Abstract

Objectives

The MBL2 gene is the major genetic determinant of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) – an acute phase reactant. Low MBL levels have been associated with adverse outcomes in preterm infants. The MBL2Gly54Asp missense variant causes autosomal dominant MBL deficiency. We tested the hypothesis that MBL2Gly54Asp is associated with worse neurodevelopmental outcomes after cardiac surgery in neonates.

Methods

This is an analysis of a previously described cohort of non-syndromic congenital heart disease (CHD) patients who underwent cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass before 6 months of age (n=295). Four-year neurodevelopment was assessed in three domains: Full-Scale Intellectual Quotient (FSIQ), the Visual Motor Integration (VMI) development test, and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) to assess behavioral problems. The CBCL measured total behavioral problems, pervasive developmental problems (PDPs), and internalizing/externalizing problems. A multivariable linear regression model, adjusting for confounders, was fit.

Results

MBL2Gly54Asp was associated with a significantly increased covariate-adjusted PDP score (β=3.98, P=0.0025). Sensitivity analyses of the interaction between age at first surgery and MBL genotype suggested effect modification for the patients with MBL2Gly54Asp (Pinteraction=0.039), with the poorest neurodevelopment outcomes occurring in children who had surgery earlier in life.

Conclusions

We report the novel finding that carriers of MBL2Gly54Asp causing autosomal dominant MBL deficiency have increased childhood pervasive developmental problems after cardiac surgery, independent of other covariates. Sensitivity analyses suggest that this effect may be larger in children who had surgery at earlier ages. These data support the role of non-syndromic genetic variation in determining post-surgical neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with CHD.

INTRODUCTION

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common human birth defect, frequently requiring surgical intervention with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) or circulatory arrest soon after birth. Although survival has improved, studies have identified a higher incidence of adverse neurological and functional outcomes in survivors of neonatal surgery for CHD1,2. Neurodevelopmental dysfunction is the most common adverse post-surgical outcome, with approximately 15% and 30% of survivors showing symptoms of pervasive developmental problems (PDPs) and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), respectively, by 5 years of age3.

Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) is a hepatic-derived acute phase reactant that activates the complement system4. Serum levels of MBL in humans are entirely determined by the MBL2 gene (MBL1 is a non-functional pseudo-gene)5. Prior work identified a Glycine-to-Aspartate missense variation at the 54th codon of the MBL2 protein (MBL2Gly54Asp, rs1800450, population minor allele frequency (MAF) of approximately 14%) as the cause of autosomal dominant MBL deficiency (Mendelian Inheritance in Man (MIM) number: 614372); these patients manifest recurrent neonatal infections6,7. A single copy of MBL2Gly54Asp decreases serum MBL activity by approximately 90% - to the level of those with two copies of MBL2Gly54Asp6,7, likely through a dominant-negative effect, whereby proteins with the Aspartate protein change interfere with oligomerization of MBL into the mature, polymerized serum molecule that is then involved in carbohydrate recognition and initiation of the complement cascade8. In addition, a single copy of MBL2Gly54Asp has been associated with increased prevalence of sepsis in neonates9 and adverse neurological outcomes in preterm infants10.

Given the importance of MBL in immunity for neonates and its potential link to adverse neurological events, we hypothesize that MBL2Gly54Asp also affects neurodevelopment. Thus, in this study we sought to determine whether autosomal dominant MBL deficiency, as caused by MBL2Gly54Asp, is associated with differential neurodevelopmental outcomes at 4-year follow-up in children with isolated CHD who required surgical palliation.

METHODS

Ethics Statement

Participants were enrolled at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) on a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Boards of CHOP and the University of Washington (analysis) from 10/1998 – 04/2003. Informed, written consent was obtained from parents or guardians of all the participants.

Patient Population

This is an analysis of a previously described prospective cohort of 550 participants enrolled in a prospective study at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia to study neurodevelopmental dysfunction after surgical correction for CHD11–14. Patients 6 months of age or younger who underwent CPB with or without deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (DHCA) for repair of CHD were eligible for enrollment. Exclusion criteria included (1) multiple distinct congenital anomalies, (2) a likely genetic or phenotypic syndrome, and (3) a language other than English spoken in the home. This study examined a subset of the cohort with both genetic and 4-year neurodevelopmental outcome data (n=295).

