Abstract

Background

CXCL5 is a member of the CXC-type chemokine family, which has been found to play important roles in tumorigenesis and cancer progression. Recent studies have demonstrated that CXCL5 could serve as a potential prognostic biomarker for cancer patients. However, the prognostic value of CXCL5 is still controversial.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed, Embase and Web of Science to obtain all relevant articles investigating the prognostic significance of CXCL5 expression in cancer patients. Hazards ratios (HR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were pooled to estimate the association between CXCL5 expression levels with survival of cancer patients.

Results

A total of 15 eligible studies including 19 cohorts and 5070 patients were enrolled in the current meta-analysis. Our results demonstrated that elevated expression level of CXCL5 was significantly associated with poor overall survival (OS) (pooled HR 1.70; 95% CI 1.36–2.12), progression-free survival (pooled HR 1.65; 95% CI 1.09–2.49) and recurrence-free survival (pooled HR 1.49; 95% CI 1.15–1.93) in cancer patients. However, high or low expression of CXCL5 made no difference in predicting the disease-free survival (pooled HR 0.63; 95% CI 0.11–3.49) of cancer patients. Furthermore, we found that high CXCL5 expression was associated with reduced OS in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (HR 1.91; 95% CI 1.31–2.78) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HR 1.87; 95% CI 1.55–2.27). However, there was no significant association between expression level of CXCL5 with the OS in lung cancer (HR 1.25; 95% CI 0.79–1.99) and colorectal cancer (HR 1.16; 95% CI 0.32–4.22, p = 0.826) in current meta-analysis.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our meta-analysis suggested that elevated CXCL5 expression might be an adverse prognostic marker for cancer patients, which could help the clinical decision making process.

Keywords: Chemokine, CXCL5, Cancer, Prognosis, Meta-analysis

Background

Despite great improvements in early detection, surgical techniques, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, biological treatment and multidisciplinary treatment in recent years, cancer is still a major public health problem globally, which is associated with high morbidity, mortality and economic burden [1]. It is estimated that 1,735,350 new cancer cases and 609,640 cancer deaths are projected to occur in the United States in 2018 [2]. Given the poor prognosis of cancer patients, numerous investigators have focused on searching for biomarkers that could predict prognosis of cancer. However, sensitivity and specificity of most cancer biomarkers widely used now are not yet satisfactory [3]. Therefore, it is desperately needed to identify novel applicable prognostic biomarkers, not only improving poor prognosis but also providing novel therapeutic targets.

Chemokines are chemotactic cytokines that could regulate the migration of immune cells into damaged or diseased organs in response to pro-inflammatory stimuli [4]. According to cysteine residues in the NH2-terminal part of the protein, chemokines can be classified into four highly conserved groups, namely C, CC, CXC, and CX3C [5]. Chemokines and their receptors could bring about the transcription of target genes involved in cell invasion, motility, survival and interactions with the extracellular matrix, which can induce migration, chemotaxis and rearrangement of the cytoskeleton in the target cell, and therefore promote multiple physiological functions of cells, including cell growth, development, differentiation and apoptosis [6–9]. Over the past few years, accumulating evidence has revealed that chemokines play pivotal roles in progression of tumor [10]. Chemokines produced by tumor and stromal cells can induce the expression and distribution of tumor-associated leukocytes, trigger angiogenesis, contribute to the growth and metastasis of malignant cells and generate fiber keratinocytes [6, 11, 12]. In addition, chemokines and their receptors are critical mediators of inflammation microenvironment of cancer, which has been proposed to represent the seventh hallmark of cancer [13, 14]. Given the important roles of chemokines in cancer, abnormal expression of chemokines has been detected in many tumors, and several chemokines have been proven to be associated with poor prognosis of cancer patients [15–17].

CXCL5, also known as epithelial-derived neutrophil-activating peptide 78 (ENA78), is originally discovered as a potent chemoattractant and activator of neutrophil function. Through binding to its receptor CXCR2, CXCL5 could induce the chemotaxis of neutrophils, promote angiogenesis, and remodel connective tissue [18]. Accumulating evidence suggests that CXCL5 may participate in cancer-related inflammation, which is involved in many aspects of malignancy in cancer biology [19]. Furthermore, abnormal expression of CXCL5 has been identified in many tumors. CXCL5 is overexpressed in gastric cancer, prostate cancer, endometrial cancer, squamous cell cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma and pancreatic cancer, and increased expression of CXCL5 is associated with advanced tumor stages, local invasion, neutrophil infiltration and metastatic potential [20–25]. Recent studies have revealed that CXCL5 could serve as a potential prognostic biomarker for patients with cancer [5, 19, 26, 27]. However, its prognostic value is still controversial owing to the fact that most studies reported so far are limited in discrete outcome and sample size. Therefore, we performed the current quantitative meta-analysis to elucidate the prognostic significance of CXCL5 expression in cancer patients.

