Abstract

Introduction

While preoperative chemotherapy is frequently utilized prior to resection of non-neuroendocrine liver metastases, patients with resectable neuroendocrine liver metastases typically undergo surgery first. FAS is a cytotoxic chemotherapy regimen that is associated with substantial response rates in locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors.

Methods

All patients who underwent R0/R1 resection of pancreatic neuroendocrine liver metastases at a single institution between 1998 and 2015 were included. The outcomes of patients treated with preoperative FAS were compared to those of patients who were not.

Results

Of the 67 patients included, 27 (40.3%) received preoperative FAS while 40 (59.7%) did not. Despite being associated with higher rates of synchronous disease, lymph node metastases, and larger tumor size, patients who received preoperative FAS had similar overall survival (OS, 108.2 months [95% CI 78.0-136.0] vs 107.0 months [95% CI 78.0-136.0], p=0.64) and recurrence-free survival (RFS, 25.1 months [95% CI 23.2-27.0] vs 18.0 months [95% CI 13.8-22.2], p=0.16) as patients who did not. Among patients who presented with synchronous liver metastases (n=46), the median OS (97.3 months [95% CI 65.9-128.6] vs 65.0 months [95% CI 28.1-101.9], p=0.001) and RFS (24.8 months [95% CI 22.6-26.9] vs 12.1 months [2.2-22.0], p=0.003) were significantly greater among patients who received preoperative FAS compared to those who did not.

Conclusions

The use of FAS prior to liver resection is associated with improved OS compared to surgery alone among patients with advanced synchronous pancreatic neuroendocrine liver metastases.

Introduction

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNET) are heterogeneous in both their clinical presentation and behavior1. Although the clinical course of low and intermediate grade pNETs is believed to be indolent, as many as 40% of patients with pNETs will develop neuroendocrine liver metastases (NELM) during their lifetime2. Although the presence of liver metastases is one of the strongest negative prognostic indicators in patients with pNET, surgical resection of NELM, when possible, is associated with a significant survival benefit3,4. In fact, a meta-analysis reported a pooled median 5 year overall survival (OS) rate of 71% in patients who underwent liver resection and >95% experienced symptomatic relief5. Other liver-directed therapies include radiofrequency ablation, transarterial embolic therapy, and most recently, peptide receptor radionuclide therapy, but liver resection is typically associated with the best long term outcomes and is considered the first choice for management of NELM6.

Most patients with liver metastases of non-neuroendocrine origin receive multimodality therapy that includes systemic chemotherapy as a component of the treatment strategy. The aims of preoperative chemotherapy include the potential to stimulate tumor downstaging, the opportunity to assess response of the tumor to therapy, and to ensure stable tumor biology prior to undergoing major surgery. In patients with advanced colorectal liver metastases, for example, the combination of perioperative 5-flourouracil (5-FU) based chemotherapy and liver resection at experienced centers is associated with excellent survival outcomes7,8. Furthermore, perioperative systemic chemotherapy is frequently used prior to liver resection in other cancers as well in order to select for patients with disease stability and improve survival rates9. However, a similar role for preoperative chemotherapy in NELM secondary to pNETs has not been previously reported.

Streptozocin was the first therapy approved for patients with advanced or symptomatic pNET10. Since then, investigators have reported on its improved efficacy when combined with 5-FU11 and doxorubicin12. At the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, we have observed response rates of over 40% among patients with locally advanced and metastatic pNET when treated with combination 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin and streptozocin (FAS)13,14. Recently, we evaluated our experience with preoperative FAS in patients with non-metastatic locally advanced well-differentiated pNETs and found that FAS was infrequently associated with significant tumor downstaging suggesting differential effects of chemotherapy on the primary vs metastatic tumors15. The role of preoperative FAS in patients with advanced NELM, with or without the primary pNET in situ, has not been previously explored. Within this context, we set out to evaluate the influence of preoperative FAS on the outcomes of patients with pancreatic NELM who underwent liver resection.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Patients Selection

The Institutional Review Board of MD Anderson Cancer Center approved this retrospective study (PA17-0318). From a prospectively maintained database, we included all patients who underwent liver resection for NELM of pancreatic origin between January 1998 and December 2015, with follow-up through March 2017. Patients who underwent macroscopically positive resection (n=3) were excluded.

