Abstract

Purpose of the study

The incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI) with a poor prognosis in the elderly has been increasing each year. This study aimed to investigate the clinical characteristics of and risk factors for death from AKI in the elderly and help improve prognosis.

Study design

This study was a retrospective cohort study based on data from adult patients (≥18 years old) admitted to 15 hospitals in China between 1 January 2009 and 31 December 2011. The characteristics of AKI in the elderly were compared with those in younger patients.

Results

In elderly patients with AKI, rates of hypertension, cardiovascular disease and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) were higher than in younger patients (44.2% vs 31.2%, 16.1% vs 4.6% and 20.9% vs 16.9%, respectively), the length of ICU stay was longer (3.8 days vs 2.7 days, P=0.019) and renal biopsy (1.0% vs 7.13%, P<0.001) and dialysis (9.6% vs 19.2%, P<0.001) were performed less. Hospital-acquired (HA) AKI was more common than community-acquired (CA) AKI (60.3% vs 39.7%), while the most common cause of AKI was pre-renal (53.5%). Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that age (OR 1.041, 95% CI 1.023 to 1.059), cardiovascular disease (OR 1.980, 95% CI 1.402 to 2.797), cancer (OR 2.302, 95% CI 1.654 to 3.203), MODS (OR 3.023, 95% CI 1.627 to 5.620) and mechanical ventilation (OR 2.408, 95% CI 1.187 to 4.887) were significant risk factors for death.

Conclusions

HA-AKI and pre-renal AKI were more common in the elderly. Age, cardiovascular disease, cancer, MODS and mechanical ventilation were independent risk factors for death in the elderly with AKI.

Keywords: acute renal failure, aki, elderly, clinical characteristics, mortality risk factors

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is common in hospitalised adults and is associated with significantly higher in-hospital mortality and resource usage.1 An association between AKI and the elderly has long been recognised,2 with AKI being more common in the elderly than in other age groups. The incidence of AKI in the elderly has been increasing annually, accompanied by a higher death rate than in younger patients, along with a poor prognosis and a lack of effective drugs. AKI in the elderly has become a serious public health problem. However, in our country, only a few multicentre studies on AKI in the elderly have been conducted. Therefore, exploring the characteristics of and risk factors for death in the elderly with AKI may help improve the current poor prognosis of this condition.

Material and methods

Study design

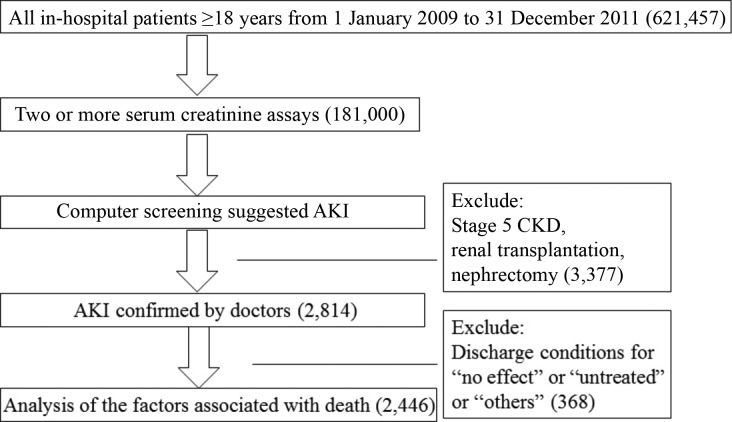

A multicentre, retrospective cohort of patients with AKI (aged ≥18 years old) in 15 tertiary hospitals in China (the distribution of the 15 hospitals is given in online supplementary table 1) from 1 January 2009 to 31 December 2011 was recruited. The inclusion criteria were as follows: age ≥18 years, and initial identification of AKI according to Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria and expanded criteria. Patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD), those receiving maintenance dialysis, those who had received a kidney transplant, and those who had undergone nephrectomy were excluded. The AKI patient screening process is shown in figure 1. The Medical Ethics Committee of the Chinese PLA General Hospital approved the study protocol and waived patient consent.

Figure 1.

