Abstract

Background and aims

Millions of people worldwide use websites to help them quit smoking, but effectiveness trials have an average 34% follow-up data retention rate and an average 9% quit rate. We compared the quit rates of a website using a new behavioral approach called Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; WebQuit.org) with the current standard of the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Smokefree.gov website.

Design

A two-arm stratified double-blind individually randomized trial (n = 1319 for WebQuit; n = 1318 for Smokefree.gov) with 12-month follow-up.

Setting

USA.

Participants

Adults (N = 2637) who currently smoked at least 5 cigarettes per day were recruited from March 2014 to August 2015. At baseline, participants were mean (SD) age of 46.2 (13.4), 79% women, and 73% white.

Interventions

WebQuit.org website (experimental) provided ACT for smoking cessation; Smokefree.gov website (comparison) followed US Clinical Practice Guidelines for smoking cessation.

Measurements

The primary outcome was self-reported 30-day point prevalence abstinence at 12 months.

Findings

The 12-month follow-up data retention rate was 88% (2309/2637). The 30-day point prevalence abstinence rates at the 12-month follow-up were 24% (278/1141) for WebQuit.org and 26% (305/1168) for Smokefree.gov (OR = 0.91; 95% CI = 0.76, 1.10); p = 0.334) in the a priori complete case analysis. Abstinence rates were 21% (278/1319) for WebQuit.org and 23% (305/1318) for Smokefree.gov (OR = 0.89 (0.74, 1.07); p = 0.200) when missing cases were imputed as smokers. The Bayes Factor comparing the primary abstinence outcome was 0.17, indicating “substantial” evidence of no difference between groups.

Conclusions

WebQuit.org and Smokefree.gov had similar 30-day point prevalence abstinence rates at 12 months that were descriptively higher than those of prior published website-delivered interventions and telephone counselor-delivered interventions.

Keywords: tobacco cessation, websites, mindfulness, acceptance and commitment therapy

Introduction

Worldwide, tobacco smoking is the second leading cause of early death and disability (1), attributable to over one in ten deaths (2). Barriers to accessing smoking cessation treatments include low reimbursement for providers and low consumer demand for traditional treatments (3). Fortunately, website-delivered interventions provide cessation assistance with high population-level reach (4). Seventy-nine percent of US smokers use the Internet (5). Eleven million US smokers each year, and many millions more worldwide, use websites to help them quit smoking (5). Compared to telephone quitline interventions, website interventions have: (1) at least 21 times higher overall national reach [11 million for web vs. 500,000 for quitlines (5),(6)], and (2) lower cost-per-quit [e.g., $291 for web vs. $1850 for quitlines (7)].

Web-delivered cessation interventions have existed for over twenty-five years (8). However, few randomized trials have tested these websites with long term follow-up, which is critical because of the high level of relapse that occurs by 12 months (8, 9). These trials have weighted average 12-month follow-up data retention rates of 34% (range: 11% to 72%). Follow-up rates below 80% can seriously threaten validity (10).

The weighted average 12-month 30-day point prevalence cessation rate for previous web-delivered intervention trials was 9% [range: 7% to 17% (8, 9)]. While 9% is higher than the 4% success rate from quitting on one’s own, it is much lower than the 14% weighted average success rate of telephone quitlines (11). Thus, web-delivered interventions have great room for improvement (4, 9). Overall, there is need for rigorous randomized trials of web-based cessation interventions with long-term follow-up, with potential for high population-level impact.

To address these needs, we compared two conceptually distinct websites for smoking cessation. The first was an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (12) (ACT) website called “WebQuit.” ACT is a new approach that teaches skills for allowing urges to smoke pass without smoking, which is conceptually distinct from US Clinical Practice Guidelines (USCPG)-based standard of care approaches that teach avoidance of urges. WebQuit motivates smokers to quit by appealing to their values whereas the USCPG-based standard approaches motivate using reason and logic. The ACT approach has demonstrated initial feasibility and usefulness for smoking cessation across a variety of delivery modalities (13, 14).

The second website, Smokefree.gov (“Smokefree”), provides the nation’s current standard of care for web-delivered smoking cessation in that: (a) its content follows USCPG (15),(b) it is the most accessed cessation website in the world (3.6 million visits in 2016 [Erik Augustson, April 21, 2017, personal communication]), and (c) it has the highest user satisfaction rates of all non-profit websites for smoking cessation (16, 17). In a pilot randomized trial, both websites showed promising 3-month follow-up quit rates (14), and Smokefree has since shown promising 7-month quit rates (17).

This article presents the outcomes of a full-scale randomized trial comparing WebQuit with Smokefree on:

30 day point prevalence abstinence (PPA) at 12-month follow-up (hypothesis: WebQuit will have higher abstinence rates than Smokefree);

acceptance of cravings and whether changes in acceptance of cravings prospectively predicted abstinence;

participant engagement and satisfaction.

