Abstract

Introduction:

Only a few studies from Arab Muslim countries address do-not-resuscitate (DNR) practice. The knowledge of physicians about the existing policy and the attitude towards DNR were surveyed.

Objective:

The objective of this study is to identify the knowledge of the participants of the local DNR policy and barriers of addressing DNR including religious background.

Methods:

A questionnaire has been distributed to Emergency Room (ER) and Intensive Care Unit (ICU) physicians.

Results:

A total of 112 physicians mostly Muslims (97.3%). About 108 (96.4%) were aware about the existence of DNR policy in our institute. 107 (95.5%) stated that DNR is not against Islamic. Only (13.4%) of the physicians have advance directives and (90.2%) answered they will request to be DNR if they have terminal illness. Lack of patients and families understanding (51.8%) and inadequate training (35.7%) were the two most important barriers for effective DNR discussion. Patients and families level of education (58.0%) and cultural factors (52.7%) were the main obstacles in initiating a DNR order.

Conclusions:

There is a lack of knowledge about DNR policy which makes the optimization of DNR process difficult. Most physicians wish DNR for themselves and their patients at the end of life, but only a few of them have advance directives. The most important barriers for initializing and discussing DNR were lack of patient understanding, level of education, and the culture of patients. Most of the Muslim physicians believe that DNR is not against Islamic rules. We suggest that the DNR concept should be a part of any training program.

Keywords: Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, do-not-resuscitate, physician attitude, survey

INTRODUCTION

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) initially called the closed-chest cardiac massage was first introduced by Kouwenhoven in 1960.[1] CPR became mandatory for all hospitalized patients suffering from cardiac arrest.[2] Later on, the use of CPR for all patients was questioned due to low survival rate and poor neurological outcome,[3] and the concept of do-not-resuscitate (DNR) for terminally ill patients became part of medical practice; however, it was always one of the most difficult decisions to be made by physicians.

Many barriers existed when in regards to DNR orders including; lack of knowledge about DNR decision making, physicians being uncomfortable in opening the discussion with the patient or his family,[4] and religious and cultural differences among physicians and patients.[5,6,7] There is a lack of research about the DNR area in most of the Arab and Muslim countries, and the attitude of Muslim physicians for DNR is not very well known in spite of the presence of Fatwa (a legal opinion or ruling issued by an Islamic scholar).[8,9] Our institute is one of the few hospitals in Saudi Arabia with a formal DNR policy, which has been in effect since 1998.

A questionnaire has been distributed among ER and Intensive Care Unit (ICU) physicians as they are mostly dealing with patients in critical medical illnesses who are more likely to develop cardiopulmonary arrest.

The survey was designed in an attempt to identify the attitude, the religious belief, advance directives of the participating physicians and possible barriers, and obstacles in addressing DNR status of the patients.

Objectives

We observed substandard practice of DNR concept in our institute and some conflicts are occasionally rising between physicians themselves and with the family or patients regarding DNR order initiation, discussion, documentation, and post-DNR measures.

This questionnaire is meant to identify the knowledge of the participating physicians about the existing local policy and guidelines of DNR order as part of the medical practice.

We are also aiming to identify possible barriers and obstacles for practicing DNR concept which might improve the process of initiating DNR order and managing patients who were labeled as DNR.

The impact of Islamic religion and personal belief on the attitude of physicians toward DNR order were also included together with the advance directives of the participating physicians.

METHODS AND DESIGN

Settings and statistical analysis

Our institute is a 1200-bed tertiary care center and teaching hospital located in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and affiliated with King Saud Bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences.

This questionnaire has been distributed either manually or by E-mail to 154 physicians, 71 physicians from ER department and 41 physicians from ICU department. The response rate among all physicians was 73%.

The answers to the questionnaire were collected, tabulated, and analyzed using IBM, SPSS software Version 22 (property of IBM Corp. 1989, 2013 Chicago IL, USA).

Data were analyzed regarding frequencies and descriptive statistics, and the results are expressed as percentages.

Questionnaire

The data collected included demographics [Appendix 1 (256.8KB, pdf) ] (age, sex, religion, income, specialty training, and years of experience), awareness about the DNR policy, advance directives of the participants, and the importance of guidelines and training in the concept of DNR.

Appendix 1: A survey regarding do-not-resuscitate among Intensive Care Unit/ER– doctors

Ethical approval

The protocol of the study has been approved by the Internal Review Board.

Local policy guidelines for do-not-resuscitate

There are no existing National guidelines for DNR in the KSA; every hospital has its own local guidelines; however recently, there is ongoing project by MOH to establish a National policy for DNR for MOH and non-MOH hospitals, yet to be approved by the Saudi Health Council.

