Abstract

Objective

Reduced physical function and health-related quality of life are common in Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA), and further studies are needed that examine novel determinates of reduced physical function in RA. This study examines whether frailty, a state of increased vulnerability to stressors, is associated with differences in self-reported physical function among adults with RA.

Methods

Adults from a longitudinal RA cohort (n=124) participated in the study. Using an established definition of frailty, individuals with 3 or more of the following physical deficits were classified as frail: 1) body mass index ≤ 18.5, 2) low grip strength (adjusted for sex and BMI, measured by handheld dynamometer), 3) severe fatigue (measured by the Multidimensional Assessment of Fatigue), 4) slow 4-meter walking speed (adjusted for sex and height), 5) low physical activity (measured by the International Physical Activity Questionnaire). Individuals with 1 or 2 deficits were classified as “pre-frail”, and those with no deficits as “robust.” Self-reported physical function was assessed by the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) and the Valued Life Activities Difficulty scale. Regression analyses modeled associations of frailty category with HAQ and VLA Difficulty scores with and without controlling for age, sex, disease duration, C-reactive protein, use of oral steroids, and pain.

Results

Among adults with RA, being frail compared to being robust was associated with a 0.44 worse VLA score (p<0.01) when the effects of covariates are held constant.

Conclusions

Being frail, compared to being robust, is associated with clinically meaningful differences in self-reported physical function among adults with RA.

Keywords: Frailty, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Physical Disability, Patient-reported outcomes

Introduction

Broadening understanding of the determinants of reduced physical function in Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is necessary because, even as the therapeutic armamentarium for RA continues to grow, individuals with RA continue to commonly experience physical disability and reduced health-related quality of life [1,2]. One potential determinate of reduced physical function in RA is frailty. Frailty is often defined as, “… a syndrome of decreased reserve and resistance to stressors … causing vulnerability to adverse outcomes,” including impaired physical function and mortality [3]. Fried et al. operationalized a frailty definition characterized by sarcopenia, weakness, exhaustion, slowness, and low activity [3]. This definition of frailty is associated with reduced physical function, physical disability, and death in various, non-rheumatologic populations, such as the elderly and individuals with congestive heart failure and chronic kidney disease [4–6].

RA predisposes individuals to many of the factors that comprise the Fried definition of frailty, including sarcopenia, fatigue, and low activity [7–11]. However, the prevalence of frailty among individuals with RA has not been examined. Moreover, relationships between frailty and reduced physical function in RA are unknown. The present study aims to address this gap in the literature by testing the hypothesis that the Fried frailty definition is associated with differences in self-reported physical function among adults with RA.

Methods

Subjects

The sample for the present study was drawn from a cohort developed at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) to study relationships between body composition and physical function in Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA). Details of this cohort are reported by Katz et al. [12]. Briefly, participants for this cohort were drawn primarily from the UCSF RA Panel study. At the end of the telephone interviews in the study years 2007–2009, RA Panel participants who lived in the greater San Francisco Bay area and were willing to travel to UCSF were recruited for in-person assessments at the UCSF Clinical and Translational Science Institute’s Clinical Research Center. RA diagnoses using the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria were verified by medical record review [13]. Exclusion criteria were non–English speaking, age less than 18 years, current daily oral prednisone dose greater than 50 mg, current pregnancy, uncorrected vision problems that interfered with reading, and joint replacement within 1 year.

Of 242 eligible individuals, 97 (40.1%) declined participation, primarily because of transportation (n=36) and scheduling difficulties (n=38); 145 individuals completed the study visits. Four participants were excluded from the analysis because they did not complete the body composition assessment. Of the remaining 141 participants, 85 (60.3%) were women and 56 (39.7%) were men. The final sample for the present study was comprised of those participants with complete grip strength data (n=124). The study was approved by the UCSF IRB, Committee on Human Research, approval #11-05702.

Frailty Components

Frailty was assessed based on the method developed by Fried et al. [3]. Individuals with 3 or more of the following physical deficits were classified [13]as frail: 1) low body mass index, 2) low grip strength (adjusted for sex and BMI), 3) severe fatigue, 4) slow 4-meter walking speed (adjusted for sex and height), 5) low physical activity. Individuals with 1 or 2 deficits were classified as “pre-frail”, and those with no deficits as “robust.” Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2). BMI ≤ 18.5 was classified as low. Grip strength of the participant’s dominant hand was measured using a hand-held dynamometer [14]. In addition, lower extremity muscle strength was assessed using a Biodex® unit to measure peak isokinetic torque of knee extension as has been previously described [15,16]. For the primary analysis, grip strength cut points (adjusted for BMI and sex) from Fried et al. [17,3] were used to define low grip strength. For men, low grip strength (kg) was defined as: ≤29 for BMI <24, ≤30 for BMI 24.1-28, ≤32 for BMI>28. For women, low grip strength was defined as: ≤17 for BMI <23, ≤17.3 for BMI 23.1-26, ≤18 for BMI 26.1-29, ≤21 BMI>29. The fatigue severity subscale of the Multidimensional Assessment of Fatigue was used to assess fatigue; scores range from 0–10 (where 0 = no fatigue and 10 = most severe fatigue) [18]. A score ≥ 7 was classified as severe fatigue. Gait speed cut points (adjusted for height and sex) from Fried et al. [17,3] were used to define slow 4-m gait speed. For men, slow 4-m gait speed was defined as: ≥7sec for height ≤1.73m, and ≥6sec for height >1.73m. For women, slow 4-m gait speed was defined as: ≥7sec for height ≤1.59m, and ≥6sec for height >1.59m. Physical activity was assessed by self-report with the long form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [19]. The IPAQ has been used and validated in a number of populations [20,21]. The scoring protocol provides a cut point by which individuals’ weekly energy expenditure can be categorized as low, moderate, or high. Individuals who expended fewer than 600 metabolic equivalent (MET) minutes per week were classified as having low physical activity [20,19].

