Abstract

Mucin-4 (Muc4) is a large cell surface glycoprotein implicated in the protection and lubrication of epithelial structures. Previous studies suggest that aberrantly expressed Muc4 can influence the adhesiveness, proliferation, viability and invasiveness of cultured tumor cells, as well as the growth rate and metastatic efficiency of xenografted tumors. While it has been suggested that one of the major mechanisms by which Muc4 potentiates tumor progression is via its engagement of the ErbB2/HER2 receptor tyrosine kinase, other mechanisms exist and remain to be delineated. Moreover, the requirement for endogenous Muc4 for tumor growth progression has not been previously explored in the context of gene ablation. To assess the contribution of endogenous Muc4 to mammary tumor growth properties, we first created a genetically-engineered mouse line lacking functional Muc4 (Muc4ko), and then crossed these animals with the NDL model of ErbB2-induced mammary tumorigenesis. We observed that Muc4ko animals are fertile and develop normally, and adult mice exhibit no overt tissue abnormalities. In tumor studies, we observed that although some markers of tumor growth such as vascularity and cyclin D1 expression are suppressed, primary mammary tumors from Muc4ko/NDL female mice exhibit similar latencies and growth rates as Muc4wt/NDL animals. However, the presence of lung metastases is markedly suppressed in Muc4ko/NDL mice. Interestingly, histological analysis of lung lesions from Muc4ko/NDL mice revealed a reduced association of disseminated cells with red and white blood cells. Moreover, isolated cells derived from Muc4ko/NDL tumors interact with fewer blood cells when injected directly into the vasculature or diluted into blood from wild type mice. We further observed that blood cells more efficiently promote the viability of non-adherent Muc4wt/NDL cells than Muc4ko/NDL cells. Together, our observations suggest that Muc4 may facilitate metastasis by promoting the association of circulating tumor cells with blood cells to augment tumor cell survival in circulation.

Keywords: Breast cancer, HER2/ErbB2, mucin, Muc4, metastasis

Introduction

Metastasis is a fundamentally complex and inefficient process where a minority of cancer cells will migrate from the primary tumor, invade the vasculature, survive the harsh conditions of vascular transit and colonize new tissues25. Consequently, few metastases arise despite the potential for tumors to shed millions of cells into circulation5,10,25. Nevertheless, metastatic disease is the leading cause of cancer-associated mortality and is strongly associated with relapse following therapeutic intervention28,30,34. As such, there is an urgent need to understand the molecular determinants of metastasis to improve patient outcomes and optimize clinical disease management.

Mucin-4 (Muc4) is a large cell surface glycoprotein, composed of a heavily O-glycosylated extracellular alpha subunit and a membrane-anchored beta subunit that normally functions to lubricate and protect apical epithelial surfaces4. Several studies indicate that Muc4 augments cellular properties associated with the metastatic potential of carcinoma cells, and we have demonstrated that Muc4 protein is elevated in metastatic lesions compared to patient-matched primary breast tumors, strongly suggesting that Muc4 confers an advantage to metastasizing tumor cells50.

Although the precise mechanisms by which Muc4 contributes to metastasis remain to be delineated, there are several plausible hypotheses. The bulky alpha subunit of Muc4 may promote dislodgement of tumor cells from the primary mass, enhancing invasion into the surrounding matrix. Indeed, Muc4 has been reported to enhance the motility, invasiveness and metastatic capacity of pancreatic and melanoma cancer cells6,22,23,41,46, inhibit cell-to-cell or cell-to-matrix interactions6,20, and promote the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) upon overexpression in prostate cancer cells38,41.

Muc4 may also prepare tumor cells for hematogenous dissemination. The alpha subunit could serve as a physical barrier to attachment and as a sensor of biochemical changes in the extracellular milieu, reflected by its protective role in secretory epithelium4,47. The alpha subunit may likewise enable movement of tumor cells into the vasculature via glycan-directed interactions with soluble factors and adhesion molecules. Along these lines, Muc4-galectin complexes promoted endothelial adhesion in a pancreatic cancer model44, an interaction that may also facilitate extravasation at the metastatic site and inhibit suspension-induced cell death, or anoikis17,55. Interestingly however, our group established that Muc4 overexpression not only promotes cell survival in growth factor depleted conditions and inhibits anoikis, but that these effects occur independently of the alpha subunit51. Taken together, these observations suggest that Muc4 upregulation may be a multifaceted adaptation that permits tumor cell survival during vascular transit to facilitate colonization at distant sites.

The most well documented role of Muc4 in the context of cancer is its capacity to modulate receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. In particular, Muc4 augments ErbB2/HER2 receptor-mediated signaling in breast, melanoma, ovarian and pancreatic cancer cell models3,8,12,37,39. These findings are significant in that ErbB2/HER2 correlates with substantially lower overall survival rates, shorter disease-free intervals and increased incidence of metastasis18,48. However, the contribution of endogenous Muc4 to ErbB2-mediated cancer onset and progression has not been explored. Here we employ a Muc4 knockout mouse to demonstrate Muc4 is dispensable for the efficient growth of ErbB2-induced primary mouse mammary tumors, but significantly enhances the occurrence of lung metastases. We further demonstrate that while endogenous Muc4 is sufficient to promote survival of tumor cells in suspension conditions, overall viability is greatly enhanced in the presence of platelets and immune cells. These observations firmly establish Muc4 as a mediator of metastasis, likely acting as a critical factor during vascular transit.

Results

Creation and characterization of Muc4tm1Unc mutant mice

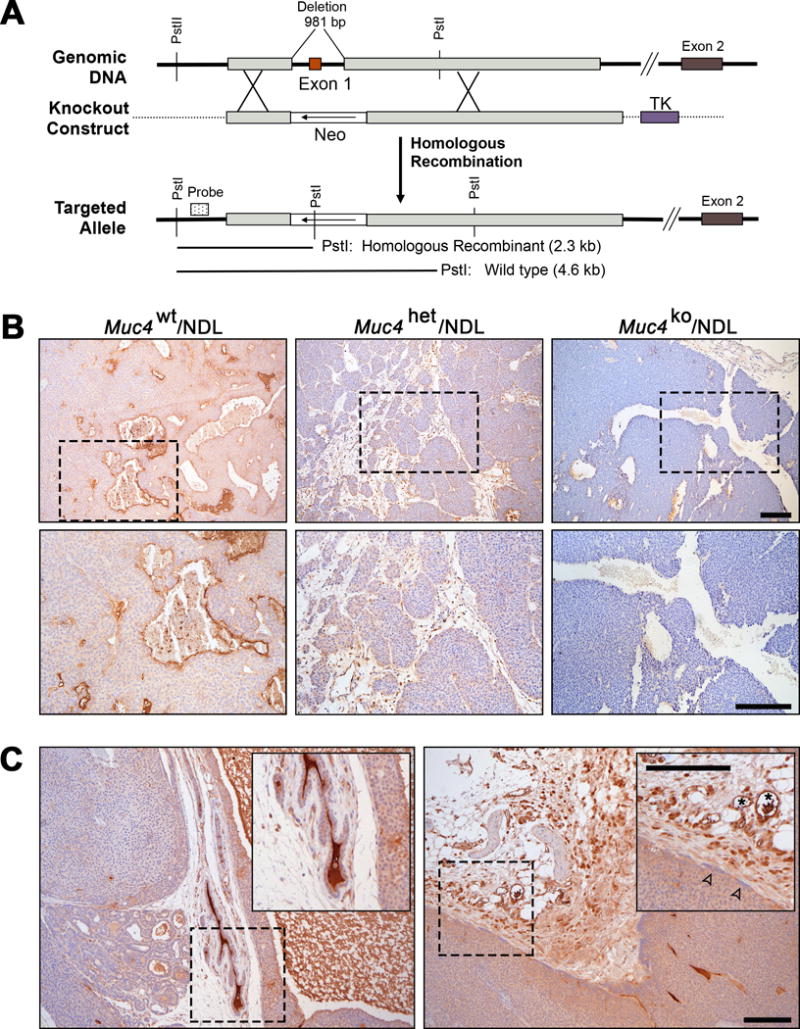

Muc4-deficient mice were generated using a targeting vector that replaces 981bp of genomic sequence containing the starting methionine in exon 1 with a reverse-oriented floxed MC1-neo cassette, and includes a PGK-TK cassette for negative selection (Figure 1A). Muc4tm1Unc founder animals were generated via homologous recombination on a mixed SV129:FvB/NJ background, and progeny were back-crossed at least ten generations onto the FvB/NJ strain prior to phenotypic analysis. Mice heterozygous for Muc4 were interbred to generate all genotypes designated here as wild type (Muc4wt), heterozygous (Muc4het), and knockout (Muc4ko). Muc4 disruption was confirmed at the transcript (Supplemental Figure 1A) and protein levels (Supplemental Figure 1B). No discernable effects of Muc4 disruption on viability, breeding or lactation were observed, and no differences in mammary gland architecture were noted between genotypes in adult virgin mammary glands (Supplemental Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Muc4 is effectively depleted by targeted knockdown.

