Koh ET. Anatomical evidence of direct projections from the nucleus of the solitary tract to hypothalamus, amygdala and other forebrain structures. Brain Res. 1978;153:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)91125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norgren R, Leonard CM. Taste pathways in rat brainstem. Science. 1971;173:1136–1139. doi: 10.1126/science.173.4002.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norgren R. Taste pathways to hypothalamus and amygdala. J Comp Neurol. 1975;166:17–30. doi: 10.1002/cne.901660103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herbert H, et al. Connections of the parabrachial nucleus with the nucleus of the solitary tract and medullary reticular formation in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1990;293:540–580. doi: 10.1002/cne.902930404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiberg M, Blomqvist A. The spinomesencephalic tract in the cat: its cells of origin and termination pattern as demonstrated by intraaxonal transport method. Brain Res. 1984;291:1–18. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90645-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cechetto DF, et al. Spinal and trigeminal dorsal horn projections to the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1985;240:153–160. doi: 10.1002/cne.902400205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gauriau C, Bernard J-F. Pain pathways and parabrachial circuits in the rat. Exp Physiol. 2001;87(2):251–258. doi: 10.1113/eph8702357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tokita K, Boughter JD., Jr Afferent connections of the parabrachial nucleus in C57Bl/6J mice. Neuroscience. 2009;161:475–488. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saper CB, Loewy AD. Efferent connections of the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. Brain Res. 1980;197:291–317. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fulwiler CE, Saper CB. Subnuclear organization of the efferent connections of the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. Brain Res Reviews. 1984;7:229–259. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(84)90012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krout KE, Loewy AD. Parabrachial nucleus projections to midline and intralaminar thalamic nuclei of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2000;18:428, 475–494. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001218)428:3<475::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernard JF, et al. The organization of efferent projections from the pontine parabrachial are to the amygdaloid complex: a Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin (PHA-L) study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1993;329:201–229. doi: 10.1002/cne.903290205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menendez L, et al. Parabrachial area: electrophysiological evidence for an involvement in cold nociception. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:2099–2116. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.5.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernard JF, et al. The parabrachial area: electrophysiological evidence for and involvement in visceral nociceptive processes. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:1646–1660. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.5.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tokita K, Boughter JD., Jr Topographic organization of taste-responsive neurons in the parabrachial nucleus of C57BL/6J mice: an electrophysiological mapping study. Neuroscience. 2016;316:151–166. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geran LC, Travers SP. Bitter-responsive gustatory neurons in the rat parabrachial nucleus. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:1598–1612. doi: 10.1152/jn.91168.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hermanson O, Blomqvist A. Subnuclear localization of FOS-like immunoreactivity in the rat parabrachial nucleus after nociceptive stimulation. J Comp Neurol. 1996;368:45–56. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960422)368:1<45::AID-CNE4>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paues J, et al. Expression of melanocortin 4 receptor by rat parabrachial neurons responsive to immune and aversive stimuli. Neuroscience. 2006;141:287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller RL, et al. Fos activation of FoxP2 and LMX1B neurons in the parabrachial nucleus evoked by hypotension and hypertension in conscious rats. Neuroscience. 2012;218:110–125. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zséli G, et al. Elucidation of the anatomy of a satiety network: Focus on connectivity of the parabrachial nucleus in the adult rat. J Comp Neurol. 2016;524:2803–2827. doi: 10.1002/cne.23992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakai N, Yamamoto T. Conditioned taste aversion and c-fos expression in the rat brainstem after administration of various USs. Neuroreport. 1997;8:2215–2220. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199707070-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thiele TE, et al. c-Fos induction in rat brainstem in response to ethanol- and lithium chloride-induced conditioned taste aversions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1023–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenfeld MG, et al. Production of a novel neuropeptide encoded by the calcitonin gene via tissue-specific RNA processing. Nature. 1983;304:129–135. doi: 10.1038/304129a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amara SG, et al. Alternative RNA processing in calcitonin gene expression generates mRNAs encoding different polypeptide products. Nature. 1982;298:240–244. doi: 10.1038/298240a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLatchie LM, et al. RAMPs regulate the transport and ligand specificity of the calcitonin-receptor-like receptor. Nature. 