Physical Function

Two measures that assess different aspects of self-reported physical function were performed. The first measure was the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) (scores range from 0-3, with higher scores reflecting greater limitations) [22]. The second measure was the Valued Life Activities (VLA) disability scale [23], (scores range from 0-3, with higher scores reflecting greater disability). Activities that individuals deem unimportant to them or that they do not perform for reasons unrelated to RA are not rated and are not included in scoring.

Other Variables

Sociodemographic characteristics (age, race/ethnicity, education, income) and smoking status were obtained from the baseline RA Panel telephone interview. Self-reported RA disease activity was assessed at the visit using the Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Index (RADAI) [24,25]. RADAI scores range from 0-10, with higher scores reflecting greater disease activity. The RADAI has been shown to be reliable and valid [25,24]. Pain was rated on an 11-point numerical rating scale ranging from 0-10 (where 0 = no pain and 10 = extreme pain) [26]. High-sensitivity CRP (CRP) was analyzed by nephelometry and cyclic citrullinated peptide IgG (CCP) by immunoassay at a regional clinical laboratory. Glucocorticoid and tumor necrosis factor inhibitor medication use was assessed at the time of the visit. Blood samples were collected during study visits.

Primary Statistical Analyses

Differences in participant characteristics between frailty categories were tested with ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis, or chi-squared analyses. Linear regression analyses were used to model the association of frailty category with HAQ and VLA scores with and without adjusting for covariates (age, sex, disease duration, hsCRP, use of oral steroids, and pain). Due to the skewed distribution, CRP values were logarithmically transformed to the normal distribution prior to inclusion in regression analyses [27].

Secondary Statistical Analyses

Because grip strength is likely to be affected by RA disease activity and damage, we tested whether the relationship between frailty category and physical function scores was robust to using lower extremity strength in calculating frailty severity. Lower extremity strength (measured as peak torque of knee extension) instead of grip strength was used in assigning frailty category. Participants in the lowest quintile of knee strength, adjusted for sex and BMI, were classified as having low strength. Unlike for grip strength, previously validated cut points of knee extension strength do not exist. This quintile-based approach of assigning knee extension weakness was chosen to correspond to the method used by Fried et al. to derive grip strength cut points [3]. Frailty severity was recalculated using this alternative definition of weakness, and linear regression models were repeated.

To further examine the combined effect of frailty and pain status on physical function, patients were classified as belonging to one of four categories: low pain-not frail, high pain-not frail, low pain-frail, or high pain-frail (Low pain = pain score ≤ 2, high pain = pain score ≥ 3, not frail = robust or pre-frail). Linear regression analyses were used to model the association of frailty-pain category with HAQ and VLA scores with and without adjusting for covariates. Mean adjusted HAQ and VLA scores for each frailty-pain category were compared by pair-wise comparison of margins. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata, version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Subject characteristics

Participant characteristics grouped by frailty category are shown in Table 1. Sixteen individuals were classified as frail, 86 as pre-frail, and 22 as robust. Women were less likely than men to be frail (25 vs 75%, respectively; p=0.002). The frequency of frailty components among participants, for both the primary and secondary analyses, is shown in Table 2. In the primary analysis using the Fried et al cut-points, low BMI and slow 4-meter walk speed were observed in only 3 (2%) and 7 (6%) participants respectively, whereas low grip strength was observed in 93 (75%) of participants.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics Grouped by Frailty Category#

| Overall (n=124) |

Frail (n=16) |

Pre-Frail (n=86) |

Robust (n=22) |

P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 58.0 ± 10.8 | 58.3 ± 10.5 | 58.8 ± 10.9 | 54.7 ± 10.8 | 0.3 |

| Female Sex %(n) | 59 (73) | 25 (4) | 59 (51) | 82 (18) | 0.002 |

| Disease Duration, years | 19.2 ± 10.6 | 19.1 ± 12.8 | 20.0 ± 10.4 | 16.1 ± 9.7 | 0.3 |