Materials and methods

Study strategy

The present review was performed in accordance with the standard guidelines for meta-analysis and systematic reviews of tumor marker prognostic studies [28, 29]. The database Web of Science, PubMed and Embase were independently searched by two researchers (Binwu Hu and Huiqian Fan) to obtain all relevant articles about the prognostic value of CXCL5 in patients with any tumor. The literature search ended on March 1, 2018. The search strategy used both MeSH terminology and free-text words to increase the sensitivity of the search. The search strategy was: “CXCL5 or CXC chemokine ligand 5 or ENA78 or epithelial cell derived neutrophil attractant 78” AND “cancer or tumor or carcinoma or neoplasm or malignancy” AND “prognostic or prognosis or survival or outcome”. We also screened the references of retrieved relevant articles to identify potentially eligible literatures. Conflicts were solved through group discussion.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies included in this analysis had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) patients were pathologically diagnosed with any type of human cancer. (2) CXCL5 expression levels were determined in human tissues or plasma samples. (3) Patients were divided into two groups according to the expression levels of CXCL5, the relationship between CXCL5 expression levels with survival outcome was investigated. (4) Sufficient published data or the survival curve were provided to calculate hazard ratios (HR) for survival rates and their 95% confidence intervals (CI). Exclusion criteria were as follow: studies using non-human samples, studies without usable or sufficient data, laboratory articles, reviews, letters, case reports, non-English or unpublished articles and conference abstracts. All eligible studies were carefully screened by two researchers (Binwu Hu and Huiqian Fan), and discrepancies were resolved by discussing with a third researcher (Xiao Lv).

Data extraction

Two investigators (Binwu Hu and Huiqian Fan) extracted relevant data independently and reached a consensus on all items. For all eligible studies, the following information of each article was collected: author, year of publication, tumor type, samples detected, expression associated with poor prognosis, Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) score, method of obtaining HRs, characteristics of the study population (including country of the population enrolled, number of patients (high/low), follow up (month)), endpoints, assay method, cut-off value and survival analysis. For endpoints, overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS), progression-free survival (PFS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) were all regarded as endpoints. We employed HR which was extracted following a methodology suggested previously to evaluate the influence of CXCL5 expression on prognosis of patients [30]. If possible, we also asked for original data directly from the authors of the relevant studies.

Quality assessment

Quality of all included studies was assessed independently by two researchers (Binwu Hu and Huiqian Fan) using the validated Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, and disagreements were resolved through discussion with another researcher (Songfeng Chen). This scale uses a star system to evaluate a study in three domains: selection of participants, comparability of study groups, and the ascertainment of outcomes of interest. We considered studies with scores more than 6 as high-quality studies, and those with scores no more than 6 as low-quality studies.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata Software 14.0 (Stata, College Station, TX). Pooled HRs (high/low) and their associated 95% CIs were used to analyze the prognostic role of CXCL5 expression in various cancers. The heterogeneity among studies was evaluated using Cochran’s Q and I2 statistics. A p value less than 0.10 or an I2 value larger than 50% were considered statistically significant. The fixed-effect model was used for analysis without significant heterogeneity between studies (p > 0.10, I2 < 50%). Otherwise, the random-effect model was chosen. To explore the source of heterogeneity, subgroup analysis and meta-regression were preformed through classifying the included studies into subgroups according to similar features. We also conducted sensitivity analysis to test the effect of each study on the overall pooled results. The publication bias was evaluated by using both Begg’s test and Egger’s test. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of studies

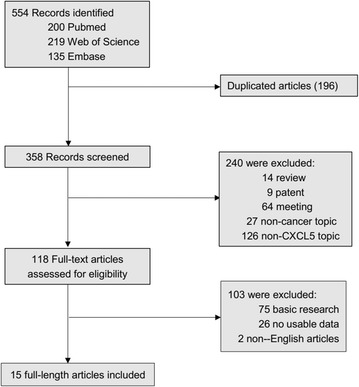

According to our search strategy, the initial search algorithm retrieved a total of 554 studies. The following studies were excluded: duplicates (n = 196), review (n = 14), patent (n = 9), meeting abstract (n = 64), studies describing non-cancer topics (n = 27), studies describing non-CXCL5 topics (n = 126), studies belonging to basic research (n = 75), studies lacking relevant data (n = 26) and non-English articles (n = 2). Eventually, 15 studies meeting the inclusion criteria were included in this meta-analysis. The screening process and results are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The flow diagram indicated the process of study selection

The main characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. A total of 15 studies including 19 cohorts were included in the current meta-analysis. Among these studies, a total of 5070 patients were included, with a minimum sample size of 27 and a maximum sample size of 2437 patients. The accrual period of these studies ranged from 2007 to 2018. The follow-up time ranged from 23 months to 180 months. Ten different types of cancer were involved in the enrolled studies including intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (n = 2) [27, 31], lung cancer (n = 3) [26, 32, 33], colorectal cancer (n = 3) [34–36], biliary tract cancer (n = 1) [10], breast cancer (n = 1) [5], bladder cancer (n = 1) [19], glioma (n = 1) [18], pancreatic cancer (n = 1) [25], hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 1) [24] and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (n = 1) [37]. Among these studies, OS (n = 14), DFS (n = 3), PFS (n = 3) and RFS (n = 3) were estimated as survival outcome. The CXCL5 expression levels in these studies were mostly measured by using immunohistochemistry (IHC) technique, while real time PCR (RT-PCR) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) were also applied. Because the cut-off definitions were various, the cut-off values were different in these studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Author | Year | Region | Type of cancer | Sample size (high/low) | Follow-up (month) | Endpoints | Expression associated with poor prognosis | Samples detected | Assay method | Cut-off value | Survival analysis | NOS score | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al. | 2018 | Korea | Biliary tract cancer | 4/23 | 23 | OS | High | Blood | ELISA | High: serum CXCL5 levels were > 2.081 ng/mL | Multivariate | 7 | 1 |

| Bièche et al. | 2007 | France | Breast cancer | 24/24 | 120 | RFS | High | Tissue | RT-PCR | ROC | Univariate | 7 | 2 |

| Oksana et al. | 2014 | Poland | Lung cancer | 37/37 | 82 | OS, DFS | Low | Tissue | RT-PCR | High: the gene expression of CXCL5 in tumor tissue was more than 1.08 times than normal tissue | Multivariate | 7 | 2 |

