Abstract

Purpose

US Latino/a parents of adolescents face unprecedented threats to family stability and well-being due to rapid and far-reaching transformations in US immigration policy.

Methods

213 Latino/a parents of adolescents were recruited from community settings in a suburb of a large mid-Atlantic city to complete surveys assessing parents’ responses to immigration actions and news as well as parents’ psychological distress. Univariate and bivariate analyses were conducted to describe the prevalence of parents’ responses to immigration news and actions across diverse residency statuses. Multiple logistic regression models examined associations between immigration-related impacts and the odds of a parent’s high psychological distress.

Results

Permanent residents, TPS, and undocumented parents reported significantly more negative immigration impacts on psychological states than US citizens. Parents reporting frequent negative immigration-related impacts had a significantly higher likelihood of high psychological distress than did other parents, and these associations were maintained even when accounting for parents’ residency status, gender, education, and experience with deportation or detention. The odds of a parent reporting high psychological distress due to negative immigration impacts ranged from 2.2 (P<.05) to 10.4 (P<.001).

Conclusions

This is one of the first empirical accounts of how recent immigration policy changes and news have impacted the lives of Latino families raising adolescent children. Harmful impacts were manifest across a range of parent concerns and behaviors and are strong correlates of psychological distress. Findings suggest a need to consider pathways to citizenship for Latino/a parents so that these parents, many of whom are legal residents, may effectively care for their children.

Keywords: Immigration, Latino Families, Parent Psychological Distress, Adolescents

Media reports indicate that US Latina/o immigrants have experienced heightened stress and threats to family stability since the new President took office in 2017 [1,2]. However, little empirical data document how rapid changes in immigration news and actions are affecting Latina/o (hereafter, referred to as Latino) families. Adverse consequences of today’s immigration climate may be pronounced for Latino parents with adolescent children. Compared to younger children, adolescents have a better cognitive understanding of the stressors their families face, experience more direct exposure to extrafamilial risks, and have spent more formative years of identity development within a US context [3]. The present study describes parents’ behavioral and emotional responses to recent immigration actions and news and investigates how these responses are associated with Latino parents’ psychological distress. We describe how immigration-related impacts vary by residency status, conceptualized along a hierarchy from the most to least secure categories [4]. Participants included those who were US-born and naturalized US citizens (most secure), permanent residents, Temporary Protected Status1 residents, and undocumented residents (least secure).

Extensive research has described stressors experienced by US Latinos [6,7], particularly the undocumented [8–15]. Latino immigrants often experience fear of deportation, exploitation by employers [9], trauma [16], distrust in public services [17], language barriers, racism [12], and financial strain [18]. These stressors are important predictors of psychological distress, indicated by anxiety, depression, and somatization [13,19,20]. The costs and burdens of psychological distress extend far beyond an affected individual. Parents’ psychological distress is especially important; adolescents whose parents are depressed and/or anxious face heightened risk of poor social functioning [21], academic failure [22], and mental health problems [21].

Immigration threats have impacts well beyond the acute harm conferred to the subset of Latinos directly experiencing events such as deportation [14,23]. Informed by public health’s injury pyramid, Dreby suggested that an event such as deportation severely hurts those at the top of the pyramid – Latinos experiencing deportation – but also produces less severe harm for a large number of Latinos at the bottom of the pyramid – those not directly experiencing deportation [24]. This is because politics, threats of deportation, and anti-immigrant sentiments lead to widespread fear and anxiety among Latinos not directly affected by the event [11,24,25].

Immigration actions and news likely are affecting Latino parents across diverse residency statuses. The most notable immigration policy changes in 2017 were: (1) expanded eligibility for deportation, which increased deportation of long-term residents without criminal records [26]; (2) the elimination of, and/or plans to eliminate, TPS [5, 27, 28]; and (3) an end to the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which has protected hundreds of thousands of undocumented Latinos brought to the US as children [29]. Our study provides some of the first evidence to date indicating how US Latino parents of adolescents cope, react, and manage emotions in response to recent immigration news and actions. Given that the adolescents of parents in this study were US citizens or brought to the US as children, our research can advance knowledge about the family context for a large and critical segment of the US population.

Methods

Procedures and sample

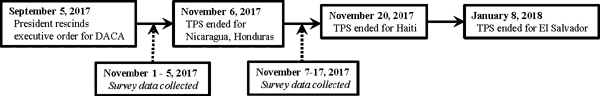

Drawing from a mixed-method study conducted in the Fall of 2017, we analyzed survey data for 213 Latina/o immigrant parents living in a suburban area of a large mid-Atlantic city in the US. Numerous immigration policy changes took place before, during, and immediately after our collection.2 The community includes a large Latino population, mostly from El Salvador and Guatemala and, to a lesser extent, from Mexico, Honduras, Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic. An author of this study with expertise in data collection among this community utilized her existing network to recruit participants. Survey-only respondents were provided $10 and those who also participated in the focus group were provided $50. Eligibility was limited to Latino parents with at least one child aged 12 to 18 years. The sample was stratified so that about one-third were undocumented (n = 69), one-third were permanent residents (n = 70), and the remaining one-third included the same number of US Citizen (n = 37) and TPS parents (n = 37).

