Abstract

Objective

We evaluated current evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) regarding the effectiveness of chemical peeling for treating acne vulgaris.

Methods

Standard Cochrane methodological procedures were used. We searched MEDLINE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and EMBASE via OvidSP through April 2017. Reviewers independently assessed eligibility, risk of bias and extracted data.

Results

Twelve RCTs (387 participants) were included. Effectiveness was not significantly different: trichloroacetic acid versus salicylic acid (SA) (percentage of total improvement: risk ratio (RR) 0.89; 95% CI 0.73 to 1.10), glycolic acid (GA) versus amino fruit acid (the reduction of inflammatory lesions: mean difference (MD), 0.20; 95% CI −3.03 to 3.43), SA versus pyruvic acid (excellent or good improvement: RR 1.11; 95% CI 0.73 to 1.69), GA versus SA (good or fair improvement: RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.18), GA versus Jessner’s solution (JS) (self-reported improvements: RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.44 to 2.26), and lipohydroxy acid versus SA (reduction of non-inflammatory lesions: 55.6%vs48.5%, p=0.878). Combined SA and mandelic acid peeling was superior to GA peeling (percentage of improvement in total acne score: 85.3%vs68.5%, p<0.001). GA peeling was superior to placebo (excellent or good improvement: RR 2.30; 95% CI 1.40 to 3.77). SA peeling may be superior to JS peeling for comedones (reduction of comedones: 53.4%vs26.3%, p=0.001) but less effective than phototherapy for pustules (number of pustules: MD −7.00; 95% CI −10.84 to −3.16).

Limitations

The methodological quality of the included RCTs was very low to moderate. Meta-analysis was not possible due to the significant clinical heterogeneity across studies.

Conclusion

Commonly used chemical peels appear to be similarly effective for mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris and well tolerated. However, based on current limited evidence, a robust conclusion cannot be drawn regarding any definitive superiority or equality among the currently used chemical peels. Well-designed RCTs are needed to identify optimal regimens.

Keywords: chemical peeling, acne vulgaris, systematic review, treatment, comedone, papule

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses protocols and Cochrane methodological procedures.

Twelve randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with 387 participants were included.

The methodological quality of the included RCTs was very low to moderate.

A meta-analysis cannot be performed due to the significant heterogeneity across the RCTs.

Introduction

Acne is one of the most common skin disorders and is prevalent in most ethnic populations.1 Acne affects 85%–90% of adolescents and may persist into adulthood.2 3 Acne vulgaris can negatively affect an individual’s appearance and self-esteem, thereby causing anxiety, depression, poor quality of life and even suicidal thought.1 2 Skin lesions of acne vulgaris are classified as either non-inflammatory (comedones) or inflammatory (papules, pustules, nodules and cysts). Acne vulgaris treatments include systemic therapies (oral antibiotics and retinoid), topical therapies (benzoyl peroxide) and physical modalities (laser therapy and chemical peeling).

Chemical peeling is a skin resurfacing procedure commonly used for facial rejuvenation and aesthetics.3 It causes a manageable injury to the skin, thus resulting in subsequent regeneration of a new epidermal layer of the dermal tissues.4 The injury depth is determined by the concentration of acid used, and by the type of vehicle, buffering and duration of skin contact. Therefore, chemical peels are classified as superficial (destroying the epidermis), moderate (destroying the papillary dermis and upper reticular dermis) or deep (destroying part or all of the mid-reticular dermis).5 Although often used to treat acne, chemical peeling is also widely used as a cosmetic treatment for melasma, photoaging and lentigines.5 Superficial peels are generally used for acne vulgaris, whereas deep peels are used to treat acne scars. Commonly used agents for chemical peels are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

The abbreviations of commonly used chemical peels for acne vulgaris4–6 26–28

| Chemical peels | Abbreviations |

| α-Hydroxy acid | AHA |

| Amino fruit acid | AFA |

| Glycolic acid | GA |

| Mandelic acid | MA |

| Tartaric acid | TA |

| β-Hydroxy acid | BHA |

| Salicylic acid | SA |

| Azelaic acid | AZA |

| Lipohydroxy acid | LHA |

| Jessner’s solution* | JS |

| Pyruvic acid | PA |

| Retinoic acid | RA |

| Trichloroacetic acid | TCA |

*Jessner’s solution is a premixed formula containing 14% salicylic acid, 14% lactic acid and 14% resorcinol.

