Abstract

Hepatitis E virus (HEV), a non-enveloped single stranded RNA virus causes sporadic cases of hepatitis or outbreaks. The disease is generally self-limited although it may cause fulminant hepatitis in pregnant women, elderly, those with underlying chronic hepatitis, immunosuppressed, and transplant recipients. It is transmitted through fecal–oral route and zoonotic transmission. Hepatitis is a main health care problem in Turkey; HBV and HCV prevalences are 4 and 1% respectively. Hepatitis D represents another considerable hepatitis etiology with a prevalence of 5–27%. The information about HEV is not clear. In this systematic review, we aimed to analyze HEV studies reported from Turkey, to determine the current situation of the disease in the country, to delineate the limits of the studies and to determine the future study areas. The prevalence of HEV ranged from 0 to 12.4%. Children had lower prevalence than the adults. The prevalence was determined as 7–8% in pregnant women, 13% in chronic HBV patients, 54% in chronic HCV patients, 13.9–20.6% in patients with chronic renal failure, and ≈ 35% in agriculture workers. Among individuals immigrating form Turkey to Europe, HEV seroprevalence was found 10.3% in Italy and 33.4% in the Netherlands. HEV prevalence seems high in certain risk groups. Although previous studies suggest that Turkey is among the endemic countries of HEV, there are some pitfalls for the analysis of data: the studies are not powered enough to represent the whole population; they did not include immunosuppressed patients and solid organ recipients; and the prevalence of non-A non-B hepatitis was not determined.

Keywords: Hepatitis E virus, Turkey, Prevalence, Systematic review, Travel

Background

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) was first identified in 1983. It causes sporadic cases of hepatitis or outbreaks and the disease is generally self-limited although it may cause fulminant hepatitis in pregnant women, elderly, those with underlying chronic hepatitis, immunosuppressed, and transplant recipients [1, 2]. It is a non-enveloped single stranded RNA virus in the genus Hepevirus and the family Hepeviridae. It has four genotypes. Genotypes 1 and 2 cause disease in humans while genotypes 3 and 4 cause diseases both in humans and animals especially in pigs [3]. HEV can be transmitted waterborne, foodborne, or zoonotic. While fecal–oral route is common in the countries where HEV is endemic, in developing countries, zoonotic transmission is more prevalent and causes sporadic infections [4, 5]. Seroprevalence differs according to the way of transmission. According to World Health Organization (WHO), 20 million HEV infections develop every year, 15% of them being symptomatic [6].

Turkey is a developing country; annual income is 25,275 US$/capita, with a population of 77 million, surface area of 783.563 km2 and with 62.5% agricultural land [7]. Viral hepatitis is a challenging health problem with a significant morbidity. Hepatitis seroprevalence differs among regions probably due to the socio-economical differences. HBV and HCV prevalences are 4 and 1% respectively [8]. Hepatitis D represents another considerable hepatitis etiology with a prevalence of 5–27% [9].

Hepatitis A and hepatitis E are endemic in the country. The first study reported HEV seroprevalence as 5.9% in 1993 [10]. Limited number of epidemiological studies was published after that preliminary study. In this systematic review, we aimed to analyze HEV studies reported from Turkey, to determine the current situation of the disease in the country, to delineate the limits of the studies and to determine the future study areas.

Methods

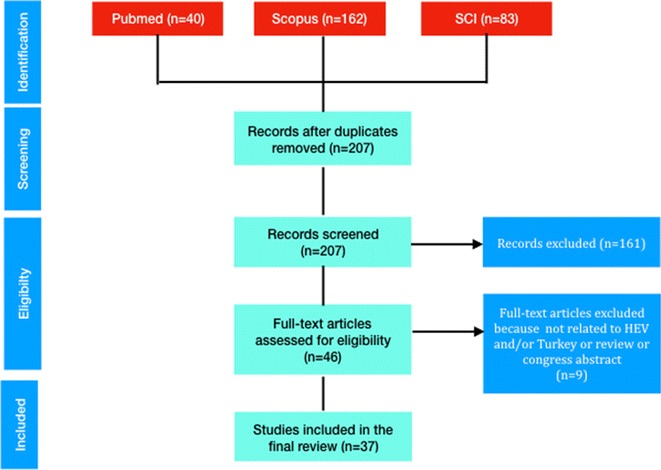

This systematic review was prepared according to the guideline of preparation and report of systematic review (PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [11]. Three main health and biomedical databases of Pubmed, Scopus, and Science Citation Index (SCI) were used for the literature search. Since HEV was discovered in 1983 [1], the search period was taken as 1980 to June 2017.

