Abstract

Objectives

To identify the shared priorities for future research of women affected by and clinicians involved with pessary use for the management of prolapse.

Design

A priority setting project using a consensus method.

Setting

A James Lind Alliance Pessary use for prolapse Priority Setting Partnership (JLA Pessary PSP) conducted from May 2016 to September 2017 in the UK.

Participants

The PSP was run by a Steering Group of three women with experience of pessary use, three experienced clinicians involved with management of prolapse, two researchers with relevant experience, a JLA adviser and a PSP leader. Two surveys were conducted in 2016 and 2017. The first gathered questions about pessaries, and the second asked respondents to prioritise a list of questions. A final workshop was held on 8 September 2017 involving 10 women and 13 clinician representatives with prolapse and pessary experience.

Results

A top 10 list of priorities for future research in pessary use for prolapse was agreed by consensus.

Conclusions

Women with experience of pessary use and clinicians involved with prolapse management have worked together to determine shared priorities for future research. Aligning the top 10 results with existing research findings will highlight the gaps in current evidence and signpost future research to areas of priority. Effective dissemination of the results will enable research funding bodies to focus on gathering the evidence to answer the questions that matter most to those who will be affected.

Keywords: pelvic organ prolapse, pessaries, health priorities, consensus

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first UK equal collaboration of women and clinicians with experience of prolapse and pessary use to achieve consensus on the priorities for future research.

The James Lind Alliance uses a rigorous and transparent method enhancing the confidence that funding bodies can have in the results.

The use of an online survey as the main method for gathering questions for this Priority Setting Partnership may mean that not all groups of women with prolapse and pessary experience were accessed and that some groups may be under-represented in respect of the UK demographic.

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse is prevalent and costly and estimated to affect 30%–50% of all women who have had a vaginal delivery.1 2 Pessary use is widespread, and inexpensive but has a limited evidence base.3

Symptomatic prolapse is defined as a downward displacement of the pelvic organs (bladder, bowel or uterus) or vaginal apex from the normal anatomical position and is associated with feelings of vaginal heaviness or bulge.4 Additional symptoms may include difficulties with emptying the bladder and bowel, leakage of urine and faeces and problems with sexual activity.

Treatment options for women with prolapse include pelvic floor muscle exercises, a vaginal pessary device and surgery. A pessary is a silicone or plastic device of a supportive or space-occupying design that is positioned within the vagina to provide anatomical correction and support of the prolapsed compartment with the aims of reducing symptoms. A pessary is usually fitted in an outpatient clinic, left in situ for 4–6 months and then removed and replaced by a healthcare professional. Some women are taught to self-manage their pessary removing and replacing it as required.

Vaginal devices for prolapse have been in use since the time of the Ancient Egyptians,5 and published surveys suggest that currently up to 85% of gynaecologists use a pessary in the first-line management of prolapse,6–8 with 70 000 National Health Service (NHS) pessary procedures recorded in NHS data 2015–2016 (Sources: Information Services Division, NHS Scotland; HES data accessed 16 April 2017).

Despite the high prevalence of pessary use for prolapse there is limited evidence for their use, no UK-wide training for pessary fitting or management or information guidelines available for healthcare professionals or women with prolapse. The 2013 Cochrane review, ‘Pessaries (mechanical devices) for Pelvic Organ Prolapse in Women’ identified only one eligible randomised controlled trial with a maximum of seven trials being considered for the ongoing update9 (Bugge 2018, personal communication).

Understanding the research priorities in pessary use for prolapse for those who will be affected will help build the evidence for the conservative treatment of prolapse. This report presents the results of the first collaboration of women with pessary experience and clinicians involved with pessary provision for prolapse in a James Lind Alliance (JLA) Priority Setting Partnership (PSP). The top 10 priorities are presented.

Objective

We sought to determine the shared priorities for future research for women with experience of prolapse and pessaries, and healthcare professionals involved in the management of prolapse and fitting of pessaries.

