Abstract

Mutations in the gene encoding the protein kinase A (PKA) catalytic subunit α have been found to be responsible for cortisol-producing adenomas (CPAs). In this study, we identified by whole-exome sequencing the somatic mutation p.S54L in the PRKACB gene, encoding the catalytic subunit β (Cβ) of PKA, in a CPA from a patient with severe Cushing syndrome. Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer and surface plasmon resonance assays revealed that the mutation hampers formation of type I holoenzymes and that these holoenzymes were highly sensitive to cAMP. PKA activity, measured both in cell lysates and with recombinant proteins, based on phosphorylation of a synthetic substrate, was higher under basal conditions for the mutant enzyme compared with the WT, while maximal activity was lower. These data suggest that at baseline the PRKACB p.S54L mutant drove the adenoma cells to higher cAMP signaling activity, probably contributing to their autonomous growth. Although the role of PRKACB in tumorigenesis has been suggested, we demonstrated for the first time to our knowledge that a PRKACB mutation can lead to an adrenal tumor. Moreover, this observation describes another mechanism of PKA pathway activation in CPAs and highlights the particular role of residue Ser54 for the function of PKA.

Keywords: Endocrinology, Genetics

Keywords: Molecular genetics, Protein kinases

An activating mutation in the PRKACB gene encoding the beta isoform of PKA catalytic subunit can lead to cortisol-producing adenomas.

Introduction

The cAMP pathway is one of the most important signaling pathways in adrenocortical cells, and is involved in their regulation of growth and steroidogenesis. Under normal conditions, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) binds to its G protein–coupled receptor, the melanocortin 2 receptor, which via the activation of the α-stimulating subunit of the guanine nucleotide–binding protein (Gsα), stimulates adenyl cyclase and thereby cAMP production. Protein kinase A (PKA) is a tetrameric enzyme composed of a regulatory (R) dimer and 2 catalytic (C) subunits. Binding of 2 cAMP molecules to each R subunit leads to holoenzyme dissociation and subsequent phosphorylation of substrates by the C subunits (1). There are 4 different R subunits (RIα, RIβ, RIIα, and RIIβ) and 4 C subunits (Cα, Cβ, Cγ, and protein kinase X). Cα and protein kinase X are ubiquitously expressed, whereas Cβ has a more limited pattern of expression and Cγ is mainly expressed in testis (2). Type I PKA holoenzyme corresponds to the tetramers formed with the type I R subunits (RIα and RIβ), while type II PKA holoenzyme corresponds to the tetramers formed with type II R subunits (RIIα and RIIβ).

Activation of the PKA pathway has been described in several adrenal diseases with Cushing syndrome (CS): germline mutations of protein kinase cAMP-dependent type I regulatory subunit α (PRKAR1A, encoding the subunit RIα of PKA) cause Carney complex and primary pigmented nodular adrenal disease; mosaic mutations of GNAS (encoding for Gsα) lead to McCune-Albright syndrome, which can be associated with bilateral adrenal hyperplasia; germline variants of the gene encoding for phosphodiesterase 11A favor the development of primary pigmented nodular adrenal disease and primary bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia, and germline and somatic mutations of the gene encoding for phosphodiesterase 8B have been described in micronodular adrenocortical disease and primary bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia, respectively (3). Somatic mutations of PRKAR1A and GNAS have been found in cortisol-producing adenomas (CPAs) (3). In 2014, several groups demonstrated the involvement of somatic mutations of protein kinase cAMP-activated catalytic subunit α (PRKACA, encoding for the Cα subunit of PKA) in about 40% of CPAs (4–7). All PRKACA mutations found in CPA to date lead to loss of interaction with the R subunits and consequently an increase of total PKA activity (8).

In this study, we identified a mutation in the protein kinase cAMP-activated catalytic subunit β gene (PRKACB, encoding the Cβ isoform of PKA) and confirmed in vitro that the mutation affects type I PKA holoenzyme function.

Results

Identification of a potentially novel PRKACB gene mutation.