Of the original 550 CHD cases, 381 returned for four-year neurodevelopmental assessment. An additional 53 participants were excluded due to presence of chromosomal/genetic abnormalities (e.g., DiGeorge/22q11.2 deletion syndrome), which would be expected to bias the results due to high prevalence of poor neurodevelopmental outcomes as compared to non-syndromic CHD patients3,15. Thirty-three (33) patients were excluded due to a lack of high quality genotype data. There were 295 patients considered after these exclusions. Information on data collection (including further information on inclusion/exclusion criteria) operative management, and genotyping have been previously reported in detail12.

Genetic Evaluation to Exclude Syndromic CHD Participants

CHD participants were evaluated by a genetic dysmorphologist and genetic counselor at the 1-year and/or 4-year examinations. Patients were classified as either: having no indication of genetic syndrome or chromosomal abnormality (normal, isolated CHD), suspected genetic syndrome (suspect), or a definite genetic syndrome or chromosomal abnormality (genetic). Following this classification, genetics records for each patient with a CHD were individually reviewed by a second senior board-certified medical geneticist, blinded to the genetic data, to determine whether participants were to be included or excluded from the current analysis, which focuses on non-syndromic participants. Due to this review, 53 CHD participants with known or suspected genetic syndromes were excluded from analysis due to the potential for genetic confounding effects on neurodevelopmental outcomes3,15.

Four-Year Neurodevelopmental Examinations

Neurodevelopmental evaluations were performed between the fourth and fifth birthdays. Growth measurements (weight, length, and head circumference) were recorded and a health history was obtained, focusing on the incidence of interim illnesses, hospitalizations, neurologic events or interim evaluations, current medication use, and parental concerns about health. Parents were asked specifically whether they had ever been told that their child had autism, Asperger syndrome, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified, or ADHD.

General child intelligence and visual-motor input integration were tested using the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence – Third Edition16 and the Beery-Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration – Sixth Edition17, respectively. Both the full-scale intelligence quotient (FSIQ) and visual-motor integration (VMI) score are standardized to a mean of 100, with a standard deviation of 15.

Behavioral skills were assessed through parental report by using the Child Behavior Checklist for ages 1.5 to 5 years (CBCL/1.5-5)18. The CBCL/1.5-5 is a questionnaire used to obtain parental reports of behavior problems demonstrated within the previous 6 months. The pervasive developmental problems (PDP) score is one of the clinically-oriented scores resulting from the CBCL/1.5-5 and has been previously utilized to identify preschoolers at risk for autism19. Other scores from the CBCL/1.5-5 include a total problem score and two broad behavioral indices (internalizing and externalizing problems). The CBCL/1.5-5 total problems score consists of the sum of the scores for the 99 specific problem items on the form plus the highest scores for any written-in responses to item 100. The internalizing problems scores summarize specific scores regarding the behaviors of: excessive emotional reactivity, anxious/depressed behavior, somatic complaints, and withdrawn behavior. The externalizing problems score summarizes the two specific behavioral scores of attention problems and aggressive behavior. All raw scores (PDP, total problems, externalizing problems, and internalizing problems) were transformed to T-scores with mean=50 and these T-scores were directly used in analyses.

MBL2Gly54Asp (rs1800450) genotyping

Whole blood or buccal swab samples were obtained before surgery and were stored at 4°C. Genomic DNA was isolated from white blood cells and genotyping was performed using the Illumina HumanHap550-Quad+ BeadChip at the Center for Applied Genomics of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Patient genotypes at rs1800450, the DNA missense variant responsible for autosomal dominant MBL deficiency, were extracted from the larger, non-imputed genetic dataset using PLINK20.

APOE genotyping

Genomic DNA was prepared and was used for determination of APOE genotypes as previously described11. APOE genotypes were classified into three groups as follows: ε2 (ε2ε2, ε2ε3, or ε2ε4) ε3 (ε3ε3), or ε4 (ε4ε3 or ε4ε4), and the APOE ε2 genotype was included as a covariate in the linear regression model for all phenotypes based on considerable prior published evidence that the APOE ε2 genotype is associated with markedly detrimental neurodevelopmental outcomes3,11,21.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses and graphics were performed in R (http://www.r-project.org/) using standard regression packages.

