Abstract

We demonstrate a method for the synthesis of NixNb1-xO catalysts with sponge-like and fold-like nanostructures. By varying the Nb:Ni ratio, a series of NixNb1-xO nanoparticles with different atomic compositions (x = 0.03, 0.08, 0.15, and 0.20) have been prepared by chemical precipitation. These NixNb1-xO catalysts are characterized by X-ray diffraction, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, and scanning electron microscopy. The study revealed the sponge-like and fold-like appearance of Ni0.97Nb0.03O and Ni0.92Nb0.08O on the NiO surface, and the larger surface area of these NixNb1-xO catalysts, compared with the bulk NiO. Maximum surface area of 173 m2/g can be obtained for Ni0.92Nb0.08O catalysts. In addition, the catalytic hydroconversion of lignin-derived compounds using the synthesized Ni0.92Nb0.08O catalysts have been investigated.

Keywords: Chemistry, Issue 132, chemical precipitation, catalysts, nanostructures, nanosheets, hydrodeoxygenation, lignin

Introduction

The preparation of nanocomposites has received increasing attention due to their crucial application in various field. To prepare Ni-Nb-O mixed oxide nanoparticles,1,2,3,4,5,6 different methods have been developed such as dry mixing method,7,8 evaporation method,9,10,11,12,13 sol gel method,14 thermal decomposition method,15 and auto-combustion.16 In a typical evaporation method9, aqueous solutions containing the appropriate amount of metal precursors, nickel nitrate hexahydrate and ammonium niobium oxalate were heated at 70 °C. After the removal of solvent and further drying and calcination, the mixed oxide was obtained. These oxide catalysts exhibit excellent catalytic activity and selectivity towards the oxidative dehydrogenation (ODH) of ethane, which is related to the electronic and structural rearrangement induced by the incorporation of niobium cations in the NiO lattice.11 The insertion of Nb drastically decreases the electrophilic oxygen species, which is responsible for the oxidation reactions of ethane12. As a result, extensions of this method have been done on the preparation of different types of mixed Ni-Me-O oxides, where Me = Li, Mg, Al, Ga, Ti and Ta.13 It is found that the variation of metal dopants could alter the unselective and electrophilic oxygen radicals of NiO, thus systematically tune the ODH activity and selectivity towards ethane. However, generally the surface area of these oxides is relatively small (< 100 m2/g), due to the extended phase segregation and formation of large Nb2O5 crystallites, and thus hampered their uses in other catalytic applications.

Dry mixing method, also known as the solid-state grinding method, is another commonly used method to prepare the mixed-oxide catalysts. Since the catalytic materials are obtained in a solvent-free way, this method provides a promising green and sustainable alternative to the preparation of mixed-oxide. The highest surface area obtained by this method is 172 m2/g for Ni80Nb20 at calcination temperature of 250 °C.8 However, this solid-state method is not reliable as reactants are not well mixed on the atomic scale. Therefore, for better control of chemical homogeneity and specific particle size distribution and morphology, other suitable methods to prepare Ni-Nb-O mixed oxide nanoparticles are still being sought.7

Among various strategies in the development of nanoparticles, chemical precipitation serves as one of the promising methods to develop the nanocatalysts, since it allows the complete precipitation of the metal ions. Also, nanoparticles of higher surface areas are commonly prepared by using this method. To improve the catalytic properties of Ni-Nb-O nanoparticles, we herein report the protocol for the synthesis of a series of Ni-Nb-O mixed oxide catalysts with high surface area by chemical precipitation method. We demonstrated that the Nb:Ni molar ratio is a crucial factor in determining the catalytic activity of the oxides towards the hydrodeoxygenation of lignin-derived organic compounds. With high Nb:Ni ratio above 0.087, inactive NiNb2O6 species were formed. Ni0.92Nb0.08O, which had the largest surface area (173 m2/g), exhibits fold-like nanosheets structures and showed the best activity and selectivity towards the hydrodeoxygenation of anisole to cyclohexane.

Protocol

Caution: For the proper handling methods, properties and toxicities of the chemicals described in this paper, refer to the relevant material safety data sheets (MSDS). Some of the chemicals used are toxic and carcinogenic and special cares must be taken. Nanomaterials may potentially pose safety hazards and health effects. Inhalation and skin contact should be avoided. Safety precaution must be exercised, such as performing the catalyst synthesis in the fume hood and catalyst performance evaluation with autoclave reactors. Personal protective equipment must be worn.

