INTRODUCTION

Located on the southeast coast of China, Hong Kong is one of the world’s major financial centres. It is consistently ranked as a highly competitive economic region. Historical shifts involving Chinese immigration and British colonization left the city with a unique “East-meets-West” heritage. Chinese and English are the official languages of Hong Kong, with English being widely used in the government and by the legal, educational, professional, and business sectors.1 After the transfer of sovereignty from Britain to China in 1997, Hong Kong became a special administrative region of the People’s Republic of China, ruled under the principle of “one country, two systems”. This principle ensures that Hong Kong maintains separate political and economic systems from those of China, and that it will have a high degree of autonomy until 2047 (i.e., 50 years after the transfer of sovereignty).1

The population of Hong Kong was estimated at 7.39 million in 2017, making it the sixth most densely populated city worldwide.2,3 In addition to being overpopulated and having the largest number of skyscrapers in the world, Hong Kong is notorious for its high property values and a spectacular night lookout from the Victoria Peak. In terms of population health, the most challenging event in recent history was the epidemic outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (widely known as SARS) in 2003, which led to the deaths of 286 people in Hong Kong, along with pronounced social, economic, and humanitarian repercussions.4 Although there is some cultural affinity with traditional Chinese medicine, people in Hong Kong see Western medicine as the mainstream of medical care. This paper discusses the unique health care system of Hong Kong, including pharmacy practice in the city, based on the building blocks outlined by the Health Systems Framework of the World Health Organization (WHO).

HEALTH SYSTEM LEADERSHIP, GOVERNANCE, AND HEALTH CARE FINANCING

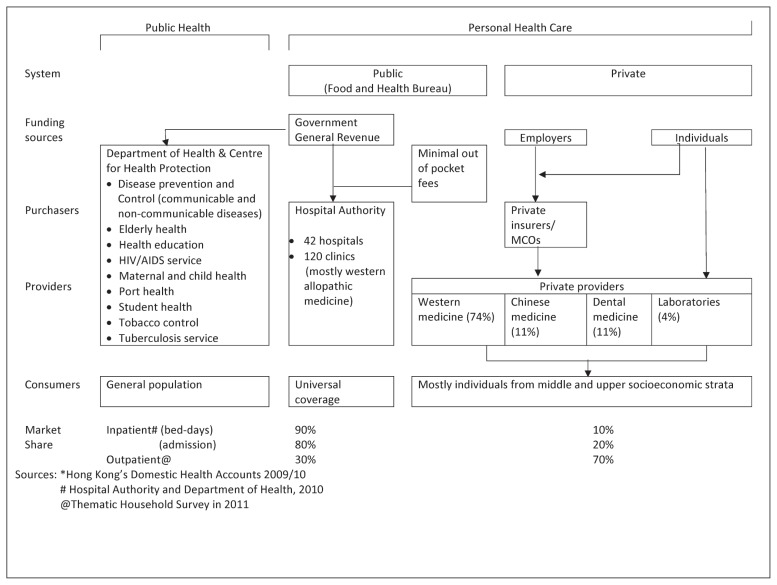

The delivery of health care services in Hong Kong runs along a dual-track model, with services being provided by both the private sector and the government-funded public sector (Figure 1).5 As of December 2015, the number of hospital beds in the city was 38 287, comprising 27 895 beds in 42 public sector hospitals, 4014 beds in 12 private hospitals, 5498 beds in 59 nursing homes, and 880 beds in 29 correctional institutions. The bed–population ratio was 5.2 beds per thousand population. 6 The Food and Health Bureau serves as the highest level of health care governance in Hong Kong. This organization is responsible for formulating, coordinating, and implementing policies related to medical and health issues. It drives the allocation of public resources, with the ultimate aim of providing accessible health care to local citizens and improving population health.7

Figure 1.

Macro-organization of the Hong Kong health system. Reproduced, with permission, from the Food and Health Bureau, Hong Kong SAR Government.5

The public medical service, provided by the Department of Health and the Hospital Authority, is the cornerstone of health care service delivery because of its ready accessibility and low out-of-pocket cost to all residents. The Department of Health is responsible for executing health care policies set forth by the Food and Health Bureau and for providing a broad range of services with public health objectives, including disease prevention and control, tobacco control, maternal and child health, and promotion of health education.5,7 In contrast, the Hospital Authority is a statutory body providing inpatient and outpatient medical services through the universal coverage available to all Hong Kong residents.7 The operation of the Hospital Authority is organized into 7 clusters based on geographic location. Services are delivered through a total of 42 hospitals, 47 specialist clinics, and 73 general outpatient clinics.8 Through these institutions, the Hospital Authority offers a comprehensive range of services, including physician consultation, pharmacy, rehabilitation, day hospitals, Chinese medicine services, and community outreach services.7