The search was done using the terms of “Hepatitis E, hepatitis E virus, Turkey, Turkiye, Travel migrant” in the three databases in order to determine all publications about HEV from Turkey. The language was not restricted on the search. Duplicate publications, those not including HEV and/or Turkey, reviews and meeting abstracts were excluded. The result was recorded in Endnote program. Diagrams were produced according to the PRISMA guideline.

Data analysis

Study date, publication date, authors, type of study, study field, sample size, and age groups were identified and presented as tables.

Results

The results of literature search were shown in flow diagram (Fig. 1). A total of 285 publications were identified in the databases; after removing duplicates, the abstracts of remaining 207 publications were further studied. Forty-six publications met the inclusion criteria. Another nine studies were noted not meeting the inclusion criteria after searching full texts and were excluded.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for literature search

Among the remaining studies, one was a case report and another one investigated cupper level in patients with hepatitis including HEV. Twenty-eight publications were the seroprevalence studies in Turkey. Fifteen of these studies were in general population (Table 1), and 13 in specific groups: those with underlying disorders (n = 5), in patients presenting with acute hepatitis (n = 3), in pregnant women (n = 2), in those working in risky occupations (n = 2) and in those residing in the camps (n = 1) (Table 2).

Table 1.

HEV seroprevalence studies in Turkey

| Authors, references | Year published | Year | City | Study type | Sample size | Prevalence (IgG) (%) | Prevalence by age group | Power of study | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aribas et al. [12] | 2000 | NA | Konya | C-S | 162 | 12.3 | NA | Children admitted to hospital | |

| Atabek et al. [13] | 2004 | 2001–2002 | Konya | C-S | 210 | 5.7 | 1–6 year: 0, 7–12 year: 6.8%, 13–18 year: 8.9% | NA | Rural 8.5%, urban 0.2%, p > 0.05 |

| Aydın et al. [14] | 2015 | 2012–2013 | Ankara | C-S | 1043 | 4.4 | 0–18 year: 0, 19–55 year: 30.4%, 56–90 year: 69.5% | NA | |

| Bayhan et al. [15] | 2016 | 2014 | Van | C-S | 408 | 4.2 | 4.4% in 0–5 year, 3.4% in 6–13 year, 5.7% in 14–18 year | Calculated | Individuals admitting to hospital were compared in age groups: no difference. |

| Cesur et al. [16] | 2002 | 2000–2001 | Ankara | C-S | 1046 | 3.8 | 15–30 year: 0, 30–45 year: 4.4%, 45–60 year: 6.6%, > 60 year: 7.4% | NA | 15–75 year age group admitting to hospital |

| Cevahir et al. [17] | 2013 | NA | Denizli | C-S | 185 | 12.4 | 7 year: 18.1%, 14 year: 6.6% | NA | Rural %13.1 vs. urban %11.7, p > 0.05. 7 year had higher prevalence than 6 year group |

| Colak et al. [18] | 2002 | 1996–1997 | Antalya | C-S | 338 | 0.9 | 1–5 year: 0, 6–11 year: 1.6% | NA | No seropositives in preschool children |

| Eker et al. [19] | 2009 | 2005 | Edirne | C-S | 582 | 2.4 | Calculated | No difference in subgroups. Age range was not provided | |

| Kaya et al. [20] | 2008 | 2003 | Düzce | C-S | 589 | 0.3 | 6 month–12 year: 0, 13–17 year: 0.8% | NA | No seropositives in < 13 year-old |

| Maral et al. [21] | 2009 | 2003–2005 | Ankara | L | 515 | 1.7–2.1 | NA | 6–14 year group. Same group re-studied 2 years later | |