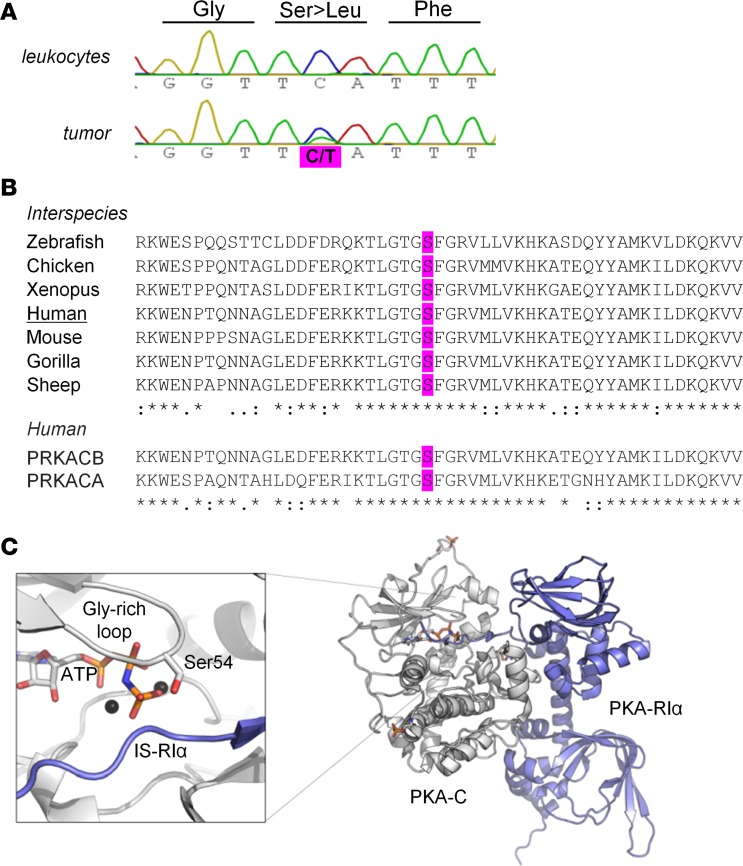

To identify new candidate genes responsible for CPA, we performed whole-exome sequencing of 6 paired leukocyte and tumor DNA samples. Somatic mutations in genes involved in the cAMP/PKA pathway were found in 5 of 6 tumors including missense mutations in PDE8B (n = 1), GNAS (n = 2), PRKACA (n = 1), and PRKACB (n = 1). Other mutations identified after filtering are presented in Supplemental Table 1 (supplemental material available online with this article; https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.98296DS1). In the adenoma harboring the PRKACB mutation, no other relevant genetic defects could be identified. Sanger sequencing of tumor and leukocyte DNA of the patient confirmed the presence of the somatic mutation c.161C>T, p.S54L in PRKACB (NM_002731) (Figure 1A). Sequencing of coding sequences and flanking introns of PRKACB in the tumor DNA from another 21 WT-PRKACA CPAs did not show any other mutations. In addition, reviewing the literature indicated that no other PRKACB mutation was described in published whole-exome sequences of 164 CPAs (4–7, 9).

Figure 1. Somatic mutation at the conserved serine 54 of PRKACB.

(A) Partial electropherograms of the PRKACB gene showing a canonical sequence in the leukocytes of the patient and the c.161C>T (S54L) mutation in the tumor (according to the variant NM_002731). (B) Multiple alignments of PRKACB sequences (performed with CLUSTAL O 1.2.1) showing that the residue S54L is conserved between different isoforms and species. (C) Crystal structure of the PKA holoenzyme complex. The catalytic subunit (Cα) is in white, and the regulatory subunit (RIα) is in blue. On the left, magnification of the active site shows Ser54 of the glycine-rich loop, which is involved in binding of the cosubstrate ATP (orange sticks) and substrates (here the pseudosubstrate sequence of RIα). S54L is located in the immediate vicinity of the inhibitor sequence of the regulatory subunit. The structure (PDB 2QCS) was visualized using PyMOL v1.3 (Schrödinger LLC).

In silico modeling of S54L mutant.

Serine 54 (Ser54) is conserved in the human Cα, Cβ, and Cγ sequences, as well as in that of other species (Figure 1B). This residue is located at the tip of the glycine-rich loop (G-loop) (Figure 1C). The mutation S54L was predicted to be damaging by MutationTaster (probability: 0.99999) and SIFT (score: 0), and benign by Polyphen2 (score: 0.441).

Patient description.

The patient was a 41-year-old woman referred to our clinic for the investigation and treatment of CS. She developed all the stigmata of clinical CS complicated by hypertension, venous thrombosis, osteoporosis with vertebral fractures, dyslipidemia, and hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Biological evaluation showed ACTH-independent CS: loss of cortisol circadian rhythm with plasma midnight cortisol at 217 ng/ml (normal [N]: <75 ng/ml), midnight salivary cortisol at 6.3 ng/ml (N: <2 ng/ml), urinary free cortisol (UFC) at 333 μg/24 hours (N: 25–90), and lack of cortisol suppression upon standard dexamethasone suppression test (2 mg/day) (UFC at 451 μg/24 hours [N: <10]). There was no aldosterone or androgen oversecretion. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed a 3-cm left-adrenal nodule with a spontaneous density of 47 Hounsfield units. On magnetic resonance imagery, the left nodules did not demonstrate a loss of signal intensity on opposed-phase images and the drop in signal intensity was lower than 20% in out-of-phase images in favor of an atypical adenoma. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-CT and 131I-noriodocholesterol scintigraphy showed increased uptake by the left nodules. The patient underwent left adrenalectomy. Histological examination showed a 3-cm yellow and pigmented adenoma compound of compact adrenocortical cells with islet of spongiocytes cells and clusters of adipocytes with lymphoid infiltration. The Weiss score was 1. The patient was cured of CS and developed adrenal insufficiency postoperatively, for which she was treated.

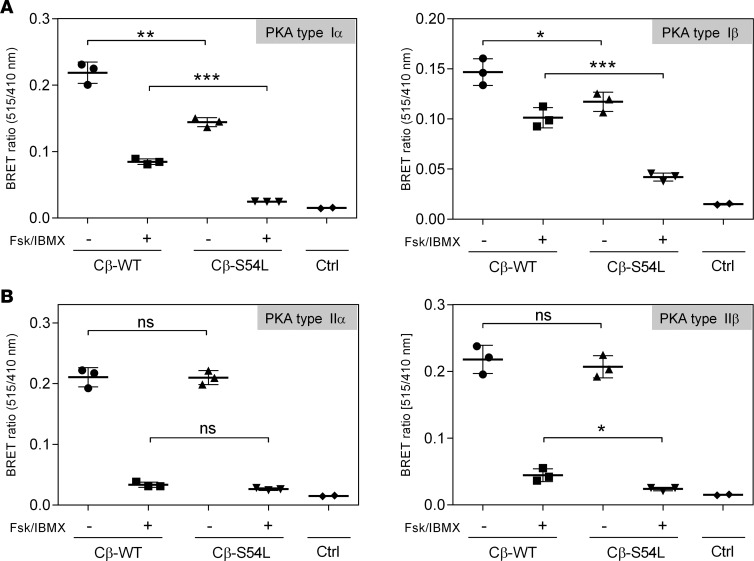

PRKACB mutation S54L affects stability for type I but not for type II PKA holoenzyme.