Genetic ancestry was determined using previously described methods22. Due to the mixed ancestry of the cohort, the first three principal component eigenvectors were used as covariates in the linear regression models for neurodevelopmental outcomes to adjust for potential population stratification23.

Due to the autosomal dominant inheritance of MBL deficiency, we categorized patients with one or more copies of the MBL2Gly54Asp missense variant into a single group (hereby termed “MBL deficient genotype”). The distribution of rs1800450 genotype among the cohort was 199 homozygous major, 84 heterozygous, and 12 homozygous minor (96 total MBL deficient genotype patients).

Linear regression models were separately fit for the 6 considered neurodevelopmental outcomes (FSIQ, VMI score, and CBCL PDPs, total score, internalizing problems, and externalizing problems) to assess the association of MBL deficient genotype with each outcome. A Bonferroni-adjusted threshold for significance was set at α=0.0083 to adjust for the 6 total neurodevelopmental outcomes tested (0.05/6). Each linear regression model was adjusted for the previously reported confounding variables: the first three principal component eigenvectors for ancestry, gestational age, birth weight, birth head circumference, diagnostic class (coded as a dummy variable with diagnostic class 1 as the reference group)24, preoperative intubation, preoperative length of stay (LOS), total minutes of cardiopulmonary bypass, total minutes of DHCA, delayed sternal closure, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) use, hematocrit at first surgery, postoperative LOS, mother’s education at 4-year follow-up, and mother’s socioeconomic status at 4-year follow-up. Diagnosis class was assigned based on preoperative diagnosis according to a previously proposed scheme24: class I, two-ventricle heart without arch obstruction; class II, two-ventricle heart with arch obstruction; class III single-ventricle heart without arch obstruction; and class IV, single-ventricle heart with arch obstruction.

Plotting of Gene-by-Environment Interactions

A secondary analysis considering the possibility of effect modification of MBL deficiency by age at first surgery was fit using linear regression. Visualization of this gene-by-environment interaction was obtained through simplification of the linear regression coefficients: [Predicted PDP score = α + β1 (MBL Deficient) + β2 (Age at first surgery) + γ (MBL deficient × Age at first surgery), such that the MBL deficient have coefficients equal to α + β1 + β2 + γ, while those with normal MBL status have coefficients equal to α + β2.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the studied cohort stratified by MBL status are presented in Table 1. A total of 199 patients had normal MBL status, as determined by their homozygous major genotype at rs1800450. An additional 96 participants were classified as having MBL deficient genotype, as they carried one or two copies of the minor allele at rs1800450 (resulting in MBL2Gly54Asp, the missense variant causative for autosomal dominant MBL deficiency (MAF=13%), see MIM:614372). When comparing the two MBL groups and not adjusting for multiple contrasts, the MBL deficient group had significant decreases in preoperative LOS (1.62 vs. 2.37 days, P=0.002) and postoperative LOS (8.85 vs 11.50 days, P=0.011) as well as significant increases in average age at first surgery (57.7 vs. 36.3 days, P=0.013). We also report marginal differences in the distribution of maternal education at 4 years of follow-up (P=0.024) and in self-reported race (P=0.060) between the MBL deficient genotype and normal MBL groups.

Table 1.

Baseline and clinical characteristics of the 295 participants, stratified by MBL status.

| N | Normal MBL (N=199) | MBL Deficient Genotype (N=96) | Two-sided P-value † | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male, % | 295 | 110 (55%) | 56 (58%) | 0.62 |

| Gestational age, weeks | 295 | 38.57 ± 1.87 | 38.45 ± 2.40 | 0.82 |

| Birth weight, kg | 295 | 3.17 ± 0.61 | 3.14 ± 0.71 | 0.52 |

| Birth head circumference, cm | 295 | 33.82 ± 1.49 | 33.85 ± 1.71 | 0.90 |

| Race, % | 295 | |||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 4 (2%) | 3 (3%) | 0.06 | |

