Abstract

Objectives

To undertake an economic analysis assessing the cost-effectiveness of a single dose of oral dexamethasone compared with placebo for the relief of sore throat.

Design

A UK-based, multicentre, two arm, individually randomised, double blind trial.

Setting and population

Adults (≥18 years) with acute sore throat and painful swallowing judged to be infective in origin, recruited and randomised in primary care. Intervention: a single dose of 10 mg oral dexamethasone compared with placebo given at primary care visit.

Main outcome

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), cost per quality-adjusted symptom resolution using the EuroQol-five dimensions-five levels instrument, were estimated as part of a cost–utility analysis performed on an intention-to-treat cohort adopting a health payers perspective.

Results

Differences in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) over 7 days from baseline and at 24 hours in the dexamethasone compared with the placebo group (2.9% and 2.5% higher, respectively) were observed. After controlling for the baseline HRQoL imbalances, the economic impact of the intervention was not statistically significant: the quality-adjusted life year difference was −0.00005 (95% CI −0.0002 to 0.00011) equivalent to a loss in HRQoL of a half hour in the dexamethasone group. The average cost per patient associated in the dexamethasone and placebo groups in the basecase analysis was £73 and £69, respectively. In the basecase probabilistic analysis, the mean ICER was −£6440 (95% CI −£132 151 to £126 335) and the median ICER was −£304 (IQR-£5816 to £3877); suggesting considerable uncertainty.

Conclusions and relevance

The economic burden associated with sore throat is substantial and was estimated at £2.35 billion to the healthcare services payer based on reported resource use and 2015 UK unit costs. There is considerable uncertainty regarding the cost-effectiveness of a single dose of oral dexamethasone as a treatment strategy and therefore insufficient evidence to support its use in clinical practice.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN17435450; Post-results.

Keywords: cost-utility analysis, primary care, sore throat

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The analysis undertaken provides the first detailed account of the cost of sore throat in the UK.

The study collected a wide range of demographic, clinical, quality of life and resource use data using a trial-specific daily patient diary which permitted an extensive exploration of uncertainty in scenario and subgroup analyses.

Both health services payer and societal perspectives were assessed in the economic evaluation.

In contrast to previous research highlighting no clinical differences across delayed prescription and no treatment strategies, this analysis suggests that clinical and non-clinical benefits of the delayed prescription in addition to the dexamethasone need to be explored further.

Reported resource use for healthcare services payer perspective analysis was cross-checked with a follow-up patient survey and medical record review and as such where no resource use was identified for each patient across the data sources, the assumption of zero resource use for that category is justifiable but potentially leading to some bias in cost estimates.

Introduction

An estimated £400 million annually is spent on consultations and lost productivity associated with sore throat alone in the UK.1 2 Almost 1 in 10 registered UK patients will see their general practitioner (GP) every year with sore throat.3 Ninety-one per cent of those diagnosed with tonsillitis will receive antibiotics, as will half of those recorded as ‘sore throat’ or ‘pharyngitis’.4 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and International guidance recognises the limited evidence for benefit of antibiotics in its advice to avoid prescriptions in the majority of patients5 6; however, prescribing rates remain disproportionately high even though patients attend mainly due to anxiety over symptoms.7 A key driver for patients to attend with a sore throat is the severity of their symptoms, so affective symptomatic treatment may help reduce patient reliance on antibiotic. Furthermore where antibiotics are used for streptococcal infections more rapid clinical improvement is also plausible with steroids,8 which could facilitate shorter courses of antibiotics, which would improve both prescribing and the overall economic burden of sore throat. Further, negative externalities associated with overprescribing antibiotics, predominantly the increasing issue of antimicrobial resistance9 could also be moderated. The Treatment Options without Antibiotics for Sore Throat (TOAST) trial10 addressed whether or not oral corticosteroids provide clinical and cost-effective benefits through symptom relief of sore throat. The findings of the trial highlighted no clinical impact of a single dose of oral dexamethasone compared with placebo for resolution of symptoms at 24 hours; however, at 48 hours there was a significant improvement for patients receiving the intervention.11 The cost-effectiveness analysis alongside the TOAST trial assessed the costs and benefits of a single dose of 10 mg oral dexamethasone compared with placebo for the symptom relief of sore throat.

Methods

Intervention

TOAST was a multicentre, two-arm, individually randomised, double blind trial comparing a single dose of 10 mg oral dexamethasone with identical placebo in adults aged between 18 and 70 years1 inclusive, presenting to primary care with acute sore throat. Recruitment took place in 42 primary care clinics in England from April 2013 to February 2015. The intervention period assessed was 7 days postpresentation and participants were followed up for 28 days to assess resource use and adverse events. A subgroup of patients in each trial arm received a delayed prescription for antibiotics at the discretion of the GP and randomisation was stratified by this decision. Further details on trial design are published elsewhere. 6

Outcome measure

The cost-effectiveness analysis assessed quality-adjusted symptom resolution over the 7-day trial duration and estimated median time to complete resolution of symptoms and the corresponding utility gains measured by the EuroQol-five dimensions-five levels (EQ-5D-5L) index. These outcomes informed the construction of a quality-adjusted life year (QALY) used in the cost–utility analysis. The EuroQol instrument has five domains (mobility, self-care, activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) and five response levels ranging from no problems to severe problem.12 This health-related quality of life (HRQoL) instrument was administered to all participants at baseline and completed on each day of the 7-day patient diary. Each of the five dimensions in the EQ-5D-5L version is scored from 1 (no problem) to 5 (extreme problems), generating a profile (eg, 11 245) that can be used to calculate a single index score (range −0.281 to 1.000).13 The EQ-5D instrument also generates a self-rating of HRQoL scored from 0 to 100 employing a Visual Analogue Scale; this was used in scenario analyses. Quality-adjusted symptom resolution at 24 and 48 hours were also reported.