| Zhou et al. | 2014 | China | Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | 70/70 | 120 | OS | High | Tissue | IHC | Median | Univariate Multivariate | 7 | 1 |

| Zhu et al. | 2016 | China | Bladder cancer | 131/124 | 87 | OS, RFS, PFS | High | Tissue | IHC | High: IRS > 4 | NA | 7 | 2 |

| Dai et al. | 2016 | China | Glioma | 34/31 | 48 | OS | High | Tissue | WB, RT-PCR | Median | NA | 6 | 2 |

| Wu et al. | 2017 | China | Lung cancer | 75 | 60 | OS | High | Tissue | IHC,RT-PCR | High: the multiplication for intensity and proportion was more than 2 | Univariate Multivariate | 7 | 2 |

| 2437 | 60 | OS, PFS | High | Tissue | RT-PCR | Median | Univariate | 6 | 1 | ||||

| Kawamura et al. | 2011 | Japan | Colorectal cancer | 69/181 | 104 | OS | High | Blood | ELISA | High: serum CXCL5 levels were > 1.53 ng/mL | Univariate Multivariate | 7 | 1 |

| Han et al. | 2015 | China | Lung adenocarcinoma | 34/192 | 127 | OS,RFS | High | Tissue | RT-PCR | Median | Univariate | 6 | 2 |

| Speetjens et al. | 2008 | The Netherlands | Colorectal cancer | Cohort 1 53/17 | 172 | DFS | Low | Tissue | RT-PCR | The 25th percentile as cut off point | Univariate Multivariate | 7 | 1 |

| Cohort 2 50/8 | 162 | OS | Low | Tissue | IHC | High: CXCL5 expression in > 50% of the tumor cells | Univariate Multivariate | 7 | 1 | ||||

| Okabe et al. | 2012 | Japan | Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | 25/25 | 126.3 | OS | High | Tissue | IHC | High: a percentage of the total number of stained cells > 10% | NA | 6 | 2 |

| Li et al. | 2010 | USA | Pancreatic cancer | 130/23 | 180 | OS | High | Tissue | IHC | High: percentage of tumor cells staining positively for CXCL5 > 5.5% | NA | 6 | 2 |

| Zhou et al. | 2012 | China | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 47/47 | 50 | OS | High | Tissue | IHC | Median | Univariate Multivariate | 8 | 1 |

| 162/161 | 75 | OS | High | Tissue | IHC | Median | Univariate Multivariate | 8 | 1 | ||||

| 251/251 | 75 | OS | High | Tissue | IHC | Median | Univariate Multivariate | 8 | 1 | ||||

| Zhang et al. | 2013 | China | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | 75/70 | 105 | OS, PFS | High | ELISA | High: serum CXCL5 levels were > 0.805 ng/ml | Univariate Multivariate | 7 | 1 | |

| Zhao et al. | 2017 | China | Colorectal cancer | 48/30 | 60 | OS, DFS | High | IHC | High: a staining score of 4.5 as the cut-off value | Univariate Multivariate | 8 | 1 |

Method: 1 denoted as obtaining HRs directly from publications; 2 denoted as HRs calculated from the total number of events, corresponding p value and data from Kaplan–Meier curves

OS overall survival, DFS disease-free survival, PFS progression-free survival, RFS recurrence-free survival, IHC immunohistochemistry, RT-PCR real time polymerase chain reaction, ELISA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, NA not available, ROC receiver operating characteristics, NOS Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

