Abstract

Commercial fungal cellulases used in biomass-to-biofuels processes can be grouped into three general classes: native, augmented, and engineered. Colorimetric assays for general glycoside hydrolase activities showed distinct differences in enzyme binding to lignin for each enzyme activity. Native cellulase preparations demonstrated low binding of endo- and exocellulases, high binding of xylanase, and moderate binding for β-D-glucosidases. Engineered cellulase formulations exhibited low binding of exocellulases, very strong binding of endocellulases and β-D-glucosidase, and mixed binding of xylanase activity. The augmented cellulase had low binding of exocellulase, high binding of endocellulase and xylanase, and moderate binding of β-D-glucosidase activities. Bound and unbound activities were correlated to general molecular weight ranges of proteins as measured by loss of proteins bands in bound fractions on SDS-PAGE gels. Lignin-bound high molecular weight bands correlated to binding of β-D-glucosidase activity. Whereas β-D-glucosidases demonstrated high binding in many cases, they have been shown to remain active. Bound low molecular weight bands correlated to xylanase activity binding. Contrary to other literature, exocellulase activity did not show strong lignin binding. The variation in enzyme activity binding between these three classes of cellulases preparations indicates that it is possible to alter the binding of specific glycoside hydrolase activities during the enzyme formulation process. It remains unclear whether or not loss of endocellulase activity to lignin binding is problematic for biomass conversion.

Keywords: Lignin, protein binding, cellulase, β-D-glucosidase, xylanase

Introduction

It has been well established that overall lignin content and its localized distribution post-pretreatment are factors limiting enzymatic hydrolysis efficiencies in commercial biomass-to-biofuels processes [1–4]. Temperatures above 140°C permit lignin to attain its glass transition phase, resulting in its separation and migration from the carbohydrate polymers of the cell wall. Lignin droplets of various sizes appear on cell wall surfaces after thermochemical pretreatment, as verified by antibody and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDAX) SEM and TEM analysis, where a clear correlation was found between thermochemical pretreatment severities and the size and number of surface lignin droplets [5]. The presence of these droplets may decrease the rate of enzymatic saccharification, either by physically blocking access of cellulases to cellulose microfibrils or by increased non-productive adsorption of enzymes [5].

Complete removal of lignin from the plant cell wall is cost prohibitive for biofuels production and results in an overall increase in cellulose crystallinity, corresponding to a reduction in its digestibility [6, 7]. Nakagame et. al. determined the major variables resulting in non-productive adsorption of hydrolytic enzymes to lignin [8–10]. They showed that lignin from different plant origins coupled with varied pretreatment chemistries and severities may result in a variable adsorption surface chemistry and enzyme accessibility [9, 10]. They developed potential pretreatment strategies that may alter lignin surface chemistries to effectively keep enzymes from adsorbing to the surface of lignin under process relevant pH and ionic strength conditions. Other groups have worked to modify the surface chemistry of lignin to reduce its affinity toward enzymes. Lou and et al. used sulfite pretreatment revealing that pH-induced lignin surface modification reduces the non-specific, cellulase binding to lignin and enhances enzymatic saccharification at elevated pH (i.e., pH 5.5 and higher) [11].

There are many evolving hypotheses and approaches regarding non-productive adsorption of cellulases and hemicellulases to lignin. It is generally accepted that enzyme-lignin interactions are non-covalent and likely due to hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions, and possibly hydrogen bonding and charge transfer effects, such as pi-orbital electron interactions [12]. These assumptions have led to several research groups focusing on single enzyme types and families to measure specific enzyme adsorption rates to lignin; as well as possibly elucidating lignin binding mechanisms. These studies have led to the current paradigm that carbohydrate binding domains, with hydrophobic residues positioned towards the substrate surface, cause non-productive adsorption [13, 14]. Palonen et. al., using steam pretreated softwood, demonstrated that the primary cellulase “work horse” enzyme, Cel7A, and its catalytic domain (CD), exhibited higher affinity to softwood in comparison to Cel5A endoglucanase [13]. They also demonstrated that by removing the carbohydrate binding module (CBM) of Cel7A, a significant decrease in its binding efficiency was observed [13]. Similar results were reported by Rahikainen et. al., using quartz crystal microbalance analysis of enzyme dissipation with lignin isolated from steam explosion pretreated and non-pretreated spruce and wheat straw. They demonstrated an increase in the binding efficiency of Cel7A fully intact (both the catalytic domain and the CBM) in comparison to the CD of Cel7A alone [14]. This approach; however, does not permit the measurement of free enzymes interacting with lignin in a mixed protein cocktail, such as commercial cellulases. Others have suggested that irreversible adsorption can be caused by exposed hydrophobic core amino acids binding to lignin during heat-induced denaturation [15]. An alternative theory suggests lignin-induced deactivation is due to non-specific binding of small, lignin-derived phenylpropane units, which act as inhibitors, functionally blocking enzyme active sites [16, 17].

Aside from inhibition by low molecular weight lignins, enzyme-lignin interaction is dependent upon multiple intrinsic properties of the proteins and lignins. As protein properties vary significantly across and even within enzyme families, a simple direct relationship is not obvious. This relationship is compounded by source-dependent structural and chemical properties of lignin and changes caused by pretreatment chemistry and severity. An enzyme’s affinity for a specific substrate is dependent upon its physiochemical properties, such as molecular weight, surface charges, hydrophobicity, and the capacity for inter-molecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonding or pi-orbital effects. These factors affect interactions between other enzymes and biomass components; as well as lignin. All of these interactions occur in a competitive way, following the principle of the Vroman Effect; e.g., until an equilibrium driven by the enzymes’ affinity for the various substrates has been reached. Adsorption rates and mechanisms measured with individual enzymes may not be displayed in a mixed population of proteins, where competitive binding by multiple enzymes for the same substrate(s) may affect enzyme-substrate interactions [15, 18, 19].