Method

The JLA was established in 2004 to bring together healthcare professionals and service users affected by a condition in PSPs to determine the shared priorities for future research. Further information about the JLA methodology is available in the JLA guidebook.10

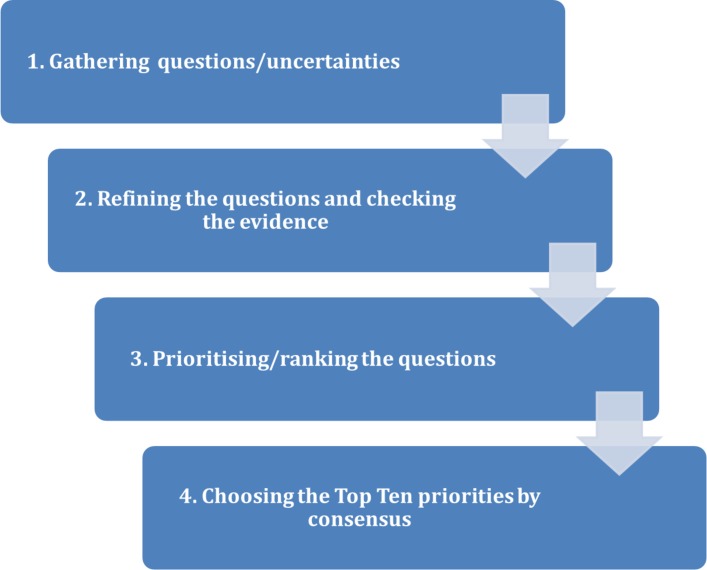

A Pessary use for prolapse PSP was established in May 2016 bringing together for the first time women with experience of prolapse and pessary use and healthcare professionals with experience of the provision and fitting of pessaries. The Steering Group (SG) comprised three women with pessary experience, three clinicians experienced in managing prolapse with pessaries, two researchers and a pessary company representative; this group agreed the terms of reference and protocol for the PSP with guidance from the JLA adviser and project leader (KL). The JLA method for the Pessary use for prolapse PSP involved four stages (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the James Lind Alliance (JLA) Priority Setting Partnership (PSP) process.

Patient and public involvement

Women with experience of prolapse and pessary use were central to this project from the inception with the underpinning principles of a JLA PSP including a requirement for the ‘balanced inclusion of patient, carer and clinician interests and perspectives.’10

At each stage of the process, women were equal partners in the design and decisions including the SG, survey design and piloting, survey participation and the final workshop. All survey participants were able to indicate a desire for further involvement and for information about the results. A results summary will be sent to all those who have left contact details, and more broadly posted on the relevant websites and Facebook groups.

Gathering questions/uncertainties

Healthcare professionals, women with experience of prolapse and pessaries and researchers were targeted to gather their questions. A short survey was designed and piloted asking participants to submit up to three questions or uncertainties on any aspect of pessaries. Survey respondents were assured that there was no correct question and any uncertainty that they felt mattered to them was acceptable. The survey was launched online and promoted on social media to relevant organisations, professional bodies, health-related websites and forums for women with prolapse. Paper copies of the survey were distributed to four urogynaecology clinics in the UK for patients and healthcare professionals to complete. The JLA PSPs do not require ethical approval for distribution of surveys but local R&D approval was gained for each site. Relevant conferences and professional meetings were also targeted and attendees asked to access the survey online. A total of 210 completed responses were received with comparable representation from women and HCPs (table 1). Questions (n=669) were extracted from responses to the survey (n=530), online forums (n=59) and a review of the literature (n=80).

Table 1.

First survey demographics*

| Participant category | Age range (years) | Pessary experience |

| 210 complete responses (166 online and 44 paper responses) from: | ||

| Women (n=71) | 30–89 | 72% had experience of current or previous pessary use ranging from ‘less than 2 weeks’ to ‘over 5 years’ |

| HCPs (n=87) | 18–69 | 61% with experience of fitting pessaries |

| Those identifying as being both HCP and a woman with experience of prolapse (n=27) | 18–89 | 74% had experience of fitting pessaries 44% had used a pessary for ranging from ‘2 weeks to 6 months’ and ‘over 5 years’ |

| Carers (n=5) | 30–69 | |

| Other respondents (n=17) included researchers, women with an interest in prolapse, Pilates teachers | ||

*Three missing values.