The exact pathogenesis of acne vulgaris remains unclear. However, the proliferation of Propionibacterium acnes, increased levels of inflammatory cytokines and sebum production, and follicular hyperkeratinisation are involved.3 Chemical peels have antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, keratolytic and comedolytic effects, and they can reduce sebum production. Therefore, chemical peels have been widely used to treat acne vulgaris, either as a supplementary therapy or as a maintenance therapy.3 5 6

Despite their wide application, evidence regarding the effectiveness of chemical peels in the treatment of acne vulgaris is limited. A 2016 recommendation for the treatment of acne vulgaris indicated that chemical peels were supported by level B evidence, namely, ‘inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence’.7 This recommendation was based on the evaluation of two trials8 9 and a previously published guideline,6 and it only included research from the PubMed and the Cochrane Library databases, from May 2006 to September 2014. Therefore, potential evidence from other important medical databases was possibly omitted. In addition, new randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were performed after September 2014.9–16 Thus, we performed a systematic review to summarise current evidence regarding the effectiveness of chemical peeling for acne vulgaris and to evaluate the validity of the aforementioned recommendations.

Methods

Systematic search of the literature

This review was performed according to the guidelines for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)17 protocols and the Standard Cochrane methodological procedures.18 The following databases were searched until 25 April 2017, using the strategy summarised in online supplementary table 1: MEDLINE via OvidSP (from 1946), EMBASE via OvidSP (from 1974) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2017, issue 4.

bmjopen-2017-019607supp001.pdf (40.3KB, pdf)

We also hand-searched all bibliographies of the included and excluded studies and previous systematic reviews to identify further relevant trials.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included all RCTs addressing any chemical peel (compared with placebo or any other treatment) for the treatment of acne vulgaris in any study population. Studies that recruited patients with sequelae of acne such as postinflammatory dyschromia or scarring, evaluated the combined effects of chemical agents and other therapies such as laser therapy, were quasi-RCTs and were not published in English were excluded.

Selection of studies

Two authors (XC and MY) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts identified from the searches and selected possible relevant studies. After reviewing the full text of these studies, the two authors independently decided on which studies to include and exclude and documented the reasons for exclusion. Any discrepancy in the selection was resolved through discussion.

Data extraction

Two authors (XC and MY) independently extracted the information from the included studies using the ‘characteristics of included studies form’ recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions.18 Another author (WS) verified and compared the data-extraction forms.

Assessment of the risk of bias in included trials

Two authors (XC and MY) independently evaluated the risk of bias in the included trials using the methods recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions.18 Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. The Cochrane risk of bias for each included trial was classified as low, high or unclear.

Measure of treatment effects

Dichotomous outcomes (such as the percentage of meaningful improvement in the total number of lesions) were reported, when possible, as risk ratios (RRs), with the associated 95% CIs. Continuous outcomes (such as the number of inflammatory lesions) were reported as the mean difference (MD), with the associated 95% CI.

Heterogeneity and data synthesis

Significant clinical heterogeneity across the included RCTs was identified. Specifically, the skin type of participants, interventions (eg, the type, concentration and regimen of chemical peeling agents) and outcome measurements were all significantly different across the included RCTs. Therefore, it was not possible to merge data from different trials to perform a meta-analysis.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved.

Results

Description of studies

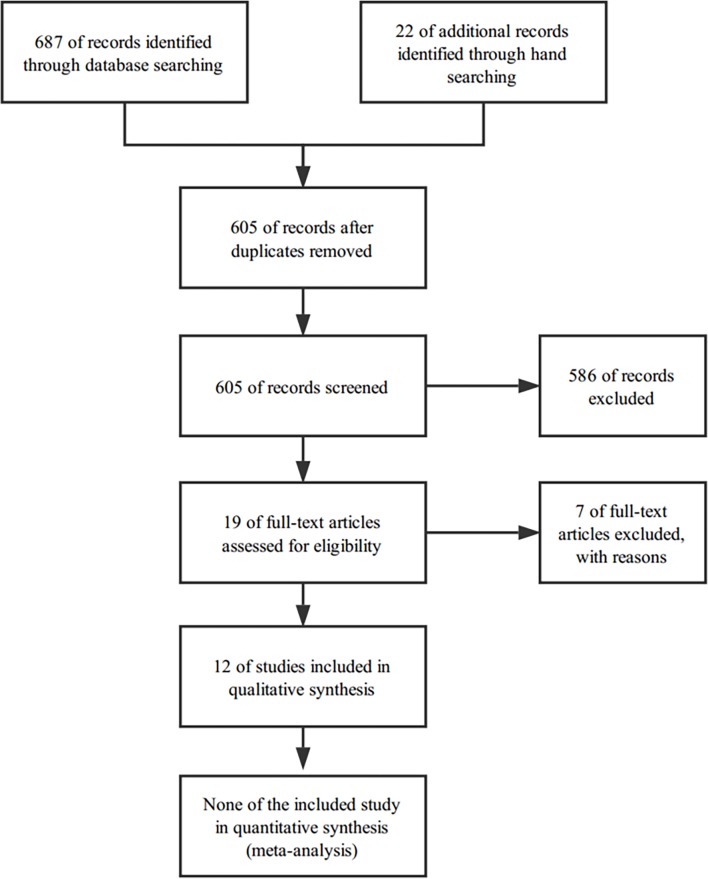

After removing duplicates, we identified 605 articles during the initial search. Of these, 586 were discarded after screening the titles and abstracts, leaving 19 studies for full review. Another 7 of the 19 studies were excluded after this review. The reasons for exclusion are summarised in online supplementary table 2. Our final analysis included 12 RCTs, providing data from 387 participants. The PRISMA diagram for study selection is presented in figure 1. Relevant characteristics of the included RCTs are summarised in table 2.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram of the study flow.