As a result of heavy government subsidy, the Hospital Authority can offer relatively high-quality services at minimal charge. Patients have to pay only an out-of-pocket fee of US$13 per day of inpatient stay in Hospital Authority institutions and US$1.30 for each prescription of a formulary drug.6 Given the much lower cost relative to services provided by the private sector, it is not surprising that Hospital Authority services are strongly preferred by most patients.9 Indeed, the Hospital Authority provides about 90% of inpatient services and 30% of outpatient services utilized by the population.5 Considering that a typical public regional hospital in Hong Kong has between 1200 and 1900 beds, with only 20–30 staff pharmacists, it can be deduced that health care staff in the public system have been much overwhelmed by the heavy workload. Meanwhile, patients who do not have an acute illness often experience long waiting times to receive the services they need. Waiting periods of months or years for a consultation or surgery are not uncommon. For example, the average estimated waiting time for cataract surgery ranges from 9 to 27 months, depending on the cluster district where the patient lives.10 The overstretched public service, rising health expenditures in combination with lagging economic growth, and a rapidly aging population present the important question of whether the current health care system is sustainable in the long run.

In contrast to the situation for the public health care sector, the private health care sector provides much timelier, more flexible, and more comfortable services. In 2010, private hospitals provided about 10% of hospital beds and served 21% of inpatients in Hong Kong.7 Patients using the private sector also have the luxury of choosing a particular physician or a particular hospital, and they can schedule surgeries or procedures at a convenient time. Brand-name drug products are often used as well. The pricing of services provided in private hospitals and clinics is based on the actual cost of medical services and drug products, which results in prices at least 10 times higher than similar services in public hospitals. Therefore, despite their comparable quality of medical care and much superior customer service, private medical institutions are not necessarily attractive to the upper socioeconomic class because of the much higher prices they charge.9 Although they are financially independent, all private hospitals and medical clinics must register under the Medical Clinics Ordinance and are regulated by the Department of Health, which monitors compliance with relevant regulations and handles medical incidents and patient complaints.7,11

HEALTH EXPENDITURES

In fiscal year 2016/17, the Hong Kong Government allocated HK$57 billion (US$7.3 billion) to fund medical and health expenses.12 This means that Hong Kong spends about 5.2% of gross domestic product (GDP) or 16.5% of its annual revenue on public health expenditures.12 The funding originates from general revenues of the government, mostly comprising general tax and other public revenues.13 The percentage of revenue spent on health care has increased by 50% since 2010.14 As evidenced by its longevity, Hong Kong’s health care system is perceived to deliver service quality and health outcomes that fare well relative to global standards. The costs of medications used by Hospital Authority patients was HK$5710 million in 2015/16,15 accounting for about 10% of total Hospital Authority expenditure.