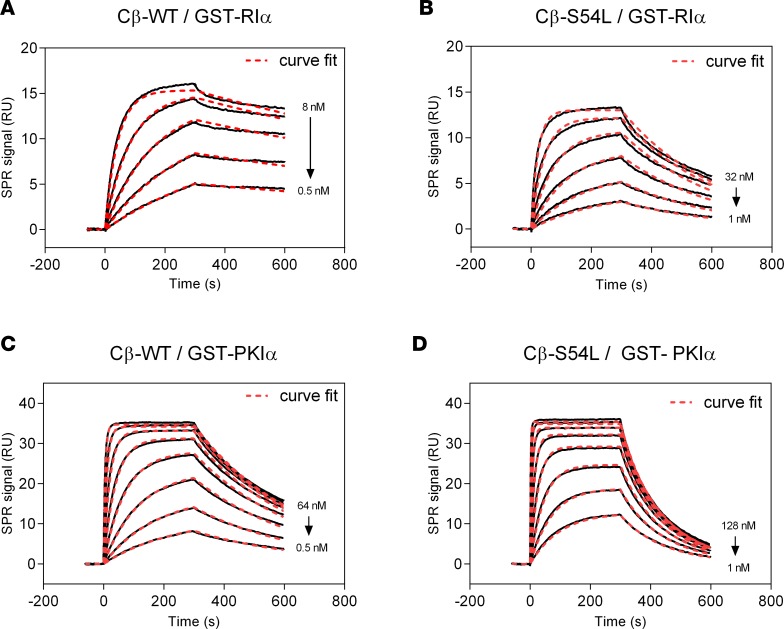

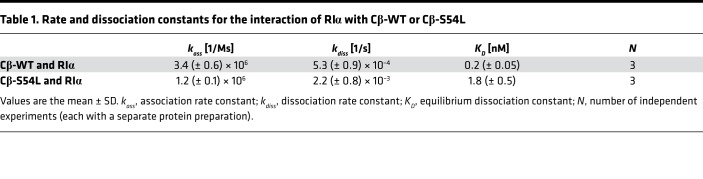

To provide in vitro evidence for the pathogenicity of the S54L mutation, we first tested whether the S54L mutation affects PKA holoenzyme formation. We used a cell-based bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) assay as described previously (10) based on transient coexpression of a luciferase-tagged R subunit (either RIα, RIβ, RIIα, or RIIβ) as a donor and GFP-tagged versions of either the WT or mutant (S54L) Cβ subunit (isoform 1, Cβ1) as an acceptor. The BRET ratio (ratio of acceptor and donor emission) was significantly lower under basal conditions as well as after stimulation with forskolin and 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) for type I mutant holoenzymes (RIα/Cβ-S54L and RIβ/Cβ-S54L) compared with the respective WT holoenzymes (Figure 2A). Formation of type II holoenzymes (RIIα/Cβ-S54L and RIIβ/Cβ-S54L) was not affected by the S54L mutation (Figure 2B). In order to validate that the S54L mutation affects type I holoenzyme formation, we expressed mutant and WT Cβ1 as recombinant proteins in E. coli and checked for holoenzyme formation in vitro using surface plasmon resonance (SPR). Compared with WT, the S54L mutant showed a 10-fold-reduced affinity for the RIα subunit (Figure 3, A and B, and Table 1). This was mainly due to a 4-fold-faster dissociation rate reflecting weaker interaction of the holoenzyme complex (Table 1). Injecting 30 nM cAMP after holoenzyme formation resulted in pronounced dissociation of the mutant holoenzyme, while the WT was almost unaffected at this concentration (Figure 4A). Interestingly, inhibition by the other physiological inhibitor of PKA, heat-stable protein kinase inhibitor α (PKIα), was only slightly affected (Figure 3, C and D, and Table 2).

Figure 2. Mutant type I PKA holoenzyme stability is decreased in HEK293 cells.

Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) experiments were used to test PKA type I (A) and type II (B) holoenzyme formation and dissociation. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with RLuc-tagged regulatory subunits (RIα or RIβ in panel A and RIIα or RIIβ in panel B) as a donor (emission 410 nm) and GFP-tagged catalytic subunits (wild-type [WT] or mutant [S54L] Cβ isoform 1) as an acceptor (emission 515 nm). Cells were treated either with buffer (basal condition, black boxes) or with 50 μM adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin (Fsk) and 100 μM phosphodiesterase inhibitor 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) to induce holoenzyme dissociation (stimulated condition, white boxes). Transfection of the empty RLuc8 vector was used as control (Ctrl). (A) The BRET ratio is significantly lower in basal and stimulated conditions for type I holoenzymes with the S54L mutant compared with the WT, indicating a decrease in mutant holoenzyme formation and stability. (B) No significant differences in BRET ratio were observed under basal conditions for the type II holoenzymes, indicating that the S54L mutation does not disturb the holoenzyme formed with type II regulatory subunits. Data from 3–6 replicates from 3 independent experiments are represented as dot plots and analyzed by unpaired t test with Sidak’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. ns, not significant.

Figure 3. Binding of PKA-Cβ to physiological pseudosubstrate inhibitors.

Binding affinity of Cβ-WT (A and C) or Cβ-S54L (B and D) was determined using surface plasmon resonance (SPR). For this, recombinant RIα subunit (A and B) or the protein kinase inhibitor α (PKIα) (C and D) were captured on a sensor chip. Recombinant Cβ-WT (A and C) or Cβ-S54L (B and D) were injected for 300 seconds at different concentrations (association). Dissociation of the complex was monitored for 300 seconds. Equilibrium binding constants and rate constants were determined using a Langmuir 1:1 binding model (curve fits are depicted as red dashed lines in representative plots) and are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. The reduced affinities for RIα and PKIα determined for the mutant Cβ-S54L compared with the WT protein are mainly due to faster complex dissociation (see Tables 1 and 2 for dissociation rates). RU, response units.

Table 1. Rate and dissociation constants for the interaction of RIα with Cβ-WT or Cβ-S54L.