Non-productive absorption of cellulases to lignin can lead to reduced cellulase activity, requiring higher enzyme loadings or longer hydrolysis times to reach economic conversion levels [14]. This condition also suggests that any enzyme recycle strategy would be severely limited if the required activities were bound to lignin and removed from the recycle stream with the solid residues [11]. This work explores how a mixed population of enzymes from commercial cellulase preparations interacts with lignin; as well as the interactions of lignin with purified enzymes.

Lignin-enzyme binding is affected by the hydrophobicity and surface charges on each component, which are affected in turn by temperature and pH [11]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that purified cellulases and other glycoside hydrolases bind to lignin and have concluded that reducing lignin content or protein modification to reduce its affinity to lignin should increase the effective conversion rate [11, 14, 20]. In order to understand the magnitude of these individual interactions, we have used specific enzyme assays and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis to track the partitioning of enzyme activities and protein bands between the lignin bound and unbound fractions of complex commercial cellulase systems as a whole.

We have recently reported that there is a hierarchy of lignin-binding affinity across enzymes involved in biomass hydrolysis correlated to hydrophobic patches on protein surfaces [15, 21]. It was further discovered that β-D-glucosidases and xylanases bind preferentially over cellulases and, moreover, remain active when bound [21]. It seems evolutionarily consistent that the enzymes that do not contain CBMs and display the highest lignin binding affinity also remain active when bound to lignin. Perhaps Nature selected a strategy for retaining these activities near their site of action, while simultaneously sequestering them away from cellulosic binding sites - thus blocking non-productive cellulase binding sites on lignin.

In this work, we have carried these studies further, probing differences in protein-lignin binding of different types of commercially available cellulase products. Until recently, commercial cellulases were generally produced by induction of selected cellulase hyper-producing strains of Hypocrea jecorina, (formerly Trichoderma reesei). These “native” systems were improved after discovering that certain additional activities could enhance the conversion rates of specific biomass feedstock types. For example, feedstocks could comprise different plants, pretreatments, or combinations of both [22, 23]. Essentially, enzyme producers realized that a “one-size-fits-all” cellulase did not effectively address the wide range of biomass type-pretreatment chemistry combinations. Initially, these augmented cellulases were produced by blending different secretomes containing the desired activities. More recently, some required activities have been genetically engineered into production strains. While cellulase producers consider these formulation details confidential, we wondered if these improvements, measured as enzyme classes, impacted the hierarchy of protein-lignin binding. To that end, we tested six different commercial formulations to see which activities preferentially bound to lignin. These formulations included three native secretomes (Spezyme CP, GC220 and Celluclast 1.5L), one augmented secretome, Novozymes Ctec2 and two engineered secretomes, Accellerase Duet and Prep X which due to proprietary agreements can not be officially identified.

Methods

Steam Explosion Pretreatment of Corn Stover

Corn stover was pretreated in an insulated and electrically pre-heated Hastelloy C-22 four-L steam explosion reactor at 180°C, 1% (w/w) H2SO4, for 3 min [24]. The reactor was loaded with 500 g of acid impregnated and pressed corn stover (~43% solids), sealed with the top ball valve, and steam applied to both the top and bottom of the reactor interior to quickly heat (~5 to 10 s) the biomass to reaction temperature. The timer is started when the reactor contents measured by two thermocouples inside the reactor reach reaction temperature. The bottom ball valve is quickly opened at the desired experimental residence time and the pretreated solids are blown into a nylon HotFill® bag inside a 200-L flash tank. The bag is removed from the flash tank, labeled, sealed, and stored at 4°C until ready for analysis. This allows collection of all steam and volatile components (furfural and acetic acid) in the slurry for more accurate component mass balance measurements.

Lignin Extraction Method

Lignin from the pretreated corn stover was extracted with aqueous dioxane utilizing a modified Bjorkman method whereby the milling, acetone extraction, and 0.1M HCl reflux at 90°C steps have been eliminated as the samples have already been milled and pretreated under acidic conditions [25]. Soluble carbohydrates and byproducts generated during pretreatment were removed by resuspending approximately 100 g wet weight of pretreated solid residues five times in 100 mL deionization (DI) water and filtering under vacuum using 90 mm Whatman glass fiber (GF/A). The washed solids were then suspended in 600 mL of a 9:1 (v/v) mixture of dioxane (1,4-dioxane, J.T. Baker) and DI water and extracted for 1 h at 120°C with intermittent stirring to keep the solid particles suspended. The dioxane-extracted solids were filtered with Whatman GF/A glass fiber filters and washed with 500 mL of 95% ethanol followed by a 500 mL wash with DI water.

Soluble solids in the dioxane:water extraction liquors were concentrated to 50 to 100 mL utilizing a rotary type evaporator, precipitated by adding cold DI water (4X the final extract volume), and centrifuged in a GSA rotor at 13,185 x g for 30 min. The precipitated solids were washed 3x with 150 mL DI water and freeze dried for characterization by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and gel permeation chromatography (GPC). The yield of lignin extracted with 9:1 dioxane ranged from roughly 15% to nearly 40% of the resident lignin content by weight.

Chemical Compositional Analysis

The compositions of the pretreated and dioxane-extracted samples were measured using a modified version of the NREL standard method (NREL/TP-510-42618). Because only relatively small amounts of sample were available for compositional analysis, the analyses were performed on 100 mg samples instead of the standard of 300 mg. Sugars and sugar degradation products, i.e., furfural and hydroxymethyl furfural, were measured using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) equipped with refractive index and photodiode array detectors (Agilent 1100, Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). A Rezex RFQ Fast Acids column (100 × 7.8 mm, 8 μm particle size, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) and Cation H+ guard column (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) operated at 85°C were used to separate sugar monomers, total oligomers, and degradation products present in the reaction solutions. The eluent was 0.01N H2SO4 at a flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1. Samples and standards were filtered through 0.45 μm nylon membrane syringe filters (Pall Corp., East Hills, NY) prior to injection (2.5 μL) onto the column. The HPLC was controlled and data was analyzed using Agilent ChemStation software (Rev.B.03.02).