Attempts at Health Care Reform

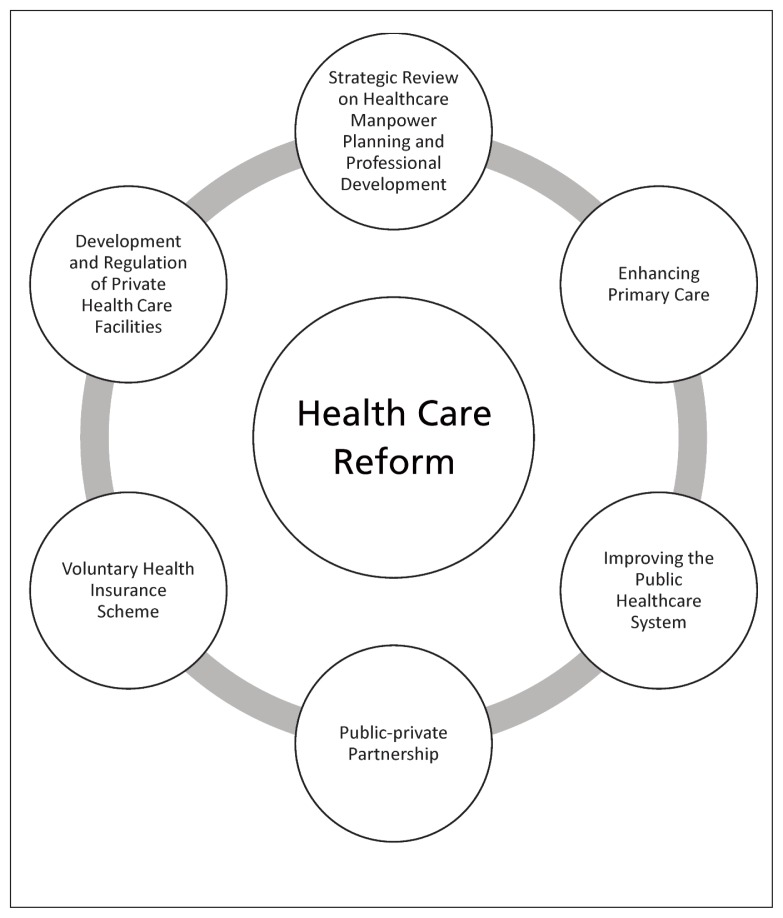

As alluded to above, the aging population and increasing health care costs threaten the long-term sustainability of the Hong Kong health care system. It is therefore necessary to refine the current system, with priorities placed on improving the quality of health care services and optimizing the utilization of private services. Since the 1990s, multiple rounds of public consultation on health care reform have been conducted to identify ways to recalibrate the balance between the public and private health care sectors.16 Various proposals have been put forth, including tightening the control of government subsidies, increasing out-of-pocket fees for public health care services, developing a form of social health insurance, and setting up medical savings accounts.16 Although the public recognizes the need for reform, government proposals have for years failed to draw consensus, and major changes have not been adopted. The most recent plan for health care reform, proposed in 2010, calls for 6 major initiatives (Figure 2),17 of which the most innovative is probably the launch of the Voluntary Health Insurance Scheme, a voluntary, government-regulated private health insurance scheme that may mandate the shift of heavy public service use to private service.17,18 It aims to increase the affordability of private health care services through insurance subscription. By requiring all hospital insurance in the market to comply with a set of minimum standards and providing tax reductions for insurance subscription, the accessibility of private health insurance, and thus private health care, is expected to be enhanced.17,18

Figure 2.

Major initiatives under health care reform in Hong Kong.

Use of Electronic Medical and Health Records

As in many other countries, medical data are usually created and retained by individual health care providers at different locations in diverse formats. To provide the infrastructure to support health care reform and the development of new health care service models such as public–private partnership, a territory-wide, patient-oriented electronic sharing platform named the Electronic Health Record Sharing System was launched in Hong Kong in 2016.19 With the patient’s consent, the Hospital Authority, the Department of Health, and private health care providers will be able to upload and share patients’ electronic health records with other registered health care providers. This scheme will enable more cost-effective use of resources and facilitate decision-making about disease management.

HEALTH INFORMATION

As a result of the well-developed health care system and professional health services, residents of Hong Kong enjoy the longest life expectancy in the world: 87.3 years for women and 81.4 years for men in 2015.20 The infant mortality rate was 1.4 deaths per 1000 births.20 Six types of noncommunicable diseases—cancers, cardiovascular diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, injuries and poisoning, and diabetes mellitus—accounted for 59.7% of all registered deaths in Hong Kong in 2015.20

Population Trends

Like many other Asian countries, the issue of a rapidly aging population poses major threats to the health care system in Hong Kong. The ratio of the working-age population (15–64 years) to the elderly population (65 years or older) is currently 6:1, but by 2033, it is projected to decrease to 3:1.21 This phenomenon is compounded by the large influx of young immigrants from mainland China during the 1960 and 1970s and also the sustained reduction in fertility rate in recent years.21

Promotion of Primary Care Concepts and Public Health Strategies

In recent years, the Hong Kong Department of Health has devoted much effort to disease prevention in the primary care setting. One example of a relatively successful strategy is smoking cessation. The prevalence of smoking has declined markedly, from 23.3% in 1982 to 10.5% in 2015 (a 54.9% reduction over 33 years).22 This significant reduction in the rate of tobacco use can be attributed to the efforts of the Tobacco Control Office of the Department of Health, which has been dedicated in enforcing laws that ban smoking in all indoor public places and in launching educational campaigns. Meanwhile, since 2002, the Hospital Authority has launched a number of Smoking Counselling and Cessation Centres.23 These services are delivered by registered nurses and pharmacists. No data have been made public regarding the program’s success thus far. In the community sector, nicotine replacement therapy is available in different types and formulations at community pharmacies, resembling the practice in most overseas countries. Health care professionals, including pharmacists, have effective channels to provide smoking cessation assessment, counselling, and follow-up.

The WHO has identified antimicrobial resistance as an urgent global threat,24 and this issue is certainly an alarming public health concern in Hong Kong. In fact, local studies have shown that 23.7% of citizens interviewed had received an antibiotic prescription for uncomplicated upper respiratory tract infection from their primary care physicians.25 The illegal sale of antibiotics without prescriptions by some pharmacies further adds to the problem.26 Since the early 2000s, the Hospital Authority has implemented antibiotic stewardship programs in most major hospitals. These programs adopt a multidisciplinary, prospective, interventional approach to optimizing the use of antimicrobials. The multidisciplinary team typically includes a clinical microbiologist, infectious diseases specialist, infection control practitioner, and clinical pharmacist. Every day, the team reviews each patient for whom broad-spectrum antibiotics have been prescribed to ensure optimal selection of agent, dosage, and duration of treatment. The goal of these programs is to achieve the best clinical outcome for the patient, with minimal adverse effects and prevention of subsequent resistance.