(A) The strategy employed to functionally delete the murine Muc4 gene is depicted. Homologous recombination of the targeting vector with genomic Muc4 replaces exon 1 with a neomycin resistance cassette (Neo) transcribed in the direction indicated by the arrow; thymidine kinase (TK) in the targeting vector was included for negative selection. Insertion of Neo introduced a Pst1 restriction site that was used to confirm knockout in ES cells by Southern blot (not shown) using the probe indicated by the dotted box. The schematic is not shown to scale. (B) Functional deletion of Muc4 in NDL mammary tumor tissue was confirmed by immunohistochemistry using an antibody that detects the beta subunit of Muc4. Representative images were selected from at least three biological replicates. (C) Representative images selected from at least three biological replicates highlighting the variability in the level of Muc4 expression between the primary mass and its adjacent tissues. Muc4 protein expression was detected as described above. Normal adjacent mammary ducts (left panel) and stromal tissues (right panel) exhibit robust expression of Muc4. Boxed regions have been expanded to show detail (insets). Muc4 positivity was also noted in blood vessels (right inset, asterisk), as previously described50. Tumors have comparably weaker expression of Muc4, even at the invasive edge (right panel inset, open arrowheads). Scale bars in all images = 250μm.

Muc4 disruption does not delay mammary tumor onset or inhibit tumor growth

Previous studies indicate that Muc4 physically interacts with ErbB2 (ref 3) to augment its signaling either directly51 or indirectly via stabilization of ErbB2-ErbB3 receptor heterodimers12. Accordingly, Muc4 may potentiate ErbB2 pro-tumorigenic signaling to enhance tumorigenesis. To explore this postulate, we interbred Muc4tm1Unc FvB/NJ with a well-characterized mouse model in which an activated rat c-erbB2/neu allele (Neu DeLetion mutant, NDL) transgene is under the control of the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter (MMTV)16. The MMTV-NDL mouse forms highly metastatic multifocal tumors at approximately 20 weeks of age16. Absence of Muc4 protein in mammary tumors of Muc4ko/NDL relative to Muc4wt/NDL and Muc4het/NDL female mice was confirmed by immunohistochemistry (Figure 1B).

Interestingly, Muc4wt/NDL tumors exhibited variable protein expression, with adjacent normal and stromal tissues exhibiting the most robust immunoreactivity for Muc4 beta when compared to the primary mass (Figure 1C). These data are consistent with our previous findings in human tissues, where Muc4 protein expression is down-regulated in primary breast tumors relative to matched normal tissue or lymph node metastases50. Muc4 also is not specifically elevated in tumor cells exhibiting signs of invasiveness (i.e. aligned at the leading edge of the tumor; see Figure 1C right panel inset, closed arrowheads), supportive of a relatively minor role for Muc4 during primary tumor growth and local invasion.

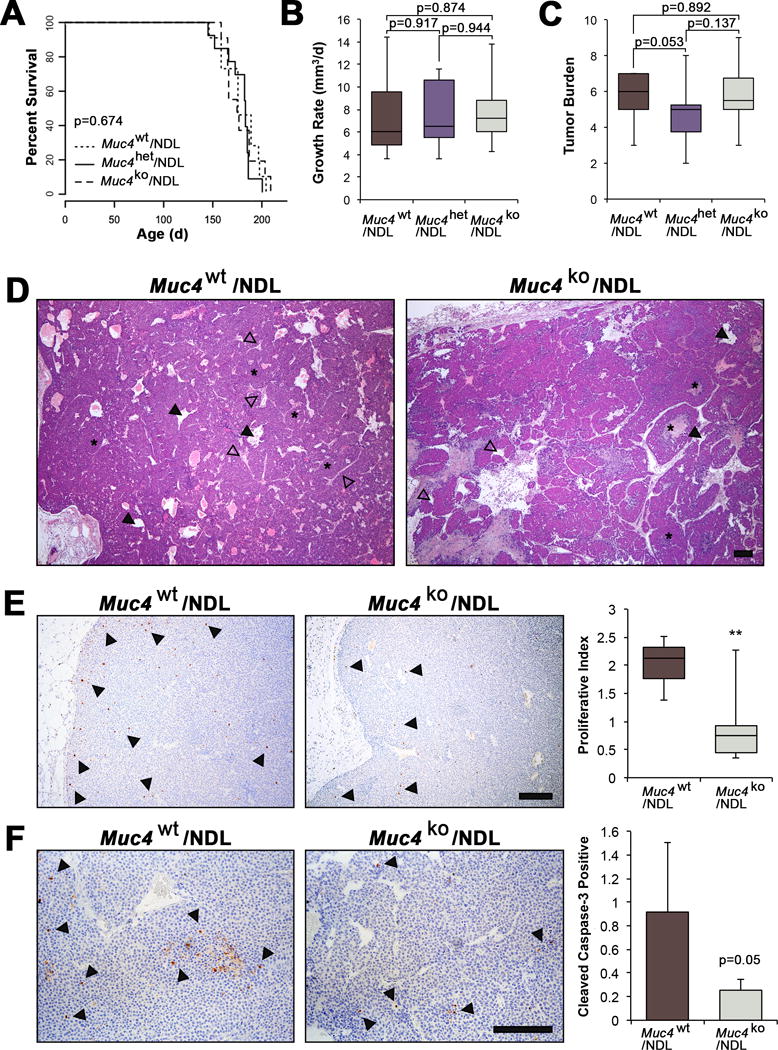

In support of this, we observed that Muc4wt/NDL, Muc4het/NDL and Muc4ko/NDL tumors emerge and grow with remarkably similar kinetics; no significant differences were apparent among genotypes in latency to tumor formation (Supplemental Figure 2A), the time necessary for tumors to reach an approximate diameter of 20mm (Figure 2A), average growth rates (Figure 2B), or in overall tumor burden (Figure 2C). The histopathology of Muc4wt/NDL and Muc4ko/NDL tumors were generally comparable, appearing as well-differentiated, heterogeneous mammary adenocarcinomas characteristic of the NDL model16,45 (Figure 2D). Notably, Muc4ko/NDL lesions tended to be more cystic when compared to Muc4wt/NDL tumors (Supplemental Figure 2B), although this feature was not statistically significant (p=0.09).

Figure 2. Muc4 deletion modestly alters primary mammary tumor histology but does not affect mammary tumor latency or growth rate in the NDL model.

(A-C) Survival curves and box plots depicting Muc4/NDL tumor growth characteristics. Latency to tumor formation (A), tumor growth rate (B), and the overall tumor burden (number of glands with tumors) (C), were not significantly different among genotypes (Muc4wt/NDL [n=13], Muc4het/NDL [n=14] and Muc4ko/NDL [n=12]). Data are presented as means ± SD and significance determined by log-rank test (A) or 2-sided Students-t test (B-C). (D) Representative H&E images are depicted of formalin fixed, paraffin embedded sections from Muc4wt/NDL and Muc4ko/NDL primary tumors. Tumors from both genotypes develop as heterogeneous mammary adenocarcinomas displaying nests of tumor epithelium (asterisks) and abundant lumina (closed arrowheads) that are structurally distinct from endothelial lined blood vessels (open arrowheads). (E) Representative images Muc4wt/NDL and Muc4ko/NDL primary tumor tissues following immunodetection of the proliferation marker phospho-histone H3. Quantification of at least six biological replicates revealed a significant reduction in the number of proliferating cells with loss of Muc4 (**, P<0.01; t-test). The percent of pH3 positive cells/total cells is plotted. Examples of positive nuclei are denoted by closed arrowheads. (F) Immunodetection of cleaved caspase-3 suggests a modest yet insignificant reduction in the rate of apoptosis with Muc4 loss (P=0.05; t-test). Data are averages from at least five biological replicates and expressed as the percent of total cells positive for cleaved caspase-3 ± SD, where examples of positive cells are indicated with closed arrowheads. Scale bars in all images = 250μm.