Next, we evaluated all patients with advanced metastatic pNET who received treatment with FAS at our institution without undergoing hepatectomy. After excluding patients with extrahepatic metastases (n=110) and those in whom macroscopically negative resection was not possible using modern hepatectomy strategies (n=74), we identified a cohort of patients with potentially resectable NELM treated non-operatively with FAS and other therapies. All patients were ≥18 years of age, had an Eastern Cooperative Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 to 1 with adequate hepatic, renal and bone marrow function for potential liver resection.

Chemotherapy Regimen

FAS included an intravenous 400 mg/m2 bolus of 5-FU and an intravenous 400 mg/m2 bolus of streptozocin on days 1–5 as well as 40 mg/m2 intravenous bolus of doxorubicin on day 1 with each cycle repeated every 28 days. The typical objective was treatment to maximal radiographic response, unacceptable toxicity or patient intolerance14,15. Drug toxicities were monitored closely, with modifications and dose adjustments made as necessary for laboratory abnormalities (hyperbilirubinemia at the beginning of therapy or uncontrolled diabetes mellitus in the case of streptozocin); reduction in cardiac function (for doxorubicin) or any other grade 3, 4 toxicities while on therapy. Occasionally, grade 1 or 2 toxicities led to dose reduction or to delay of the treatment. Following preoperative FAS chemotherapy, patients were re-staged with CT or MRI. Tumor markers, bone scans and somatostatin scintigraphy were obtained as needed and surgical resection was offered to those for whom margin-negative hepatic resection was considered achievable. Adjuvant systemic therapy was not routinely administered following surgical resection.

Review of Patient Records

The following factors were retrieved from the database: sex, age, body mass index, number of tumors, largest diameter of the tumor, distribution, lymph node metastasis, clinical stage, tumor grade, Ki-67 index (from liver metastasis), extent of hepatectomy, and long-term outcomes. OS was measured from the date of initial treatment (preoperative chemotherapy or surgical resection) until the date of death or last follow-up. Recurrence free survival (RFS) was measured from the date of surgery until the date of radiographic detection of recurrence or last follow-up. Laboratory data, tumor number and size were evaluated prior to FAS chemotherapy or surgery when patients were treatment-naive. Clinical stage was based on the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging manual16. Major resection was defined as hepatic resection including 3 or more segments. Postoperative morbidities were reviewed based on Clavien-Dindo classification17. Complications classified as grade III or higher were defined as major.

Statistical Analyses

First, the clinicopathologic characteristics and survival outcomes of patients who received FAS prior to undergoing liver resection were compared to those of patients who underwent liver resection without preoperative FAS. Next, we performed a subset analysis of only patients who presented with synchronous liver metastases with primary pNETs in situ. Finally, the patients who underwent surgical resection with or without preoperative FAS, were compared to a cohort of patients with potentially resectable liver metastases who received FAS without surgical resection.

Continuous variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test while categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between curves were evaluated with the log-rank test. All test were two-side, and P<0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed with JMP software (version 12.1.0; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