Despite these efforts, the number of infections with carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae spiked to 340 in 2016 (from 19 in 2011) according to Hospital Authority reports.27 In view of the imminent problem of escalating antibiotic resistance, the Food and Health Bureau has stepped up its effort to combat high drug resistance rates through the Centre of Health Protection. In 2016, this organization established a high-level steering committee, formed by government officials and experts, to tackle the threat of antimicrobial resistance to public health.27

Scope of Practice and Prescribing Rights of Pharmacists

The Pharmacy and Poisons Board of Hong Kong is established under the Pharmacy and Poisons Ordinance (Cap. 138, Laws of Hong Kong) to carry out functions such as registration and licensing of pharmacists, pharmaceutical products, wholesale dealers, and manufacturers.28 Pharmacists in Hong Kong are not authorized to prescribe or administer vaccines. However, in some public hospitals, pharmacists are allowed to order laboratory tests and change medication dosages according to established protocols. One example of this type of setting is the pharmacist-led warfarin clinic,29 which provides customized patient-focused services, including monitoring of international normalized ratio, patient counselling, dosage adjustment, and prescribing according to an agreed protocol. A local costeffectiveness analysis found that the pharmacist-managed anticoagulation service was more effective and less costly than the physician-managed service.30 In addition, the incidence of bleeding among patients in the pharmacist-managed group was about half that among patients in the physician-managed group.30 Similar types of protocol-driven clinics will be explored in the future to broaden the scope of pharmacy practice.

HEALTH WORKFORCE

As one of its health care reform initiatives, the Government of Hong Kong formulated a health care workforce strategy to ensure an adequate supply of clinical professionals to meet future challenges. In 2012, a steering committee was established to conduct a strategic review of health care workforce planning and professional development in Hong Kong, and its first report was released in June 2017.31 According to the report, in 2016 there were more than 99 000 health care professionals in the 13 disciplines that were examined, including physicians (14.1% of total health care workforce), nurses (52.8%), pharmacists (2.7%), and other allied health professionals. For most disciplines, a human resources shortage by 2020 is projected, but the projection for pharmacists indicates that there will be sufficient human resources in the medium term under the existing service level and model. The report recommended that the Hospital Authority should make full use of human resources to plan for new and enhanced initiatives (e.g., clinical pharmacy services) in response to the challenges of an aging population.31

Educational Requirements

There are 2 universities in Hong Kong that offer a range of undergraduate and postgraduate pharmacy degrees, including a 4-year Bachelor of Pharmacy, a 2-year Master of Clinical Pharmacy, a Master of Philosophy in pharmacy, and a Doctor of Philosophy in pharmacy.32,33 One of the universities also offers a Master of Science in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing and Quality.32 Over the years, the 2 universities have been successful in attracting high-quality students with very high university admission scores. The annual intake for the 2 bachelor-level programs is 90.32,33 The 4-year curriculum covers basic pharmaceutical science, pharmacy practice and dispensing, pharmacology and therapeutics, and other pharmacy-related aspects; it also includes a 6-month practice- or research- oriented clerkship.32,33 Graduates then proceed to a 1-year internship before licensure. For training dispensers, programs leading to a higher-level diploma in pharmaceutical dispensing are offered by 2 community colleges.34,35 The credits obtained from dispenser training are generally not recognized for the local Bachelor of Pharmacy degrees; therefore, those who intend to advance their practice levels will generally have to pursue a Bachelor of Pharmacy degree in another country, such as Australia.

A person who intends to practise as a pharmacist in Hong Kong should first be registered with the Pharmacy and Poisons Board of Hong Kong.36 To be eligible for registration, the applicant must either hold a pharmacy degree awarded by 1 of the 2 local universities or have completed a pharmacy degree in an overseas tertiary educational institution.36 Those in the latter category should be registered as a pharmacist in the country where that education was completed. Overseas graduates will also have to pass written examinations in 3 subjects, namely, pharmacy legislation in Hong Kong, pharmacy practice, and pharmacology.36 Completion of a 1-year period of pre-registration training that involves direct patient care services (i.e., in a community pharmacy or hospital pharmacy) for not less than 6 months is normally required from all applicants.36

An annual licence renewal with fee submission is required to maintain the active status of a pharmacist licence.36 Although no continuing education requirements are mandated by the Pharmacy and Poisons Board of Hong Kong, the Pharmacy Central Continuing Education Committee accredits quality continuing education programs for pharmacists and keeps track of members’ continuing education credit records.37 This committee is a joint collaboration of local pharmacy professional societies and the 2 local universities that train pharmacists.37

Residency Training Program

No accredited pharmacy residency programs are offered in Hong Kong. However, the Hospital Authority offers a resident pharmacist position that provides additional pharmacist training in the hospital. Resident pharmacists undergo a structured residency training program during which they rotate through various departments, including outpatient, inpatient, cytotoxic, and other units. These young pharmacists perform professional duties, including dispensing and drug information handling, and they also complete a residency project under supervision. The training period ranges from 2 years to 7 years.

Specialization and Credentialing of Pharmacists

Recognition of advanced specialty practice is an aspiration for many Hong Kong pharmacists. As of late 2017, a total of 117 Hong Kong pharmacists had attained US Board of Pharmacy Specialties (BPS) certification.38 In September 2010, the College of Pharmacy Practice, an independent, nonprofit professional body, was established with the aim of becoming an independent accreditation-granting authority for the profession in Hong Kong.39 The criteria adopted for granting specialty status by the College of Pharmacy Practice parallel those of the BPS, with an additional requirement of local practice experience.39 Accredited pharmacists will also need to fulfil preapproved continuing education credits to maintain their specialist status.39 At the time of writing, 10 pharmacists had been accredited as oncology or pediatric pharmacists by the College of Pharmacy Practice.39

HEALTH SERVICE DELIVERY

Hospital Practice

As mentioned above, Hong Kong has both private and public hospitals. Both of these sectors partner with the Australian Council on Healthcare Standards to adopt the latest evaluation criteria and quality improvement programs for use in accrediting hospitals.40 Given that the vast majority of services are provided by the public sector, the structure and mode of service delivery of the Hospital Authority will be the focus of the following description.