| Olcay et al. [22] | 2003 | 2000 | Ankara, Manisa, Diyarbakir | C-S | 910 | 6.3 | 7–14 year: 1.6%, 15–24 year: 3.3%, 25–64 year: 8.2%, > 64 year: 10% | NA | Ankara 2.7%, Manisa 3.8%, Diyarbakir %11.7, significant. In Diyarbakir prevalence increased by age |

| Sidal et al. [23] | 2001 | 1997–1998 | Istanbul | C-S | 909 | 2.1 | 6 month–2 year: 4.8%, 2–5 year: 3.1%, 5–10 year: 2.1%, 10–16 year: 0.3% | NA | |

| Thomas et al. [10] | 1993 | 1990–1992 | Istanbul, Aydin, Ayvalik, Adana, Trabzon | C-S | 1350 | 5.9 | 11–20 year: 0, 21–30 year: 3.7%, 31–40 year: 9.1%, 41–50 year: 5.7%, 51–60 year: 8.7%, 61–70 year: 6.9%, 71–80 year: 11.1% | NA | Older age, HCV, being in Adana city were determined as risk factors |

| Yuce et al. [24] | 1998 | NA | Ankara | C-S | 400 | 0 | 0 month–17 year: 0 | NA |

C-S Cross-sectional, L longitudinal, y years old, m months old, NA not available

Table 2.

HEV seroprevalence in special groups

| Authors, references | Year published | Year | City | Study type | Target population | Sample size | Prevalence | CG sample size | CG prevalence (IgG) (%) | Power of study | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aksu et al. [25] | 1999 | 1996–1998 | İzmir | C-S | Behcet’s disease | 124 | 7% | 51 | 8 | NA | p > 0.05 |

| Atabek et al. [26] | 2003 | NA | Konya | C-S | Diabetic children | 63 | 6.3% | 63 | 7.9 | NA | p > 0.05 |

| Aydin et al. [27] | 2016 | NA | Erzurum | C-S | Animal workers | 103 | 35.9% | 92 | 4.4 | NA | p < 0.05. Most frequent in animal husbandry, poultry. No seropositivity in veterinaries |

| Bayram et al. [28] | 2007 | 2004 | Gaziantep | C-S | Adult CHB and CHC | 364 | CHB: 13.7%, CHC: 54%. HEV RNA (+); CHB: 14.7%, CHC: 54.6% | 178 | 15.7 | NA | HEV higher in CHC patients (p < 0.05), speculated that HCV and HEV may share the same way of transmission |

| Cengiz et al. [29] | 1996 | NA | Samsun | C-S | Adult HD patients | 72 | 13.9% | 55 | 5.5 | NA | p < 0.05 |

| Cevrioglu et al. [30] | 2004 | 2000–2002 | Afyon | C-S | Pregnant women | 245 | 12.6% | 76 | 11.8 | NA | p > 0.05 |

| Ceylan et al. [31] | 2003 | NA | Diyarbakir | C-S | Agricultural workers | 46 | 34.8% | 45 | 4.4 | NA | p < 0.05 |

| Coursaget et al. [32] | 1993 | NA | Istanbul | C-S | Acute non-A non-B non-C hepatitis | 18 | 11% | NA | NA | Probable prevalence 1–2%. Letter to a study | |

| Koksal et al. [33] | 1994 | 1991–1992 | Diyarbakir | C-S | Acute non-A non-B hepatitis | 53 | 73.3% | 100 | 0 | NA | |

| Oncu et al. [34] | 2006 | NA | Aydin | C-S | Pregnant women | 386 | 7% | NA | NA | Low prevalence in high-educated | |

| Sencan et al. [35] | 2004 | 1999 | Duzce | C-S | Children post-earthquake camps | 476 | 4.7–17.2% | NA | NA | Duzce and Golyaka camps have significantly different rates attributed to being the first camp just after the earthquake with lower sanitation status | |

| Uçar et al. [36] | 2009 | NA | Hatay | C-S | Adults HD patients | 92 | 20.6% | NA | NA | ||

| Yayli et al. [37] | 2002 | NA | Isparta | C-S | Children | 340 | 9% | NA | NA | 5–16 age range. After a hepatitis outbreak in the village, some children had symptoms and higher ALT |

