Abstract

Despite advances over the past 20 years in colorectal cancer (CRC) screening, diagnosis, and treatment, survival outcomes remain suboptimal. Five-year survival for patients with locally advanced CRC is 69%; 5-year survival drops to 12% for patients with metastatic disease. Novel, effective systemic therapies are needed to improve long-term outcomes. In this review, we describe currently available systemic therapies for the treatment of locally advanced and metastatic CRC and discuss emerging therapies, including encouraging advances in identifying novel targeted agents and exciting responses to immunotherapeutic agents.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, emerging therapies, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, clinical trials

With nearly 135,000 new diagnoses and 49,000 deaths due to colorectal cancer (CRC) estimated in 2016, CRC is the third most common new cancer diagnosis and the third most common cause of cancer-related death for both men and women in the United States. 1 Since the 1980s, mortality rates for CRC have been declining in this country, 2 likely due to screening programs that detect pre-cancerous polyps and due to improvements in the diagnosis, surgical management, and systemic treatment of locally advanced and metastatic CRC. 3 4 5 While these trends are encouraging, survival outcomes with current treatment regimens remain suboptimal. Five-year survival for patients with locally advanced CRC is 69%; 5-year survival drops to 12% for patients with metastatic disease. 6 In addition to ongoing advances in curative-intent surgical approaches to metastatic disease and improvements in sequencing of multimodality treatment approaches, novel, effective systemic therapies are needed to improve long-term outcomes in CRC.

In this review, we first briefly describe the systemic therapies currently approved for treatment of locally advanced and metastatic CRC. We then discuss emerging systemic therapies and clinical trials available for patients with CRC. We discuss targeted and nontargeted agents, as well as immunotherapy approaches to CRC. We conclude with a discussion of future directions in the systemic treatment of CRC.

Currently Approved Therapies for Colorectal Cancer

Curative-Intent Adjuvant Therapy for Resected Colorectal Cancer

All systemic therapies currently approved for the treatment of CRC are shown in Table 1 . Since 1957, systemic therapy for colon cancer has been based on a fluorouracil backbone. 7 Fluorouracil predominantly inhibits thymidylate synthetase, causing DNA damage, but RNA damage probably also contributes to the therapeutic effect in CRC. 8 Adjuvant systemic therapy with fluorouracil increases the cure rate of resected locally advanced colon cancer when combined with levamisole, leucovorin, and most recently with oxaliplatin and leucovorin. 9 10 11 The 5-fluouracil (5-FU) pro-drug capecitabine is also approved as part of curative therapy for rectal cancer in combination with radiation therapy, and as part of monotherapy or combined with oxaliplatin for colon cancer. 12 13 In population-based registries, adherence to the NCCN guidelines for systemic adjuvant CRC treatment has been shown to correlate with improved survival for patients with high-risk Stage II and Stage III CRC. 14

Table 1. Systemic therapies approved for colorectal cancer through 2016.

| Therapy | Year approved | Therapeutic class | Component of curative therapy | Mechanism of action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorouracil (5FU) | 1958 | Cytotoxic | Yes | Interferes with synthesis of DNA and RNA |

| Floxuridine (FUDR) | 1970 | Cytotoxic | No | Metabolized to fluorouracil |

| Levamisole (with 5FU) | 1990 a | Cytotoxic | N/A | Not applicable |

| Leucovorin (with 5FU) | 1991 | Cytotoxic | Yes | Inhibits thymidylate synthetase |

| Irinotecan | 2000 | Cytotoxic | No | Inhibits DNA replication and transcription |

| Capecitabine | 2001 | Cytotoxic | Yes | Metabolized to fluorouracil |

| Oxaliplatin (with LV and 5FU) | 2002 | Cytotoxic | Yes | Inhibits DNA replication and transcription |

| Bevacizumab | 2004 | Antibody | No | Angiogenesis inhibitor (inhibits VEGF-A) |

| Cetuximab | 2004 | Antibody | No | Inhibits EGFR signaling |

| Panitumumab | 2006 | Antibody | No | Inhibits EGFR signaling |

| Aflibercept | 2012 | VEGFR 1–2 Ig fusion | No | Angiogenesis inhibitor (inhibits VEGF-A and VEGF-B) |

| Regorafenib | 2012 | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | No | Inhibits multiple tyrosine kinases, including VEGFR1-3 |

| Ramucirumab | 2014 b | Antibody | No | Angiogenesis inhibitor (inhibits VEGFR2) |

| Trifluridine/tipiracil | 2015 | Cytotoxic | No | Interferes with synthesis of DNA |

Withdrawn in 1999.

Approved for colon cancer in 2015.

Systemic Therapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

Only two cytotoxic drugs (oxaliplatin and fluorouracil), one pro-drug (capecitabine), and one drug modulator (leucovorin) are able to add to the cure rate of resected CRC. For patients with incurable metastatic CRC, angiogenesis inhibitors, epidermal growth factor inhibitors, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and a novel cytotoxic drug all can add to overall survival.

Angiogenesis Inhibitors

Formation of new blood vessels is a fundamental event in tumor growth and metastasis. The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family of proteins and receptors play a crucial role in angiogenesis. 15 Bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody against VEGF, significantly improves overall survival when added to fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy with either oxaliplatin or irinotecan 16 17 18 and is approved for use in the first-line treatment of metastatic CRC. Bevacizumab has also shown a modest but significant improvement in overall survival (1.4 months) when continued beyond disease progression on first-line therapy and incorporated into the second-line regimen. 19 Ziv-aflibercept is a recombinant fusion protein that binds VEGF-A and VEGF-B. It is approved for second-line treatment of metastatic CRC in combination with FOLFIRI in patients who have previously experienced disease progression on an oxaliplatin-based regimen, based on a 1.4-month overall survival benefit. 20 Ramucirumab is a monoclonal antibody against VEGFR2. It is approved in combination with FOLFIRI for second-line treatment of metastatic CRC in patients who have previously progressed on FOLFOX plus bevacizumab, based on a 1.6-month overall survival benefit. 21 Because of concerns about toxicities and cost in the face of modest benefit, as well as unanswered questions about the effective sequencing of antiangiogenic agents, it is unclear whether ziv-aflibercept or ramucirumab will become commonly used therapies for metastatic CRC.

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibition

Inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway has also proven useful in the treatment of CRC. Only CRCs that are KRAS and NRAS wild type respond to the EGFR antibodies cetuximab and panitumumab. 22 23 Among patients with metastatic CRC, the optimal sequencing of EGFR and antiangiogenic agents remains to be determined. In the Phase III U.S. Intergroup study of FOLFOX or FOLFIRI plus either bevacizumab or cetuximab among patients with KRAS wild type, untreated, metastatic CRC, median survival was the same (29 months) regardless of whether patients received bevacizumab or cetuximab. 24 However, a separate Phase III trial (FIRE-3) of first-line FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFOX plus bevacizumab demonstrated a slight overall survival advantage for first-line FOLFIRI plus cetuximab (28.7 vs. 25 months). 25 The controversial New EPOC study performed in the United Kingdom revealed that the addition of cetuximab to chemotherapy in CRC patients before and after a planned curative-intent resection of liver metastases resulted in worse overall survival, with a median survival of 14 months for the cetuximab plus chemotherapy arm and 20 months for the chemotherapy-only arm. 26 However, conclusions from this study have been called into question for many reasons, including concerns regarding variations in the quality of surgery for resection of liver metastases and inappropriate patient selection and randomization, 27 as well as concerns about the appropriateness of progression-free survival as the study's primary endpoint. 28 Among patients with Stage III CRC, the addition of EGFR antibody therapy to adjuvant FOLFOX chemotherapy did not provide a survival benefit 29 and cetuximab is not used in the adjuvant treatment of locally advanced CRC.

