Abstract

Objective

We evaluated outcomes of infants born regionally with end stage renal disease (ESRD), and those within our broader catchment area referred for dialysis.

Study Design

We screened deaths at 5 regional referral hospitals, identifying infants with ESRD who did not survive to transfer for dialysis. We also screened all infants <8 weeks old seen at our institution over a 7-year period with ESRD referred for dialysis. We evaluated factors associated with survival to dialysis and transplant.

Results

We identified 14 infants from regional hospitals who died prior to transfer and 12 infants at our institution who were dialyzed. Because of the large burden of lethal co-morbidities in our regional referral centers, overall survival was low, with 73% dying at birth hospitals. Amongst dialyzed infants, 42% survived to transplant.

Conclusion

This study is unusual in reporting survival of infants with ESRD including those not referred for dialysis, which yields an expectedly lower survival rate than reported by dialysis registries.

Keywords: Neonatal intensive care, infant, neonate, nephrology, renal failure

Introduction

Advances in infant dialysis in recent decades have led to improvements in the survival of newborns with end stage renal disease (ESRD)1, 2, 3; however, infants born with ESRD requiring initiation of renal replacement therapy within the first few weeks of life remain challenging to manage. Historically, there have been differing opinions among providers regarding whether and when to initiate infant dialysis,4 and recent surveys continue to indicate varying opinions regarding the initiation of dialysis versus comfort care for infants < 1 month of age.5

Recent studies of infants who initiated dialysis between birth and 2 years of age have shown survival rates of 50-80%, with over 50% of infants surviving to renal transplant.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 However, many of these studies evaluate the survival of infants who are enrolled in registries after successfully initiating dialysis,9, 12 and are therefore prone to selection bias, as infants who have complicated early life courses and do not survive to dialysis initiation may not be included. There are few data assessing the overall survival of infants born with presumed ESRD, including those who are not referred for further management, those who do not survive to initiation of dialysis, and those who do not survive early dialysis.

We sought to understand this more encompassing outcome of newborns with ESRD on a population rather than registry level given the potential for selection bias in registry data. Newborns referred to our institution for dialysis are admitted to our Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) from two categories of sources, “regional” referrals from a set of five local NICU’s who consistently transfer patients to us for management of renal disease, and a broader set of hospitals from which we receive transfers more sporadically. We use the term “catchment area” referrals to describe the combination of regional and broader based referrals.

The objective of this study was to determine the survival to transplant of infants 1) born regionally with ESRD whether they died at their birth hospital or survived to transfer for dialysis and 2) within our catchment area who were transferred to our institution for dialysis. In addition, we sought to assess factors associated with survival to dialysis initiation and survival to renal transplant.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, we screened NICU records between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2014 at 5 regional level III NICUs. We reviewed lists of all infant deaths to identify those infants who died with pulmonary hypoplasia or renal failure and evaluated these patients in greater detail to determine whether they met diagnostic criteria for ESRD. In contrast to our regional referrals, for our entire catchment area, we could not feasibly screen all deaths. Yet, in order to best understand the outcomes of infants in our dialysis program, we did include patients referred from our entire catchment area in our analysis of dialysis outcomes.

Thus, we screened all infants admitted during this same time period to the NICU at a large, urban, free standing children’s hospital that is a referral center for infant dialysis with an ICD-9 code for stage 5 chronic kidney disease (585.5), end stage renal disease (585.6), pulmonary hypoplasia (748.5), renal aplasia or dysplasia (753.15), renal failure, not otherwise specified (586), or who had a CPT code for peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis. We also reviewed lists of active and past dialysis patients as well as NICU records of infants requiring dialysis.

We excluded infants who developed severe acute kidney injury and subsequent ESRD secondary to non-renal conditions including congenital heart disease, sepsis, and extreme prematurity. We also excluded infants with primary renal disease who initiated acute dialysis but had improvement of renal function, permitting discontinuation of dialysis prior to hospital discharge; these infants did not meet diagnostic criteria for ESRD.