Data collection was conducted in Spanish by bicultural and bilingual interviewers. In order to protect participants’ safety, we collected data anonymously, obtained oral consent only, and obtained a Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the institution where the research was conducted.

Measures

Residency Status

Parents’ residency status was measured by four dummy coded variables for US citizen (the reference group); permanent resident; TPS; and undocumented.

Immigration Impacts on Parents

The 15-item Political Climate Scale was used to assess impacts of immigration news and actions [30]. The instrument opens with: “As you know, there have been stories in the news about immigrants and immigration, and there have been official actions affecting immigrants and other people. We would like to know whether these news stories and official actions have affected you or your family over the past few months.” Parents responded to 15 statements indicating worry or behavior modification. The original 1 to 5 response options were recoded into “never/almost never, not very often, or sometimes” (the reference group) versus “very often or always/almost always.”

Parent’s Psychological Distress

A modified 16-item version of the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18) [31] was used to assess parent symptoms of depression, anxiety, and somatization (due to IRB concerns, two items - suicidal thoughts and chest pains - were removed). Parents reported being distressed or bothered in the past seven days by things such as feeling worthless, lonely, and nervousness (0 = “not at all” to 4 = “extremely”). Results from Principal Components Analysis indicated a single factor of psychological distress (α = .96). We recoded the summed average scores into a dichotomous variable, whereby, “high distress” represented the top quartile of scores (>= 3.19).

Background variables

Parent characteristics included sex (female was the referent); having at least a high school education (less than high school was the referent); living in the US more than 15 years (<= 15 was the referent); and being from El Salvador (referent group), Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, United States, or “Other.” We assessed if parents moved to the US for any of the following reasons: (a) get a better job or make more money; (b) improve education for their child; (c) escape gangs or violence; and/or (d) reunite with family in the US. Finally, we assessed whether or not the parent had a family member who was deported or detained since the new US President took office in January 2017.

Analyses

We ran cross-tabulations with chi-square tests to examine residency status differences in background variables and impacts of immigration actions and news. We then ran logistic regression models whereby parents’ psychological distress was regressed on variables measuring impacts of immigration actions and news. We excluded background measures that bivariate results suggested might pose a multi-collinearity problem. We report regression coefficients as unadjusted Odds Ratios (OR) and adjusted Odds Ratios (AOR), with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In post hoc analyses, we used two-way interaction terms to examine the degree to which immigration-related impacts on psychological distress differed for Latino parents in marginalized residency status groups (i.e. undocumented, TPS) versus others (i.e. US citizens, permanent residents). All analyses used two-tailed statistical tests.

Results

Participants included slightly more mothers than fathers. About half of the parents were El Salvadoran, with the remainder including mostly Central Americans and a small number of Mexicans and US-born parents. As shown in Table 1, virtually all TPS and US Citizen parents had lived in the US for more than 15 years, compared to less than two-thirds of permanent resident and less than one-third of undocumented parents. Over three-quarters of US Citizens had at least a high school degree, compared to 40% to 50% of permanent resident and undocumented parents, and less than one-fifth of TPS parents. While 60% of TPS parents reported that a family member had been detained or deported since the new president took office in 2017, less than a quarter of undocumented, permanent resident, and US Citizen parents reported a family member’s recent deportation or detention. Finally, the majority of youth whose parents are in this study are US citizens; just 30% of the non-US citizen parents report having a “DACA-eligible” child – one brought to the US prior to age 18 and lacking legal residency status.

Table 1.

Distribution of Sample Characteristics by Parents’ Residency Status, n = 213

| Undocumented n (%) | TPS n (%) | Resident n (%) | US Citizen n (%) | Total n (%) | Chi-Square (df) test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| County of origin | ||||||

| El Salvador | -- | -- | -- | -- | 117 (55.2) | -- |

| Guatemala | -- | -- | -- | -- | 25 (11.8) | -- |

| Honduras | -- | -- | -- | -- | 20 (9.4) | -- |

| Mexico | -- | -- | -- | -- | 17 (8.0) | -- |

| United States | -- | -- | -- | -- | 13 (6.1) | -- |

| Other | -- | -- | -- | -- | 20 (9.3) | -- |

| Live in US > 15 Yearsd | 21 (30.9)a | 35 (97.2)b | 45 (64.3)c | 36 (97.3)b | 137 (64.9) | χ2 (3) = 68.14*** |