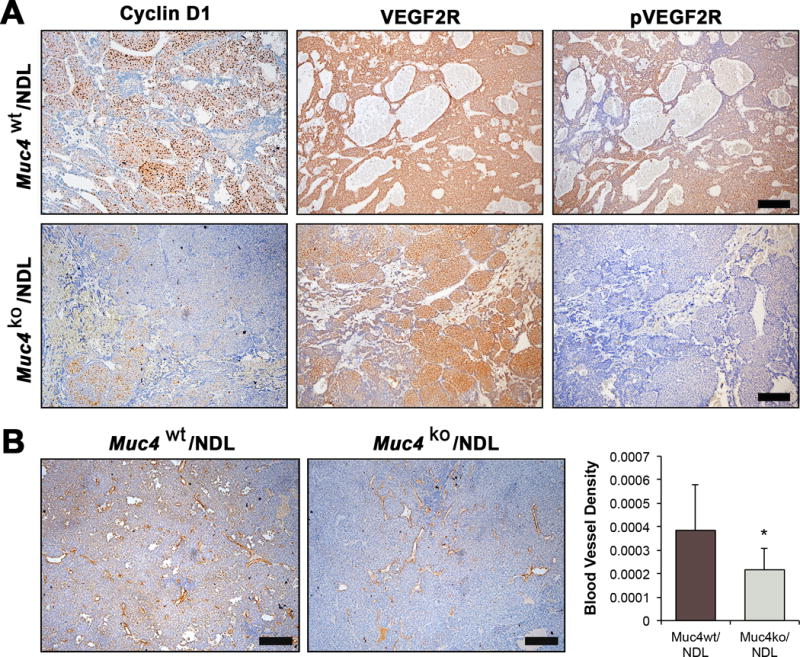

The similar growth rates between genotypes could be explained by relative rates of cell turnover, as Muc4wt/NDL tumors had higher levels of both proliferation (Figure 2E) and apoptosis (Figure 2F) when compared to Muc4ko/NDL tumors. Interestingly, Muc4ko/NDL tumors expressed considerably lower levels of cyclin D1 (Figure 3A) and phosphorylated tumor cell-expressed vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (pVEGF2R; Figure 3A), reflective of reduced angiogenic factor production. Consistent with the suppression of angiogenic signaling, we found a significant reduction in Muc4ko/NDL tumor vascularity as indicated by poor immunoreactivity for the endothelial marker, CD31 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Muc4 deletion has potent effects on protein expression and vascularity.

(A) Muc4wt/NDL (n=7) and Muc4ko/NDL (n=8) tumors were stained for cyclin D1, and scored on a scale of 0-3 (0=negative, 3=strong; not shown). Mann Whitney U test revealed significantly lower cyclin D1 expression in Muc4ko/NDL tumors (P < 0.01). Similarly, the expression of phosphorylated VEGF2R (pVEGF2R) is increased in Muc4wt/NDL tumors relative to Muc4ko/NDL tumors. Total VEGF2R was visually similar between the two genotypes. (B) Primary tumors were stained for CD31 to calculate blood vessel density (percent of CD31 positive vessels/area). Student’s t-test revealed Muc4wt/NDL tumors exhibit significantly elevated vascular content compared to Muc4ko/NDL tumors (*, P<0.05). Images are representative of at least seven biological replicates. Scale bars in all images = 250μm.