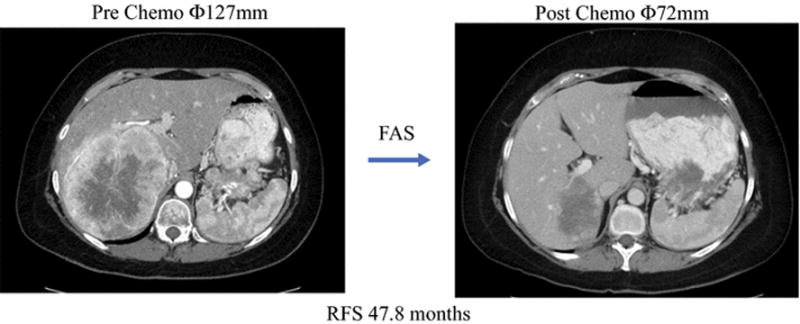

Of the 67 patients with pancreatic NELM who underwent surgical resection between 1998 and 2015, 27 (40.3%) received preoperative FAS while 40 (59.7%) did not. Of the 40 patients who did not receive preoperative FAS, 31 received upfront surgical resection while 9 received another preoperative chemotherapy regimen (doxorubicin-streptozocin, 5-FU-gemcitabine, 5-FU-streptozocin, bleomycin-epirubicin-cisplatin, 5-FU-oxaliplatin-bevacizumab, temazolomide-capecitabine, temazolomide, paclitaxel, and irinotecan-cisplatin) followed by surgical resection. The median number of cycles of FAS administered prior to surgery was 4 (range 2-13). Seventeen patients (63.0%) experienced a partial response (PR) according to RECIST criteria (Figure 1), whereas 8 (29.6%) had stable disease and 2 (7.4%) had progressive disease. Among the 16 patients who had synchronous disease and experienced a PR in their liver metastases, only 7 (43.8%) demonstrated a PR in their primary pNET while 9 (56.3%) had stable disease. Of the 27 patients who received FAS prior to surgery, 22 (81.5%) were resectable prior to preoperative chemotherapy and 5 (18.5%) were initially unresectable but became resectable after preoperative FAS.

Figure 1.

Representative images demonstrating partial response of neuroendocrine liver metastasis to preoperative FAS chemotherapy

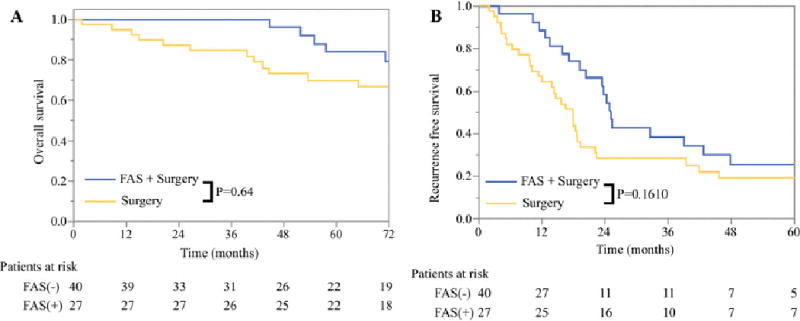

The clinicopathologic and operative characteristics of all patients who underwent surgical resection are listed in Table 1. Patients who received preoperative FAS were significantly more likely to present with synchronous disease (92.6% vs 45.0%, p<0.001), had a larger maximum metastasis diameter (3.9cm vs 2.1cm, p<0.001), were more likely to have positive lymph nodes (74.8% vs 40.0%, p<0.05), and had higher rates of somatostatin analog use prior to surgery (100.0% vs 5.0%, p<0.001). However, despite these poor prognostic features, there were no significant difference in the rate of microscopically positive resection, major postoperative complications, OS (108.2 months [95% CI 78.0-136.0] vs 107.0 months [95% CI 78.0-136.0], p=0.64) or RFS (25.1 months [95% CI 23.2-27.0] vs 18.0 months [95% CI 13.8-22.2], p=0.16) among patients who received preoperative FAS compared to those who did not (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics and outcomes of patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine liver metastases

| Surgical Cohort | Medical Cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients (n=67) |