Resource use

Primary care resource utilisation was recorded in a trial patient diary for the first 7 days of the trial and was complemented by a follow-up survey sent to those with incomplete patient diaries. A primary care patient medical record review for the period from day 1 to day 28 (trial follow-up period) was also undertaken which recorded primary and secondary care contacts related to sore throat including serious adverse events (SAEs) related to the condition. SAEs included in the analysis were those classified as such by the trial protocol; and detailed in the main trial paper.11 Resource use included the following: visits and telephone calls to the GP; visits and telephone calls to nurses; out-of-hours calls and visits; pharmacy visits; calls to helpline ‘111’; accident and emergency (A&E) visits; hospitalisations and various types of reported medication including prescribed antimicrobials and over-the-counter (OTC) medications.

Unit costs

Total and average costs were estimated for the intervention, antibiotic usage (up to and including day 7), OTC medication usage (for days 0–7), health resource use/medication across the trial period (for days 1–28), SAEs and patient productivity losses associated with sick days reported (for work and education) and inability to carry out usual activities. Unit costs, presented in the (online supplementary file 1), were obtained from a number of sources including, Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU),14 British National Formulary,15 Boots Chemist16 and the National Health Service Electronic Tariff Database17 and are reported in UK currency. Productivity losses were costed using average wage rates for those employed and minimum wage rates for students.18 All cost estimates were reported in 2015 GBP using appropriate adjustments for prices retrieved where necessary.19 Disaggregated average cost estimates reported were based on the full cohort in the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis assuming non-responders had zero costs.

bmjopen-2017-019184supp001.pdf (661KB, pdf)

Analysis

Patient characteristics and reported resource use were summarised by trial arm. The primary economic analysis was conducted on an ITT basis and adopted the healthcare services payer perspective (HSP) which included the cost burden to the HSP only. Given the short-term duration of the trial, neither costs nor benefits were discounted. For the HSP the prescription administrative charge, normally applied to employed, working-age adults only in the UK,20 associated with the antimicrobial was not incorporated into the cost analysis as this was considered an out-of-pocket (OOP) expense borne by the patient; this was not considered as a contribution to the HSP either, that is, reducing the net cost of care per person to the HSP, as the prescription administrative charge is not applied to everyone and the full amount may not be recouped by the HSP.21 In the scenario analyses, a societal costing perspective (SCP) was also adopted reflecting the overall economic burden of the dexamethasone relative to the placebo. This included productivity losses due to sick days, that is, reported time off due to missed work or education and reported inability to carry out usual activities, and OOP expenses. Further scenarios assessed subgroups based on patient characteristics. The subgroup who highlighted they were current smokers at the time of the trial were assessed in a scenario analysis due to the extra healthcare burden smokers have relative to non-smokers.22 Descriptions of all 20 analyses are presented in the (online supplementary table A2).

Each element of costs and outcomes was reported separately, consistent with a cost–consequence analysis; the resource use reported was for the full ITT cohort (ie, no missing resource use data) and the HRQoL data reported in the disaggregated format was for complete cases, that is, n=337; 60% of the full cohort. Missing HRQoL data were assessed and classified as missing at random (see online supplementary appendix figure A1).16 Multiple imputation analysis was performed for missing outcome data (40%) in the ITT cohort using a number of imputations (n=60) greater than the proportion of missing data.23 The range of covariates included in the multiple imputation analysis along with a more comprehensive presentation of methods is presented (see online supplementary appendix table A3). The trial and follow-up duration was 28 days in total and for consistency it was assumed that HRQoL was unchanged from day 7 to day 28 using the last value brought forward technique.24 The average utility from baseline reported across the 28 days, calculated using area under the curve was considered 1/13th of a QALY. Baseline variation in outcomes was adjusted for incorporating multiple regression and seemingly unrelated regression techniques which estimated the baseline imbalance taking into account costs and effects.16 25 QALYs exhibited a non-normal distribution (see online supplementary appendix tables A4–A5) and bootstrapping techniques using 1000 iterations were applied in Microsoft Excel.26 The differences in EQ-5D-5L from baseline (day 0) at each day, that is, days 1–7 were estimated and results from the complete case analysis (n=337) and the ITT analysis (n=565) are presented in the (online supplementary appendix tables A4–A5). Cost–utility analysis was undertaken and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were estimated and reported for the basecase analysis and all scenario analyses. ICERs were probabilistic for the basecase analysis and deterministic for the series of scenarios estimated. The analysis was undertaken in Stata V.14.1.27 A cost-effectiveness plane and cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC) were constructed based on the bootstrapped sample means and net monetary benefit (NMB) was also assessed against a range of willingness to pay thresholds up to £100 000.28 NICE willingness to pay threshold of £20 000 was adopted as a decision rule to assess cost-effectiveness.27