1. Preparation of Ni0.97Nb0.03O Catalysts where Nb:(Ni+Nb) molar ratios equal to 0.03

Combine 0.161 g of niobium (V) oxalate hydrate with 2.821 g of nickel nitrate in 100 mL of deionized water in a 250-mL three-necked round bottom flask equipped with a stir bar.

Stir the solution at 50 rpm and 70 °C to dissolve the compounds until the disappearance of precipitate using a heating magnetic stirrer.

Raise the temperature rapidly to 80 °C at a rate of 2 °C/min.

Add a mixed basic solution [aqueous ammonium hydroxide (50 mL, 1.0 M) and sodium hydroxide (50 mL, 0.2 M)] into the reaction mixture dropwise until the pH of the Ni/Nb solution reaches 9.0.

While stirring the reaction mixture, raise the temperature to 120 °C at 2 °C/min.

Stir the reaction mixture overnight at 50 rpm at 120 °C until the complete disappearance of the green color of the solution.

Perform inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) analysis for the solution to evaluate the concentration of remaining Ni2+ and Nb5+ ions in the solution and ensure the complete precipitation of remaining nickel nitrate.

Collect the solid by filtration using Büchner flask. Wash the solid by adding 2 L deionized water repeatedly within 20 min to remove the residual Na+ cation.

Collect the solid in a watch glass. Dry the solid at 110 °C for 12 h in dry oven.

Calcine by heating the solids in synthetic air (20 mL/min O2 and 80 mL/min N2) at 450 °C for 5 h in tube furnace. Check all glassware for defect prior to use the high temperature of reaction.

After the calcination, obtain 1 g of Ni0.97Nb0.03O catalyst. Use appropriate protective equipment such as safety glasses, gloves, lab coat, and fume hood to perform the nanocrystal reaction due to potential safety hazards and health effects of the nanomaterials.

2. Preparation of Ni0.92Nb0.08O Catalysts where Nb:(Ni+Nb) molar ratios equal to 0.08

- This procedure is similar to that of 1 except for the first two steps:

- Dissolve 0.43 g of niobium (V) oxalate hydrate in 100 mL of deionized water.

- Separately, dissolve 2.675 g of nickel nitrate in 100 mL of deionized water.

3. Preparation of Ni0.85Nb0.15O Catalysts where Nb:(Ni+Nb) molar ratios equal to 0.15

- The procedure is similar to that of 1 except for the first two steps:

- Dissolve 0.807 g of niobium (V) oxalate hydrate in 100 mL of deionized water.

- Separately, dissolve 2.472 g of nickel nitrate in 100 mL of deionized water.

4. Preparation of Ni0.80Nb0.20O Catalysts where Nb:(Ni+Nb) molar ratios equal to 0.20

- The procedure is similar to that of 1 except for the first two steps:

- Dissolve 1.076 g of niobium (V) oxalate hydrate in 100 mL of deionized water.

- Separately, dissolve 2.326 g of nickel nitrate in 100 mL of deionized water.

5. Preparation of Nb2O5 using chemical precipitation method

Calcine niobic acid (Nb2O5·nH2O) in synthetic air for 5 h at 450 °C to obtain pure Nb2O5 particles. NOTE: Confirm the completion of reaction using X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) analysis, where Nb2O5·nH2O is Amorphous and Nb2O5 is crystalline. According to the analysis, the calcination for 5 h at 450 °C was enough to complete the reaction.

6. Synthesis of β-O-4 lignin model compound, 2-(2-methoxyphenoxy)-1-phenylethan-1-one

Dissolve bromoacetophenone (9.0 g, 45 mmol) and 2-methoxyphenol (6.6 g, 53 mmol) in 200 mL of dimethylformamide (DMF) in a 500-mL conical flask with a magnetic stirrer. Use appropriate protective equipment and fume hood to perform the reaction using corrosive and carcinogenic chemicals and reagents.

Mix the above DMF solution with potassium hydroxide (3.0 g, 53 mmol) and stir the mixture overnight at 50 rpm at room temperature using magnetic stirrers.