Screening of AKI patients. AKI, acute kidney injury; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

postgradmedj-2017-135455supp001.docx (15.3KB, docx)

Data sources

Data including patient age, gender, admission and discharge dates, length of stay (LOS), inpatient ward, serum creatinine (SCr) values and test date, medical history, diagnosis, invasive procedures and surgeries, the number of failed organs in each patient, all-cause in-hospital death and total cost were collected from electronic medical records and laboratory databases. All AKI medical records were checked by trained nephrologists.

Definition of AKI

The criteria for identifying AKI included the 2012 KDIGO AKI definition and expanded criteria. AKI was identified on the basis of a 0.3 mg/dL increase in SCr within 48 hours or a 50% increase in SCr from baseline within 7 days according to the KDIGO criteria.3 AKI expanded criteria included a 50% increase or decrease in SCr during the hospital stay relative to the SCr value at admission as baseline for those who did not have a repeat SCr assay within 7 days or who were recovering from AKI.4 5

AKI stage was determined by the peak SCr level after AKI onset.3 AKI was classified as community-acquired AKI (CA-AKI) or hospital-acquired AKI (HA-AKI). When AKI was diagnosed within 48 hours of admission to hospital or in the community, it was defined as CA-AKI.3 However, when AKI occurred 48 hours after admission to hospital or did not meet the CA-AKI criteria, it was defined as HA-AKI.3

The causes of AKI were classified as pre-renal, renal and post-renal, as determined by nephrologists. If AKI patients had both pre-renal and renal causes of AKI, it was classified as renal. If a post-renal cause was identified with pre-renal and/or renal causes, AKI was classified as post-renal.6 7

MODS was diagnosed if there was dysfunction of two or more major organs according to the American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference.8 Cardiovascular failure was defined as characterised mean arterial blood pressure <60 mmHg and the use of vasoactive drugs to maintain blood pressure. Respiratory failure was defined as a PaO2 value <60 mmHg and/or a PaCO2 value >50 mmHg and the need for mechanical ventilation. Central nervous system failure was defined as Glasgow Coma Scale scores <7. Liver dysfunction was defined as total serum bilirubin >2 mg/dL and alanine amino transaminase more than twice the normal level.9 10

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as the mean±SD or median (IQR). Categorical variables were expressed as n (%). One-way ANOVA or the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for continuous variables. The χ² test was used for categorical variables. Logistic regression analysis was used to explore the risk factors for death from AKI in the elderly. All P values were two-sided, and P<0.05 was considered significant. Analyses were performed with IBM SPSS 22.0 software (SPSS Institute, IBM, USA).

Results

Detection of and rate of death from AKI in the elderly

AKI was detected in 1.61% of the elderly in hospital, and the death rate was 16.7% (255/1525). Both values were higher than in younger AKI patients (P<0.05) (table 1).

Table 1.

Detection of and rate of death from acute kidney injury (AKI)

| Total | Elderly patients | Younger patients | P value | |

| In-hospital patients (n) | 621 457 | 308 982 | 312 475 | |

| Two or more serum creatinine assays (n) | 181 000 (29.1%) | 94 757 (30.7%) | 86 243 (27.6%) | <0.001 |

| AKI patients (n) | 2814 | 1525 | 1289 | |

| AKI detection rate | 1.55% | 1.61% | 1.49% | 0.045 |

| Deaths from AKI (n) | 386 | 255 | 131 | |

| AKI mortality rate | 13.7% | 16.7% | 10.2% | <0.001 |

AKI characteristics in the elderly

The mean age of the older AKI patients was 73.3 years. More of the older patients with AKI were men than women (62.1% vs 37.9%; P<0.001). Comparison of concurrent diseases in the elderly AKI patients showed that hypertension, cardiovascular disease and MODS were more common than in younger patients (44.2% vs 31.2%, P<0.001; 16.1% vs 4.6%, P<0.001; 20.9% vs 16.9%, P<0.001, respectively). However, there was no significant difference in diabetes, cancer or CKD (table 2). Elderly AKI patients underwent far fewer renal biopsies and less dialysis (1.0% vs 7.13%, P<0.001; 9.6% vs 19.2%, P<0.001, respectively) and experienced longer ICU stays. There was no significant difference between the elderly and younger AKI patients regarding mechanical ventilation, LOS, hospital cost or daily cost.