Pharmacy Service Organizations within the Hospital Authority

The Hospital Authority manages multiple pharmacies in its network cluster of health care facilities, so a combination of centralized and decentralized approaches has been adopted for pharmacy service management. Under this combined approach, decisions on policy and directions for service development are centralized at the head office level, and operations and service delivery are decentralized at the front-line hospital level. This approach demonstrates high efficiency in maintaining uniform practice standards across clusters and optimizes the utilization of expertise and resources. Meanwhile, it allows flexibility at the individual hospital pharmacy level, so that specialized services can be developed to cater to local clinical needs. The head office is responsible for the procurement and management of pharmaceuticals, clinical service and professional development, development and support for Chinese medicine, development of the staff training framework, and the design and implementation of pharmacy information technology applications. At the front-line hospital level, typical pharmacy services include inpatient drug distribution, specialized drug reconstitution, outpatient dispensing and counselling, and clinical pharmacy activities. The pharmacy department of each hospital also provides administrative support to the Medication Incident Reporting Program and the Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting Program. These programs were established centrally to record adverse incidents and to review and analyze their causes, occurrences, and consequences. Furthermore, 2 of the Hospital Authority hospitals are designated as teaching hospitals, collaborating with the 2 local universities on training and academic research.

Local hospital pharmacists have been heavily involved in traditional drug distribution and dispensing duties, which are considered the core functions of a pharmacy. A survey conducted in 2008 found that drug distribution (55.5%), clinical activities (20.5%), and general management (18.6%) constituted the major aspects of hospital pharmacist activities in the public sector.41 The clinical activities in which greater numbers of pharmacists were involved included drug information services, patient education, and drug therapy monitoring. The survey also indicated a desire to shift from drug dispensing– oriented functions to greater involvement in clinical pharmacy activities.41 In the past decade, the Hospital Authority has been seeking to expand the clinical services that hospital pharmacists in Hong Kong can offer. A paradigm shift from mere product dispensing to more patient-oriented delivery of pharmacy service has been promoted, albeit under limited resources. Across the 7 clusters, various clinical services such as medication reconciliation, antibiotic stewardship, pediatrics, and oncology services have been developed. A medication compliance clinic, pharmacist participation in ward rounds, and pharmacist participation in risk management are available in most large acute care hospitals.42 Unfortunately, because of limited human resources and overwhelming workload, most pharmacists who take up clinical duties are still expected to fulfil the front-line dispensing needs. Especially during peak influenza seasons and high staff turnover periods, pharmacists may not be attending to their clinical activities consistently, and it may not be possible to sustain some of these services. As a result of inadequate support and lack of additional incentives, the coverage and quality of services provided are suboptimal, which in turn hinder growth of services in the long term.

Acquisition of a postgraduate professional degree is common among pharmacists in the hospital setting. To date, most junior pharmacists in Hong Kong pursue a master’s degree in clinical pharmacy for accelerated career advancement from resident pharmacist to pharmacist. To better prepare pharmacists for clinical duties, the Hospital Authority has developed competency framework and training requirements for pharmacists with various level of experience. With input from the local academic institutions, training programs are designed to encompass a wide range of knowledge and skill set enhancement relating to clinical patient assessment, medication reconciliation, drug therapy assessment, and intensive advanced-topic pharmacotherapy. Overseas clinical placements are also provided to most pharmacists appointed to deliver specialized services.

Pharmacy Automation

Automation systems are strongly embraced by all of the local hospitals. These applications are widely adopted in areas such as procurement and supplies management, maintenance of inpatient medication profiles, automatic refills, top-up system for bar-coded ward stock, computerized physician order entry for inpatient drug distribution, and express dispensing systems for outpatient dispensing. These systems allow high operational efficiency in the face of an overwhelming patient load and allow pharmacists to perform clinical duties in the patient care process. An important byproduct of this approach is the accumulation of an enormous amount of accurate drug data in standardized format. This invaluable information source allows analysis of prescribing patterns, drug consumption trends, and drug histories. The data can also be retrieved for research purposes.

Community Pharmacy Practice

There are 2 main types of community pharmacies in Hong Kong: independently owned pharmacies and chain pharmacies. Because there is still no separation of dispensing from prescribing in Hong Kong, the number of prescriptions received in community pharmacies is small, ranging from 10 to 30 per week. Pharmacists in the community setting are often underutilized. Their other duties include recommending over-the-counter products, advising on the management of minor aliments, and maintaining sufficient stock levels.