13C CP/MAS Solid State NMR

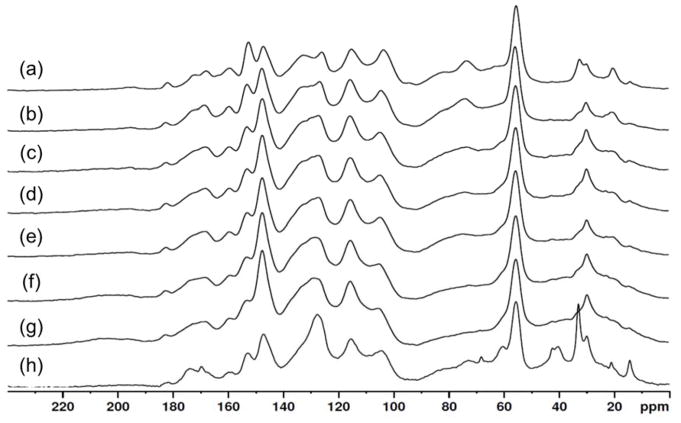

High-resolution 13C cross polarization/magic-angle spinning (CP/MAS) solid-state NMR measurement was performed with a Bruker Avance 200 MHz spectrometer operating at 50.13 MHz for 13C at room temperature. The spinning speed was 7000 Hz, contact pulse 2 ms, acquisition time 32.8 ms and delay between pulses 1 s. Lignin content was estimated on the basis of both normalized signal due to lignin aromatic structure (109–165 ppm) and normalized signal area due to the carbohydrate fraction (40–109 ppm, 165–240 ppm adjusted to allow for the peak area of the lignin methoxyl peak) (Figure 1), according to a previous study[26].

Figure 1.

13C CPMAS solid-state NMR spectra of the 90% dioxane extractives from dilute-acid pretreated corn stover in 1% H2SO4 after at different temperature and reaction time (DAP-lignin). (a) Corn stover ball milled lignin, (b) 150°C/5min, (C) 150°C/20min, (d) 150°C/30min, (e) 170°C/5min, (f) 170°C/20min, (g) 170°C/30min, (h) 180°C/3min.

Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) Analysis

The isolated lignin samples were acetylated with a mixture of pyridine/acetic anhydride (1:1, v/v) at 40°C for 24 h. The reaction was terminated by addition of methanol. The acetylation reagents were removed by a stream of nitrogen gas. The samples were further dried in a vacuum oven at 40°C overnight. A final drying was performed under vacuum (1 Torr) at room temperature for 1 h. The dried acetylated samples were dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (THF, Baker HPLC grade). The dissolved samples were filtered (0.45 μm nylon membrane syringe filters) before GPC analysis. The acetylated samples appeared to be completely soluble in THF.

GPC analysis was performed using an Agilent HPLC with three polystyrene-divinyl benzene GPC columns (Polymer Laboratories, 300 × 7.5 mm, 10 μm beads) having nominal pore diameters of 104, 103, and 50 Å respectively. The eluent was THF, the flow rate 1.0 mL/min, the sample concentration was ~2 mg/mL and an injection volume of 25 μL was used. The HPLC was attached to a diode array detector measuring absorbance at 260 nm (band width 40 nm). Polystyrene calibration standards were used with molecular weights ranging from 580 Da. to 2.95 million Da. Toluene was used as the monomer calibration standard.

Enzyme Adsorption Assays

Partitioning of commercial cellulase enzyme subpopulations was studied by monitoring losses in activities between the starting whole cellulase and the unbound fraction after exposure and binding to insoluble lignin. Partitioning of individual proteins was followed at the macro level through observation of changes in SDS-PAGE gel bands before and after binding to lignin. Briefly, a total of 0.3 μg of desalted protein was incubated with 6 mg of lignin, corresponding to a process loading of 25 mg protein/g cellulose for biomass containing 30% lignin and 60% cellulose. The protein/lignin combination (1.0 mL total volume) was incubated at 45°C for 60 min in 25 mM sodium citrate buffer at pH 4.8 unless otherwise stated. Previous studies demonstrated the enzymes reach a state of equilibrium within 60 min [15]. After the incubation, the sample was centrifuged at 20,000 × g and the supernatant containing the unbound protein was collected. The lignin pellet was washed an additional four times with buffer.

Desalting Enzyme Preparations

In order to remove potential binding and activity interference from low molecular weight formulating compounds and peptide fragments, the commercial enzyme preparations were diluted 1:10 in 25 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.8), passed through a 0.2 μm PES syringe filter, and desalted in 10 mL aliquots over two serial HiPrep 26/10 desalting columns (GE Life Sciences, Piscataway NJ) equilibrated with the same buffer. A280 was followed and protein-containing fractions were pooled. Protein concentration in the pooled fractions was determined using the BCA protein assay (Pierce Rockford, IL). Enzyme samples were desalted up to two days before use, with fresh material being generated for each experiment, as desalted commercial enzymes tended to form a precipitate within a few days.

SDS-PAGE Gel Assays

Pre-cast 4 to 12% SDS-PAGE gels (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) were used to visualize proteins bound and unbound to extracted corn stover lignin. The desalted starting enzyme, supernatant containing unbound proteins, and the lignin pellet containing protein bound to insoluble lignin were diluted with 4X LDS sample buffer (3:1 sample to buffer), boiled for 10 min, and loaded onto the gels. Gels were run at 200V constant for 50 min in a discontinuous vertical gel box system running MOPS-SDS buffer.

Para-nitrophenyl Assays

A variety of para-nitrophenyl (pNP) substrates (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were used to determine the enzymatic activities of the unbound fraction of commercial cellulases after exposure to lignin. Substrates used were pNP-β-D-lactopyranoside, pNP-β-D-cellobioside, pNP-β-D-glucopyranoside, and pNP-β-D-xylopyranoside. Each assay (2 mM working concentration of pNP substrate) was prepared using a 10 mM stock solution in 25 mM sodium citrate buffer at pH 4.8.