| >= High School Educatione | 34 (49.3)a | 7 (18.9)c | 27 (38.6)a | 29 (78.4)b | 97 (45.5) | χ2 (3) = 28.42*** |

| Have DACA-eligible childf | 27 (39.1) | 9 (24.3) | 17 (24.3) | -- | 53 (30.1) | χ2 (2) = 4.39 |

| Fam mem deported/detainedg | 16 (23.5)a | 22 (59.5)b | 17 (24.6)a | 7 (18.9)a | 62 (29.4) | χ2 (3) = 19.95*** |

| Reason(s) moved to USh | ||||||

| Get a job or a better job | 12 (17.4)a | 15 (41.7)b | 12 (17.9)a | -- | 39 (22.7) | χ2 (2) = 9.37** |

| Better education for child | 26 (37.7) | 18 (48.6) | 23 (34.3) | -- | 67 (38.7) | χ2 (2) = 2.11 |

| Escape gangs or violence | 37 (53.6) | 24 (64.9) | 33 (49.3) | -- | 94 (54.3) | χ2 (2) = 2.37 |

| Reunite family in U.S. | 16 (23.2)a | 10 (27.0)a,b | 29 (43.3)b | -- | 55 (31.8) | χ2 (2) = 6.82* |

| High psychological distress | 16 (23.2)b | 18 (48.6)a | 19 (27.1)b | 3 (8.1)c | 56 (26.3) | χ2 (3) = 16.23*** |

Notes:

“--” indicates cell size was too small for cross-tabulation. Some categories do not add up to 213 due to item-level missing data. Proportions in the same row that do not share superscripts differ at p < .05 using Chi-square tests of significance.

Includes n = 13 parents born in the United States. Reference group: Lived in US < 15 years.

Reference group: Parent had less than a high school education.

Parent reports having an undocumented child brought to US prior to age 18. Among parents with “DACA-eligible” child, n = 14 (26.4%) report that their child has protection under the DACA program.

“Fam” = Family; “Mem” = member. Reference group: Had not had family member who was deported or detained since new US president took office January 2017.

Analyses excluded US Citizens due to small numbers of those born outside US; respondents may mark more than one reason.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Just over 40% of TPS parents moved to the US in order for the parent or spouse to improve their employment situation, compared to less than a fifth of permanent resident and undocumented parents. In addition, over 40% of permanent residents moved to reunite with family in the US, compared to about a quarter of TPS and undocumented parents. Over half of the non-US citizen parents (i.e., TPS, undocumented, permanent residents) moved to the US to escape gangs or violence and almost 40% did so for their children to get a better education. Finally, almost half of TPS parents (48.6%) reported high psychological distress, compared to about a quarter of undocumented (23.2%) and permanent resident (27.1%) parents and just 8.1% of US citizen parents.

Variations in immigration impacts by parents’ residency status

Table 2 presents results for parental responses to immigration actions and news. As shown, the majority of TPS and undocumented parents reported that immigration news and actions led them to very often or always (1) worry about family separation; (2) feel their child had been negatively affected; and (3) worry it would be hard for their child to finish school. Although TPS parents were more likely than other groups to report concerns about the safety and well-being of the family and children, substantial proportions of undocumented and permanent resident parents reported these same concerns. Specifically, a high proportion of TPS, undocumented, and permanent resident parents reported having frequently (1) warned their children to stay away from authorities; (2) talked to their children about changing behaviors such as where they hang out; (3) avoided seeking medical care, public assistance (e.g., SNAP, WIC), or help from the police; and (4) felt that their child or themselves had been negatively affected by immigration actions and news. Undocumented parents were most likely to report jobs concerns including (1) having had a hard time imagining they could get a job or keep a job, (2) believing it would be hard to get a better job or make more money, and (3) worrying that it would be hard for their children to get a job. There were no significant differences in the proportions of TPS, undocumented, and permanent residents who reported frequently changing daily routines or worrying about contact with authorities such as police.

Table 2.

Proportion of Parents in Different Residency Status Reporting “Very Often” or “Almost Always/Always” Experiencing Outcomes due to Immigration News and Events, n = 213

| Due to Immigration Actions and News, Parent Very Often or Almost Always/Always… | Undocumented n (%) | TPS n (%) | Resident n (%) | US Citizen n (%) | Total n (%) | Chi-Square (df) significance test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hard to get or keep a job | 33 (47.8)a | 11 (29.7)a,b | 17 (24.3)b | 2 (5.4)c | 63 (29.6) | χ2 (3) = 22.35*** |

| Hard to imagine better job, more money | 48 (69.6)a | 15 (40.5)b | 25 (35.7)b | 6 (16.2)c | 94 (44.1) | χ2 (3) = 32.00*** |