| CCP Ab Positivity %(n) | 63 (77) | 63 (10) | 67 (58) | 41 (9) | 0.06 |

| RADAI Score | 2.4 ± 1.7 | 2.8 ± 1.6 | 2.6 ± 1.8 | 1.6 ± 1.3 | 0.05 |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 1.8 (0.7-5.0) | 2.5 (1.2-6.3) | 1.8 (0.7-5.2) | 1.4 (0.8-2.9) | 0.3 |

| Pain Score | 2.4 ± 2.2 | 2.8 ± 1.8 | 2.6 ± 2.3 | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 0.07 |

| Prednisone use, mg/day % (n) | 0.3 | ||||

| 0 | 69 (85) | 75 (12) | 66 (57) | 73(16) | |

| 0.5-4.5 | 11 (14) | 19 (3) | 8 (7) | 18 (4) | |

| 5-9.5 | 11 (14) | 0 (0) | 15 (13) | 5 (1) | |

| 10-14.5 | 4.0 (5) | 0 (0) | 6 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| ≥ 15 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| TNF Inhibitor Use %(n) | 47 (56) | 44 (7) | 48 (41) | 36 (8) | 0.6 |

| Frailty Components | |||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.0 ± 5.5 | 30.9 ± 7.7 | 26.8 ± 5.2 | 24.4 ± 3.0 | 0.001 |

| Grip Strength, kg (n=124) | 17.4 ± 9.3 | 16.4 ± 7.3 | 15.1 ± 7.7 | 27.1 ± 10.2 | <0.0001 |

| Knee Extension, N-m (n=111) | 41.4 ± 14.7 | 38.9 ± 13.4 | 39.6 ± 14.1 | 49.0 ± 15.6 | 0.02 |

| Fatigue Severity Score | 4.8 ± 2.5 | 8.0 ± 1.7 | 4.6 ± 2.3 | 3.5 ± 1.5 | <0.0001 |

| 4-Meter Walking Time (sec) | 4.2 ± 1.6 | 5.3 ± 1.8 | 4.2 ± 1.6 | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 0.004 |

| Low Physical Activity+ %(n) | 31 (38) | 94 (15) | 27 (23) | 0 (0) | <0.0001 |

Values are mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) unless otherwise indicated.

Based on International Physical Activity Questionnaire classification

p-values are for the test of overall difference by frailty severity category tested using either ANOVA, Kruskal Wallis, or Chi-squared test.

Table 2.

Frequency of Frailty Components by Frailty Category among Individuals with Rheumatoid Arthritis#

| Primary Analyses

|

Secondary Analysis

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grip Strength based Frailty* n=124 |

Knee Strength based Frailtyˆ n=111 |

|||||

| Frail | Pre-Frail | Robust | Frail | Pre-Frail | Robust | |

| n=16 | n=86 | n=22 | n=4 | n=57 | n=50 | |

| Low BMI | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Low Grip or Knee Strength | 16 | 77 | 0 | 3 | 22 | 0 |

| High Fatigue Severity | 14 | 16 | 0 | 4 | 20 | 0 |

| Slow 4-Meter Walk | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Low Physical Activity+ | 15 | 23 | 0 | 4 | 28 | 0 |

Values are count of individuals

Based on International Physical Activity Questionnaire classification

Frail= ≥3 physical deficits, Pre-frail= 1-2 physical deficits, Robust= 0 physical deficits [3]

Peak torque of knee extension (Nm) in the lowest quintile (adjusted for BMI and sex) is defined as weak. Knee strength cutpoints (Nm): Men BMI <23.8 – 29.3, BMI 23.8-28 −41.5, BMI 28.1-31.5 – 22.7, BMI>31.5 – 19.1. Women BMI <22.7 – 30.9, BMI 22.7-25 – 34.7, BMI 25.1-28.7 – 25.9, BMI >28.7 – 23.5

Of the 124 participants, 13 (10%) did not complete the knee torque assessment. The most common reasons for non-completion were pain or other pre-defined contraindications to the procedures (e.g., high or low blood pressure).

Association of frailty severity with physical function: primary analyses

In unadjusted and adjusted models, frailty category was statistically significantly associated with differences in VLA scores and trended towards an association with differences in HAQ scores (Table 3). The effect of being frail compared to being robust was associated with a 0.44 worse VLA score (p<0.01) when the effects of all covariates are held constant. Table 4 includes all terms in the adjusted model.

Table 3.

Linear Regression Coefficients (95% CIs) for the Effect of Frailty Category on HAQ and VLA Difficulty Scores among Individuals with Rheumatoid Arthritis (n=124)

| Primary Analyses

|

Secondary Analyses

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grip Strength based Frailtyˆ (n=124) | Knee Strength based Frailtyˆˆ (n=111) | |||

| HAQ | VLA | HAQ | VLA | |

| Frail | 0.24 (−0.12, 0.60) |

0.44 (0.19, 0.69)** |

0.53 (−0.11, 1.18) |

0.80 (0.38, 1.21)*** |

| Pre-Frail | 0.14 (−0.12, 0.39) |

0.17 (−0.01, 0.34) |

0.05 (−0.17, 0.26) |

0.15 (0.01, 0.29)* |

| Robust | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

All models are adjusted for age, sex, disease duration, hsCRP, use of oral steroids, and pain.