No Preoperative FAS (n=40) |

Preoperative FAS (n=27) |

P value1 | All Patients (n=24) |

P value2 | |

| Gender (M: F) | 38:29 | 20:20 | 18:9 | 0.174 | 15:9 | 0.668 |

| Median Age, years (range) | 56 (11–76) | 56 (11–76) | 52(29–74) | 0.944 | 60 (42–76) | 0.133 |

| Median Body mass index (kg/m2) (range) | 26.4(13.5–46.5) | 25.9(13.5–46.5) | 27.5 (18.7–41.3) | 0.402 | 28 (19–51) | 0.919 |

| Number of tumors, Solitary/Multiple/Range | 28/39/1–15 | 16/24/1–15 | 12/15/1–10 | 0.718 | 3/21/1–11 | 0.010 |

| Median Size of Largest Tumor, mm (range) | 31 (3–127) | 21 (3–121) | 36 (10–127) | 0.001 | 42 (10–152) | 0.003 |

| Synchronous / Metachronous | 46/21 | 20/20 | 26/1 | <.0001 | 20/4 | 0.114 |

| Bilateral tumor location | 23 (34%) | 11 (28%) | 12 (44%) | 0.153 | 19 (79%) | 0.016 |

| Grade G1/G2/G3/unknown | 25/17/4/21 | 16/6/4/14 | 9/11/0/7 | 0.062 | 18/3/0/3 | 0.012 |

| Median Ki 67 Index (range) | 5.8 (1–35) | 10 (1–35) | 5 (1.9–20) | 0.359 | 6 (2–10) | 0.531 |

| Major resection | 15 (22%) | 9 (23%) | 6 (22%) | 0.979 | N/A | |

| Resection with RFA | 11 (16%) | 8 (21%) | 3 (11%) | 0.304 | ||

| R1 resection | 15 (22%) | 7 (18%) | 8 (30%) | 0.269 | ||

| Major postoperative complications | 19 (28%) | 12 (30%) | 7 (26%) | 0.716 | ||

| Primary T stage, T1/T2/T3/T4/unknown | 2/9/48/1/7 | 1/8/24/1/6 | 1/1/24/0/1 | 0.089 | ||

| Primary N stage, N0/N1/unknown | 26/35/6 | 19/16/5 | 7/19/1 | 0.031 | ||

Results are number (%) unless otherwise mentioned.

p Value comparing patients who FAS + surgery versus no FAS + surgery;

Comparison of patients who received FAS + surgery versus FAS alone

Figure 2.

A) Overall and B) Recurrence-free survival among patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine liver metastases based on whether FAS was administered prior to surgical resection

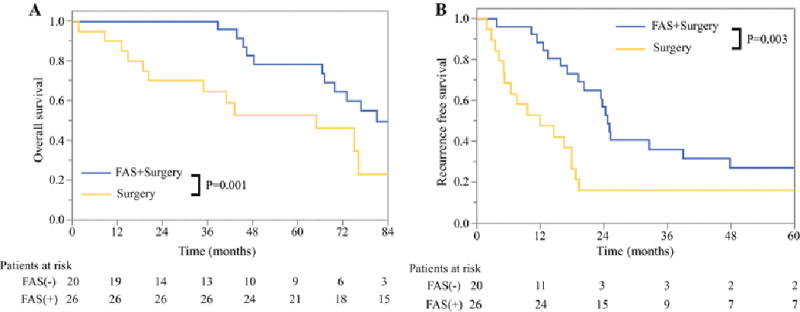

Among the 46 patients who presented with synchronous liver metastases along with an intact primary pNET, 26 underwent preoperative FAS prior to surgical resection whereas 20 did not. Resections were synchronous in 35 (76.1%) and staged in 11 (23.9%). The clinicopathologic and operative characteristics of the two groups were similar except patients who received preoperative FAS were more likely to have a higher primary tumor T-stage (Supplementary Table). The median OS (97.3 months [95% CI 65.9-128.6] vs 65.0 months [95% CI 28.1-101.9], p=0.001) and RFS (24.8 months [95% CI 22.6-26.9] vs 12.1 months [2.2-22.0], p=0.003) was significantly greater among patients with synchronous NELM who received preoperative FAS compared to those who did not (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A) Overall and B) Recurrence-free survival among patients with synchronous pancreatic neuroendocrine liver metastases based on whether FAS was administered prior to surgical resection

