Abstract

Previous research involving dramatic performances about Alzheimer’s Disease and dementia perception have targeted health care workers or caretakers. We examined the influence of a theater performance on the emotional affect of a general audience to determine the utility of this type of theater in large-scale public health education efforts. Our study included 147 participants that attended a self-revelatory theater performance based on the social/relationship experiences of those with dementia and those who care for them. This type of theater engages the audience and actors in a dual transformative process, supporting the emotional growth of all involved. Participants completed pre- and post-performance questionnaires regarding their beliefs and feelings surrounding the topic of dementia and the importance of the Arts for educating on issues surrounding dementia care. We tested for change in emotional affect pre- and post-performance using sensitivity and center of gravity statistical analyses. We found a significant change in emotional affect from and initial strong negative affect to slightly more positive/relaxed view after viewing the performance. Findings support self-revelatory theater as a resource to destigmatize preconceived notions of dementia. Large-scale community health education efforts could benefit from using this style of theater to elicit a change in audience perception of disease realities.

Keywords: Alzheimer Disease, Dementia, Art Therapy, Awareness, Neurodegenerative Diseases, Social Stigma

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a growing threat to the aging community, with a projected growth of 11 to 16 million diagnoses expected by 2050 [1]. The general public harbors many misconceptions and anxieties about AD, stemming from a lack of reliable information [2]. For example, in one nationally representative survey, 39.1% of respondents believe there is medication available to prevent the disease [3]. Because so many individuals will be affected as both patients and caregivers, Zeng et al. have identified a need for large-scale community education efforts to relieve this confusion and psychological burden [4].

It is likely that any community education efforts will be received by an interested audience. While many adults experience anxiety surrounding AD, it appears that there is also a desire to be educated. A nationally representative survey suggested that most adults were interested in investigating their personal risk for developing AD [5]. Educational efforts could solidify understanding and retention in the general public, especially if those efforts are distributed across multiple formats and sources (i.e., text, audio, and video; online and offline) [6]. These findings support the demand for a resource to provide AD education that cannot be understood by the scientific presentation of statistics [7].

Performance art may be one such resource. “Self-revelatory performance” is a drama therapy model in which experimental problem solving and creative processes intersect to emotionally affect all involved, including both performers and audience members. The ultimate goal of self-revelatory performance is to communicate current, personal life issues from actor to audience in a mutually transformative process [8]. For a theater performance to be impactful, it must address certain areas of perception, including an altered perspective of the self during and after the performance as compared to before. The audience must have a meaningful learning experience while relating to the reality of the situation and to others [9]. This strategy allows for the interaction of the community and the self, resulting in accessible information processing on all levels. It has been shown that dramatic performance is an effective communication tool, especially when dealing with emotions and interpersonal relationships [10]. Self-revelatory performances seek to immerse the audience in a personal journey, encouraging cognitive processes in cooperation with emotional experiences to reshape their preconceived views. Theatre performances portraying dementia specifically, have shown a lasting impact on audiences in the form of positively transformed behavior and perception. For example, one recent study showed that individuals exposed to a performance about dementia experienced a long-term change to a more positive affect [11]. Employing self-revelatory performance methods promotes a positive learning experience for the cast and audience members [8], and can ultimately lead to a shift in opinions of stigmatized diseases [11].

To further investigate the utility of self-revelatory performance as a tool to change perception of dementia, we examined pre-performance and post-performance affect [arousal, positive, and negative emotion], to evaluate the utility of theater performance in public health education. The research team worked in conjunction with a theater company experienced in self-revelatory performance and creative aging to assess the responses of audience members to the performance. We hypothesized that a self-revelatory theater performance centered on the social and relationship aspects of AD and dementia would positively impact the perception the audience had of AD or other dementias.

Methods

Design

Approximately 1 month before performances were to begin Arts and AGEing Kansas City (AAKC), a non-profit arts organization, approached the University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Disease Center (KU ADC) about collecting data from the audience on four performances of an upcoming play, Seven Stages, Seven Stories. The non-profit was going to stage the plays with open seating during a summer festival. The play had already been written and was in rehearsal. After discussing possible options, and in consideration of the short timeline, the KU ADC offered assistance with an observational assessment of community members attending the production. The investigative team worked with the University of Kansas Medical Center Human Subjects Protection Program. Through these discussions it was determined that the investigative team could suggest appropriate questionnaire items and analyze data but could not be part of the data collection, and PHI could not be associated with any data collection.