Oral Multitargeted Therapies

Regorafenib is an orally administered multi-kinase inhibitor that has been approved for treatment of metastatic CRC that has progressed through first- and second-line systemic therapies with 5-FU, oxaliplatin, irinotecan, a VEGF inhibitor, and, if appropriate, an EGFR antibody. The initial phase II study of regorafenib demonstrated a 74% disease control rate, with 4% partial response rate and 70% stable disease rate. However, the median number of days on treatment was only 49. 30 An international, placebo-controlled phase III study demonstrated an improved survival of 6.4 months for the regorafenib arm compared with 5 months for the placebo arm. 31 However, the complete and partial response rate was less than 1%. Among patients in the regorafenib arm, 41% had disease stabilization compared with 15% of patients in the placebo arm. In practice, regorafenib is not well tolerated by many patients and we have not seen widespread adoption of its use in palliative therapy of advanced CRC. It also seems unlikely that regorafenib will prove beneficial in curative-intent therapy for earlier stage disease.

Trifluridine is a nucleic acid analog that, when given with the degradation inhibitor tipiracil hydrochloride, demonstrated antitumor activity in cell lines resistant to 5-FU. 32 Trifluridine/tipiracil (TAS-102) was compared with placebo in patients with refractory metastatic CRC and improved median survival from 5.3 to 7.1 months. 33 Objective response rates were very low (1.6% in the trifluridine/tipiracil arm as compared with 0.4% in the placebo arm), but disease stabilization rates were significantly higher in the trifluridine/tipiracil arm (44%) compared with the placebo arm (16%). Similar to analyses of regorafenib, at the 4-month analysis, progression-free survival was 25% for patients in the trifluridine/tipiracil arm compared with 5% for patients in the placebo arm, indicating that the trifluridine/tipiracil offered a measure of disease control.

Novel Systemic Therapies for Colorectal Cancer

A selected listing of currently ongoing clinical trials of novel systemic therapies in the treatment of CRC is shown in Table 2 and described in more detail later. There are more than 10 genetic phenotypes that make up adenocarcinoma of the colon. In-depth genetic and proteomic characterization of 267 CRCs demonstrated that 15% had a hypermutated phenotype, while among the non-hypermutated tumors, mutations in APC (81%), TP53 (60%), and KRAS (43%) were the most common. 34 However, development of therapies directed at these common mutations has proven challenging, and most clinical trials in 2016 are directed at novel therapeutic targets. In lung cancer, identification of the critical role of EGFR mutations has led to the approval of erlotinib, a small oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor, as a more effective and less toxic systemic therapy for the treatment of metastatic lung cancer. 35 This example drives the search for finding and interrupting key signaling pathways in metastatic CRC. 34

Table 2. Selected ongoing clinical trials of novel targeted agents in colorectal cancer.

| Compound | Therapeutic class | Targeted pathway | Phase | Trial location(s) | Registration date | NCT tracker |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrectinib | Small molecule | NTRK1/2/3, ROS1, ALK | I/II | United States, over 20 sites | October 2015 | NCT02568267 |

| LOXO-101 | Small molecule | TRK1, 2, 3 | I | United States, three sites | October 2015 | NCT02576431 |

| BBI608 (napabucasin) | Small molecule | Cancer stem cell pathways, Stat3 | I, with FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab | Japan | December 2015 | NCT02641873 |

| PRI-724 | Small molecule | Wnt; CBP/beta-catenin | II, with FOLFOX plus bevacizumab | April 2015 | NCT02413853 | |

| Foxy-5 | Peptide | Wnt 5a mimic, to impair tumor cell migration | I | Denmark | January 2016 | NCT02655952 |

| Selinexor | Small molecule | Selective inhibitor of nuclear transport | I, with FOLFOX | Europe, two sites | August 2015 | NCT02384850 |

| BAX69 (imalumab) | Antibody | MIF inhibitor | II, combined with various chemotherapies | United States, over 10 sites | May 2015 | NCT02448810 |

| PD-0325901 | Small molecule | MEK | I, with crizotinib | United Kingdom | June 2015 | NCT02510001 |

| Selumetinib | Small molecule | MEK | I/II, with afatinib | The Netherlands, three sites | November 2014 | NCT02450656 |

| Selumetinib | Small molecule | MEK | I, with cyclosporine | United States, over seven sites | July 2014 | NCT02188264 |

| MEK162 (binimetinib) | Small molecule | MEK | I, with FOLFOX | California | January 2014 | NCT02041481 |

| BGJ398 (infigratinib) | Small molecule | FGFR kinase | I/II, with FOLFOXIRI | New York | October 2015 | NCT02575508 |

| Nintedanib | Small molecule | VEGFR; FGFR, PDGFR | I/II, with capecitabine | New York and California | March 2015 | NCT02393755 |

| Anlotinib | Small molecule | VEGFR2, VEGFR3 | III | China, over 20 sites | December 2014 | NCT02332499 |

| CPI-613 | Small molecule | Mitochondrial "poison" | I, with 5FU | North Carolina | September 2014 | NCT02232152 |

| PF-03446962 | Antibody | TGFβ receptor ALK1 | I, with regorafenib | North Carolina | April 2014 | NCT02116894 |

| Sym004 | Antibody | EGFR antibody mixture | II | United States and Europe, over 70 sites | March 2014 | NCT02083653 |

| MGN1703 | Nucleic acid | TLR-9 agonist | III | Europe over 100 sites | February 2014 | NCT02077868 |

| Cabozantinib | Small molecule | c-MET, VEGFR2 | I/II, with panitumumab | North Carolina | December 2013 | NCT02008383 |

| Genistein | Small molecule | Wnt-1 | I/II, with FOLFOX or FOLFOX plus bevacizumab | New York. | November 2013 | NCT01985763 |

Targeted Therapy

HER2/Neu-Directed Therapy

About 10% of colon tumors have amplifications of erb-2 , suggesting that blockade of the HER2/neu pathway may prove of therapeutic benefit in some patients with metastatic CRC. While HER2/neu amplification is rare in CRC, the HER2/neu-amplified tumors tend to be more aggressive. 36 A phase II trial of dual HER2/neu-directed therapy with trastuzumab and lapatinib demonstrated an overall response rate of 35%, with a median time to progression of 5.5 months. 37

NTRK-Directed Therapy

Entrectinib is a potent small molecule inhibitor of the tyrosine kinases trkA (encoded by NTRK1 ), trkB (encoded by NTRK-2 ), trkC (encoded by NTRK-3 ), ALK, and ROS1. In preclinical models, treatment with entrectinib leads to apoptosis and downstream signaling effects on the tumor cells. 38 In the initial phase I study of various tumor types that contained amplification of the oncogenes, 10 responses were observed in the 11 patients treated at the recommended phase I dose, with durable responses lasting up to 16 months. 39 Loxo-101 is a TRK inhibitor that has demonstrated activity in preclinical models in tumors with TRK 1, 2, and 3 mutations. 40 A phase I study of this agent is ongoing (NCT02576431).