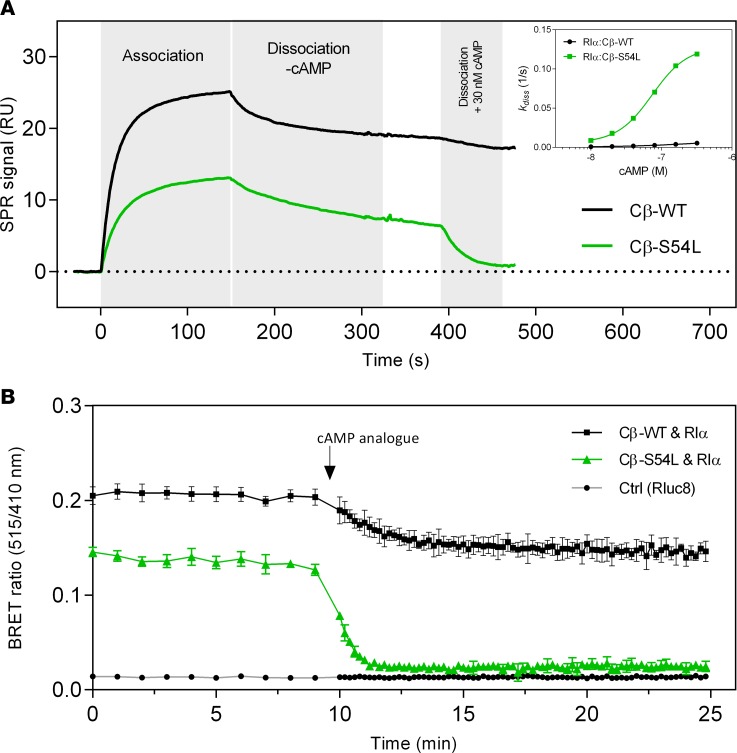

Figure 4. Mutant type I PKA holoenzyme is more sensitive to cAMP.

(A) In this surface plasmon resonance (SPR) experiment, recombinant RIα subunit was captured on a sensor chip and WT or S54L Cβ were injected for 150 seconds (15 nM concentration in this representative experiment), demonstrating a decrease of the mutant holoenzyme complex formation. After 150 seconds the system was switched to buffer, allowing the monitoring of complex stability in the absence of cAMP. After 400 seconds, supplementation of buffer with 30 nM cAMP caused a rapid dissociation of the mutant holoenzyme, whereas the WT holoenzyme was almost unaffected. The inset shows the dissociation rate at several cAMP concentrations. These data clearly demonstrate an increased cAMP sensitivity of the mutant type I holoenzyme. (B) In this bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) time-course experiment, 100 μM cell-permeant cAMP analog (8-Br-cAMP-AM) was injected after a 10-minute baseline measurement. A rapid and full dissociation was observed for the mutant holoenzyme, while the WT showed slow and only partial dissociation. Values are given as mean ± SD from 6 individual transfections. RU, response units.

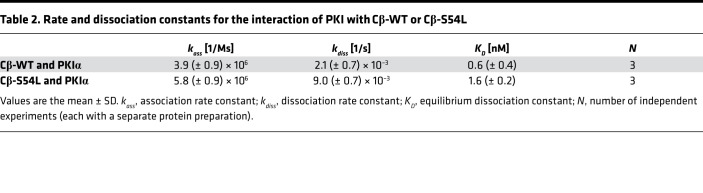

Table 2. Rate and dissociation constants for the interaction of PKI with Cβ-WT or Cβ-S54L.

The increased cAMP sensitivity of the S54L type I holoenzyme was verified in a spectrophotometric kinase activity assay. The activation constant (Kact), reflecting the concentration of cAMP required to obtain 50% of maximal activity, was 3-fold higher for the WT holoenzyme than for the mutant (Table 3). In order to verify this higher cAMP sensitivity, we again utilized BRET to investigate the time course of holoenzyme activation in living cells. After injection of a cell-permeant cAMP analog (8-Br-cAMP-AM), cells expressing the WT holoenzyme showed slow and only partial dissociation of the holoenzyme, while those expressing the mutant holoenzyme showed rapid and complete dissociation (Figure 4B).

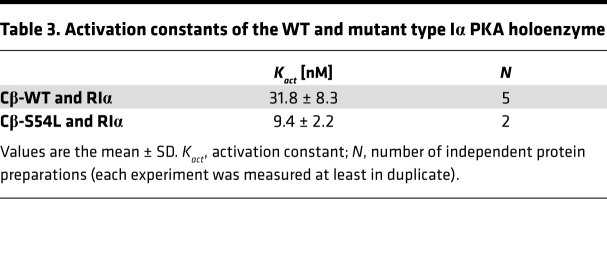

Table 3. Activation constants of the WT and mutant type Iα PKA holoenzyme.

PRKACB mutation S54L increases basal PKA activity.

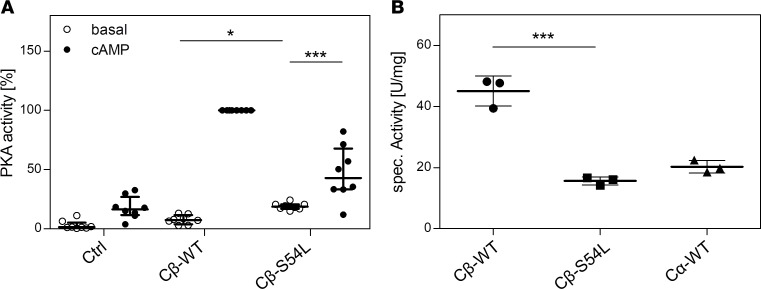

We then examined if this reduced holoenzyme stability observed with the mutant Cβ-S54L leads to higher basal PKA activity. For this, we coexpressed Cβ (Flag-tagged version of isoform 1) and RIα in HEK293 cells and checked the lysates for phosphotransferase activity. PKA activity was measured based on the phosphorylation of the synthetic substrate kemptide (LRRASLG) in cell lysates. Indeed, the basal PKA activity of Cβ-S54L was higher compared with WT (Figure 5A). However, after stimulation with cAMP, the activity of the mutant enzyme was lower. The lower phosphotransferase activity observed for the mutant was verified using purified recombinant PKA C subunits produced in E. coli. The Cβ-S54L mutant showed an almost 3-fold-reduced specific activity using kemptide as a substrate (Figure 5B). It has to be kept in mind that the specific activity observed for Cβ1-WT with more than 40 U/mg is more than twice as high as the activity determined for isoform 1 of Cα (Cα1). Thus, with about 16 U/mg the S54L mutant displays almost the same specific activity as the major isoform Cα1.

