Abstract

Introduction

An increasing proportion of the population is living into their nineties and beyond. These high risk patients are now presenting more frequently to both elective and emergency surgical services. There is limited research looking at outcomes of general surgical procedures in nonagenarians and centenarians to guide surgeons assessing these cases.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted of all patients aged ≥90 years undergoing elective and emergency general surgical procedures at a tertiary care facility between 2009 and 2015. Vascular, breast and endocrine procedures were excluded. Patient demographics and characteristics were collated. Primary outcomes were 30-day and 90-day mortality rates. The impact of ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) grade, operation severity and emergency presentation was assessed using multivariate analysis.

Results

Overall, 161 patients (58 elective, 103 emergency) were identified for inclusion in the study. The mean patient age was 92.8 years (range: 90–106 years). The 90-day mortality rates were 5.2% and 19.4% for elective and emergency procedures respectively (p=0.013). The median survival was 29 and 19 months respectively (p=0.001). Emergency and major gastrointestinal operations were associated with a significant increase in mortality. Patients undergoing emergency major colonic or upper gastrointestinal surgery had a 90-day mortality rate of 53.8%.

Conclusions

The risk for patients aged over 90 years having an elective procedure differs significantly in the short term from those having emergency surgery. In selected cases, elective surgery carries an acceptable mortality risk. Emergency surgery is associated with a significantly increased risk of death, particularly after major gastrointestinal resections.

Keywords: Nonagenarians, Emergency, Mortality, Outcomes, Surgery

There are over half a million people aged ≥90 years living in the UK.1 Despite representing only a small proportion of the population, this age group is growing rapidly and such patients are presenting more frequently with either acute or chronic conditions that require consideration for surgical intervention.

Difficult decisions need to be made in both elective and emergency situations; surgeons, patients and their families will need to jointly determine which individuals are likely to benefit from surgery and what risks they are willing to accept in undergoing a surgical procedure. Age and a trend to increasing co-morbidities will heavily influence the outcomes. However, high quality data looking specifically at outcomes of surgery in patients over 90 years of age is lacking.

Compounding this, predictors of surgical morbidity and mortality (specifically POSSUM [Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the enUmeration of Mortality and morbidity] and P-POSSUM [Portsmouth POSSUM], which are widely used as a risk assessment tool to identify poor surgical candidates) are not validated in this age group. Both scoring systems have been shown to overpredict morbidity and mortality in elderly patients.2 Alternatively, the E-POSSUM (Elderly POSSUM) has been suggested as a more accurate predictor of morbidity and mortality in those over 65 years of age although this has only been validated for patients undergoing major colorectal surgery.3

The aim of this study was to evaluate the outcomes of elective and emergency procedures in patients aged ≥90 years to help guide decision making, and to facilitate realistic discussions regarding outcomes with patients and their families.

Methods

All individuals aged ≥90 years undergoing both elective and emergency surgery at a large university teaching hospital between January 2009 and December 2015 were identified retrospectively using hospital theatre records. Only those admitted to the department of general surgery were included, and vascular, endocrine and breast procedures were excluded.

Data were collected from review of electronic records to determine basic demographic details such as age and sex as well as co-morbidities, ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) grade, mode of admission (elective vs emergency), length of procedure, grade of anaesthetist and surgeon, and type of anaesthesia. The postoperative outcomes studied included: planned/unplanned admission to critical care (high dependency or intensive care unit); return to theatre; 30-day, 90-day and 1-year mortality; and morbidity. In order to analyse outcomes according to the severity of the procedure, operations were categorised into three groups: ‘major+’ or ‘major’ (based on the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit [NELA] classification)4 and ‘other’ for operations not included in the NELA classification (Table 1).

Table 1.

Classification of severity of operations

| Major+ | Major | Other |

|

|

|

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS® version 20 (IBM, New York, US). Chi-squared and one-sample binomial tests were employed to compare survival rates. Multinomial regression was applied to identify any significant factors affecting mortality. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were used to describe survival and the statistical significance of differences was measured with the generalised Wilcoxon test (Breslow method).