Results

The ITT cohort (n=565) had 288 in the dexamethasone group and 277 in the placebo group; descriptive statistics are presented in table 1. The mean age of participants was 37 years and 75% were women. There was no significant clinical difference in median time to complete symptom resolution across trial arms with both displaying complete symptom resolution by day 4; however, there was a significant difference in symptom resolution at 48 hours.11 The changes in HRQoL over the 7 days highlight larger differences at baseline and at 24 hours with the dexamethasone group reporting 2.9% and 2.5% higher utility scores, respectively (see online supplementary appendix figures A3–A4). Differences start to diminish (<1.5%) from day 2 onwards. Table 2 highlights the differences in estimated QALYs for the imputed ITT cohort. After controlling for the baseline imbalances in HRQoL, the impact of the intervention was negative but not statistically significant: the QALY gain was −0.00005 (95% CI −0.0002 to 0.00011) equivalent to a loss in HRQoL of a half hour for the dexamethasone relative to the placebo group. Unadjusted differences in HRQoL for the ITT and complete case cohorts are presented (see online supplementary appendix figures A4–A5).

Table 1.

TOAST trial patient characteristics

| Placebo group |

Dexamethasone group |

|

| All eligible participants (ITT) | 277 (49%) | 288 (51%) |

| Male | 73 (13%) | 67 (12%) |

| Female | 204 (36%) | 221 (39%) |

| Mean age* | 37.3 (SD: 14.30) | 37.2 (SD: 14.36) |

| Current smoker | 51 (9%) | 52 (9%) |

| Antibiotic details† | ||

| Given delayed prescription | 108 (19%) | 115 (20%) |

| Reported taking antibiotics | 42 (7%) | 34 (6%) |

| Not given delayed prescription | 169 (30%) | 173 (31%) |

| Reported taking antibiotics | 16 (3%) | 16 (3%) |

| Total reported antibiotics usage | 58 (10%) | 50 (9%) |

| Resource use | ||

| Reported using OTC medicines (days 1–7) | 178 (32%) | 173 (31%) |

| Reported resource use (days 1–7) | 69 (12%) | 67 (12%) |

| Reported resource use in follow-up (days 8–28) | 20 (4%) | 30 (5%) |

| SAE‡ | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Other AE | 1 (<1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Employment status/sick days | ||

| Reported working FT (22 years and over) | 149 (26%) | 145 (26%) |

| Reported working PT (22 years and over) | 40 (7%) | 39 (7%) |

| Assumed in FT/PT education§ (18–21 years) | 28 (5%) | 33 (6%) |

| Unemployed | 60 (11%) | 71 (13%) |

| Sick days—proportion reporting >1 hour missing (days 0–7) | 104 (18%) | 89 (16%) |

| Sick days—proportion reporting >1 hour missing (days 1–7) | 72 (13%) | 60 (11%) |

| Usual activities—proportion reporting >1 hour missing (days 0–7) | 137 (24%) | 127 (22%) |

| Usual activities—proportion reporting >1 hour missing (days 1–7) | 98 (17%) | 104 (18%) |

Percentages in brackets represent proportion of full trial cohort (n=565).

*Mean age was estimated using the ITT population previous to the amendment to inclusion criteria constricting the upper age limit to 70 years. Fourteen patients were over 70 years evenly distributed across both arms.

†Antibiotics reported for ‘sore throat’ are included if prescribed within the 7-day trial period and were administered outside a secondary care setting. This deviates slightly from the clinical paper analysis classification of overall antibiotic use which included antibiotics administered in secondary care for one patient in the control group.

‡SAE’s included were categorised as ‘Suspected Serious Adverse Reaction’ in the clinical paper. Although three such events were reported, one was linked to a further SAE ultimately resulting in death and so was excluded from the economic analysis.

§Those aged 18–21 years reporting ‘yes’ to FT/PT work/education question in the baseline survey were all categorised into education for purposes of costing productivity losses in a scenario (see online supplementary appendix).

AE, adverse event; FT/PT, full time/part time; ITT, intention-to-treat; OTC, over-the-counter; SAE, serious adverse event; TOAST, Treatment Options without Antibiotics for Sore Throat.

Table 2.

Quality-adjusted life year (QALY) analysis

| Placebo (n=277*) Mean (SE) |

Dexamethasone (n=288*) Mean (SE) |

Difference (Dexamethasone -placebo) | P values | |

| Imputed unadjusted QALYS | 0.07165 (0.0006) | 0.07199 (0.0005) | 0.00034 (0.0009) | <0.000 |

| Imputed QALYs, adjusted for baseline differences | 0.07672 (0.0004) | 0.07677 (0.0005) | −0.00005 (0.00008) | 0.522 |

| Imputed QALYs for those given delayed prescription (adjusted) | 0.0743 (0.0005) | 0.0759 (0.0006) | 0.00155 (0.0001) | <0.000 |