Desalted commercial enzyme preparations were used at a concentration of 50 μg/mL, 5 μg/mL, and 0.5 μg/mL in a 2.0 mM pNP solution. All the pNP substrates were incubated at 45°C for 30 min. After incubation, the reaction was stopped and color developed by the addition of 2-fold volume of 1.0 M sodium carbonate. Absorbance at 405 nm was measured in a spectrophotometer.

Results and Discussion

Lignin Compositional Analysis

The compositions of each dioxane extract were determined by the wet chemistry method [27]. As pretreatment severity increased, i.e., as temperature, acid concentration, and reaction time was increased, the lignin contents of the extracts increased and the carbohydrate contents decreased as demonstrated in Table 1. The most severely pretreated sample (12) had the highest lignin content of 95.3 wt% and the lowest carbohydrate content of 1.5 wt%.

Table 1.

Compositions of Dioxane Extracts From Steam Gun Pretreated Corn Stover Samples.

| Wet Chemistry | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition (wt % of dry biomass) | Arabinan1 | Galactan2 | Glucan3 | Xylan4 | Total Carbohydrate | Lignin | Total |

| 1%H2SO4/150°C/ 5 min | 1.41 | 0.18 | 1.01 | 3.83 | 6.43 | 85.0 | 91.4 |

| 1%H2SO4/150°C/ 30 min | 1.07 | 0.13 | 0.73 | 1.65 | 3.58 | 88.8 | 92.3 |

| 1%H2SO4/150°C/ 60 min | 0.77 | 0.10 | 0.53 | 1.06 | 2.46 | 91.3 | 93.8 |

| 1%H2SO4/170°C/ 5 min | 1.11 | 0.10 | 0.71 | 1.36 | 3.28 | 88.5 | 91.7 |

| 1%H2SO4/170°C/ 60 min | 0.51 | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0.44 | 1.45 | 95.3 | 96.7 |

| 1%H2SO4/180°C/ 3 min | 0.47 | ND | 1.77 | 1.10 | 3.34 | 88.8 | 92.1 |

Values calculated as polymer, though most of the arabinose is found as xylan side-chains.

Values calculated as polymer, though most galactose is as minor component of hemicellulose.

Glucan is calculated from glucose and includes glucose from cellulose, xyloglucan, β-glucan, and starch.

Xylan is calculated as polymer and concludes xylose from xylan and xyloglucan.

Solid-State NMR Analysis

13C CPMAS NMR spectra of the dioxane extractives from corn stover pretreated with 1% H2SO4 are shown in Figure 1. Almost all signals are assigned according to references [28–30]. Each spectrum was normalized by peak height of methoxyl group at 56 ppm

There are two regions to focus on in the NMR spectra, the first is between 62–109 ppm, this region is the carbohydrate fingerprint region and the second region between 109 to 165 is the finger print region for the aromatic carbons in lignin. When comparing the spectra in figure 1, there is a steady decrease in signal within the carbohydrate finger print region as the severity of the pretreatment increased, signaling that with higher pretreatment, the extracted lignin contains very little carbohydrates. This conclusion is further supported with the compositional analysis given previously in Table 1. Because of the low carbohydrate content of this lignin, it is an ideal candidate to study how enzymes interact with lignin.

Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) Analysis

GPC chromatograms of corn stover (CS) ball milled lignin and DAP-lignin extracted from corn stover prepared in 1% H2SO4 at 180°C were shown in Figure 2. DAP-lignin has large monomeric compounds (200 to 400 Da) and higher Mw portion comparing with CS ball milled lignin. The estimated weight average molecular weight (Mw) for the DAP-lignin is 10,000 Da and 6,400 Da for the CS ball milled lignin. Polydispersity of the DAP-lignin is 11.2, which is much higher than that found for the CS ball milled lignin (3.8).

Figure 2.

Gel permeation chromatograms of the dioxane-H2O extracted lignin from dilute-acid pretreated corn stover (1% H2SO4, 180°C, 3 min) and corn stover ball milled lignin.

SDS-PAGE Analysis of Protein Partitioning

Six commercial cellulase formulations were utilized for the lignin binding study: two engineered (Dupont Accellerase Duet, Prep X), one augmented (Ctec2), and three native (Spezyme, GC220 and Celluclast 1.5). Figure 3 depicts SDS-PAGE gels of three fractions of each cellulase: Lane 1- desalted cellulase, Lane 2- unbound proteins, and 3) proteins bound to lignin. Adjacent to each gel is the corresponding intensity plot of the gel bands generated utilizing ImageJ gel analysis (developed at the National Institutes of Heath (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/docs/menues/analyze.html#gels). Densitometry was used in conjunction with ImageJ to determine the percent difference in protein concentration for control and unbound fractions [31, 32]. The three scans are labeled accordingly; control, unbound fraction, and bound fraction. This type of gel analysis aids in the quick visualization of missing bands from the unbound fraction and the bound fraction in comparison to the control and other samples.

Figure 3.

SDS-PAGE and associated lane density scans of six commercial cellulases. For each panel, Lane 1 = SeeBlue+2 MW std, Lane 2 = whole cellulase, Lane 3 = supernatant after binding to lignin, Lane 4 = lignin pellet and associated bound protein.

The LDS sample buffer in combination with boiling proved effective at separating the bound proteins from the lignin, as evidenced by clear protein bands in the resolving range of the gel and heavy diffuse low molecular weight compounds running with the dye-front. This low molecular weight population was also present in lignin-only lanes and presumably corresponds to the lignin (data not shown). Across the six cellulase formulations, there are clear differences in the protein banding patterns between whole, unbound, and bound fractions. These can be arbitrarily separated into high, mid, and low molecular weight subpopulations, highlighted by the rose, green, and purple shading in Figure 3.

The native cellulase preparations clearly bind less protein at the high and low molecular weight range compared to the engineered and augmented cellulase formulations. This result is not unexpected, as these formulations are known to be generally high in cellulase (intermediate MW) and low in β-D-glucosidase (high MW) and xylanase (low MW) activities [15, 33]. In general, the binding affinity of proteins in the native cellulase preparations is weaker compared to that shown by augmented and engineered cellulases formulations. The protein affinity within the augmented and engineered formulations are more numerous than the native preparations and demonstrate clear binding of specific bands in both the high (Ctec2, Prep X, Accellerase Duet) and low (Accellerase Duet) molecular weight ranges. These bands are generally not present in the native systems, which suggest that they have been added through secretome blending or genetic modification.