Among infants with ESRD, defined as infants who required chronic dialysis initiation within the first 8 weeks of life or who died of complications related to severe renal disease, we collected data by chart review regarding birth history, hospital course, and cause of death if relevant. For those infants who survived to dialysis initiation, we recorded the fluid and nutritional status prior to dialysis initiation, timing of dialysis catheter placement and dialysis initiation, dialysis complications including peritonitis, catheter leakage, or dialysis modality change, and whether the infant ultimately received a renal transplant.

This study was approved by the IRB at all hospitals in which chart review was indicated, namely Boston Children’s Hospital, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and South Shore Hospital.

Results

We identified 14 infants from 5 regional referral institutions who were born with ESRD and did not survive to transfer. The included infants came from 3 institutions; 2 of the referral hospitals reported no infant mortalities related to ESRD during the study period.

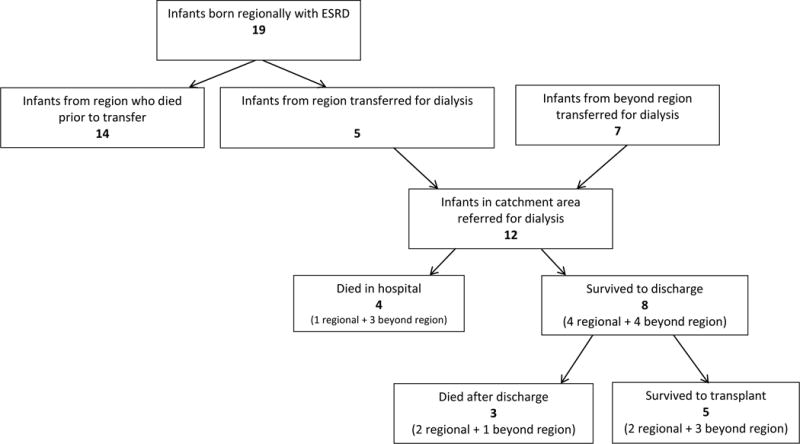

We identified 12 additional infants during the 7-year study period who were started on dialysis and ultimately met criteria for inclusion. These 12 infants included 5 from the regional centers and 7 from our broader catchment area. Of these 12, 8 survived to discharge home and 5 survived to renal transplant (Figure 1), yielding an overall survival rate of 67% from dialysis to discharge and 42% from dialysis to transplant.

Figure 1.

Patient Flow Diagram

Adding the 5 patients from our regional referral centers who survived to transfer and the 14 who did not survive, yields a total of 19 patients born within our region with ESRD. Based on Massachusetts state birth data of the number of infants born at the 5 referral hospitals,13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 we estimate that the incidence of ESRD among infants from our referral institutions was 1.4 infants/10,000 live births during the study period. Of the 5 infants who survived to transfer, 4 were discharged home and 2 survived to transplant yielding an overall regional survival rate of 21% from birth to discharge and 10% from birth to transplant, with 73% of deaths occurring prior to transfer.

By combining the 12 patients referred for dialysis and the additional 14 regional patients who died prior to transfer we analyzed a total of 26 infants born in our catchment area with ESRD. The most common causes of ESRD were obstructive uropathy and cystic kidney disease (Table 1). In 92%, renal disease was diagnosed prenatally. Of the 14 infants who expired at regional hospitals, 93% died from respiratory failure. Infants who died were smaller than those who survived to transfer [median birthweight 2062 grams, (IQR 1418 grams) versus 2960 grams (IQR 2555 grams)]and had a lower median gestational age (35.3 weeks, IQR 32, versus 36.1 weeks, IQR 34.5). Extrarenal congenital anomalies, including cardiac, urologic and other anomalies, were more common in infants who died prior to transfer (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of infants enrolled in study [n(%) unless otherwise specified]

| Infant characteristics | Regional patients who died prior to transfer | Catchment area (regional and broader based referrals) patients who survived to transfer | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=14) | Died prior to discharge (n=4) | Discharged (n=8) | Total (n=12) | |

| Median gestational age in weeks (IQR) | 35.3 (5.6) | 34 (2.7) | 36.3 (1.2) | 36.1 (2.3) |

| Male gender | 10 (71%) | 2 (50%) | 6 (75%) | 8 (67%) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Black | – | – | 1 (12.5%) | 1 (8%) |