Exportin-1-Directed Therapy

Exportin-1 is a protein that mediates the nuclear export of over 200 cargo proteins, including many transcription factors important in the cancer phenotype. 41 Selinexor is an orally available, selective inhibitor of exportin-1 that has previously been tested in a phase I study. 42 Treatment with selinexor was associated with stable disease in 44% of CRC tumors with KRAS mutations. 43 It is currently being tested in a phase I trial with FOLFOX (NCT02384850).

Chemokine Inhibition

Macrophage migratory inhibitory factor (MIF) is a chemokine that is involved in many pathways of innate immunity. MIF overcomes the immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids, and can activate ERK1/ERK2 signaling. 44 45 Treatment with anti-MIF antibodies has demonstrated slowed tumor growth in a prostate cancer xenograft model. 46 Imalumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody specific for oxidized MIF. 47 Imalumab has been tested in a phase I study. A maximum tolerated dose was not reached and nine patients (32%) had stable disease at the end of 2 months. 48 A phase II study of imalumab in CRC, in combination with either panitumumab or 5FU/leucovorin, is ongoing (NCT02448810).

Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase (MAP2K1, Also Known as MEK)

The mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases MEK1 and MEK2 are of considerable interest in colon cancer. 49 The majority of the clinical trials currently recruiting patients are using MEK inhibition in combination with other systemic therapies ( Table 2 ). A phase I study of the MEK inhibitor binimetinib (MK162) in combination with FOLFOX chemotherapy has been conducted. In that study, 16 patients with metastatic colon cancer were treated. Ten patients had stable disease at 2 months, with five of those having stable disease for 5 months. 50 No dose-limiting toxicities were encountered. A phase I trial of binimetinib in combination with FOLRIRI has been registered (NCT02613650) and is planned at the University of Utah.

A phase I trial of the MEK inhibitor PD-0325901 in combination with crizotinib, being used as a MET inhibitor, the “MEK and MET Inhibition in Colorectal Cancer (MErCuRIC1),” is ongoing at the University of Oxford (NCT02510001). A phase I/II study of the MEK inhibitor, selumetinib, in combination with the orally available EGFR inhibitor, afatanib, is planned for the Netherlands (NCT02450656). For this study, patients are required to have a KRAS (exon 2, 3 or 4) mutation and wild-type PIK3CA (defined as absence of mutations in exons 9 and 20). Preclinical results have demonstrated promising activity of inhibiting the MEK pathway with selumetinib and the Wnt pathway with cyclosporin A. 51 Based on these results, a phase I expansion cohort of the MEK inhibitor selumetinib in combination with cyclosporine is being conducted at nine locations in North America (NCT02188264).

FGFR and MET Inhibition

Preclinical research studies have shown that BGJ398 selectively suppresses fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) signaling and proliferation in cancer cells with FGFR dependency. Blockade of FGFR can also lead to decreased angiogenesis. 52 In addition, BGJ398 blocks bFGF-induced angiogenesis in endothelial cell lines. A phase I/II study is planned at Roswell Park, combining FGFR with FOLFOX (NCT02575508).

The MET/hepatocyte growth factor pathway is important in thyroid cancer, lung cancer, colon cancer, and several other malignancies. 53 Constitutive activation of the MET oncogene pathway has been demonstrated in CRC, and has been associated with resistance to EGFR-based therapies. 54 cabozantinib is a small molecule MET inhibitor that is approved for use in advanced medullary thyroid cancer. 55 Cabozantinib is being tested in metastatic colon cancer, alone and in combination with panitumumab (NCT02008383).

Angiogenesis and EGFR Inhibitors in Clinical Trials

Nintedanib is an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor with activity against the VEGFR, FGFR, and PGFR pathways. 56 Nintedanib in combination with FOLFOX has been studied in a phase I/II clinical trial. 57 The study randomized 128 patients in a 2:1 randomization of FOLFOX plus nintedanib compared with FOLFOX plus bevacizumab. The FOLFOX plus nintedanib arm had 62% progression-free survival at 9 months, versus 70% in the FOLFOX plus bevacizumab arm. A phase I/II trial of capecitabine with nintedanib has been registered (NCT02393755), and will have the advantage of being an all-oral regimen.

Anlotinib is an orally available tyrosine kinase inhibitor, primarily of the VEGF pathway. It has been tested in a phase I study, resulting in stable disease in one patient. 38 A phase III trial of this agent has been registered (NCT02332499).

PF-03446962 is a humanized monoclonal antibody directed at activin receptor kinase 1 (ALK-1). ALK-1 is involved in new blood vessel formation; therefore, inhibition of this pathway is being studied to inhibit tumor-induced angiogenesis. 58 PF-03446962 has been tested in patients with hepatocellular cancer with no objective responses, though some patients achieved stable disease. 59 It has been tested in refractory urothelial carcinoma with disappointing results. 60

Antibody-mediated blockade of the EGFR pathway is of clinical benefit in metastatic CRC. Sym004 is a mixture of two EGFR antibodies that target non-overlapping EGFR epitopes. The antibody combination induces rapid elimination of the EGFR receptor from the cell surface. 61 In a phase I trial of Sym004 in patients with refractory CRC, the combination had a clinical benefit in 17 of 39 (44%) patients with 13% achieving a partial response. 62 A phase II study of Sym004 versus a control arm has been registered (NCT02083653).

TRL-9 and Toll-Like Receptor 8

MGN1703, a subcutaneously administered TLR-9 agonist, is being studied as maintenance therapy for metastatic CRC (NCT02077868). A previous randomized phase II study in CRC patients demonstrated an improved progression-free survival for the patients treated with MGN1703, with a hazard ratio of 0.55. 63

Motolimod (VTX-2337) is a small-molecule agonist of toll-like receptor 8 that can directly activate dendritic cells, monocytes, and natural killer cells. 64 It is being tested for therapeutic efficacy alone or with a priming dose of cyclophosphamide (NCT02650635). Preliminarily, it was found to augment tumoricidal natural killer activity when administered to patients with head and neck cancer. 65

Agents without Molecularly Defined Targets

CPI-613 is an intravenous therapy that causes death of cancer cells but not of normal cells. 66 In a study of patients with hematologic malignancies, it resulted in a response in 4 out of 21 patients. 67 It has a dose-limiting toxicity of renal failure. A phase I trial in combination with 5FU in CRC patients is ongoing.

Genistein is a soy-derived phytoestrogen that has been investigated in cancer for its proapoptotic and antiproliferative properties. 68 Typical dietary intake of naturally occurring phytoestrogens ranges from 5 mg/day in Western Countries up to 200 mg/day in Asia. 69 Genistein has demonstrated synergy with 5FU in causing apoptosis of chemotherapy-resistant colon cancer cell lines. 70 It is being tested in a phase I study in combination with FOLFOX with or without bevacizumab.