Results

A total of 3,164 patients aged ≥90 years undergoing both elective and emergency procedures between January 2009 and December 2015 under all specialties were identified for possible inclusion in the study. Of these, 221 were admitted under general surgery, 970 under orthopaedic surgery, 455 under urology, 402 under plastic surgery, 979 under ophthalmology and 137 under other specialties.

Of the general surgery patients, 60 were admitted under subspecialties (breast, vascular or endocrine surgery) and were therefore excluded, leaving a total of 161 individuals for the analysis. Among the included cases, 58 (36%) were elective and 103 (64%) were emergency admissions. Table 2 summarises the basic demographic data of the patients as well as the ASA grade distribution in each group.

Table 2.

Patient demographics

| Characteristic | Elective (n=58) | Emergency (n=103) |

| Mean age | 92.5 (range: 90–102) | 92.9 (range: 90–106) |

| Sex | M=25 (43%), F=33 (57%) | M=38 (37%), F=65 (63%) |

| ASA grade 1 | 2 (3.4%) | 2 (1.9%) |

| ASA grade 2 | 26 (44.8%) | 23 (22.3%) |

| ASA grade 3 | 30 (51.7%) | 63 (61.2%) |

| ASA grade 4 | 0 (0%) | 15 (14.6%) |

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists

Looking specifically at the elective cases, the most commonly performed operation was inguinal hernia repair followed by the Delorme procedure. In this cohort, there were eight cancer related procedures including two anterior resections, three right hemicolectomies, one defunctioning colostomy, one ileocolic bypass and one abdominoperineal resection (Table 3).

Table 3.

Elective procedures performed

| Operation | n |

| Hernia repair (inguinal) | 26 (44.8%) |

| Delorme procedure | 12 (20.7%) |

| Colonic procedures | 8 (13.8%) |

| Other | 12 (20.7%) |

| Total | 58 (100%) |

The median length of hospital stay for elective patients was 2 days (interquartile range [IQR]: 1–6 days). There was no in-hospital mortality related to any elective procedure. The median survival was 29 months for elective versus 19 months for emergency cases (p=0.001). The 30-day mortality rate for elective operations was 0%, rising to 5.2% at 90 days and 15.5% at 1 year. The morbidity rate was 20.6%, the most common postoperative complication being urinary tract infection (5.2%). There was one unplanned admission to the high dependency unit and no returns to theatre. The majority (70.6%) of the elective procedures were carried out by a consultant surgeon.

In the emergency group, 34% of the operations were carried out by a consultant surgeon. The most frequently performed procedure was a laparotomy, accounting for 32% of the cases. The most common indication for laparotomy was small bowel resection (27.2%) followed by colostomy formation (15.5%), femoral hernia repair (12.6%) and inguinal hernia repair (10.7%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Emergency procedures performed

| Operation | n |

| Hernia repair (femoral) | 13 (12.6%) |

| Hernia repair (inguinal) | 11 (10.8%) |

| Laparotomy and resection of small bowel | 9 (8.7%) |

| Other laparotomy | 12 (11.7%) |

| Colostomy formation | 16 (15.5%) |

| Colonic procedures | 10 (9.7%) |

| Appendicectomy | 6 (5.8%) |

| Other | 26 (25.2%) |

| Total | 103 (100%) |

The median length of hospital stay for emergency patients was 14 days (IQR: 7–24 days). The 30-day mortality rate was 9.7%, increasing to 19.4% at 90 days and 28.1% at 1 year. Morbidity was common in this cohort, with 14.5% developing a lower respiratory tract infection and 12.6% developing a urinary tract infection in the postoperative period. A number of patients were admitted to a critical care unit following emergency surgery, with 11 planned and 4 unplanned postoperative admissions. One patient had to return to theatre for washout following a suspected anastomotic leak.

Table 5 summarises the outcomes in terms of 30 and 90-day and one year for elective versus emergency procedures. It should be noted that only two of the major operations were performed electively and so a comparison of the mortality rates for major surgery between elective and emergency cases is not meaningful.

Table 5.