| White | 2 (14%) | 2 (50%) | 4 (50%) | 6 (50%) |

| Hispanic | – | 1 (25%) | 2 (25%) | 3 (25%) |

| Asian/Pacific islander | – | – | 1 (12.5%) | 1 (8%) |

| Other/unspecified | 12 (86%) | 1 (25%) | – | 1 (8%) |

| Median birth weight in grams (IQR) | 2062 (1420) | 2655 (912) | 3000 (1190) | 2960 (895) |

| Prenatal diagnosis, n (%) | 14 (100%) | 3 (75%) | 7 (87.5%) | 10 (83%) |

| Etiology of renal disease | ||||

| Renal dysplasia/ MCDK | 8 (57%) | – | – | – |

| Obstructive uropathy | 4 (29%) | – | 3 (37.5%) | 3 (25%) |

| Cystic kidney disease | 2 (14%) | 1 (25%) | 3 (37.5%) | 4 (33%) |

| Nephronophthisis | 2 (50%) | 2 (17%) | ||

| Congenital Nephrotic Syndrome | 2 (25%) | 2 (17%) | ||

| Other | 1 (25%) | 1 (8%) | ||

| Pulmonary Involvement | ||||

| Required positive pressure ventilation | 14 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 6 (85%) | 10 (83%) |

| Days of invasive ventilation, median (IQR) | 1 (4) | 36 (57) | 16 (5) | 17.5 (20) |

| Days of non-invasive ventilation, median (IQR) | – | 15 (45) | 11 (3) | 11.5 (24) |

| Required a chest tube | 9 (64%) | 1 (25%) | 3 (42%) | 4 (33%) |

| Extra renal congenital anomalies | ||||

| VACTERL | 2 (14%) | – | 1 (12%) | 1 (8%) |

| Cardiac anomalies | 5 (36%) | – | 1 (12%) | 1 (8%) |

| Urologic anomalies | 1 (7%) | – | 3 (38%) | 3 (25%) |

| Other anomalies | 6 (43%) | 2 (50%) | 3 (38%) | 5 (42%) |

| Cause of death | ||||

| Respiratory failure | 13 (93%) | 1 | – | 1 (8%) |

| Sepsis | 1 (7%) | 2 | – | 2 (16%) |

| Unknown | – | 1 | – | 1 (8%) |

All infants who were transferred initiated dialysis. The majority of infants were started on peritoneal dialysis (PD). Among infants who survived to discharge, dialysis catheters were placed at an older age and the interval between dialysis catheter placement and dialysis initiation was longer compared with infants who did not survive to discharge (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of infants initiated on dialysis for management of ESRD [n(%), unless otherwise specified]

| Infant characteristics | Died prior to discharge n=4 |

Survived to discharge n=8 |

|---|---|---|

| Days old at transfer, median (IQR) | 4 (185) | 21 (47) |

| Oliguric at the time of transfer | 4 (100%) | 4 (50%) |

| Dialysis | ||

| Days old at catheter placement, median (IQR) | 2.5 (6) | 25 (42) |

| Peritoneal placement of initial catheter | 3 (75%) | 7 (87.5%) |

| Days from catheter placement to initiation of peritoneal dialysis, median (IQR) | 7 (4) | 11.5 (6) |

| Edematous at the time of dialysis initiation | 3 (75%) | 5 (62%) |

| Days from catheter placement to full dialysis, median (IQR) | 11.5 (9) | 14 (7.5) |

| Days from catheter placement to cycler, median (IQR) | 16 (14)* | 19.5 (12) |

| Dialysis complications | ||

| Peritonitis | 2 (50%) | 3 (37.5%) |

| Catheter leakage | 3 (75%) | 2 (25%) |

| Dialysis modality change | 3 (75%) | 5 (37.5%) |

| Catheter replacement | 2 (50%) | 2 (25%) |

| Non-dialysis complications | ||

| Reintubation | 3 (75%) | 3 (37.5%) |

| Sepsis | 4 (100%) | 2 (25%) |

| Seizure | 1 (25%) | 2 (25%) |

| Bleeding | 1 (25%) | 0 |

| Hypertension | 3 (75%) | 3 (37.5%) |

| Vasopressor requirement | 1 (25%) | 4 (50%) |

| Other | 2 (50%) | 5 (62.5%) |

| Nutrition | ||

| Days old when reached goal caloric intake, median (IQR) | 23.5 (31) | 21 (19) |