HCP, healthcare professional.

Refining the questions and checking the evidence

The PSP SG refined and checked the 669 questions. No individual uncertainties were discarded, and a record of the origin of all the questions was kept.

Submitted questions not within the scope of the previously agreed PSP terms of reference including comments were collated and documented but not taken forward (n=51). Three SG pairs were formed of a woman with pessary experience and a clinician experienced in pessary provision. The pairs worked with the PSP project leader to combine and refine the remaining 618 submissions into 66 indicative questions which reflected the overall inference of the source questions. These were grouped into the following question categories: ‘fit’, ‘sex’, ‘choice’, ‘who’, ‘risk’, ‘oestrogen’, ‘timing’, ‘care’ and ‘training’.

We applied the JLA definition of a treatment uncertainty10:

No up-to-date, reliable systematic reviews of research evidence addressing the uncertainty about the effects of treatment exist.

Up-to-date systematic reviews of research evidence show that uncertainty exists.

A systematic scoping review undertaken by the author (KL) with a search conducted from 2000 to 2016 (updated 2018) identified several trials relevant to the submitted questions which were shared with the SG but it was agreed that none of the gathered questions had been answered sufficiently by existing research and that all the questions submitted to the Pessary use for prolapse PSP were genuine uncertainties.3 11–16

Prioritising/ranking the questions

A prioritising survey was launched in June 2017 asking healthcare professionals and women with experience of prolapse to choose their personal top 10 questions from the 66 questions presented in the survey. The survey was distributed and promoted using the same methods as the first, with seven urogynaecology clinics for the paper surveys. Additionally, the project leader (KL) presented the survey to an Asian Women’s Support Group meeting to identify the group’s priorities. Two hundred and seventy-eight responses were received (table 2). The number of times each question occurred in respondents’ top 10 was counted. The questions were then ranked on the basis of that count to show the order of priority of the 66 questions and the SG then agreed the top 25 questions to go forward to the final workshop.

Table 2.

Second survey demographics

| Participant category | Age range (years) | Pessary experience |

| 278 completed responses (255 online and 23 paper responses) from: | ||

| Women (n=114) | 18—‘over 80’ | 58% with experience of pessary use ranging from ‘less than 2 weeks’ to ‘over 5 years’ 9% having refused a pessary |

| HCPs (n=76) | 18–80 | 92% treating women with prolapse 38% fitting pessaries |

| Those identifying as being both HCP and a woman with experience of prolapse (n=26) | 77% in the age range ‘31–59’ | 96% with personal experience of pessary use 15% fitting pessaries 69% treating women with prolapse |

| Other (n=11) including carers, retired HCPs, researchers and Pilates instructors | 31–80 | |

| Did not indicate demographics (n=52) | ||

HCP, healthcare professional.

Choosing the top 10 priorities by consensus

A final consensus workshop day was held on 8 September 2017 involving 23 participants purposively selected with small group discussions being facilitated by three JLA advisers. The participants included a general practitioner (GP), specialist urogynaecology clinicians with a varied level of pessary fitting experience, specialist pelvic health physiotherapists and women within an age range of 30 to over 80 years with a wide variety of personal experience of pessary use for prolapse. There were 10 women and 13 healthcare professionals. In advance of the final workshop the participants were sent the top 25 questions from the prioritising survey with no indication of the priority order, and asked to consider their top and bottom three questions for discussion on the day.

The JLA have adopted a modified nominal group technique (NGT) to achieve consensus in the final workshops. NGT has the advantage of being a well-established method, which works well in situations where there may be a concern about the strength of individual voices, where the topic may be contentious and where an outcome needs to be decided within a short time frame. The use of the NGT and a purposively selected group reduced the risk of bias in the final outcome. No new questions are generated in the final workshop.