Extract the product with the mixture solution of 200 mL of H2O and 600 mL of diethyl ether (1:3, v/v) using separation funnel. Obtain the upper diethyl ether layer of the solution.

Add MgSO4 (10 g) to absorb moisture of the diethyl ether solution. Filter the MgSO4 to obtain the diethyl ether solution by using filter paper and funnel.

After removal of the diethyl ether solution under reduced pressure at 0.08 MPa using rotary evaporator, dissolve the residue in 5 mL of ethanol.

Slowly evaporate the ethanol solvent to recrystallize the product in a 10-mL beaker. Obtain the product (11.5 g) as yellowish powder and the yield of product is 90% based on bromoacetophenone. From the 1H NMR analysis, 1H NMR (DMSO): δ 3.78 (s, 3H, OCH3), 5.54 (s, 2H, CH2), 6.82-8.01 (m, 9H, aromatic) ppm.17

7. Hydrodeoxygenation of Lignin-derived Aromatic Ether

NOTE: The chosen lignin-derived aromatic ether is anisole in this experiment and the catalyst is Ni0.92Nb0.08O. Use appropriate protective equipment and fume hood to perform the reaction using carcinogenic reagents.

Equip a 50-mL stainless steel autoclave reactor with a heater and a magnetic stirrer.

Reduce the Ni0.92Nb0.08O catalyst (1 g) obtained from step 2 in the autoclave reactor in H2 atmosphere at 400 °C for 2 h, and then passivate the catalyst under Argon (50 mL/min) overnight.

Dissolve anisole (1.1712 g, 8 wt%) into n-decane (20 mL) with the use of n-dodecane (0.2928 g, 2 wt%) as an internal standard for quantitative gas chromatography (GC) analysis.

Introduce the reduced catalysts (0.1 g) in into the autoclave reactor rapidly to avoid long exposure time with air (< 5 mins).

Seal the autoclave reactor, purge with H2 repeatedly (3 times, at 3 MPa pressure) to eliminate air, and then the reaction mixture at atmosphere pressure.

Set the stirring speed at 700 rpm.

After heating to the desired temperature at 160-210 °C at 2 °C/min, pressurize the autoclave reactor to 3 MPa and set the zero-time point (t = 0). NOTE: The temperature range of 160-210 °C is appropriate in this report.

Subsequently, cool the mixture to room temperature at 10 °C/min immediately and analyze the deoxygenated products using gas chromatography with mass selective detector.17

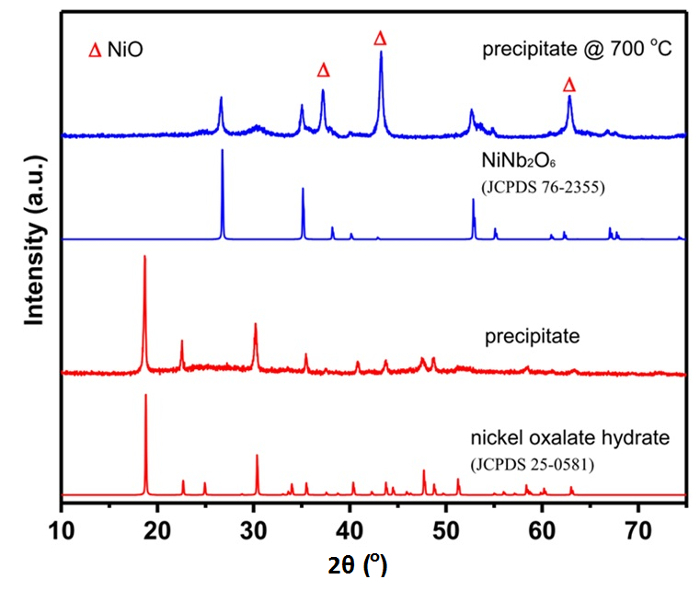

Determine the conversion of lignin model compound according to the following equation:

Determine the product selectivity according to the following equation:

Representative Results

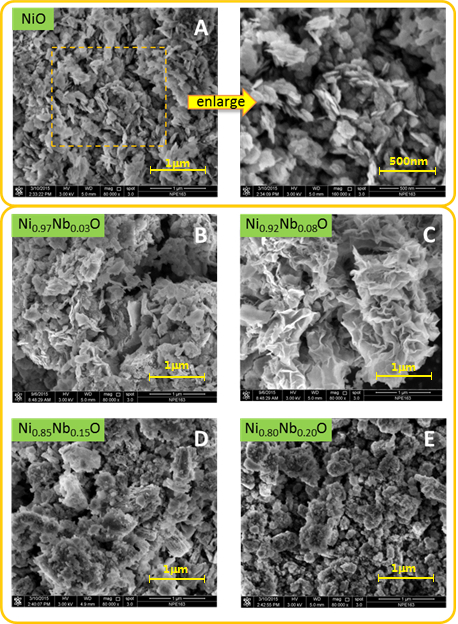

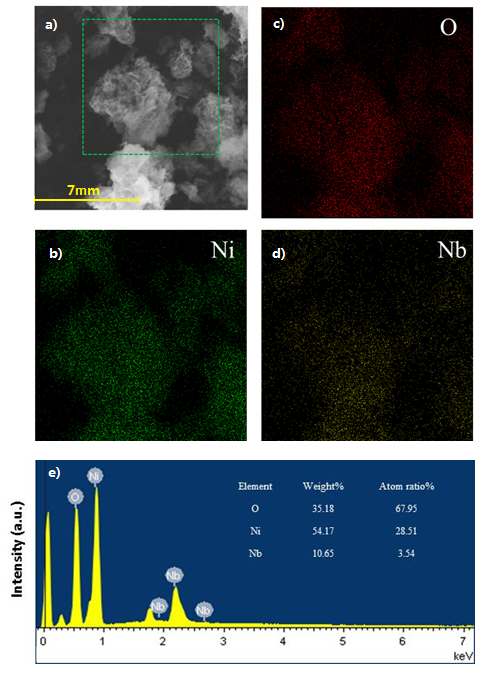

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns (Figure 1 and Figure 2), BET surface areas, temperature-programmed reduction of hydrogen with hydrogen (H2-TPR), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) analyzer, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) were collected for the nanoparticles NiO, Ni-Nb-O and Nb2O5 oxides17 (Figure 3 and Figure 4). XRD, SEM and XPS are used to determine the phase and morphology of the nanostructures. The physicochemical properties of Ni-Nb-O mixed oxides were collected in Table 1.17

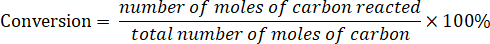

The structure of the catalysts has been previously reported and discussed.17 The X-ray diffraction pattern collected for the mixed-oxide formed by chemical precipitation of nickel nitrate and hydrated niobium (V) oxalate (Figure 1), is in good agreement with that observed for hydrated nickel oxalate (JCPDS 25-0581). After calcination with mixed-oxide precipitates for 2 h at 700 °C, the peaks observed at 2θ of 26.8°, 35.2° and 52.9° (JCPDS 76-2355) are corresponding to crystalline NiNb2O6 phase.

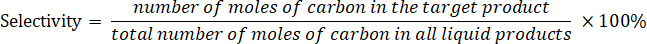

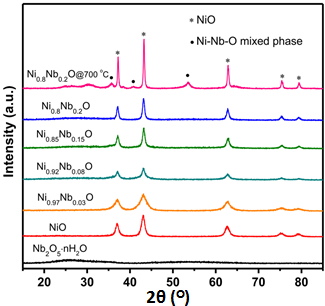

The X-ray diffraction pattern collected for the synthesized NixNb1-xO nanoparticle after calcination for 5 h at 450 °C (Figure 2), display main diffraction peaks located at 2θ of 37.1°, 43.2°, 62.5°, 74.8° and 78.7°, correspond to the (111), (200), (220), (311) and (222) reflections, respectively. This is in a good agreement of the crystalline NiO bunsenite structure (JCPDS 89-7130). Besides, it is clearly noted that a low intensity broad background peak appears at about 26° with increases in Nb loading, which is attributed to the emergence of the amorphous niobium oxides as a result of the chemical precipitation possessing of Nb5+ and hydroxyl ion18. Upon calcination at 700 °C, the peaks corresponding to Ni-Nb-O mixed phase are observed in the X-ray diffraction pattern of Ni0.8Nb0.2O, which indicate that the existence of amorphous after calcination at 450 °C,19 but not the crystalline Ni-Nb composite phase. It was documented that high % of Nb could lead to the formation of mixed phase Ni-Nb-O, e.g. NiNb2O6, Ni3Nb2O8 and Ni4Nb2O9, which would decrease the catalytic capability.