| Discharged with NG/Gtube | n/a | 7 (87.5%) |

| Weight gain in gms from birth weight prior to dialysis, median (IQR) | 540 (622.5) | 622.5 (515) |

| Weight in gms at discharge/death, median (IQR) | 3170 (659) | 4160 (1260) |

| Days old at discharge/death, median (IQR) | 68.5 (35) | 81.5 (40.5) |

| Neurologic Evaluation | ||

| Head imaging obtained | 3 (75%) | 6 (75%) |

| EEG obtained | 2 (50%) | 4 (n=7) |

| Neurology consultation obtained | 1 (25%) | 4 (50%) |

| Neurologic diagnoses | ||

| Stroke | 0 | 1 (12.5%) |

| Seizure | 1 (25%) | 4 (50%) |

(n=2; 2 infants only received manual peritoneal dialysis)

Complications were common after dialysis initiation, with over 40% of infants developing peritonitis or catheter leakage, and 67% requiring dialysis modality change. One third of infants required replacement of their peritoneal catheter. Infants who experienced peritoneal dialysis catheter leakage had a shorter median time from catheter placement to dialysis initiation [7 days (IQR 4)] than infants who did not experience catheter leakage [11 days (IQR 4)]. Non-dialysis complications were also common, with 50% of infants requiring reintubation after initial extubation, or developing sepsis (Table 2). Among the 4 infants who did not survive dialysis initiation, dialysis withdrawal or failure was not the primary cause of death, though dialysis complications including infection related to dialysis catheters did contribute to mortality in some cases.

Though it was difficult to discern the contribution of weight gain attributable to lean body mass gain versus edema, the median weight gain prior to starting dialysis was 622 grams (IQR 515) among infants who survived and 540 grams (IQR 623) among those who died. Based on review of the physical exam in the medical record, infants who survived were less likely (62%) than those who died (75%) to have at least mild edema documented at the time of dialysis initiation.

Regarding nutrition, all infants reached goal feeds, but only 4 infants were receiving their goal feeds at the time of dialysis initiation (data not shown). Goal feeds were reached earlier [median of 21 days (IQR 19)] of life for infants who survived to discharge than for infants who did not [23.5 day (IQR 31)]. Of the children who survived to discharge, almost all went home with either a nasogastric tube or a gastrostomy tube (Table 2).

Of the 8 infants who survived to initial hospital discharge, 5 ultimately received renal transplant. The 3 infants who did not receive renal transplant died after their initial hospitalization (Table 3). One infant died in the hospital and the other 2 died at home. The cause of death of the infant who died in the hospital was typhlitis; the cause of death for the other two is unknown. Eighty eight percent of infants who survived to hospital discharge required at least one hospital readmission prior to their transplant or death.

Table 3.

Characteristics of infants who survived to initial hospital discharge with diagnosis of ESRD

| Characteristics | Infants discharged on dialysis, n (%) n=8 |

| Home dialysis complications | |

| Peritonitis | 3 (37.5%) |

| Readmission | 7 (88%) |

| Infant died after discharge | 3 (37.5%) |

| Infant received a transplant | 5 (62.5%) |

Discussion

In this regional study of infants born with ESRD, fewer referred for care survived to transplant than would be expected based on widely quoted data from dialysis registries, which generally do not include infants who die prior to being established on dialysis.11, 12 The small sample size of this study markedly limits generalizability and restricts us to descriptive rather than statistical analysis.

We found that survival to hospital discharge among infants with ESRD who were started on dialysis was 67% and survival to renal transplant of infants who were started on dialysis was 42%; 63% of those infants who survived to discharge ultimately received a renal transplant. This survival is lower than that reported in larger registries of infants with ESRD; survival of infants initiated on dialysis in the North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies (NAPRTCS) database was 89% for those started on dialysis at less than 1 month of age and 92% for those initiated between 1 and 24 months of age.12 A similar registry study from Canada found somewhat lower survival of infants with ESRD than the NAPRTCS study, though survival was still higher than in our study.9 Some of this difference in survival may be related to the nature of enrollment in registry studies, in which infants may not be enrolled unless successfully initiated on ambulatory dialysis.2, 12 The voluntary basis of enrollment in these registries creates a propensity for better outcome statistics than a population based analysis.