| Imputed QALYs for those not given a delayed prescription (adjusted) | 0.0785 (0.0005) | 0.0770 (0.0007) | −0.00149 (0.0001) | <0.000 |

| Imputed QALYs with patients removed who experienced SAE or AE (adjusted) (n=562) | 0.0768 (0.0004) | 0.0767 (0.0005) | −0.00006 (0.00008) | 0.473 |

| Imputed QALYs with patients removed who were over 70 years (adjusted) (n=551) | 0.0766 (0.0004) | 0.0765 (0.0005) | −0.000123 (0.00008) | 0.128 |

| Imputed QALYs with patients who were current smokers only (adjusted) (n=103) | 0.0738 (0.0008) | 0.0768 (0.0010) | 0.00294 (0.00018) | <0.000 |

| Imputed QALYs at 24 hours, adjusted for baseline differences | 0.00270 (0.000008) | 0.00271 (0.000010) | 0.00001 (0.000002) | <0.000 |

| Imputed QALYs at 48 hours, adjusted for baseline differences in HRQoL | 0.00535 (0.000025) | 0.00538 (0.000031) | 0.00003 (0.000005) | <0.000 |

| Imputed QALYs at 48 hours, adjusted for baseline differences in HRQoL and RR of symptom resolution | 0.00492 (0.000024) | 0.00534 (0.000029) | 0.000422 (0.000005) | <0.000 |

*This sample size is based on 60 imputed datasets.

AE, adverse event; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; RR, relative risk; SAE, serious adverse event.

For the subgroup who received the delayed prescription based on clinical need, a statistically significant benefit was evidenced after baseline imbalances were adjusted for resulting in an approximate HRQoL gain of 13.6 hours relative to the control group. For the subgroup who did not receive the prescription, the dexamethasone group indicated a significant QALY loss of approximately 13 hours relative to the placebo group. For the patient group who reported that they were current smokers a significant QALY gain from the dexamethasone of 0.0029, equivalent to 1 day was evidenced. At 48 hours where a significant difference in the risk ratio of symptom resolution at 48 hours in favour of the dexamethasone (RR 1.31 (95% C, 1.02 to 1.68; p=0.03)) was observed, the significant QALY gain approximated to 3.7 hours for the current smokers subgroup.

The average cost per patient associated with the dexamethasone and placebo groups in the basecase analysis adopting a HSP was £73 and £69, respectively. Table 3 highlights total costs for the categories included in the economic evaluation. Average costs were higher across both trial arms for the subgroup who did not receive the delayed prescription relative to the subgroup who did (£24 and £18 higher in the placebo and dexamethasone groups, respectively) driven by higher health service utilisation; however, no statistically significant impact on costs across these subgroups for the HSP was found. For the SCP, including the cost associated with inability to carry out usual activities (Scenario I), the average cost per patient was £126 and £134 for the dexamethasone and placebo groups, respectively. This suggests a cost saving of £7 per patient to society. For the subgroup who received the delayed prescription, there was a negligible SCP reduction in the dexamethasone group of −£0.18; however, for those who did not receive the delayed prescription the SCP reduction for the substantial at −£12 signalling strong evidence of cost savings from the use of oral dexamethasone compared with placebo.

Table 3.

Cost analysis

| Cost bundle category | Description | Total cost 2015 £ | Average cost 2015 £ | ||||

| Placebo | Dexa-methasone | (Dex- placebo) |

Placebo | Dexa- methasone | (Dex- placebo) | ||

| Intervention | Cost associated with the intervention. | £12 188 | £14 124 | £1936 | £44 | £49.04 | £5.04 |

| Antibiotics—cohort A | Cost associated with antibiotics reported in patient survey, follow-up survey and medical records. | £164 | £138 | −£26 | £0.59 | £0.48 | −£0.11 |

| Antibiotics—cohort B | Cost associated with antibiotics reported in patient survey and medical records only. | £154 | £128 | −£26 | £0.55 | £0.44 | −£0.11 |

| Antibiotics—societal | Cost associated with antibiotics inclusive of the patient copayment for prescriptions. | £689 | £581 | −£108 | £2.49 | £2.02 | −£0.47 |

| Antibiotics B—societal | Cost associated with antibiotics inclusive of the patient copayment for prescriptions for cohort B. | £646 | £538 | −£108 | £2.33 | £1.87 | −£0.46 |

| Antibiotics—societal for workers | Cost associated with antibiotics inclusive of the patient copayment for prescriptions for workers only. | £623 | £474 | −£149 | £2.25 | £1.65 | −£0.60 |

| Antibiotics B—societal for workers | Cost associated with antibiotics inclusive of the patient copayment for prescriptions for workers only in cohort B. | £547 | £431 | −£116 | £1.98 | £1.50 | −£0.48 |

| Over-the-counter (OTC) | Cost associated with reported OTC in the patient diary and follow-up survey. | £668 | £648 | −£20 | £2.41 | £2.25 | −£0.16 |

| Resource use—patient diary | Cost associated with resource use reported in the patient diary. | £2639 | £2732 | £93 | £9.53 | £9.49 | −£0.04 |

| Resource use—follow-up survey | Cost associated with resource use reported in the follow-up survey. | £4082 | £4008 | −£74 | £14.74 | £13.92 | −£0.82 |