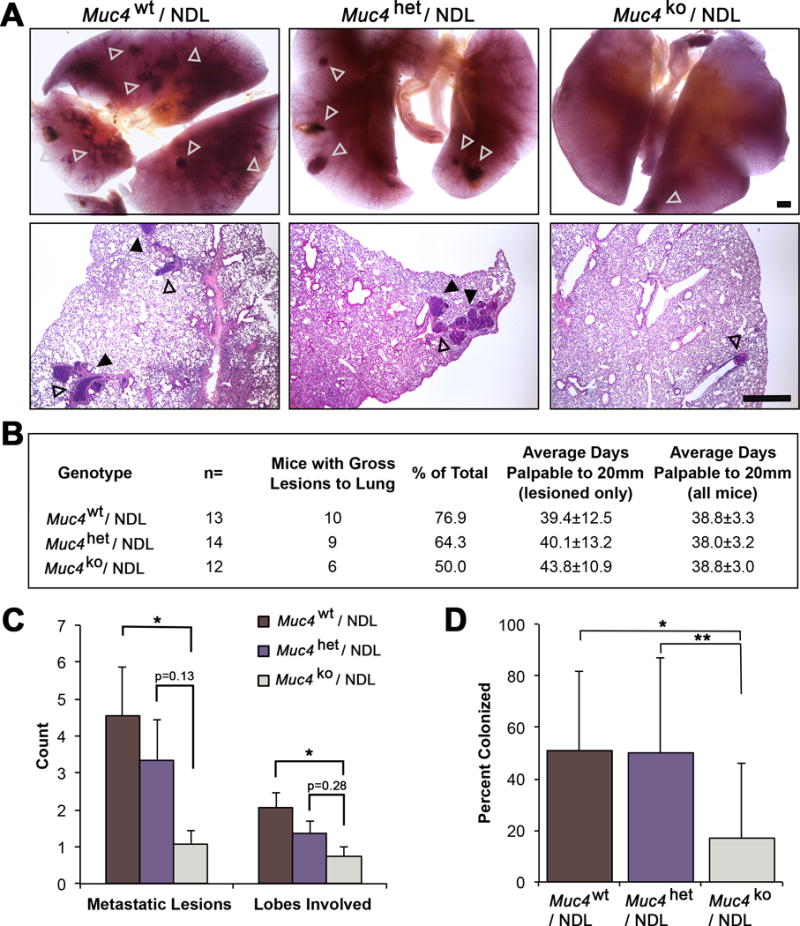

Muc4 disruption suppresses metastasis

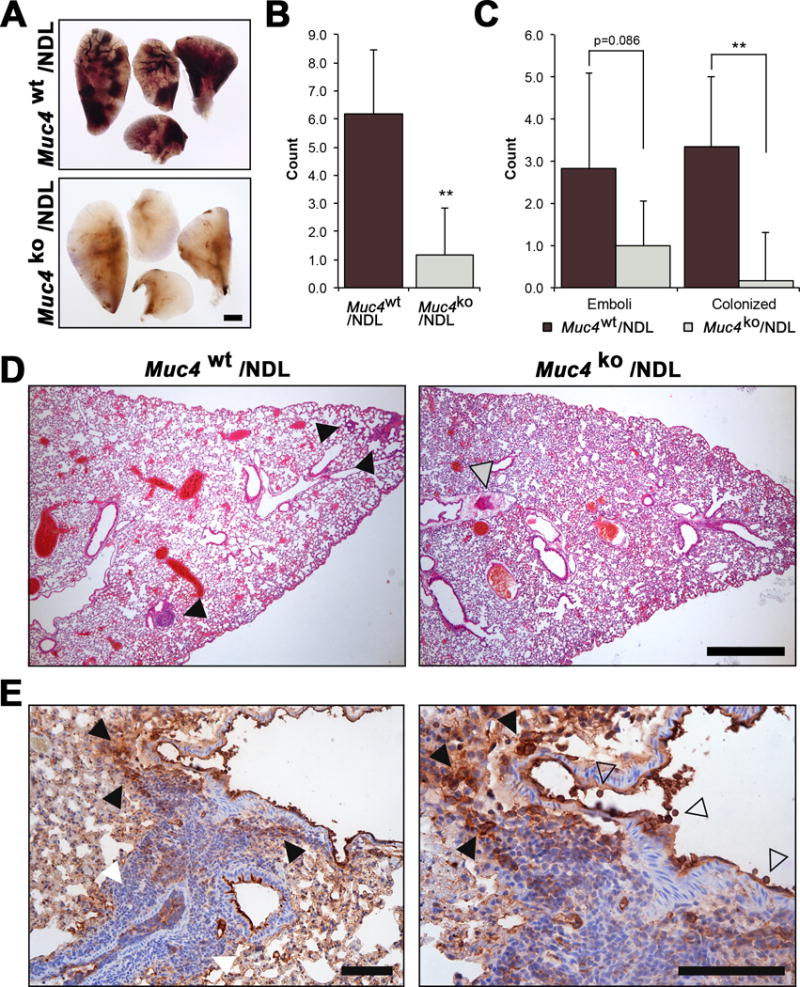

Our previous studies indicate that Muc4 protein is upregulated in lymph node metastatic lesions relative to patient-matched primary breast tumors50, raising the possibility that Muc4 actively contributes to the metastatic process. Therefore, we analyzed lung tissue by gross morphology and histology (Figure 4A) and observed that, indeed, Muc4ko/NDL tumors are less metastatic than Muc4wt/NDL and Muc4het/NDL, despite primary lesions having been carried for similar amounts of time and to the same endpoint (Figure 4B). Not only did Muc4 expression enhance the penetrance of lesions to the lung (Figure 4B), it also substantially increased the total metastatic burden (Figure 4C) and extent of colonization to the lung parenchyma (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Muc4 deletion markedly suppresses metastasis to the lung.

(A) Carmine alum stained lung tissue from Muc4wt/NDL, Muc4het/NDL and Muc4ko/NDL mice were evaluated for the occurrence of gross lesions (open arrowheads) under a dissecting microscope. Lesions were subsequently isolated, embedded in paraffin and sectioned for further evaluation by routine histology. Metastatic lesions were classified as either emboli (contained within vascular walls; open arrowheads) or colonized (within lung parenchyma; closed arrowheads). Representative H&E stained sections are depicted. Scale bar = 1mm. (B) Lung tissues from multiple mice were evaluated for the occurrence of gross and microlesions (n=9 Muc4wt/NDL; n=8 Muc4het/NDL; n=9 Muc4ko/NDL). The numbers of mice bearing metastatic lesions is compared to the corresponding primary tumor latencies and growth rates for each genotype. (C) The numbers of gross metastatic lesions and involved lung lobes per mouse (mean ± SD) are depicted for the three genotypes. Significance was determined by Mann Whitney test with continuity correction. (D) The percent (mean ± SD) colonized lesions is plotted for each genotype. Student’s t-test revealed a significant difference in the percent of colonizing lesions. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 for all panels.

We next examined whether Muc4 expression affects pro-metastatic factors that may permit the survival, migratory, or invasive capacities of tumor cells. We found that Muc4 deletion correlates with dramatic reductions in proteins commonly associated with EMT including twist 1/2 and vimentin (Supplemental Figure 3A) are respectively substantially and modestly reduced in Muc4ko/NDL tumors. Lung metastases exhibited similar trends, where vimentin is elevated in Muc4wt/NDL lesions compared to Muc4ko/NDL (Supplemental Figure 3B). While we anticipated that reductions in EMT-associated proteins would attenuate migration, we observed no differences in the abilities of ex vivo dissociated tumor cells to migrate in a transwell assay (Supplemental Figure 3C). Taken together, these data suggest that Muc4 dramatically modifies tumor protein expression but that these alterations are not sufficient to elevate migratory capacity.

Muc4 may facilitate metastasis via physical interactions with blood cells

Disrupted VEGFR signaling may reduce both the abundance and permeability of the tumor-associated vascular bed35 and therefore the relative efficiency of NDL cells to access essential networks for metastasis. Accordingly, we evaluated whether Muc4 benefited tumor cells even when given equal access to vasculature. Indeed, Muc4wt/NDL cells instilled directly to the lateral tail vein generated more metastatic lesions to the lung compared to Muc4ko/NDL cells (Figures 5A and 5B). When lesions were stratified by type (colonized, emboli), we found a significant difference in the capacity of Muc4wt/NDL cells to colonize the lung parenchyma (Figures 5C and 5D). It is likely Muc4 conveys a significant survival advantage to tumor cells, reflected in the enhanced viability of Muc4wt/NDL cells when subjected to an anoikis assay in vitro (Supplemental Figure 4A). Finally, we observed that Muc4 may be specifically upregulated during vascular transit, as its expression appeared to be strongest in tumor cells found either within or in close proximity to vascular lumens and reduced in established lung lesions (Figure 5E).

Figure 5. Muc4 deletion impairs the metastatic capacity of tail vein injected NDL cells.

Pooled (n=4 independent biological sources per line) primary Muc4wt/NDL and Muc4ko/NDL tumor cells were instilled into the lateral tail vein of FVB wt mice (n=6). Tissues (lungs, digestive tract, liver, spleen, uterus, brain) were collected 28d later, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and evaluated for the appearance of gross metastasis. Only lungs were found to contain gross lesions, more readily visible by carmine alum stain (A). Scale bar = 1mm. (B-D). H&E stained sections were used to quantify the occurrence of metastatic lesions. The total number of metastases (B) and the frequency of colonized lesions (C) formed in the lungs of mice injected with Muc4wt/NDL cells was significantly increased compared to those receiving Muc4ko/NDL cells. There was a modest reduction in the frequency of emboli formed by Muc4ko/NDL cells (P = 0.086). Representative H&E stained sections are presented in (D). Closed grey arrowhead, emboli; closed black arrowhead, colonized lesion. Scale bar = 1mm. (E) The level of Muc4 expression within a colonized lesion is heterogeneous, where it is strong both within (open arrowhead) and around the vascular lumen (closed black arrowhead) but is decreased in tumor cells found further away from this region (closed white arrowhead). Tissue was stained with an antibody to Muc4 beta, as described in Figures 1B and 1C. Scale bar = 150μm.