Methods

Design

The study was a two-arm randomized controlled trial comparing WebQuit with Smokefree. Participants were recruited online, stratified randomized (to avoid chance bias), and surveyed at 12 months, with interim surveys at 3 and 6 months. The 12-month primary endpoint accounted for the high levels relapse rates that occur by 12 months (18, 19) and is directly comparable to the most rigorous trials of web-delivered smoking cessation (8, 9). Based on the 3-month quit rates observed in our previous pilot trial (14) and relapse rates occurring between 3 and 12 months after randomization (18, 19), the study was 80% powered for a two-tailed significant difference between a 14.8% WebQuit quit rate and a 10.3% Smokefree quit rate.

Procedures

Participants & Enrollment

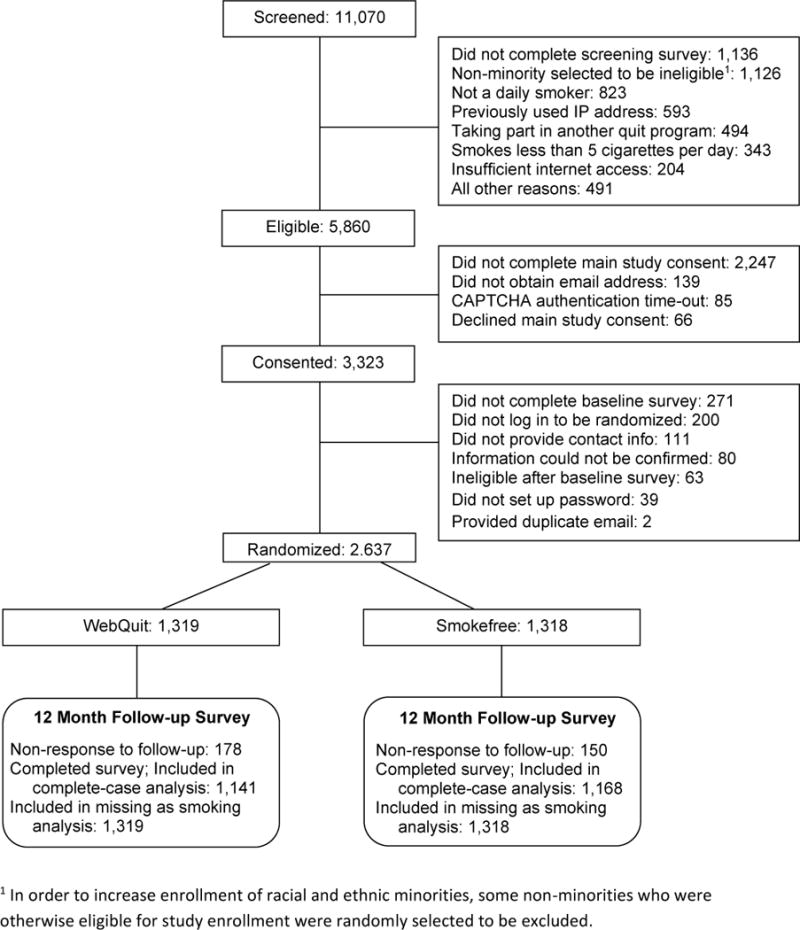

Adult smokers (n = 2637) were recruited March 2014 to August 2015. The study participant flow diagram is shown in Figure 1. Smokers were recruited nationally via targeted Facebook ads, an online survey panel, search engine results, friends/family referral, Google ads, and earned media. The eligibility criteria were: age 18 or older; smoked ≥ 5 cigarettes a day for the last year; ready to quit in the next 30 days; lived in the United States; could read English; access to Internet and email; never used Smokefree.gov and were not currently using other cessation treatment; never participated in our prior studies; no household members already enrolled; and willing to be randomized to treatment, to complete three surveys, and to provide contact information for themselves and two relatives. Some advertisements were targeted to minorities and enrollment was limited to no more than 75% Caucasian participants, to ensure minority representation.

Figure 1.

Participant Flow Diagram

Participants completed a web-based screening survey and were notified of their eligibility via email. Participants who clicked on their emailed link were returned to the study website where they provided consent, completed a baseline survey, completed a contact form, and activated the automated randomization algorithm. At each enrollment step, the study was presented as a comparison of “two web-delivered smoking cessation programs.”

Since enrollment occurred online, additional actions were taken to ensure enrollees were actually eligible. These included CAPTCHA authentication, review of IP addresses for duplicates or non-US origin, and review of survey logs for suspicious response times (< 90 seconds to complete screening or < 10 minutes to complete baseline survey). Suspicious cases were contacted by staff. If their information could not be confirmed (n = 80), they were not enrolled.

All study activities were reviewed and approved by the participating sites’ Institutional Review Boards.

Randomization

Participants were randomized (1:1) to either the experimental intervention (WebQuit.org, n=1319) or the control intervention (Smokefree.gov, n=1318). Using randomly permuted block randomization, stratified by daily smoking frequency (≤20 vs. ≥ 21), education (≤ high school vs. ≥ some college), and gender (male vs. female). Random assignments were concealed from participants until after study eligibility, consent, and baseline data was obtained. Neither research staff nor study participants had access to upcoming randomized study arm assignments.