| Productivity losses—days 0–7 and follow-up | Cost of missed days due to illness reported in the patient diary and follow-up survey. | £22 668 | £19 469 | −£3199 | £81.83 | £67.60 | −£14.23 |

| Productivity losses (B)—days 0–7 and follow-up | Cost of missed days due to illness assuming all 18–21 year olds were in education. | £21 505 | £18 634 | −£2871 | £77.63 | £64.70 | −£12.93 |

| Productivity losses—days 1–7 and follow-up | Cost of missed days due to illness reported in the patient diary from day 1 and follow-up survey. | £14 846 | £12 699 | −£2147 | £53.59 | £44.09 | −£9.50 |

| Productivity losses (B)—days 1–7 and follow-up | Cost of missed days due to illness (from day 1) assuming all 18–21 year olds were in education. | £14 176 | £12 140 | −£2036 | £51.17 | £42.15 | −£9.02 |

| Usual activities—days 0–7 and follow-up | Cost associated with missing time due to illness for usual activities reported in the patient dairy and follow-up survey. | £4904 | £5052 | £148 | £17.70 | £17.54 | −£0.16 |

| Usual activities—days 1–7 and follow-up | Cost associated with missing time due to illness (from day 1) for usual activities reported in the patient dairy and follow-up survey. | £3444 | £3672 | £228 | £12.43 | £12.75 | £0.32 |

| Total HSP costs—primary analysis | £19 073 | £21 002 | £1929 | £68.86 | £72.92 | £4.07 | |

| Total HSP costs—without SAE’s/AEs (n=562) option (A) |

£15 610 | £18 349 | £2739 | £56.76 | £63.93 | £7.17 | |

| Total HSP costs— delayed prescription |

£5830 | £7119.00 | £1289 | £53.99 | £61.90 | £7.91 | |

| Total HSP costs— no delayed prescription |

£13 243 | £13 883 | £640 | £78.36 | £80.25 | £1.89 | |

| Total HSP costs— smokers only (n=103) |

£6059 | £2787 | −£3272 | £118.81 | £53.60 | −£65.21 | |

| Total SCP option (I) |

£37 076 | £36 409 | −£667 | £133.85 | £126.42 | −£7.43 | |

| Total SCP without SAE’s/AEs (n=562) | £33 012 | £33 726 | −£667 | £120.04 | £117.51 | −£2.53 | |

| Total SCP— delayed prescription |

£12 995 | £13 816 | £821 | £120.32 | £120.14 | −£0.18 | |

| Total SCP— no delayed prescription |

£24 081 | £22 593 | −£1488 | £142.49 | £130.59 | −£11.90 | |

| Total SCP— smokers only (n=103) |

£8739 | £3259 | −£5480 | £171.35 | £62.68 | −£108.67 | |

Cohort A has an additional eight patients included who reported antibiotic use in follow-up surveys only. Cohort B does not include these patients in keeping with the statistical analysis plan outlined for the clinical analysis.

AEs, adverse events; HSP, healthcare services payer perspective; SAE’s, serious adverse events; SCP, societal costing perspective.

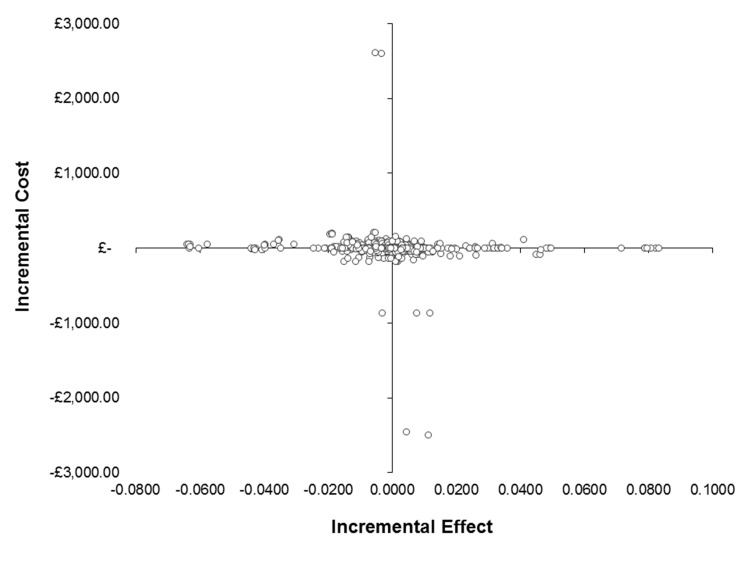

In the deterministic basecase analysis (table 4), the ICER was negative at −£81 400 due to the size and sign of the incremental effectiveness. In the basecase probabilistic analysis, the mean ICER was −£6440 (95% CI −£132 151 to £126 335) and the median ICER was −£304 (IQR: −£5816 to £3877); suggesting there is considerable uncertainty around this estimate. Several societal scenarios highlighted the potential for cost savings; however, due to outcome variability, there is insufficient evidence to suggest the dexamethasone is cost-effective. The cost-effectiveness plane (figure 1) presents a visual representation of the spread of the variation in cost and effect pairs for the basecase probabilistic analysis emphasising the wide variation in effectiveness. Due to this uncertainty, the CEAC (see online supplementary appendix figure A5) suggests the probability of cost-effectiveness is 47.9% at a £20 000 willingness to pay threshold. The mean NMB was £1.80 (SD: £351) at a £20 000 willingness to pay threshold with a 43.5% probability of the dexamethasone yielding a net benefit.