Frail= ≥3 physical deficits, Pre-frail= 1-2 physical deficits, Robust= 0 physical deficits [3]

Peak torque of knee extension (Nm) in the lowest quintile (adjusted for BMI and sex) is defined as weak. Knee strength cutpoints (Nm): Men BMI <23.8 – 29.3, BMI 23.8-28 −41.5, BMI 28.1-31.5 – 22.7, BMI>31.5 – 19.1. Women BMI <22.7 – 30.9, BMI 22.7-25 – 34.7, BMI 25.1-28.7 – 25.9, BMI >28.7 – 23.5

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Table 4.

Complete Adjusted Model of Linear Regression Coefficients (95% CIs) for the Effect of Frailty Category, on HAQ and VLA Difficulty Scores among Individuals with Rheumatoid Arthritis (n=124)

| HAQ | VLA | |

|---|---|---|

| Frailty Category | ||

| Frail | 0.24 (−0.12, 0.60) |

0.44 (0.19, 0.69)** |

| Pre-Frail | 0.14 (−0.12, 0.39) |

0.17 (−0.01, 0.34) |

| Robust | Reference | Reference |

| Age (yrs) |

0.01 (0.001, 0.02)* |

0.0003 (−0.006, 0.006) |

| Female Sex | −0.06 (−0.26, 0.14) |

−0.09 (−0.23, 0.05) |

| Disease Duration (yrs) |

0.01 (0.0005 0.02)* |

0.005 (−0.001, 0.01) |

| ln(hsCRP) |

0.10 (0.02, 0.17)* |

0.01 (−0.04, 0.07) |

| Oral Steroid Use (yes/no) | −0.15 (−0.35, 0.04) |

0.004 (−0.13, 0.14) |

| Pain Severity (0-10) |

0.11 (0.06, 0.16)*** |

0.10 (0.07, 0.14)*** |

Frail= ≥3 physical deficits, Pre-frail= 1-2 physical deficits, Robust= 0 physical deficits [3]

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Association of frailty with physical function: secondary analyses

To address potential unmeasured effects of RA disease activity and damage on the grip strength, we examined whether the effect of frailty category on HAQ and VLA scores was robust to using lower extremity strength in calculating frailty severity. When using weak knee extension strength instead of grip strength to assign frailty category, the overall trends remained largely unchanged (Table 3). The effect of being frail compared to being robust was associated with a 0.8 worse VLA score (p<0.001) when the effects of all covariates are held constant.

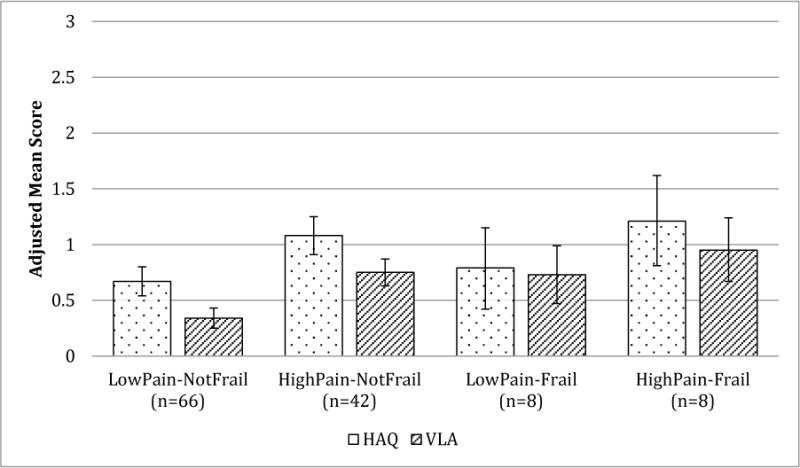

Because pain was also observed to be an important determinate of self-reported physical function in our cohort of individuals with RA (Table 4), we examined the combined effect of frailty (frail vs not frail) and pain (low pain vs high pain) on HAQ and VLA scores by comparing mean adjusted HAQ and VLA scores between four categories of frailty-pain combinations. Mean adjusted HAQ and VLA scores by frailty-pain category are depicted in Figure 1. Mean adjusted HAQ score for low pain-not frail participants [0.67 (0.54, 0.80] was statistically significantly lower than that of high pain-not frail [1.08 (0.91, 1.25] and high pain-frail [1.21 (0.81, 1.62] participants, (all p<0.05). Mean adjusted VLA score for low pain-not frail participants [0.34 (0.25, 0.43] was statistically significantly lower than that of high pain-not frail [0.75 (0.63, 0.87], low pain-frail [0.73 (0.47, 0.99], and high pain-frail [0.95 (0.67, 1.24] participants, (all p<0.05).

Figure 1. Adjusted Mean HAQ and VLA Score by Pain and Frailty Status.