Blinding & Contamination

To ensure participants were blinded to their assigned intervention, each website was branded as “WebQuit” and neither mentioned ACT or Smokefree.gov. Contamination between sites was avoided with a unique user name and password provided only to the individual user and by having an eligibility criterion of not having family, friends, or other household members participating.

Follow-up Assessment

Participants completed follow-up surveys at 3, 6, and 12 months post-randomization. Participants received $25 for completing each survey and an additional $10 bonus if the online survey was completed within 24 hours of initial email invitation to take the survey. Persons who did not complete the survey online were sequentially offered opportunities to do so by phone, mailed survey, and then, for main outcomes only, by postcard.

Interventions

WebQuit

WebQuit covered the six core processes in ACT— Values, Committed Action, Willingness, Being Present, Cognitive Defusion, and Self-as-Context. The program had four parts. Step 1, Make a Plan, allowed users develop a personalized quit plan, identify smoking triggers, learn about FDA-approved cessation medications, and upload a photo of their inspiration to quit (ACT processes: Values and Committed Action). Step 2, Be Aware, contained three exercises to illustrate the problems with trying to control thoughts, feelings and physical sensations rather than allowing them to come and go (ACT process: Creative Hopelessness). Step 3, Be Willing, contained eight exercises to help users practice allowing thoughts, feelings and physical sensations that trigger smoking (ACT processes: Willingness, Being Present, and Cognitive Defusion). Step 4, Be Inspired, contained 15 exercises to help participants identify deeply-held values inspiring them to quit smoking and to exercise self-compassion in response to smoking lapses (ACT processes: Values and Self-as-Context). The program also prompted users to track smoking, cessation medications, and practice of ACT skills. Tracking results were displayed graphically along with the user’s inspiration for quitting and badges earned for program use. The website contained a forum for asking questions about quitting and anytime tips (e.g., a list of tips for dealing with other smokers).

Smokefree

We hosted a secured private version of the Smokefree site. Users were able to navigate through all pages of the website at any time and there were no restrictions on the order in which the content could be viewed. Smokefree had three main sections: “Quit today,” “Preparing to quit,” and “Smoking issues”. The “Quit today” section had seven pages of content that provide tips for the quit day, staying smoke-free, and dealing with cravings. The section also provided information on withdrawal, benefits of quitting, and FDA-approved cessation medications. The “Prepare to quit” section had seven content pages providing information on various reasons to quit, what makes quitting difficult, how to make a quit plan, and using social support during a quit attempt. The “Smoking issues” section provided five pages on health effects of smoking and quitting, depression, stress, secondhand smoke, and coping with the challenges of quitting smoking for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community. The section also contained five quizzes that provided feedback about level of depression, stress, nicotine dependence, nicotine withdrawal, and secondhand smoke as well as tips for coping with them.

Both interventions were available for login anytime for 12 months after randomization. Neither was modified during the course of the study. For 28 days after randomization, participants in both arms were sent via text or email (their choice) up to four daily messages (≤ 160 characters) designed to encourage logging in, unless they opted out.

Measures

Baseline measures

At baseline, participants reported on demographics, mental health measures, alcohol use, and smoking in their social environment, such as whether they currently lived with a partner who smokes and the number of close friends who smoke regularly. Mental health measures included depression [CES-D (20)], generalized anxiety [GAD-7 (21)], panic disorder [ANSQ (22)], post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [PCL-6 (23)], and social anxiety [mini-SPIN (24)].

Nicotine dependence

Nicotine dependence was measured with the six-item Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence [FTND (25)] at baseline and 12-month follow up.

ACT theory-based acceptance process

At baseline and three-month follow-up, willingness to experience and not act on cravings to smoke (i.e., acceptance) was measured using a nine-item physical sensations subscale of the Avoidance and Inflexibility Scale [adapted from (26, 27)]. Response choices for each item ranged from “Not at all” (1) to “Very willing” (5). Scores were derived by averaging the items.

Main outcome

For direct comparability with the most rigorous internet-based randomized trials to date (8), the primary outcome of the study was complete case 30-day point prevalence abstinence (PPA; i.e., no smoking at all in the past 30 days) at 12-month follow-up. Due to low demand characteristics for false reporting, the SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification recommended biochemical confirmation is unnecessary in population-based studies with no face-to-face contact and studies where data are optimally collected through the web, telephone, or mail (28). Self-reported smoking is a standard method for assessing the efficacy of web-delivered interventions (8, 9). Therefore, smoking status was the self-reported response to the question “When was the last time you smoked, or even tried, a cigarette?”

Secondary outcomes

Secondary cessation outcomes

Imputed missing=smoking 30-day PPA, complete case 7-day PPA, and imputed missing=smoking 7-day PPA.

Engagement outcomes

Measures of website engagement were collected for 12 months after randomization. The number of times a participant logged in, length of use of the website from first to last login in days, time spent on each session in minutes, number of web pages visited per login, and time spent on each web page in minutes were calculated from data automatically logged by the secured server. Any user activity occurring more than 15 minutes from the previous activity was considered a new login. Participants in the top 25% of number of logins for their assigned website were considered “high engagers.”