Immunotherapy Approaches to Colorectal Cancer

Interest in immunotherapy as an approach to cancer treatment has grown substantially in recent years. In CRC, as in other solid tumors, treatments that maintain efficacy when standard chemotherapies have failed are desirable. Furthermore, treatments that selectively target cancer-dependent pathways and avoid the toxicities that result from chemotherapy's cytotoxic effect on healthy tissues stand to improve both objective responses to cancer treatment and patient tolerance of the treatment regimen. Immunotherapy approaches are designed to trigger the immune system to respond to tumor-specific antigens and attack and destroy tumor cells, ideally with minimal effect on normal tissues. Thus, many investigators and clinicians hope that immunotherapy will prove to be an effective strategy in the treatment of CRC.

Immune Checkpoint Inhibition and Modulation

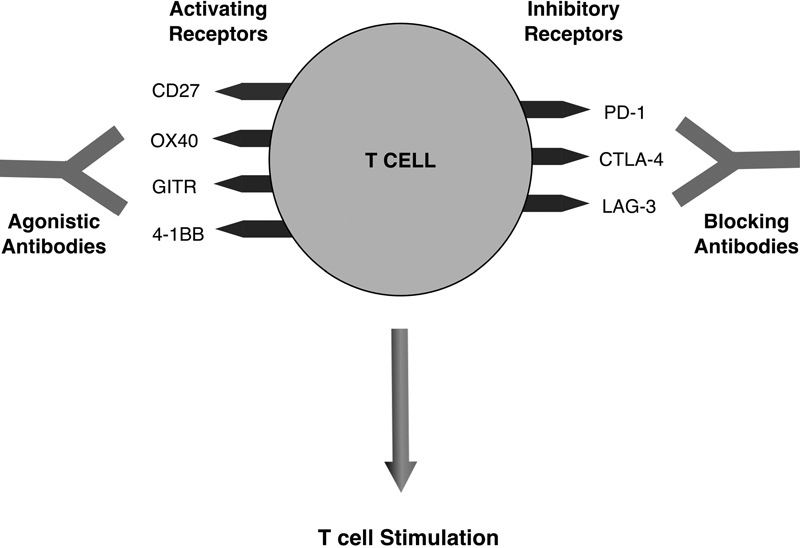

Immune checkpoint modulation has been one of the most clinically promising immunotherapy treatment approaches to solid tumors to date. This approach to therapy depends on blocking those T cell receptors that inhibit T cell activity or upregulating those receptors that activate T cell activity ( Fig. 1 ). Inhibition of the PD-1/PD-L1 axis has produced exciting results in melanoma, 71 NSCLC, 72 and other solid tumors. Tumors with upregulation of the immune checkpoint proteins PD-1 and PD-L1 induce T cell anergy, thus allowing the cancer cells to survive. 73 Inhibition of these proteins using anti-PD-1 antibodies or anti-PD-L1 antibodies allows for T cell activation and has produced durable responses among patients with refractory solid tumors. 74 75 76 However, use of this therapy in CRC has so far shown promising results only among those patients with deficient mismatch repair (MMR).

Fig. 1.

T cell targets for immune checkpoint inhibition and modulation. T cell stimulation is enhanced by antibodies that block inhibitory receptors or upregulate activating receptors. (Adapted from Mellman et al; Nature 2011;480:480–489.)

Approximately 15% of patients with CRC (including ∼4% of patients with advanced stage disease) have deficient MMR, either as a result of genetic inheritance of an inactive allele of one of the MMR genes (2.5% of patients) or sporadic inactivation of MMR genes (12.5% of patients). 73 Patients with deficient MMR accumulate a large number of mutations, particularly in regions of repetitive DNA sequences, resulting in microsatellite instability (MSI). It is hypothesized that these tumors incite a stronger T cell response because they carry more neoantigens and thus look more “foreign” to the native immune system. 77 Therefore, CRC patients with deficient DNA MMR may be particularly good candidates for checkpoint blockade therapy. 78

A phase II study of PD-1 blockade with the anti-PD-1 antibody, pembrolizumab, in patients with stage IV CRC and non-CRC refractory to multiple previous lines of therapy reported an immune-mediated response rate of 40% in patients with MMR-deficient CRC, versus 0% in patients with MMR-proficient CRC. Immune-related progression-free survival was 78% among patients with MMR-deficient CRC versus 11% among patients with MMR-proficient CRC. Neither median progression-free nor median overall survival rates were reached in the MMR-deficient cohort. Whole-exome sequencing revealed a mean of 1,782 somatic mutations in MMR-deficient tumors versus 73 in MMR-proficient tumors ( p = 0.007), and high loads of somatic mutations were associated with prolonged progression-free survival ( p = 0.02). 79 Though this was a small trial and included only 11 patients with MMR-deficient CRC, the results are promising and several additional studies of anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 antibody treatments are ongoing. Keynote-164 (NCT02460198) is a large, phase II trial currently enrolling patients to assess the benefit of pembrolizumab for unresectable or metastatic MMR-deficient CRC that has been refractory to two or more previous lines of therapy. A selected listing of currently ongoing clinical trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors and modulators in the treatment of CRC is shown in Table 3 , and described in more detail later.

Table 3. Selected ongoing clinical trials of immune checkpoint inhibition and modulation in colorectal cancer.

| Target | Compound | NCT tracker | Phase | Tumor type | Additional target(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD-1 | Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) | NCT01876511 | II | Advanced CRC; MSI-high noncolorectal cancer | |

| NCT02179918 | I | Advanced solid tumors | Anti-4-1BB (PF-05082566) | ||

| NCT02460198 | II | Advanced, MMR-deficient or MSI-high CRC | |||

| NCT02298959 | I | Advanced solid tumors | Anti-4-1BB (PF-05082566) | ||

| Nivolumab | NCT02060188 | I/II | Advanced CRC | Anti-CTLA-4 (ipilimumab) | |

| AMP-514 (MEDI0680) | NCT02118337 | I | Advanced solid tumors | Anti-PD-L1 (durvalumab) | |

| PD-L1 | Durvalumab (MEDI4736) | NCT01693562 | I/II | Advanced solid tumors | |

| NCT02484404 | I/II | Advanced solid tumors | PARP inhibitor (olaparib; cediranib) | ||

| NCT02227667 | II | Advanced CRC with MSI-H or increased tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes | |||

| Atezolizumab (MPDL3280A) | NCT01375842 | I | Advanced solid tumors or hematologic malignancies | ||

| NCT01633970 | I | Advanced solid tumors, including advanced CRC and MSI-H CRC | Bevacizumab; FOLFOX + bevacizumab; carboplatin + paclitaxel; carboplatin + pemetrexed; carboplatin + nab-paclitaxel; nab-paclitaxel | ||

| NCT02655822 | I | Advanced solid tumors | Small molecule targeting the adenosine-A2A receptor (CPI-444) | ||