| Worried will be hard for child to get job | 42 (60.9)a | 21 (56.8)a,b | 29 (42.0)b | 6 (16.2)c | 98 (46.2) | χ2 (3) = 21.50*** |

| Warned child to stay away from authorities | 38 (55.1)a | 28 (77.8)b | 30 (42.9)a | 5 (13.5)c | 101 (47.6) | χ2 (3) = 32.55*** |

| Worried family members will get separated | 61 (88.4)a | 31 (83.8)a | 40 (57.1)b | 8 (21.6)c | 140 (65.7) | χ2 (3) = 55.35*** |

| Changed daily routines | 28 (41.2)a | 17 (45.9)a | 22 (31.4)a | 3 (8.1)b | 70 (33.0) | χ2 (3) = 15.30** |

| Avoided medical care, police, services | 29 (42.0)a | 23 (62.2)b | 24 (34.3)a,c | 8 (21.6)c | 84 (39.4) | χ2 (3) = 13.89** |

| Child negatively affected | 39 (56.5)a | 22 (61.1)a | 25 (37.3)b | 6 (16.2)c | 92 (44.0) | χ2 (3) = 21.47*** |

| Worried hard for child finish school | 40 (58.0)a | 28 (75.7)a | 24 (34.3)b | 6 (16.2)c | 98 (46.0) | χ2 (3) = 34.18*** |

| Child affected at school | 26 (37.7)a | 24 (64.9)b | 23 (32.9)a | 5 (13.9)c | 78 (36.8) | χ2 (3) = 21.15*** |

| Parent negatively affected | 34 (50.0)a,b | 24 (64.9)a | 30 (44.1)b | 7 (18.9)c | 95 (45.2) | χ2 (3) = 16.76** |

| Worried contact with police, authorities | 24 (34.8)a | 12 (32.4)a | 21 (30.4)a | 4 (10.8)b | 61 (28.8) | χ2 (3) = 7.38 |

| Talked to child about changing behavior, such as where s/he hangs out | 37 (53.6)a,b | 24 (64.9)a | 31 (44.3)b | 8 (21.6)c | 100 (46.9) | χ2 (3) = 15.73** |

|

| ||||||

| Total | n = 69 | n = 37 | n = 70 | n = 37 | n = 213 | |

Notes: Bolded numbers signify the residency status with the highest proportion of parents reporting “often” or “almost always/always” experiencing a particular adverse outcome. Proportions in the same row that do not share superscripts differ at p < .05 using Chi-square tests of significance.

Due to small cell sizes, we do not present results for the most extreme immigration consequences; these responses did not differ significantly by residency status. Overall, between 14% and 18% of parents reported “very often” or “almost always/always” being stopped, questioned or harassed, and/or considered leaving the country. US citizens were least likely to report all other adverse immigration impacts.

How immigration impacts matter for parents’ psychological distress

A parent’s odds of being highly psychologically distressed were significantly greater if the parent frequently modified behavior in response to immigration actions and news. Results in Table 3 include unadjusted odds ratios as well as adjusted odds ratios. The odds of a parent’s high psychological distress were 118% greater for parents who frequently avoided contact with authorities such as the police (44.3% vs. 19.2%, AOR = 2.18, CI: 1.03 – 4.60) and three to four times greater for parents who frequently warned their child to stay away from authorities (43.6% vs. 9.9%, AOR = 4.06, CI: 1.75 – 9.45); worried it would be hard for their child to get a job (40.8% vs. 14.0%, AOR = 3.19, CI: 1.49 – 6.81); worried that family members would get separated (35% vs. 9.6%, AOR = 3.52, CI: 1.28 – 9.67); and considered leaving the U.S. (51.4% vs. 20.6%, AOR = 4.13, CI: 1.71 – 9.96). The odds of high psychological distress were 8–11 times higher when parents reported that, due to immigration actions and news, they had frequently been stopped, questioned or harassed (60.0% vs. 21.0%, AOR = 8.03, CI: 2.68 – 24.05); avoided seeking medical care or assistance from police and government services (48.8% vs. 11.6%, AOR = 5.30, CI: 2.45 – 11.47); talked to their child about changing behaviors such as where the child hangs out (49.0% vs. 6.2%, AOR = 8.74, CI: 3.42 – 22.39); felt negatively affected (49.5% vs. 7.8%, AOR = 7.78, CI: 3.33 – 18.20); believed that their children had been negatively affected (51.1% vs. 6.8%, AOR = 10.39, CI: 4.01 – 26.92); expected their children would have a hard time finishing school (48.0% vs. 7.8%, AOR = 9.85, CI: 3.81 – 25.42), and thought their children had been affected at school (55.1% vs. 9.0%, AOR = 7.65, CI: 3.33 – 17.53). Once control variables were included, parent reports of having changed daily routines, feeling it was harder to find or keep a job, and having a hard time imagining getting a better job or making more money, were not associated with parents’ psychological distress.3

Table 3.