Treatment satisfaction outcomes

Treatment satisfaction outcomes were extent to which: (1) assigned website was useful for quitting, (2) user was satisfied with assigned website, and (3) user would recommend assigned website to friend. Example item: “Would you recommend your assigned website to a friend?” Response choices for all items ranged from “Not at all” (1) to “Very much” (5) and were dichotomized at a threshold of “Somewhat” (3) or higher.

Statistical analyses

Specified a priori as the primary outcome was the 12-month follow-up 30-day point prevalence abstinence using a complete case analysis in which those who did not provide follow-up data were excluded. As secondary outcomes, 30-day and 7- day PPA abstinence were also examined among all enrolled participants with missing cases imputed as smokers, and complete case 7-day PPA was also examined. While some research suggests that missing=smoking outcomes may be biased (29, 30), they are recommended by the Russell Standard (31), allow for comparison of results with prior web-delivered intervention trials, and provide a sensitivity analysis. We used logistic regression models for the cessation outcome as well as secondary binary outcomes related to cessation and treatment satisfaction. Negative binomial models were used to assess differences between treatment arms for zero-inflated count outcomes (e.g., number of logins), while generalized linear models were used for continuous outcomes. We controlled for multiple comparisons in all secondary and subgroup analyses using the Holm procedure (32). We evaluated the Bayes factor for the primary cessation outcome to provide a summary of the presence and magnitude of the treatment effect (33, 34). All statistical tests were two-sided, with α=0.05, and analyses were completed using R 3.3.0 (35) and R packages ‘BayesFactor’ (36) and ‘MASS’ (37).

Baseline balance and covariate adjustment

Baseline characteristics were balanced between treatment groups, except that the WebQuit arm had slightly more married participants than the Smokefree arm (39% vs. 35%, p=.040). However, marital status was not associated with cessation outcomes so was not included as a covariate. We adjusted for the three stratification variables used in randomization to avoid losing power and obtaining incorrect confidence intervals (38).

Results

Participant characteristics

Participant baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Overall, these characteristics were very similar to those of prior published web-delivered smoking intervention trials (8, 9).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics, mental health, and smoking behavior.

| Total (n=2,637) | Smokefree (n=1,318) | WebQuit (n=1,319) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 46.2 (13.4) | 46.1 (13.3) | 46.2 (13.4) |

| Male | 21% | 21% | 21% |

| Caucasian | 73% | 72% | 73% |

| African American | 11% | 11% | 10% |

| Asian | 2% | 2% | 2% |

| Native American or Alaska Native | 2% | 2% | 2% |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | <1% | <1% | 1% |

| More than one race | 5% | 5% | 4% |

| Hispanic | 8% | 9% | 8% |

| Married | 37% | 35% | 39% |

| Working | 52% | 52% | 53% |

| HS or less education | 28% | 28% | 28% |

| LGBT | 10% | 10% | 9% |

| Mental Health | |||

| Current depression symptoms (CES-D >=16) | 56%, n=2622 | 56%, n=1309 | 56%, n=1313 |

| Current anxiety symptoms (GAD-7 >=10) | 34%, n=2623 | 35%, n=1316 | 34%, n=1307 |

| Current panic disorder symptoms (ANSQ >1) | 48%, n=2364 | 49%, n=1187 | 48%, n=1177 |

| Current PTSD symptoms (PCL-6 >=14) | 53%, n=26 | 53%, n=1316 | 53%, n=1312 |

| Current social anxiety symptoms (mini-SPIN >=6) | 30%, n=2630 | 31%, n=1315 | 30%, n=1315 |

| Smoking Behavior | |||

| FTND score, mean (SD) | 5.6 (2.2) | 5.6 (2.2) | 5.6 (2.2) |

| High nicotine dependence (FTND >=6) | 55% | 55% | 54% |

| Smokes more than half pack per day | 79% | 79% | 79% |

| Smokes more than one pack per day | 33% | 33% | 33% |

| First cigarette within 5 minutes of waking | 41% | 41% | 42% |

| Smoked for 10 or more years | 80% | 80% | 80% |

| Used e-cigarettes at least once in past month | 34% | 34% | 34% |

| Quit attempts in past 12M, mean (SD) | 1.6 (5.0), n=2511 | 1.6 (4.6), n=1270 | 1.6 (5.3), n=1241 |

| At least one quit attempt in past 12M | 45%, n=2511 | 46%, n=1270 | 43%, n=1241 |

| Commitment to quitting | 4.0 (0.8), n=2628 | 4.0 (0.8), n=1316 | 4.0 (0.7), n=1312 |

| Friend & Partner Smoking | |||

| Close friends who smoke, mean (SD) | 2.2 (1.6) | 2.2 (1.6) | 2.2 (1.6) |

| Number of adults in home who smoke, mean (SD) | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.8) |