Figure 5. The mutation S54L causes increased phosphotransferase activity under basal conditions.

PKA activity was determined by quantifying the phosphorylation of a synthetic fluorescently labeled peptide (kemptide) in HEK293 cell lysates (A) or with unlabeled kemptide for purified recombinant catalytic subunits (B). In detail, (A) PKA activity was tested in lysates of HEK293 cells cotransfected with a combination of RIα and either WT or S54L Cβ1. Under basal conditions (no cAMP stimulation), the mutant holoenzyme showed higher PKA activity than the WT. In the presence of cAMP, maximal activity was lower for the mutant enzyme. Transfection of the empty pcDNA vector was used as control (Ctrl). Data from 4 independent experiments are represented as dot plots and were analyzed by ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. (B) PKA activity of purified recombinant RIα and catalytic subunits (Cβ-WT, Cβ-S54L, and Cα-WT) revealed an almost 3-fold-reduced phosphotransferase activity (15.6 ± 1.3 U/mg) for Cβ-S54L compared with Cβ-WT (45.1 ± 4.9 U/mg). The specific activity of the major isoform Cα1 was determined as a control (20.3 ± 2.0 U/mg). Data from 3 independent protein preparations are represented as dot plots and were analyzed by unpaired t test with Sidak’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001.

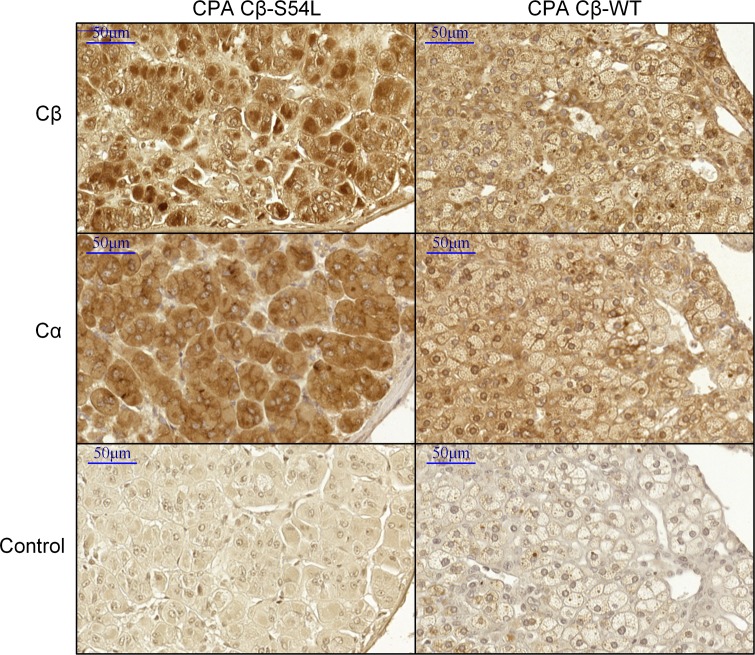

Immunostaining of PRKACB.

Immunostaining of Cβ on paraffin tumor sections of the CPA carrying the S54L PRKACB mutation showed an increased expression of Cβ in the nucleus compared with other adenomas, suggesting an activation of the PKA pathway in this tumor (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Cβ is localized in the nucleus in the Cβ-S54L adenoma.

Immunohistochemistry for Cα and Cβ in the S54L-mutated cortisol producing adenoma (CPA) and in a representative WT CPA (n = 2). A reinforcement of staining with regard to the nucleus is observed in the S54L-mutated adenoma compared with faint membrane (cytoplasmic and perinuclear) staining in the WT adenoma, whereas Cα localization was cytoplasmic in both adenomas. This nuclear localization of Cβ in the mutant adenoma suggests an activation of Cβ-S54L. Scale bars: 50 μm.

Discussion

Somatic mutations of PRKACA cause about 40% of CPAs, while mutations of the PRKAR1A and GNAS genes have been described more rarely. Here we describe what we believe to be a new mechanism of activation of the PKA pathway by a somatic activating mutation of PRKACB in a CPA responsible for a severe CS. The S54L PRKACB mutation leads to increased basal PKA activity in adrenocortical cells, as is the case with GNAS and PRKACA mutations (4, 9).

The particular function of Ser54 has been previously investigated (11). This residue is located at the tip of the G-loop, which is part of the small amino-terminal lobe of the C subunit. The G-loop is a conserved feature of all protein kinases and is critical for the binding of the cosubstrate ATP (adenosine triphosphate) and substrates (11, 12). Closing of the active site is associated with the movement of the G-loop and therefore necessary for stable substrate or inhibitor binding. Biochemical studies of Ser54 in Cα showed that the removal of its side chain (S54G mutant) did not result in alteration of kinase activity and sensitivity to R subunits (11). On the contrary, substitution of the serine with a proline led to a decrease of the phosphotransfer ability of the enzyme and to higher Km values for ATP and the peptide substrate kemptide. In addition, the S54P mutant exhibited a strongly reduced sensitivity to inhibition by type I R subunits (11). Leucine and proline are both amino acids with aliphatic side chains. It is also likely that the S54L mutation restricts the correct positioning of the G-loop. In contrast to serine, the bulky aliphatic side chain of leucine is sterically constrained and will likely hamper substrate (probably contributing to the lower maximal PKA activity) as well as pseudosubstrate binding.