The Play

The play was performed in approximately 1-hour and provided seven different perspectives of memory loss; husband, wife, mother, father, male and female partner and grandparent. The performance had a cast of thirteen volunteers ranging in age from 5 to 85, with varying levels of acting experience. A main goal of the performance was to craft a believable, impactful experience about Alzheimer’s disease or dementia for the audience. The cast members each had personal experience with Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia, as either a family member, friend, or caregiver.

The play had been written by members of AAKC, including individuals with Alzheimer’s, caregivers of a person with Alzheimer’s, and an individual who held two National Council of Certified Dementia Practitioners certificates: Certified Dementia Care Manager and Dementia Practitioner to ensure accuracy. Script development was based on live listening groups and 1:1 sessions, which took approximately 2 months. One writer stated, “Our theater productions are inspired by life stories that morph into live self-revelatory plays.” She emphasized that the performance was “all a tribute to the strength and patience it takes to live with Alzheimer’s, as a patient and a caregiver.” Each scene delivered a new perspective, allowing the audience to witness a range of emotional experiences. An example of a scene performed includes a woman named Mina telling the story about her partner, Rosie who has been diagnosed with dementia. “One Sunday, Rosie accidently sits down on the lap of another congregation member as they were trying to get seated in a pew. Rosie is completely unaware that she has done anything inappropriate, and Mina is tugging on her arm, asking her to get up. The surrounding people start to giggle, and it’s all right in the middle of service.” The goal of this scene was to communicate to the audience that humor is an important coping mechanism. Other values guiding the scenes included honesty, optimism, creativity and poignancy.

Procedure

Promotion was conducted by Arts and AGEing staff and the festival through a multiple channel approach, including mass emailing, word of mouth, and radio and newspaper advertising in association with festival promoters where the play was being performed.

Participants were asked to arrive 30 minutes before the performance to read the study explanation and complete the pre-performance questionnaire. An AAKC volunteer explained the purpose of the performance and gave participants time to read a letter summarizing the project and emphasizing their right to withhold their participation in any part of the project. Following the letter, the participants completed the pre-performance questionnaire. Immediately after finishing the performance, a post-performance questionnaire was administered. The pre-post data were intended to be paired on a single questionnaire distributed within the play handbill. However, due to a miscommunication between the theater company and the research team, the pairing was lost between the pre- and post-performance questionnaires.

Measures

Through mutual discussions with a theater company leader and the research team, questionnaires were developed. The pre-performance questionnaire contained a demographics (gender, age and race/ethnicity) and a yes/no relation to dementia section (knowing someone, having or being a caregiver for someone with dementia). Preliminary effectiveness was assessed both at pre and post-performance by asking three questions about comfort with conversations about AD, perception of importance of creative arts in dealing with AD and emotions towards AD. The first question asked about the audience member’s comfort with having a conversation with someone with AD or other dementia, with responses ranging from “Not comfortable at all” (1) to “Very comfortable” (5) to gauge participants’ perception of AD. The second question asked the audience member’s opinion on the importance of creative arts in dealing with AD or other dementias, with responses ranging from “Not important at all” (1) to “Very important” (5), in order to understand the perceived utility of theater in expressing dementia realities. The third question measured overall emotions towards dementia, respondents marked their current feelings on a 9×9 affect grid with labels at each corner [12]. This is a single item scale that assesses affect along the dimensions of unpleasant to pleasant feelings and high arousal to sleepiness. Clockwise from top left these were: Stress, Excitement, Relaxation, and Depression.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis of the data consisted of two parts, one related to the two Likert type responses and the other to the bivariate data. The Likert type responses were analyzed individually using a sensitivity analysis on an Ordinal Quasi Symmetry (OQS) model: Log (πab/πba) = β(μa-μb), which is a function of the scoring assigned to the responses, were assigned scores 1 through 5. Because we lost pre- to post-performance pairing, we assessed the implications of systematic variation in our items. Our null hypothesis was that the pre- and post-response probabilities did not change in a systematic way; under this hypothesis any variation was random. In our model this would be represented by β=0. Using this model to test the null hypothesis, we used R [13] to permute 10,000 possible unique pairings between the pre- and post-performance responses and then evaluated the β parameter for each possible pairing.