Elective versus emergency outcomes

| n | 30-day mortality | 90-day mortality | 1-year mortality | Median survival | ||

| Elective | Major+ | 8 | 0% | 0% | 12.5% (n=1) | |

| Major | 2 | 0% | 0% | 50.0% (n=1) | ||

| Other | 48 | 0% | 6.3% (n=3) | 14.6% (n=7) | ||

| Overall | 58 | 0% | 5.2% (n=3) | 15.5% (n=9) | 29 mths | |

| Emergency | Major+ | 13 | 46.2% (n=6) | 53.8% (n=7) | 61.5% (n=8) | |

| Major | 43 | 7.0% (n=3) | 11.6% (n=5) | 20.9% (n=9) | ||

| Other | 47 | 2.1% (n=1) | 17.0% (n=8) | 25.5% (n=12) | ||

| Overall | 103 | 9.7% (n=10) | 19.4% (n=20) | 28.2% (n=29) | 19 mths | |

| All cases | 161 | 6.2% (n=10) | 14.3% (n=23) | 23.6% (n=38) |

Factors affecting 90-day and 1-year mortality

Univariate analysis was undertaken to assess the effect of ASA grade (1/2 vs 3/4), operation group (major+ vs major vs other) and mode of admission (elective vs emergency) on mortality at 90 days and 1 year (Table 6). Operation group and mode of admission had an effect on mortality at 90 days whereas ASA grade did not. At one year, the differences in mortality were no longer significant.

Table 6.

Univariate analysis of 90-day and 1-year mortality

| Comparison groups | p-value | |

| 90 days | 1 year | |

| ASA grade 1/2 vs 3/4 | 0.167 | 0.122 |

| Elective vs emergency | 0.011 | 0.105 |

| Operation group (major+ vs major vs other) | 0.020 | 0.072 |

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists

Multivariate analysis was performed to determine the impact of operation group and mode of admission. Analysis of 90-day mortality suggests that performing an emergency procedure is associated with an increased risk of death compared with elective cases (odds ratio [OR]: 3.6, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.5–21.4, p=0.009). Additionally, major+ operations are associated with a higher death rate than major (OR: 6.5, 95% CI: 1.7–25.6, p=0.007) and other procedures (OR: 3.6, 95% CI: 1.1–11.3, p=0.033).

Although there was a trend towards an increase in one-year mortality rates after emergency surgery compared with the elective cohort, this did not reach statistical significance (OR: 2.4, 95% CI: 1.0–5.9, p=0.057). Conversely, having a major+ operation still carried increased mortality risk at that time versus major (OR: 3.5, 95% CI: 1.1–11.2, p=0.035) and other procedures (OR: 2.8, 95% CI: 1.0–7.8, p=0.047).

Effects of different factors on long-term survival

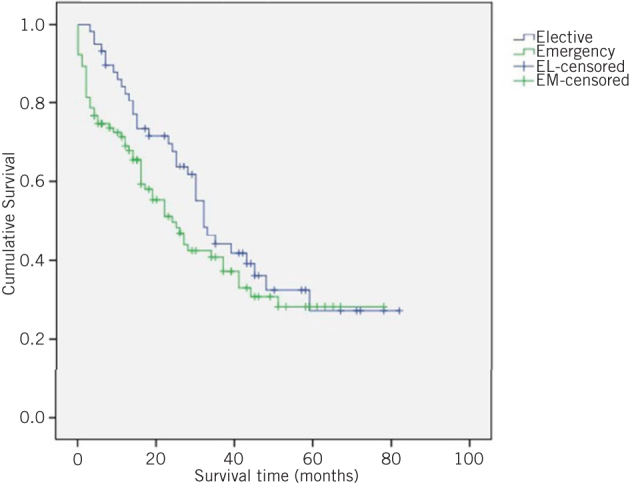

Kaplan–Meier curves show that a lower ASA grade (1/2) was associated with better long-term survival (p=0.006) (Fig 1). The difference between the three operative groups (p=0.032, Fig 2) and the two mode of admission groups (p=0.024, Fig 3) persisted for approximately five years.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve showing the effect of ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) grade on survival

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve showing the effect of operative group on survival

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve showing the effect of mode of admission on survival