Quantification of Protein Loss

Although pNP activities are informative, they do not give direct insight into the amount of protein lost to lignin. The pixel density of SDS-PAGE protein bands from the whole broth and the unbound fraction was utilized to calculate the difference between the two bands, providing a direct measurement of the amount of protein lost to lignin absorption via densitometry using ImageJ (Figure 4)[31, 32]. Due to the complex nature of these commercial formulations and the difficulty of identifying the specific protein comprising each band, we simplified the interpretation by looking at the total area as defined by the high molecular weight (HMW, red shaded area), medium molecular weight (MMW, green shaded region) and the low molecular weight (LMW, purple shaded region) in Figure 3. Figure 4 shows the percent loss in total protein within each molecular weight region for all six commercial formulations, with Table 1 giving the specific percent of protein lost for each commercial product. On average, the commercial formulations showed a decrease of 67.4% +/− 13.3% in the HMW proteins, a decrease of 21.8% +/− 12.6% in the MMW proteins, and a decrease of 32.7% +/−19.1% in the LMW proteins.

Figure 4.

Percent loss in total protein within high molecular weight region (red column), medium molecular weight (green column) and low molecular weight region (purple) for all six commercial formulations.

pNP Assays for Activity Partitioning

Activities of the control (desalted cellulase) and unbound fraction were assayed with multiple pNP-substrates. Activities that were significant on four of the seven substrates included: pNP-β-D-lactopyranoside (ρNPL), pNP-β-D-xylopyranoside (pNPX), pNP-β-D-cellobioside (pNPC), and pNP-β-D-glucopyranoside (pNPG). These substrates were selected for use in more detailed assays to track the loss of enzyme activity and change in gel bands after binding of the cellulases to lignin. Binding assays were carried out at 25 mg protein per g cellulose equivalents for each substrate and protein type. However, due to different intrinsic activity rates as well as differing amounts of various enzymes in the broths, dilutions were made of the some whole enzyme preps for some of the pNP assays as previously described. This ensured the absorbance measured was within the range of the activities and not saturated at the detection limit of the spectrophotometer. For pNPC assays, Ctec2 and Prep X were diluted 100-fold in buffer while Accellerase Duet and GC220 were diluted 10-fold. For pNPG assays, Ctec2, Prep X, and Accellerase Duet were diluted 100-fold while all three native preps were diluted 10-fold.

Differences between the activity of the whole broth and the unbound fraction were calculated by normalizing both fractions to the whole broth (Table 3). Although we are measuring the amount of activity remaining in the supernatant after binding to lignin, it is reasonable to assume that the lost activity is bound to lignin. Rather than refer to results in terms of activity losses in the unbound fraction after binding to lignin, we will consider them as the fraction of activity bound to lignin, giving us a direct means of comparing binding affinity between different activities and proteins.

Table 3.

Loss of Activity Due to Enzyme Binding to Lignin

| Cellulase | pNPL | pNPX | pNPC | pNPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctec2 | 17.6% | 84.5% | 97.9% | 64.5% |

| Prep X | 25.7% | 32.2% | 98.8% | 75.2% |

| Accellerase Duet | 36.1% | 100% | 79.4% | 27.5% |

| GC220 | 18.0% | 100% | 53.6% | 49.9% |

| Spezyme | 25.2% | 100% | 34.2% | 35.7% |

| Celluclast 1.5 | 28.6% | 100% | 33.8% | 30.7% |

pNP-Lactopyranoside

The pNPL activity assay was used as an indicator of primarily cellobiohydrolase (CBH) activity. Though other cellulases likely have cross-reactivity with pNPL, CBHs have been demonstrated to have a particular affinity for this substrate. The pNP-lactopyranosidase activity of whole and unbound cellulase fractions for each cellulase is shown in Figure 5. The average total release of pNP substrate across all six whole cellulases was 123.37 +/− 33.86 uM. Four of the six cellulases are close in activity on pNPL, with Ctec2 and Accellerase Duet having a statistically lower activity than the other four. This variation is likely due to differences in the specific cellulase/cellobiohydrolase activity of the different products. Different compositions of specific proteins may also skew this data, as different proteins can react differently to protein detection reagents. This is especially true for cellobiohydrolase I [34].

Figure 5.

Shown is the loss of four p-nitrophenyl substrate activities from commercial preparations in the presence of lignin. Blue = activity of whole cellulase broth. Red = activity of unbound fraction after binding to lignin. For the ρ-nitrophenyl-β-D-cellobiosidase assays, Ctec2 and Prep X needed to be diluted 100-fold and Accellerase Duet and GC220, Spezyme and Celluclast 1.5L needed to be diluted 10-fold.

After incubating the whole cellulases with lignin, all six cellulases demonstrated similar levels of pNPL activity binding to lignin. Again, GC220 exhibited the highest overall activity, though the fractional activity losses are nearly identical for each of the six cellulases. The overall average activity of the unbound fractions was 107.38+/− 29.496 μM. This is an average 13.96 % binding of pNPL activity between the control and the unbound fraction.

pNP-Xylopyranoside

pNP-D-xylopyranoside served as an indicator of xylanase and β-D-xylosidase activity. Figure 5 shows the pNP-D-xylopyranoside activity of the six cellulase preparations with a significant difference in the overall activity between the commercial formulation controls. There was a wide range of pNPX activity found across the six samples, indicating a wide variation in xylanase activity (data not shown). This result is not unexpected, especially as older, native-type cellulases often required the addition of a commercial xylanase to make a complete biomass-hydrolyzing preparation. This assumption is likely the case for the Accellerase Duet cellulase, for which it is well known that the addition of xylanase, β-D-xylosidase, and accessory hemicellulase enzymes enhances the conversion of biomass by cellulase mixtures [35]. Additional xylanase or β-D-xylosidase activity is likely the reason for the significant increase in the pNPX activity in Prep X, as this product has been engineered for corn stover biomass-to-fuels.