Table 4.

Cost–utility analysis (deterministic models)

| Scenarios* | Control | Intervention | ∆ in cost | ∆ in effect† | ICER | Interpretation‡ |

| Healthcare services payer perspective | ||||||

| Basecase | £68.86 | £72.92 | £4.07 | −0.00005 | −£81 400 | Not cost-effective |

| Scenario A | £56.76 | £63.93 | £7.17 | −0.00010 | −£71 700 | Not cost-effective |

| Scenario B | £69.22 | £73.37 | £4.15 | −0.00012 | −£33 850 | Not cost-effective |

| Scenario C | £53.99 | £61.90 | £7.92 | 0.00160 | £4950 | Cost-effective |

| Scenario D | £78.36 | £80.25 | £1.89 | −0.0015 | −£1260 | Not cost-effective |

| Scenario E | £57.58 | £77.18 | £19.60 | 0.0030 | £6533 | Cost-effective |

| Scenario F | £68.86 | £72.92 | £4.07 | 0.00001 | £407 000 | Not cost-effective |

| Scenario G | £68.86 | £72.92 | £4.07 | 0.00042 | £9690 | Cost-effective |

| Scenario H§ | £68.86 | £72.92 | £4.07 | −0.0038 | −£1071 | Not cost-effective |

| Societal cost perspective | ||||||

| Scenario I | £133.85 | £126.42 | −£7.43 | −0.00005 | £1 48 600 | Not cost-effective |

| Scenario J | £167.36 | 154.72 | −£12.64 | −0.00005 | £2 52 800 | Not cost-effective |

| Scenario K | £120.04 | £117.51 | −£2.53 | −0.00010 | £25 300 | Not cost-effective |

| Scenario L | £135.51 | £127.59 | −£7.92 | −0.00005 | £158 400 | Not cost-effective |

| Scenario M | £135.23 | £127.44 | −£7.79 | −0.00005 | £155 800 | Not cost-effective |

| Scenario N | £120.32 | £120.14 | −£0.18 | 0.00160 | −£112 | Cost-effective and cost saving |

| Scenario O | £142.49 | £130.59 | −£11.90 | −0.00150 | £7933 | Not cost-effective |

| Scenario P | £171.35 | £62.68 | −£108.67 | 0.0030 | −£36 223 | Cost-effective and cost saving |

| Scenario Q | £133.85 | £126.42 | −£7.43 | 0.00001 | −£743 000 | Cost-effective and cost saving |

| Scenario R | £133.85 | £126.42 | −£7.43 | 0.00042 | −£17 690 | Cost-effective and cost saving |

| Scenario S§ | £133.85 | £126.42 | −£7.43 | −0.0038 | £1955 | Not cost-effective |

*Full scenario details are presented in the (online supplementary file 1).

†Changes in effect have been adjusted for baseline differences for each model and are representative of an annual timeframe (see table 2 for more details).

‡Not cost-effective is suggested if the effect is negative and therefore the ICER is negative; not cost-effective may also be suggested when the ICER is positive due to both a negative cost and effect that is, positioned in the Southwest quadrant of the cost-effectiveness plane, depending on the WTP threshold. As the stated WTP threshold is £20 000 per QALY gain, all positive ICERs due to positive costs and effects that are over £20 000 are also deemed not cost-effective. Also note that CIs were not reported as the analysis are deterministic and non-linear; therefore CIs could not be meaningfully interpreted.

§Average unadjusted EQ-VAS scores across baseline to day 7 are presented in the (online supplementary appendix). After adjustments for imbalance at baseline, the incremental effect was negative at −0.174 at day 7. The change in effect presented in the table above has been adjusted to represent an annual timeframe consistent with cost per QALY interpretation.

EQ-VAS, EuroQol-Visual Analogue Scale; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; WTP, willingness to pay.

Figure 1.

Cost-effectiveness plane.