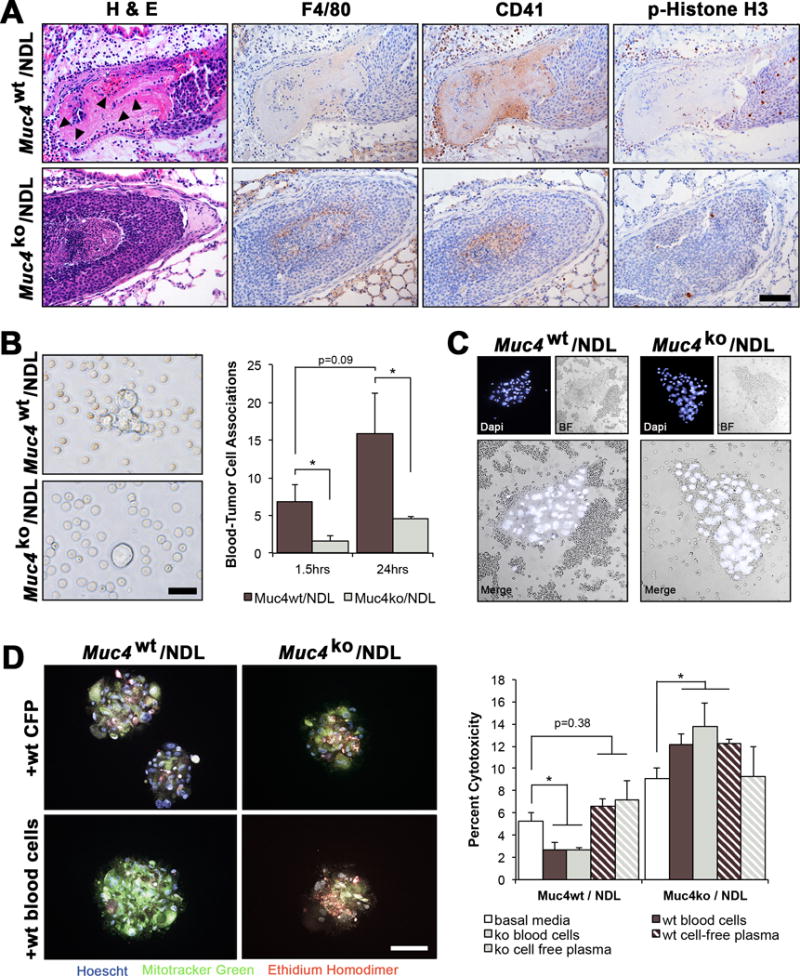

Disseminated tumor cells are known to travel as complex aggregates, consisting of clusters of cancer cells, platelets and other blood cells. These microthrombi are thought to critically improve tumor-cell survival and extravasation by promoting long-term adhesion and arrest within microvasculature, while shielding tumor cells from the shear stress imposed during transit in circulation25. To explore whether some of the pro-metastatic effects of Muc4 could arise from tumor cell interactions with platelets and other blood cell components, we first histologically assessed the association of tumor cells with blood cells in lung lesions. By standard hematoxylin and eosin staining, we noted a substantial increase in the abundance of platelets and immune cells within Muc4wt/NDL relative to Muc4ko/NDL emboli (H&E, Figure 6A; arrowheads), further verified by specific staining for macrophages (F4/80) and platelets (CD41, Figure 6A). A majority of the cells were immunoreactive for CD41, suggesting an abundance of platelets and/or hematopoietic progenitors31 although it is unclear whether they infiltrated the lesion locally at the lung or if they were a component of the original circulating microthrombi. Nevertheless, Muc4wt/NDL lesions were more proliferative when compared to Muc4ko/NDL lesions (phosoho-histone H3, Figure 6A), a feature which may partially account for differences in colonizing ability.

Figure 6. Deletion of Muc4 suppresses the association of tumor cells with red and white blood cells in vitro and in vivo.

(A) Representative H&E stained lung lesions from Muc4wt/NDL and Muc4ko/NDL mice, illustrating the elevated abundance of blood cells (closed arrowheads) in Muc4wt/NDL emboli. Immunodetection of proteins specific to macrophages (F4/80) and platelets, megakaryocytes and hematopoietic progenitors (CD41/Integrin alpha 2b) indicated the majority of associated blood cells to be CD41 positive. Phospho-histone H3 (pH3) staining revealed Muc4wt/NDL lung lesions were more proliferative than Muc4ko/NDL lesions. Scale bar in all images = 100μm. Images are representative of at least 6 biological replicates. (B) Quantification of tumor cell-blood cell associations (proximity of < 5μm) using bright field microscopy of live cells revealed a reduced number of associated blood cells at either 1.5hrs or 24hrs after the initiation of co-culture conditions. Pooled NDL cells (n=4 biological sources per line) were used for these experiments and data are presented as averages of three independent experiments ± SD. Scale bar = 50μm. *, P < 0.05. (C) Similar associations were noted for Muc4wt/NDL cells in vivo, where the abundance of closely associated blood cells appears visibly enhanced by the presence of Muc4. Pooled Muc4wt/NDL or Muc4ko/NDL cells (n=4 biological sources per line) were instilled into the lateral tail vein of female mice (n=4 per line) and whole blood was collected by cardiac puncture 3d later and immediately fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Nuclei were stained with DAPI and individual cell clusters imaged by fluorescence and bright field microscopy. Scale bar = 200μm. (D) Muc4-mediated tumor cell association with blood cells promotes tumor cell viability in suspension. Primary Muc4wt/NDL and Muc4ko/NDL tumor cells (n=3 per line) were labeled with MitoFluor green, and cultured in suspension for 24hrs after admixing with basal media, freshly harvested blood cells in basal media, or cell free-plasma (CFP) in basal media harvested from Muc4wt or Muc4ko mice. Hoechst 33342 was used as a nuclear stain to discern platelets from immune and tumor cells, and MitoFluor green was used to distinguish tumor cells from immune cells. Percent cytotoxicity (mean ± SD) was determined within tumor sphere aggregates by positive staining for ethidium homodimer. Student’s t-test revealed blood cells significantly suppress the death of Muc4wt/NDL but not Muc4ko/NDL cells. The origin of the blood cells (Muc4wt or Muc4ko) did not affect outcomes. Images are presented as final merged composites. Unmerged images may be found in Supplemental Figure 4B. Scale bar = 200μm. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

To explore whether the presence of Muc4 enhances the interaction of tumor and blood cells, we developed an in vitro suspension assay in which blood cells were admixed with either Muc4wt/NDL or Muc4ko/NDL tumor cells. After 1.5hrs and 24hrs, we noted a significant increase in the number of blood cells that were closely associated with individual Muc4wt/NDL tumor cells or tumor cell aggregates (Figure 6B and Supplemental Movies 1 and 2; P <0.05). Importantly, we found similar interactions to occur in vivo, where tail vein injected Muc4wt/NDL cells were more likely to be found with large clusters of blood cells (Figure 6C).

It is likely the physical interaction of Muc4 with blood cells is requisite for survival, suggested by enhanced survival (Figure 6D and Supplemental Figure 4B) and sphere forming capacity (Supplemental Figure 4C) only when Muc4wt/NDL cells were directly co-cultured with blood cells. These effects relied solely on the status of Muc4 in the tumor cell, as blood cells derived from Muc4ko and Muc4wt mice were equally capable of improving the viability of suspension cultured Muc4wt/NDL cells (Figure 6D).

Discussion

In the context of cancer, Muc4 has been shown to initiate signaling cascades through interactions with members of the ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases. In particular, the association of Muc4 with ErbB2/HER2 enforces receptor complex stability at the plasma membrane and potentiates tyrosine phosphorylation of ErbB2 to augment cellular differentiation, proliferation and survival3,4,12. We now provide appreciable insight into Muc4 biology by establishing its primary role in the malignant progression of ErbB2-overexpressing mammary carcinomas. While we found that Muc4 is dispensable for primary tumor growth, it significantly augments the efficiency of metastasis, reflected by an increased occurrence, burden and colonization of secondary lesions in the lung. We provide further mechanistic insight that Muc4 engages a complex survival strategy that is likely to encompass both intrinsic signaling and intercellular interactions during the hematogenous dissemination of tumor cells.

These findings are significant, as vascular transit represents a particularly vulnerable stage of metastasis, where tumor cells must remain viable under suspension conditions, withstand significant shear stresses and evade immune surveillance25. Disseminated tumor cells are thought to interact with immune cells and platelets13,25, which may potentiate their demise15 or promote their survival2,14,40. For example, a recent study demonstrated metastatic colonization of breast cancer cells to the lung was aided by the formation of extracellular nets by neutrophils, ostensibly facilitating expansion of lodged tumor cells36. Recruitment of neutrophils and other leukocytes may be accomplished by the formation of platelet-tumor cell aggregates, which would be more likely to become entrapped in microvessels than individual cancer cells25. In turn, clot formation may enhance survival, early niche creation and extravasation via recruitment of macrophages to the site of arrest14.

The association of platelets with disseminated cancer cells is so pervasive that platelets or platelet mimics are currently being engineered as anti-cancer therapeutics to deliver cytotoxic agents to tumor cells19,26,27. On the other hand, inhibition of platelet aggregation11,13 or immune cell function14,36,40 is sufficient to impede metastasis. Our observations strongly suggest that Muc4 is an essential component of such blood cell-tumor cell interactions, reflected by the association of platelets and immune cells with both circulating and lodged Muc4wt/NDL cells. Further to this, our in vitro studies suggest this interaction enhances the survival of Muc4-expressing cells under suspension conditions, as might be expected during vascular transit.

These data impart additional complexity to our understanding of Muc4. Previous reports imply that Muc4 protects circulating tumor cells from immune destruction21 as a result of the ability of its bulky glycosylated extracellular region to mask surface epitopes and inhibit immune recognition7. While our data do not directly refute or support this model, we found no decrease in the survival in Muc4ko/NDL cells when co-cultured with blood cells, suggesting that viability is not based on immune destruction per se. It is worth noting a recent study in which Muc4 was enhanced in both chronic and acute models of inflammation29, lending further credence to the postulate that Muc4 acts as a critical survival factor during periods of heightened immune response.