The policy concerning DNR order for terminally ill patients in our institute has been established based on fatwa (a legal opinion or ruling issued by an Islamic scholar) number 12086, dated June 30, 1988, Ethics of the Medical Profession, 2nd edition (2003) by Saudi Commission for Health Specialties and approved as per the Joint Commission International standards (2006).

Three physicians, including the attending, another consultant, and a staff physician, should sign the DNR order electronically in the electronic healthcare system after discussion with the family or the patient, in which the system will flag the patient automatically as DNR, and the order will be valid for 6 months. Recently, a new goals of care form has been developed which will be signed by the patient or his surrogate.

In case of conflict between the family/patient and the physician, the issue might be escalated to the ethics committee which will address the matter further.

If the patient is labeled DNR, no CPR, ICU admission, intubation, or inotropic support will be offered to the patient; however, all other modalities of treatment might be given including support and comfort care.

RESULTS

A total of 112 physicians participated in this questionnaire.

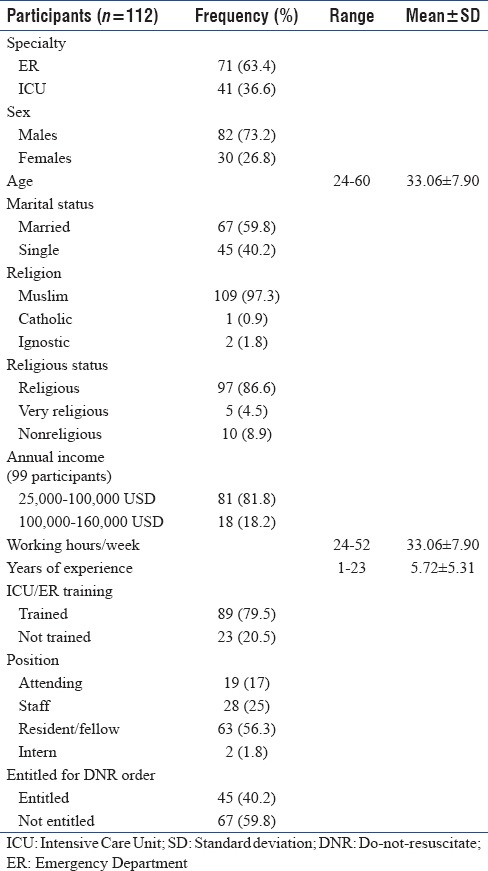

Demographics features of the participants are shown in Table 1. 71 (63.4%) of the responders were ER physicians and 41 (36.6) were ICU physicians. 73.2% of all the participants were males and 26.8% were females with the age ranging from 24 to 60 years with the mean of 33.06 + 7.90 standard deviation (SD), 59.8% are married and 39% are single and the Majority 97.3% are Muslim religion. among the participants 86.6% consider themselves reasonably religious, 8.9% nonreligious and 4.5% very religious.

Table 1.

Demographic data of the participants

Among 112 participants 99 (88.3%) revealed their income and 13 (11.7%) refused to reveal their income. The majority of those who revealed their income (81.8%) earn 25,000–100,000 USD/year and (18.2%) earn more than 100,000 USD/year.

The working hours of the participants range from 24 to 52 h/week with a mean of 36.33 ± 8.26.

The years of experience ranging from 1.0 to 23.0 years with the mean of 5.72 ± 5.31

History of specialty training showed 89 (79.5%) are trained in ICU/ER and 23 (20.5%) did not have formal specialty training in ICU/ER.

The position of the participants was as follows: 19 (17%) were attending, 28 (25%) ICU/ER staff, 63 (56.3%) residents and fellow in training, and 2 (1.8%) interns.

45 (40.2%) were eligible to initiate DNR order, and 67 (59.8%) were not entitled to initiate DNR order.

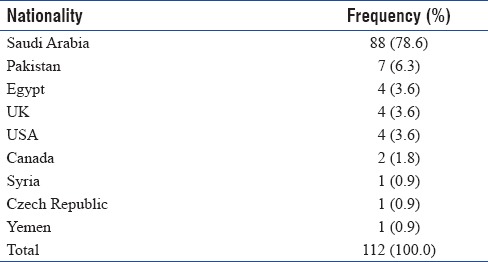

Nationality distribution of the participants is shown in [Table 2].

Table 2.