The majority of studies on PKA function have been performed with Cα1. Human Cα1 and Cβ1 isoforms harbor 91% homology in their amino acid sequence (2). In vitro, their biochemical properties differ in the affinities for certain peptide substrates and the absence of inhibition of Cβ1 activity for high concentrations of substrates (13). Cβ-knockout mouse models suggest distinct roles for Cβ and Cα in neuronal development and hippocampal plasticity (14, 15). An involvement of Cβ in cancer has been demonstrated, with studies indicating that Cβ is playing either a role as a tumor suppressor gene (16) or as an oncogene (17, 18), depending on the cell model tested. It has been suggested that upregulation of PRKACB is critical for c-MYC–associated tumorigenesis (17, 19). Specific functions of Cβ versus Cα in the adrenal cortex, where Cβ is also expressed, have not been studied (20).

Constitutive activation of the PKA pathway leads to tumor development and endocrine overfunction, as observed in toxic thyroid adenoma and growth hormone–producing pituitary adenoma (21). CPA is the most frequent cause of ACTH-independent CS. Beyond the typical clinical picture, overt CS is associated with severe comorbidities and increased mortality (22, 23). Patients whose tumors harbor PRKACA mutations present at a younger age at diagnosis, higher cortisol levels, and, interestingly, smaller-size tumors than CPAs without mutations (24, 25). The present patient had as well an overt CS and a young age at diagnosis, but the size of the adenoma seems to be larger than described for PRKACA mutation (25). This could be consistent with an additional oncogenic function described for PRKACB. However, with a Weiss score of 1 the patient’s adenoma had no characteristics of malignancy. The Cancer Genome Atlas reveals alteration of PRKACB in various cancer (26) but not in adrenocortical carcinoma (27).

Recently, a triplication of PRKACB has been described in a patient with Carney complex who presented with a somatotroph adenoma, pigmented spots, and skin myxomas. This 19-year-old patient had not presented with adrenal disease at the time of publication. A mouse model, overexpressing the PRKACB gene, showed an increase of growth hormone levels at a young age (28). Thus, PRKACB may be considered as a candidate gene for tumors associated with endocrine hyperfunction. In sporadic somatotroph adenomas, sequencing of the PRKACB gene did not show any mutations but sequencing was limited to the region around codon 206 where the mutation hotspot of PRKACA in CPA is located (29).

In conclusion, PRKACB mutations lead to adrenal CS by the constitutive activation of the PKA pathway. This observation is the first demonstration to our knowledge of the involvement of a PRKACB sequence alteration in tumors. The data presented suggest that the Cβ subunit may have specific functions in the adrenal cortex. For the PKA research field, this study highlights the importance of the serine (Ser54) at the tip of the G-loop for kinase regulation and function.

Methods

Study approval.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Paris Ile de France III and patients’ written informed consent was obtained.

Genetic testing.

A total of 6 patients who had undergone surgery for CPA were included in the study. The tumor samples were obtained prospectively by the Cortico-medullo adrenal Tumors Endocrine Network tumor bank (30). DNA was extracted from fresh-frozen tissues and checked for signs of degradation as previously described (31). Exome DNA was captured using the SureSelectXT Human All Exon version 4 Kit (Agilent), following the manufacturer’s protocol, and then sequenced on a pair of SOLiD 5500xl flowchips (Supplemental Methods). The PRKACB coding and the flanking intronic sequences were amplified by PCR both in tumor DNA from 21 patients presenting with CPA. Both strands of the amplified products were directly sequenced with forward and reverse primers (Supplemental Table 2).

In silico modeling.

Somatic variants were evaluated by MutationTaster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/) (32), Polymorphism Phenotyping v2 algorithm tool (PolyPhen-2) (http://genetics.bwh-.harvard.edu/pph2) (33), and the SIFT (Sorting Tolerant From Intolerant) algorithm (http://sift.jcvi.org) (34) to predict the possible impact of the amino acid substitution on the structure and function of a human protein.

Patients.

The clinical data of the patient harboring the PRKACB mutations were collected retrospectively.

DNA constructs and cell culture.

The PRKACB sequence WT (NM_002731) and mutant were introduced into different expression vectors according to established protocols. More details are provided in the Supplemental Methods.

BRET assay.

HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with WT and mutant (S54L) GFP-Cβ (isoform 1) and the respective Renilla luciferase–tagged (RLuc-tagged) regulatory subunit using polyethyleneimine (25 kDa, Polysciences GmbH). The reporter proteins were expressed for 48 hours. For endpoint measurements, cells were washed with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS, Biowest) and incubated with 5 μM (final concentration) Coelenterazine 400A (BIOTREND Chem.) supplemented either with 50 μM forskolin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 100 μM IBMX (Sigma-Aldrich) or DPBS alone (untreated control) for 20 minutes. Data acquisition was performed on a POLARstar Omega microplate reader (dual emission optics, BMG Labtech) using filters at wavelengths 410 ± 80 nm (donor) and 515 ± 30 nm (acceptor). Emission values for nontransfected cells were subtracted for referencing. Control measurements with cells expressing RLuc8 alone were performed for each experiment. Mean values (± SD) were calculated from 3 independent measurements (each from 3–6 replicates).

For kinetic experiments, transfected cells were washed with DPBS and the reaction was started by the addition of 5 μM Coelenterazine 400A in DPBS. After 9 minutes, the cell-permeant precursor of 8-Br-cAMP (8-Br-cAMP-AM, B020, Biolog) was injected at a final concentration of 100 μM in DPBS supplemented with 5 μM Coelenterazine 400A using the reagent injector of the microplate reader.

Interaction analysis using SPR.