Beyond demonstrating a pro-survival function of Muc4, we provide evidence that it is required for robust tumor angiogenesis. Along these lines, Muc4ko/NDL tumors exhibited reduced phosphorylation of VEGFR2R and blood vessel formation, suggesting that differences in the rate of metastasis may partially depend on the relative abundance of vessels in which to invade. Previous reports indicate that Muc4 is expressed by differentiated endothelial cells, is associated with the luminal surfaces of blood vessels50,53,54 and when knocked down attenuates VEGF expression and angiogenesis56. Whether Muc4 presence in endothelial or epithelial cells is essential or permissive for blood vessel formation has yet to be established. However, its specific upregulation in endothelium during intermediate stages of wound-induced angiogenesis54, and its association with epithelium-derived regulators such as ErbB2 (refs 24,32), β-catenin and VEGF56, point to possible roles. While our current model precludes extensive investigation of the differential requirements for epithelial and endothelial Muc4 in angiogenesis, future cross-transplantation studies in which Muc4 replete epithelium is transplanted into knockout stromal tissue and vice versa may yield valuable insight.

We also found expression of proteins implicated in EMT (twist and vimentin) to be markedly attenuated in the absence of Muc4. While we were unable to demonstrate a significant difference in migratory capacity with a loss of Muc4, the dramatic reduction in both metastasis and in the expression of key metastatic drivers suggest it as a potential therapeutic target, especially in the context of HER2-positive breast carcinomas.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Muc4tm1Unc mice

The University of North Carolina (UNC) Animal Models Core (Chapel Hill, NC, USA) generated Muc4-deficient mice via homologous recombination in mouse embryonic stem cells. Briefly, a 129SvEv BAC mouse genomic library was screened for Muc4 genomic sequences containing exon 1 using two Muc4 cloned sequences (a 430bp fragment from 6824-7254 and a 347 bp fragment from 10716-11063 of sequence NM_080457). Short and long arm homologous fragments were cloned from the Muc4 genomic BAC into targeting vector pOSdupdel6142-SA vector to generate the targeting vector pOSdupdel6142-Muc4 which was electroporated into 129SvEv embryonic stem (ES) cells. ES cell clones with the targeted recombination event were selected with Geneticin and ganciclovir, screened by PCR and confirmed by Southern blot (not shown) prior to injection into FvB/NJ blastocysts to generate chimeric founders. Founder males from identified ES cell lines were crossed to FvB/NJ female mice to yield Muc4tm1Unc mice heterozygous for the targeted allele, and these were then crossed to initiate Muc4tm1Unc lines. Nomenclature was developed in accord with the International Committee on Standardized Genetic Nomenclature for Mice as implemented by the Mouse Genomic Nomenclature Committee. Loss of Muc4 protein was confirmed with a Muc4 mouse monoclonal antibody to the beta subunit as described50.

Generation of Muc4/NDL mice

All experimental protocols were approved by the IACUC of the University of California, Davis, USA. The NDL mouse model has previously been described45. Muc4het females were crossed with NDL males to generate Muc4wt/NDL, Muc4het/NDL and Muc4ko/NDL genotypes. Genotypes were confirmed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) by commercial vendor (Muc4, Transnetyx, Cordova, TN USA) or in house (NDL) using primers for Muc4 (Fwd-AGCTAAAGAATGTGGCCATAAAGGA; Rvs-CGTTCCCACCATCCTCCAAAA), neomycin (Fwd-GGGCGCCCGGTTCTT; Rvs-CCTCGTCCTGCAGTTCATTCA) and NDL (Fwd-TTC CGG AAC CCA CAT CAG; Rvs- GTT TCC TGC AGC AGC CTA).

Quantitative PCR

Tissue was homogenized in Trizol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA, USA) by Dounce homogenizer per manufacturer’s guidelines. Total RNA was purified using an RNA purification kit (Thermo, Cat# 12183025) and complementary DNA prepared as described52. Quantitative PCR was carried out as described49 using probe sets specific for Muc4 (mm0046688_m1) with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, 435293E) used for normalization.

Tumor monitoring and analysis

Mammary tumors were palpated twice weekly in female NDL mice commencing at 12 weeks of age by a single investigator partially blinded to genotypes. As tumors form in multiple mammary glands in the NDL model45, the growth rates of all tumors were recorded by caliper measurements. The leading tumor was allowed to reach a maximum diameter of 20mm, at which time the mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation, lungs collected and fixed for whole mount analysis and tumors bisected and randomly allocated to either fixation in 10% neutral buffered formalin and paraffin embedding or further dissociation for in vitro studies. Animals with illness arising independent of their tumors that required sacrifice prior to the tumor reaching predetermined criteria were excluded from analyses.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Histological analysis was performed for a randomly selected subset of the most advanced tumors (n≥7). H&E stained sections were prepared from Muc4wt/NDL and Muc4ko/NDL tumors using previously described methods42 with analysis of tumor features carried out blinded by a licensed pathologist. Immunohistochemistry was performed essentially as described52 with the substitution of 10% normal goat serum for protein blocking, Bloxall for blocking endogenous peroxidase (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA USA), DAB as the chromogen (Vector) and tris-buffered saline with 0.1% tween as the buffer for phosphorylated antibodies. Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry are listed in Supplemental Table 1. Tumor sections were prepared as an array (n=3 to 4 tumors of the same genotype on a single slide) or as individual tumors from a single source. Where used, staining intensities were scored with the scale: 0=negative, 1=weak, 2=moderate and 3=strong with the accuracy of scoring confirmed by a blinded observer. An internal negative control (no primary antibody) was included with each trial.

Lung Analysis

Lungs were inflated with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), fixed in formalin for 24hrs and stained in carmine alum as described52. Gross lesions were imaged under a dissecting microscope (Zeiss Stemi 2000-C; Axiocam ERc/5s) and further dissected for confirmation by histology. Microlesions were evaluated separately by histology of 4-step serial sections (5μm, n=3) taken at 40-50μm intervals.

Tail Vein Injections

Pooled primary Muc4wt/NDL or Muc4ko/NDL cells (n=4 per genotype; 5 × 105 in 200uL PBS) were instilled under isoflurane anesthesia to the lateral tail vein of 9-week old FvB/NJ female mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). Blood and tissues (lung, liver, spleen, uterus, brain, kidney, digestive tract) were collected 3d (n=4/line) and 28d (n=6/line) later for circulating tumor cell assays and analysis of metastasis, respectively. Mice were randomly assigned to both treatments and time of sacrifice and were caged as mixed cohorts.

Cell Culture

Cells were maintained in DMEM + 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Axenia Biologix, Dixon, CA USA) and penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Waltham, MA USA) at 37°C under 10% CO2 and were were routinely passaged using 0.05% typsin-EDTA (Gibco). Primary NDL tumor cells were dissociated by enzymatic and mechanical methods essentially as described for normal mammary tissue42 from Muc4wt/NDL (n=4) and Muc4ko/NDL (n=4) tumors. Tumor cells were harvested from the most advanced tumor and used within four passages to ensure equal comparison. The expression of Muc4 was retained over this duration, as confirmed by immunocytochemistry (data not shown).

Anoikis assay

Primary NDL cells were plated at a density of 3 × 103 cells/mL in basal media in ultra-low adherence culture plates (Corning, Corning, NY USA) for 24hrs and viability in suspension conditions determined by trypan blue exclusion assay as described43.

Blood cell co-culture suspension assays

Blood was harvested from 8-12 week-old Muc4wt (n=6) or Muc4ko mice (n=6) via cardiac puncture, added to 3.8% sodium citrate (9:1) to prevent clot formation and centrifuged at ~130 × g for 10 min at room temperature. The upper fraction containing plasma, immune cells and platelets (platelet-rich plasma) was re-centrifuged at ~300 × g to separate the cellular and plasma fractions. Blood cells were re-suspended in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Media (IMDM, Gibco)9 with 10% FBS (blood cell fraction; BC), combined with Muc4wt/NDL or Muc4ko/NDL cells at a ratio of 50 to 100:1, and cultured in ultra-low adherence conditions for 24hrs. Controls included IMDM + 10% FBS or IMDM + 10% FBS/cell-free plasma (CFP).