Association between CXCL5 expression levels with OS of cancer patients

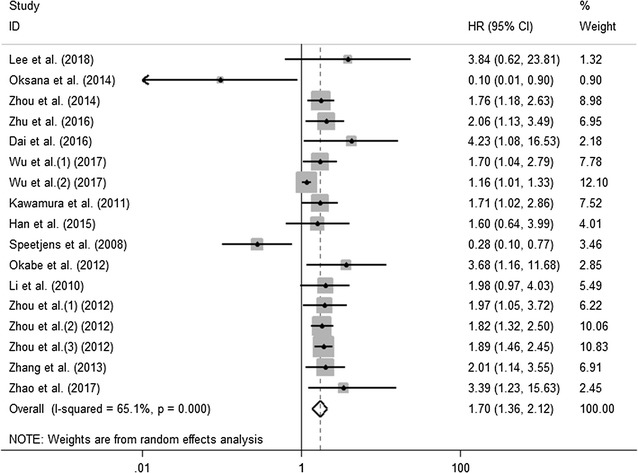

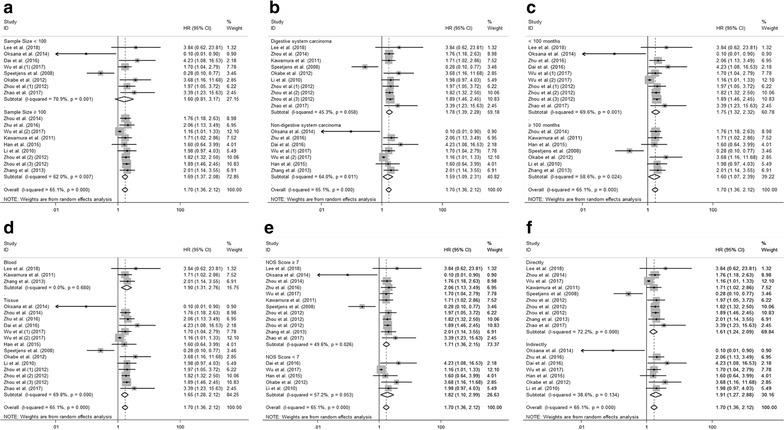

Fourteen studies including seventeen cohorts reported the relationship between abnormal expression levels of CXCL5 with OS in a total of 4952 cancer patients. We used random-effect model to calculate the pooled HR. The pooled HR for OS was 1.70 (95% CI 1.36–2.12, p < 0.001), which suggested that elevated expression level of CXCL5 was significantly associated with poor OS in cancer patients (Fig. 2). Given that significant heterogeneity existed among studies (I2 = 65.1%; p < 0.001), we further conducted subgroup analysis by factors of sample size (fewer than 100 or more than 100), type of cancer (digestive system or non-digestive system carcinoma), follow-up time (fewer than 100 or more than 100 months), samples detected (blood or tissue), paper quality (NOS scores ≥ 7 or < 7) and source of HR (directly or indirectly) to explore the source of heterogeneity (Fig. 3a–f). The results of subgroup analysis illustrated that the association between increased expression level of CXCL5 with poor OS of cancer patients was still significant in all factors above except for the subgroup of studies with fewer than 100 patients (HR 1.60, 95% CI 0.81–3.17, p = 0.175) (Table 2). To further explore the sources of heterogeneity, we performed meta-regression by the covariates including above factors. However, meta-regression didn’t reveal p values less than 0.05 in above covariates, which indicated that all above factors were not the sources of heterogeneity (Table 2). Furthermore, using Cox multivariate analysis in eight studies including ten cohorts, we found that elevated CXCL5 expression levels was an independent prognostic factor for OS in cancer patients (HR 1.65, 95% CI 1.24–2.20, p = 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis of the pooled HRs of OS for cancer patients

Fig. 3.

Results of subgroup analysis of pooled HRs of OS for cancer patients. a Subgroup analysis stratified by sample size. b Subgroup analysis stratified by type of cancer. c Subgroup analysis stratified by follow-up time. d Subgroup analysis stratified by sample detected. e Subgroup analysis stratified by NOS score. f Subgroup analysis stratified by source of HR

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis of pooled HRs for OS in cancer patients with abnormal expression level of CXCL5

| Subgroup analysis | No. of cohorts | Pooled HRs | Meta regression (p value) | Heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random | I2 (%) | p value | |||

| Sample size | 0.602 | ||||

| < 100 | 8 | 1.60 [0.81–3.17] | – | 70.9 | 0.001 |

| ≥ 100 | 9 | 1.69 [1.37–2.08] | – | 62.0 | 0.007 |

| Type of cancer | 0.197 | ||||

| Digestive system carcinoma | 10 | 1.78 [1.39–2.28] | – | 45.3 | 0.058 |

| Non-digestive system carcinoma | 7 | 1.59 [1.09–2.31] | – | 64.0 | 0.011 |

| Follow-up time | 0.204 | ||||

| < 100 | 10 | 1.75 [1.32–2.32] | – | 69.6 | 0.001 |

| ≥ 100 | 7 | 1.60 [1.07–2.39] | – | 58.6 | 0.024 |

| Samples detected | 0.186 | ||||

| Blood | 3 | 1.90 [1.31–2.76] | – | 0.0 | 0.680 |

| Tissue | 14 | 1.65 [1.28–2.12] | – | 69.8 | 0.000 |

| NOS score | 0.526 | ||||

| ≥ 7 | 12 | 1.71 [1.36–2.15] | – | 49.6 | 0.026 |

| < 7 | 5 | 1.82 [1.10–2.99] | – | 57.2 | 0.053 |

| Source of HR | 0.209 | ||||

| Directly | 10 | 1.61 [1.24–2.09] | – | 72.2 | 0.000 |

| Indirectly | 7 | 1.91 [1.27–2.88] | – | 38.6 | 0.134 |

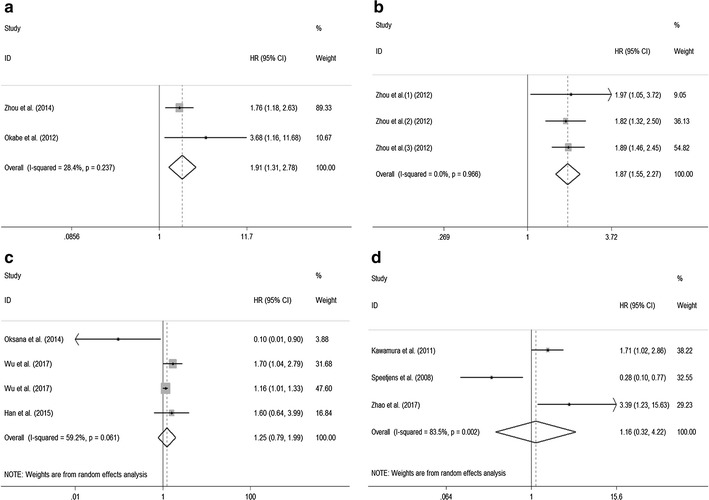

Association between CXCL5 expression levels with OS of certain types of cancer

We further evaluated the prognostic value of CXCL5 in certain types of cancer. Through systematic analysis, our results demonstrated that high CXCL5 expression was associated with reduced OS in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (HR 1.91; 95% CI 1.31–2.78, p = 0.001) (Fig. 4a) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HR 1.87; 95% CI 1.55–2.27, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4b). However, there was no significant association between expression level of CXCL5 with OS of cancer patients in lung cancer (HR 1.25; 95% CI 0.79–1.99, p = 0.335) (Fig. 4c) and colorectal cancer (HR 1.16; 95% CI 0.32–4.22, p = 0.826) (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4.