Unfortunately, because drug dispensing regulations are not strictly enforced, patients can often obtain some commonly used medications without prescriptions in some of the independently owned pharmacies through nonpharmacist personnel. Meanwhile, the dispensing of medications in private medical clinics is often not supervised by pharmacists.

Industrial Pharmacy Practice

Most international pharmaceutical companies have country offices in Hong Kong. Although extensive manufacturing, research, and development may not be feasible, the local offices focus on medical affairs, and on sales and marketing of pharmaceutical products in Hong Kong. Besides international companies, more than 30 local pharmaceutical manufacturers are based in Hong Kong; these companies mainly supply medicines to the local and mainland markets.43

Good manufacturing practices (GMP) were adopted in Hong Kong in 2002 to facilitate the regulation of the Western drug manufacturing industry and to ensure the quality and safety of pharmaceutical products. In early 2009, a fatal incident involving allopurinol tablets contaminated with Rhizopus microsporus during the manufacturing process was reported.44 This incident, along with other incidents reported in the same year, aroused major media attention and raised the public’s concern about quality control of drug manufacturing processes. The Food and Health Bureau and the Department of Health took immediate measures to address these concerns, undertaking a comprehensive review of the existing regime for regulating pharmaceutical products. The Review Committee on Regulation of Pharmaceutical Products in Hong Kong was soon set up.45

After 6 months of discussion, the committee put forward 75 recommendations, including upgrading Hong Kong’s current GMP licensing standards to meet the Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme—Guide to Good Practices for the Preparation of Medicinal Products in Healthcare Establishments within 4 years.45 The upgrade was intended to enhance the practice standards and production of local drug manufacturers. In subsequent years, the Department of Health and local pharmaceutical manufacturers have been making efforts to ensure compliance with the recommendations. In October 2015, the Pharmacy and Poisons Board of Hong Kong, the licensing body for local manufacturers, officially adopted the Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme guide to GMP as one of the licensing conditions for local manufacturers.46

One of the specifications of the Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme guide to GMP requires an authorized person to certify that the production of each batch of drug products is in accordance with quality control standards. The authorized person is normally expected to be a registered pharmacist with at least 3 years of experience in the manufacturing or quality control area of a pharmaceutical manufacturer.47 Besides practising as authorized persons in this capacity, pharmacists often work in the quality control, regulatory affairs, and sales and marketing arenas in the pharmaceutical industry.

Pharmacists in Academia

Only 2 local universities in Hong Kong provide pharmacy education, so the number of pharmacists working in the academic sector constitutes a very small part of the workforce. Similar to the situation in overseas countries, there are high expectations for pharmacists in academia to perform research, education, and service. Academic staff in Hong Kong are also engaged in various professional activities and local pharmacy conferences. Joint appointments between teaching hospitals and the universities had been explored in the past; unfortunately, such collaboration was not supported because of funding complications. Recently, the issue has been revisited, which carries hope for establishing formal collaborative models.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

For decades, Hong Kong residents have taken pride in the city’s efficient health care system, in which a low percentage of GDP is spent on health care, achieving the top longevity in the world. Interestingly, this longevity, leading to an aging population and increased medical costs, challenges the sustainability of the already-overloaded and heavily government-subsidized public health care system. In anticipation of future problems, the government has called for health care reform focused on promoting public–private partnership, sharing of electronic health records, and workforce review, among other measures. All of these steps will be instrumental in enhancing utilization of the private health care sector, with the ultimate goal of improving the quality and sustainability of the overstretched health care system. In fact, the pharmacy profession is just as underutilized as the private health care sector, if not more. By supporting government-directed initiatives, the pharmacy profession in Hong Kong is at a watershed moment to seize or create opportunities to revolutionize its professional roles.

An important strength of the Hong Kong pharmacy profession is the talented and passionate professional bodies with which it is gifted. Numerous initiatives to revolutionize pharmacists’ roles have been proposed and executed through the relentless efforts of these professional bodies. These initiatives have included accrediting specialist pharmacists, expanding pharmacy services to nursing homes, providing professional continuous education credits, and proposing a pharmacist-incorporated team approach to primary health care. In addition, thanks to the efforts of these professional bodies in delivering extensive public drug education through exhibitions and social media, there has been a shift in public perceptions, with members of the public now able to distinguish pharmacists as medication experts from those who simply dispense medications. In view of the drive for public–private partnerships, the professional bodies have also proposed various ways to involve community pharmacists. Public–private collaborative dispensing or refill programs that incorporate community pharmacist consultation during lengthy intervals between physician visits have been proposed to the government. Despite these efforts, progress in achieving government recognition is rather slow, because of various political considerations and resource implications. Recently, in some good news for the profession, the latest (2017) policy address from the Hong Kong Chief Executive includes a proposal to increase the number of pharmacists in order to strengthen clinical pharmacy services, especially in the public sector. Effort will also be devoted to identifying means for better resource deployment to improve nursing home pharmacy services.48 This represents recognition at the highest level of the administration, with promising prospects for policy implementation.