| Asian | 7 (4%) | 4 (4%) | ||

| Black | 53 (27%) | 11 (12%) | ||

| Hispanic | 8 (4%) | 5 (5%) | ||

| White | 127 (64%) | 73 (76%) | ||

| APOE ε2 genotype, % | 295 | 21 (10%) | 10 (11%) | 0.99 |

| Diagnostic class, % | 295 | |||

| Class 1 | 97 (49%) | 55 (57%) | 0.59 | |

| Class 2 | 23 (12%) | 9 (9%) | ||

| Class 3 | 21 (11%) | 9 (9%) | ||

| Class 4 | 58 (29%) | 23 (24%) | ||

| Preoperative intubation, % | 295 | 62 (31%) | 24 (25%) | 0.28 |

| Preoperative LOS, days | 295 | 2.37 ± 3.01 | 1.62 ± 2.19 | 0.002 |

| Age at first surgery, days | 295 | 36.3 ± 51.6 | 57.7 ± 59.7 | 0.013 |

| Hematocrit at first surgery, % | 295 | 27.81 ± 3.78 | 27.67 ± 4.53 | 0.94 |

| Total CPB time, min | 295 | 64.5 ± 39.2 | 68.8 ± 37.0 | 0.12 |

| Total DHCA time, min | 295 | 24.4 ± 23.0 | 18.8 ± 22.9 | 0.04 |

| Delayed sternal closure, % | 295 | 21 (11%) | 10 (10%) | 0.97 |

| ECMO use, % | 295 | 5 (3%) | 3 (3%) | 0.76 |

| Postoperative LOS, days | 295 | 11.50 ± 11.08 | 8.85 ± 7.22 | 0.011 |

| Maternal education at 4 years | 295 | |||

| Less than high school | 11 (6%) | 6 (6%) | 0.024 | |

| High school / some college | 93 (46%) | 27 (29%) | ||

| College | 65 (33%) | 44 (45%) | ||

| Graduate | 30 (15%) | 19 (20%) | ||

| Maternal SES quintile at 4 years | 295 | |||

| 1 | 6 (3%) | 4 (4%) | 0.85 | |

| 2 | 17 (9%) | 7 (7%) | ||

| 3 | 38 (19%) | 15 (15%) | ||

| 4 | 64 (33%) | 31 (32%) | ||

| 5 | 71 (36%) | 40 (42%) | ||

| FSIQ score | 292 | 97.8 ± 17.7 | 99.3 ± 17.9 | – |

| VMI score | 294 | 94.9 ± 17.9 | 93.3 ± 16.6 | – |

| CBCL/1.5-5 measures | ||||

| Total problems | 295 | 47.4 ± 10.4 | 48.8 ± 12.9 | – |

| Internalizing problems | 295 | 48.1 ± 10.6 | 50.3 ± 12.9 | – |

| Externalizing problems | 295 | 46.4 ± 10.3 | 46.6 ± 11.8 | – |

| PDPs score | 295 | 54.08 ± 6.60 | 56.28 ± 8.81 | – |

Abbreviations: APOE – apolipoprotein E gene; CBCL/1.5-5 – Child Behavior Checklist 1.5 to 5 years; CPB – cardiopulmonary bypass; DHCA – deep hypothermic circulatory arrest; ε2 – APOE genotype associated with poor neurodevelopmental outcomes (see Methods); ECMO – extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; FSIQ – Full Scale Intellectual Quotient; LOS – length of stay; MBL – mannose-binding lectin; PDPs – pervasive developmental problems; SES – socioeconomic status; VMI – Visual Motor Integration.

Differences in proportions were assessed using the chi-square test. Tests of differences in means were performed using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test.

To determine whether MBL status was associated with four-year neurodevelopmental outcomes, a multivariable linear regression model adjusting for numerous potential confounders (see “Statistical Analysis” subsection of the Methods) was applied. The differences in the other underlying risk factors between genotype groups are thus accounted for when testing the effect of genotype on each neurobehavioral outcome. Of the six tested neurodevelopmental outcomes, no association was noted for MBL deficient genotype and the outcomes of FSIQ (B= −2.78, P=0.31), VMI (B= −2.89, P=0.33), or CBCL/1.5-5 externalizing problems (B=1.40, P=0.46) scores. Nominally significant associations were observed between the MBL deficient genotype group and CBCL/1.5-5 total problems (B=3.23, P=0.097) and internalizing problems (B=3.33, P=0.093) scores. A statistically significant association, after Bonferroni correction for six tests (α=0.0083), was identified between the MBL deficient genotype group and CBCL/1.5-5 PDP score (B=3.98, P=0.0025). These results are summarized in Table 2. Sensitivity analyses stratifying by self-reported race and diagnostic class did not demonstrate differences in the direction of effect for the MBL deficient genotype.