Scanning electron microscopy analysis show the dramatically different surface morphology of the NixNb1-xO nanoparticles from NiO (Figure 3). In contrast to the well-defined nanosheet crystalline structures of the Pure NiO, fold-like and sponge-like appearance are clearly observed on the sheet-like NiO surface with small void spaces for Ni0.97Nb0.03O and Ni0.92Nb0.08O, respectively.9 The sponge-like species are identified as the Ni-Nb solid solution due to the incorporation of the Nb in the NiO lattice structure, as a result of the comparable ionic radius of Ni2+ (0.69 Å) and Nb5+ (0.64 Å) cations.9,20 As a result, sponge-/block-like appearance and round crystallites with fewer number of small void spaces are observed for the Ni0.85Nb0.15O and Ni0.8Nb0.2O nanoparticles due to the increased Nb content in the sample. In addition, the energy-dispersive X-ray maps show that the niobium oxide are well-dispersed over the bulk NiO sample (Figure 4). Its niobium-enriched surface is further confirmed by the larger surface Nb:Ni ratio of Ni0.92Nb0.08O sample (0.11/0.92), compared with bulk theoretical value (0.08/0.92). This can be explained by the fact that the surface of the as-prepared Ni-Nb-O is enriched with Ni nanoparticles.

The catalytic performance of this as-prepared Ni-Nb-O metal oxide was tested with the hydrodeoxygenation of anisole as the model reaction. The reaction was performed in an autoclave reactor at 3 MPa and at 160 °C. 0.1 g of Ni0.92Nb0.08O catalyst was placed in a mixture of 8 wt % anisole and 20 mL n-decane. After 2 h, 95.3 % conversion was obtained with 31.8 % selectivity from anisole to cyclohexane. After 12 h, the anisole was completely converted to pure cyclohexane. Instead of extending the reaction time, the effect of temperature on the catalytic performance was also investigated. Within 2 h, anisole was completely converted to cyclohexane if the temperature was set at 200 °C instead of 160 °C. Current effort has been focused on the conversion of other lignin-derived model compound with higher molecular weight to investigate the hydrodeoxygenation ability of such catalyst.

Figure 1. XRD patterns of precipitate formed by mixing nickel nitrate and niobium (V) oxalate hydrate in water at 70 °C and after calcination at 700 °C. JCPDS is Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards Database. JCPDS 76-2355 is the Standard XRD reference patterns for NiNb2O6 materials. JPCDS 25-0581 is the Standard XRD reference patterns for nickel oxalate hydrate materials. This figure has been modified from Shaohua Jin et al.17 Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2. XRD patterns of Ni-Nb-O mixed oxide catalysts after calcination at 450 °C in air for 5 h. This figure has been modified from Shaohua Jin et al.17Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3. Scanning electron microscopy micrographs of NiO and Ni-Nb-O mixed oxides. This figure has been modified from Shaohua Jin et al.17Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4. Scanning Electron Micrograph, X-ray maps and Energy Dispersive X-ray analysis of Scanning Electron Micrograph.a) Scanning Electron Micrograph of Ni0.92Nb0.08O. b) X-ray maps of Ni. c) X-ray maps of O. d) X-ray maps of Nb. e) Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDX) results of Ni0.92Nb0.08O sample. This figure has been modified from Shaohua Jin et al.17 Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

| Catalysts | Nb/Ni ratio | SBET (m2/g) | d (nm) | Vtotal (cm3/g) | Crystallite size (nm)a |

| NiO | 0 | 136 | 18 | 0.61 | 9.3 |

| Ni0.97Nb0.03O | 0.031 | 158 | 16.5 | 0.65 | 8 |

| Ni0.92Nb0.08O | 0.087 | 173 | 9.6 | 0.41 | 5.4 |

| Ni0.85Nb0.15O | 0.176 | 139 | 12.5 | 0.43 | 11.8 |

| Ni0.80Nb0.20O | 0.25 | 110 | 12 | 0.33 | 14.5 |

| Nb2O5·nH2O | - | 122 | 6.7 | 0.2 | - |

| a Determined by considering the NiO (200) peak higher intensity. |

Table 1. Physicochemical properties of NiO, Nb2O5 and Ni-Nb-O mixed oxides. This table has been modified from Shaohua Jin et al.17