Discussion

The analysis undertaken provides the first detailed account of the cost of sore throat in the UK estimating that on average, costs of treating sore throat to the HSP are approximately £69 per patient and to society £134. With approximately 340 million consultations annually in the UK29 and 1 in 10 due to sore throat,4 the economic burden is estimated at £2.35 billion (or £4.56 billion to society) based on UK unit costs. The average cost difference was £4.07 (higher in the dexamethasone group): the dexamethasone group cost differential was £5.04, that is, the cost to the HSP of the single dose of oral dexamethasone. Therefore, from the HSP, there is insufficient evidence to suggest the intervention is cost-effective and there is some evidence to suggest the intervention may be producing a negative impact on HRQoL across the whole cohort.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The study collected a wide range of demographic, clinical, QoL and resource use data using a trial-specific daily patient diary which permitted an extensive exploration of uncertainty in scenario and subgroup analyses. Subgroup analysis indicated that for those who received the delayed antibiotic prescription and the dexamethasone versus those who received the delayed prescription and the placebo, the effect on HRQoL was positive and significant and therefore the resulting ICERs were cost-effective at £4950 per QALY gain. In contrast the placebo subgroup not given the delayed prescription had a significantly negative effect. GPs selected patients who were perceived to be in greater clinical need for the delayed prescription sub-arm of the trial; as this subgroup may have had increased severity of symptoms relative to their counterparts, they had more scope to improve from a clinical and HRQoL perspective which in part may explain the variation in HRQoL for the subgroups. Additionally, the average costs of those in the ‘no delayed prescription’ subgroup who received intervention or placebo were 30% and 45% times higher, respectively, than those in the comparative subgroup who received the delayed prescription. Cost differences observed across subgroups were primarily driven by higher reported health service use contacts across the trial and follow-up periods: 210% increase in the ‘no delayed prescription’ subgroups overall and 157% and 286% higher for the intervention and placebo arms, respectively. Caution is needed in interpreting this variation as the trial was not powered for subgroup analysis of resource use and response rates were low. Previous research did not find any clinical differences across delayed prescription and no treatment strategies30; however, our findings suggest that the clinical and non-clinical benefits of the delayed prescription in addition to the dexamethasone need to be explored further.

Although only a slight reduction in antibiotic usage was observed in the intervention arm relative to the placebo, that is, 3% less reported use for the delayed prescription subgroup, we feel the range of budgetary, clinical and environmental benefits of reducing antibiotic usage need to be explored further given the evidence highlighted in this study.

When assessing the impact of the dexamethasone on those who reported being current smokers (n=103, equally distributed between trial arms), there was a significant increase in HRQoL from baseline suggestive of cost-effectiveness for smokers: ICER £6533. Due to higher risk of prolonged symptoms compared with previous smokers or non-smokers, this intervention may provide an interactive anti-inflammatory perhaps akin to effects in patients with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, primarily caused by smoking.

Adoption of a SCP highlighted cost savings for the intervention relative to the control group. The main driver of difference in the range of scenarios adopting a SCP was the cost associated with missing work or education due to sickness. However, there were also differences in reported OTC medication usage across trial arms and subgroups that may influence recovery.

The study is not without its limitations. Missing data were an issue as the main tool for data collection was a patient completed diary at each day of the trial follow-up: HRQoL over the 7 days was 60% complete and the resource use reported in diaries was 62% complete. The initial response rate was much lower and a protocol amendment which allowed the use of incentives for patients who returned diaries was introduced. Reported resource use for HSP analysis was cross-checked with a follow-up patient survey and medical record review and as such where no resource use was identified for each patient across the data sources, the assumption of zero resource use for that category is justifiable but potentially leading to some bias in cost estimates. However, EQ-5D-5L data were collected from the patient survey only and missing data were considerable at 40%. Although robust multiple imputation techniques were applied to impute values, it is recognised that the range of covariates used to impute missing data may not reflect the degree of heterogeneity across the patient cohort and therefore some bias may remain in terms of the resource use and outcomes reported versus those that were not. If the imputation model was mis-specified, the imputation estimates could have some degree of bias.31 Due to the high uncertainty around observed HRQoL estimates across both arms, however, the limitations associated with multiple imputation are not cause for concern. In the analyses adopting a SCP, self-reported data on time unable to engage in usual activities and OTC medications purchased were not imputed for those with missing data and assumed zero for non-responders. The total cost burden to society is more than likely underestimated as a result and the SCP cost difference across both arms may not be as representative as the HCP cost difference.

Further limitations include the interpretation of the subgroup analyses given the small sample sizes and limitations of the data outlined. The findings based on the subgroup analyses should be interpreted with caution and need to be assessed with appropriately powered trials. However, the subgroup analyses give greater understanding of the wide variation in outcomes observed.

Conclusions and policy implications

In conclusion, sore throat has a substantial economic burden on healthcare delivery systems with this study estimating the economic burden from a HCP in the UK at £2.35 billion annually. More effective strategies for assessing and providing rapid symptom relief could reduce the cost burden as well as improve clinical and HRQoL outcomes. The findings of this study suggest there is considerable uncertainty in relation to the effectiveness and HRQoL benefit of dexamethasone for sore throat and therefore insufficient evidence to suggest cost-effectiveness or its adoption as a viable treatment strategy. However, there was evidence suggestive of potential benefits in several subgroups which could be investigated further in follow-up trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the full TOAST study team for their input: M Voysey, J Cook and J Allen, of Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, and K Harman of Department of Medicine, University of Southampton.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to: the conception and design of the TOAST trial analysis including guidance on the health economic evaluation; the drafting and revising of this manuscript; approval of the final version of the manuscript and are accountable for all aspects of the work presented. Each author has particular areas of expertise as follows: applied economic evaluation leads–RMB and JW (joint first authors), statistical analysis: SJ, NW and RP, project management, project conception, design and clinical lead:GH, clinical leadership and guidance, interpretation and policy interpretation: ADH, MT, CH, PL and MM. His research presents an honest, accurate and transparent account of the economic evaluation of the TOAST UK study; no relevant aspects of the study have been omitted and the wide range of scenario analyses addresses both the clinical heterogeneity and variability in structural assumptions.

Funding: This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research (Project number 172).