While registries report higher survival rates, other single center studies of infants with ESRD have shown similar survival to our study. A study of infants started on dialysis before 28 days of life reported a 52% one year survival and a 70.5% survival to renal transplant among patients who survived to initial hospital discharge,6 findings similar to our results. Another single center study reported 75% survival of children started on dialysis under 1 year of age, however many of the infants included in this study were older at the start of dialysis than the infants in our study.7

While a number of single center studies and registry reviews have evaluated infants started on dialysis, data regarding the number of infants who do not survive to transfer for further nephrology care or dialysis initiation are sparse. One review of children diagnosed with ESRD prior to the age of 2 years in Britain and Ireland found that 8% of children included in the study were not treated for ESRD; of infants who were started on dialysis, 7% had medical technology withdrawn, and an additional 20% of children started on dialysis died of other causes.19 There was a trend towards higher mortality in children started on dialysis prior to 2 months of age.19 The lower survival of infants with ESRD that we observed when evaluating births across a number of large regional hospitals parallels these findings and highlights the importance of further evaluating overall survival of infants with ESRD.

In our study, there was a trend towards increased survival in infants who were of older gestational age at the time of delivery. Infants who survived had higher birth weights than those who did not survive. Oliguria and earlier dialysis catheter placement were risk factors for mortality. Infants who did not survive to transfer were also more likely to have cardiac anomalies (36% vs 8%) as well as other urologic anomalies (36% versus 8%). Severe pulmonary disease was present in all of the infants who died.

Complications of dialysis, including peritonitis and catheter leak, were common in our study, findings similar to larger reviews of peritoneal catheter placement, which have shown that peritoneal dialysis catheter placement prior to one year of age is significantly associated with hernia, catheter leak, and mortality.20 Nearly 90% of infants who survived to hospital discharge required readmission. Achieving target nutrition was significantly delayed in infants referred for dialysis initiation. Furthermore, 88% of infants went home with gastrostomy of NG feeds, underscoring the medical burden facing infants with ESRD.

Efforts are currently underway to introduce peritoneal dialysis bundles and implement standardized pediatric peritoneal dialysis care practices nationally to substantially reduce catheter-related infections, including peritonitis.21 These initiatives have led to a reduction of peritonitis rates by optimizing the quality of care provided to children with ESRD and thereby improve the outcomes of this vulnerable population.22

The finding that the vast majority of patients with ESRD are diagnosed prenatally suggests a prominent role for the nephrologist in antenatal assessment and counseling. Facilitating the delivery of these pregnancies at a site with nephrology expertise including infant renal replacement therapy provides an opportunity to minimize transports and optimize care.

There are a number of limitations to this study. Our population of patients with ESRD was small, even when expanded to include patients from our broader catchment area. In addition, within our region, some infants who died in the delivery room had minimal documentation; it is possible that some of these infants were born with severe renal disease, in which case they would have been missed. We also could not evaluate the number of fetuses with severe renal anomalies who did not survive to birth. It is possible that infants within our region could have been transferred to other area hospitals for further management, though the vast majority of infant dialysis initiation regionally occurs at out institution. We did not obtain maternal data and therefore could not analyze contributions to morbidity and mortality of obstetric factors such as oligohydramnios and induction of labor. Finally, this study was based on chart review, and some participant characteristics, such as relative contributors to weight gain of fluid overload versus gain in lean body mass, were difficult to ascertain.

Conclusion

Overall survival of infants born with ESRD was lower in this study than in many reported analyses of infants with ESRD because we included infants who died prior to transfer for dialysis, a typically under-reported segment of the ESRD population. When looking only at patients referred for dialysis, our outcomes were lower than registry based results, but similar to other single center results, a difference likely attributable to the voluntary enrollment in registries making them subject to selection bias. Our findings must be interpreted in light of the small sample size. The population of infants who do not survive to transfer warrants further investigation to more fully understand predictors of survival among infants with ESRD. Clarifying that registry based outcome data is intended to describe those infants who survive to dialysis and not those born with lethal co-morbidities may be helpful when counseling families.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Terri Gorman of St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center and Dr. Alan Fujii of Boston Medical Center for their assistance with reviewing data at their respective facilities. We would like to thank Ashley Park for her assistance with manuscript editing and formatting.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was approved by the Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board.