Table 2.

General characteristics of AKI patients

| Total (n=2814) | Elderly patients (n=1525) | Younger patients (n=1289) | P value | |

| Age (years) | 60.1±17.4 | 73.3±8.16 | 44.34±11.4 | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.018 | |||

| Male | 1803 (64.1%) | 947 (62.1%) | 856 (66.4%) | |

| Female | 1011 (35.9%) | 578 (37.9%) | 433 (33.6%) | |

| ICU admission | 585 (20.8%) | 337 (22.1%) | 248 (19.2%) | 0.063 |

| ICU LOS (days) | 3.2 (0–87) | 3.8 (0–87) | 2.7 (0–49) | 0.019 |

| LOS (days) | 13.2 (6.8–24.6) | 14.0 (7.14–24.9) | 13.6 (6.7–25.6) | 0.698 |

| Total cost (¥) | 22 342 (11 134–49 811) | 22 478 (11 340–50 802) | 21 253 (11 110–44 222) | 0.906 |

| Daily cost (¥) | 1888.7 (1050.9–3677.8) | 1796.2 (1008.4–3793.8) | 1681.1 (1005.6–3073.4) | 0.300 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Hypertension | 1076 (38.2%) | 674 (44.2%) | 402 (31.2%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 318 (11.3%) | 188 (12.3%) | 130 (10.1%) | 0.061 |

| CVD | 304 (10.8%) | 245 (16.1%) | 59 (4.6%) | <0.001 |

| CKD | 254 (10.4%) | 128 (9.5%) | 126 (11.5%) | 0.093 |

| Cancer | 514 (18.3%) | 284 (18.6%) | 230 (17.8%) | 0.594 |

| MODS | 537 (19.1%) | 319 (20.9%) | 218 (16.9%) | <0.001 |

| Renal biopsy | 108 (3.8%) | 16 (1.0%) | 92 (7.13%) | <0.001 |

| Dialysis | 393 (14.0%) | 146 (9.6%) | 247 (19.2%) | <0.001 |

| MV | 97 (3.4%) | 56 (3.7%) | 41 (3.2%) | 0.477 |

| Causes | ||||

| Pre-renal | 1399 (49.7%) | 816 (53.5%) | 583 (45.2%) | <0.001 |

| Renal | 960 (34.1%) | 465 (30.5%) | 495 (38.4%) | |

| Post-renal | 327 (11.6%) | 195 (12.8%) | 132 (10.2%) | |

| Unclassified | 128 (4.55%) | 49 (3.2%) | 79 (6.1%) | |

| AKI classification | ||||

| HA-AKI | 1524 (54.2%) | 920 (60.3%) | 604 (46.9%) | 0.007 |

| CA-AKI | 1290 (45.8%) | 605 (39.7%) | 685 (53.1%) | |

| AKI stage | ||||

| 1 | 825 (29.3%) | 501 (32.9%) | 324 (25.1%) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 820 (29.1%) | 460 (30.2%) | 360 (27.9%) | |

| 3 | 1169 (41.5%) | 564 (37.0%) | 605 (46.9%) |

AKI, acute kidney injury; CA-AKI, community-acquired AKI; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HA-AKI, hospital-acquired AKI; LOS, length of stay; MODS, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome; MV, mechanical ventilation.

In the elderly, pre-renal AKI accounted for 53.5% of cases and renal AKI for 30.5% of cases, while HA-AKI accounted for 60.3%. There were more pre-renal AKI and HA-AKI cases in the elderly than in younger AKI patients (table 2).

Table 3 compares HA-AKI and CA-AKI in the elderly. The mortality rate in HA-AKI patients (20.8%) was higher than that in CA-AKI patients (16.6%) (P=0.047). The average LOS was longer (18.1 days) for HA-AKI than for CA-AKI patients (12.1 days, P<0.001). A total of 169 AKI patients (12.5%) underwent dialysis during hospitalisation, with fewer HA-AKI patients receiving dialysis (10.4%) than CA-AKI patients (14.8%) (P=0.016). However, mechanical ventilation was performed for more HA-AKI (22.5%) than CA-AKI patients (9.0%) (P<0.001). There was no significant difference in the occurrence of MODS in the elderly with HA-AKI or CA-AKI.