Meta-analysis of the pooled HRs of OS for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (a), hepatocellular carcinoma (b), lung cancer (c), and colorectal cancer (d)

Association between CXCL5 expression levels with DFS, PFS and RFS of cancer patients

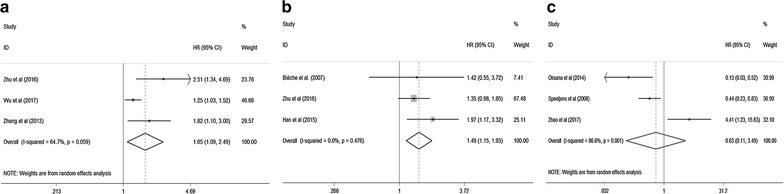

There were three studies respectively evaluating the relationship between CXCL5 expression levels with DFS, PFS and RFS. Through systematic analysis, our results revealed that higher expression level of CXCL5 was significantly associated with shorter PFS (HR 1.65; 95% CI 1.09–2.49, p = 0.018) (Fig. 5a) and RFS (HR 1.49; 95% CI 1.15–1.93, p = 0.003) (Fig. 5b). However, high or low expression of CXCL5 made no difference in predicting the DFS (HR 0.63; 95% CI 0.11–3.49, p = 0.595) (Fig. 5c). In addition, due to the limited number of included studies, we did not perform the subgroup analysis.

Fig. 5.

Meta-analysis of the pooled HRs of PFS (a), RFS (b) and DFS (c) for cancer patients

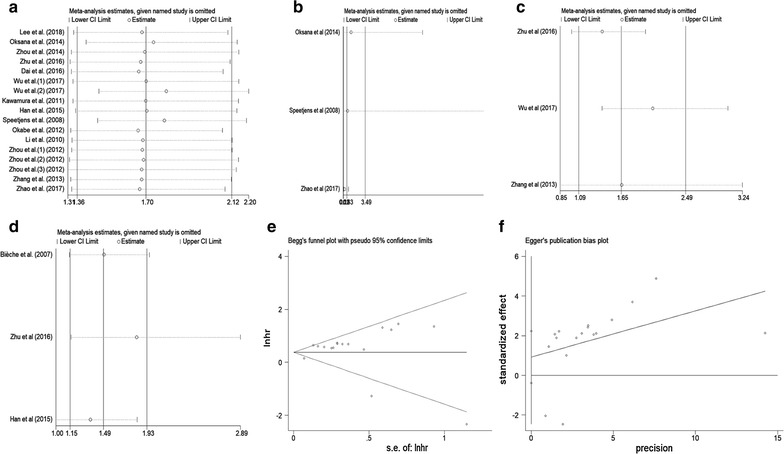

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

We performed sensitivity analysis to examine the effects of individual study on the overall results. For OS, the sensitivity analysis identified that results from Wu et al. (2) and Speetjens et al. affected results greatly, which indicated that these two studies were possible to be the main source of heterogeneity. However, the list of pooled HRs and 95% CIs after excluding single study one by one indicated robustness of our results, in which all pooled HRs and 95% CIs were above the null hypothesis of 1 (Fig. 6a). For DFS (Fig. 6b) and PFS (Fig. 6c), the sensitivity analysis revealed that all included studies affected results greatly. For RFS, only the results from Bièche et al. did not influence the results greatly (Fig. 6d). The sensitivity analysis results demonstrated that our results for DFS, PFS and RFS were not that stable, which might be because of the limited number of studies included in each analysis. Therefore, more relevant studies are warranted to investigate the effects of CXCL5 on DFS, PFS and RFS in human cancer.

Fig. 6.

Sensitivity analysis plot of pooled HRs of OS (a), DFS (b), PFS (c) and RFS (d) for cancer patients with abnormally expressed CXCL5. Begg’s test (e) and Egger’s test (f) for publication bias

Begg’s test and Egger’s linear regression test were conducted to evaluate publication bias. For OS, Begg’s test (p = 0.773) (Fig. 6e) and Egger’s test (p = 0.157) (Fig. 6f) showed no significant publication bias across studies. For DFS, PFS and RFS, because of the limited number of studies (below 10) included in each analysis, publication bias was not assessed.

Discussion

CXCL5 is originally discovered as a potent chemoattractant and activator of neutrophil function [33]. Through interacting with CXCR2 receptor, it could function both as a chemoattractant and as an angiogenic factor [35, 38, 39]. Recently, CXCL5 has been shown to be able to promote the proliferation, migration and invasion of various tumor cells and play pivotal roles in the pathogenesis and progression of cancer [27, 37]. It was reported that CXCL5 protein was higher in various lung cancer tissues, which was positively associated with tumor stage, lymph node metastasis, and worse survival [26] [19, 40]. Zhou et al. also reported that CXCL5 was overexpressed in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma cell lines and tumor samples, which could promote intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma growth and metastasis by recruiting intratumoral neutrophils [27]. Furthermore, CXCL5 could directly induce endothelial cell proliferation and invasion in vitro and promote tumor angiogenesis in non-small cell lung carcinoma and pancreatic cancer [41–43]. Considering the important functions of CXCL5 in cancer, studies have demonstrated that CXCL5 could serve as a potential prognostic biomarker for cancer patients. However, the prognostic value of CXCL5 is still controversial. Because even in the same type of tumor, there are almost opposite conclusions about the prognostic value of CXCL5 [34–36].