CG Control group, C-S cross-sectional, NA not available, CHB chronic hepatitis B, CHC chronic hepatitis C, HD hemodialysis

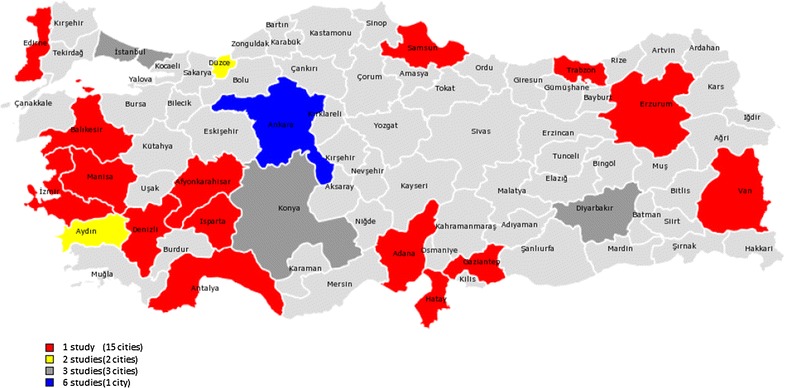

For the remaining six studies, two were seroprevalence studies including Turkish immigrants in Italy and the Netherlands (Table 3), and four were acute HEV infection case reports developing after travel to Turkey. The cities in which the studies were performed are given in Fig. 2.

Table 3.

HEV infection prevalence in migrants

| Authors, reference | Year | Country | Study type | Target population | Sample size | Prevalence (IgG) (%) | Power | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chironna et al. [38] | 2000 | Italy | Cross sectional | Adults | 368 | 10.3 | NA | Immigrants from Turkey. No seropositives in 0–10 year-old group |

| Sadik et al. [39] | 2004 | Netherlands | Cross sectional | Adults | 296 | 33.4 | NA | Seroprevalence is similar to that in Dutch population |

NA not available

Fig. 2.

Distribution of the studies. Colors represent number of studies (total number of sites are more than actual study numbers because some studies were done in more than one city)

Hepatitis E virus seroprevalence ranges from 0 to 12.4% among healthy individuals (Table 1). The prevalence was determined as 7–8% in pregnant women, 13% in chronic HBV patients, 54% in chronic HCV patients, 13.9–20.6% in patients with chronic renal failure, and ≈ 35% in agriculture workers (Table 2).

Among individuals immigrating form Turkey to Europe, HEV seroprevalence was found 10.3% in Italy [38] and 33.4% in the Netherlands (Table 3) [39]. Four patients were reported with a travel history to Turkey [from Germany (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), and UK (n = 2)] and one died of HEV fulminant hepatitis [40–43].

Discussion

No any outbreaks of HEV have been reported from Turkey so far. The seroprevalence of HEV depends on the region, age group, and study population. Using different ELISA kits in the diagnosis may have a role since the sensitivities of the ELISA kits are different [44, 45].

The studies were performed mainly in the big cities of Ankara and Istanbul and the study populations included blood donors and patient admitting to the hospitals with a reason other than hepatitis. For that reason, the studies give a general idea about the seroprevalence and may not provide realistic information. HEV seroprevalence is lower in children than in adults and the children lack antibodies. HEV seroprevalence is low, even zero in some pediatric series although HAV seroprevalence, another fecal–oral transmitted virus is high [10, 14, 18, 20, 22].

Similarly, a systematic review of HEV infection in children reported the seroprevalence as < 10% in children younger than 10-year old [46]. No change was detected in the seroprevalence in these children by time [13]. No any difference was detected in HEV seroprevalence in children living rural or urban areas [13, 17]. These results suggest that fecal route is not a main way of transmission or HEV transmission is low due to low fecal secretion and its low infectivity rate.

Hepatitis E virus seroprevalence increases by age in Turkey. It is higher in 3rd–4th decades and older age was determined as an independent risk factor for HEV seropositivity in a meta-analysis [10]. HEV seroprevalence differ according to the regions; being highest in the Southeastern Anatolia region and lowest in the western parts of the country [22].