Discussion

One of the common methods to prepare the nickel-doped bulk niobium oxide nanoparticles is rotary evaporation method.9 By employing various pressure and temperature conditions during the process of rotary evaporation, the precipitation of Ni-Nb-O particles commerce with the slow removal of the solvent. In contrast to the rotary evaporation method, the chemical precipitation method reported in this study has received increasing attention to prepare the nanoparticles as this do not require the removal of solvents. In the typical chemical precipitation methods to prepare the nanocatalysts, alkaline solution is necessary to be added dropwise into the solution of metal salts over a long period of time.21 In our study, a mixture of ammonia hydroxide and sodium hydroxide solution was used as the precipitating agents. One of the critical steps in chemical precipitation method is the speed of the addition of the precipitating agent.22,23 Care must be taken in controlling the speed of the addition of the precipitating agents, i.e., the basic mixtures, and it is best controlled at a rate of one drop per second. If possible, peristaltic pump can be used to precisely control the addition of the precipitating agents.

Apart from the addition rate, the control of temperature is another important key for successful precipitation as the morphology of the as-prepared metal oxides are highly dependent on the temperature used in the preparation. Though it is not clear in the correlation between the morphology of nanoparticles and their related catalytic performance, the optimization of the preparation temperature to develop the efficient nanocatalysts is essential.

As Brønsted and Lewis acid sites are necessary for HDO process to convert phenolic and oxygen-containing aromatics to hydrocarbons,17 the optimization of the acid site's amount is also critical factor to improve the catalytic properties of nanoparticles. According to the related mechanistic study in the chemical precipitation methods of nanoparticles, the amount of the Brønsted sites are highly dependent on the amount of remaining water on the catalysis.24 Thus, controlling the drying periods and the calcination temperature of catalysts are also critical steps in the protocol in order to optimize the catalytic properties of the catalysts.

Compared with other common nanoparticle preparation methods, chemical precipitation method has received increasing attention to prepare the nanoparticles. It is probably because this do not require the removal of solvents in the preparation. In addition, this method is capable to promote the uniform dispersion of metal components and commonly used in the preparation of nanoparticles with relatively larger surface areas.17 However, this method is preferable to prepare metal oxide catalyst with relatively higher concentration of metal ions such as those of transition metal elements.25,26,27 Thus, it is not recommended to prepare alkaline earth metal oxide using this method.

The suspension is then treated by a mixture of sodium hydroxide and ammonium hydroxide aqueous solution at pH 9 to allow the complete precipitation of residual Ni2+ and Nb5+ cations in the sample, followed by washing with deionized water repeatedly to remove excess Na+ cation. After subsequent calcination in synthetic air at 450 °C, the NixNb1-xO nanoparticles are prepared and analyzed.

Surface areas, pore volume and size collected for the synthesized NixNb1-xO (Table 1) indicate that the chemical precipitation synthesis by incorporating appropriate proportion of Nb into the NiO (Nb:Ni ratio < 0.087) could effectively increase the surface areas of the materials, since niobium oxalate is used as the precursor. This is also supported by the fact that more porous structure can be formed by the chemical decomposition of hydrated nickel oxalate with organic nature,9 as observed in the X-ray diffraction pattern (Figure 1). However, the surface area of NixNb1-xO decreases significantly when the Nb:Ni ratio is raised to 0.15 and 0.25. This is probably due to the formation of large block-like crystallites in the sample. Scherrer formula is used to calculate the crystallite size of all prepared mixed-oxide. It can be concluded that the size of the crystallite is closely related to the corresponding surface area. We demonstrated elsewhere that the Nb:Ni ratio is a crucial factor in determining the catalytic activity of the oxides towards the hydrodeoxygenation of lignin-derived organic compounds. With high Nb % (Nb:Ni > 0.087), inactive NiNb2O6 species were formed by the reaction between the amorphous phase of Nb and NiO, leading to the aggregation of NiO and thus catalyst with lower surface area was obtained. With lower Nb % (Nb:Ni ≤ 0.087), the addition of niobium oxalate can increase the surface area of the catalyst. This is attributed by the fact that the as-formed Ni oxalate retard the crystal growth of the NiO crystallites, as a result catalyst with higher specific area was obtained. On the other hand, for catalyst with lower amount of Nb, the amorphous Nb2O5 can promote the dispersion of NiO crystallites on the surface, thus aggregation of NiO crystallites was inhibited. The large surface area (173 m2/g) of Ni0.92Nb0.08O, consisting of fold-like nanosheets, showed the best activity and selectivity towards the hydrodeoxygenation of anisole to cyclohexane.