| Avelumab (MSB0010718C) | NCT01772004 | I | Advanced solid tumors | ||

| CTLA-4 | Ipilimumab | NCT02239900 | I/II | Advanced solid tumors with lung or liver metastases | Stereotactic body radiation therapy |

| Tremelimumab | NCT01975831 | I | Advanced solid tumors | Anti-PD-L1 (durvalumab) | |

| NCT02261220 | I | Advanced solid tumors | Anti-PD-L1 (durvalumab) | ||

| LAG-3 | BMS-986016 | NCT01968109 | I | Advanced solid tumors | Anti-PD-1 (nivolumab) |

| CD27 | Varlilumab (CDX-1127) | NCT01460134 | I | Advanced solid tumors and advanced hematologic malignancies | |

| NCT02335918 | I/II | Advanced solid tumors | Anti-PD-1 (nivolumab) | ||

| OX40 | MEDI6469 | NCT02205333 | I/II | Advanced solid tumors; diffuse large B cell lymphoma | Anti-CTLA-4 (tremelimumab) or anti-PD-L1 (durvalumab) |

| MEDI6383 | NCT02221960 | I | Advanced solid tumors | ||

| MOXR0916 | NCT02219724 | I | Advanced solid tumors | ||

| GITR | TRX518 | NCT01239134 | I | Advanced solid tumors | |

| MK-4166 | NCT02132754 | I | Advanced solid tumors | Anti-PD-1 (pembrolizumab) | |

| AMG-228 | NCT02437916 | I | Advanced solid tumors | ||

| 4-1BB | Urelumab | NCT02253992 | I/II | Advanced solid tumors; advanced B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | Anti-PD-1 (nivolumab) |

| BMS-663513 | NCT01471210 | I | Advanced solid tumors; advanced B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | ||

| NCT02110082 | I | Advanced CRC or head and neck cancer | Cetuximab | ||

| KIR | Lirilumab | NCT01714739 | I | Advanced solid tumors | Anti-PD-1 (nivolumab) |

CTLA-4 represents another potential target for checkpoint inhibition in CRC. CTLA-4 is a T cell surface protein that, when bound by B7 protein on activated antigen presenting cells, inhibits T cell activation and induces T cell anergy. 80 Tremelimumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody against CTLA-4, was tested as single-agent therapy in a phase II trial of 47 patients with refractory metastatic CRC. The agent did not show significant activity in this study, although one patient had a partial response with a time from enrollment to disease progression of 14.5 months. 81 The MMR status of the patients was not reported in this study. Perhaps these agents will show activity in patients with MMR-deficient CRC, or in combination with other immunomodulatory agents. There are currently several ongoing trials of the CTLA-4 inhibitors, tremelimumab and ipilimumab, alone or in combination with other immune checkpoint inhibitors, in the treatment of patients with advanced solid tumors including CRC.

Like PD-1, LAG-3 is a negative regulator expressed during T cell activation. High-level, dual expression of LAG-3/PD-1 has been shown on tumor-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ cells in transplantable tumors in mice models. 82 Thus, inhibition of LAG-3 or combined LAG-3/PD-1 inhibition may promote antitumor immune responses. Clinical trials of an anti-LAG-3 antibody (BMS-986016), alone or in combination with the anti-PD-1 antibody, nivolumab, are currently ongoing in patients with solid tumors, including CRC.

Other potential targets for immune checkpoint modulation in CRC include members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily. These are costimulatory molecules that promote T cell activation. CD27 is one such molecule and plays a role in T cell survival, T cell activation, and the cytotoxic activity of natural killer cells. 83 Clinical trials of the CD27 agonist antibody varlilumab, alone or in combination with nivolumab, are ongoing. OX40 is another costimulatory molecule in this family. High levels of OX40 expression in tumor lymphocytes have been correlated with improved survival among CRC patients. 84 Studies of OX40 agonist antibodies (MEDI6469, MEDI6383, MOXR0916), alone or in combination with other immune checkpoint inhibitors, are ongoing. GITR is a surface receptor molecule involved in inhibiting the suppressive activity of regulatory T lymphocytes and extending the survival of T effector cells. 78 Large numbers of tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells with high expression of GITR have been found in the liver metastases of CRC patients. 85 Agonistic GITR antibodies (TRX518, MK-4166, AMG-228) are being studied in clinical trials, alone or in combination with anti-PD-1 antibodies. 4–1BB is a T cell costimulatory receptor that is induced after T cell antigen recognition. 86 Two agonistic antibodies to 4–1BB, urelumab and BMS-663513, are currently being tested in phase I trials enrolling patients with CRC. These agents are being tested alone and also in combination with an anti-PD-1 antibody (nivolumab) and an EGFR antibody (cetuximab).

One additional target for immune checkpoint modulation in CRC, KIR, is a receptor expressed on natural killer cells that binds HLA class I molecules on target cells, thus delivering an inhibitory signal that prevents natural kill-cell–mediated cytotoxicity. 87 An anti-KIR antibody, lirilumab, is currently being tested in combination with nivolumab in a phase I trial in patients with advanced solid tumors, including CRC.

While promising, immune checkpoint inhibition and modulation does not yet play a role in the standard treatment of patients with CRC. It seems likely that inhibition of the PD-1/PD-L1 axis will become standard therapy for patients with metastatic, MMR-deficient (MSI-high) CRC, though additional prospective studies are needed to confirm the benefits seen in early studies in this patient cohort. Whether immune checkpoint inhibition or modulation will show clinical efficacy in patients with MMR-proficient CRC, as first-line therapy of metastatic disease, or in earlier stage disease, remains to be seen.

Adoptive Cell Therapy

Adoptive cell therapies using autologous T cells that have been genetically engineered to express high-affinity receptors for tumor-associated antigens have produced exciting responses in melanoma. 88 89 90 This treatment approach has also been tested in CRC patients. In a phase I clinical trial, three patients with metastatic CRC were treated with autologous T lymphocytes genetically engineered to express a murine T cell receptor against human carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). All three patients had significant decreases in their serum CEA levels and one patient had objective regression of metastases in the lungs and liver. These responses were transient, however, with eventual disease progression. Furthermore, all three patients developed severe, transient inflammatory colitis leading to cessation of the trial. 91

Clinical trials of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified T cells have led to dramatic and sustained responses in hematologic malignancies. 92 93 Some of the first phase I clinical trials using CAR T cells were done in patients with metastatic CRC. The treatment was well tolerated, but no objective responses were observed. 94 A later study of second-generation CAR T cells targeting ERBB2 in a patient with metastatic CRC resulted in almost immediate development of respiratory distress, cytokine storm, and, unfortunately, the patient's death. 95 The cause of death was thought to be T cell reaction to the normal, low-level expression of ERBB2 in healthy lung tissue. This case and others highlight the potential for extreme toxicity with adoptive cell therapies, and subsequent research has focused on strategies to increase the safety of adoptive cell therapy. 96

Attempts to successfully incorporate adoptive cell therapies in the treatment of solid tumors, including CRC, are ongoing. 97 A phase I study of cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for the tumor-associated antigens NY-ESO-1, MAGEA4, PRAME, survivin, and SSX (NCT02239861) and a separate phase I study of NY-ESO-1–specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (NCT01967823) are currently enrolling patients with advanced solid tumors, including CRC. Two phase I/II studies of CAR T cells, one specific for VEGFR2 (NCT01218867) and one specific for EGFR, are enrolling metastatic CRC patients. The National Cancer Institute is currently recruiting patients with advanced solid and hematologic malignancies, including CRC, to a phase I study of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, which are infused following a non-myeloablative lymphocyte depleting preparative regimen of cyclophosphamide and fludarabine (NCT01174121).