Scores are adjusted for age, sex, disease duration, hsCRP, use of oral steroids, and pain.

Low pain defined as pain score ≤2. High pain defined as pain score ≥ 3. Not frail defined as being robust or pre-frail.

Frail= ≥3 physical deficits, Pre-frail= 1-2 physical deficits, Robust= 0 physical deficits [3]

Error bars depict 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

We observed that frailty is common among adults with RA. Moreover, being frail compared to being robust is associated with worse self-reported physical function, even when adjusting for covariates including pain and systemic inflammation. To our knowledge this is the first study to demonstrate that a validated definition of frailty 1.) can be applied to a non-geriatric, adult RA cohort and 2.) that this definition of frailty identifies increased risk of reduced self-reported physical function. Identifying potential, novel determinants of reduced physical function in RA is important because even despite the increasing number of available therapies, reduced physical function and health related quality of life remain common in RA.

The prevalence of frailty among this non-geriatric RA cohort is comparable to, if not greater than, that of older geriatric cohorts. Among our cohort, with an average age of 58 years old, the prevalence of frailty was 13%, compared with an average prevalence of 4-11% in geriatric cohorts that are at least 10 years older [17,4]. Pre-frailty was much more prevalent (69%) in this RA cohort than in geriatric cohorts (40-55%) [17,4]. The prevalence of frailty and pre-frailty observed in this RA cohort are greater than those observed in a cohort of elderly patients with osteoarthritis (10% and 51%, respectively) [28] and are comparable to those observed in cohort of patients with chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) that is on average 10 years older (25% and 51%, respectively) [29]. When frailty status was determined using knee strength, rather than grip strength, the prevalence of frailty decreased to 3%, which is still comparable to that in geriatric cohorts. Frailty is associated with increased risk of poor health outcomes, including reduced physical function and death in geriatric populations [17,4,3]. In addition to demonstrating that frailty and pre-frailty are common among individuals with RA, the current study also demonstrates that, in cross-sectional analysis, frailty is associated with reduced self-reported physical function. Future studies will need to examine longitudinal relationships between frailty and health outcomes in RA.

Certain characteristics are more common among frail than non-frail individuals with RA in our cohort. We observed that women are less likely than men to be frail. Among elderly cohorts the reverse trend has been observed, that women are more likely than men to be frail [3]. However, among individuals with COPD, men are more likely to be frail than women [29]. Further studies will need to examine whether the gender associations with frailty may differ between elderly and non-elderly cohorts with chronic, inflammatory disease. In addition, frail individuals in the present RA cohort were more likely to be obese. This observation corroborates mounting data in which obesity is strongly associated with an increased risk of frailty in both elderly and chronic disease cohorts [30–33]. Moreover, sarcopenic obesity, the combination of low lean mass and high fat mass, is also associated with frailty in older adults [34,35]. In RA, sarcopenic obesity is common and is associated with worse physical function [36,7,37]. Thus, in chronic inflammatory conditions such as RA, CHF, and CKD, it is possible that other definitions of frailty, accounting for both obesity and sarcopenia, may have greater relevance and stronger associations with clinical outcomes. Future studies need to examine whether the relationship of body composition with frailty differs between RA and other populations. Lastly, we observed that weak grip strength, as defined by the Fried et al. cut points [17], is common among individuals with RA.

Our observation that the frailty phenotype described by Fried et al. [17,3] is associated with worse self-reported physical function among adults with RA suggests that frailty may be an important determinant of physical function in RA. Individuals with RA, compared to those without RA, experience increased muscle atrophy and weakness, symptoms of fatigue, and decreased physical activity [7–11]. Therefore, individuals with RA are likely to be at increased risk of frailty. We observe that frailty is likely common in RA and that frail individuals with RA may be at particular risk for reduced physical function. Moreover, the frail-RA state may represent a phenotype with unique associations with physical function outcomes and unique treatment responses. Thus, understanding relationships between frailty and reduced physical function in RA has the potential to inform studies of interventions to help prevent reduced physical function in these patients. Additional studies, including longitudinal analyses of the relationships between frailty and physical function in RA, will need to test each of these hypotheses.

The observed associations between frailty and differences in physical function, measured by the VLA, are clinically significant. The minimum clinically importance difference (MCID) for the HAQ among individuals with RA is approximately 0.22 [38,39]. The MCID for the VLA Difficulty assessment is not established. However the MCID for health-related quality of life measures can be estimated as a one-half standard deviation (SD) difference [40]. On the VLA Difficulty assessment, with SD of 0.6 among individuals with RA, the MCID therefore corresponds to 0.3 [41]. In adjusted analyses, we observed that being frail compared to being robust was associated with an average 0.44 point (0.19, 0.69) increase in VLA score (Table 3). The point estimate for the effect of being frail compared to being robust was an average 0.24 (−0.12, 0.60), which approached statistical significance. Being frail, compared to being robust, therefore appears to be associated with differences in HAQ and VLA Difficulty scores that equal or exceed the MCID, which suggests that these are clinically important relationships.