Table 2.

Summary of relevant characteristics of included studies

| Studies | Publication year | Study design | Country | Sample size | Women (%) |

Fitzpatrick skin type | Acne severity | Interventions | Main outcomes | Follow-up (weeks) |

| Abdel et al10 | 2015 | Single-centre, double-blind, split-face RCT. | Egypt | 20 | 85 | III, IV, V | Mild to moderate | 25% TCA versus 30% SA (in hydroethanolic vehicle) |

|

10 |

| Alba et al11 | 2017 | Single-centre, single-blind RCT. | Brazil | 22 | 41 | II, III, IV, VI | Mild to moderate | 10% SA (in cream gel) versus phototherapy |

|

10 |

| Bae et al12 | 2013 | Single-centre, single-blind, split-face RCT. | Korea | 13 | 0 | III or IV | Mild to moderate | 30% SA versus JS |

|

8 |

| Dayal et al13 | 2017 | Single-centre, single-blind RCT. | India | 40 | 35 | N/A | Mild to moderate | 30% SA versus JS. |

|

12 |

| EI Refaei et al14 | 2015 | Single-centre, open-label RCT. | Egypt | 40 | 80 | I, II, III, IV | Mild to very severe | 20% SA+10% MA (in ethyl alcohol vehicle) versus 35% GA (in distilled water) |

|

20 |

| Ilknur et al8 | 2010 | Single-centre, single-blind, split-face RCT. | Turkey | 30 | N/A | II, III | Mild to moderate | GA (from 20% to 70%) versus AFA (from 20% to 60%) |

|

24 |

| Jaffary et al15 | 2016 | Multi-centre, single-blind RCT. | Iran | 86 | 92 | N/A | Mild to moderate | 30% SA (in alcohol vehicle) versus 50% PA (in hydro alcoholic vehicle) |

|

8 |

| Kaminaka et al16 | 2014 | Single-centre, double-blind, split-face RCT. | Japan | 25 | 64 | N/A | Moderate to severe | 40% GA versus placebo (hydrochloric acid in polyethylene glycol vehicle) |

|

10 |

| Kessler et al19 | 2008 | Single-centre, double-blind, split-face RCT. | USA | 20 | 65 | N/A | Mild to moderate | 30% GA versus 30% SA |

|

20 |

| Kim et al20 | 1999 | Single-centre, single-blind, split-face RCT. | Korea | 26 | 84.6 | III, IV | Mild to moderate | 70% GA versus JS (resorcinol, salicylic acid, lactic acid in ethanol) |

|

8 |

| Leheta21 | 2009 | Single-centre, single-blind, RCT. | Egypt | 45 | N/A | II, III, IV | Mild to moderate | 20% TCA versus PDL |

|

48 |

| Levesque et al9 | 2011 | Single-centre, open-label, split-face RCT. | USA | 20 | 95 | N/A | N/A | LHA (5% or 10%) versus SA (20% or 30%) |

|

14 |

AFA, amino fruit acid; GA, glycolic acid; JS, Jessner’s solution; LHA, lipohydroxy acid; MA, mandelic acid; MAS, Michaelson Acne Score; N/A, not available; PA, pyruvic acid; PDL, pulsed dye laser; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SA, salicylic acid: TCA, trichloroacetic acid.

bmjopen-2017-019607supp002.pdf (79.6KB, pdf)