Under ultra-low adherence conditions, NDL cells form small spheroids that are distinguishable from single white or red blood cells. For viability assays, tumor cells were pre-incubated with MitoFluor green (Molecular Probes, Waltham, MA USA) for 30 min prior to co-culture to ensure their later discrimination from blood cells. MitoFluor green label retention was verified to extend beyond 36hrs in NDL cells (data not shown) and was chosen for its capacity to effectively label all cells without adversely affecting viability. Within 30 min prior to concluding co-culture experiments, the entire culture was incubated with the vital nuclear stain Hoechst 33342 (Promokine, Heidelberg, Germany; ex. 350 nm/em. 461nm) to detected nucleated immune and tumor cells, washed gently in PBS to remove unbound dye and stained with ethidium homodimer II (Promokine; ex. 528nm/em. 617nm) to identify dead/dying cells with poor membrane integrity. Non-nucleated platelets remained unstained. Spheres were pipetted onto microscope slides (Thermo), cover slipped and immediately imaged with an Olympus BX51 (Center Valley, PA USA) fluorescence microscope fitted with a Nuance FX CRI camera.

For association assays, pooled NDL cells (n=4/line) and blood cells were monitored and imaged at 1.5hrs and 24hrs on an Olympus IX81 microscope with Olympus cellSens Entry software. Interactions were considered to include the residence of any blood cell within close proximity (≤5μm) to a tumor cell. Time-lapse images of a single field were captured at 1s intervals for 30-40s.

Circulating tumor cell assay

Whole blood (~1mL) was harvested as described above from mice injected at the lateral tail vein 3d prior with pooled NDL cells. Blood was immediately fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2hrs, centrifuged (~300 × g) and washed in PBS. Nuclei were stained with DAPI for 1hr at room temperature, plated on a glass microscope slide in a small volume of PBS and evaluated by fluorescence (tumor cells) and bright field (blood cells) microscopy.

Transwell migration assay

Primary NDL cells were subjected to the transwell migration assay as described49, with some modifications. Cells were plated directly onto the transwell in serum starve media (0.1% FBS) at a density of 2.5 × 104 cells/mL and migration was permitted for 16hrs. Migrated cells were fixed and stained with Diff-Quick staining solution (Dade Behring, Deerfield, IL, USA) prior to imaging with an Olympus IX81.

Statistics, data and image analysis

Values are expressed as means ± standard deviations. For in vitro experiments, data represent at least three biological replicates preformed with a minimum of duplicate technical replicates. Data for in vivo studies reflect means of 4-6 (tail vein assays) or ≥12 mice (genetic studies) per line. Cohorts were based on two-sided power calculations (P=0.05, 80% power) to detect differences in tumor growth/metastasis and are consistent with previous studies1,33. Statistical significance was established using independent two-sided Student’s t-test (with variance assumptions based on F-tests), Mann-Whitney U test (non-linear values- IHC, tumor burden and lung metastases) or log-rank test (survival curves) with P-values less than 0.05 considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed with Microsoft Excel or R-statistical platform. Images were compiled in Adobe Photoshop with brightness, contrast and white balance modified only for clarity in print. Cell counting was performed using image J (NIH; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the histology core facility at UC Davis for embedding services and slide preparation, the UC Davis animal facilities for routine management of mouse colonies, the UC Davis Mouse Biology Program for breeding assistance, and Lakmal Kotelawala, Maxine Umeh-Garcia, and Heather Workman for technical assistance. These studies were supported by NIH grants R01 CA123541 (KLC), R01 CA118384 (CS), and P01 HL110873 (WKO), NIH fellowships and training grants T32 CA108459 (ARRH) and CA165758 (JH), NIH Center grants P30 CA093373 and P30 DK065988, Department of Defense fellowship W81XWH-111-0065 (JHW), and a grant from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation BOUCHE15R0 (WKO).

Financial disclosures:

NIH/NCI: T32 CA108459 (A.R. Rowson-Hodel)

NIH/NCI: F31 CA165758 (J. Hatakeyama)

NIH/NCI: F31 CA210467 (K. VanderVorst)

NIH/NCI: R01 CA166412 (K.L. Carraway, III)

NIH/NCI: R01 CA118384 (C. Sweeney)

NIH/NCI: P30 CA093373 (UCD Cancer Center Support Grant)

NIH/NHLBI: P01 HL110873 (W.K. O’Neal)

NIH/NIDDK: P30 DK065988 (UNC Cystic Fibrosis Center Support Grant)

DoD CDMRP: W81XWH-111-0065 (J.H. Wald)

Cystic Fibrosis Foundation: BOUCHE15R0 (W.K. O’Neal)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Supplemental Information

Supplemental Information accompanies the paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc).