In secondary analyses, we tested whether the relationship between frailty and HAQ and VLA Difficulty scores was robust to using weak knee extension strength rather than weak grip strength in assigning frailty category. Muscle weakness, measured by grip strength, is one of the components of the frailty phenotype developed by Fried et al. [17,3]. However, measuring grip strength in RA has the potential to be confounded by RA involvement of the hands. When using weak knee extension strength rather than weak grip strength to assign frailty category, the overall relationships between frailty and HAQ and VLA Difficulty scores remained unchanged. In fact, the point estimates of the effects appear to be greater in magnitude compared those observed in the primary analysis. This observation suggests that muscle weakness is contributing to the relationship between frailty and self-reported physical function in RA, and it is not simply the result of RA manifestations in the hands. Further studies will need to directly examine the influence of disease activity on the relationship between frailty category and physical function in RA. Lastly, this observation corroborates prior studies that demonstrate the contribution of muscle weakness to reduced physical function among individuals with rheumatologic disease [15,16].

Pain, like frailty category, was also observed to be an important determinate of self-reported physical function in our cohort of individuals with RA (Table 4). In secondary analysis, we observed that the effect of having increased pain on HAQ and VLA Difficulty scores was similar to that of being frail (Figure 1). While additional studies will need to continue to examine relationships between frailty, pain, and physical function in RA, our findings suggest that both frailty and pain are important determinates of physical function in RA and that interventions to improve physical function may need to address both pain and frailty.

To begin to tease out relationships of individual components of the Fried frailty phenotype with physical function in RA, we performed post-hoc exploratory analyses examining the contribution of each frailty component to overall effect on HAQ and VLA scores. The only consistent trend was observed for high fatigue severity, which increased the R2 of the model of VLA scores from 0.36 to 0.41 (likelihood ratio test, p=0.001). We observed a similar trend with the model of HAQ scores, but this trend did not reach statistical significance (p=0.1). Our study was not designed or powered to address this specific question, and future studies are needed to directly examine the contribution of individual frailty components to effects on physical function. Moreover, we highlight that while the Fried frailty phenotype has been studied in other chronic diseases, such as congestive heart failure and chronic kidney disease [4–6], further studies are needed to test the use of this composite frailty construct and its relationships with clinical outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis as these relationship may be unique in RA.

Our study has potential limitations. This is an observational, cross-sectional study, and we did not have data available from a control comparison group of individuals without RA. In addition, because the assessment of frailty relies on an in-person assessment, it is possible that the most impaired individuals are not captured in the present study. Moreover, it is possible that excluding individuals with missing grip strength data (n=17) may bias results of the primary analysis. Compared to individuals who completed the grip strength assessment, those who did not had higher RADAI scores (3.8 ± 1.8 vs. 2.4 ± 1.7, p=0.002), higher pain scores (3.8 ± 2.0 vs. 2.4 ± 2.2, p=0.009), higher fatigue severity (6.3 ± 2.5 vs. 4.8 ± 2.5, p=0.02), and higher prevalence of low physical activity (59% vs. 29%, p=0.02). There was no difference in age, prevalence of female gender, disease duration, prevalence of CCP antibody, hsCRP, BMI, or 4-m gait speed between the two groups (data not shown). These trends of possible under-representation of the most ill individuals would tend to bias the observed results toward the null. The true effect of frailty on HAQ and VLA scores may be greater than that which we observed. That our RA cohort has relatively longstanding (mean disease duration = 19 years) and relatively well-controlled disease (mean RADAI = 2.4), may limit generalizability. Lastly, the analyzed outcomes do not include any non-patient reported measures of physical function.

There are also strengths of our study. This is one of the first studies of RA to document the relationship between frailty and differences in self-reported physical function. We used standardized, objective assessments to quantify upper and lower extremity muscle strength in assessing frailty and its relationship to physical function.

In summary, we observed that a validated phenotype of frailty is common among non-geriatric adults with RA and is associated with clinically significant differences in self-reported physical function, as measured by the VLA Difficulty assessments. Moreover, effects of frailty category on VLA scores persisted when knee strength, rather than grip strength, was used to assign frailty category suggesting that the relationship is robust to potential confounding effects of RA involvement of the hands.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the patients whose participation made this study possible.

Funding: This research was supported by NIH/NIAMS grant P60 AR053308 and by NIH/NCRR UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131, and by the Russell/Engleman Rheumatology Research Center.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

James S. Andrews, Acting Instructor, Division of Rheumatology, University of Washington.

Laura Trupin, Division of Rheumatology, University of California San Francisco.

Edward H. Yelin, Professor, Division of Rheumatology, University of California San Francisco.

Catherine L. Hough, Associate Professor, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, University of Washington

Kenneth E. Covinsky, Professor, University of California San Francisco.

Patricia P. Katz, Professor, Division of Rheumatology, University of California San Francisco.