Table 3.

Comparison of HA-AKI with CA-AKI in the elderly

| Outcome | Total (n=1354) | HA-AKI (n=710) | CA-AKI (n=644) | P value |

| LOS (days) | 13.9 (7.1–24.9) | 18.1 (10.3–31.2) | 12.1 (6.9–19.6) | <0.001 |

| MODS, n | 281 (20.8%) | 135 (19.0%) | 146 (22.7%) | 0.098 |

| Dialysis, n | 169 (12.5%) | 74 (10.4%) | 95 (14.8) | 0.016 |

| MV, n | 218 (16.1%) | 160 (22.5%) | 58 (9.0%) | <0.001 |

| In-hospital deaths, n | 255 (18.8%) | 148 (20.8%) | 107 (16.6%) | 0.047 |

Data are the median (IQR, 25th–75th percentiles) and number (percent of group) of patients in each group.

AKI, acute kidney injury; CA-AKI, community-acquired AKI; HA-AKI, hospital-acquired AKI; LOS, length of stay; MODS, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome; MV, mechanical ventilation.

Finally, we analysed the characteristics of 1354 older AKI patients by comparing those who died with those who survived (table 4). There was no significant difference between the two groups regarding gender, hypertension, diabetes, ICU LOS or dialysis treatment, but significant differences were found in age, CVD, CKD, cancer and MODS, ICU admission and mechanical ventilation. As the number of failed organs increased, the mortality rate also increased, with a mortality rate of 100% after five organs had failed. A total of 230 (17%) of the 1354 patients died, with AKI combined with another failed major organ being the most common cause of death (29.6%; 68/230); 41.6% of the elderly AKI patients who died had stage 1 disease, while 36.1% had stage 3.

Table 4.

Comparison of elderly patients with AKI who died and who survived

| Elderly AKI (n=1354) | Patients who died (n=255) | Patients who survived (n=1099) | P value | |

| Age | 73.46±8.17 | 75.65±8.41 | 72.84±8.04 | <0.001 |

| Gender | 0.816 | |||

| Male | 841 (62.1%) | 160 (62.7%) | 681 (62%) | |

| Female | 513 (37.9%) | 95 (37.3%) | 418 (38%) | |

| Hypertension | 618 (45.6%) | 121 (47.5%) | 497 (45.2%) | 0.290 |

| CVD | 227 (16.8%) | 61 (23.9%) | 166 (15.1%) | 0.001 |

| DM | 169 (12.5%) | 29 (11.4%) | 140 (12.7%) | 0.611 |

| CKD | 128 (9.5%) | 15 (5.9%) | 113 (10.3%) | 0.031 |

| Cancer | 218 (16.1%) | 69 (27.1%) | 149 (13.6%) | <0.001 |

| MODS | 281 (20.8%) | 99 (38.8%) | 182 (16.6%) | <0.001 |

| Number of failed organs | <0.001 | |||

| 2 | 230 (17.0%) | 68 (29.6%) | 162 (70.4%) | |

| 3 | 38 (2.8%) | 20 (52.6%) | 18 (47.4%) | |

| 4 | 8 (0.6%) | 6 (75.0%) | 2 (25.0%) | |

| 5 | 5 (0.4%) | 5 (100%) | 0 | |

| ICU admission | 337 (24.9%) | 73 (28.6%) | 264 (20.8%) | 0.006 |

| ICU LOS | 2.89 (0–87) | 3.16 (0–67) | 2.75 (0–87) | 0.095 |

| Dialysis | 138 (10.2%) | 18 (7.1%) | 120 (10.9%) | 0.066 |

| MV | 43 (3.2%) | 21 (8.2%) | 22 (2.0%) | 0.001 |

| AKI stage | 0.001 | |||

| 1 | 434 (32.1%) | 106 (24.4%) | 328 (75.6%) | |

| 2 | 416 (30.7%) | 57 (13.7%) | 359 (86.3%) | |

| 3 | 504 (37.2%) | 92 (18.3%) | 412 (81.7%) | |

| AKI classification | 0.047 | |||

| CA-AKI | 644 (47.6%) | 107 (16.6%) | 537 (83.4%) | |

| HA-AKI | 710 (52.4%) | 148 (20.8%) | 562 (79.2%) | |

AKI, acute kidney injury; CA-AKI, community–acquired AKI; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes; HA-AKI, hospital-acquired AKI; LOS, length of stay; MODS, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome; MV, mechanical ventilation.