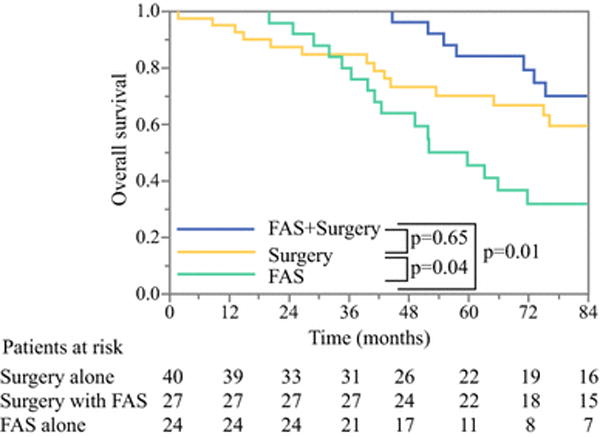

Twenty-four patients were retrospectively identified as having potentially resectable pancreatic NELM but were treated with FAS and did not undergo liver resection (Table 1). For all patients, FAS was first-line therapy and the median number of cycles received was 5 (range 1-13). The majority of patients (79.2%) had their primary tumor in situ. Patients who received FAS alone were less likely to have a solitary liver metastasis compared to patients who underwent FAS and surgery as well as surgery alone (12.5% vs 44.4% vs 40.0%, p<0.05). The median size of the largest metastasis was 3.5cm (range 1.0-8.2cm). Reasons for not undergoing surgical resection were absence of documented consultation with a hepatobiliary surgeon (58.3%), locally advanced primary pNET (12.5%), concern for older age or comorbidities (8.3%), progressive disease on therapy (4.2%), complete radiographic response (4.2%), and reasons not ascertainable by retrospective review of the medical chart (16.7%). Seven of 24 patients’ (29.2%) liver metastases exhibited a PR following FAS. Among these 7 patients, the primary pNET demonstrated a PR in 2 patients (28.6%) and SD in 5 patients (71.4%). The median OS duration of patients who received FAS alone without liver resection was significantly lower than that of patients who received FAS prior to surgery (59.6 months [95% CI 42.5-76.8] vs 108.2 months [95% CI 73.2-143.2], p=0.01) or of patients who did not receive FAS prior to resection (59.6 months [95% CI 42.5-76.8] vs 107.0 months [95% CI 78.0-136.0], p=0.04); Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Overall survival among patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine liver metastases treated with FAS and surgery (green), surgery without FAS (red), or FAS without surgery (blue).

DISCUSSION

Although the management of resectable liver metastases in other malignancies often involves a short course of preoperative systemic chemotherapy to ensure disease stability, allow for potential tumor downstaging and monitor the response to therapy, most patients with resectable NELM are offered upfront surgical resection. This may be related to the lack of data available on effective neoadjuvant treatment strategies for patients with NELM. To that end, our study, albeit retrospective, represents one of the first to demonstrate the potential efficacy of a preoperative regimen for patients with potentially resectable pancreatic NELM who present with advanced disease. Specifically, our study has several pertinent findings. First, among patients included in this retrospective study who underwent resection, the response rate of pancreatic NELM to FAS was approximately 63%. Second, despite more aggressive clinical and biological characteristics, patients who underwent FAS prior to surgical resection had similar OS and RFS compared to patients who underwent surgery first without any increase in the incidence of major post-operative complications. Third, among patients with synchronous liver metastases, preoperative FAS was associated with a significant OS and RFS survival benefit. Finally, when compared to patients treated with FAS alone for potentially resectable liver metastases, those who underwent liver resection after FAS had significantly better OS.

The combination of streptozocin with doxorubicin is a common therapeutic regimen for patients with metastatic or advanced pNET based on the results of a series of randomized controlled trials from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group11,12. However, our institution has preferentially used the triple chemotherapy regimen of 5-FU, doxorubicin and streptozocin which has resulted in response rates as high as 55% in previous reports14; moreover, these responses are fairly durable with the median duration of tumor response nearly 10 months in one series13. Interestingly, the response rate in this cohort of patients with metastatic disease confined to the liver and eventually selected for liver resection was an impressive 63%. This is especially striking given our recent finding that FAS was associated with only a partial response rate of 7% when used as preoperative therapy for locally advanced primary pNET15. Even in the current study, the primary pNET demonstrated a response to FAS less often than the liver metastases. Why this treatment strategy appears more efficacious for the hepatic disease is unknown but given the prognostic importance of liver metastases (and their resectability) on survival in patients with pNET5,18, identification of an effective treatment regimen that facilitates surgical resection is critically important.