Nationality distribution among participants

Among the participants, 108 (96.4%) were aware about existence of DNR policy in our institute but (67%) did not read the policy and (54.5%) were not familiar of the electronic form of DNR in our hospital electronic healthcare system.

As per our DNR policy, 3 physicians including the attending, one other consultant and one staff should sign the electronic form to be legally flagged in the system. 80 participants (71.4%) believed that three physicians are needed to complete the DNR order, but 35 (31.2%) thought that the DNR order should be made only by Intensivist and 13 (11.6%) stated that DNR should be made by any competent physician.

The validity of DNR in the system as per our policy should be 6 months, however, only 67 (59.8%) of the participants knew the correct answer.

A total of 70 participants (62.5%) answered that family/patient approval of DNR is not a must, and 77 (68.8%) did not know what the policy is stating and what would be the right action in case if the family or the patient refuses the DNR order, and there is a conflict between the family and the medical staff.

About 109 (97.3%) participants responded that DNR is not against their religious believes and 107 (95.5%) stated that DNR is not against Islamic rules, however, only 52 (46.4) participants were aware about Islamic decree (Fatwa) about DNR.

Almost half of the participants (54.4%) were never involved in discussing DNR with patients/family.

The majority of the participants (85.7%) preferred to open the discussion of DNR by asking about the understanding of patient's illness and medical condition.

Of the participants who were actually involved in the discussion of DNR, the average time they spent was 14.3 min with range of 10–25 min and (44.6%) were not comfortable during discussion.

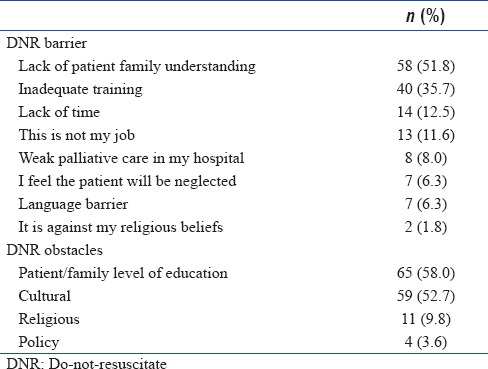

The barriers and obstacles for opening DNR discussion are summarized in Table 3, and more than one answer was allowed for these questions.

Table 3.

Do-not-resuscitate barriers and obstacles

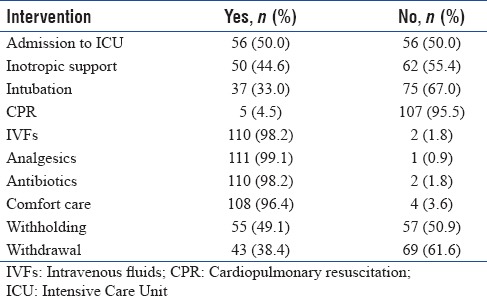

After completion of DNR process, there was an agreement among participants that patients labeled as DNR should not receive CPR but may receive antibiotics, intravenous fluid, comfort care, and analgesics. There were conflicting answers for other invasive therapy as shown in [Table 4].

Table 4.

Knowledge about interventions postcompletion of do-not-resuscitate order

For an interpretation that “DNR means no care, the majority of participants (83.9%) disagree about that statement, but almost half (57.1%) of the participants thought that DNR patients might deliberately receive substandard level of care.

Despite the fact that there was agreement that DNR is a reasonable action for a dying patient there was no agreement on withholding and withdrawing of life-sustaining measures [Table 4].

Only 62% of the participants were aware of applying the concept of futile treatment in addressing DNR and there were variations among participants in defining the term “futile treatment”.

There was an agreement to a great extent about the importance of training during residency for DNR concept, the presence of clear guidelines, educational programs involving the nurses in the decision, and presence of emotional counseling and support services for the staff.

However, (78.5%) of the participants were not aware about the presence of ethics committee in our institute nevertheless (88.3%) were not willing to use them in DNR context.

Surprisingly, only (13.4%) of the physicians have advance directives, but (86%) of them believes that every patient should have advance directives.

The physicians were asked that if they developed a terminal illness what course of action would they choose for themselves and (90.2%) answered that they will request to be placed as DNR, but they were not certain about ICU admission and being put on ventilators.

Two-thirds of the participants stated that they answered this survey because they appreciate the quality of life rather than the value of life.

DISCUSSION

Results of this study revealed that some interesting information on the knowledge and attitudes of physicians toward DNR. One interesting finding is that almost half of the participants were never involved in discussing DNR with patients or family and this is probably due to the fact that 83% of the responders in our study were registrars and residents and fellows in training. Our results were similar to other studies from Saudi Arabia and Portugal,[10,11,12,13,14] which indicate that there is a need for developing a structured residency program curriculum to address resident skills in end-of-life care, and the DNR concept should be part of any training programs.