What is also interesting is that five of the six cellulase preparations exhibit extensive binding of pNPX activity to lignin. It appears that, in general, pNPX active proteins have a very high affinity towards lignin or possibility to the associated lignin carbohydrate complexes (LCCs). An exception here is Prep X, which retains 68% of its pNPX activity in the unbound fraction. Whereas Ctec2 exhibited higher pNPX activity binding to lignin (>80%), it was the only other formulation to retain a significant fraction of pNPX activity in the unbound fraction. It stands to reason that this is due to the particular pNPX active enzyme(s) engineered into these cellulases.

Para-nitrophenyl-cellobioside

The pNPC is used to measure cellulase activity of β-D-glucosidases and endo-cellulases over cellobiohydrolases. Figure 5 also shows the pNP-cellobioside activity of the six preparations. Ctec2 and Prep X cellulases showed 100% binding of pNPC activity to lignin and Accellerase Duet showed a 80% loss in pNPC activity. In contrast, the three native cellulases (GC220, Spezyme, Celluclast 1.5) showed low binding affinities (<50% pNPC activity bound) of pNPC activity to lignin and their overall starting activity was much lower than that Accellerase Duet Ctec2, or Prep X. While this appears confusing at first, the simple explanation may reside in the high β-D-glucosidase activity in Accellerase Duet, Ctec2, and Prep X (see below). Many β-D-glucosidases have high activity on higher oligomers, such as pNPC (a cellotriose analogue). Others, more specifically referred to as cellobiases, are most active on cellobiose (i.e., pNPG as an analogue) and have decreasing activity as the degree of polymerization of the cello-oligomer increases.

pNP-glucopyranoside

pNP-glucopyranoside was utilized to assay for β-D-glucosidase activity, though as with other pNP substrates, there is always cross reactivity with other enzymes. The pNPG activity of the six cellulases shown in Figure 5 is similar in pattern to that of pNPC, with Accellerase Duet, Ctec2, and Prep X requiring 10-fold dilution of the starting enzyme before binding and assaying. It has long been know that β-D-glucosidase activity on the native Trichoderma system is expressed at low levels and that augmentation with exogenous β-D-glucosidase activity is required for effective biomass hydrolysis [36–38]. In our previous work, we clearly demonstrated that β-D-glucosidase from Aspergillus niger (often used to augment T. reesei cellulases) has a very high binding affinity for lignin [15]. It is therefore not surprising that in engineered and augmented cellulases, the β-D-glucosidase activity is highly partitioned to the solid lignin phase. It is also apparent that the native Trichoderma β-D-glucosidase(s) have lower affinity for lignin than the presumably heterologous activity in the engineered cellulases, as only 50 to70% of the pNPG activity in the native systems bound, compared to 100% in the engineered cellulases.

Figure 5 shows all four p-nitrophenyl substrate activities for all six commercial preparations. This helps visualize the actual variability of cellulase activity in the presence of lignin. There is no a significant amount of loss of activity on pNPL; however, there is a significant difference between Prep X on pNPX and the native commercial preparations on pNPC. The variation of activity loss on pNPG can be seen between all six commercial formulations Table 3 summarizes the loss of the four pNP activities attributed to binding affinity of protein to lignin. It is clear from the table that losses of pNPL activity are low regardless of the cellulase type. As pNPL is a good indicator of cellobiohydrolase activity, this low binding suggests that these exocellulases have generally poor lignin affinity. In contrast, the level of bound xylanase activity across the six cellulase preparations is very high and consistent with one major exception. The Prep X cellulase formulation demonstrates no binding of xylanase activity to lignin, which suggests that the major pNPX activity in Prep X is a non-native protein with markedly different binding affinity for lignin. This conclusion is important for future engineering efforts, as it clearly indicates that heterologous enzymes can be chosen not only for their enhanced activity, but also for physical properties such as their affinity for lignin.

The remaining measured cellulase activities, pNPC and pNPG, display some interesting binding patterns. The pNPC activity is generally considered an indicator of endocellulase activity, although certain aryl-β-D-glycosidases are known to have pNPC activity as well. There is generally low (~20%) binding of pNPC activity in the natural strains; however, the augmented and engineered cellulases lose 100% of the pNPC activity to lignin binding, suggesting that the endocellulase activity in these preps is not native, i.e. it exhibits a very different binding behavior than the pNPC activity in native strains. Alternatively, it may be that the pNPC activity is due to a heterologous β-D-glucosidase with high activity on pNPC, either heterologously expressed in the engineered strains or produced by a different species and added to the broth for the augmented strain. This conclusion is also suggested by the pNPG activity losses, which while demonstrating somewhat higher overall binding for the native cellulases (~60% bound) show similar binding patterns with the exception of the augmented strain.

Discussion

Commercial cellulase preparations fall into several broad types, the native secretomes, multiple-strain augmented secretomes, and engineered-strain secretomes containing one or more non-native activities introduced genetically to enhance a particular activity. To determine which class of enzymes adsorb to the surface of lignin; as well as if this binding affects the secretome activity, binding/activity experiments were designed using six commercial cellulase preparations and lignin extracted from pretreated corn stover. The different classes of enzymes were tracked by mixing the commercial enzyme preparations with lignin and analyzing proteins partitioned into the bound (lignin pellet) and unbound (supernatant) fractions. A range of p-nitrophenol substrates, including pNPL, pNPC, pNPX, and pNPG were used to estimate the type of activity remaining in each fraction. The pNP assays was also used in conjunction with the quantifiable gel technique that provides a fast and valuable insight into the inner workings of these commercial cellulases. Combining these two techniques allows the ability to track activity and correlate the activities to individual proteins from different commercially available enzyme preparations for their affinity toward lignin