Discussion

With the steady rise in life expectancy in the UK and the associated growth in the number of people living to 90 years and beyond, patients at the extremes of old age are increasingly presenting with surgical pathology. As these individuals often have significant co-morbidities and disability limiting quality of life, it can be difficult to determine which patients would see significant benefits from undergoing an operation given its potential substantial risk. Counselling patients and their families regarding risks and benefits is complex because it is difficult to prognosticate in this age group owing to the lack of data. However, a study from 2012 reported similar findings to our study in octogenarians undergoing emergency colonic surgery.5

When considering overall operative mortality (combining elective and emergency cases), our 30-day mortality rate was 6.2%, which is lower than that observed by Hosking et al at 8.4%.6 The 30-day mortality rate for emergency operations studied by Pelavski et al was 35.3%7 compared with 17.4% for emergency patients in the study by Hosking et al6 and 9.7% in our study.

Not surprisingly, the most striking differences in our data were noted when comparing elective and emergency surgery. The 30-day mortality rate for elective procedures in all operative categories was 0% versus 9.7% in the emergency cohort (p=0.014). The difference in outcome was even greater when considering mortality at 90 days (5.2% elective vs 19.4% emergency, p=0.013) and persisted even beyond that time (Fig 3).

Having an emergency procedure was also associated with more patients requiring higher level care in the postoperative period. There were 11 planned and 4 unplanned admissions to a critical care unit compared with only 1 admission for the elective cohort.

Complications and morbidity were higher for the emergency group (57.0% vs 13.7%), and these tended to be more serious. These findings are similar to rates observed for emergency cases by Hosking et al6 and Racz et al8 but our patients developed significantly fewer complications in the elective setting.

The overall outcomes in terms of mortality did not vary significantly according to the category of operation when looking at the elective patients except for the category of major procedures. On the other hand, that result is unreliable as only two individuals underwent major surgery in the elective setting.

When emergency cases were stratified according to operative severity, a significant difference became apparent between the outcomes, with those in the major+ group having a worse outcome than both other groups. Almost half (46.2%) of the patients who underwent a major+ procedure died within 30 days. The mortality rate rose to 53.8% at 90 days and 61.5% at 1 year. There was a significant difference in overall median survival compared with patients who required less severe operations. Those undergoing major surgery had mortality rates increase from 7.0% at 30 days to 11.6% at 90 days and 20.9% at 1 year while other procedures had mortality rates increase from 2.1% to 17.0% to 25.5% respectively.

A one-year mortality rate of over 20% is a serious issue. The rise in mortality over time could suggest that the perceived benefit of surgery might not be as prolonged as initially hoped. This calls into question the value of surgical intervention for these cases.

Among those individuals who underwent an elective procedure for colorectal cancer, the 30-day mortality rate was 0%. This contrasts with 20% observed by Damhuis et al9 and 23.8% by Warner et al.10 However, their analysis combined elective and emergency operations. In our series, the one-year mortality rate for all patients undergoing colorectal resection was 25.0%, with all mortalities occurring within 30 days. There was one unplanned return to theatre among the emergency colorectal surgery cases (for washout following a suspected anastomotic leak) although the patient is alive five years on from surgery.

One of the most difficult aspects of deciding whether an individual should undergo any type of surgical intervention is determining whether he or she will benefit from the procedure, or whether it may actually cause harm or prolong suffering unnecessarily when there is no remaining quality of life. Our study did not look at whether patients returned to their functional baseline or even improved following surgery. This makes it difficult to comment on the overall benefit of surgical intervention beyond simply measuring mortality and morbidity. The majority of surgeons believe that prolonging the life of a patient with poor functional/mental capacity serves no purpose, and this issue is commonly at the forefront of a decision of surgeons, patients and families not to proceed with surgery.

Even in individuals with relatively few co-morbidities, these patients still have a relatively limited life expectancy, with a 90-year-old woman in England expected to live a further 4.50 years and a man 3.94 years.11 The decision to operate on anyone aged over 90 years should take into account not only the outcomes presented in this paper but also the very limited life expectancy of these patients. In fact, the surgeon should also consider patient factors, the nature of the procedure itself and the operative setting as well as the life expectancy.