| Living with partner who smokes | 30% | 29% | 30% |

| ACT Theory-Based Measure, mean (SD) | |||

| Acceptance of physical triggers | 2.93 (0.47), n=2603 | 2.93 (0.48), n=1302 | 2.93 (0.47), n=1301 |

| Alcohol Use | |||

| Heavy drinker | 11%, n=2573 | 11%, n=1285 | 11%, n=1288 |

Participant retention

The data retention rate was 88% (2309/2637) and did not differ between arms (WebQuit: 87% (1141/1319); Smokefree: 89% (1168/1318); OR=0.82 (0.65, 1.04), p=.096). Participants completed the 12-month follow-up survey via web (92% of respondents), telephone (3%), mail (3%), and by postcard short survey of primary and selected secondary outcomes (2%). Sixty five percent of those who completed the survey did so within 24 hours of receiving the email invitation that noted the $10 bonus incentive.

Primary cessation outcome

The 30-day PPA rates at the one-year follow-up were 24% for WebQuit.org and 26% for Smokefree.gov (Table 2). The Bayes Factor for the primary abstinence outcome was 0.17, indicating “substantial” evidence for the null hypothesis of no difference between groups ((39)).

Table 2.

Smoking cessation outcomes at 12-month follow-up.

| Outcome Variable | Overall (n=2637) | Smokefree (n=1318) | WebQuit (n=1319) | OR (95% CI)3 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-day PPA, complete case1, n (%) | 583 (25%), n=2309 | 305 (26%), n=1168 | 278 (24%), n=1141 | 0.91 (0.76, 1.10) | 0.334 |

| 30-day PPA, missing=smoking2, n (%) | 583 (22%) | 305 (23%) | 278 (21%) | 0.89 (0.74, 1.07) | 0.200 |

| 7-day PPA, complete case, n (%) | 709 (31%), n=2309 | 369 (32%), n=1168 | 340 (30%)., n=1141 | 0.92 (0.77, 1.10) | 0.393 |

| 7-day PPA, missing=smoking, n (%) | 709 (27%) | 369 (28%) | 340 (26%) | 0.89 (0.75, 1.06) | 0.393 |

Complete case analysis (i.e., exclusion of participants lost to follow-up) was specified a priori as the primary outcome.

The missing=smoking outcomes are provided as recommended by the Russell Standard.

Odds ratios are adjusted for the three factors used in stratified randomization: daily smoking frequency, education, and gender.

Secondary outcomes

The missing=smoking 30-day PPA rate at the 12-month follow-up was 21% for WebQuit and 23% for Smokefree. The complete case 7-day PPA rate at the 12-month follow-up was 30% (missing=smoking rate: 26%) for WebQuit, as compared to the 32% (missing=smoking rate: 28%) abstinence rate for Smokefree. Further secondary outcomes are available in the Supplementary Table.

Among high engagers, the 30-day PPA rate at the 12-month follow-up was 30% for each website. In addition, the two arms’ 30-day PPA rates did not differ by race/ethnicity, gender, education level, age, employment status, sexual orientation, baseline depression or anxiety, smoking history, baseline friend and partner smoking, baseline acceptance of cravings, or other baseline variable in Table 1 (all p>.050).

Among those who were highly engaged with their website, WebQuit participants had a higher increase in acceptance of cravings to smoke than Smokefree participants (0.19 vs. 0.08 increase; p=0.034). Each one-unit increase, from baseline to 3-month follow-up, in the acceptance of cravings score was strongly associated with 30-day PPA at 12-month follow-up among all participants (OR=4.11; 95% CI=3.40–4.97).

Utilization & Satisfaction

As shown in Table 3, compared to Smokefree, WebQuit participants had a higher: (1) average number of logins, (2) average time spent on each login session, and (3) average number of web pages visited per login. The average length of website usage was the same in both programs at 57 days. Participants in both arms reported high satisfaction with their assigned website, though satisfaction was somewhat higher in the WebQuit arm. For example, 95% of WebQuit participants would recommend the website to a friend, compared to 90% for Smokefree.

Table 3.

Treatment engagement and satisfaction. All items were assessed at 12-month follow-up, with the exception of the last two, satisfaction and recommendation, which were assessed at 3-month follow-up.

| Variable | Overall (n=2637) | Smokefree (n=1318) | WebQuit (n=1319) | OR, IRR, or point estimate (95% CI)1 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of times logged in, mean (SD) | 7.2 (22.8), median=3 | 5.1 (11.9), median=3 | 9.2 (29.9), median=3 | 1.79 (1.64, 1.96) | <0.0001 |

| High engagers (>=5 logins CBT, >=7 ACT), n (%) | 757 (29%) | 401 (30%) | 356 (27%) | 0.84 (0.91, 1.00) | 0.180 |

| Length of use of website in days, mean (SD) | 57 (84), median=21 | 57 (84), median=22 | 57 (84), median=19 | 1.00 (0.89, 1.12) | 0.988 |