Vaccine Therapy

Cancer vaccines are designed to elicit an immune response against tumor-specific or tumor-associated antigens. They have been developed and tested in clinical trials using either autologous CRC tumor cells or autologous dendritic cells as the vaccine vector. A multicenter, prospective, randomized phase III trial of adjuvant BCG plus irradiated autologous tumor cells (OncoVax) in patients with surgically resected stage II and III colon cancers showed a statistically significant improvement in recurrence-free survival (37.7 vs. 21.3%, p = 0.009) for patients with stage II disease who received the vaccine. 98 There were no significant benefits for patients with stage III disease. Based on these results, a phase IIIB study of OncoVax in patients with resected, stage II colon cancer is currently ongoing (NCT02448173). For patients with surgically resected stage III CRC who have completed adjuvant chemotherapy (colon primary) or chemotherapy and radiation (rectal primary), a phase I study of AVX701, a vaccine that consists of an alphavirus replicon encoding CEA, is ongoing (NCT01890213). For patients with metastatic CRC, two phase I trials using GVAX are currently enrolling. GVAX is an autologous CRC tumor cell–derived vaccine that has been engineered to express granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. One trial is enrolling patients with surgically resectable liver metastases from CRC (NCT01952730) and the other combines GVAX with cyclophosphamide and SGI-110 (guadecitabine), a small molecule, next-generation DNA hypomethylating agent (NCT01966289). For patients with metastatic CRC that expresses HER2/neu, two separate phase I trials of anti-HER2/neu vaccines are ongoing (NCT01376505; NCT01730118).

Oncolytic Viruses

Oncolytic viral therapy uses viruses that are genetically modified to selectively replicate inside cancer cells and induce cancer cell death, subsequently stimulating an immune response against other cancer cells. Reolysin is a reovirus serotype, double-stranded replication-competent RNA non-enveloped icosahedral virus. It induces cytopathic and anticancer effects in cells with an activated ras pathway due to inhibition of the double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase. A phase I study of Reolysin administered to 18 patients with advanced solid tumors, including four patients with CRC, showed the vaccine to be well-tolerated and 1 patient with breast cancer experienced a partial tumor response. 99 For patients with FOLFIRI-naïve, KRAS -mutated metastatic CRC, there is an ongoing phase I trial of Reolysin given in combination with FOLFIRI and bevacizumab (NCT01274624).

Conclusion

Though recent advances in systemic therapy for CRC have been encouraging, continued research is needed to improve patient outcomes. While there are currently no obvious candidates for novel additions to curative-intent adjuvant systemic therapy for resected locally advanced CRC, the results of a recently completed phase III clinical trial of 3 versus 6 months of adjuvant FOLFOX or XELOX for resected stage II or stage III CRC may affect the recommended duration of adjuvant therapy.

Further research to better understand the genetic drivers of CRC may lead to novel targeted agents or combinations of targeted agents to inhibit multiple genes. Additionally, understanding how to drive the immune system in a more specific manner may increase the efficacy and reduce the toxicities of immunotherapy approaches to CRC, and hopefully provide benefits that extend to all CRC patients. Regimens that combine immune therapies or small molecule-targeted agents with conventional chemotherapies to target several different pathways, coupled with further research into the optimal sequencing of these therapies, may lead to sustained responses and improved outcomes. Systemic therapies for advanced CRC that improve response rates and allow for successful surgical resection of metastatic disease could potentially improve overall survival and even increase cure rates for a substantial number of patients.

References

- 1.Siegel R L, Miller K D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(01):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society.Cancer Facts & Figures 2016Atlanta: American Cancer Society;2016. Available at:http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2016/. Accessed March 18, 2016

- 3.Haggar F A, Boushey R P. Colorectal cancer epidemiology: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22(04):191–197. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1242458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopetz S, Chang G J, Overman M J et al. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(22):3677–3683. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.André T, Boni C, Navarro M et al. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(19):3109–3116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(04):220–241. doi: 10.3322/caac.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heidelberger C, Chaudhuri N K, Danneberg Pet al. Fluorinated pyrimidines, a new class of tumour-inhibitory compounds Nature 1957179(4561):663–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Longley D B, Harkin D P, Johnston P G. 5-fluorouracil: mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(05):330–338. doi: 10.1038/nrc1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moertel C G, Fleming T R, Macdonald J S et al. Intergroup study of fluorouracil plus levamisole as adjuvant therapy for stage II/Dukes' B2 colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(12):2936–2943. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.12.2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolmark N, Rockette H, Mamounas E et al. Clinical trial to assess the relative efficacy of fluorouracil and leucovorin, fluorouracil and levamisole, and fluorouracil, leucovorin, and levamisole in patients with Dukes' B and C carcinoma of the colon: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project C-04. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(11):3553–3559. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.11.3553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.André T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(23):2343–2351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Connell M J, Colangelo L H, Beart R W et al. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin in the preoperative multimodality treatment of rectal cancer: surgical end points from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project trial R-04. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(18):1927–1934. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.7753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Twelves C, Scheithauer W, McKendrick J et al. Capecitabine versus 5-fluorouracil/folinic acid as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer: final results from the X-ACT trial with analysis by age and preliminary evidence of a pharmacodynamic marker of efficacy. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(05):1190–1197. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boland G M, Chang G J, Haynes A B et al. Association between adherence to National Comprehensive Cancer Network treatment guidelines and improved survival in patients with colon cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(08):1593–1601. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hicklin D J, Ellis L M. Role of the vascular endothelial growth factor pathway in tumor growth and angiogenesis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(05):1011–1027. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(23):2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao Y, Tan A, Gao F, Liu L, Liao C, Mo Z. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing chemotherapy plus bevacizumab with chemotherapy alone in metastatic colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24(06):677–685. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0655-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner A D, Arnold D, Grothey A A, Haerting J, Unverzagt S. Anti-angiogenic therapies for metastatic colorectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(03):CD005392. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005392.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennouna J, Sastre J, Arnold D et al. Continuation of bevacizumab after first progression in metastatic colorectal cancer (ML18147): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(01):29–37. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70477-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Cutsem E, Tabernero J, Lakomy R et al. Addition of aflibercept to fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan improves survival in a phase III randomized trial in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer previously treated with an oxaliplatin-based regimen. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(28):3499–3506. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.8201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tabernero J, Yoshino T, Cohn A L et al. Ramucirumab versus placebo in combination with second-line FOLFIRI in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma that progressed during or after first-line therapy with bevacizumab, oxaliplatin, and a fluoropyrimidine (RAISE): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(05):499–508. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karapetis C S, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker D J et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(17):1757–1765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amado R G, Wolf M, Peeters M et al. Wild-type KRAS is required for panitumumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(10):1626–1634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.7116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venook A P, Niedzwiecki D, Lenz H-Jet al. CALGB/SWOG 80405: Phase III trial of irinotecan/5-FU/leucovorin (FOLFIRI) or oxaliplatin/5-FU/leucovorin (mFOLFOX6) with bevacizumab (BV) or cetuximab (CET) for patients (pts) with KRAS wild-type (wt) untreated metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum (MCRC)J Clin Oncol2014;32(15, Suppl):Abstract LBA3