Risk factors for death from AKI in the elderly

First, we screened out eight factors that might be associated with death from AKI in the elderly using univariable logistic regression analysis (table 5), and then identified the independent mortality risk factors using multivariable logistic regression analysis. Age (OR 1.041; 95% CI 1.023 to 1.059), CVD (OR 1.98; 95% CI 1.402 to 2.797), cancer (OR 2.302; 95% CI 1.654 to 3.203), MODS (OR 3.023; 95% CI 1.627 to 5.620) and mechanical ventilation (OR 2.408; 95% CI 1.187 to 4.887) were independent risk factors for mortality from AKI in the elderly. HA-AKI or CA-AKI, admission to the ICU ward, and pre-existing CKD were not independent risk factors for mortality.

Table 5.

Risk factors for death from AKI in the elderly

| Variable | β value | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Age | 0.040 | 1.041 (1.023 to 1.059) | <0.001 |

| HA-AKI or CA-AKI | 0.230 | 1.258 (0.934 to 1.695) | 0.131 |

| CKD | −0.388 | 0.678 (0.377 to 1.219) | 0.194 |

| Cancer | 0.834 | 2.302 (1.654 to 3.203) | <0.001 |

| CVD | 0.683 | 1.98 (1.402 to 2.797) | <0.001 |

| ICU admission | 0.228 | 1.256 (0.901 to 1.751) | 0.179 |

| MODS | 1.106 | 3.023 (1.627 to 5.620) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 0.879 | 2.408 (1.187 to 4.887) | 0.015 |

AKI, acute kidney injury; CA-AKI, community-acquired AKI; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HA-AKI, hospital-acquired AKI; MODS, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome.

Discussion

AKI in the elderly population is a common and devastating problem in clinical practice. Despite ’elderly' being a frequently used term in the medical literature, various ages, ranging from ≥60 years to ≥80 years are used when referring to these patients.11 12 In this study, we defined patients ≥60 years of age as being elderly.

Age was confirmed as an independent predictor of death from AKI in the elderly. Ageing is associated with concurrent disease in other organ systems, which may influence AKI outcome. Comorbidity such as diabetes and hypertension may increase AKI morbidity but was not an independent risk factor for mortality.13 14 Ali et al showed a significant increase in mortality risk with age and comorbidities.15 We also found that cardiovascular disease and cancer were independent risk factors for death. Recently, a growing number of research studies have suggested that AKI and CKD are not distinct entities but rather are closely interconnected — they influence each other and are risk factors for cardiovascular events, end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and even death.16 17 However, we found no association between CKD and AKI mortality in this study. Meier et al showed that non-critical AKI patients with pre-existing CKD had an 18% higher odds of death than non-CKD patients.18 Recently, Han et al found an gradedindependent association between a baseline eGFR below 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and HA-AKI in-hospital mortality.19 The discrepancy observed in our study may be attributed to the inclusion of CA-AKI and critical AKI patients. Furthermore, various confounders may make it difficult to identify CKD as an independent risk factor, which may even become a protective factor.20 This requires further verification.

The study showed that pre-renal AKI was the major cause of AKI in the elderly. Nash et al conducted a large prospective study and found that the most common cause of AKI in hospitalised elderly patients was decreased renal perfusion caused by volume depletion, hypotension and/or congestive heart failure.21 Susceptibility to pre-renal AKI in the elderly may be associated with typical age-associated structural and functional changes.22 As dehydration is a major health risk for the elderly, involving decreased feelings of thirst and reduced function,23 24 it is crucial to highlight the importance of rehydration as the first therapeutic approach, with timely recognition and management being important.