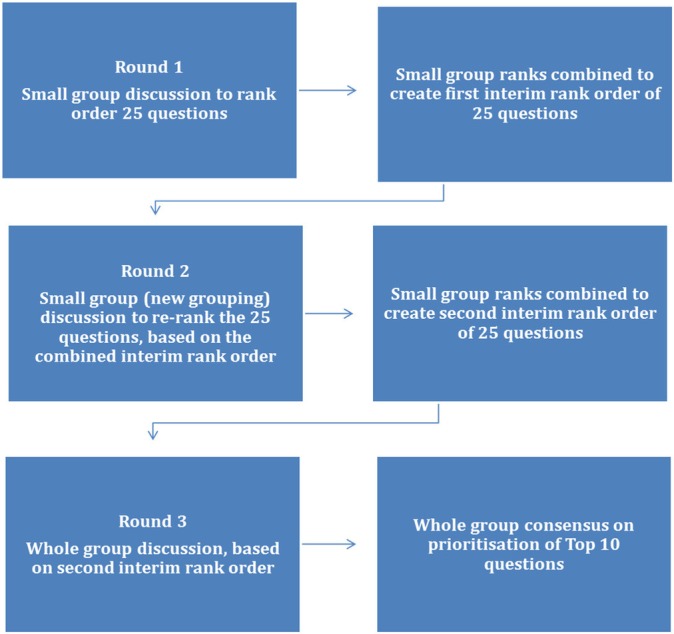

As illustrated in the flow chart (figure 2) a series of small group discussions and rankings were held. The interim rank orders from the small groupings were reverse scored each time to produce new rankings. The combined rankings from the small group sessions were then used to determine the ranked list of 25 questions that was then presented to the whole group for facilitated discussion to reach a final consensus on prioritisation of the top 10 questions.

Figure 2.

James Lind Alliance (JLA) Pessary Priority Setting Partnership (PSP) final workshop flow chart.

Results

The final top 10 priorities for future research in pessary use for prolapse indicate that sexual activity and psychological well-being are of key importance for healthcare professionals and women. The top 10 includes questions about self-management, pessary fitting and training, managing complications and the effectiveness of pessaries (box 1).

Box 1. The final top 10 research priorities for pessary use for prolapse.

How might a pessary affect sexual activity?

Do pessaries have an effect on the psychological well-being of women?

What is important for a pessary self-management programme?

What are the risks and complications of pessary use for prolapse?

Are pessaries effective as a long-term treatment for prolapse?

What is the best way to assess what type and size of pessary to use?

What is the best way to minimise and treat vaginal discharge caused by pessaries?

Does pessary use in prolapse have a positive impact on physical activity?

When should oestrogen cream be used with a pessary?

What is the ideal training to be a ‘qualified’ pessary practitioner?

Discussion

This PSP has brought together for the first time women and healthcare professionals with personal and professional experience of pessaries to ensure a collaborative and inclusive approach in which all participants had equal voice. In order to maximise the chance that future research projects will provide evidence for pessary use and enable optimal care for women with prolapse, it is essential that the research questions concern the priorities of women and healthcare professionals who will be affected, and that women are partners at each stage of the research. This Pessary use for prolapse PSP has established the priority questions for future research which will be disseminated widely to ensure that research funding bodies are made aware of what matters most to those affected. The JLA collaboration with the National Institute of Health Research is key to this outcome.

This JLA Pessary use for prolapse PSP is part of a doctoral research project that will continue with the results of the PSP being mapped to the current literature to identify those priority areas where existing research has addressed the topic, and to reveal the information, research and evidence gaps for the top 10 priorities.

The strengths of this project were:

A unique collaboration of women and clinicians with experience of prolapse to achieve consensus on the priorities for future research.

The use of a rigorous and transparent method with the JLA enhancing the validity of the process and increasing the likelihood of the future research agenda being targeted to those for whom it matters.