The compliance of documentation of DNR order in our institute is not up to the optimum.[15] In spite of the presence of local policy and guidelines since 1998 in our institute, the findings of this study revealed that most of the physicians are aware about the existence of such policy; two thirds of the physicians did not read the detailed policy which raise the question about the efficacy of DNR practice in our institute. One study from Saudi Arabia,[16] found that when considering DNR, physicians in Saudi Arabia shared with their counterparts in the West in many features, notably caring about dignity of the patient, but were also concerned about the religious and the legal stand; however, he related this issue to the absence of clear local policies and guidelines, and in our study, a clear policy is available in our institute, and religion was not a factor of concern.

The perception of the physicians participated in this survey about their advance directives and DNR at the end of their lives was similar to what has been found by other researchers, one being from Saudi Arabia,[10,17,18] as most of the physicians are in favor of having a DNR order for themselves if they acquire a terminal illness. Majority of the physicians prefer the DNR order to be a physician-directed decision, yet they believe that every patient should have advance directives; however, few of the participating physicians have advance directives. Should it be concerning that doctors continue to provide high-intensity care for terminally ill patients but personally forego such care for themselves at the end of life? There was a concern among participants that DNR patients might receive substandard level of care. This concern was also shown in other studies.[19] This highlights the importance of defining the goal of care post-DNR order. Religion (Islam in our study) was not a limiting factor in addressing DNR. Almost all participating physicians (97.3%) stated that DNR is not against their religious beliefs compared to (66.8) in one study done by Saeed et al. where the religious aspects of end-of-life care among 461 Muslim physicians in the US and other countries;[20] were studied. However, only 52 (46.4%) of the participants were aware about the Committee for Islamic Research and Issuing Fatwa in Saudi Arabia issued Fatwa (decree) No. 12086 on 28/3/1409 (1989) based on questions raised using resuscitative measures.

In comparison, one survey done among outpatients, participants expressed divided opinions regarding the association of religion (namely, Islam) with the DNR order, 34.4% endorsing its agreement with Islamic regulations, 34.3% pointing to disagreement, and 31.3% expressing neutrality on the issue.[21]

However, the Islamic religion like other religions shares the controversy about other aspects of end of life decisions as withholding, withdrawal, organ donation, and euthanasia.[22,23,24]

In the opinion of the participating physicians in this study culture, the patients’ and families’ level of education and lack of understanding and inadequate training of physicians were the main barriers and obstacles for initiation and completion of DNR orders. These findings were similar to two more studies from Saudi Arabia.[25,26]

Culture as an obstacle for DNR decisions was also proved to be a crucial factor in the western culture as shown in ETHICUS, SUPPORT, and ETHICATT studies.[5,27,28]

It seems that more efforts are needed to increase patients’ and their families’ awareness regarding the meaning of a DNR order which will improve the physicians-patients’ communication about such extremely critical issues.

Limitations of the study

Small sample size, single-center including only ICU and ER physicians and no comparison made for some concern of tagging one specialty for the knowledge of DNR policy

The study does not highlight the DNR practice in other centers that lack DNR policy.

Strength

The current study has elucidated the state of awareness regarding the DNR order among the physicians in training in our hospital.

CONCLUSIONS

DNR practice is a very important part of medical practice, currently, the knowledge of the physicians about an existing DNR local policy and guideline is not optimal. Most of the physicians do want DNR for themselves in case of terminal illness. The main barriers for initializing and discussing DNR were patient culture and lack of understanding, but Islam as a religion was not a barrier in addressing DNR.

The awareness about the policy, utilization of the ethics committee, training for junior physicians, national programs for the public, and defining the goals of care post-DNR are principal factors for improvement.