We also demonstrated differences between CA-AKI and HA-AKI in the elderly. Consistent with previous reports,1 patients with CA-AKI had shorter LOS than HA-AKI patients. The mortality rate was higher in patients with HA-AKI than in patients with CA-AKI, but HA-AKI patients required much less dialysis than CA-AKI patients, which may be due to the causes of AKI and the indications for dialysis.

Previous studies showed that MODS was associated with a higher mortality rate in critical AKI patients, ranging from 37% in the PICARD study25 to 60.3% in the BEST kidney study.26 Kohli et al suggested that the failure of two or more organs was an independent predictor of AKI mortality in elderly patients.27 The number of failed organs, the degree of individual organ dysfunction, and the extent of dysfunction of each organ system contribute to increasing mortality.28–30 Accordingly, we collected data on the occurrence of MODS during AKI and the number of failed organs, and found that results were consistent with previous findings: the mortality rate in the elderly with AKI increased as the number of failed organs increased. Therefore, to improve the poor prognosis of AKI in the elderly, especially with critical AKI, treatment of AKI and preventive measures focusing on other important organs should be performed in a timely manner.

This study has some limitations. First, it was a retrospective cohort study with a cross-sectional survey design, where elderly patients with AKI were compared with younger patients. However, It would have been better to compare the elderly patients with AKI with a group of elderly patients without AKI, and to confirm the results in a larger prospective cohort. Second, as the study data were collected from 15 tertiary hospitals, the clinical features and risk factors for AKI found in the study may differ from those in patients in lower-level hospitals.

In conclusion, the most common types of AKI in the elderly in China were pre-renal AKI and HA-AKI. An increasing number of failed organs increased the mortality rate of AKI in the elderly. Age, cardiovascular disease, cancer, MODS and mechanical ventilation were independent risk factors for death due to AKI in the elderly.

Main messages.

This study analysed representative, multicentre data.

The characteristics of acute kidney injury (AKI) in the elderly were examined.

Age, cardiovascular disease, cancer, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and mechanical ventilation were independent risk factors for death due to AKI in the elderly.

Current research questions.

The clinical characteristics of elderly patients without acute kidney injury (AKI) should be compared with those of elderly AKI patients of the same age and with the same length of hospital stay.

Frailty and nutritional status may affect AKI mortality in the elderly, which should therefore be adjusted for in estimating risk factors.

Epidemiological studies of AKI in the elderly in China are still rare despite the ageing population.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the staff of the department of quality management and the medical management institute from 15 hospitals for providing the data. Especially, we thank Engineer Jian-Chao Liu (Institute of Management, Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China) for his helpful sorting of the data.

Footnotes

Contributors: G-YC, ZF, X-MC and J-QL planned the study. J-QL, SL, W-LW, S-YW, F-LZ, S-SN conducted the survey and collected the data. J-QL wrote the manuscript. G-YC submitted the study.