| Time spent on each session (minutes), mean (SD) | 5.6 (6.1), n=2624 | 3.6 (4.1), n=1309 | 7.6 (7.1), n=1315 | 4.0 (3.6, 4.5) | <0.0001 |

| Number of web pages visited per login, mean (SD) | 4.5 (3.5), n=2624 | 3.1 (3.1), n=1309 | 5.8 (3.4), n=1315 | 2.8 (2.5, 3.0) | <0.0001 |

| Time spent on each web page (minutes), mean (SD) | 1.1 (0.9), n=2345 | 1.4 (1.2), n=1245 | 0.9 (0.6), n=1245 | -0.44 (-0.51, -0.36) | <0.0001 |

| Website was useful for quitting, n (%) | 1448 (69%), n=2099 | 719 (67%), n=1067 | 729 (71%), n=1032 | 1.16 (0.96, 1.40) | 0.227 |

| Satisfied with assigned website, n (%) | 1681 (81%), n=2068 | 846 (80%), n=1063 | 835 (83%), n=1005 | 1.26 (1.01, 1.57) | 0.180 |

| Would recommend assigned website, n (%) | 1703 (93%), n=1839 | 846 (90%), n=936 | 857 (95%), n=903 | 2.00 (1.38, 2.89) | 0.001 |

OR indicates odds ratio in logistic regression for binary variables, IRR indicates incident rate ratio in negative binomial regression for count variables (i.e., number of times logged in and length of use of website), and point estimate indicates difference between treatment arms for continuous variables. Results are adjusted for the three factors used in stratified randomization: daily smoking frequency, education, and gender.

Discussion

To overcome limitations of prior trials of web-delivered cessation interventions, we conducted a trial comparing the quit rates of a website using a new approach called Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; WebQuit.org) with the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Smokefree.gov website for cessation. Twelve-month, 30-day point prevalence quit rates were high in both arms (26% for Smokefree; 24% for WebQuit). These quit rates were nearly three times higher than the 9% quit rates obtained in prior web-based randomized trials with at least 12-month follow-up (8). Moreover, the quit rates were over one and a half times higher than the 14% quit rates obtained in prior randomized trials of telephone interventions with at least 12-month follow-up [range: 8 -20% (11)].

Quit rates

Comparing the pilot trial (14) with the current full-scale trial, one pattern of results is striking: the WebQuit abstinence rate stayed about the same (23% three-month 30-day quit rate in the pilot compared to 24% 12-month 30-day quit rate in the current trial) while the Smokefree abstinence rate over doubled (10% three-month 30-day quit rate in the pilot compared to 26% in the current trial). This increase was potentially due to the study design of the pilot (14) vs. the current study: the pilot trial had a smaller sample size (222 vs. 2637) and lower retention rate (54% vs. 88%), thus making the point estimate of the pilot less reliable (14). Other reasons might be the synergistic effect of Smokefree content and design revisions that NCI made before the start of the current trial, includign: (1) a front page feature called “I’m craving cigarettes” that provided advice on how to cope with cravings; (2) a front page feature called “I feel depressed” that provided advice on how to cope with depressive symptoms; (3) an interactive feature for selecting pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation, including comparisons of efficacy, cost, and side effects; (4) graphical interactive feature for viewing health effects of smoking and quitting; (5) improved site navigability and page layout.

Engagement and satisfaction

Participants were more engaged with WebQuit than Smokefree and were slightly more satisfied than Smokefree participants. High engagers had higher quit rates and, in general, engagement in web-delivered programs is a well-known predictor of cessation (40). There are a variety of potential reasons why WebQuit users were more engaged. First, participants may have found the ACT content novel and thought provoking. To support this possibility, in qualitative data from the outcome survey, participants made comments such as, “I especially liked the advice to ride with the urges to smoke rather than to try to ignore them or replace them with diversion.” Additionally, WebQuit was a structured program with its main content funneling users in a logical order, and evidence suggests that funneling improves engagement (41, 42).

Implications for ACT research

The current study provides the largest randomized trial of ACT conduced to date. As of May 2017, there were 175 published peer-reviewed randomized controlled trials of ACT, focusing on a variety of outcomes including weight loss and pain management (43). Of these, 22% had a sample size of ≥ 100 [n=39 (43)], 3% had ≥ 300 participants [n=6 (43)], with the largest having 586 participants (44). Of the trials with ≥ 300 participants, the average follow-up length was 8 months, and the average retention rate was 60%. Similar to prior ACT trials, the current trial shows that ACT increases acceptance of internal experiences (e.g., cravings) among those who engage with the content and this acceptance in turn has a strong positive impact on clinical outcomes. The theoretical premise of the ACT model is therefore supported. As to why increased acceptance in the ACT arm did not translate into quit rates higher than the control, we speculate that the control arm had unique theoretical processes that positively and equally impacted its quit rate relative to the ACT arm. Overall, the current study provides a methodologically robust contribution to the ACT scientific literature, and suggests that the ACT model is a reasonable alternative to mainstream approaches to smoking cessation.