Further studies should be multicentered involving physicians from all different specialties, nationalities, and religions from different Arab countries. Variation will highlight the barriers for DNR practice and help in better implementation of DNR orders in this region of the world.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kouwenhoven WB, Jude JR, Knickerbocker GG. Closed-chest cardiac massage. JAMA. 1960;173:1064–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.1960.03020280004002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McClung JA, Kamer RS. Implications of New York's do-not-resuscitate law. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:270–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007263230411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bedell SE, Delbanco TL, Cook EF, Epstein FH. Survival after cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the hospital. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:569–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198309083091001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stolman CJ, Gregory JJ, Dunn D, Levine JL. Evaluation of patient, physician, nurse, and family attitudes toward do not resuscitate orders. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:653–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sprung CL, Cohen SL, Sjokvist P, Baras M, Bulow HH, Hovilehto S, et al. End-of-life practices in European Intensive Care Units: The Ethicus study. JAMA. 2003;290:790–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.6.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vincent JL. Forgoing life support in Western European Intensive Care Units: The results of an ethical questionnaire. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1626–33. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199908000-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sprung CL, Maia P, Bulow HH, Ricou B, Armaganidis A, Baras M, et al. The importance of religious affiliation and culture on end-of-life decisions in European Intensive Care Units. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:1732–9. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0693-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babgi A. Legal issues in end-of-life care: Perspectives from Saudi Arabia and United States. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2009;26:119–27. doi: 10.1177/1049909108330031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takrouri M, Halwani T. An Islamic medical and legal prospective of do not resuscitate order in critical care medicine. Internet J Health. 2007;1:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mobeireek A. The do-not resuscitate order: Indications on the current practice in Riyadh. Ann Saudi Med. 1995;15:6–9. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1995.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albugami M, Bassil H, Laudon U, Ibrahim A, Elamin A, ElAlem U, et al. Medical residents’ practices and perceptions toward do-not- resuscitate (DNR) order. J Palliat Care Med. 2017;7:295–302. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aljohaney A, Bawazir Y. Internal medicine residents’ perspectives and practice about do not resuscitate orders: Survey analysis in the western region of Saudi Arabia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;6:393–8. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S82948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amoudi AS, Albar MH, Bokhari AM, Yahya SH, Merdad AA. Perspectives of interns and residents toward do-not-resuscitate policies in Saudi Arabia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2016;7:165–70. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S99441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Granja C, Teixeira-Pinto A, Costa-Pereira A. Attitudes towards do-not-resuscitate decisions: Differences among health professionals in a Portuguese hospital. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:555–8. doi: 10.1007/s001340100852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gouda A, Al-Jabbary A. Lian Fong intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:2149–53. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1985-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Mobeireek AF. Physicians’ attitudes towards ‘do-not-resuscitate’ orders for the elderly: A survey in Saudi Arabia. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2000;30:151–60. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(00)00047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tayeb MA, Al-Zamel E, Fareed MM, Abouellail HA. A “good death”: Perspectives of Muslim patients and health care providers. Ann Saudi Med. 2010;30:215–21. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.62836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Periyakoil VS, Neri E, Fong A, Kraemer H. Do unto others: Doctors’ personal end-of-life resuscitation preferences and their attitudes toward advance directives. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beach MC, Morrison RS. The effect of do-not-resuscitate orders on physician decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:2057–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saeed F, Kousar N, Aleem S, Khawaja O, Javaid A, Siddiqui MF, et al. End-of-life care beliefs among Muslim physicians. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2015;32:388–92. doi: 10.1177/1049909114522687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al Sheef MA, Al Sharqi MS, Al Sharief LH, Takrouni TY, Mian AM. Awareness of do-not-resuscitate orders in the outpatient setting in Saudi Arabia. Perception and implications. Saudi Med J. 2017;38:297–301. doi: 10.15537/smj.2017.3.18063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bülow HH, Sprung CL, Reinhart K, Prayag S, Du B, Armaganidis A, et al. The world's major religions’ points of view on end-of-life decisions in the Intensive Care Unit. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:423–30. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0973-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bülow HH, Sprung CL, Baras M, Carmel S, Svantesson M, Benbenishty J, et al. Are religion and religiosity important to end-of-life decisions and patient autonomy in the ICU? The Ethicatt study. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1126–33. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2554-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schenker Y, Tiver GA, Hong SY, White DB. Association between physicians’ beliefs and the option of comfort care for critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1607–15. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2671-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahman MU, Arabi Y, Adhami NA, Parker B, Al-Shimemeri A. The practice of do-not-resuscitate orders in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The experience of a tertiary care center. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:1278–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aldawood AS, Alsultan M, Arabi YM, Baharoon SA, Al-Qahtani S, Haddad SH, et al. End-of-life practices in a tertiary Intensive Care Unit in Saudi Arabia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2012;40:137–41. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1204000116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT principal investigators. JAMA. 1995;274:1591–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sprung CL, Carmel S, Sjokvist P, Baras M, Cohen SL, Maia P, et al. Attitudes of European physicians, nurses, patients, and families regarding end-of-life decisions: The ETHICATT study. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:104–10. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0405-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: A survey regarding do-not-resuscitate among Intensive Care Unit/ER– doctors