Simply comparing the numbers in the two groups (elective vs emergency) shows that there are many more patients being operated on in an emergency setting, which raises questions that this study cannot answer but that should be considered. Reasons for this difference may include general practitioners being less likely to make a surgical referral for elderly patients with non-life threatening conditions. Moreover, once seen in clinic, surgeons may take a more conservative approach given the fact that elderly patients are likely to have significant co-morbidities and a limited lifespan. The decision in emergency cases is often one of life or death. In these circumstances, patients, their families and the operating surgeon may be willing to accept a higher level of risk, irrespective of whether this is necessarily the right thing to do.

Study limitations

One of the limitations of this study is that only individuals who actually underwent any type of surgical intervention were included. There are no data regarding the number and nature of surgical referrals that did not result in an operation. It is likely that the number of referrals is significant as a study by Toumi et al found that only 2% of surgical referrals for patients aged over 90 years with a suspected acute abdomen resulted in an operation.12 Furthermore, our study did not consider functional outcomes, or look at what proportion of patients were able to return to their baseline functional status or level of independence in the postoperative period.

Conclusions

Overall, the 90-day observed mortality rate for all patients undergoing either an elective or emergency procedure at our institution was 14.3%, rising to 23.2% at 1 year. Considering the benefits of surgery, some patients and their families would feel this to be an acceptable risk. Nevertheless, these figures can change significantly depending on the type and setting of the operation. Major abdominal surgery in an emergency setting carries with it a high morbidity whereas elective procedures in carefully risk assessed individuals appear to be successful in the vast majority of cases.

Patient selection and identification of those who will likely benefit from surgery is difficult in the elderly owing to the combination of multiple co-morbidities and the general decreased physiological reserve associated with ageing. As highlighted in the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death report on surgery in the elderly, identification of frailty is a key factor in case selection.13 Frailty should be considered an independent risk factor for poor surgical outcomes. However, assessment of frailty is in itself difficult. Clear and frank information about the significant risks associated with surgery in elderly patients must be discussed with patients and their families to help set realistic expectations.

References

- 1.Office for National Statistics Estimates of the very old (including centenarians), UK: 2002 to 2015. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/ageing/bulletins/estimatesoftheveryoldincludingcentenarians/2002to2015 (cited October 2017).

- 2.Wakabayashi H, Sano T, Yachida S et al. Validation of risk assessment scoring systems for an audit of elective surgery for gastrointestinal cancer in elderly patients: an audit. 2007; : 323–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tran Ba Loc P, du Montcel ST, Duron JJ et al. Elderly POSSUM, a dedicated score for prediction of mortality and morbidity after major colorectal surgery in older patients. 2010; : 396–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.. London: NELA; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Modini C, Romagnoli F, De Milito R et al. Octogenarians: an increasing challenge for acute care and colorectal surgeons. An outcomes analysis of emergency colorectal surgery in the elderly. 2012; : e312–e318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hosking MP, Warner MA, Lobdell CM et al. Outcomes of surgery in patients 90 years of age and older. 1989; : 1,909–1,915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pelavski AD, Lacasta A, Rochera MI et al. Observational study of nonogenarians undergoing emergency, non-trauma surgery. 2011; : 189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Racz J, Dubois L, Katchky A, Wall W. Elective and emergency abdominal surgery in patients 90 years of age or older. 2012; : 322–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damhuis RA, Meurs CJ, Meijer WS. Postoperative mortality after cancer surgery in octogenarians and nonagenarians: results from a series of 5,390 patients. 2005; : 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warner MA, Hosking MP, Lobdell CM et al. Surgical procedures among those greater than or equal to 90 years of age. A population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1975–1985. 1988; : 380–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Office for National Statistics England, national life table, 2015. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/lifeexpectancies/adhocs/006157englandnationallifetable2015 (cited October 2017).

- 12.Toumi Z, Kesterton A, Bhowmick A et al. Nonagenarian surgical admissions for the acute abdomen: who benefits? 2010; : 1,570–1,572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death . London: NCEPOD; 2010. [Google Scholar]