References

- 1.Curtis JR, Shan Y, Harrold L, Zhang J, Greenberg JD, Reed GW. Patient perspectives on achieving treat-to-target goals: a critical examination of patient-reported outcomes. Arthritis care & research. 2013;65(10):1707–1712. doi: 10.1002/acr.22048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz PP, Radvanski DC, Allen D, Buyske S, Schiff S, Nadkarni A, Rosenblatt L, Maclean R, Hassett AL. Development and validation of a short form of the valued life activities disability questionnaire for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis care & research. 2011;63(12):1664–1671. doi: 10.1002/acr.20617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA, Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research G Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2001;56(3):M146–156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cawthon PM, Marshall LM, Michael Y, Dam TT, Ensrud KE, Barrett-Connor E, Orwoll ES, Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Research G Frailty in older men: prevalence, progression, and relationship with mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(8):1216–1223. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reeves GR, Whellan DJ, Patel MJ, O’Connor CM, Duncan P, Eggebeen JD, Morgan TM, Hewston LA, Pastva AM, Kitzman DW. Comparison of Frequency of Frailty and Severely Impaired Physical Function in Patients >/=60 Years Hospitalized With Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Versus Chronic Stable Heart Failure With Reduced and Preserved Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction. The American journal of cardiology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roshanravan B, Khatri M, Robinson-Cohen C, Levin G, Patel KV, de Boer IH, Seliger S, Ruzinski J, Himmelfarb J, Kestenbaum B. A prospective study of frailty in nephrology-referred patients with CKD. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2012;60(6):912–921. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker JF, Von Feldt J, Mostoufi-Moab S, Noaiseh G, Taratuta E, Kim W, Leonard MB. Deficits in muscle mass, muscle density, and modified associations with fat in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis care & research. 2014;66(11):1612–1618. doi: 10.1002/acr.22328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giles JT, Bartlett SJ, Andersen RE, Fontaine KR, Bathon JM. Association of body composition with disability in rheumatoid arthritis: impact of appendicular fat and lean tissue mass. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2008;59(10):1407–1415. doi: 10.1002/art.24109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kramer HR, Fontaine KR, Bathon JM, Giles JT. Muscle density in rheumatoid arthritis: associations with disease features and functional outcomes. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2012;64(8):2438–2450. doi: 10.1002/art.34464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roubenoff R. Rheumatoid cachexia: a complication of rheumatoid arthritis moves into the 21st century. Arthritis research & therapy. 2009;11(2):108. doi: 10.1186/ar2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz P, Margaretten M, Trupin L, Schmajuk G, Yazdany J, Yelin E. Role of Sleep Disturbance, Depression, Obesity, and Physical Inactivity in Fatigue in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis care & research. 2016;68(1):81–90. doi: 10.1002/acr.22577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz PP, Yazdany J, Trupin L, Schmajuk G, Margaretten M, Barton J, Criswell LA, Yelin EH. Sex differences in assessment of obesity in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis care & research. 2013;65(1):62–70. doi: 10.1002/acr.21810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO, 3rd, Birnbaum NS, Burmester GR, Bykerk VP, Cohen MD, Combe B, Costenbader KH, Dougados M, Emery P, Ferraccioli G, Hazes JM, Hobbs K, Huizinga TW, Kavanaugh A, Kay J, Kvien TK, Laing T, Mease P, Menard HA, Moreland LW, Naden RL, Pincus T, Smolen JS, Stanislawska-Biernat E, Symmons D, Tak PP, Upchurch KS, Vencovsky J, Wolfe F, Hawker G. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2010;62(9):2569–2581. doi: 10.1002/art.27584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts HC, Denison HJ, Martin HJ, Patel HP, Syddall H, Cooper C, Sayer AA. A review of the measurement of grip strength in clinical and epidemiological studies: towards a standardised approach. Age and ageing. 2011;40(4):423–429. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andrews JS, Trupin L, Schmajuk G, Barton J, Margaretten M, Yazdany J, Yelin EH, Katz PP. Muscle strength predicts changes in physical function in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis care & research. 2015 doi: 10.1002/acr.22560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrews JS, Trupin L, Schmajuk G, Barton J, Margaretten M, Yazdany J, Yelin EH, Katz PP. Muscle strength, muscle mass, and physical disability in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis care & research. 2015;67(1):120–127. doi: 10.1002/acr.22399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bandeen-Roche K, Xue QL, Ferrucci L, Walston J, Guralnik JM, Chaves P, Zeger SL, Fried LP. Phenotype of frailty: characterization in the women’s health and aging studies. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2006;61(3):262–266. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hewlett S, Dures E, Almeida C. Measures of fatigue: Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Multi-Dimensional Questionnaire (BRAF MDQ), Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Numerical Rating Scales (BRAF NRS) for severity, effect, and coping, Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire (CFQ), Checklist Individual Strength (CIS20R and CIS8R), Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS), Functional Assessment Chronic Illness Therapy (Fatigue) (FACIT-F), Multi-Dimensional Assessment of Fatigue (MAF), Multi-Dimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI), Pediatric Quality Of Life (PedsQL) Multi-Dimensional Fatigue Scale, Profile of Fatigue (ProF), Short Form 36 Vitality Subscale (SF-36 VT), and Visual Analog Scales (VAS) Arthritis care & research. 