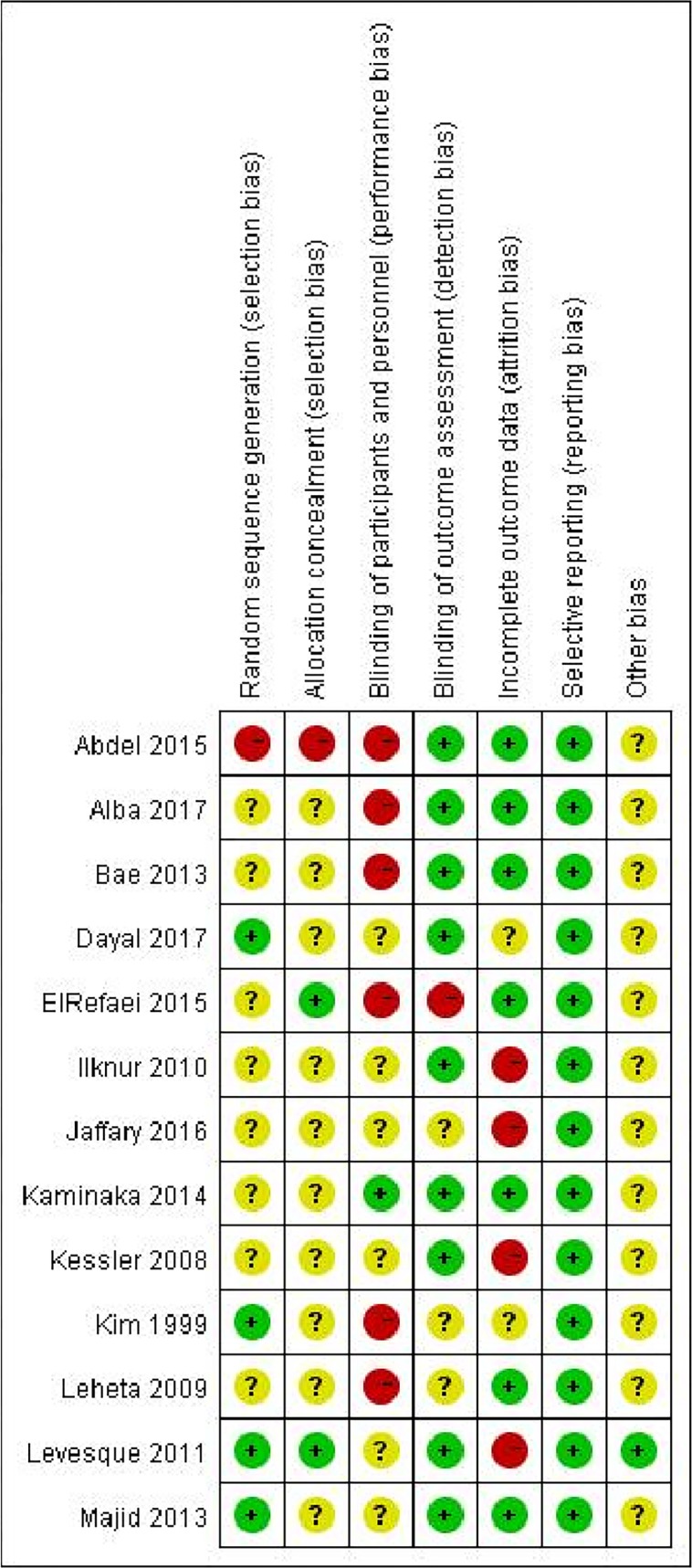

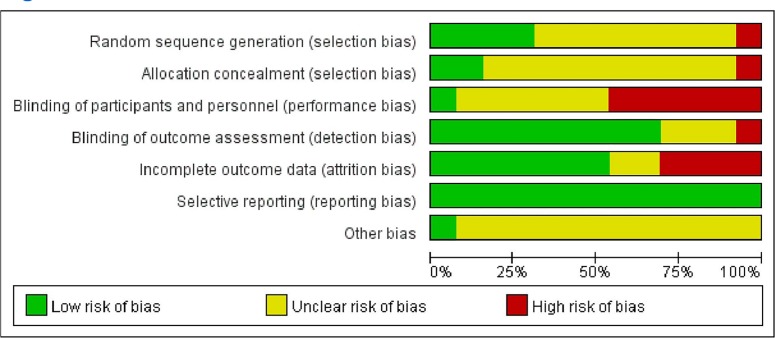

Risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of included RCTs was generally low to moderate; however, in some cases, it was very low. The risk of bias in each included study is shown in figure 2, with the percentage of each risk of bias item across studies summarised in figure 3.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary for each study.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary graph for all included studies.

Effects of interventions

Due to significant differences across studies with regard to interventions (different chemical peels and regimens), outcomes and follow-up durations, data from the different studies could not be combined to perform a meta-analysis. We identified a total of eight different chemical peels and grouped the data into 11 comparisons.

Comparison 1: trichloroacetic acid peel versus salicylic acid peel

One RCT (20 participants, split-face comparison) compared 25% trichloroacetic acid (TCA; every 2 weeks, four sessions) to 30% salicylic acid (SA; every 2 weeks, four sessions) for the treatment of mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris. Skin lesions significantly improved, from baseline, in both treatment groups, with no significant difference between TCA and SA in terms of the percentage of total improvement for all lesions (85% vs 95%; RR 0.89; 95% CI 0.73 to 1.10), for non-inflammatory lesions (80% vs 70%; RR 1.14; 95% CI 0.80 to 1.64) and for inflammatory lesions (80% vs 85%; RR 0.94; 95% CI 0.71 to 1.25).10

Adverse events

No adverse event was identified for the SA peel. For the TCA peel, four patients (20%) reported hyperpigmentation that lasted for 3–4 weeks.10

Comparison 2: SA peel versus phototherapy

One RCT (22 participants) compared 10% SA (once every week, 10 sessions) to phototherapy (once every week, 10 sessions). Both interventions significantly improved acne lesions, with no significant difference between the two interventions in terms of the reduction in the number of comedones (MD 2.00; 95% CI −3.67 to 7.67) and papules (MD −1.00; 95% CI −4.40 to 2.40). However, the SA peel did not reduce the number of pustules to the same extent as phototherapy (MD −7.00; 95% CI −10.84 to −3.16).11

Adverse events

No information regarding adverse effects was reported.11

Comparison 3: SA peel versus Jessner’s solution peel

Two RCTs compared SA with Jessner’s solution (JS) peels.12 13 Because of significant differences in the treatment regimen, measured outcomes and follow-up duration, data from these two studies could not be combined for analysis.