Individual proteins within these commercially available products bind differently to lignin. Controls of protein- and lignin-only samples indicate the proteins can be found in either the bound or unbound fractions (Figure 3). The high molecular weight proteins (rose highlights, Figure 3) and low molecular weight proteins in Ctec2, Prep X, Accellerase Duet (purple highlights, Figure 3), have a high affinity for lignin, as they are absent in the unbound fractions and prominent in the bound fractions. Intermediate molecular weight proteins (green highlight, Figure 3) were largely unbound. Note that the large band located at the bottom of the bound fraction is the lignin pellet. Figure 5 shows the activity profile of the commercial enzyme products (red bars) and unbound fraction (blue bars). We conclude that the combination of activity loss and bound molecular weights can be used for identifying the proteins binding to lignin. Major bound activities include pNPC and pNPG, presumably attributable to β-D-glucosidase enzymes present in the high molecular weight (>80 kDa) bands. The pNPX activity was also mostly bound to lignin and is presumably correlated with the bound low molecular weight (<30 kDa) proteins, considering that xylanases are typically low molecular weight. Cellulase activity, indicated by the pNPL activity, remained mainly unbound and is presumed to be associated with the intermediate molecular weight (30 to 80 kDa) bands. Table 3 shows the overall percent of pNP activity bound to lignin.

Throughout this experiment, the enzymes adsorbed to lignin are physically removed from the unbound fraction by the removal of the lignin. The question becomes, what happens to the overall hydrolysis of biomass with these proteins having a high affinity toward lignin? In our previous work, we looked at the adsorption of these protein to lignin and their inhibition toward the overall conversion of Avicel [21].

This work demonstrated the unbound CTec2 enzyme fraction had reduced conversion of Avicel vs. complete Ctec2, with a 26% difference in conversion between the two [21]. The prolonged production of cellobiose using the lignin-depleted commercial cellulase product suggests that end-product inhibition of cellobiohydrolase I may be the primary cause of the observed productivity loss. Interestingly, Avicel hydrolysis with CTec2 in the presence of lignin (Figure xx blue) results in a only a 10% decrease in glucan conversion and decreased cellobiose accumulation, suggesting the β-D-glucosidase in CTec2, which seems to be especially susceptible to lignin binding, remains active in the presence of lignin [21].

Conclusion

Without detailed identification about the individual proteins found in each cellulase preparation, it is impossible to know with certainty which specific enzymes are responsible for the pNP activities or are binding/not-binding to lignin. Nonetheless, a key finding of this work is the observation that exocellulase (and possibly endocellulase) activity in commercial “cellulases” is generally unaffected by binding to lignin. This conclusion contrasts to results from other groups that have shown binding of cellobiohydrolase I to lignin. Two scenarios may explain this. First, other studies have used purified enzymes to study the binding affinity in a “clean” system. We assert that the interactions of single enzymes on a substrate will be different than the interactions of the same enzyme and substrate in the presence of other proteins with the capacity to bind to the same substrate. At that point, it becomes an affinity-partitioning scenario and high affinity proteins (such as β-D-glucosidase and xylanase) can readily displace low-affinity enzymes such as exocellulases. Second, it is likely that the use of different or cellulose-contaminated lignin could cause a dramatic change in the binding of proteins. This is especially true for cellobiohydrolases, which contain family 1 CBMs known to have a very high affinity for cellulose and one could speculate that a small polysaccharide content in a lignin preparation could bind a relatively high concentration of cellobiohydrolase.

In contrast, activities on pNPX and pNPG appear to vary widely in their affinity for lignin, likely as a result of being from different species in the different commercial cellulases. This is a good indication that complex cellulase activity can be fine-tuned for a specific feedstock and/or pretreatment schemes and that the individual enzymes are likely to be susceptible to modification of their binding properties, either by selecting different source genes or by engineering the proteins to alter binding-contributing amino acids. This work also suggest that tailoring/engineering cellulase systems to specific substrates while effective may not be the most cost effect approach. Taking into consideation, β-D-glucosidase it is effectively bound to the substrate yet has be shown to be catalytically active in the bond state. Another point as Nakagame demonstrated, lignin from different plant origins coupled with varied pretreatment chemistries and severities may result in a variable adsorption surface chemistry and enzyme accessibility[9, 10]. Therefore it is important to choose a commercial enzyme preparations that is minimally affected by the presences of the lignin. Therefore, his technique developed and described in this paper allows for a quick determination of this interaction leading to using the optimal commercially available enzyme preparation.

Table 2.

Loss of Protein Due to The Absorption to Lignin for The Three Molecular Weight Regions, High Molecular Weight, Medium Molecular Weight and Low Molecular Weight

| Cellulase | HMW | MMW | LMW |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ctec2 | 81.6% | 23.7% | 31.0% |

| Prep X | 72.5% | 16.6% | 36.4% |

| Accellerase Duet | 76.5% | 30.3% | 11.5% |

| GC220 | 66.0% | 35.8% | 45.3% |

| Spezyme | 43.7% | 25.8% | 60.4% |

| Celluclast 1.5L | 64.2% | 22.5% | 11.9% |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC36–08GO28308 with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory and by the Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Bioenergy Technologies Office (BETO).

Footnotes

Disclaimer:

Commercial equipment, instruments or materials are identified only in order to adequately specify certain procedures. In no case does such identification imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standard and Technology nor does it imply that the products identified are necessarily the best available for the purpose.