Low socio-economical status may be associated with the higher seroprevalence. Seroprevalence is higher than the general population in those staying camps [35], working in agriculture and animal husbandry [31] those with chronic blood-borne infections of HBV and HCV [28], and patients with chronic renal failure given transfusions [29, 36] suggesting that more than one way of transmission may be effective.

Any study about HEV in water sources was not found in the databases. A doctoral thesis reported HEV-RNA positivity by RT-PCR in 3 out of 150 samples (drinking water, well water, swimming pool, sea water, river water, and sewage) from differing parts of the country [47]. This finding suggests a lower rate of transmission through water sources. There is a need for multi-center, well-planned epidemiologic studies searching HEV seroprevalence, ways of transmission, and risk factors in Turkey.

Turkey has been included in the endemic countries for HEV depending on two studies conducted in eastern and western parts of the country 24 years ago and far from reflecting the real situation. The seroprevalence of HEV is not exactly determined although acute hepatitis E is a reportable disease. This may be due to not using the HEV diagnostic tests commonly.

Hepatitis E virus infection may cause fulminant hepatitis and death. Turkey is among the first 10 countries of highest organ transplantation incidence in Europe (39.3 and 16.7/1 million population for kidney and liver respectively) [48]. However HEV prevalence is not known in transplanted patients or in immunosuppressed. Among individuals immigrate from Turkey to Europe; in the Netherlands, HEV seroprevalence was similar to that of the autochthonous Dutch population and another study found higher prevalence in immigrants coming from Turkey. HEV infection may challenge the immunosuppressed and those with underlying disorders especially when they travel to endemic regions. Four patients travelled to Turkey have been reported in the medical literature. Genotype 3 was detected in one case suggesting a food-borne transmission. Current data show that HEV infection related to travel to Turkey is low.

In conclusion; current review gives detailed information about HEV infection in Turkey. Previous studies suggest that Turkey is among the endemic countries of HEV. However, there are some pitfalls for the analysis of data: the studies are not powered enough to represent the whole population; they did not include immunosuppressed patients and solid organ recipients; and the prevalence of non-A non-B hepatitis was not determined. There is a need for well-designed epidemiological studies to determine HEV seroprevalence, ways of transmission, and risk factors.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to this work. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

We declare that the data supporting the conclusions of this article are fully described within the article.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

There is no funding.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- HEV

hepatitis E virus

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- SCI

Science Citation Index

- WHO

World Health Organization

Contributor Information

Hakan Leblebicioglu, Email: hakanomu@yahoo.com.

Resat Ozaras, Email: rozaras@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Balayan MS, Andjaparidze AG, Savinskaya SS, Ketiladze ES, Braginsky DM, Savinov AP, et al. Evidence for a virus in non-A, non-B hepatitis transmitted via the fecal-oral route. Intervirology. 1983;20:23–31. doi: 10.1159/000149370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khuroo MS, Khuroo MS. Hepatitis E: an emerging global disease—from discovery towards control and cure. J Viral Hepat. 2016;23:68–79. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donnelly MC, Scobie L, Crossan CL, Dalton H, Hayes PC, Simpson KJ. Review article: hepatitis E—a concise review of virology, epidemiology, clinical presentation and therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017 doi: 10.1111/apt.14109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartl J, Wehmeyer MH, Pischke S. Acute hepatitis E: two sides of the same coin. Viruses. 2016;8(11). pii=E299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Arends JE, Ghisetti V, Irving W, Dalton HR, Izopet J, Hoepelman AI, et al. Hepatitis E: an emerging infection in high income countries. J Clin Virol. 2014;59:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO . Hepatitis E: fact sheet. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.OECD. OECD economic surveys: Turkey, 2016. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2016. https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-tur-2016-en