One RCT (13 patients, split-face comparison) compared 30% SA (every 2 weeks, three sessions) to JS (every 2 weeks, three sessions).12 The authors stated that SA ‘seemed to be more effective than’ JS for the treatment of non-inflammatory lesions. However, relevant data supporting this conclusion were not clearly described. Furthermore, the authors reported that both SA and JS were effective in reducing inflammatory lesions; however, they did not compare the effects of SA and JS on this outcome.

Another RCT (40 patients) also compared 30% SA (every 2 weeks, six sessions) with JS (every 2 weeks, six sessions).13 SA was superior to JS in terms of overall percentage decrease in the mean number of comedones (53.4% and 26.3%, respectively, p=0.001), with equivalent outcomes for papules (71.0% and 61.5%, respectively, p=0.870) and pustules (70.3% and 76.7%, respectively, p=0.570). The proportional decreases in the mean Michaelson Acne Score, before and after treatment, were greater for SA than for JS (60.4% and 34.1%, respectively, p=0.002).

Adverse events

Initial burning sensations, postpeeling erythema and mild scaling were common symptoms that were comparable for the SA and JS groups.13 One patient reported intense scaling on the side that was treated with SA.12 There was no report of hyperpigmentation.

Dayal et al reported that SA and JS were both well tolerated, although SA induced more burning and stinging sensation (65% and 45%, respectively; RR 2.27; 95% CI 0.64 to 8.11; non-significant between-group difference).13 However, postpeeling erythema was less common in the SA group than in the JS group (20% and 30%, respectively; RR 0.58; 95% CI 0.14 to 2.50; non-significant between-group difference). Hyperpigmentation was rare in both groups (5% and 15%, respectively; RR 0.30; 95% CI 0.30 to 3.15).

Comparison 4: SA plus mandelic acid peel versus glycolic acid peel

One RCT (40 patients) compared 20% SA plus 10% mandelic acid (MA; every 2 weeks, six sessions) with 35% glycolic acid (GA; every 2 weeks, six sessions).14 The combination of SA and MA was superior to GA in terms of the percentage of improvement, from baseline, in comedones (90.2% and 35.9%, respectively, p<0.05), papules (81.7% and 77.8%, respectively, p=0.006) and pustules (85.4% and 75.7%, respectively, p<0.001), as well as in the total acne score (85.3% and 68.5%, respectively, p<0.001).

Adverse events

There was no significant difference between these two intervention groups in terms of burning or stinging sensations (20% and 10%, respectively; RR 2.00; 95% CI 0.41 to 9.71), skin dryness (15% and 10%, respectively; RR 1.50; 95% CI 0.28 to 8.04) and acne flare-up (10% each; RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.16 to 6.42). However, the combination of SA and MA induced more visible desquamation than GA (80% and 40%, respectively; RR 2.00; 95% CI 1.12 to 3.57).

Comparison 5: GA peel versus amino fruit acid peel

One RCT (30 patients, split-face comparison) compared GA (at concentrations of 20%, 35%, 50% and 70%; every 2 weeks, 12 sessions) with amino fruit acid (AFA; at similar concentrations of 20%, 30%, 40%, 50% and 60%; every 2 weeks, 12 sessions).8 Both peeling agents significantly improved acne lesions and had comparable effectiveness in reducing the number of non-inflammatory lesion counts (MD 2.35; 95% CI −18.66 to 23.36), the reduction of inflammatory lesions (MD 0.20; 95% CI −3.03 to 3.43) and patient’s choice of future treatment (GA 45.8%; AFA 54.2%; RR 0.85; 95% CI 0.48 to 1.50).

Adverse events

All patients reported erythema at least once for both peels during the follow-up period. Oedema was more common for GA than for AFA (91.7% and 50%, respectively; RR 1.83; 95% CI 1.21 to 2.78).8 The incidence of frosting was comparable for both GA and AFA peels (29.2% vs 16.7%, respectively; RR 1.75; 95% CI 0.59 to 5.21). Of note, all patients reported discomfort that negatively affected daily life with the GA peel.