References

- 1.Vinzant TB, et al. Simultaneous saccharification and fermentation of pretreated hardwoods - Effect of native lignin content. Applied biochemistry and biotechnology. 1997;62(1):99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar R, Wyman CE. Access of cellulase to cellulose and lignin for poplar solids produced by leading pretreatment technologies. Biotechnology progress. 2009;25(3):807–19. doi: 10.1002/btpr.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mooney CA, et al. The effect of initial pore volume and lignin content on the enzymatic hydrolysis of softwoods. Bioresource technology. 1998;64(2):113–119. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vinzant TB, et al. Ssf Comparison of Selected Woods from Southern Sawmills. Applied biochemistry and biotechnology. 1994;45–6:611–626. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donohoe BS, et al. Visualizing Lignin Coalescence and Migration Through Maize Cell Walls Following Thermochemical Pretreatment. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2008;101(5):913–925. doi: 10.1002/bit.21959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun Q, et al. Effect of lignin content on changes occurring in poplar cellulose ultrastructure during dilute acid pretreatment. Biotechnology for Biofuels. 2014;7(1):150. doi: 10.1186/s13068-014-0150-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu L, et al. Structural features affecting biomass enzymatic digestibility. Bioresource Technology. 2008;99(9):3817–3828. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakagame S, Chandra RP, Saddler JN. The Effect of Isolated Lignins, Obtained From a Range of Pretreated Lignocellulosic Substrates, on Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2010;105(5):871–879. doi: 10.1002/bit.22626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakagame S, et al. Enhancing the enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass by increasing the carboxylic acid content of the associated lignin. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 2011;108(3):538–48. doi: 10.1002/bit.22981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakagame S, et al. The isolation, characterization and effect of lignin isolated from steam pretreated Douglas-fir on the enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose. Bioresource technology. 2011;102(6):4507–17. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.12.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lou H, et al. pH-Induced lignin surface modification to reduce nonspecific cellulase binding and enhance enzymatic saccharification of lignocelluloses. ChemSusChem. 2013;6(5):919–27. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201200859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horbett TA, Brash JL. Proteins at Interfaces - Current Issues and Future-Prospects. Acs Symposium Series. 1987;343:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palonen H, et al. Adsorption of Trichoderma reesei CBH I and EG II and their catalytic domains on steam pretreated softwood and isolated lignin. Journal of Biotechnology. 2004;107(1):65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahikainen J, et al. Inhibitory effect of lignin during cellulose bioconversion: the effect of lignin chemistry on non-productive enzyme adsorption. Bioresour Technol. 2013;133:270– 278. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sammond DW, et al. Predicting Enzyme Adsorption to Lignin Films by Calculating Enzyme Surface Hydrophobicity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2014;289(30):20960–20969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.573642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ximenes E, et al. Inhibition of cellulases by phenols. Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 2010;46(3–4):170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan X. Role of functional groups in lignin inhibition of enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose to glucose. Journal of Biobased Materials and Bioenergy. 2008;2(1):25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfeiffer KA, et al. Evaluating endoglucanase Cel7B-lignin interaction mechanisms and kinetics using quartz crystal microgravimetry. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2015 doi: 10.1002/bit.25657. p. n/a-n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahikainen JL, et al. Inhibitory effect of lignin during cellulose bioconversion: The effect of lignin chemistry on non-productive enzyme adsorption. Bioresource Technology. 2013;133:270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turon X, Rojas OJ, Deinhammer RS. Enzymatic kinetics of cellulose hydrolysis: a QCM-D study. Langmuir : the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids. 2008;24(8):3880–7. doi: 10.1021/la7032753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yarbrough JM, et al. New perspective on glycoside hydrolase binding to lignin from pretreated corn stover. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2015;8:214. doi: 10.1186/s13068-015-0397-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selig MJ, et al. Heterologous expression of Aspergillus niger beta-D-Xylosidase (XlnD): Characterization on lignocellulosic substrates. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 2008;146(1–3):57–68. doi: 10.1007/s12010-007-8069-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selig MJ, et al. Synergistic enhancement of cellobiohydrolase performance on pretreated corn stover by addition of xylanase and esterase activities. Bioresource technology. 2008;99(11):4997–5005. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X, et al. The impacts of deacetylation prior to dilute acid pretreatment on the bioethanol process. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2012;5(8) doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bjokman A. Studies on finely divided wood. Part 1. Extraction of lignin with neutral solvent. Svensk Papperstidning. 1956;59:477–485. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis MF, Schroeder HA, Maciel GE. Solid-State 13CNuclear Magnetic Resonance Studies of Wood Decay. II. White Rot Decay of Paper Birch. Holzforschung-International Journal of the Biology, Chemistry, Physics and Technology of Wood. 1994;48(3):186–192. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sluiter A, et al. Determination of structural carbohydrates and lignin in biomass. Laboratory analytical procedure. 2008:1617. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liitiä T, Maunu S, Hortling B. Solid-state NMR studies of residual lignin and its association with carbohydrates. Journal of pulp and paper science. 2000;26(9):323–330. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin SY, Dence CW. Methods in lignin chemistry. Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wikberg H, Maunu SL. Characterisation of thermally modified hard-and softwoods by 13 C CPMAS NMR. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2004;58(4):461–466. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boissonneault V, et al. MicroRNA-298 and microRNA-328 regulate expression of mouse β-amyloid precursor protein-converting enzyme 1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(4):1971–1981. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807530200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walsh JG, et al. Executioner caspase-3 and caspase-7 are functionally distinct proteases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105(35):12815–12819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707715105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vinzant TB, et al. Fingerprinting Trichoderma reesei hydrolases in a commercial cellulase preparation. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2001;91–93:99–107. doi: 10.1385/abab:91-93:1-9:99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adney W, et al. Assessing the Protein Concentration in Commercial Enzyme Preparations. In: Himmel ME, editor. Biomass Conversion. Humana Press; 2012. pp. 169–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Selig MJ, et al. Synergistic enhancement of cellobiohydrolase performance on pretreated corn stover by addition of xylanase and esterase activities. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99(11):4997–5005. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chir JL, et al. Hydrolysis of cellulose in synergistic mixtures of beta-glucosidase and endo/exocellulase Cel9A from Thermobifida fusca. Biotechnol Lett. 2011;33(4):777–82. doi: 10.1007/s10529-010-0500-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kadam SK, Demain AL. Addition of cloned beta-glucosidase enhances the degradation of crystalline cellulose by the Clostridium thermocellum cellulose complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;161(2):706–11. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92657-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seidle HF, et al. Physical and kinetic properties of the family 3 beta-glucosidase from Aspergillus niger which is important for cellulose breakdown. Protein J. 2004;23(1):11–23. doi: 10.1023/b:jopc.0000016254.58189.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]