Another important aspiration of local pharmacists is to establish the Pharmacy Council, on par with the existing Medical Council and Nursing Council. Currently, the profession’s only regulatory body is the Pharmacy and Poisons Board of Hong Kong, which claims a passive, purely regulatory role. Establishing a Pharmacy Council with statutory status and a clear aim of advancing the professional standards of pharmacy practice will be much more effective in nurturing growth of the profession. This council will also position itself as a strong advocate for re-branding of the profession and guiding its further development. In fact, a task force on a pre-pharmacy council has been set up by the universities and professional bodies. The task force has conducted extensive work in terms of proposing the necessary infrastructure, defining roles, and lobbying for government support. Moving forward, the profession will need to make a passionate case to arouse the attention of the public, stakeholders, and government officials to support legislation leading to the establishment of the Pharmacy Council.

In the near future, the profession will continue its pursuit of successful health care reform by making efforts in multiple directions. Pharmacists will also gear themselves toward working constructively with the government and other health care professionals with a common goal of making health care provision in Hong Kong a well-rounded pursuit with optimal utilization of both pharmaceuticals and pharmacists.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Chiang Sau Chu for her invaluable contribution in providing supportive information.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Hong Kong – the facts. Hong Kong: The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www.gov.hk/en/about/abouthk/facts.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hong Kong statistics. Hong Kong: Census and Statistics Department; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.censtatd.gov.hk/hkstat/sub/bbs.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith O. Mapped: the world’s most overcrowded cities. London (UK): Telegraph Media Group Limited; 2017. Aug 31, [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/lists/most-overcrowded-cities-in-the-world/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SH. The SARS epidemic in Hong Kong: what lessons have we learned? J R Soc Med. 2003;96(8):374–8. doi: 10.1177/014107680309600803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun C. Healthcare reform in Hong Kong: supplementary financing in a mixed healthcare economy. Hong Kong: Food and Health Bureau, Healthcare Planning and Development Office; 2013. Mar 7, [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.actuaries.org.hk/upload/File/ASHK%20Healthcare%20Seminar%202013/Healthcare%20Reform%20in%20Hong%20Kong%20-%20FHB.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Overview of the health care system in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; 2017. Oct, [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www.gov.hk/en/residents/health/hosp/overview.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong Kong: the facts; public health. Hong Kong: The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; 2016. Feb, [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www.gov.hk/en/about/abouthk/factsheets/docs/public_health.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hospital authority: cluster, hospitals & institutions. Hong Kong: Hospital Authority; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.ha.org.hk/visitor/ha_visitor_index.asp?Content_ID=10084&Lang=ENG&Dimension=100&Parent_ID=10042. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong ELY, Coulter A, Cheung AWL, Yam CHK, Yeoh EK, Griffiths SM. Patient experiences with public hospital care: first benchmark survey in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2012;18(5):371–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waiting time for cataract surgery. Hong Kong: Hospital Authority; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.ha.org.hk/visitor/ha_visitor_text_index.asp?Content_ID=214184&Lang=ENG&Dimension=1. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Office for Regulation of Private Healthcare Facilities. Hong Kong: Department of Health; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.dh.gov.hk/english/main/main_orphf/main_orphf.html. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsang JC. The 2016–17 budget. Hong Kong: The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; 2016. Feb 24, [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www.budget.gov.hk/2016/eng/pdf/e_budgetspeech2016-17.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fact sheet: major sources of government revenue. Hong Kong: Research Office of Legislative Council Secretariat; 2015. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.legco.gov.hk/research-publications/english/1415fs03-major-sources-of-government-revenue-20150907-e.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Domestic health accounts. Hong Kong: Food and Health Bureau; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.fhb.gov.hk/statistics/en/dha/dha_summary_report.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Audit Commission. Hospital Authority: Hospital Authority’s drug management. Hong Kong: The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; 2017. [cited 2018 Feb 17]. Available from: www.aud.gov.hk/pdf_e/e67ch05.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramesh M. Healthcare reform in Hong Kong: the politics of liberal non-democracy. Pac Rev. 2012;25(4):455–71. doi: 10.1080/09512748.2012.685095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.My health my choice: healthcare reform second stage consultation document. Hong Kong: Food and Health Bureau; 2010. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.myhealthmychoice.gov.hk/pdf/consultation_full_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Voluntary Health Insurance Scheme: full consultation document. Hong Kong: Food and Health Bureau; 2017. Oct, [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.vhis.gov.hk/en/public_consultation/full_consultation_document.html. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Electronic Health Record Sharing System: what is HR sharing system? Hong Kong: Food and Health Bureau; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.ehealth.gov.hk/en/about_ehrss/electronic_health_record/what_is_ehrss.html. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Updates to health information library. Hong Kong: Department of Health, Healthy HK; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.healthyhk.gov.hk/phisweb/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong Kong population projections 2015–2064. Hong Kong: Census and Statistics Department; 2015. Sep, [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B1120015062015XXXXB0100.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smoking. Hong Kong: Centre for Health and Protection; 2016. May 18, [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.chp.gov.hk/en/content/9/25/8806.html. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cessation services. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Council on Smoking and Health; 2016. [cited 2018 Feb 17]. Available from: http://smokefree.hk/en/content/web.do?page=Services. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antimicrobial resistance. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lam TP, Lam KF, Ho PL, Yung RWH. Knowledge, attitude, and behaviour toward antibiotics among Hong Kong people: local-born versus immigrants. Hong Kong Med J. 2015;21(6 Suppl 7):S41–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernandes N. Illegal sale of antibiotics still common in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong, Journalism and Media Studies Centre; 2017. Mar 20, [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: https://jmsc.hku.hk/2017/03/illegal-sale-of-antibiotics-still-common-in-hong-kong/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong Kong strategy and action plan on antimicrobial resistance 2017–2022. Hong Kong: Centre for Health and Protection, High Level Steering Committee on Antimicrobial Resistance; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/amr_action_plan_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Functions of the Board. Hong Kong: Pharmacy and Poisons Board of Hong Kong; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.ppbhk.org.hk/eng/functions/functions.html. [Google Scholar]