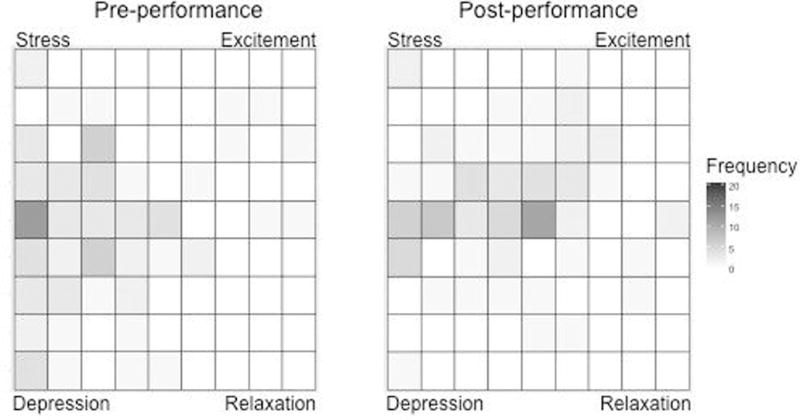

The bivariate data was analyzed by measuring center of gravity, the two-dimensional point around which a set of data are balanced, of both the observed pre- and post-performance responses and calculating the distance between them (Figure 1). Any grids with multiple answers were removed from the analysis. We then compared this distance to simulated distances. Under our null hypothesis the pre- and post-performance responses were random draws from the same distribution. We weighted the observed responses based on sample size to get an estimate of this underlying distribution and then randomly drew 10,000 pre- and post-performance pairings under this estimated distribution and calculated the simulated distances.

Figure 1.

Center of gravity of affect for observed pre- and post-bivariate data (pre-performance n=147, post-performance n=128). Participants were asked to put an ‘X’ in the grid box that best described “mix or shade of emotions that most closely represents your feelings” about Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias.

Results

Description of the Sample

Demographic data for respondents is available in Table 1. There were 147 at least partially complete pre-performance questionnaires and 128 at least partially completed post-performance questionnaires. The mean age of the sample was 57.2 years (SD 16), 71.6% were women and 91.0% were non-Hispanic white. Most respondents knew someone with dementia (85.5%), 2.7% had been diagnosed with dementia and 20.7% were current caregivers of someone with dementia.

Table 1.

Demographics of Audience Respondents (n=147)

| n | %/SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 101 | 71.6 |

| Male | 40 | 28.4 |

| Age (years) | 57.2 | 16 |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 3 | 2.2 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 121 | 91.0 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 5 | 3.8 |

| Non-Hispanic other and multiple race | 4 | 3.0 |

| Know someone with AD or other dementia | ||

| Yes | 124 | 85.5 |

| No | 21 | 14.5 |

| Diagnosed with AD or other dementia | ||

| Yes | 4 | 2.7 |

| No | 142 | 97.3 |

| Caregiver for someone with AD or other dementia | ||

| Yes | 30 | 20.7 |

| No | 115 | 79.3 |

Questionnaire Items

Conversation Comfort: The mean of the Conversation Comfort item was 4.34/5 at pre-performance and 4.66/5 at post-performance assessment. Baseline values of comfort with conversation did not differ statistically by age (rho=0.15; p=0.07) nor between those who knew someone with dementia (4.39) or did not (4.10; p=0.20) but were statistically different between those who were caregivers of someone with dementia (4.67) and those who were not (4.26; p=0.02). For the Conversation Comfort item we permuted 10,000 possible samples and got a median β = 0.444. This would imply that the probability of a shift from “Not comfortable at all” (1) to “Very comfortable” (5), is exp(.4436095*4) = 5.89 times as likely as a shift from 5 to 1, where the 4 represents the difference in the scores. None of the pairings resulted in a value less than 1.2. This is evidence that our analysis plan and data were fairly robust to possible pairings. All pairings resulted in a shift in the same direction, with more than 98% of these pairings resulting in a p-value < .05. We conclude that there is a positive shift in responses from pre- to post-performance based on the value and magnitude of the β parameter, which we interpret as a higher probability of having a more favorable response after the performance than before it.