2011;63(Suppl 11):S263–286. doi: 10.1002/acr.20579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, Pratt M, Ekelund U, Yngve A, Sallis JF, Oja P. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2003;35(8):1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown WJ, Trost SG, Bauman A, Mummery K, Owen N. Test-retest reliability of four physical activity measures used in population surveys. Journal of science and medicine in sport/Sports Medicine Australia. 2004;7(2):205–215. doi: 10.1016/s1440-2440(04)80010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagstromer M, Oja P, Sjostrom M. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): a study of concurrent and construct validity. Public health nutrition. 2006;9(6):755–762. doi: 10.1079/phn2005898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, Holman HR. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1980;23(2):137–145. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz P, Morris A, Trupin L, Yazdany J, Yelin E. Disability in valued life activities among individuals with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2008;59(4):465–473. doi: 10.1002/art.23536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stucki G, Liang MH, Stucki S, Bruhlmann P, Michel BA. A self-administered rheumatoid arthritis disease activity index (RADAI) for epidemiologic research. Psychometric properties and correlation with parameters of disease activity. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1995;38(6):795–798. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fransen J, Langenegger T, Michel BA, Stucki G. Feasibility and validity of the RADAI, a self-administered rheumatoid arthritis disease activity index. Rheumatology. 2000;39(3):321–327. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP) Arthritis care & research. 2011;63(Suppl 11):S240–252. doi: 10.1002/acr.20543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giles JT, Bartlett SJ, Andersen R, Thompson R, Fontaine KR, Bathon JM. Association of body fat with C-reactive protein in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2008;58(9):2632–2641. doi: 10.1002/art.23766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castell MV, van der Pas S, Otero A, Siviero P, Dennison E, Denkinger M, Pedersen N, Sanchez-Martinez M, Queipo R, van Schoor N, Zambon S, Edwards M, Peter R, Schaap L, Deeg D. Osteoarthritis and frailty in elderly individuals across six European countries: results from the European Project on OSteoArthritis (EPOSA) BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2015;16:359. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0807-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maddocks M, Kon SS, Canavan JL, Jones SE, Nolan CM, Labey A, Polkey MI, Man WD. Physical frailty and pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD: a prospective cohort study. Thorax. 2016 doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johansen KL, Dalrymple LS, Delgado C, Kaysen GA, Kornak J, Grimes B, Chertow GM. Association between body composition and frailty among prevalent hemodialysis patients: a US Renal Data System special study. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2014;25(2):381–389. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013040431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mezuk B, Lohman MC, Rock AK, Payne ME. Trajectories of body mass indices and development of frailty: Evidence from the health and retirement study. Obesity. 2016 doi: 10.1002/oby.21572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reinders I, Visser M, Schaap L. Body weight and body composition in old age and their relationship with frailty. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care. 2017;20(1):11–15. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Esquinas E, Jose Garcia-Garcia F, Leon-Munoz LM, Carnicero JA, Guallar-Castillon P, Gonzalez-Colaco Harmand M, Lopez-Garcia E, Alonso-Bouzon C, Rodriguez-Manas L, Rodriguez-Artalejo F. Obesity, fat distribution, and risk of frailty in two population-based cohorts of older adults in Spain. Obesity. 2015;23(4):847–855. doi: 10.1002/oby.21013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirani V, Naganathan V, Blyth F, Le Couteur DG, Seibel MJ, Waite LM, Handelsman DJ, Cumming RG. Longitudinal associations between body composition, sarcopenic obesity and outcomes of frailty, disability, institutionalisation and mortality in community-dwelling older men: The Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project. Age and ageing. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scott D, Seibel M, Cumming R, Naganathan V, Blyth F, Le Couteur DG, Handelsman DJ, Waite LM, Hirani V. Sarcopenic Obesity and Its Temporal Associations With Changes in Bone Mineral Density, Incident Falls, and Fractures in Older Men: The Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2016 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baker JF, Long J, Ibrahim S, Leonard MB, Katz P. Are men at greater risk of lean mass deficits in rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis care & research. 2015;67(1):112–119. doi: 10.1002/acr.22396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weber D, Long J, Leonard MB, Zemel B, Baker JF. Development of Novel Methods to Define Deficits in Appendicular Lean Mass Relative to Fat Mass. PloS one. 2016;11(10):e0164385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wells GA, Tugwell P, Kraag GR, Baker PR, Groh J, Redelmeier DA. Minimum important difference between patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the patient’s perspective. The Journal of rheumatology. 1993;20(3):557–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Redelmeier DA, Lorig K. Assessing the clinical importance of symptomatic improvements. An illustration in rheumatology. Archives of internal medicine. 1993;153(11):1337–1342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Medical care. 2003;41(5):582–592. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Katz PP, Morris A, Yelin EH. Prevalence and predictors of disability in valued life activities among individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2006;65(6):763–769. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.044677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]