- 29.You JH, Chan FW, Wong RS, Lai MW, Chan EM, Cheng G. Outcomes of long-term warfarin therapy under two ambulatory care models in Hong Kong [letter] Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2003;60(16):1692–4. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/60.16.1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.You JHS, Cheng G, Chan TYK. Comparison of a clinical pharmacist-managed anticoagulation service with routine medical care: impact on clinical outcomes and health care costs. Hong Kong Med J. 2008;14(Suppl 3):S23–7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strategic review on healthcare manpower planning and professional development. Hong Kong: Healthcare Planning and Development Office; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.hpdo.gov.hk/en/srreport.html. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Education. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong, School of Pharmacy; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.pharmacy.cuhk.edu.hk/1/education/ [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bachelor of Pharmacy. Hong Kong: The University of Hong Kong, Department of Pharmacology and Pharmacy; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.pharma.hku.hk/web2/bphm/index2.php. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higher diploma in pharmaceutical dispensing (full-time/part-time) Hong Kong: Caritas Bianchi College of Careers; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.cbcc.edu.hk/eng/programmes/fulltime/hs/hd.html. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higher diploma in dispensing studies. Hong Kong: Vocational Training Council; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.vtc.edu.hk/admission/en/programme/as124203-higher-diploma-in-dispensing-studies/ [Google Scholar]

- 36.Registration requirements. Hong Kong: Pharmacy and Poisons Board of Hong Kong; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.ppbhk.org.hk/eng/registration_pharmacists/qualifications.html. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pharmacy Central Continuing Education Committee [home page] Hong Kong: Pharmacy Central Continuing Education Committee; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.pccchk.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 38.Find a board certified pharmacist. Washington (DC): Board of Pharmacy Specialties; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www.bpsweb.org/find-a-board-certified-pharmacist/ [Google Scholar]

- 39.Welcome to the College of Pharmacy Practice. Hong Kong: College of Pharmacy Practice; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: http://www.cpp.org.hk/ [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hospital accreditation. Hong Kong: Hospital Authority; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: https://accred.ha.org.hk/hosp_accred/default.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lau WM, Pang J, Chui W. Job satisfaction and the association with involvement in clinical activities among hospital pharmacists in Hong Kong. Int J Pharm Pract. 2011;19(4):253–63. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7174.2010.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strategic plans for pharmaceutical services. Hong Kong: Hospital Authority, Medical Development Committee; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43.List of registered importers and exporters of pharmaceutical products. Hong Kong: Department of Health, Drug Office; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www.drugoffice.gov.hk/eps/do/en/pharmaceutical_trade/news_informations/relicList.html?indextype=9A. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Annex G. Report of the Review Committee on Regulation of Pharmaceutical Products in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Food and Health Bureau; 2017. Chronology of drug incidents since March 2009. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.fhb.gov.hk/download/press_and_publications/otherinfo/100105_pharm_review/en_annex_g.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Report of the Review Committee on Regulation of Pharmaceutical Products in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Food and Health Bureau; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.fhb.gov.hk/en/press_and_publications/otherinfo/100105_pharm_review/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pharmacy and Poisons Board of Hong Kong accedes to Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme. Hong Kong: Pharmacy and Poisons Board of Hong Kong; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: www.ppbhk.org.hk/eng/index_content9.html. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guidance on qualification, experience and training requirements for authorized persons and other key personnel of licensed manufacturers in Hong Kong Version 6.3.1. Hong Kong: Department of Health, Drug Office; 2017. [cited 2017 Nov 17]. Available from: https://www.drugoffice.gov.hk/eps/do/en/doc/guidelines_forms/Guidance_on_Qualification.pdf?v=i2qss. [Google Scholar]

- 48.The chief executive’s 2017 policy address. Hong Kong: The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; 2017. Section V: Improving people’s livelihood. [cited 2018 Feb 17]. Available from: https://www.policyaddress.gov.hk/2017/eng/policy_ch05.html. [Google Scholar]