Importance of Creative Arts: The mean of the Importance of Creative Arts” item was 4.53/5 at pre-performance and 4.77/5 at post-performance assessment. Baseline values of importance of creative arts did not differ statistically by age (rho=0.11; p=0.23), nor between those who knew someone with dementia (4.53) and those who did not (4.47; p=0.76) nor those who were (4.72) or were not (4.47; p=0.07) caregivers. For the 10,000 permuted pairings of the Importance of Creative Arts item we got a median β = 0.516. This would imply that the probability of a shift from “Not important at all” (1) to “Very important” (5), is 7.88 times as likely as a shift from 5 to 1. None of the pairings resulted in a value below 1.4, indicating a positive shift in response. The p-values for all 10,000 pairings were p < 0.05.

We concluded that our results were robust to changes in possible pairings and we are confident that there was a positive shift in perception of the values of creative arts between the pre- and post-performance questionnaires for both of the Likert items.

Bivariate Question

To quantify the distance between the two centers of gravity for our affect measure, we simulated 10,000 differences between simulated pre- and post-performance data. Out of these 10,000 simulations only 7 were as or more extreme than our observed value. In relation to the simulated differences the observed distance is very extreme, resulting in a simulated p < 0.001 (Figure 1). We concluded that there was a shift away from the overtly negative perspective of dementia.

Discussion

Theater performances based on research have been considered a pedagogical tool, in that they communicate disease experiences while also positively influencing the affect or knowledge of the viewers [14]. Our findings were consistent with previous research. We found that overall; viewers were emotionally influenced by a single performance. They also expressed improved comfort with the idea of discussing dementia. The transformative nature of art performances is supported through the significant shift of audience perception after viewing “Seven Stages Seven Stories”.

Previous research [11, 14, 15, 16] has focused mainly on educating health care workers, caretakers, and diagnosed patients. Those prior studies directly engaged with individuals involved in the dementia care process, and demonstrated an increase in understanding and caretaking approaches among their target audience. Our study applies this same idea to a convenience sample of community members in which the majority knew someone with dementia but were not caregivers. Our findings suggest that a self-revelatory theater performance can positively influence people that are not necessarily directly exposed to dementia/AD. Educating the public by addressing misconceptions and anxieties that surround the disease through art has the potential to solidify understanding and retention in a way that cannot be understood by the scientific presentation of statistics [7].

The project described here serves as a model for the opportunities and challenges when community members approach researchers to assist with collecting data. Perhaps, most importantly, collaborations such as this can provide insight into “real world” activities that are community created and driven. This performance would have occurred whether or not the KU ADC was able to assist with capturing data. The project has also proved to be an entry point for ongoing service and research collaboration between the KU ADC and AAKC. However, the late invitation for involvement led to missed chances to collect additional data and an inability to educate the AAKC on optimal data collection methods. With additional time and discussion, it is likely that pre- and post-performance questionnaires would have remained paired.

Neither the play nor the project was designed to assess feasibility or cost-effectiveness. The production was performed to free, open seating at a summer festival and the AAKC preferred to focus on possible affect changes. Additionally, though we view the heterogeneous nature of the production as a strength for potential generalizability to the public, translation to a more specific audience such as caregivers or family, or scaling to more audiences may not be feasible. Future work may wish to consider feasibility, scalability, and cost-effectiveness by comparing this intervention to standard community presentations. There is some precedent for dramatic arts education that is scalable, the African-American oriented stage play “Forget Me Not” written by Garrett Davis, that has traveled around the country over the last 5 years.