A Biacore T200 SPR instrument (GE Healthcare) was used for kinetic analysis of the interaction of PKA-Cβ WT and S54L with GST-PKA-RIα. For this, an anti-GST (glutathione S-transferase) antibody (Carl Roth) functionalized CM5 sensor chip (GE Healthcare) was used as described previously (35). GST-PKA-RIα was captured on this anti-GST antibody surface and several concentrations of either WT (0–8 nM) or S54L (0–32 nM) PKA-Cβ (isoform 1) were injected in running buffer (20 mM MOPS, pH 7, 150 mM NaCl, 50 μM EDTA, 1 mM ATP, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.01% P20) at a flow rate of 30 μl/min at 25°C for 300 seconds. Dissociation of the PKA-C–RIα complex was tested by switching to buffer without PKA-C for 300 seconds. Regeneration of the chip surface was performed by injecting 10 mM glycine (pH 1.9) for 30 seconds at 30 μl/min at the end of each measurement cycle. Binding of PKA-Cβ to GST-tagged PKIα was performed as described previously (35). Rate constants were determined by nonlinear curve fitting (global fit analysis) using the software T200 Evaluation 3.0 (GE Healthcare).

In order to test the cAMP sensitivity of WT and mutant PKA holoenzymes using SPR, GST-PKA-RIα was captured on the anti-GST antibody surface (30–40 response units [RU]) and 15 nM PKA-Cβ (WT or S54L) was injected in running buffer for 150 seconds to monitor association of the holoenzyme. Dissociation (buffer without PKA-C) was monitored for 250 seconds. To analyze cAMP-induced dissociation, running buffer containing cAMP at several concentrations (ranging from 0 nM to 320 nM) was injected for another 60 seconds. Surface regeneration was again performed by injecting 10 mM glycine (pH 1.9) for 30 seconds at 30 μl/min at the end of each measurement cycle. Dissociation rate constants of the cAMP-induced dissociation were determined using the software BIAevaluation 4.1.1.

In vitro PKA activity assay of purified proteins.

The expression and purification of recombinant PKA subunits are described in the Supplemental Methods. Specific activity in U/mg (μmol/min per mg) of purified proteins, recombinantly expressed in E. coli, were determined using a coupled spectrophotometric assay with kemptide (LRRASLG) according to Cook et al. (36). The same assay was used to determine apparent activation constants of WT and mutant holoenzymes. For this, holoenzymes were preformed by mixing PKA-RIα and the PKA-Cβ WT or S54L (isoform 1) in a molar ratio of 1:1.2 or 1:1.3, respectively. The sample was then transferred into a D-tube dialyzer tube (MWCO 6–8 kDa, Millipore) and dialyzed against buffer D (20 mM MOPS, pH 7, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM ATP, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol) at 4°C. In the kinase assay a final kinase concentration of either 10 nM (WT) or 20 nM (S54L) was used. Preformed holoenzymes were incubated with cAMP (0.1 nM to 100 μM) for 1 minute prior to measurement. All measurements were done at least in duplicate and with at least 2 independent holoenzyme preparations.

In vitro PKA activity assay with cell lysates.

All experiments were performed 48 hours after transfection. Cells were washed twice with PBS at room temperature, scraped from the plate, and resuspended in 300 μl lysis buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl, 2 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). The cells were lysed using an Ultra-turrax (IKA) for 20 seconds on ice. Then the samples were centrifuged at 50,000 g for 30 minutes at 4°C to remove membranes. To check for equal input of catalytic subunit for the PKA activity assay, expression of PKA subunits FLAG-Cβ, RIα, and RIIβ in cell lysates was determined by Western blot with specific antibodies (anti-FLAG [1:4,000], F7425, Sigma-Aldrich; anti–PKA RIα [1:1,000], 610609, BD Transduction Laboratories; anti–PKA RIIβ [1:1,000], 610625, BD Transduction Laboratories). PKA catalytic activity was measured with or without the addition of cAMP with the PepTag nonradioactive cAMP-dependent protein kinase assay (V5340, Promega) using kemptide, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Images of the gels were acquired with a gel documentation system (Herolab) and analyzed using ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij).

Immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry was performed on serial sections from paraffin-embedded adrenal adenoma (the Cβ-S54L mutated adenoma and 2 WT adenomas). The immunohistochemical procedure is described in details in Supplemental Methods.

Statistics.

All data are presented as the mean ± SD and P values were obtained by unpaired t test or ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons carried out using GraphPad Prism 6.

Author contributions

SE, JB, and CAS initiated and oversaw the study. SE, MJK, KB, GA, MRR, SF, WLR, and DA conducted experiments and acquired data. LG examined the patients and collected blood samples. SE and MJK wrote and JB, FWH, DC, and CAS edited the manuscript. All authors interpreted the data and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J. Bertherat’s lab is supported by the E-RARE program (ANR-13-RARE-008) and the PROMEX foundation. C.A. Stratakis’s lab is funded by the intramural research program of the NICHD (Z01 HD008920). F.W. Herberg’s lab is funded by BMBF e:Bio project (0316177 F), DFG (He 1818/10). D. Calebiro’s lab is funded by IZKF Würzburg (grant B281). S. Espiard and G. Assié are supported by INSERM. We thank I. Witzel and M. Hansch for excellent technical assistance and D. Bertinetti and M. Kaufholz for helpful discussions.

Version 1. 04/19/2018

Electronic publication

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Reference information: JCI Insight. 2018;3(8):e98296. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.98296.

Contributor Information

Stéphanie Espiard, Email: stephanie.espiard@live.fr.

Kerstin Bathon, Email: kerstin.bathon@uni-wuerzburg.de.

Guillaume Assié, Email: guillaume.assie@cch.aphp.fr.

Marthe Rizk-Rabin, Email: marthe.rizk@inserm.fr.

Simon Faillot, Email: s.faillot@gmail.com.

Windy Luscap-Rondof, Email: windy_lj@hotmail.com.

Daniel Abid, Email: daniel.abid@gmx.de.

Laurence Guignat, Email: laurence.guignat@aphp.fr.

Davide Calebiro, Email: davide.calebiro@toxi.uni-wuerzburg.de.

Friedrich W. Herberg, Email: herberg@uni-kassel.de.