References

- 1.Neu AM, Warady BA. Dialysis and renal transplantation in infants with irreversible renal failure. Adv Ren Replace Ther. 1996;3(1):48–59. doi: 10.1016/s1073-4449(96)80040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carey WA, Martz KL, Warady BA. Outcome of Patients Initiating Chronic Peritoneal Dialysis During the First Year of Life. Pediatrics. 2015;136(3):e615–622. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitsnefes MM, Laskin BL, Dahhou M, Zhang X, Foster BJ. Mortality risk among children initially treated with dialysis for end-stage kidney disease, 1990-2010. JAMA. 2013;309(18):1921–1929. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.4208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geary DF. Attitudes of pediatric nephrologists to management of end-stage renal disease in infants. J Pediatr. 1998;133(1):154–156. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teh JC, Frieling ML, Sienna JL, Geary DF. Attitudes of caregivers to management of end-stage renal disease in infants. Perit Dial Int. 2011;31(4):459–465. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2009.00265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rheault MN, Rajpal J, Chavers B, Nevins TE. Outcomes of infants <28 days old treated with peritoneal dialysis for end-stage renal disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24(10):2035–2039. doi: 10.1007/s00467-009-1234-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ledermann SE, Scanes ME, Fernando ON, Duffy PG, Madden SJ, Trompeter RS. Long-term outcome of peritoneal dialysis in infants. J Pediatr. 2000;136(1):24–29. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(00)90044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hijazi R, Abitbol CL, Chandar J, Seeherunvong W, Freundlich M, Zilleruelo G. Twenty-five years of infant dialysis: a single center experience. J Pediatr. 2009;155(1):111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexander RT, Foster BJ, Tonelli MA, Soo A, Nettel-Aguirre A, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. Survival and transplantation outcomes of children less than 2 years of age with end-stage renal disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27(10):1975–1983. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Stralen KJ, Borzych-Duzalka D, Hataya H, Kennedy SE, Jager KJ, Verrina E, et al. Survival and clinical outcomes of children starting renal replacement therapy in the neonatal period. Kidney Int. 2014;86(1):168–174. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wedekin M, Ehrich JH, Offner G, Pape L. Renal replacement therapy in infants with chronic renal failure in the first year of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(1):18–23. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03670609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carey WA, Talley LI, Sehring SA, Jaskula JM, Mathias RS. Outcomes of dialysis initiated during the neonatal period for treatment of end-stage renal disease: a North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies special analysis. Pediatrics. 2007;119(2):e468–473. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Health MDoP, editor. Massachusetts Births 2014. Boston, MA: Executive Office of Health and Human Services; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Health MDoP, editor. Massachusetts Births 2013. Boston, MA: Executive Office of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Health MDo, editor. Massachusetts Births 2011 and 2012. Boston, MA: Executive Office of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Health MDo, editor. Massachusetts Births, 2010. Boston, MA: Executive Office of Health and Human Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Health MDo, editor. Massachusetts Births 2009. Boston, MA: Executive Office of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Health MDo, editor. Massachusetts Births 2008. Boston, MA: Executive Office of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coulthard MG, Crosier J. Outcome of reaching end stage renal failure in children under 2 years of age. Arch Dis Child. 2002;87(6):511–517. doi: 10.1136/adc.87.6.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phan J, Stanford S, Zaritsky JJ, DeUgarte DA. Risk factors for morbidity and mortality in pediatric patients with peritoneal dialysis catheters. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48(1):197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neu AM, Miller MR, Stuart J, Lawlor J, Richardson T, Martz K, et al. Design of the standardizing care to improve outcomes in pediatric end stage renal disease collaborative. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29(9):1477–1484. doi: 10.1007/s00467-014-2891-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neu AM, Richardson T, Lawlor J, Stuart J, Newland J, McAfee N, et al. Implementation of standardized follow-up care significantly reduces peritonitis in children on chronic peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int. 2016;89(6):1346–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]