Immigration Actions and News as Correlates of Parent’s High Psychological Distress (n = 213)a, b

| Number | % | Bivariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Due to Immigration Actions and News, Parent “Very Often” or “Always”…c | # | % | OR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI |

| Believe hard to find or keep a job | 63 | 29.6 | 2.67** | (1.38–5.20) | 1.79 | (.82–3.88) |

| Believe hard to get better job, more money | 94 | 44.1 | 1.76 | (.93–3.32) | 1.56 | (.73–3.33) |

| Worried will be hard for child to get job | 98 | 46.2 | 3.86*** | (1.96–7.57) | 3.19** | (1.49–6.81) |

| Warned child to stay away from authorities | 101 | 47.6 | 6.48*** | (3.08–13.64) | 4.06** | (1.75–9.45) |

| Worried family members will get separated | 140 | 65.7 | 5.82*** | (2.34–14.43) | 3.52* | (1.28–9.67) |

| Changed daily routines | 70 | 33.0 | 3.24*** | (1.68–6.25) | 2.07 | (.99–4.32) |

| Avoided medical care, police, services | 84 | 39.4 | 7.67*** | (3.77–15.61) | 5.30*** | (2.45–11.47) |

| Child has been negatively affected | 92 | 44.0 | 15.79*** | (6.60–37.77) | 10.39*** | (4.01–26.92) |

| Worried will be hard for child finish school | 98 | 46.0 | 12.03*** | (5.26–27.51) | 9.85*** | (3.81–25.42) |

| Child has been affected at school | 78 | 36.8 | 13.22*** | (6.12–28.57) | 7.65*** | (3.33–17.53) |

| Has been negatively affected | 95 | 45.2 | 11.25*** | (5.06–25.01) | 7.78*** | (3.33–18.20) |

| Avoided contact with police, authorities | 61 | 28.8 | 3.21** | (1.64–6.28) | 2.18* | (1.03–4.60) |

| Considered leaving U.S. | 37 | 17.5 | 4.00*** | (1.85–8.64) | 4.13** | (1.71–9.96) |

| Been stopped, questioned, harassed | 30 | 14.2 | 5.72*** | (2.38–13.76) | 8.03*** | (2.68–24.05) |

| Talked to child about changing behavior, such as where child hangs out | 100 | 46.9 | 14.50*** | (6.09–34.51) | 8.74*** | (3.42–22.39) |

Note: OR – odds ratio; AOR – adjusted odds ratio CI – confidence interval.

P≤.05;

P≤.01;

P≤.001;

Each immigration impact variable was examined in separate logistic models.

Adjusted models control for parent’s residency status; gender; having at least a high school education; and, reporting that a family member was detained or deported since the new President took office in 2017. Years living in the US and country of origin were not included in multivariate models due to multicollinearity with residency status.

The reference group includes responses of “never/almost never,” “not very often,” or “sometimes.”

Discussion

Contemporary immigration actions and news have had profound and far-reaching adverse impacts on US Latino parents raising adolescents. In a departure from prior research [9,20], this descriptive study is informative about Latino parents across a hierarchy of residency statuses. Although parental worries and behavior modifications tied to immigration actions and news were least prevalent among US citizens, pernicious immigration-related consequences were by no means limited to the undocumented. Across non-citizen groups, especially those with TPS, parents experienced concern for family, as indicated by parents’ warning their children to avoid authorities; avoiding medical care, public assistance, or the police; and, worrying that their children had been negatively affected at school due to immigration actions and news. Similarly high proportions of TPS and undocumented parents had frequently talked to their children about changing behaviors such as where they hang out; felt that the immigration actions and news negatively affected the parent; and worried about their own and their children’s job prospects. As suggested by research on DACA recipients [16], the vulnerability of TPS parents in this study may stem from the temporary nature of the TPS program and/or the stress of having undocumented family members [5,33]. Almost all TPS parents in this study has lived in the US for more than 15 years, and 60% had experienced a family member’s deportation or detention during the first nine months of the new president’s term in office. Taken together, these findings highlight the pronounced vulnerability of TPS parents vis-à-vis today’s immigration changes.

Evidence for adverse consequences of immigration actions and news across residency statuses is consistent with research indicating that immigration policy can be equally harmful to documented and undocumented Latinos [24,33]. TPS and, in some cases, permanent resident parents were at least as harmed by immigration events as were undocumented parents. In this way, our findings do not support the idea of “hierarchy” of residency status but rather point to the uniquely protective value of having US citizenship. A substantial proportion of non-US citizen parents frequently engaged in behaviors designed to avoid the attention of government authorities. These parental responses align with prior research indicating that Latino immigrants often hesitate contacting police for fear of mistreatment and/or the deportation of another family member [34]. Given that over half of the non-US citizen parents in this study moved to the US in order to escape gangs and violence, unease among these parents is especially understandable. Regardless of residency status, a small proportion of Latino parents (approximately 15% to 18%) reported “very often” or “always” considering leaving the US and/or getting stopped, harassed, or questioned. These findings support the conclusion drawn by Enriquez that “sanctions intended for undocumented immigrants seeped into the lives of individuals who should have been protected by their citizenship status.”