Comparison 6: SA peel versus pyruvic acid peel

One RCT (86 patients) compared 30% SA (every 2 weeks, five sessions) with 50% pyruvic acid (PA; every 2 weeks, five sessions).15 The two peels had similar effects for reducing comedones (MD 7.45; 95% CI −18.46 to 33.36), papules (MD −0.20; 95% CI −5.36 to 4.96) and pustules (MD −1.03; 95% CI −2.01 to 0.05). The achievement of an excellent or good improvement in all lesions was comparable for both SA and PA peels (66.7% and 60%, respectively; RR 1.11; 95% CI 0.73 to 1.69).15

Adverse events

Burning sensations were very common (>85%) for both peels. The incidences of scaling, erythema and itching were also reported to be comparable (with no data presented). Hyperpigmentation was rare and comparable for the SA and PA peels (11.1% and 8%, respectively; RR 1.39; 95% CI 0.25 to 7.64).

Comparison 7: GA peel versus placebo

One RCT (25 patients, split-face comparison) compared 40% GA (every 2 weeks, five sessions) with a placebo (every 2 weeks, five sessions).16 GA was significantly superior to the placebo for reducing the number of non-inflammatory lesions (no data available, p<0.01), inflammatory lesions (no data available, p<0.01) and total lesions (no data available, p<0.01).16 The achievement of excellent or good improvement in all lesions was also superior for GA than for the placebo (92% vs 40%, respectively; RR 2.30; 95% CI 1.40 to 3.77).

Adverse events

The authors reported that most patients experienced ‘transient post-treatment mild erythema that lasted a few minutes at most’ but no supporting data were presented.16 Mild dryness was less common in the GA group than in the placebo group (28% and 100%, respectively; RR 0.29; 95% CI 0.16 to 0.54); however, the incidence of scaling was comparable between the groups (16% and 12%, respectively; RR 1.33; 95% CI 0.33 to 5.38). A flare-up rate of 12% was reported for GA, whereas no flare-up was reported for the placebo, although this difference was not significant (RR 7.00; 95% CI 0.38 to 128.87).

Comparison 8: GA peel versus SA peel

One RCT (20 patients, split-face comparison) compared 30% GA (every 2 weeks, six sessions) with 30% SA (every 2 weeks, six sessions).19 Good or fair improvement in the total number of lesions at 1 month post-treatment was achieved with both GA and SA (94.1% each; RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.18). However, the mean number of all lesions was significantly higher on the GA-treated side than on the SA-treated side after a 2-month follow-up with no treatment (no data available, p<0.01). In terms of the patients’ self-assessments, 41% of patients preferred GA, whereas35% preferred SA (RR 1.17; 95% CI 0.49 to 2.75).

Adverse events

The authors reported that both GA and SA were safe and well tolerated, with no difference in adverse events rates between the two peels. The most common adverse events were scaling, peeling and erythema (no data available).

Comparison 9: GA peel versus JS peel

One RCT (26 patients, split-face comparison) compared 70% GA (every 2 weeks, three sessions) with JS (every 2 weeks, three sessions).20 Both GA and JS had similar effects and improved acne scores by ≥0.5 (50% each; RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.58 to 1.72). Self-reported improvements were equivalent for GA and JS (30.7% and 30.7%, respectively; RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.44 to 2.26), as were the choices for future treatment (50% and 30.7%, respectively; RR 1.63; 95% CI 0.81 to 3.65).

Adverse events

Erythema was common for both peels (no data available). However, JS induced scaling that negatively influenced patients’ daily life (GA 0%; JS 36%; RR 0.05; 95% CI 0 to 0.86). Two patients could not tolerate the 70% GA treatment due to the development of acute eczema, crusting and oozing.

Comparison 10: TCA peel versus non-purpuric pulsed dye laser

One RCT (45 patients) compared 25% TCA peel (every 2 weeks, six sessions) with non-purpuric pulsed dye laser (every 2 weeks, six sessions).21 The mean acne severity score was significantly improved, from baseline, for both TCA and laser therapy (MD 0.28; 95% CI −0.33 to 0.89); the clinical response was equivalent for both agents (40% and 46.2%, respectively; RR 0.87; 95% CI 0.37 to 2.04). However, the mean remission period after treatment was significantly shorter for TCA than for laser therapy (MD −1.60 months; 95% CI −1.85 to −1.35).

Adverse events

The authors classified adverse events as follows: none, trace, mild, moderate and severe. No severe adverse events were reported. Two patients (13%) in the TCA peel group and three (23.1%) in the laser therapy group reported moderate adverse events (RR 0.58; 95% CI 0.11 to 2.94). Mild adverse events were reported for six patients (40%) in the TCA peel group and five (38.5%) in the laser therapy group (RR 1.04; 95% CI 0.41 to 2.62). Both treatments were considered to be well tolerated.

Comparison 11: lipohydroxy acid peel versus SA peel

One RCT (20 patients) compared lipohydroxy acid (LHA; 5% or 10%, every 2 weeks, six sessions) with SA (20% or 30%, every 2 weeks, six sessions).9 Both LHA and SA reduced the number of non-inflammatory lesions (55.6% and 48.5%, respectively, p=0.878) and inflammatory lesions (no data available, p=0.111).