Table 2.

Association of autosomal dominant MBL deficiency genotype with 4-year neurodevelopmental outcomes.

| Outcome* | Beta Coefficient ± SE | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| FSIQ Score† | −2.78 ± 2.75 | 0.31 |

| VMI Score† | −2.89 ± 2.98 | 0.33 |

| CBCL Total Problems Score‡ | 3.23 ± 1.94 | 0.097 |

| CBCL Persistent Developmental Problems Score‡ | 3.98 ± 1.30 | 0.0025 |

| CBCL Internalizing Problems Score‡ | 3.33 ± 1.97 | 0.093 |

| CBCL Externalizing Problems Score‡ | 1.40 ± 1.88 | 0.46 |

Abbreviations: CBCL – Child Behavior Checklist 1.5 to 5 years; FSIQ – Full Scale Intellectual Quotient; VMI – Visual Motor Integration

Linear regression model for association of autosomal dominant MBL deficiency and 4-year neurodevelopmental outcomes adjusts for: first 3 principal component eigenvectors (to adjust for genetic ancestry stratification), gestational age, birth weight, birth head circumference, APOE ε2 genotype, diagnostic class (class 1 as the reference group), preoperative intubation, preoperative length of stay, hematocrit at first surgery, total minutes of deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, total minutes of cardiopulmonary bypass, delayed sternal closure, use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, postoperative length of stay, mother’s education at 4-year follow-up (lowest education group as the reference), mother’s socioeconomic status at 4-year follow-up (lowest socioeconomic quintile as the reference), and age at first surgery.

For FSIQ and VMI scores, scores have a mean of 100, with lower scores and negative beta coefficients corresponding to increased prevalence of problems in neurodevelopment.

For CBCL outcomes, the T-scores have a mean of 50, with higher scores and beta coefficients corresponding to increased prevalence of problems in neurodevelopment.

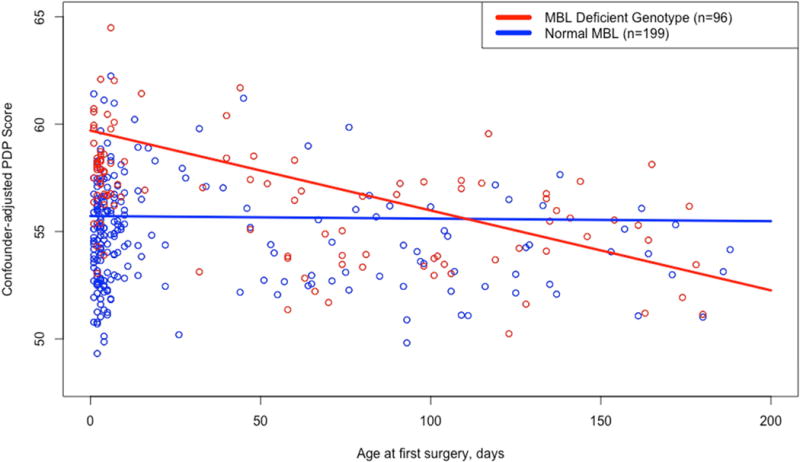

We further sought to identify potential effect modification of the association between the MBL deficient genotype and CBCL/1.5-5 PDP score by performing sensitivity analyses including an interaction term between MBL deficient genotype with (separately) preoperative LOS, age at first surgery, total DHCA time, and postoperative LOS, all of which differed by MBL status (see Table 1). Of these, no interaction was noted between MBL deficient genotype and preoperative LOS, total DHCA time, or postoperative LOS. However, an association was observed between age at first surgery and MBL deficient genotype (γinteraction= −0.036, Pinteraction=0.039, see Table 3). Plotting of this gene-by-environment interaction demonstrated a more deleterious neurodevelopmental effect (higher PDP scores) for neonates with the MBL deficient genotype who underwent surgery at an early age (see Figure 1). Patients who had surgery before 30 days of age and were MBL deficient had a mean covariate-adjusted PDP score of 58, as compared to 55 for the normal MBL group. In comparison, among patients who had surgery after 90 days of age, both MBL deficient and normal groups had a mean PDP score of 55.