Strengths

This study has a number of strengths, including a large sample and long-term follow-up. Most notably, the trial’s 88% 12-month outcome retention rate contributes to confidence in the study findings. Several design factors are believed to contribute to the high retention rate: (1) $25 cash for completing the outcome surveys, (2) $10 bonus cash for completing the web-based survey within 24 hours, and (3) having four methods (web, telephone, mail, and post card) to complete the survey that were offered in sequence (instead of in parallel which is known to reduce overall response rate (45)]. This 88% retention was over 2.5 times higher than the average rate (34%) obtained in prior trials with at least 12-month follow-up (8, 9).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, cessation outcome data were self-reported for reasons stated in the Methods. Remote biochemical validation of smoking cessation would have introduced biases including low response rates, challenges with confirming the identity of the person providing the sample, inability to confirm abstinence beyond 24 hours, and false positive errors due to secondhand smoke. Second, without a third minimal treatment arm (e.g., print-based self-help material), it is possible that observed quit rates would have been achieved with little intervention if participants were highly motivated to quit. However, we think that is highly unlikely for several reasons: (1) the inclusion criteria, recruitment methods, and baseline characteristics of the sample were very similar to prior trials with at least 12-month follow-up (8); (2) smoking cessation self-help materials have low (6%) quit rates (46); and (3) users’ baseline motivation to quit was very similar to other trials of web-delivered smoking cessation (8, 9). For these reasons, we considered and then rejected the idea of a minimal intervention third arm when planning the trial. Third, only 23.8% (2637/11070) of those screened were randomized into the trial. This level of selection bias is highly consistent with prior published web-delivered smoking intervention trials (8, 9) and with prior telephone-delivered cessation intervention trials (11). Indeed, in one of the largest randomized trials of telephone-delivered smoking cessation (47), only 18.5% of those screened were randomized (4614/24089). Note also that the allocation sequence was concealed from investigators and, the inclusion criteria, recruitment methods, and baseline characteristics were very similar to prior web-delivered cessation trials (9). Loss to follow-up is another potential source of bias; however, because retention rates were high and did not vary between arms, and because the missing=smoking analysis led to a similar conclusion as complete case analysis, this potential bias was minimized.

Conclusion

This trial identified two websites that obtained 12-month quit rates higher than any prior published website- or telephone counselor-delivered intervention trial for smoking cessation. To illustrate the potential public health impact, consider that impact is a product of reach and efficacy (48). The projection derived from the current research trial’s conditions is that for every 1 million smokers reached with either website, at least 240,000 would quit smoking. Both websites are helpful options for people seeking online help quitting smoking.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

National Cancer Institute (R01 CA166646; R01CA192849); National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA038411). Funders had no role in the trail conduct or interpretation of results.

Footnotes

Declarations: In July 2016, Dr. Jonathan Bricker was a consultant to Glaxo Smith Kline, the makers of a nicotine replacement therapy. He now serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of Chrono Therapeutics, the makers of a nicotine replacement therapy device. Other authors have no declarations.