Although there is limited data on the use of preoperative chemotherapy for pNETs15,19, there are increasing reports on the use of preoperative PRRT for locally advanced or unresectable PNETs20–23. Even fewer reports are available on the use of preoperative therapy for NELM24, although clearly there is interest in identifying effective neoadjuvant treatment strategies for this unique population of patients25,26. It is noteworthy that most of the previously published case reports and small case series’ aim was facilitation of resectability, whereas our results with preoperative FAS in this study suggest the potential for improved OS and RFS, especially in those patients with synchronous disease.

Although the results of this study are novel and potentially impactful, they should be interpreted within the context of their limitations. First, this is a single-institution, retrospective study in which treatment decisions were not made randomly. Because of its retrospective nature, we were unable to reliably identify those patients who initiated FAS with preoperative intent but failed to undergo liver resection. Similarly, we were unable to assess via retrospective chart review whether patients in the FAS alone group were treated with a preoperative intent (but failed to undergo surgery) or were being treated with definitive chemotherapy. This inability to define a true “denominator” allows for a selection bias in the analysis of the final group of patients who received FAS prior to surgery. Second, while we retrospectively confirmed that the FAS alone patients were anatomically resectable in order to grossly match tumor characteristics to the other cohorts, other equally important factors affecting resectability (e.g. patient comorbidities or performance status, tumor biology, patient preference, etc) and unmeasured factors could not be retrospectively assessed but likely differed between groups. Third, some patients in the non-preoperative FAS groups received alternate preoperative chemotherapy regimens. However, the purpose of the study was to evaluate the impact of preoperative FAS not any preoperative therapy, and the inclusion of these patients in the control group might be hypothesized to minimize, not amplify, any survival differences. Fourth, this study does not have pathologic data available to measure tumor response to therapy. Finally, given its retrospective nature, this study did not assess toxicities of the preoperative regimen though this would be expected to be consistent with previous reports13.

In summary, pancreatic NELM demonstrate excellent response rates to FAS. The use of FAS prior to liver resection was associated with improved OS compared to surgery alone among patients with synchronous metastases as well improved OS compared to FAS alone without surgical resection. We conclude that patients with pancreatic NELM should be evaluated upfront in a multi-disciplinary setting where multimodality treatment decisions can be made collectively before treatment sequencing decisions are finalized, and that preoperative FAS could be considered for patients with advanced synchronous pancreatic NELM.

Supplementary Material

Synopsis.

Between 1998-2015, 67 patients underwent R0/R1 resection of pancreatic neuroendocrine liver metastases (NELM). Patients who received preoperative 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin and streptozocin (FAS) experienced similar OS and RFS as patients who did not despite greater lymph node metastases and larger size; whereas, the use of preoperative FAS was associated with improved OS and RFS among the subset of patients with synchronous disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to recognize Ms. Ruth Haynes for administrative support in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: None of the authors have any conflicts of interest associated with this study.