Here we performed the current comprehensive meta-analysis to systematically explore the prognostic value of abnormally expressed CXCL5 in cancer patients. We examined 15 independent studies including 19 cohorts and 5070 patients. Through systematic analysis, our results demonstrated that high expression level of CXCL5 was significantly associated with poor OS in cancer patients. Due to the significant heterogeneity across these studies, we performed subgroup analysis and meta-regression analysis to explore the sources of heterogeneity. The results of subgroup analysis suggested that sample size (fewer than 100 or more than 100) altered the significance of prognostic role of CXCL5 in OS (HR 1.60, 95% CI 0.81–3.17 vs HR 1.69, 95% CI 1.37–2.08). This indicated that difference in sample size might be the source of heterogeneity. However, meta-regression analysis failed to identify the source of the significant heterogeneity in above covariates. In addition, by combining HRs from Cox multivariate analysis, we found that CXCL5 was an independent prognostic factor of OS in cancer patients.

Furthermore, we evaluated the prognostic value of CXCL5 in certain types of cancer. We found that high CXCL5 expression was associated with reduced OS in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma, which was consistent with previous studies. However, there was no significant association between expression level of CXCL5 with the OS of lung cancer and colorectal cancer. For lung cancer, results from Oksana et al. were contrary to others greatly [32]. The reason might be that they only evaluated the prognostic value of CXCL5 in early stage non-small cell lung cancer (stages I and II) [32]. Similarly, for colorectal cancer, the results from Speetjens et al. also conflicted with others because they did not include stage IV patients [35, 36]. Therefore, we may speculate that CXCL5 might have different prognostic roles in different tumor stage and larger-scale, multicenter studies including all stage patients are needed to verify our hypothesis.

DFS, PFS and RFS are all important parameters reflecting the progression of tumor. Our results demonstrated that higher expression level of CXCL5 was significantly associated with shorter PFS and RFS in cancer patients. However, high or low expression of CXCL5 made no difference in predicting the DFS of cancer patients. In addition, because only three studies respectively were included to evaluate the association between CXCL5 expression levels with DFS, PFS and RFS, more studies are necessary to explore the relationship between CXCL5 with tumor progression.

Mechanisms underlying the regulatory role of CXCL5 in tumorigenesis and tumor progression have been extensively investigated. CXCL5 could activate multiple signaling pathways to promote the progression of cancer. Dai et al. found that overexpression of CXCL5 markedly upregulated the activity of the JNK, ERK and p38 MAPK signaling pathways, which may contribute to the promoting effects of CXCL5 on the proliferation and migration of glioma cells [18]. In bladder cancer, CXCL5 was found to be significantly upregulated and the CXCL5/CXCR2 axis could promote the migration and invasion of bladder cancer cells by activating the PI3K/AKT-induced upregulation of MMP2/MMP9 [19, 40]. The CXCR2/CXCL5 axis was also found to enhance epithelial-mesenchymal transition of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through the activation of the PI3K/AKT/GSK-3β/Snail signaling [44]. Furthermore, Hsu et al. demonstrated that progression of breast cancer induced by TAOB-derived CXCL5 was associated with increased Raf/MEK/ERK activation and mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1 (MSK1) and Elk-1 phosphorylation, as well as Snail upregulation [44]. In addition, CXCL5 was shown to have potent effects on neutrophil recruitment in cancer [45, 46]. Meanwhile, neutrophils could potentiate cancer cell migration, invasion and dissemination by secreting immunoreactive molecules such as hepatocyte growth factor, oncostatin M, b2-integrins or neutrophil elastase, which might be another mechanism for CXCL5 promoting cancer progression [27, 47, 48]. What’s more, it has been reported that stem cells could produce CXCL5, and Zhao et al. demonstrated that CXCL5 secreted by adipose tissue-derived stem cells could promote breast tumor cell proliferation [49]. Thus, we could speculate that CXCL5 might be the indicator of the presence of putative cancer stem cells, which have been shown to be associated with the metastasis and poor prognosis of cancer patients [50, 51].

However, the current meta-analysis had some limitations. First, the cut-off value of high and low CXCL5 expression was different among studies, which might lead to the bias of the results. Second, some HRs could not be directly obtained from the publications. Thus, calculating them through survival curves might not be precise enough. Third, differences of paper quality and sample size across the studies might cause bias in the meta-analysis, although meta-regression did not show the paper quality or sample size as the resource of heterogeneity. Therefore, larger-scale, multicenter, and high-quality studies are desperately necessary to confirm our findings.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study revealed that elevated expression level of CXCL5 might be an adverse prognostic marker for OS, PFS and RFS in cancer patients. However, no significant association was found between CXCL5 expression level with DFS in the current meta-analysis. In a word, this is the first meta-analysis to evaluate the relationship between expression levels of CXCL5 with prognosis of cancer patients. In the future, more relevant studies are warranted to investigate the role of CXCL5 in human cancer.

Authors’ contributions

BH, HF and XL collected, extracted and analyzed the data, wrote the paper; XL and SC performed quality assessment and analyzed the data. ZS conceived and designed this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the researchers and study participants for their contributions.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by Grants 2016YFC1100100 from The National Key Research and Development Program of China, Grants 91649204 from Major Research Plan of National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence intervals

- HR

hazard ratios

- OS

overall survival

- DFS

disease-free survival

- PFS

progression-free survival

- RFS

recurrence-free survival

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- RT-PCR

real time polymerase chain reaction

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Footnotes

Binwu Hu and Huiqian Fan contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Binwu Hu, Email: hubinwu@hust.edu.cn.

Huiqian Fan, Email: fanhuiqianuh@163.com.

Xiao Lv, Email: xlyu2@jhmi.edu.

Songfeng Chen, Email: chensongfeng123@126.com.