Funding: This work was supported by the 973 Program (2013CB530800), the Twelfth Five-Year National Key Technology Research and Development Program (2015BAI12B06, 2013BAI09B05), the 863 Program (2012AA02A512) and the NSFC (81401160, 81070267).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Medical Ethics Committee of Chinese PLA General Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Xu X, Nie S, Liu Z, et al. . Epidemiology and clinical correlates of AKI in Chinese hospitalized adults. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;10:1510–8. 10.2215/CJN.02140215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang X, Bonventre JV, Parrish AR. The aging kidney: increased susceptibility to nephrotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci 2014;15:15358–76. 10.3390/ijms150915358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. KDIGO AKI Work group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl 2012;2:1–138. 10.1038/kisup.2012.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zeng X, McMahon GM, Brunelli SM, et al. . Incidence, outcomes, and comparisons across definitions of AKI in hospitalized individuals. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2014;9:12–20. 10.2215/CJN.02730313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thomas M, Sitch A, Dowswell G. The initial development and assessment of an automatic alert warning of acute kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011;26:2161–8. 10.1093/ndt/gfq710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yang L, Xing G, Wang L, et al. . Acute kidney injury in China: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet 2015;386:1465–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00344-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yilmaz R, Erdem Y. Acute kidney injury in the elderly population. Int Urol Nephrol 2010;42:259–71. 10.1007/s11255-009-9629-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Anon. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med 1992;20:864–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fry DE, Pearlstein L, Fulton RL, et al. . Multiple system organ failure. The role of uncontrolled infection. Arch Surg 1980;115:136–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gong Y, Zhang F, Ding F, et al. . Elderly patients with acute kidney injury (AKI): clinical features and risk factors for mortality. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2012;54:e47–51. 10.1016/j.archger.2011.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chronopoulos A, Cruz DN, Ronco C. Hospital-acquired acute kidney injury in the elderly. Nat Rev Nephrol 2010;6:141–9. 10.1038/nrneph.2009.234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chronopoulos A, Rosner MH, Cruz DN, et al. . Acute kidney injury in elderly intensive care patients: a review. Intensive Care Med 2010;36:1454–64. 10.1007/s00134-010-1957-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gentric A, Cledes J. Immediate and long-term prognosis in acute renal failure in the elderly. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1991;6:86–90. 10.1093/ndt/6.2.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Klouche K, Cristol JP, Kaaki M, et al. . Prognosis of acute renal failure in the elderly. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1995;10:2240–3. 10.1093/ndt/10.12.2240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ali T, Khan I, Simpson W, et al. . Incidence and outcomes in acute kidney injury: a comprehensive population-based study. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;18:1292–8. 10.1681/ASN.2006070756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chawla LS, Kimmel PL. Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease: an integrated clinical syndrome. Kidney Int 2012;82:516–24. 10.1038/ki.2012.208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chawla LS, Eggers PW, Star RA, et al. . Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease as interconnected syndromes. N Engl J Med 2014;371:58–66. 10.1056/NEJMra1214243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meier P, Bonfils RM, Vogt B, et al. . Referral patterns and outcomes in noncritically ill patients with hospital-acquired acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;6:2215–25. 10.2215/CJN.01880211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Han YC, Tu Y, Liu H, et al. . Hospital-acquired acute kidney injury: an analysis of baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate and in-hospital mortality. J Nephrol 2016;29:411–8. 10.1007/s40620-015-0238-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Singh P, Rifkin DE, Blantz RC. Chronic kidney disease: an inherent risk factor for acute kidney injury? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;5:1690–5. 10.2215/CJN.00830110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nash K, Hafeez A, Hou S. Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis 2002;39:930–6. 10.1053/ajkd.2002.32766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Denic A, Glassock RJ, Rule AD. Structural and functional changes with the aging kidney. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2016;23:19–28. 10.1053/j.ackd.2015.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thunhorst RL, Beltz T, Johnson AK. Age-related declines in thirst and salt appetite responses in male Fischer 344×Brown Norway rats. Physiol Behav 2014;135:180–8. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cowen LE, Hodak SP, Verbalis JG. Age-associated abnormalities of water homeostasis. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2013;42:349–70. 10.1016/j.ecl.2013.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mehta RL, Pascual MT, Soroko S, et al. . Spectrum of acute renal failure in the intensive care unit: the PICARD experience. Kidney Int 2004;66:1613–21. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00927.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, et al. . Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA 2005;294:813–8. 10.1001/jama.294.7.813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kohli HS, Bhat A, Aravindan AN, et al. . Predictors of mortality in elderly patients with acute renal failure in a developing country. Int Urol Nephrol 2007;39:339–44. 10.1007/s11255-006-9137-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ferreira FL, Bota DP, Bross A, et al. . Serial evaluation of the SOFA score to predict outcome in critically ill patients. JAMA 2001;286:1754–8. 10.1001/jama.286.14.1754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mayr VD, Dünser MW, Greil V, et al. . Causes of death and determinants of outcome in critically ill patients. Crit Care 2006;10:R154 10.1186/cc5086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Doi K, Rabb H. Impact of acute kidney injury on distant organ function: recent findings and potential therapeutic targets. Kidney Int 2016;89:555–64. 10.1016/j.kint.2015.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

postgradmedj-2017-135455supp001.docx (15.3KB, docx)