Clinical Trials.gov Registration Number: NCT01812278

References

- 1.Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1659–724. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30819-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Husten CG. A Call for ACTTION: Increasing access to tobacco-use treatment in our nation. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(3 Suppl):S414–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Civljak M, Sheikh A, Stead LF, Car J. Internet-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;9:CD007078. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007078.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borrelli B, Bartlett YK, Tooley E, Armitage CJ, Wearden A. Prevalence and Frequency of mHealth and eHealth Use Among US and UK Smokers and Differences by Motivation to Quit. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(7):e164. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Consortium NAQ. Results from the 2012 NAQC annual survey of quitlines. North American Quitline Consortium 2013; 2013. [Available from: http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.naquitline.org/resource/resmgr/2012_annual_survey/oct23naqc_2012_final_report_.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: Current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years — United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(35):1135–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham AL, Carpenter KM, Cha S, Cole S, Jacobs MA, Raskob M, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of Internet interventions for smoking cessation among adults. Substance abuse and rehabilitation. 2016;7:55–69. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S101660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor GMJ, Dalili MN, Semwal M, Civljak M, Sheikh A, Car J. Internet-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9:Cd007078. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007078.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sackett DLRW, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB. Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stead LF, Hartmann-Boyce J, Perera R, Lancaster T. Telephone counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;8:CD002850. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002850.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayes SC, Levin ME, Plumb-Vilardaga J, Villatte JL, Pistorello J. Acceptance and commitment therapy and contextual behavioral science: examining the progress of a distinctive model of behavioral and cognitive therapy. Behav Ther. 2013;44(2):180–98. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernandez-Lopez M, Luciano MC, Bricker JB, Roales-Nieto JG, Montesinos F. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for smoking cessation: A preliminary study of its effectiveness in comparison with cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(4):723–30. doi: 10.1037/a0017632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bricker J, Wyszynski C, Comstock B, Heffner JL. Pilot randomized controlled trial of web-based acceptance and commitment therapy for smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(10):1756–64. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry SJ, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Etter JF. A list of the most popular smoking cessation web sites and a comparison of their quality. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2006 Dec 8;(Suppl 1):S27–34. doi: 10.1080/14622200601039923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraser D, Kobinsky K, Smith SS, Kramer J, Theobald WE, Baker TB. Five population-based interventions for smoking cessation: a MOST trial. Translational behavioral medicine. 2014;4(4):382–90. doi: 10.1007/s13142-014-0278-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferguson J, Bauld L, Chesterman J, Judge K. The English smoking treatment services: one-year outcomes. Addiction. 2005;100(Suppl 2):59–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herd N, Borland R. The natural history of quitting smoking: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Addiction. 2009;104(12):2075–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02731.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stein MB, Roy-Byrne PP, McQuaid JR, Laffaye C, Russo J, McCahill ME, et al. Development of a brief diagnostic screen for panic disorder in primary care. Psychosomatic medicine. 1999;61(3):359–64. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199905000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lang AJ, Stein MB. An abbreviated PTSD checklist for use as a screening instrument in primary care. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43(5):585–94. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) 2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86(9):1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gifford EV, Kohlenberg BS, Hayes SC, Pierson HM, Piasecki MP, Antonuccio DO, et al. Does acceptance and relationship focused behavior therapy contribute to bupropion outcomes? A randomized controlled trial of functional analytic psychotherapy and acceptance and commitment therapy for smoking cessation. Behav Ther. 2011;42(4):700–15. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farris SG, Zvolensky MJ, DiBello AM, Schmidt NB. Validation of the Avoidance and Inflexibility Scale (AIS) among treatment-seeking smokers. Psychological assessment. 2015;27(2):467–77. doi: 10.1037/pas0000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benowitz NL, Jacob P, III, Ahijevych K, Jarvis MJ, Hall S, LeHouezec J, et al. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2002;4(2):149–59. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hedeker D, Mermelstein RJ, Demirtas H. Analysis of binary outcomes with missing data: missing = smoking, last observation carried forward, and a little multiple imputation. Addiction. 2007;102(10):1564–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelson DB, Partin MR, Fu SS, Joseph AM, An LC. Why assigning ongoing tobacco use is not necessarily a conservative approach to handling missing tobacco cessation outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(1):77–83. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.West R, Hajek P, Stead L, Stapleton J. Outcome criteria in smoking cessation trials: proposal for a common standard. Addiction. 2005;100(3):299–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin B. On the Holm, Simes, and Hochberg multiple test procedures. American journal of public health. 1996;86(5):628–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.5.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes Factors. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1995;90:773–95. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wetzels R, Matzke D, Lee MD, Rouder JN, Iverson GJ, Wagenmakers EJ. Statistical Evidence in Experimental Psychology: An Empirical Comparison Using 855 t Tests. Perspectives on psychological science: a journal of the Association for Psychological Science. 2011;6(3):291–8. doi: 10.1177/1745691611406923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2016. [Available from: https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morery RD, Rouder N. Bayes Factor: Computation of Bayes Factors for Common Designs. 2015 0.9.12-2 ed. p. R package. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern Applied Statistics with S. 4th. New York: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kahan BC, Morris TP. Reporting and analysis of trials using stratified randomisation in leading medical journals: review and reanalysis. Bmj. 2012;345:e5840. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeffreys H. Theory of probability. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cobb NK, Graham AL, Bock BC, Papandonatos G, Abrams DB. Initial evaluation of a real-world Internet smoking cessation system. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(2):207–16. doi: 10.1080/14622200500055319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crutzen R, Cyr D, de Vries NK. The role of user control in adherence to and knowledge gained from a website: randomized comparison between a tunneled version and a freedom-of-choice version. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(2):e45. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McClure JB, Shortreed SM, Bogart A, Derry H, Riggs K, St John J, et al. The effect of program design on engagement with an internet-based smoking intervention: randomized factorial trial. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(3):e69. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayes SC. ACT Randomized Controlled Trials since 1986–2017. [Available from: https://contextualscience.org/ACT_Randomized_Controlled_Trials.

- 44.Gucht K, Griffith JW, Hellemans R, Bockstaele M, Pascal-Claes F, Raes F. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for adolescents: Outcomes of a large-sample, school-based, cluster-randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness. 2017;8(2):408–16. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dillman DA. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 2nd. Hoboken, NH: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hartmann-Boyce J, Lancaster T, Stead LF. Print-based self-help interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD001118. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001118.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hollis JF, McAfee TA, Fellows JL, Zbikowski SM, Stark M, Riedlinger K. The effectiveness and cost effectiveness of telephone counselling and the nicotine patch in a state tobacco quitline. Tob Control. 2007;16(Suppl 1):i53–9. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.019794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abrams DB, Orleans CT, Niaura RS, Goldstein MG, Prochaska JO, Velicer W. Integrating individual and public health perspectives for treatment of tobacco dependence under managed health care: A combined stepped-care and matching model. Ann Behav Med. 1996;18(4):290–304. doi: 10.1007/BF02895291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.