Adverse immigration impacts were associated with at least a 300% increase in the odds of a parent having high psychological distress. Worrying about youth’s education, perceiving negative impacts on the family, being stopped/questioned/harassed, and considering leaving the US appeared to be especially harmful; frequently experiencing these outcomes was associated with more than an eight-fold increase in the odds of a parent’s high psychological distress. Unlike parental concerns about their family, parent aspirations for their own upward mobility (e.g., hoping to get a better job or make more money) appeared not to compromise parents’ mental health once accounting for background variables.

Regardless of societal concerns about the mental health and well-being of Latino adults, our findings raise serious concerns about the health and well-being of US Latino adolescents. Often, adolescents whose parents get deported experience post-traumatic stress disorder [10]. In this research, almost two-thirds of parents frequently worried about family separation and close to half frequently warned their adolescent children to stay away from authorities, talked to their children about changing behaviors such as where they hang out, and avoided access to medical care, police, and public assistance. These behaviors directly threaten youth’s safety and mental and physical health and can be indirectly harmful by way of parents’ psychological distress [35]. Although risks likely are magnified for adolescents whose parents are not US citizens, it is important to note that the vast majority of Latino adolescents in this study were US citizens. Thus, even though Latino youth themselves are not undocumented, they face risks to well-being on account of their parents’ vulnerable residency status [36].

This study is not without limitations and suggests important directions for future research. First, this study’s use of cross-sectional data limits causal inferences. Second, the reliance on self-reported data for a convenience sample of Latinos from a single immigrant community is limiting. A larger sample size would help elucidate findings for TPS parents, a group at heightened risk for adverse outcomes. Given that many Latino parents, may live in “mixed-status” families with documented and undocumented family members, it will be important for future research to explicitly investigate the unique difficulties faced by mixed-status families [37]. Third, given the small number of parents with children covered by the DACA program in this study, further research is needed to elucidate the degree to which DACA protections may or may not shield parents from immigration-related concerns and worries. Fourth, it is unclear how parental responses to today’s immigration actions and news might differ from those experienced during the Obama administration, which witnessed even higher numbers of deportations to Mexico and Central America. In this regard, however, any comparison is complicated by the fact that President Trump’s election in 2016 was followed by fewer attempted illegal crossings into the US, an increased number of deportations in the interior of the country, and expanded eligibility for deportation, resulting in more deportations of individuals with long histories of law-abiding behavior [38]. Finally, our study did not investigate Latino parents’ experiences of racism and discrimination. Yet, stress tied to discrimination experiences are highly prevalent among Latino immigrants and positively associated with anti-immigrant policies [39] and inequity due to residency status [12]. Given that parents’ reports of being frequently stopped, questioned, or harassed due to immigration actions and news did not differ by residency status, it is possible that immigration changes increased racial profiling for a much larger segment of the US Latino population than has been targeted by official immigrant actions.

Public discourse around immigration has progressed at a rapid pace since the 2016 presidential campaign and election. Extant research has demonstrated that residency status serves as a mechanism of social stratification affecting Latino citizen youth by blocking access to critical developmental resources [40]. The current study suggests that increased anti-immigrant and anti-Latino rhetoric taking place [1,2] may lead to psychological distress among Latino parents of adolescents – a finding that generalized to all four residency status groups. Community-based organizations must educate Latino residents about their rights, ensure that these rights are not violated, and counteract rumors that can have a chilling effect on Latino families’ use of public services. Given robust negative implications of parent psychological distress for adolescents [21,22], alongside the large portion of Latino adolescents who are U.S. citizens, pathways to citizenship for Latino parents are critical in order to mitigate long-term, collateral consequences for numerous Americans.

Implications and Contributions.

In response to rapid and unprecedented changes in immigration actions and news, high proportions of US Latino parents of adolescents reported recently having modified behaviors and experiencing worry. Adverse responses to immigration events were associated with more than a 300% greater odds of a US Latino parent’s high psychological distress.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by The George Washington University (PI: Roche; Cross-Disciplinary Research Award); the National Institutes of Health Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (PI: Guay-Woodford; grant numbers: UL1TR001876; KL2TR001877), and the William T. Grant Foundation (PI: White; grant number 182878).

The authors thank Roushanac Partovi, MPH and Tom Salyers for valuable contributions to this project and to the Latina/o parents who participated in this research.