Adverse events

Both LHA and SA peels were well-tolerated. The global tolerance for the SA peel was better than that for the LHA peel on patient assessment (no data available, p=0.028) but there was no difference with repsect to investigator assessment (no data available, p=0.546).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review addressing chemical peels for treating acne vulgaris. Based on our analysis of the data presented in the 12 included RCTs, chemical peeling is an overall positive method of treating acne vulgaris. The following comparisons demonstrated the equivalence of peels for the treatment of acne vulgaris: TCA versus SA, GA versus AFA, SA versus PA, GA versus SA, GA versus JS and LHA versus SA. Moreover, the combination of SA and MA results in a more effective peeling than GA. Furthermore, SA was found to be more effective than JS for the treatment of comedones but less effective than phototherapy in treating pustules. The effectiveness of TCA is comparable with that of pulsed dye laser therapy but the laser provided a longer period of remission.

All chemical peels evaluated were well tolerated. The most common adverse events were as follows: transient burning or stinging sensations, postpeeling erythema or scaling, and topical oedema or dryness. A few patients reported acne flare-ups with the combination of SA and MA peel and with GA alone. Hyperpigmentation was a rare adverse event reported by patients treated with TCA, SA and JS peels. Of note, this RCT did not have sufficient power to identify all adverse events, especially rare adverse events, due to the limited sample size.22

The information provided in our review may assist dermatologists with selecting the most appropriate chemical peels to treat acne vulgaris. However, our findings should be considered with caution because the included RCTs were performed in different countries and recruited individuals of different ethnicities. The choice of chemical peels should be individualised, based on the patient’s skin type, history of acne or other skin diseases and relevant treatments, and expectations. For example, chemical peels, especially medium or deep peels, are unsuitable for those with a Fitzpatrick skin type V or VI because these peels may cause dyspigmentation and scarring in these patients.23 24 In fact, most included studies recruited patients with a Fitzpatrick skin type I–IV, although some studies did not report the skin type. In addition, most included studies focused on mild-to-moderate acne.

There is currently no consensus regarding the standardised regimen for chemical peeling because the optimal concentration, treatment interval and duration for different chemical peels remain unclear. In our review, the regimen of chemical peels varied significantly across studies. For example, the concentration of GA used in different RCTs varied from 10% to 70%, and the treatment durations varied from 6 to 24 weeks. Studies are warranted to compare different regimens of the same chemical peel in order to determine the optimal regimen for each peeling agent.

There is an emerging trend of using a combination of peeling agents because of the belief that better clinical results can be achieved while reducing the risk of adverse events.3 For instance, Vitalize Peel contains both SA and lactic acid, while Micropeel Plus contains SA and GA for treating acne vulgaris.5 However, we could not find any RCT to confirm the efficacy of the premixed chemical peeling agents for acne. In the future, more attention should be focused on these premixed formulations of chemical peels.

In this review, we surprisingly found that only one RCT16 compared a chemical peeling agent (GA) with placebo for acne vulgaris. However, more than 10 chemical peeling agents have actually been applied. Further well-designed RCTs are needed to compare other chemical peels with placebo. A network meta-analysis based on these RCTs should provide more valuable and robust evidence for clinical practice. Additionally, the outcome measurements were significantly different across the included RCTs which made it difficult to compare or merge the results of different studies. Therefore, we suggest that the future version of the guideline of care for the management of acne vulgaris should make recommendations regarding the standard of outcome measurements.

Our review has some limitations. First, all included studies were of very low-to-moderate methodological quality with small sample sizes which might have introduced bias. However, we evaluated for bias in each study. For example, most of the included RCTs did not describe the method of randomisation. It is important to adhere to the recommendations of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials statement to avoid incomplete and inadequate reporting and to improve the quality of the evidence.25 Second, this review did not investigate the effects of chemical peeling for acne scarring although chemical peels are used clinically for this indication.26 Finally, as previously discussed, the absence of a standardised peeling regimen limits the translation of our findings to clinical practice.

Conclusions

Implication for practice

Commonly used chemical peels appear to be similarly effective for mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris and well tolerated. However, based on current limited evidence, we could not draw a robust conclusion regarding any definitive superiority or equality among the currently used agents for chemical peeling.

Implications for research

Well-designed and well-reported RCTs are needed to provide high-quality evidence to inform practice, particularly regarding the optimal formulation and regimen for chemical peeling agents. Comparisons with placebo or each other should be performed for various ethnic populations and skin types. In addition, standard outcome measurements for the management of acne vulgaris are needed.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: XC and LL designed the protocol. XC and MY searched the literature, extracted the data and analysed the data. XC, SW, MY and LL interpreted the data and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the publication of this work.

Funding: This review was supported by a grant from the Sichuan Provincial Science and Technology Department (Grant number: 2017JY0277).