- 8.Tozun N, Ozdogan O, Cakaloglu Y, Idilman R, Karasu Z, Akarca U, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infections and risk factors in Turkey: a fieldwork TURHEP study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:1020–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dulger AC, Suvak B, Gonullu H, Gonullu E, Gultepe B, Aydin I, et al. High prevalence of chronic hepatitis D virus infection in Eastern Turkey: urbanization of the disease. Arch Med Sci. 2016;12:415–420. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2015.52030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas DL, Mahley RW, Badur S, Palaoglu KE, Quinn TC. Epidemiology of hepatitis E virus infection in Turkey. Lancet (London, England) 1993;341:1561–1562. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90698-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aribas ET, Altinidis M, Ceri A, Koc H. Hepatitis A and hepatitis E prevalence in children in Konya, Turkey. Arch Gastroenterohepatol. 2000;19:94–96. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atabek ME, Fyndyk D, Gulyuz A, Erkul I. Prevalence of anti-HAV and anti-HEV antibodies in Konya, Turkey. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2004;67:265–269. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(03)00123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aydin NN, Ergünay K, Karagül A, Pinar A, Us D. Investigation of the hepatitis e virus seroprevalence in cases admitted to hacettepe university medical faculty hospital. Mikrobiyoloji bulteni. 2015;49:554–564. doi: 10.5578/mb.9881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bayhan GI, Demioren K, Guducuoglu H. Epidemiology of hepatitis E virus in children in the province of Van, Turkey. Turk Pediatri Arsivi. 2016;51:148–151. doi: 10.5152/TurkPediatriArs.2016.4119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cesur S, Akin K, Doǧaroǧlu I, Birengel S, Balik I. Hepatitis A and hepatitis E seroprevalence in adults in the Ankara area. Mikrobiyoloji bulteni. 2002;36:79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cevahir N, Demir M, Bozkurt AI, Ergin A, Kaleli I. Seroprevalence of hepatitis e virus among primary school children. Pak J Med Sci. 2013;29:629–632. doi: 10.12669/pjms.292.2821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colak D, Ogunc D, Gunseren F, Velipasaoglu S, Aktekin MR, Gultekin M. Seroprevalence of antibodies to hepatitis A and E viruses in pediatric age groups in Turkey. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2002;49:93–97. doi: 10.1556/AMicr.49.2002.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eker A, Tansel O, Kunduracilar H, Tokuç B, Yuluǧkural Z, Yüksel P. Hepatitis e virus epidemiology in adult population in edirne province, Turkey. Mikrobiyoloji bulteni. 2009;43:251–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaya AD, Ozturk CE, Yavuz T, Ozaydin C, Bahcebasi T. Changing patterns of hepatitis A and E sero-prevalences in children after the 1999 earthquakes in Duzce, Turkey. J Paediatr Child Health. 2008;44:205–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maral I, Budakoglu II, Ceyhan MN, Atak A, Bumin MA. Hepatitis E virus seroepidemiology and its change during 1 year in primary school students in Ankara, Turkey. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:831–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olcay D, Eyigün CP, Özgüven ŞV, Avci IY, Beşirbellioǧlu AB, Tosun SY, et al. Anti-HEV antibody prevalence in three distinct regions of Turkey and its relationship with age, gender, education and abortions. Turk J Med Sci. 2003;33:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sidal M, Unuvar E, Oguz F, Cihan C, Onel D, Badur S. Age-specific seroepidemiology of hepatitis A, B, and E infections among children in Istanbul, Turkey. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001;17:141–144. doi: 10.1023/A:1017524630372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuce A, Hascelik G. Absence of antibody to hepatitis E virus in Turkish children. Eur J Pediatr. 1999;158:685–686. doi: 10.1007/PL00008324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aksu K, Kabasakal Y, Sayiner A, Keser G, Oksel F, Bilgic A, et al. Prevalences of hepatitis A, B, C and E viruses in Behcet’s disease. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 1999;38:1279–1281. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.12.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atabek ME, Kart H, Erkul I. Prevalence of hepatitis A, B, C and E virus in adolescents with type-1 diabetes mellitus. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2003;15:133–137. doi: 10.1515/IJAMH.2003.15.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aydin H, Uyanik MH, Karamese M, Timurkan MO. Seroprevalence of hepatitis e virus in animal workers in nonporcine consumption region of Turkey. Future Virol. 2016;11:691–697. doi: 10.2217/fvl-2016-0075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bayram A, Eksi F, Mehli M, Sözen E. Prevalence of hepatitis E virus antibodies in patients with chronic hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis C. Intervirology. 