List of abbreviations

- US

United States

- TPS

Temporary Protected Status

- SNAP

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

- WIC

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

- DACA

Deferred Action on Childhood Arrivals

Footnotes

TPS residents refer to those granted permission to live in the US due to extraordinary and temporary conditions in the country of origin [5].

Timeline of survey data collection and policy announcements:

Post hoc analyses indicated that just three of 15 two-way interaction terms between residency status and immigration impacts were statistically significant (all suggested stronger immigration impacts on psychological distress for US citizen and permanent resident than for TPS and undocumented parents). Given concerns about a Type I error, we concluded that associations between immigration-related impacts and the odds of parents having high psychological distress were similar for Latino parents specifically targeted by official immigration actions and those not specifically targeted.

Disclosure of potential conflicts: There are no potential conflicts, real or perceived, for any authors of this study. The study sponsors had no role in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Authors’ contributions: K.M.R. conceptualized and designed the study, conducted analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript. E.V. conceptualized and designed the study, contributed to writing all manuscript sections, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript. R.M.B.W. conceptualized and carried out measurement work for immigration-related impacts, critically reviewed the survey instrument, contributed to writing some manuscript sections, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript. M.I.R. supervised and collected data, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Yee V. Immigrants hide, fearing capture on ‘any corner.’. [Accessed December 21, 2018];New York Times. 2017 Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/22/us/immigrants-deportation-fears.html.

- 2.Gorman A. Fear compromises the health, well-being of immigrant families, survey finds. [Accessed December 21, 2018];Washington Post. 2017 Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/fear-compromises-the-health-well-being-of-immigrant-families-survey-finds/2017/12/13/70405694-e018-11e7-b2e9-8c636f076c76_story.html?utm_term=.22980cd7e011.

- 3.White RMB, Updegraff KA, Umaña-Taylor AJ, et al. Neighborhood and school ethnic structuring and cultural adaptations among Mexican-origin adolescents. Dev Psychol. 2017;53:511–524. doi: 10.1037/dev0000269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cebulko K. Documented, undocumented, and liminally legal: Legal status during the transition to adulthood for 1. 5-generation. Brazilian immigrants Sociol Q. 2014;55:143–167. [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Citizenship and Immigration Services. [Accessed December 14, 2017];Temporary Protected Status. Available at: https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/temporary-protected-status. Updated November 11, 2017.

- 6.Cervantes RC, Padilla AM, Salgado de Snyder N. The Hispanic Stress Inventory: A culturally relevant approach to psychosocial assessment. Psychol Assess. 1991;3:438–447. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzales RG, Suárez-Orozco C, Dedios-Sanguineti MC. No place to belong: Contextualizing concepts of mental health among undocumented immigrant youth in the United States. Am Behav Sci. 2013;57:1174–1199. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arbona C, Olvera N, Rodriguez N, et al. Acculturative stress among documented and undocumented Latino immigrants in the United States. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2010;32:362–384. doi: 10.1177/0739986310373210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavazos-Rehg PA, Zayas LH, Spitznagel EL. Legal status, emotional well-being and subjective health status of Latino immigrants. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:1126–1131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rojas-Flores L, Clements ML, Hwang Koo J, London J. Trauma and psychological distress in Latino citizen children following parental detention and deportation. Psychol Trauma. 2017;9:352–361. doi: 10.1037/tra0000177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gulbas LE, Zayas LH, Yoon H, et al. Deportation experiences and depression among U.S. citizen-children with undocumented Mexican parents. Child Care Health Dev. 2016;42:220–230. doi: 10.1111/cch.12307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cobb CL, Meca A, Xie D, et al. Perceptions of legal status: Associations with psychosocial experiences among undocumented Latino/a immigrants. J Couns Psychol. 2017;64:167–178. doi: 10.1037/cou0000189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcini LM, Peña JM, Galvan T, et al. Mental disorders among undocumented Mexican immigrants in high-risk neighborhoods: Prevalence, comorbidity, and vulnerabilities. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2017;85:927–936. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abrego L, Coleman M, Martínez DE, et al. Making immigrants into criminals: Legal processes of criminalization in the post-IIRIRA era. J Migr Hum Secur. 2017;5:694–715. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siemons R, Raymond-Flesch M, Auerswald C, Brindis CD. Coming of age on the margins: mental health and wellbeing among Latino immigrant young adults eligible for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) J Immigr Minor Health. 2017;19:543–551. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0354-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raymond-Flesch M, Siemons R, Pourat N, et al. “There is no help out there and if there is, it’s really hard to find”: A qualitative study of the health concerns and health care access of Latino “DREAMers”. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhodes SD, Mann L, Simán FM, et al. The impact of local immigration enforcement policies on the health of immigrant Hispanics/Latinos in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:329–337. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshikawa H, Kalil A. The effects of parental undocumented status on the developmental contexts of young children in immigrant families. Child Dev Perspect. 2011;5:291–297. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Negi NJ. Battling discrimination and social isolation: psychological distress among Latino day laborers. Am J Community Psychol. 2013;51:164–174. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9548-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zapata Roblyer MI, Carlos FL, Merten MJ, et al. Psychosocial factors associated with depressive symptoms among Latina immigrants living in a new arrival community. J Lat Psychol. 2017;5:103–117. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conger RD, Conger KJ, Martin MJ. Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. J Marriage Fam. 2010;72:685–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wheeler LA, Updegraff KA, Crouter A. Mexican-origin parents’ work conditions and adolescents’ adjustment. J Fam Psychol. 2015;29:447–457. doi: 10.1037/fam0000085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menjívar C. Immigrant criminalization in law and the media: Effects on Latino immigrant workers’ identities in Arizona. Am Behav Sci. 2016;60:597–616. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dreby J. The burden of deportation on children in Mexican immigrant families. J Marriage Fam. 2012;74:829–845. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quiroga SS, Medina DM, Glick J. In the belly of the beast: Effects of anti-immigration policy on Latino community members. Am Behav Sci. 2014;58:1723–1742. [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Immigration and Customs Enforcement. [Accessed December 21, 2017];Fiscal year 2017 ICE enforcement and removal operations report. Available at: https://www.ice.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Report/2017/iceEndOfYearFY2017.pdf.