In summary, we demonstrate a chemical precipitation method to prepare the Ni-Nb-O oxide catalysts. Though this method requires relatively higher concentration of metal ions solution, it has been found to successfully prepare the nanocatalysts with higher surface areas, compared those obtained from other methods. Besides, the newly prepared nanoparticles showed excellent catalytic activity in the hydrodeoxygenation of anisole to cyclohexane. The study of their applications in other catalytic systems such as hydrogenation is currently in progress. In addition, it is anticipated that a similar strategy could be further applied in the preparation of other different mixed Ni-Me-O oxides or other nanomaterials such as those with Cu2+, Co2+ with high specific surface area for various useful applications such as oxidation of alcohol and water and catalytic coupling reactions.28,29,30

Disclosures

We have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by National Key Research & Development Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2016YFB0600305), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21573031 and 21373038), Program for Excellent Talents in Dalian City (2016RD09) and Technological and Higher Education Institute of Hong Kong (THEi SG1617105 and THEi SG1617127).

References

- Zhou Y, Yang M, Sun K, Tang Z, Kotov NA. Similar topological origin of chiral centers in organic and nanoscale inorganic structures: effect of stabilizer chirality on optical isomerism and growth of CdTe nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132(17):6006–6013. doi: 10.1021/ja906894r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, et al. Optical Coupling Between Chiral Biomolecules and Semiconductor Nanoparticles: Size-Dependent Circular Dichroism Absorption. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:11456–11459. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, et al. Reversible plasmonic circular dichroism of Au nanorod and DNA assemblies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134(7):3322–3325. doi: 10.1021/ja209981n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, et al. Manipulation of collective optical activity in one-dimensional plasmonic assembly. ACS Nano. 2012;6(3):2326–2332. doi: 10.1021/nn2044802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, et al. Gold nanorod@chiral mesoporous silica core-shell nanoparticles with unique optical properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135(26):9659–9664. doi: 10.1021/ja312327m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Zhu Z, Li Z, Zhang W, Tang Z. Conformation Modulated Optical Activity Enhancement in Chiral Cysteine and Au Nanorod Assemblies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:16104–16107. doi: 10.1021/ja506790w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao CNR, Gopalakrishnan J. New Directions in Solid State Chemistry. Cambridge University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Rosenfeld DC, Anjum DH, Caps V, Basset J-M. Green Synthesis of Ni-Nb Oxide Catalysts for Low-Temperature Oxidative Dehydrogenation of Ethane. ChemSusChem. 2015;8:1254–1263. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201403181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heracleous E, Lemonidou AA. Ni-Nb-O Mixed Oxides as Highly Active and Selective Catalysts for Ethene Production via Ethane Oxidative Dehydrogenation. Part I: Characterization and Catalytic Performance. J. Cat. 2006;237:162–174. [Google Scholar]

- Savova B, Loridant S, Filkova D, Millet JMM. Ni-Nb-O Catalysts for Ethane Oxidative Dehygenation. Appl. Catal. A. 2010;390(1-2):148–157. [Google Scholar]

- Heracleous E, Delimitis A, Nalbandian L, Lemonidou AA. HRTEM Characterization of the Nanostructural Features formed in Highly Active Ni-Nb-O Catalysts for Ethane ODH. Appl. Catal. A. 2007;325(2):220–226. [Google Scholar]