There are several limitations in our study. As noted the pairing between pre- and post-performance questionnaires was lost. Therefore, we were unable to pair affect change for an individual pre- and post-performance. We instead used simulation methods as a sensitivity analysis for our measured outcomes. We also found that some respondents had difficulties in understanding the affect grid, which may have led to a slight misrepresentation of emotional response. We also acknowledge a self-selection bias in that the audience (our respondents) chose to attend the performance. The project would have enjoyed greater rigor had the theater and investigative teams collaborated from the inception of the play. There are sections of the play that might be difficult to understand by some people with dementia. However, this performance was targeted at the general public. A final limitation comes from the lack of ability in determining the performances long-term effects on perception. While this study did not record a longitudinal follow up ensuring long term affect change, Dupuis et al suggests a significant lasting effect following theater performance is possible [11]. Nevertheless, we believe our experience can serve as an example for future community/research collaborations. Future work may benefit from a wider audience such as schools or faith group without a potential self-selection bias for attendance. We encourage researchers to explore the dual transformative nature of self-revelatory theater by surveying actors pre- and post-performance to determine a shift in emotional affect.

It is of utmost importance that the public perception of dementia/AD is improved [4]. Theater performances represent an effective support system to broadly disperse knowledge about these diseases, which could ultimately reverse the societal stigma. This pedagogical tool could also increase compassion and awareness towards those suffering, directly affected by, and indirectly affected by this growing threat to the aging community. In evaluating data collected before and after respondents viewed a performance on dementia, the perception of dementia transformed from a strong negative affect to slightly more positive/relaxed affect. This finding supports self-revelatory performance art as a reliable method in influencing and increasing public awareness of dementia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health [grant number P30 AG035982]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s A. 2015 alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(3):332–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts JS, McLaughlin SJ, Connell CM. Public beliefs and knowledge about risk and protective factors for alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(5 Suppl):S381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connell CM, Scott Roberts J, McLaughlin SJ. Public opinion about alzheimer disease among blacks, hispanics, and whites: Results from a national survey. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(3):232–240. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181461740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeng F, Xie WT, Wang YJ, Luo HB, Shi XQ, Zou HQ, Lian Y. General public perceptions and attitudes toward alzheimer’s disease from five cities in china. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43(2):511–518. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson LA, Day KL, Beard RL, Reed PS, Wu B. The public’s perceptions about cognitive health and alzheimer’s disease among the u.S. Population: A national review. Gerontologist. 2009;49(Suppl 1):S3–11. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frisch AL, Camerini L, Schulz PJ. The impact of presentation style on the retention of online health information: A randomized-controlled experiment. Health Commun. 2013;28(3):286–293. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.683387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeilig H. Dementia as a cultural metaphor. Gerontologist. 2014;54(2):258–267. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emunah R. Self-revelatory performance: A form of drama therapy and theatre. Drama Therapy Review. 2015;1(2):71–85. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell GJ, Dupuis S, Jonas-Simpson C, Whyte C, Carson J, Gillis J. The experience of engaging with research-based drama: Evaluation and explication of synergy and transformation. Qualitative Inquiry. 2011;17(4):379–392. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colantonio A, Kontos PC, Gilbert JE, Rossiter K, Gray J, Keightley ML. After the crash: Research-based theater for knowledge transfer. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28(3):180–185. doi: 10.1002/chp.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dupuis SL, Mitchell GJ, Jonas-Simpson CM, Whyte CP, Gillies JL, Carson JD. Igniting transformative change in dementia care through research-based drama. Gerontologist. 2015 doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russell J, Weiss A, Mendelsohn G. Affect grid: A single-item scale of pleasure and arousal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57(3):493–502. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Team, R.C. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013. Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kontos PC, Naglie G. Expressions of personhood in alzheimer’s disease: An evaluation of research-based theatre as a pedagogical tool. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(6):799–811. doi: 10.1177/1049732307302838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gjengedal E, Lykkeslet E, Sorbo JI, Saether WH. ‘Brightness in dark places’: Theatre as an arena for communicating life with dementia. Dementia (London) 2014;13(5):598–612. doi: 10.1177/1471301213480157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonas-Simpson C, Mitchell GJ, Carson J, Whyte C, Dupuis S, Gillies J. Phenomenological shifts for healthcare professionals after experiencing a research-based drama on living with dementia. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(9):1944–1955. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]