References

- 1.Cloyd JM, Poultsides GA. Non-functional neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas: Advances in diagnosis and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(32):9512–9525. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i32.9512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97(4):934–959. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Touzios JG, Kiely JM, Pitt SC, et al. Neuroendocrine hepatic metastases: does aggressive management improve survival? Ann Surg. 2005;241(5):776–783. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000161981.58631.ab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayo SC, de Jong MC, Bloomston M, et al. Surgery versus intra-arterial therapy for neuroendocrine liver metastasis: a multicenter international analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(13):3657–3665. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1832-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saxena A, Chua TC, Perera M, Chu F, Morris DL. Surgical resection of hepatic metastases from neuroendocrine neoplasms: a systematic review. Surg Oncol. 2012;21(3):e131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fairweather M, Swanson R, Wang J, et al. Management of Neuroendocrine Tumor Liver Metastases: Long-Term Outcomes and Prognostic Factors from a Large Prospective Database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017 Mar; doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5839-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brouquet A, Abdalla EK, Kopetz S, et al. High survival rate after two-stage resection of advanced colorectal liver metastases: response-based selection and complete resection define outcome. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2011;29(8):1083–1090. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.6132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ, et al. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2009;27(22):3677–3683. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martel G, Hawel J, Rekman J, et al. Liver resection for non-colorectal, non-carcinoid, non-sarcoma metastases: a multicenter study. PloS One. 2015;10(3):e0120569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broder LE, Carter SK. Pancreatic islet cell carcinoma. II. Results of therapy with streptozotocin in 52 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1973;79(1):108–118. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-79-1-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moertel CG, Hanley JA, Johnson LA. Streptozocin alone compared with streptozocin plus fluorouracil in the treatment of advanced islet-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(21):1189–1194. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198011203032101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moertel CG, Lefkopoulo M, Lipsitz S, Hahn RG, Klaassen D. Streptozocin-doxorubicin, streptozocin-fluorouracil or chlorozotocin in the treatment of advanced islet-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(8):519–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202203260804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kouvaraki MA, Ajani JA, Hoff P, et al. Fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and streptozocin in the treatment of patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic endocrine carcinomas. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2004;22(23):4762–4771. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rivera E, Ajani JA. Doxorubicin, streptozocin, and 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy for patients with metastatic islet-cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 1998;21(1):36–38. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199802000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prakash L, Bhosale P, Cloyd J, et al. Role of Fluorouracil, Doxorubicin, and Streptozocin Therapy in the Preoperative Treatment of Localized Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. J Gastrointest Surg Off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract. 2017;21(1):155–163. doi: 10.1007/s11605-016-3270-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edge S, Byrd D, Compton C. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien P-A. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chu QD, Hill HC, Douglass HO, et al. Predictive factors associated with long-term survival in patients with neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9(9):855–862. doi: 10.1007/BF02557521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devata S, Kim EJ. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with capecitabine and temozolomide for unresectable pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. Case Rep Oncol. 2012;5(3):622–626. doi: 10.1159/000345369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaemmerer D, Prasad V, Daffner W, et al. Neoadjuvant peptide receptor radionuclide therapy for an inoperable neuroendocrine pancreatic tumor. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(46):5867–5870. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sowa-Staszczak A, Pach D, Chrzan R, et al. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy as a potential tool for neoadjuvant therapy in patients with inoperable neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38(9):1669–1674. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1835-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Vliet EI, van Eijck CH, de Krijger RR, et al. Neoadjuvant Treatment of Nonfunctioning Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors with [177Lu-DOTA0,Tyr3]Octreotate. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 2015;56(11):1647–1653. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.158899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ezziddin S, Lauschke H, Schaefers M, et al. Neoadjuvant downsizing by internal radiation: a case for preoperative peptide receptor radionuclide therapy in patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Nucl Med. 2012;37(1):102–104. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e318238f111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoeltzing O, Loss M, Huber E, et al. Staged surgery with neoadjuvant 90Y-DOTATOC therapy for down-sizing synchronous bilobular hepatic metastases from a neuroendocrine pancreatic tumor. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2010;395(2):185–192. doi: 10.1007/s00423-009-0520-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sowa-Staszczak A, Hubalewska-Dydejczyk A, Tomaszuk M. PRRT as neoadjuvant treatment in NET. Recent Results Cancer Res Fortschritte Krebsforsch Progres Dans Rech Sur Cancer. 2013;194:479–485. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-27994-2_27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perysinakis I, Aggeli C, Kaltsas G, Zografos GN. Neoadjuvant therapy for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: an emerging treatment modality? Horm Athens Greece. 2016;15(1):15–22. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.