2007;50:281–286. doi: 10.1159/000103916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cengiz K, Ozyilkan E, Cosar AM, Gunaydin M. Seroprevalence of hepatitis E in hemodialysis patients in Turkey. Nephron. 1996;74:730. doi: 10.1159/000189490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cevrioglu AS, Altindis M, Tanir HM, Aksoy F. Investigation of the incidence of hepatitis E virus among pregnant women in Turkey. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004;30:48–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1341-8076.2004.00155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ceylan A, Ertem M, Ilcin E, Ozekinci T. A special risk group for hepatitis E infection: Turkish agricultural workers who use untreated waste water for irrigation. Epidemiol Infect. 2003;131:753–756. doi: 10.1017/S0950268803008719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coursaget P, Depril N, Yenen OS, Cavuslu S, Badur S. Hepatitis E virus infection in Turkey. Lancet (London, England) 1993;342:810–811. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91578-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koksal I, Aydin K, Kardes B, Turgut H, Murt F. The role of hepatitis E virus in acute sporadic non-A, non-B hepatitis. Infection. 1994;22:407–410. doi: 10.1007/BF01715498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oncu S, Oncu S, Okyay P, Ertug S, Sakarya S. Prevalence and risk factors for HEV infection in pregnant women. Med Sci Monit. 2006;12:36–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sencan I, Sahin I, Kaya D, Oksuz S, Yildirim M. Assessment of HAV and HEV seroprevalence in children living in post-earthquake camps from Duzce, Turkey. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19:461–465. doi: 10.1023/B:EJEP.0000027357.57403.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uçar E, Çetin M, Kuvandik C, Helvaci MR, Güllü M, Hüzmeli C. Hepatitis e virus seropositivity in hemodialysis patients in hatay province, Turkey. Mikrobiyoloji bulteni. 2009;43:299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yayli G, Kilic S, Ormeci AR. Hepatitis agents with enteric transmission—an epidemiological analysis. Infection. 2002;30:334–337. doi: 10.1007/s15010-002-2123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chironna M, Germinario C, Lopalco PL, Carrozzini F, Barbuti S, Quarto M. Prevalence rates of viral hepatitis infections in refugee Kurds from Iraq and Turkey. Infection. 2003;31:70–74. doi: 10.1007/s15010-002-3100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sadik S, van Rijckevorsel GGC, van Rooijen MS, Sonder GJB, Bruisten SM. Seroprevalence of hepatitis E virus differs in Dutch and first generation migrant populations in Amsterdam, the Netherlands: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):659. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-2007-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hartmann WJ, Frosner GG, Eichenlaub D. Transmission of hepatitis E in Germany. Infection. 1998;26:409. doi: 10.1007/BF02770849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johansson PJ, Mushahwar IK, Norkrans G, Weiland O, Nordenfelt E. Hepatitis E virus infections in patients with acute hepatitis non-A-D in Sweden. Scand J Infect Dis. 1995;27:543–546. doi: 10.3109/00365549509047064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leighton SP, Gordon C, Shand A. Clopidogrel, Turkey and a red herring? BMJ Case Rep. 2011 doi: 10.1136/bcr.01.2011.3776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramalingam S, Smith D, Wellington L, Vanek J, Simmonds P, MacGilchrist A, et al. Autochthonous hepatitis E in Scotland. J Clin Virol. 2013;58:619–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aggarwal R. Diagnosis of hepatitis E. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:24–33. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wenzel JJ, Preiss J, Schemmerer M, Huber B, Jilg W. Test performance characteristics of Anti-HEV IgG assays strongly influence hepatitis E seroprevalence estimates. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:497–500. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verghese VP, Robinson JL. A systematic review of hepatitis E virus infection in children. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:689–697. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ergin S. Turkiye’nin degisik bolgelerinden toplana su orneklerinde Hepatit E virusu RNA’sinin arastirilmasi [Doctorate]. Istanbul, Turkey: Istanbul University; 1998.

- 48.European Commission Fifth Journalist Workshop 2014. Organ Donation and Transplantation, Brussels, 26 November 2014. https://ec.europa.eu/health/blood_tissues_organs/events/journalist_workshops_organ_en. Accessed 27 Apr 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

We declare that the data supporting the conclusions of this article are fully described within the article.