Disclaimer: The funder had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Sathish D, Shayeda A, Rao YM. Acne and its treatment options: a review. Curr Drug Deliv 2011;8:634–9. 10.2174/156720111797635540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bhate K, Williams HC. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol 2013;168:474–85. 10.1111/bjd.12149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kontochristopoulos G, Platsidaki E. Chemical peels in active acne and acne scars. Clin Dermatol 2017;35:179–82. 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Salam A, Dadzie OE, Galadari H. Chemical peeling in ethnic skin: an update. Br J Dermatol 2013;169(Suppl 3):82–90. 10.1111/bjd.12535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jackson A. Chemical peels. Facial Plast Surg 2014;30:026–34. 10.1055/s-0033-1364220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dréno B, Fischer TC, Perosino E, et al. . Expert opinion: efficacy of superficial chemical peels in active acne management--what can we learn from the literature today? Evidence-based recommendations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2011;25:695–704. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03852.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. . Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016;74:945–73. 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ilknur T, Demirtaşoğlu M, Biçak MU, et al. . Glycolic acid peels versus amino fruit acid peels for acne. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2010;12:242–5. 10.3109/14764172.2010.514919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Levesque A, Hamzavi I, Seite S, et al. . Randomized trial comparing a chemical peel containing a lipophilic hydroxy acid derivative of salicylic acid with a salicylic acid peel in subjects with comedonal acne. J Cosmet Dermatol 2011;10:174–8. 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2011.00566.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abdel Meguid AM, Elaziz Ahmed Attallah DA, Omar H. Trichloroacetic acid versus salicylic acid in the treatment of acne vulgaris in dark-skinned patients. Dermatol Surg 2015;41:1398–404. 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alba MN, Gerenutti M, Yoshida VM, et al. . Clinical comparison of salicylic acid peel and LED-Laser phototherapy for the treatment of Acne vulgaris in teenagers. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2017;19:49–53. 10.1080/14764172.2016.1247961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bae BG, Park CO, Shin H, et al. . Salicylic acid peels versus Jessner’s solution for acne vulgaris: a comparative study. Dermatol Surg 2013;39:248–53. 10.1111/dsu.12018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dayal S, Amrani A, Sahu P, et al. . Jessner’s solution vs. 30% salicylic acid peels: a comparative study of the efficacy and safety in mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Dermatol 2017;16:43–51. 10.1111/jocd.12266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. El Refaei AM, Abdel Salam HA, Sorour NE. Salicylic–mandelic acid versus glycolic acid peels in Egyptian patients with acne vulgaris. Journal of the Egyptian Womenʼs Dermatologic Society 2015;12:196–202. 10.1097/01.EWX.0000464740.18592.42 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jaffary F, Faghihi G, Saraeian S, et al. . Comparison the effectiveness of pyruvic acid 50% and salicylic acid 30% in the treatment of acne. J Res Med Sci 2016;21 10.4103/1735-1995.181991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaminaka C, Uede M, Matsunaka H, et al. . Clinical evaluation of glycolic acid chemical peeling in patients with acne vulgaris: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, split-face comparative study. Dermatol Surg 2014;40:314–22. 10.1111/dsu.12417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]: The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011. www.handbook.cochrane.org

- 19. Kessler E, Flanagan K, Chia C, et al. . Comparison of alpha- and beta-hydroxy acid chemical peels in the treatment of mild to moderately severe facial acne vulgaris. Dermatol Surg 2008;34:45–51. discussion 51 10.1097/00042728-200801000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim SW, Moon SE, Kim JA, et al. . Glycolic acid versus Jessner’s solution: which is better for facial acne patients? A randomized prospective clinical trial of split-face model therapy. Dermatol Surg 1999;25:270–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leheta TM. Role of the 585-nm pulsed dye laser in the treatment of acne in comparison with other topical therapeutic modalities. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2009;11:118–24. 10.1080/14764170902741329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wahab IA, Pratt NL, Kalisch LM, et al. . The detection of adverse events in randomized clinical trials: can we really say new medicines are safe? Curr Drug Saf 2013;8:104–13. 10.2174/15748863113089990030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Been MJ, Mangat DS. Laser and face peel procedures in non-Caucasians. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 2014;22:447–52. 10.1016/j.fsc.2014.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Handog EB, Datuin MS, Singzon IA. Chemical peels for acne and acne scars in asians: evidence based review. J Cutan Aesthet Surg 2012;5:239–46. 10.4103/0974-2077.104911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boutron I, Altman DG, Moher D, et al. . CONSORT statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: a 2017 update and a CONSORT extension for nonpharmacologic trial abstracts. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:40–7. 10.7326/M17-0046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Abdel Hay R, Shalaby K, Zaher H, et al. . Interventions for acne scars. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;4:CD011946 10.1002/14651858.CD011946.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Arif T. Salicylic acid as a peeling agent: a comprehensive review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2015;8:455–61. 10.2147/CCID.S84765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sharad J. Glycolic acid peel therapy - a current review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2013;6:281–8. 10.2147/CCID.S34029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-019607supp001.pdf (40.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-019607supp002.pdf (79.6KB, pdf)