1998;393:333–339. doi: 10.1038/30666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poyner DR, et al. International Union Pharmacology. XXXII The mammalian calcitonin gene-related peptides, adrenomedulin, amylin, and calcitonin receptors. Pharm Rev. 2002;54:233–246. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carter ME, et al. Genetic identification of a neural circuit that suppresses appetite. Nature. 2013;503:111–114. doi: 10.1038/nature12596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luquet S, et al. NPY/AgRP neurons are essential for feeding in adult mice but can be ablated in neonates. Science. 2005;310:683–685. doi: 10.1126/science.1115524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sternson SM, et al. An emerging technology framework for the neurobiology of appetite. Cell Metab. 2016;23:234–253. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andermann ML, et al. Toward a wiring diagram understanding of appetite control. Neuron. 2017;95:757–778. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu Q, et al. Loss of GABAergic Signaling by AgRP Neurons to the Parabrachial Nucleus Leads to Starvation. Cell. 2009;137:1225–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meng F, et al. New inducible genetic method reveals critical roles of GABA in the control of feeding and metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:3645–3650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602049113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu Q, et al. Deciphering a neuronal circuit that mediates appetite. Nature. 2012;483:594–597. doi: 10.1038/nature10899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu Q, et al. Ablation of neurons expressing agouti-related protein, but not melanin concentrating hormone, in leptin-deficient mice restores metabolic functions and fertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:3155–3160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120501109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Denis RG, et al. Palatability Can Drive Feeding Independent of AgRP Neurons. Cell Metab. 2015;22:646–657. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu Q, et al. NR2B subunit of the NMDA glutamate receptor regulates appetite in the parabrachial nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:14765–14770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314137110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Essner RA, et al. AgRP Neurons Can Increase Food Intake during Conditions of Appetite Suppression and Inhibit Anorexigenic Parabrachial Neurons. J Neurosci. 2017;37:8678–8687. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0798-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campos CA, et al. Parabrachial CGRP neurons control meal termination. Cell Metab. 2016;23:811–820. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campos CA, et al. Encoding of danger by parabrachial CGRP neurons. Nature. 2017a doi: 10.1038/nature25511. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roman CW, et al. Genetically and functionally defined NTS to PBN brain circuits mediating anorexia. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11905. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berthoud HR, et al. Neuroanatomy of extrinsic afferents supplying the gastrointestinal tract. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16(Suppl 1):28–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-3150.2004.00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ritter RC. Gastrointestinal mechanisms of satiation for food. Phys Beh. 2004;81:249–273. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams EK, et al. Sensory neurons the detect stretch and nutrients in the digestive system. Cell. 2016;166:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mumphrey MB, et al. Eating in mice with gastric bypass surgery causes exaggerated activation of brainstem anorexia circuit. Int J Obes (Lond) 2016;40:921–928. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schauer PR, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes–3-year outcomes. New Engl J of Med. 2014;370:2002–2013. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Evers SS, et al. The physiology and molecular underpinnings of the effects of bariatric surgery on obesity and diabetes. Annu Rev Physiol. 2017;79:313–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-022516-034423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soty M, et al. Gut-brain glucose signaling in energy homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2017;25:1231–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morton GJ, et al. Neurobiology of food intake in health and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:367–378. doi: 10.1038/nrn3745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krudy H, et al. Severe, early-onset obesity adrenal insufficiency and red hair pigmentation caused by POMC mutations in humans. Nat Genet. 1998;19:155–157. doi: 10.1038/509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yaswen L, et al. Obesity in the mouse model of pro-opiomelanocortin deficiency responds to peripheral melanocortin. Nat Med. 1999;5:1066–1070. doi: 10.1038/12506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhan C, et al. Acute and long-term suppression of feeding behavior by POMC neurons in brainstem and hypothalamus, respectively. J Neurosci. 2013;33:3624–3632. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2742-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aponte Y. AGRP neurons are sufficient to orchestrate feeding behavior rapidly and without training. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:351–355. doi: 10.1038/nn.2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fenselau H, et al. A rapidly acting glutamatergic ARC→PVH satiety circuit postsynaptically regulated by α-MSH. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:42–51. doi: 10.1038/nn.4442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Horn CC. Measuring the nausea-to-emesis continuum in non-human animals: refocusing on gastrointestinal vagal signaling. Exp Brain Res. 2014;232:2471–81. doi: 10.1007/s00221-014-3985-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beutler B. Tlr4: central component of the sole mammalian LPS sensor. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:20–26. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)00046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Worthington JJ. The intestinal immunoendocrine axis: novel cross-talk between enteroendocrine cells and the immune system during infection and inflammatory disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2015;43:727–733. doi: 10.1042/BST20150090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bellono NW, et al. Enterochromaffin cells are gut chemosensors that couple to sensory neural pathways. Cell. 2017;170:185–198. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paues J, et al. Feeding-related immune responsive brain stem neurons: association with CGRP. NeuroReport. 2001;12:2399–2403. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200108080-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carter ME, et al. Parabrachial calcitonin gene-related peptide neurons mediate conditioned taste aversion. J Neurosci. 2015;35:4582–4586. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3729-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu Y, et al. Lipopolysaccharide rapidly and completely suppresses AgRP neuron-mediated food intake in male mice. Endocrinology. 2016;157:2380–2392. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sager R, et al. Procalcitonin-guided diagnosis and antibiotic stewardship revisited. BMC Med. 2017;15:15. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0795-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reilly S. The parabrachial nucleus and conditioned taste aversion. Brain Res Bull. 1999;48:239–254. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lin JY, et al. Conditioned taste aversions: From poisons to pain to drugs of abuse. Psychon Bull Rev. 2017;24:335–351. doi: 10.3758/s13423-016-1092-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Porporato PE. Understanding cachexia as a cancer metabolism syndrome. Oncogenesis. 2016;5:e200. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2016.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tsai VW, et al. Anorexia-cachexia and obesity treatment may be two sides of the same coin: role of the TGF-b superfamily cytokine MIC-1/GDF15. Int J Obes (Lond) 2016;40:193–197. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Winbanks CE. Smad7 gene delivery prevents muscle wasting associated with cancer cachexia. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:348ra98. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hsu J-Y, et al. Non-homeostatic body weight regulation through a brainstem-restricted receptor for GDF15. Nature. 2017;550:255–259. doi: 10.1038/nature24042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fearon KC, et al. Cancer cachexia: mediators, signaling, and metabolic pathways. Cell Metab. 2012;16:153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Campos CA, et al. Cancer-induced anorexia and malaise are mediated by CGRP neurons in the parabrachial nucleus. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:934–942. doi: 10.1038/nn.4574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Alhadeff AL, et al. Excitatory hindbrain-forebrain communication is required for cisplatin-induced anorexia and weight loss. J Neurosci. 2017;37:362–370. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2714-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Johansen JP, et al. Molecular mechanisms of fear learning and memory. Cell. 2011;147:509–524. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.D’Hanis W, et al. Topography of thalamic and parabrachial calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) immunoreactive neurons projecting to subnuclei of the amygdala and extended amygdala. J Comp Neurol. 2007;505:268–291. doi: 10.1002/cne.21495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Han JS, et al. Critical role of calcitonin gene-related peptide 1 receptors in the amygdala in synaptic plasticity and pain behavior. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10717–10728. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4112-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shinohara K, et al. Essential role of endogenous calcitonin gene-related peptide in pain-associated plasticity in the central amygdala. Eur J Neurosci. 2017;46:2149–2160. doi: 10.1111/ejn.13662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kocorowski LH, Helmstetter FJ. Calcitonin gene-related peptide released within the amygdala is involved in Pavlovian auditory fear conditioning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2001;75:149–163. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2000.3963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Missig G, et al. Parabrachial pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide activation of amygdala endosomal extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling regulates the emotional component of pain. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81:671–682. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sato M, et al. The lateral parabrachial nucleus is actively involved in the acquisition of fear memory in mice. Mol Brain. 2015;8:22. doi: 10.1186/s13041-015-0108-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Han S, et al. Elucidating an affective pain circuit that creates a threat memory. Cell. 2015;162:363–374. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Janek PH, Tye KM. From circuits to behavior in the amygdala. Nature. 2015;517:284–292. doi: 10.1038/nature14188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tovote P, et al. Neuronal circuits for fear and anxiety. Nat Review: Neurosci. 2015;16:317–331. doi: 10.1038/nrn3945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yu K, et al. The central amygdala controls learning in the lateral amygdala. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:1680–1684. doi: 10.1038/s41593-017-0009-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jiang L, et al. Cholinergic signaling controls conditioned fear behaviors and enhances plasticity of cortical amygdala circuits. Neuron. 2016;90:157–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Herry C, Johansen JP. Encoding of fear learning and memory in distributed neuronal circuits. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1644–1654. doi: 10.1038/nn.3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rodriguez E, et al. A craniofacial-specific monosynaptic circuit enables heightened affective pain. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:1734–1743. doi: 10.1038/s41593-017-0012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Han L, et al. A subpopulation of nociceptors specifically linked to itch. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:174–182. doi: 10.1038/nn.3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mu D, et al. A central neural circuit for itch sensation. Science. 2017;357:695–699. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Alhadeff AL, et al. Discovery of a neural circuit for the suppression of pain by a competing need state. Cell. 2018 Mar 23; doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kaur S, et al. A genetically defined circuit for arousal from sleep during hypercapnia. Neuron. 2017;96:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Berquin P, et al. Brainstem and hypothalamic areas involved in respiratory chemoreflexes: a Fos study in adult rats. Brain Res. 2000;857:30–40. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Guyenet PG, Bayliss AG. Neural control of breathing and CO2 homeostasis. Neuron. 2015;87:946–961. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Day HEW, et al. The pattern of brain c-fos mRNA induced by a component of fox odor, 2.5-dihydro-2,4,5-trimethylthiazoline (TMT), in rats, suggests both systemic and processive stress characteristics. Brain Res. 2004;1025:139–151. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.07.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Illing RB, et al. Transcription factor modulation and expression in the rat auditory brainstem following electrical intracochlear stimulation. Experimental Neurology. 2002;175:226–244. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Suzuki T, et al. Integrative responses of neurons in parabrachial nuclei to a nauseogenic gastrointestinal stimulus and vestibular stimulation in vertical planes. Am J Physiol Regul Intgr Comp Physiol. 2012;302:R965–975. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00680.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Travers JB, et al. Gustatory neural processing in the hindbrain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1987;10:595–632. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.10.030187.003115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yamolinsky DA, et al. Common sense about taste: from mammals to insects. Cell. 2009;239:234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Carleton A, et al. Coding in the mammalian gustatory system. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Menani JV, et al. Role of the lateral parabrachial nucleus in the control of sodium appetite. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014;306:R201–210. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00251.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Geerling JC, Loewy AD. Central regulation of sodium appetite. Exp Physiol. 2008;93:177–209. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.039891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jarvie B, Palmiter RD. HSD2 neurons in the hindbrain drive sodium appetite. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:167–169. doi: 10.1038/nn.4451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Resch JM, et al. Aldosterone-sensing neurons in the NTS exhibit state-dependent pacemaker activity and drive sodium appetite via synergy with angiotensin II signaling. Neuron. 2017;96:190–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ryan PJ, et al. A neural circuit that selectively suppresses fluid intake. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:1722–1743. doi: 10.1038/s41593-017-0014-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Garfield AS, et al. A neural basis for melanocortin-4 receptor-regulated appetite. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:863–872. doi: 10.1038/nn.4011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Roman CR, et al. A tale of two circuits: CCKNTS neuron stimulation controls appetite and induces opposing motivational states by projections to distinct brain regions. Neuroscience. 2017;358:316–324. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Douglass AM, et al. Central amygdala circuits modulate food consumption through a positive-valence mechanism. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:1384–1394. doi: 10.1038/nn.4623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Garfield AS, et al. Parabrachial-hypothalamic cholecystokinin neurocircuit controls counterregulatory responses o hypoglycemia. Cell Metab. 2014;20:1030–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Flak JN, et al. Leptin-inhibited PBN neurons enhance responses to hypoglycemia in negative energy balance. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1744–1750. doi: 10.1038/nn.3861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Flak JN, et al. A leptin-regulated circuit controls glucose mobilization during noxious stimuli. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:3103–3113. doi: 10.1172/JCI90147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Morrison SF. Central neural control of thermoregulation and brown adipose tissue. Auton Neurosci. 2016;196:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Geerling JC, et al. Genetic identity of thermosensory relay neurons in the lateral parabrachial nucleus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2016;310:R41–54. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00094.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chamberlain NL, Saper CB. Topographic organization of cardiovascular responses to electrical and glutamate microstimulation of the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. J Neurosci. 1992;14:6500–6510. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06500.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yokota S, et al. Respiratory-related outputs of glutamatergic, hypercapnia-responsive parabrachial neurons in mice. J Comp Neurol. 2015;523:907–920. doi: 10.1002/cne.23720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Geerling JC. Kölliker-Fuse GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons project to distinct targets. J Comp Neurol. 2017;525:1844–1860. doi: 10.1002/cne.24164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mizusawa A, et al. Role of the parabrachial nucleus in ventilator responses of awake rats. J Physiol. 489:877–883. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Song G, et al. Hypoxia-excited neurons in the NTS send axonal projections to the Kölliker-Fuse/parabrachial complex in the dorsal pons. Neuroscience. 2011;175:145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.11.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lu YC, et al. Neurochemical properties of the synapses between the parabrachial nucleus-derived CGRP-positive axonal terminals and the GABAergic neurons in the lateral capsular division of central nucleus of amygdala. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;51:105–118. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8713-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sanz E, et al. Cell-type-specific isolation of ribosome-associated mRNA from complex tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13939–13944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907143106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Saper CB. House alarm. Cell Metab. 2016;23:754–755. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Russo AF. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP): a new target for migraine. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;55:533–552. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Huang ZJ, Zeng H. Genetic approaches to neural circuits in the mouse. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2013;36:183–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062012-170307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Madison L, et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci. 2010:13133–13140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Madisen L, et al. Transgenic mice for intersectional targeting of neural sensors and effectors with high specificity and performance. Neuron. 2015;85:942–958. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Gomez JL, et al. Chemogenetics revealed: DREADD occupancy and activation via converted clozapine. Science. 2017;357:503–507. doi: 10.1126/science.aan2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Rosenfeld MG, et al. Production of a novel neuropeptide encoded by the calcitonin gene via tissue-specific RNA processing. Nature. 1983;304:129–135. doi: 10.1038/304129a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Erickson JC, et al. Sensitivity to leptin and susceptibility to seizures of mice lacking neuropeptide Y. Nature. 1996;381:415–418. doi: 10.1038/381415a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kalra SP, et al. Interacting appetite-regulating pathways in the hypothalamic regulation of body weight. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:68–100. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.1.0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Palmiter RD, et al. Life without neuropeptide Y. Rec Prog Horm Res. 1998;53:163–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Qian S, et al. Neither agouti-related protein nor neuropeptide Y is critically required for the regulation of energy homeostasis in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5027–5035. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.14.5027-5035.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Tong Q, et al. Synaptic release of GABA by AgRP neurons is required for normal regulation of energy balance. Nat Neurosci. 11:998–1000. doi: 10.1038/nn.2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Krashes MJ, et al. Melanocortin-4 receptor-regulated energy homeostasis. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:206–219. doi: 10.1038/nn.4202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Krashes MJ, et al. Rapid, reversible activation of AgRP neurons drives feeding behavior in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1424–1428. doi: 10.1172/JCI46229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Wu Q, et al. Starvation after AgRP-neuron ablation is independent of melanocortin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2687–2692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712062105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]