- 25.Heinemann V, von Weikersthal L F, Decker T et al. FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE-3): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(10):1065–1075. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70330-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Primrose J, Falk S, Finch-Jones M et al. Systemic chemotherapy with or without cetuximab in patients with resectable colorectal liver metastasis: the New EPOC randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(06):601–611. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nordlinger B, Poston G J, Goldberg R M. Should the results of the new EPOC trial change practice in the management of patients with resectable metastatic colorectal cancer confined to the liver? J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(03):241–243. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasegawa K, Oba M, Kokudo N. Cetuximab for resectable colorectal liver metastasis: new EPOC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(08):e305–e306. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alberts S R, Sargent D J, Nair S et al. Effect of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin with or without cetuximab on survival among patients with resected stage III colon cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307(13):1383–1393. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strumberg D, Scheulen M E, Schultheis B et al. Regorafenib (BAY 73-4506) in advanced colorectal cancer: a phase I study. Br J Cancer. 2012;106(11):1722–1727. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, Sobrero Aet al. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial Lancet 2013381(9863):303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emura T, Suzuki N, Yamaguchi M, Ohshimo H, Fukushima M. A novel combination antimetabolite, TAS-102, exhibits antitumor activity in FU-resistant human cancer cells through a mechanism involving FTD incorporation in DNA. Int J Oncol. 2004;25(03):571–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mayer R J, Van Cutsem E, Falcone A et al. Randomized trial of TAS-102 for refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(20):1909–1919. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cancer Genome Atlas Network.Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer Nature 2012487(7407):330–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gridelli C, Ciardiello F, Gallo C et al. First-line erlotinib followed by second-line cisplatin-gemcitabine chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the TORCH randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(24):3002–3011. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ingold Heppner B, Behrens H M, Balschun K et al. HER2/neu testing in primary colorectal carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(10):1977–1984. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siena S, Sartore-Bianchi A, Lonardi Set al. Trastuzumab and lapatinib in HER2-amplified metastatic colorectal cancer patients (mCRC): the HERACLES trialJ Clin Oncol2015;33(Suppl):Abstract 3508

- 38.Wei G, Cam N, Patel R, Shoemaker R, Wild R, Li G.Overexpression of neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinases (NTRKs) as a potential therapeutic target for cancerProceedings of the 106th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; 2015 Apr 18–22; Philadelphia, PA. Philadelphia (PA).2015;75(15, Suppl):Abstract 127

- 39.De Braud F G, Niger M, Damian Set al. ALKA-372–001: First-in-human phase 1 study of entrectinib, an oral Pan-Trk, ROS1, and ALK inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors with relevant molecular alterationsJ Clin Oncol2015;33(Suppl):Abstract 2517

- 40.Burris H A, Brose M S, Shaw A Tet al. A first-in-human study of LOXO-101, a highly selective inhibitor of the tropomyosin receptor kinase (TRK) familyJ Clin Oncol2015;33(Suppl):Abstract TPS2624

- 41.Gravina G L, Senapedis W, McCauley D, Baloglu E, Shacham S, Festuccia C. Nucleo-cytoplasmic transport as a therapeutic target of cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2014;7:85. doi: 10.1186/s13045-014-0085-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen C, Garzon R, Gutierrez M et al. Safety, efficacy, and determination of the recommended phase 2 dose for the oral selective inhibitor of nuclear export (SINE) Selinexor (KPT-330) Blood. 2015;126:258. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abdul Razak A R, Mau-Soerensen M, Gabrail N Y et al. First-in-class, first-in-human phase I study of selinexor, a selective inhibitor of nuclear export, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(34):4142–4150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.3949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mitchell R A, Metz C N, Peng T, Bucala R. Sustained mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 activation by macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF). Regulatory role in cell proliferation and glucocorticoid action. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(25):18100–18106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.18100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bacher M, Metz C N, Calandra T et al. An essential regulatory role for macrophage migration inhibitory factor in T-cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(15):7849–7854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hussain F, Freissmuth M, Völkel D et al. Human anti-macrophage migration inhibitory factor antibodies inhibit growth of human prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12(07):1223–1234. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kerschbaumer R J, Rieger M, Völkel D et al. Neutralization of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) by fully human antibodies correlates with their specificity for the β-sheet structure of MIF. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(10):7446–7455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.329664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mahalingam D, Patel M R, Sachdev J Cet al. First-in-human, phase I study assessing imalumab (Bax69), a first-in-class anti-oxidized macrophage migration inhibitory factor (oxMIF) antibody in advanced solid tumorsJ Clin Oncol2015;33(Suppl):Abstract 2518

- 49.Luke J J, Ott P A, Shapiro G I. The biology and clinical development of MEK inhibitors for cancer. Drugs. 2014;74(18):2111–2128. doi: 10.1007/s40265-014-0315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cho M T, Lim D, Synold T Wet al. A phase I study of MEK162 and FOLFOX in chemotherapy-resistant metastatic colorectal cancerJ Clin Oncol2016;34(Suppl 4S):Abstract 679

- 51.Spreafico A, Tentler J J, Pitts T M et al. Rational combination of a MEK inhibitor, selumetinib, and the Wnt/calcium pathway modulator, cyclosporin A, in preclinical models of colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(15):4149–4162. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Novartis. BGJ398 Norvatis Web site.2016; Available at:http://www.novartisoncology.com/our-work/our-pipeline

- 53.Smyth E C, Sclafani F, Cunningham D. Emerging molecular targets in oncology: clinical potential of MET/hepatocyte growth-factor inhibitors. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:1001–1014. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S44941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bardelli A, Corso S, Bertotti A et al. Amplification of the MET receptor drives resistance to anti-EGFR therapies in colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov. 2013;3(06):658–673. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elisei R, Schlumberger M J, Müller S P et al. Cabozantinib in progressive medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(29):3639–3646. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Awasthi N, Schwarz R E. Profile of nintedanib in the treatment of solid tumors: the evidence to date. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:3691–3701. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S78805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Cutsem E, Prenen H, D'Haens G et al. A phase I/II, open-label, randomised study of nintedanib plus mFOLFOX6 versus bevacizumab plus mFOLFOX6 in first-line metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(10):2085–2091. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bhatt R S, Atkins M B. Molecular pathways: can activin-like kinase pathway inhibition enhance the limited efficacy of VEGF inhibitors? Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(11):2838–2845. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Simonelli M, Denlinger C S, Goff L Wet al. Phase 1 study of PF-03446962 (anti-ALK-1 mAb) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): correlation of tumor and serum biomarker data with disease controlJ Clin Oncol2014;(Suppl):Abstract 4095