- Skoufa Z, Heracleous E, Lemonidou AA. Unraveling the Contribution of Structural Phases in Ni-Nb-O mixed oxides in Ethane Oxidative Dehydrogenation. Catal. Today. 2012;192(1):169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Heracleous E, Lemonidou AA. Ni-Me-O Mixed Metal Oxides for the Effective Oxidative Dehydrogenation of Ethane to Ethylene - Effect of Promoting Metal Me. J. Cat. 2010;270:67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, et al. Nb Effect in the Nickel Oxide-Catalyzed Low-Temperature Oxidative Dehydrogenation of Ethane. J. Cat. 2012;285:292–303. [Google Scholar]

- Sadovskaya EM, et al. Mixed Spinel-type Ni-Co-Mn Oxides: Synthesis, Structure and Catalytic Properties. Catal. Sustain. Energy. 2016;3:25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez J, et al. Ni-Nb-Based Mixed Oxides Precursors for the Dry Reforming of Methane. Top. Catal. 2011;54:170–178. [Google Scholar]

- Jin S, Guan W, Tsang C-W, Yan DYS, Chan C-Y, Liang C. Enhanced hydroconversion of lignin-derived oxygen-containing compounds over bulk nickel catalysts though Nb2O5 modification. Catal. Lett. 2017;147:2215–2224. [Google Scholar]

- Taghavinezhad P, Haghighi M, Alizadeh R. CO2/O2-oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane to ethylene over highly dispersed vanadium oxide on MgO-promoted sulfated-zirconia nanocatalyst: Effect of sulfation on catalytic properties and performance. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2017;34(5):1346–1357. [Google Scholar]

- Muralidharan G, Subramanian L, Nallamuthu SK, Santhanam V, Kumar S. Effect of Reagent Addition Rate and Temperature on Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles in Microemulsion Route. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011;50(14):8786–8791. [Google Scholar]

- Sosa YD, Rabelero M, Treviño ME, Saade H, López RG. High-Yield Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles by Precipitation in a High-Aqueous Phase Content Reverse Microemulsion. J. Nanomater. 2010. pp. 1–6.

- Morterra C, Cerrato G, Pinna F. Infrared spectroscopic study of surface species and of CO adsorption: a probe for the surface characterization of sulfated zirconia catalysts. Spectrochim. Acta. A Molecul. Biomolecul. Spectrosc. 1998;55:95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Wang Q, Yan J, Fang J, Zhao J, Shen W. Preparation of High Pore Volume Pseudoboehmite Doped with Transition Metal Ions through Direct Precipitation Method. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012;51(47):15386–15392. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh R, Djaja NF. Transition-metal-doped ZnO nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic activity under UV light. Spectrochim. Acta. A Molecul. Biomolecul. Spectrosc. 2014;130:581–590. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2014.03.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertis IF, Boz I. Synthesis and Characterization of Metal-Doped (Ni, Co, Ce, Sb) CdS Catalysts and Their Use in Methylene Blue Degradation under Visible Light Irradiation. Modern Research in Catalysis. 2017;6:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jin S, et al. Cleavage of Lignin-Derived 4-O-5 Aryl Ethers over Nickel Nanoparticles Supported on Niobic Acid-Activated Carbon Composites. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015;54(8):2302–2310. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas E, Delgado JJ, Guerrero-Pérez MO, Bañares MA. Performance of NiO and Ni-Nb- O Active Phases during the Ethane Ammoxidation into Acetonitrile. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013;3(12):3173–3182. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S-H, et al. Raman Spectroscopic Studies of Ni-W Oxide Thin Films. Solid State Ionics. 2001;140(1):135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Mondal A, Mukherjee D, Adhikary B, Ahmed MA. Cobalt nanoparticles as recyclable catalyst for aerobic oxidation of alcohols in liquid phase. J. Nanopart. Res. 2016;18(5):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Yang L, Zhao W, Cao L, Sun Z, Zhang F. A facile synthesis of copper nanoparticles supported on an ordered mesoporous polymer as an efficient and stable catalyst for solvent-free sonogashira coupling Reactions. Green Chem. 2017;19:1949–1957. [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, et al. High-Selectivity Electrochemical Conversion of CO2 to Ethanol using a Copper Nanoparticle/N-Doped Graphene Electrode. Chemistry Select. 2016;1:6055–6061. [Google Scholar]