Table 3.

Full multivariable linear regression model coefficients for the outcome of pervasive developmental problems, including an interaction term between MBL deficiency and age at first surgery.

| Variable | Beta Coefficient ± SE | %Variation | P - Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 55.72 ± 12.81 | – | – |

| Male, % | −1.04 ± 0.89 | 0.23 | 0.24 |

| Gestational age, weeks | −0.25 ± 0.26 | 0.47 | 0.33 |

| Birth weight, kg | −0.0019 ± 0.0074 | 0.020 | 0.80 |

| Birth head circumference, cm | 0.15 ± 0.30 | 0.060 | 0.63 |

| PC1 | −12.25 ± 11.29 | – | – |

| PC2 | 12.52 ± 10.07 | – | – |

| PC3 | −6.26 ± 10.84 | – | – |

| APOE ε2 genotype, % | 3.49 ± 1.33 | 2.27 | 0.0089 |

| Diagnostic class, % | |||

| Diagnostic class 2 | −0.62 ± 1.44 | 0.20 | 0.67 |

| Diagnostic class 3 | 1.80 ± 1.86 | 0.070 | 0.33 |

| Diagnostic class 4 | 2.49 ± 1.98 | 0.64 | 0.21 |

| Preoperative intubation, % | 0.79 ± 1.01 | 0.096 | 0.43 |

| Preoperative LOS, days | 0.11 ± 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.50 |

| Hematocrit at first surgery, % | −0.23 ± 0.11 | 1.02 | 0.043 |

| Total DHCA time, min | 0.022 ± 0.038 | 0.049 | 0.56 |

| Total CPB time, min | 0.0038 ± 0.018 | 0.039 | 0.83 |

| Delayed sternal closure, % | 0.93 ± 1.53 | 0.16 | 0.55 |

| ECMO use, % | 2.74 ± 3.02 | 0.079 | 0.37 |

| Postoperative LOS, days | 0.12 ± 0.055 | 1.33 | 0.024 |

| Maternal education at 4 years | |||

| High school / some college | −3.39 ± 2.00 | 0.47 | 0.090 |

| College | −3.55 ± 2.14 | 0.20 | 0.098 |

| Graduate | −4.35 ± 2.27 | 0.60 | 0.057 |

| Maternal SES quintile at 4 years | |||

| 2 | 2.81 ± 2.76 | 0.13 | 0.31 |

| 3 | 1.89 ± 2.56 | 0.29 | 0.46 |

| 4 | 0.91 ± 2.61 | 0.081 | 0.73 |

| 5 | 1.87 ± 2.67 | 0.23 | 0.48 |

| Age at first surgery, days | −0.0012 ± 0.011 | 0.11 | 0.62 |

| MBL deficiency, % | 3.98 ± 1.30 | 2.05 | 0.0079 |

| MBL deficiency × Age at first surgery interaction | −0.036 ± 0.017 | 0.53 | 0.039 |

Abbreviations: APOE – apolipoprotein E gene; CBCL/1.5-5 – Child Behavior Checklist 1.5 to 5 years; CPB – cardiopulmonary bypass; DHCA – deep hypothermic circulatory arrest; ECMO – extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; FSIQ – Full Scale Intellectual Quotient; LOS – length of stay; MBL – mannose-binding lectin; PC – principal component (eigenvectors to adjust for differing genetic ancestry); PDPs – pervasive developmental problems; SES – socioeconomic status; VMI – Visual Motor Integration.

Figure 1. Effect of MBL deficient genotype is modified by age at first surgery, with infants receiving surgery at an early age having significantly higher pervasive developmental problems scores (Pinteraction=0.039).

Predicted values of CBCL/1.5-5 PDP score are 59.7 – 0.0372 × (Age at first surgery, in days) for the MBL deficient genotype group and 55.72 – 0.0012 × (Age at first surgery, in days) for the normal MBL group.