References

- 1.Boimel PJ, Smirnova T, Zhou ZN, Wyckoff J, Park H, Coniglio SJ, et al. Contribution of CXCL12 secretion to invasion of breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Research. 2012;14:R23. doi: 10.1186/bcr3108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borsig L, Wong R, Hynes RO, Varki NM, Varki A. Synergistic effects of L- and P-selectin in facilitating tumor metastasis can involve non-mucin ligands and implicate leukocytes as enhancers of metastasis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:2193–2198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261704098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carraway KL, Rossi EA, Komatsu M, Price-Schiavi SA, Huang D, Guy PM, et al. An Intramembrane Modulator of the ErbB2 Receptor Tyrosine Kinase That Potentiates Neuregulin Signaling. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:5263–5266. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carraway KL, Perez A, Idris N, Jepson S, Arango M, Komatsu M, et al. Muc4/sialomucin complex, the intramembrane ErbB2 ligand, in cancer and epithelia: to protect and to survive. Progress in nucleic acid research and molecular biology. 2002;71:149–185. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(02)71043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers AF, Groom AC, MacDonald IC. Dissemination and growth of cancer cells in metastatic sites. Nature reviews Cancer. 2002;2:563–572. doi: 10.1038/nrc865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaturvedi P, Singh AP, Moniaux N, Senapati S, Chakraborty S, Meza JL, et al. MUC4 mucin potentiates pancreatic tumor cell proliferation, survival, and invasive properties and interferes with its interaction to extracellular matrix proteins. Molecular cancer research: MCR. 2007;5:309–320. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaturvedi P, Singh AP, Batra SK. Structure, evolution, and biology of the MUC4 mucin. The FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2008;22:966–981. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9673rev. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaturvedi P, Singh AP, Chakraborty S, Chauhan SC, Bafna S, Meza JL, et al. MUC4 mucin interacts with and stabilizes the HER2 oncoprotein in human pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer research. 2008:68. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damsgaard CT, Lauritzen L, Calder PC, Kjaer TM, Frokiaer H. Whole-blood culture is a valid low-cost method to measure monocytic cytokines - a comparison of cytokine production in cultures of human whole-blood, mononuclear cells and monocytes. Journal of immunological methods. 2009;340:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fidler IJ. Metastasis: quantitative analysis of distribution and fate of tumor emboli labeled with 125 I-5-iodo-2′-deoxyuridine. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1970;45:773–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujita N, Takagi S. The impact of Aggrus/podoplanin on platelet aggregation and tumour metastasis. Journal of biochemistry. 2012;152:407–413. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvs108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Funes M, Miller JK, Lai C, Carraway KL, 3rd, Sweeney C. The mucin Muc4 potentiates neuregulin signaling by increasing the cell-surface populations of ErbB2 and ErbB3. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:19310–19319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603225200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gay LJ, Felding-Habermann B. Contribution of platelets to tumour metastasis. Nature reviews Cancer. 2011;11:123–134. doi: 10.1038/nrc3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gil-Bernabe AM, Ferjancic S, Tlalka M, Zhao L, Allen PD, Im JH, et al. Recruitment of monocytes/macrophages by tissue factor-mediated coagulation is essential for metastatic cell survival and premetastatic niche establishment in mice. Blood. 2012;119:3164–3175. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-376426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Granot Z, Henke E, Comen EA, King TA, Norton L, Benezra R. Tumor entrained neutrophils inhibit seeding in the premetastatic lung. Cancer cell. 2011;20:300–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guy CT, Webster MA, Schaller M, Parsons TJ, Cardiff RD, Muller WJ. Expression of the neu protooncogene in the mammary epithelium of transgenic mice induces metastatic disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1992;89:10578–10582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauselmann I, Borsig L. Altered tumor-cell glycosylation promotes metastasis. Frontiers in oncology. 2014;4:28. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holbro T, Civenni G, Hynes NE. The ErbB receptors and their role in cancer progression. Experimental cell research. 2003;284:99–110. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu Q, Sun W, Qian C, Wang C, Bomba HN, Gu Z. Anticancer Platelet-Mimicking 528 Nanovehicles. Advanced Materials. 2015;27:7043–7050. doi: 10.1002/adma.201503323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Komatsu M, Carraway CA, Fregien NL, Carraway KL. Reversible disruption of cell-matrix and cell-cell interactions by overexpression of sialomucin complex. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1997;272:33245–33254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.33245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komatsu M, Yee L, Carraway KL. Overexpression of Sialomucin Complex, a Rat Homologue of MUC4, Inhibits Tumor Killing by Lymphokine-activated Killer Cells. Cancer research. 1999;59:2229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komatsu M, Tatum L, Altman NH, Carothers Carraway CA. Carraway KL. Potentiation of metastasis by cell surface sialomucin complex (rat MUC4), a multifunctional anti-adhesive glycoprotein. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2000;87:480–486. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20000815)87:4<480::aid-ijc4>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Komatsu M, Jepson S, Arango ME, Carothers Carraway CA. Carraway KL. Muc4/sialomucin complex, an intramembrane modulator of ErbB2/HER2/Neu, potentiates primary tumor growth and suppresses apoptosis in a xenotransplanted tumor. Oncogene. 2001;20:461–470. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar R, Yarmand-Bagheri R. The role of HER2 in angiogenesis. Seminars in oncology. 2001;28:27–32. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Labelle M, Hynes RO. The initial hours of metastasis: the importance of cooperative host-tumor cell interactions during hematogenous dissemination. Cancer discovery. 2012;2:1091–1099. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J, Ai Y, Wang L, Bu P, Sharkey CC, Wu Q, et al. Targeted drug delivery to circulating tumor cells via platelet membrane-functionalized particles. Biomaterials. 2016;76:52–65. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, Sharkey CC, Wun B, Liesveld JL, King MR. Genetic engineering of platelets to neutralize circulating tumor cells. Journal of controlled release: official journal of the Controlled Release Society. 2016;228:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lorusso G, Rüegg C. New insights into the mechanisms of organ-specific breast cancer metastasis. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2012;22:226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lundmark A, Davanian H, Båge T, Johannsen G, Koro C, Lundeberg J, et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals mucin 4 to be highly associated with periodontitis and identifies pleckstrin as a link to systemic diseases. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:18475. doi: 10.1038/srep18475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mehlen P, Puisieux A. Metastasis: a question of life or death. Nature reviews Cancer. 2006;6:449–458. doi: 10.1038/nrc1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitjavila-Garcia MT, Cailleret M, Godin I, Nogueira MM, Cohen-Solal K, Schiavon V, et al. Expression of CD41 on hematopoietic progenitors derived from embryonic hematopoietic cells. Development. 2002;129:2003–2013. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moasser MM. The oncogene HER2; Its signaling and transforming functions and its role in human cancer pathogenesis. Oncogene. 2007;26:6469–6487. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohanty S, Xu L. Experimental Metastasis Assay. 2010:e1942. doi: 10.3791/1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen DX, Bos PD, Massague J. Metastasis: from dissemination to organ-specific colonization. Nature reviews Cancer. 2009;9:274–284. doi: 10.1038/nrc2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olsson A-K, Dimberg A, Kreuger J, Claesson-Welsh L. VEGF receptor signalling in control of vascular function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:359–371. doi: 10.1038/nrm1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park J, Wysocki RW, Amoozgar Z, Maiorino L, Fein MR, Jorns J, et al. Cancer cells induce metastasis-supporting neutrophil extracellular DNA traps. Science Translational Medicine. 2016;8:361ra138. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ponnusamy MP, Singh AP, Jain M, Chakraborty S, Moniaux N, Batra SK. MUC4 activates HER2 signalling and enhances the motility of human ovarian cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2008;99 doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ponnusamy MP, Lakshmanan I, Jain M, Das S, Chakraborty S, Dey P, et al. MUC4 mucin-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition: a novel mechanism for metastasis of human ovarian cancer cells. Oncogene. 2010;29:5741–5754. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ponnusamy MP, Seshacharyulu P, Vaz A, Dey P, Batra SK. MUC4 stabilizes HER2 expression and maintains the cancer stem cell population in ovarian cancer cells. Journal of Ovarian Research. 2011;4:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qian B, Deng Y, Im JH, Muschel RJ, Zou Y, Li J, et al. A distinct macrophage population mediates metastatic breast cancer cell extravasation, establishment and growth. PloS one. 2009;4:e6562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rachagani S, Macha MA, Ponnusamy MP, Haridas D, Kaur S, Jain M, et al. MUC4 potentiates invasion and metastasis of pancreatic cancer cells through stabilization of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1953–1964. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rowson-Hodel AR, Manjarin R, Trott JF, Cardiff RD, Borowsky AD, Hovey RC. Neoplastic transformation of porcine mammary epithelial cells in vitro and tumor formation in vivo. BMC cancer. 2015;15:562. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1572-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rowson-Hodel AR, Berg AL, Wald JH, Hatakeyama J, VanderVorst K, Curiel DA, et al. Hexamethylene amiloride engages a novel reactive oxygen species- and lysosome-dependent programmed necrotic mechanism to selectively target breast cancer cells. Cancer letters. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Senapati S, Chaturvedi P, Chaney WG, Chakraborty S, Gnanapragassam VS, Sasson AR, et al. Novel INTeraction of MUC4 and galectin: potential pathobiological implications for metastasis in lethal pancreatic cancer. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17:267–274. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siegel PM, Ryan ED, Cardiff RD, Muller WJ. Elevated expression of activated forms of Neu/ErbB-2 and ErbB-3 are involved in the induction of mammary tumors in transgenic mice: implications for human breast cancer. The EMBO Journal. 1999;18:2149–2164. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh AP, Moniaux N, Chauhan SC, Meza JL, Batra SK. Inhibition of MUC4 expression suppresses pancreatic tumor cell growth and metastasis. Cancer research. 2004;64:622–630. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh PK, Hollingsworth MA. Cell surface-associated mucins in signal transduction. Trends in cell biology. 2006;16:467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan M, Yao J, Yu D. Overexpression of the c-erbB-2 gene enhanced intrinsic metastasis potential in human breast cancer cells without increasing their transformation abilities. Cancer research. 1997;57:1199–1205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wald JH, Hatakeyama J, Printsev I, Cuevas A, Fry WHD, Saldana MJ, et al. Suppression of planar cell polarity signaling and migration in glioblastoma by Nrdp1-mediated Dvl polyubiquitination. Oncogene. 2017 doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Workman HC, Miller JK, Ingalla EQ, Kaur RP, Yamamoto DI, Beckett LA, et al. The membrane mucin MUC4 is elevated in breast tumor lymph node metastases relative to matched primary tumors and confers aggressive properties to breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Research: BCR. 2009;11:R70–R70. doi: 10.1186/bcr2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Workman HC, Sweeney C, Carraway KL. The Membrane Mucin Muc4 Inhibits Apoptosis Induced by Multiple Insults via ErbB2-Dependent and ErbB2-Independent Mechanisms. Cancer research. 2009;69:2845–2852. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yokdang N, Hatakeyama J, Wald JH, Simion C, Tellez JD, Chang DZ, et al. LRIG1 opposes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and inhibits invasion of basal-like breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2016;35:2932–2947. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang J, Perez A, Yasin M, Soto P, Rong M, Theodoropoulos G, et al. Presence of MUC4 in human milk and at the luminal surfaces of blood vessels. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2005;204:166–177. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang J, Carraway CA, Carraway KL. Muc4 expression during blood vessel formation in damaged rat cornea. Current eye research. 2006;31:1011–1014. doi: 10.1080/02713680601052155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao Q, Barclay M, Hilkens J, Guo X, Barrow H, Rhodes JM, et al. Interaction between circulating galectin-3 and cancer-associated MUC1 enhances tumour cell homotypic aggregation and prevents anoikis. Molecular cancer. 2010;9:154. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhi X, Tao J, Xie K, Zhu Y, Li Z, Tang J, et al. MUC4-induced nuclear translocation of beta-catenin: a novel mechanism for growth, metastasis and angiogenesis in pancreatic cancer. Cancer letters. 2014;346:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.