References

- 1.Taylor SS, Zhang P, Steichen JM, Keshwani MM, Kornev AP. PKA: lessons learned after twenty years. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1834(7):1271–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skålhegg BS, Taskén K. Specificity in the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway. Differential expression, regulation, and subcellular localization of subunits of PKA. Front Biosci. 1997;2:d331–d342. doi: 10.2741/A195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Espiard S, Bertherat J. The genetics of adrenocortical tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2015;44(2):311–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beuschlein F, et al. Constitutive activation of PKA catalytic subunit in adrenal Cushing’s syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(11):1019–1028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao Y, et al. Activating hotspot L205R mutation in PRKACA and adrenal Cushing’s syndrome. Science. 2014;344(6186):913–917. doi: 10.1126/science.1249480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato Y, et al. Recurrent somatic mutations underlie corticotropin-independent Cushing’s syndrome. Science. 2014;344(6186):917–920. doi: 10.1126/science.1252328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goh G, et al. Recurrent activating mutation in PRKACA in cortisol-producing adrenal tumors. Nat Genet. 2014;46(6):613–617. doi: 10.1038/ng.2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calebiro D, et al. PKA catalytic subunit mutations in adrenocortical Cushing’s adenoma impair association with the regulatory subunit. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5680. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ronchi CL, et al. Genetic landscape of sporadic unilateral adrenocortical adenomas without PRKACA p.Leu206Arg mutation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(9):3526–3538. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prinz A, Diskar M, Erlbruch A, Herberg FW. Novel, isotype-specific sensors for protein kinase A subunit interaction based on bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) Cell Signal. 2006;18(10):1616–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aimes RT, Hemmer W, Taylor SS. Serine-53 at the tip of the glycine-rich loop of cAMP-dependent protein kinase: role in catalysis, P-site specificity, and interaction with inhibitors. Biochemistry. 2000;39(28):8325–8332. doi: 10.1021/bi992800w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bossemeyer D. The glycine-rich sequence of protein kinases: a multifunctional element. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19(5):201–205. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gamm DM, Baude EJ, Uhler MD. The major catalytic subunit isoforms of cAMP-dependent protein kinase have distinct biochemical properties in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(26):15736–15742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang Y, Roelink H, McKnight GS. Protein kinase A deficiency causes axially localized neural tube defects in mice. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(22):19889–19896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111412200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qi M, et al. Impaired hippocampal plasticity in mice lacking the Cbeta1 catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(4):1571–1576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, Gao Y, Tian Y, Tian DL. PRKACB is downregulated in non-small cell lung cancer and exogenous PRKACB inhibits proliferation and invasion of LTEP-A2 cells. Oncol Lett. 2013;5(6):1803–1808. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu KJ, Mattioli M, Morse HC, Dalla-Favera R. c-MYC activates protein kinase A (PKA) by direct transcriptional activation of the PKA catalytic subunit beta (PKA-Cbeta) gene. Oncogene. 2002;21(51):7872–7882. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ihara T, et al. An in vivo screening system to identify tumorigenic genes. Oncogene. 2017;36(14):2023–2029. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Padmanabhan A, Li X, Bieberich CJ. Protein kinase A regulates MYC protein through transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms in a catalytic subunit isoform-specific manner. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(20):14158–14169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.432377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shuntoh H, Sakamoto N, Matsuyama S, Saitoh M, Tanaka C. Molecular structure of the C beta catalytic subunit of rat cAMP-dependent protein kinase and differential expression of C alpha and C beta isoforms in rat tissues and cultured cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1131(2):175–180. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(92)90073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Hayre M, et al. The emerging mutational landscape of G proteins and G-protein-coupled receptors in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(6):412–424. doi: 10.1038/nrc3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calebiro D, Di Dalmazi G, Bathon K, Ronchi CL, Beuschlein F. cAMP signaling in cortisol-producing adrenal adenoma. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;173(4):M99–106. doi: 10.1530/EJE-15-0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lodish M, Stratakis CA. A genetic and molecular update on adrenocortical causes of Cushing syndrome. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12(5):255–262. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thiel A, et al. PRKACA mutations in cortisol-producing adenomas and adrenal hyperplasia: a single-center study of 60 cases. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;172(6):677–685. doi: 10.1530/EJE-14-1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Dalmazi G, et al. Novel somatic mutations in the catalytic subunit of the protein kinase A as a cause of adrenal Cushing’s syndrome: a European multicentric study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(10):E2093–E2100. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, et al. The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer analysis project. Nat Genet. 2013;45(10):1113–1120. doi: 10.1038/ng.2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng S, et al. Comprehensive pan-genomic characterization of adrenocortical carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2016;30(2):363. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forlino A, et al. PRKACB and Carney complex. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(11):1065–1067. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1309730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larkin SJ, et al. Sequence analysis of the catalytic subunit of PKA in somatotroph adenomas. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;171(6):705–710. doi: 10.1530/EJE-14-0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gicquel C, et al. Molecular markers and long-term recurrences in a large cohort of patients with sporadic adrenocortical tumors. Cancer Res. 2001;61(18):6762–6767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Libé R, et al. Phosphodiesterase 11A (PDE11A) and genetic predisposition to adrenocortical tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(12):4016–4024. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwarz JM, Cooper DN, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster2: mutation prediction for the deep-sequencing age. Nat Methods. 2014;11(4):361–362. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adzhubei IA, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7(4):248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: Predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knape MJ, et al. Divalent metal ions Mg²+ and Ca2+ have distinct effects on protein kinase A activity and regulation. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10(10):2303–2315. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cook PF, Neville ME, Vrana KE, Hartl FT, Roskoski R. Adenosine cyclic 3′,5′-monophosphate dependent protein kinase: kinetic mechanism for the bovine skeletal muscle catalytic subunit. Biochemistry. 1982;21(23):5794–5799. doi: 10.1021/bi00266a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.