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the NHS or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None decalred.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The research protocol was approved by the National Research Ethics Committee South Central (12/SC/0684).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There is no additional data available for this study.

Collaborators: Voysey M, Cook J, Allen J, Harman K

Contributor Information

The TOAST Trial Investigators:

References

- 1. Roos K, Claesson R, Persson U, et al. The economic cost of a streptococcal tonsillitis episode Scandinavian. Journal of Primary Healthcare 1995;13:257–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fourth national Study HMSO. HMSO Morbidity Statistics in General practice: Fourth national Study HMSO. 1994.

- 3. Gulliford M, Latinovic R, Charlton J, et al. Selective decrease in consultations and antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory tract infections in UK primary care up to 2006. J Public Health 2009;31:512–20. 10.1093/pubmed/fdp081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Del Mar CB GPP, Spinks AB. Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews 2006;4:CD000023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. NICE guideline. Respiratory Tract Infections - antibiotic prescribing. Prescribing of antibiotics for self-limiting respiratory tract infections in adults and children in primary care. UK: National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Get Smart: Know When Antiobiotics Work in Doctor’s Offices: Adult Treatment Recommendations. https://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/community/for-hcp/outpatient-hcp/adult-treatment-rec.html 2017. (accessed 19 Jun 2017).

- 7. Gulliford MC, Dregan A, Moore MV, et al. Continued high rates of antibiotic prescribing to adults with respiratory tract infection: survey of 568 UK general practices. BMJ Open 2014;4:. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hayward G, Thompson M, Heneghan C, et al. Corticosteroids for pain relief in sore throat: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2009;339:b2976 10.1136/bmj.b2976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, et al. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;340:c2096 10.1136/bmj.c2096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cook J, Hayward G, Thompson M, et al. Oral corticosteroid use for clinical and cost-effective symptom relief of sore throat: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014;15:365 10.1186/1745-6215-15-365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hayward GN, Hay AD, Moore MV, et al. Effect of oral dexamethasone without immediate antibiotics vs placebo on acute sore throat in adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;317:1535–43. 10.1001/jama.2017.3417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Devlin NJ, Krabbe PF. The development of new research methods for the valuation of EQ-5D-5L. Eur J Health Econ 2013;14:1–3. 10.1007/s10198-013-0502-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Devlin NJ, Shah KK, Feng Y, et al. Valuing health-related quality of life: an EQ-5D-5L value set for England. Health Econ 2018;27 10.1002/hec.3564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. PSSRU Unit Costs of Health and Social Care. Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2015. 2015. http://www.pssru.ac.uk/project-pages/unit-costs/2015/

- 15. British Medical Association. British National Formulary. UK: British Medical Association, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boots. Boots online pharmacy. 2015. www.boots.com

- 17. Governance of UK. Department of Health Reference Cost 2014/2015. London: Governance of UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Office of National Statistics. Annual survey of hours and earnings. 2014. www.ons.gov.uk (accessed 6 Jun 2017).

- 19. Office of National Statistics. Consumer price inflation index. 2015. www.ons.gov.uk (accessed 6 June 2017).

- 20. Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. Exemptions from the prescription charge. 2016. http://psnc.org.uk/dispensing-supply/receiving-a-prescription/patient-charges/exemptions/ (accessed 9 Jun 2017).

- 21. NHS Choices. NHS in England- help with health costs. 2017. http://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/Healthcosts/Pages/Prescriptioncosts.aspx

- 22. Wacker M, Holle R, Heinrich J, et al. The association of smoking status with healthcare utilisation, productivity loss and resulting costs: results from the population-based KORA F4 study. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:278 10.1186/1472-6963-13-278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Faria R, Gomes M, Epstein D, et al. A guide to handling missing data in cost-effectiveness analysis conducted within randomised controlled trials. Pharmacoeconomics 2014;32:1157–70. 10.1007/s40273-014-0193-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hunter RM, Baio G, Butt T, et al. An educational review of the statistical issues in analysing utility data for cost-utility analysis. Pharmacoeconomics 2015;33:355–66. 10.1007/s40273-014-0247-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Manca A, Hawkins N, Sculpher MJ. Estimating mean QALYs in trial-based cost-effectiveness analysis: the importance of controlling for baseline utility. Health Econ 2005;14:487–96. 10.1002/hec.944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Glick HA, Doshi JA, Sonnad SS, et al. Economic evaluation in clinical trials: handbooks in health economics. 2 Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27. StataCorp. Stata statistical software. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28. NICE. Guide to methods of technology appraisal. Manchester: NICE, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29. British Medical Association (BMA). General Practice in the UK – background briefing. 2017. https://www.bma.org.uk/-/media/files/pdfs/./general-practice.pdf?la=en (accessed 19 Jun 2017).

- 30. Little P, Moore M, Kelly J, et al. Delayed antibiotic prescribing strategies for respiratory tract infections in primary care: pragmatic, factorial, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2014;348:g1606 10.1136/bmj.g1606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Horton NJ, Kleinman KP. Much ado about nothing: a comparison of missing data methods and software to fit incomplete data regression models. Am Stat 2007;61:79–90. 10.1198/000313007X172556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-019184supp001.pdf (661KB, pdf)