The use of social media and an anonymous online survey minimised the risk of stigma and embarrassment affecting participation.

There were limitations which should be acknowledged:

The use of an online survey may have introduced a bias in favour of those women who use the internet and social media.

Time and cost constraints reduced the number of clinical sites where women already receiving pessary care and their carers could have been targeted more effectively.

Despite extensive attempts to ensure representation from GPs and women from ethnically diverse groups, there may be under-representation in these sectors.

All the unanswered questions generated by this PSP will be available on the JLA website and widely disseminated to research commissioners, public health bodies and research funders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This PSP would not have been possible without the help and support of all the members of the Steering Group and the JLA adviser, Catherine White, and all those who completed the surveys.

Footnotes

Contributors: KL conducted the JLA PSP and wrote the manuscript. SH, DM and AP conceived the project and were involved in preparing the final manuscript. SH was a member of the Steering Group.

Funding: The JLA Pessary PSP was partially funded by a UK Continence Society (UKCS) research grant, two grants from the Pelvic Obstetric and Gynaecological Physiotherapy group (POGP) of the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy and a funded studentship from Glasgow Caledonian University.

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in the study design.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All survey data and a list of all submitted questions from the PSP will be available on the James Lind Alliance website with no access restrictions (http://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/priority-setting-partnerships/).

References

- 1. Hendrix SL, Clark A, Nygaard I, et al. Pelvic organ prolapse in the Women’s Health Initiative: gravity and gravidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;186:1160–6. 10.1067/mob.2002.123819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gyhagen M, Bullarbo M, Nielsen TF, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse 20 years after childbirth: a national cohort study in singleton primiparae after vaginal or caesarean delivery. BJOG 2013;120:152–60. 10.1111/1471-0528.12020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Panman CMCR, Wiegersma M, Kollen BJ, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of pessary treatment compared with pelvic floor muscle training in older women with pelvic organ prolapse. Menopause 2016;23:1307–18. 10.1097/GME.0000000000000706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haylen BT, Maher CF, Barber MD, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) / International Continence Society (ICS) Joint Report on the Terminology for Female Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP). Neurourol Urodyn 2016;35:137–68. 10.1002/nau.22922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oliver R, Thakar R, Sultan AH. The history and usage of the vaginal pessary: a review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2011;156:125–30. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.12.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gorti M, Hudelist G, Simons A. Evaluation of vaginal pessary management: a UK-based survey. J Obstet Gynaecol 2009;29:129–31. 10.1080/01443610902719813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pott-Grinstein E, Newcomer JR. Gynecologists' patterns of prescribing pessaries. J Reprod Med 2001;46:205–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cundiff GW, Weidner AC, Visco AG, et al. A survey of pessary use by members of the American urogynecologic society. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95(Pt 1):931–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bugge C, Ej A, Gopinath D, et al. Pessaries (mechanical devices) for pelvic organ prolapse in women (Review) summary of findings for the main comparison. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cowan K, Oliver S. The James Lind Alliance guidebook. 6th Ed Oxford, England: James Lind Alliance, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lough K. A systematic review of the use of pessaries for the management of pelvic organ prolapse in women [Internet]. PROSPERO CRD42016046793. 2016;3:1 http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42016046793. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cheung RYK, Lee JHS, Lee LL, et al. Vaginal pessary in women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2016;128:73–80. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Taege SK, Adams W, Mueller ER, et al. Anesthetic cream use during office pessary removal and replacement. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2017;130:190–7. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Meriwether KV, Komesu YM, Craig E, et al. Sexual function and pessary management among women using a pessary for pelvic floor disorders. J Sex Med 2015;12:2339–49. 10.1111/jsm.13060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cundiff GW, Amundsen CL, Bent AE, et al. The PESSRI study: symptom relief outcomes of a randomized crossover trial of the ring and Gellhorn pessaries. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;196:405.e1–405.e8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brazell HD, O’Sullivan DM, Forrest A, et al. Effect of a decision aid on decision making for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2015;21:231–5. 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.