- 27.Acting Secretary Elaine Duke announcement on Temporary Protected Status for Haiti [news release] Washington, DC: US Department of Homeland Security; Nov 20, 2017. [Accessed December 21, 2017]. https://www.dhs.gov/news/2017/11/20/acting-secretary-elaine-duke-announcement-temporary-protected-status-haiti. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Acting Secretary Elaine Duke announcement on Temporary Protected Status for Nicaragua and Honduras [news release] Washington, DC: US Department of Homeland Security; Nov 20, 2017. [Accessed December 21, 2017]. https://www.dhs.gov/news/2017/11/06/acting-secretary-elaine-duke-announcement-temporary-protected-status-nicaragua-and. [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Department of Homeland Security. [Accessed December 21, 2017];Consideration of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) Available at: https://www.uscis.gov/archive/consideration-deferred-action-childhood-arrivals-daca.

- 30.Roosa MW, Liu FF, Torres M, et al. Sampling and recruitment in studies of cultural influences on adjustment: A case study with Mexican Americans. J Fam Psychol. 2008;22:293–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Derogatis LR. Symptom Checklist-90-Revised, Brief Symptom Inventory, and BSI-18. In: Maruish ME, editor. Handbook of Psychological Assessment in Primary Care Settings. 2. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2017. pp. 599–629. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torres L, Miller MJ, Moore KM. Factorial invariance of the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18) for adults of Mexican descent across nativity status, language format, and gender. Psychol Assess. 2013;25:300–305. doi: 10.1037/a0030436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Enriquez LM. Multigenerational punishment: Shared experiences of undocumented immigration status within mixed-status families. J Marriage Fam. 2015;77:939–953. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Messing JT, Becerra D, Ward-Lasher A, Androff DK. Latinas’ perceptions of law enforcement: Fear of deportation, crime reporting, and trust in the system. Affilia. 2015;30:328–340. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Meca A, Unger JB, et al. Longitudinal effects of Latino parent cultural stress, depressive symptoms, and family functioning on youth emotional well-being and health risk behaviors. Fam Process. 2017;56:981–996. doi: 10.1111/famp.12258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Capps R, Fix M, Zong J Migration Policy Institute. [Accessed December 21, 2017];A profile of U.S. children with unauthorized immigrant parents. Available at: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/profile-us-children-unauthorized-immigrant-parents.

- 37.Zayas LH, Bradlee MH. Exiling children, creating orphans: When immigration policies hurt citizens. Soc Work. 2014;59:167–175. doi: 10.1093/sw/swu004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The Economist Group Limited. Donald Trump is deporting fewer people than Barak Obama did. [Accessed January 26, 2018];The Economist. 2017 Available at: https://www.economist.com/news/united-states/21732561-deportation-has-also-become-considerably-more-random-donald-trump-deporting-fewer-people.

- 39.Ayón C, Valencia-Garcia D, Kim SH. Latino immigrant families and restrictive immigration climate: Perceived experiences with discrimination, threat to family, social exclusion, children’s vulnerability, and related factors. Race and Soc Probl. 2017;9:300–312. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshikawa H, Suárez-Orozco C, Gonzales RG. Unauthorized status and youth development in the United States: Consensus statement of the society for research on adolescence. J Res Adolesc. 2017;27:4–19. doi: 10.1111/jora.12272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]