To examine whether the interaction between age at first surgery and MBL deficient genotype reflected differences in CHD severity, we performed a sensitivity analysis for the outcome of PDP score, stratified by CHD diagnostic class24 (see Supplemental Table 1). Patients with CHD class 1 or 2 did not have significant associations for either MBL deficient genotype or age at first surgery (P>0.05). However, patients with CHD class 3 or 4 did have nominally significant associations between MBL deficiency and PDP scores (P=0.044 and P=0.023, respectively). Moreover, the interaction between MBL deficient genotype and age at first surgery trended toward significance in both the class 3 (Pint=0.087) and 4 (Pint=0.057) groups. We also note that children in diagnostic class 3 and 4 tended to have an earlier age at first surgery (Supplemental Figure 1). Thus, although underpowered, we assessed a linear regression model on the outcome of PDP score using a three variable interaction term between CHD diagnostic class, age at first surgery, and MBL deficient genotype (Pint=0.11). We also note that CHD diagnostic class did not separately modify the association of MBL deficient genotype (Pint=0.37) or age at first surgery (Pint=0.19) with the outcome of PDP scores.

To determine whether MBL deficient genotype had an effect on long-term survival we performed an analysis on 422 previously described13,14 non-syndromic CHD patients (see Supplemental Table 2). From these analyses we conclude that MBL deficient genotype is not associated with differential long-term survival (Hazard ratio (HR)=0.81, 95% confidence interval (CI)=0.38–1.71, P=0.58).

DISCUSSION

We report the novel finding of a deleterious neurodevelopmental effect in CHD surgery survivors, with carriers of one or more copy of the MBL2Gly54Asp missense variant having significantly higher scores for covariate-adjusted pervasive developmental problems (PDPs) at four-year follow-up (B=3.98, P=0.0025). This association between MBL deficient genotype and pervasive developmental problems appeared more pronounced, with higher PDP scores in participants with both the MBL deficient genotype and an earlier age at first surgery (Pinteraction=0.039). While MBL deficient genotype was not significantly associated with the other tested neurodevelopmental outcomes, the trend in the direction of effect for each association was consistent with a deleterious effect on neurodevelopment for the MBL deficient genotype group. Overall, this novel association provides additional evidence that genetic variants are important modifiers of morbidity and disability after surgery for CHD.

Other investigators have reported a deleterious effect of MBL deficient genotype on neurological outcomes in preterm infants9,10 and that Mbl −/− knockout mice were at increased risk of traumatic brain injury25. However, evidence for a protective effect of MBL loss or insufficiency has also been reported. Orsini et al. demonstrated a potential role of MBL in ischemic-reperfusion injury by illustrating that Mbl −/− knockout mice were protected from focal cerebral ischemia injury as compared to wild type animals26. Similar results were reported by the same group for the outcome of traumatic brain injury in a sample of six adult humans and 11 mice27, and by a separate group in 135 adult stroke patients28. Separately, in adult cardiovascular disease, low MBL levels have been reported to be protective against multiorgan dysfunction29 and postoperative myocardial infarction30 after cardiac surgery.

As compared to adult and animal studies, investigations into the effect of MBL deficient genotype in pediatric populations have more consistently reported deleterious effects. Notably, low MBL levels and MBL deficient genotypes were noted in a higher proportion of premature neonates as compared to term children31. In addition, among premature neonates, those with low MBL levels at baseline had significantly increased risk of adverse neurologic outcomes32. Further, MBL deficient genotype has been associated with increased risk of respiratory distress syndrome33, sepsis9, and adverse neurological outcomes in neonates10. Within this context of pediatric disease, our results of a deleterious neurodevelopmental effect of MBL deficient genotype are consistent with prior literature. We speculate that the potential mechanism through which MBL deficient genotype exerts its adverse neurodevelopmental effects is indirect: through increased infection risk. This mechanism is strengthened through evidence of decreased complement (C3/C4) levels in MBL deficient genotype patients32, and the consistent literature in pediatric populations that suggest an association between low MBL levels and increased rates of childhood infections6,7, sepsis9, and respiratory distress syndrome33. However, we also report from our data a decrease in both preoperative and postoperative length of stay (LOS) for the MBL deficient genotype group, suggesting that, similar to the adult cardiovascular surgery literature29,30, decreased MBL is protective against immediate injury after cardiac surgery. Further research is necessary to clarify and further elucidate the role of MBL in the immediate setting after cardiac surgery, and in the longer-term with regard to neurologic and neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Some limitations of this study should be considered. First, statistical power was limited owing to the size of the study and lack of comparable cohorts. We addressed this by limiting the number of primary tests to six neurodevelopmental outcomes that broadly assessed function and behavior. However, it is possible that other significant associations in untested neurodevelopmental outcomes were overlooked through this approach. Second, we were unable to measure MBL protein levels directly due to a lack of serum in this long-standing cohort. However, as the studied genetic variant (rs1800450 causing the MBL2Gly54Asp missense variant and resulting autosomal dominant MBL deficiency) is expected to reduce MBL levels by 90%6,7, we believe it is a suitable proxy for MBL levels in vivo. Finally, as these analyses were of four-year neurodevelopmental outcomes requiring follow-up, there is the possibility of survivor bias. To identify if our results reflected survival bias and potentially worse neurodevelopmental outcomes in survivors with MBL deficiency, we performed a secondary analysis and determined that MBL deficient genotype was not associated with differential survival.