- 60.Necchi A, Giannatempo P, Mariani L et al. PF-03446962, a fully-human monoclonal antibody against transforming growth-factor β (TGFβ) receptor ALK1, in pre-treated patients with urothelial cancer: an open label, single-group, phase 2 trial. Invest New Drugs. 2014;32(03):555–560. doi: 10.1007/s10637-014-0074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pedersen M W, Jacobsen H J, Koefoed K et al. Sym004: a novel synergistic anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody mixture with superior anticancer efficacy. Cancer Res. 2010;70(02):588–597. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dienstmann R, Patnaik A, Garcia-Carbonero R et al. Safety and activity of the first-in-class Sym004 anti-EGFR antibody mixture in patients with refractory colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(06):598–609. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schmoll H-J, Riera-Knorrenschild J, Kopp H-Get al. Maintenance therapy with the TLR-9 agonist MGN1703 in the phase II IMPACT study of metastatic colorectal cancer patients: a subgroup with improved overall survivalJ Clin Oncol2015;33(Suppl 3):Abstract 680

- 64.Lu H, Dietsch G N, Matthews M A et al. VTX-2337 is a novel TLR8 agonist that activates NK cells and augments ADCC. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(02):499–509. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dietsch G N, Lu H, Yang Y et al. Coordinated activation of toll-like receptor8 (TLR8) and NLRP3 by the TLR8 agonist, VTX-2337, ignites tumoricidal natural killer cell activity. PLoS One. 2016;11(02):e0148764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zachar Z, Marecek J, Maturo C et al. Non-redox-active lipoate derivates disrupt cancer cell mitochondrial metabolism and are potent anticancer agents in vivo. J Mol Med (Berl) 2011;89(11):1137–1148. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0785-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pardee T S, Lee K, Luddy J et al. A phase I study of the first-in-class antimitochondrial metabolism agent, CPI-613, in patients with advanced hematologic malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(20):5255–5264. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ganai A A, Farooqi H. Bioactivity of genistein: a review of in vitro and in vivo studies. Biomed Pharmacother. 2015;76:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2015.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Knight D C, Eden J A. Phytoestrogens--a short review. Maturitas. 1995;22(03):167–175. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(95)00937-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hwang J-T, Ha J, Park O J. Combination of 5-fluorouracil and genistein induces apoptosis synergistically in chemo-resistant cancer cells through the modulation of AMPK and COX-2 signaling pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;332(02):433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.04.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Robert C, Schachter J, Long G V et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2521–2532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Herbst R S, Baas P, Kim D Wet al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial Lancet 2016387(10027):1540–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dudley J C, Lin M T, Le D T, Eshleman J R. Microsatellite instability as a biomarker for PD-1 blockade. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(04):813–820. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brahmer J R, Tykodi S S, Chow L Q et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Topalian S L, Hodi F S, Brahmer J R et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Topalian S L, Drake C G, Pardoll D M. Targeting the PD-1/B7-H1(PD-L1) pathway to activate anti-tumor immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24(02):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kelderman S, Schumacher T N, Kvistborg P. Mismatch repair-deficient cancers are targets for anti-PD-1 therapy. Cancer Cell. 2015;28(01):11–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jacobs J, Smits E, Lardon F, Pauwels P, Deschoolmeester V. Immune checkpoint modulation in colorectal cancer: what's new and what to expect. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:158038. doi: 10.1155/2015/158038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Le D T, Uram J N, Wang H et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Greenwald R J, Boussiotis V A, Lorsbach R B, Abbas A K, Sharpe A H. CTLA-4 regulates induction of anergy in vivo. Immunity. 2001;14(02):145–155. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chung K Y, Gore I, Fong L et al. Phase II study of the anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 monoclonal antibody, tremelimumab, in patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(21):3485–3490. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.3994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Woo S R, Turnis M E, Goldberg M V et al. Immune inhibitory molecules LAG-3 and PD-1 synergistically regulate T-cell function to promote tumoral immune escape. Cancer Res. 2012;72(04):917–927. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thomas L J, He L Z, Marsh H, Keler T. Targeting human CD27 with an agonist antibody stimulates T-cell activation and antitumor immunity. OncoImmunology. 2014;3(01):e27255. doi: 10.4161/onci.27255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Petty J K, He K, Corless C L, Vetto J T, Weinberg A D. Survival in human colorectal cancer correlates with expression of the T-cell costimulatory molecule OX-40 (CD134) Am J Surg. 2002;183(05):512–518. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00831-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pedroza-Gonzalez A, Verhoef C, Ijzermans J N et al. Activated tumor-infiltrating CD4+ regulatory T cells restrain antitumor immunity in patients with primary or metastatic liver cancer. Hepatology. 2013;57(01):183–194. doi: 10.1002/hep.26013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bartkowiak T, Curran M A. 4-1BB agonists: multi-potent potentiators of tumor immunity. Front Oncol. 2015;5:117. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Page D B, Postow M A, Callahan M K, Allison J P, Wolchok J D. Immune modulation in cancer with antibodies. Annu Rev Med. 2014;65:185–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-092012-112807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Morgan R A, Dudley M E, Wunderlich J Ret al. Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes Science 2006314(5796):126–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dudley M E, Wunderlich J R, Yang J C et al. Adoptive cell transfer therapy following non-myeloablative but lymphodepleting chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(10):2346–2357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Robbins P F, Morgan R A, Feldman S A et al. Tumor regression in patients with metastatic synovial cell sarcoma and melanoma using genetically engineered lymphocytes reactive with NY-ESO-1. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(07):917–924. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Parkhurst M R, Yang J C, Langan R C et al. T cells targeting carcinoembryonic antigen can mediate regression of metastatic colorectal cancer but induce severe transient colitis. Mol Ther. 2011;19(03):620–626. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Porter D L, Levine B L, Kalos M, Bagg A, June C H. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(08):725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Maude S L, Frey N, Shaw P A et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(16):1507–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ma Q, Gonzalo-Daganzo R M, Junghans R P. Genetically engineered T cells as adoptive immunotherapy of cancer. Cancer Chemother Biol Response Modif. 2002;20:315–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Morgan R A, Yang J C, Kitano M, Dudley M E, Laurencot C M, Rosenberg S A. Case report of a serious adverse event following the administration of T cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor recognizing ERBB2. Mol Ther. 2010;18(04):843–851. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kershaw M H, Westwood J A, Darcy P K. Gene-engineered T cells for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(08):525–541. doi: 10.1038/nrc3565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Oh D Y, Venook A P, Fong L. On the verge: immunotherapy for colorectal carcinoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(08):970–978. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Uyl-de Groot C A, Vermorken J B, Hanna M G, Jret al. Immunotherapy with autologous tumor cell-BCG vaccine in patients with colon cancer: a prospective study of medical and economic benefits Vaccine 200523(17-18):2379–2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gollamudi R, Ghalib M H, Desai K K et al. Intravenous administration of Reolysin, a live replication competent RNA virus is safe in patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest New Drugs. 2010;28(05):641–649. doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9279-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]