Zengwu Shao, Phone: 86-027-85805503, Email: szwpro@163.com.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi D, Wu F, Gao F, Qing X, Shao Z. Prognostic value of long non-coding RNA CCAT1 expression in patients with cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(6):e0179346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehling J, Tacke F. Role of chemokine pathways in hepatobiliary cancer. Cancer Lett. 2016;379(2):173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bieche I, Chavey C, Andrieu C, Busson M, Vacher S, Le Corre L, Guinebretiere J-M, Burlinchon S, Lidereau R, Lazennec G. CXC chemokines located in the 4q21 region are up-regulated in breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2007;14(4):1039–1052. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balkwill F. Cancer and the chemokine network. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(7):540–550. doi: 10.1038/nrc1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen SJ, Crown SE, Handel TM. Chemokine: receptor structure, interactions, and antagonism. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:787–820. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mellado M, Rodriguez-Frade JM, Manes S, Martinez AC. Chemokine signaling and functional responses: the role of receptor dimerization and TK pathway activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:397–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sallusto F, Mackay CR, Lanzavecchia A. The role of chemokine receptors in primary, effector, and memory immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:593–620. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SJ, Kim JE, Kim ST, Lee J, Park SH, Park JO, Kang WK, Park YS, Lim HY. The correlation between serum chemokines and clinical outcome in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer. Transl Oncol. 2018;11(2):353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mantovani A, Savino B, Locati M, Zammataro L, Allavena P, Bonecchi R. The chemokine system in cancer biology and therapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21(1):27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allavena P, Germano G, Marchesi F, Mantovani A. Chemokines in cancer related inflammation. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317(5):664–673. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mantovani A. Cancer: inflaming metastasis. Nature. 2009;457(7225):36–37. doi: 10.1038/457036b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazennec G, Richmond A. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: new insights into cancer-related inflammation. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16(3):133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samarendra H, Jones K, Petrinic T, Silva MA, Reddy S, Soonawalla Z, Gordon-Weeks A. A meta-analysis of CXCL12 expression for cancer prognosis. Br J Cancer. 2017;117(1):124–135. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghoneim HM, Maher S, Abdel-Aty A, Saad A, Kazem A, Demian SR. Tumor-derived CCL-2 and CXCL-8 as possible prognostic markers of breast cancer: correlation with estrogen and progestrone receptor phenotyping. Egypt J Immunol. 2009;16(2):37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L, Xu L, Yan J, Zhen ZJ, Ji Y, Liu CQ, Lau WY, Zheng L, Xu J. CXCR2-CXCL1 axis is correlated with neutrophil infiltration and predicts a poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res CR. 2015;34:129. doi: 10.1186/s13046-015-0247-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dai Z, Wu J, Chen F, Cheng Q, Zhang M, Wang Y, Guo Y, Song T. CXCL5 promotes the proliferation and migration of glioma cells in autocrine- and paracrine-dependent manners. Oncol Rep. 2016;36(6):3303–3310. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.5155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu X, Qiao Y, Liu W, Wang W, Shen H, Lu Y, Hao G, Zheng J, Tian Y. CXCL5 is a potential diagnostic and prognostic marker for bladder cancer patients. Tumour Biol. 2016;37(4):4569–4577. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4275-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park JY, Park KH, Bang S, Kim MH, Lee JE, Gang J, Koh SS, Song SY. CXCL5 overexpression is associated with late stage gastric cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2007;133(11):835–840. doi: 10.1007/s00432-007-0225-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuo PL, Chen YH, Chen TC, Shen KH, Hsu YL. CXCL5/ENA78 increased cell migration and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of hormone-independent prostate cancer by early growth response-1/snail signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226(5):1224–1231. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong YF, Cheung TH, Lo KWK, Yim SF, Siu NSS, Chan SCS, Ho TWF, Wong KWY, Yu MY, Wang VW, et al. Identification of molecular markers and signaling pathway in endometrial cancer in Hong Kong Chinese women by genome-wide gene expression profiling. Oncogene. 2007;26(13):1971–1982. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyazaki H, Patel V, Wang H, Edmunds RK, Gutkind JS, Yeudall WA. Down-regulation of CXCL5 inhibits squamous carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2006;66(8):4279–4284. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou S-L, Dai Z, Zhou Z-J, Wang X-Y, Yang G-H, Wang Z, Huang X-W, Fan J, Zhou J. Overexpression of CXCL5 mediates neutrophil infiltration and indicates poor prognosis for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2012;56(6):2242–2254. doi: 10.1002/hep.25907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li A, King J, Moro A, Sugi MD, Dawson DW, Kaplan J, Li G, Lu X, Strieter RM, Burdick M, et al. Overexpression of CXCL5 is associated with poor survival in patients with pancreatic cancer. Am J Pathol. 2011;178(3):1340–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu S, Liu Q, Bai X, Zheng X, Wu K. The clinical significance of CXCL5 in non-small cell lung cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2017;10:5561–5573. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S148772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou S-L, Dai Z, Zhou Z-J, Chen Q, Wang Z, Xiao Y-S, Hu Z-Q, Huang X-Y, Yang G-H, Shi Y-H, et al. CXCL5 contributes to tumor metastasis and recurrence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma by recruiting infiltrative intratumoral neutrophils. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35(3):597–605. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altman DG, McShane LM, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2012;9(5):e1001216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(16):1180–1184. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med. 1998;17(24):2815–2834. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19981230)17:24<2815::AID-SIM110>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okabe H, Beppu T, Ueda M, Hayashi H, Ishiko T, Masuda T, Otao R, Horlad H, Mima K, Miyake K, et al. Identification of CXCL5/ENA-78 as a factor involved in the interaction between cholangiocarcinoma cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(10):2234–2241. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kowalczuk O, Burzykowski T, Niklinska WE, Kozlowski M, Chyczewski L, Niklinski J. CXCL5 as a potential novel prognostic factor in early stage non-small cell lung cancer: results of a study of expression levels of 23 genes. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(5):4619–4628. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1605-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han N, Yuan X, Wu H, Xu H, Chu Q, Guo M, Yu S, Chen Y, Wu K. DACH1 inhibits lung adenocarcinoma invasion and tumor growth by repressing CXCL5 signaling. Oncotarget. 2015;6(8):5877–5888. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawamura M, Toiyama Y, Tanaka K, Saigusa S, Okugawa Y, Hiro J, Uchida K, Mohri Y, Inoue Y, Kusunoki M. CXCL5, a promoter of cell proliferation, migration and invasion, is a novel serum prognostic marker in patients with colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(14):2244–2251. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Speetjens FM, Kuppen PJK, Sandel MH, Menon AG, Burg D, van Velde CJH, Tollenaar RAEM, de Bont HJGM, Nagelkerke JF. Disrupted expression of CXCL5 in colorectal cancer is associated with rapid tumor formation in rats and poor prognosis in patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(8):2276–2284. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao J, Ou B, Han D, Wang P, Zong Y, Zhu C, Liu D, Zheng M, Sun J, Feng H, et al. Tumor-derived CXCL5 promotes human colorectal cancer metastasis through activation of the ERK/Elk-1/Snail and AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin pathways. Mol Cancer. 2017;16(1):70. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0629-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang H, Xia W, Lu X, Sun R, Wang L, Zheng L, Ye Y, Bao Y, Xiang Y, Guo X. A novel statistical prognostic score model that includes serum CXCL5 levels and clinical classification predicts risk of disease progression and survival of nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e57830. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strieter RM, Burdick MD, Gomperts BN, Belperio JA, Keane MP. CXC chemokines in angiogenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16(6):593–609. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Persson T, Monsef N, Andersson P, Bjartell A, Malm J, Calafat J, Egesten A. Expression of the neutrophil-activating CXC chemokine ENA-78/CXCL5 by human eosinophils. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33(4):531–537. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2003.01609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao Y, Guan Z, Chen J, Xie H, Yang Z, Fan J, Wang X, Li L. CXCL5/CXCR2 axis promotes bladder cancer cell migration and invasion by activating PI3K/AKT-induced upregulation of MMP2/MMP9. Int J Oncol. 2015;47(2):690–700. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.3041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wente MN, Keane MP, Burdick MD, Friess H, Buchler MW, Ceyhan GO, Reber HA, Strieter RM, Hines OJ. Blockade of the chemokine receptor CXCR2 inhibits pancreatic cancer cell-induced angiogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2006;241(2):221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takahashi H, Numasaki M, Lotze MT, Sasaki H. Interleukin-17 enhances bFGF-, HGF- and VEGF-induced growth of vascular endothelial cells. Immunol Lett. 2005;98(2):189–193. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arenberg DA, Keane MP, DiGiovine B, Kunkel SL, Morris SB, Xue YY, Burdick MD, Glass MC, Iannettoni MD, Strieter RM. Epithelial-neutrophil activating peptide (ENA-78) is an important angiogenic factor in non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Investig. 1998;102(3):465–472. doi: 10.1172/JCI3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou SL, Zhou ZJ, Hu ZQ, Li X, Huang XW, Wang Z, Fan J, Dai Z, Zhou J. CXCR2/CXCL5 axis contributes to epithelial-mesenchymal transition of HCC cells through activating PI3 K/Akt/GSK-3beta/Snail signaling. Cancer Lett. 2015;358(2):124–135. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou SL, Dai Z, Zhou ZJ, Wang XY, Yang GH, Wang Z, Huang XW, Fan J, Zhou J. Overexpression of CXCL5 mediates neutrophil infiltration and indicates poor prognosis for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2012;56(6):2242–2254. doi: 10.1002/hep.25907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou SL, Dai Z, Zhou ZJ, Chen Q, Wang Z, Xiao YS, Hu ZQ, Huang XY, Yang GH, Shi YH, et al. CXCL5 contributes to tumor metastasis and recurrence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma by recruiting infiltrative intratumoral neutrophils. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35(3):597–605. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Imai Y, Kubota Y, Yamamoto S, Tsuji K, Shimatani M, Shibatani N, Takamido S, Matsushita M, Okazaki K. Neutrophils enhance invasion activity of human cholangiocellular carcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma cells: an in vitro study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20(2):287–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brandau S, Dumitru CA, Lang S. Protumor and antitumor functions of neutrophil granulocytes. Semin Immunopathol. 2013;35(2):163–176. doi: 10.1007/s00281-012-0344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao Y, Zhang X, Zhao H, Wang J, Zhang Q. CXCL5 secreted from adipose tissue-derived stem cells promotes cancer cell proliferation. Oncol Lett. 2018;15(2):1403–1410. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith BA, Sokolov A, Uzunangelov V, Baertsch R, Newton Y, Graim K, Mathis C, Cheng D, Stuart JM, Witte ON. A basal stem cell signature identifies aggressive prostate cancer phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(47):E6544–E6552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518007112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Finicelli M, Benedetti G, Squillaro T, Pistilli B, Marcellusi A, Mariani P, Santinelli A, Latini L, Galderisi U, Giordano A. Expression of stemness genes in primary breast cancer tissues: the role of SOX2 as a prognostic marker for detection of early recurrence. Oncotarget. 2014;5(20):9678–9688. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets during and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.