In addition to the above limitations of our work, we note that our identified effect modification between MBL deficient genotype and age at first surgery on the outcome of PDP score could also be affected by the observation that those who undergo surgery before 30 days tend to be more severe CHD cases34 (see Supplemental Figure 1). As more severe CHD cases also tend to have poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes12, hypothetical survival of these children could have potentially demonstrated a more deleterious interaction between age at first surgery and MBL deficient genotype on neurodevelopment. To assess this possibility, we performed a sensitivity analysis that demonstrated stronger associations for both MBL deficient genotype and the interaction between age at first surgery and MBL deficiency with PDP scores in the class 3 and 4 children, who have one ventricle with (class 4) or without (class 3) aortic arch obstruction. While this sensitivity analysis was suggestive of further effect modification by CHD severity, modeling of two-way (CHD class-by-Age at first surgery or CHD class-by-MBL deficiency) and three-way (CHD class-by-Age at first surgery-by-MBL deficient genotype) were not suggestive of significance (Pint>0.10). Thus, while we conclude that CHD severity did not affect the deleterious association of MBL deficiency with PDP scores, CHD severity remains an important topic for future follow-up work in the study of neurodevelopment after surgical palliation.

In conclusion, we report the novel association of MBL deficient genotype and poor neurodevelopmental outcomes in the setting of CHD. We further identified effect modification by age at first surgery, whereby children who underwent surgery at an early age and had the MBL deficient genotype were at greater risk of deleterious neurodevelopmental outcomes. Given the importance of neurodevelopmental function in CHD survivors, validation of these results could lead to novel preventative and risk assessment strategies to decrease the long-term morbidity of CHD surgery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the children and families for their participation. Genotyping was performed by the Center for Applied Genomics at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the Fannie E. Rippel Foundation, an American Heart Association National Grant-in-Aid (9950480N), NIH HL071834, and a Washington State Life Sciences Discovery Award to the Northwest Institute for Genetic Medicine. DSK was supported by NIH 1F31MH101905-01, T32HL007312 and AHA 16POST27250048. JHK was supported by NCRR Grant KL2 TR000421.

Abbreviations

- CHD

congenital heart disease

- CPB

cardiopulmonary bypass

- DHCA

deep hypothermic circulatory arrest

- ECMO

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- LOS

length of stay

- MAF

minor allele frequency

- MBL

mannose-binding lecithin

- MIM

Mendelian Inheritance in Man

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented at the Centennial Meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery in Boston, MA

Conflicts of Interest: DMM-M has presented lectures on 22q11.2 deletion syndrome for Natera. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bellinger DC, Jonas RA, Rappaport LA, et al. Developmental and neurologic status of children after heart surgery with hypothermic circulatory arrest or low-flow cardiopulmonary bypass. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(9):549–555. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellinger DC, Wypij D, duPlessis AJ, et al. Neurodevelopmental status at eight years in children with dextro-transposition of the great arteries: The Boston Circulatory Arrest Trial. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2003;126(5):1385–1396. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(03)00711-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaynor JW, Nord AS, Wernovsky G, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype modifies the risk of behavior problems after infant cardiac surgery. PEDIATRICS. 2009;124(1):241–250. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ikeda K, Sannoh T, Kawasaki N, Kawasaki T, Yamashina I. Serum lectin with known structure activates complement through the classical pathway. J Biol Chem. 1987;262(16):7451–7454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mogues T, Ota T, Tauber AI, Sastry KN. Characterization of two mannose-binding protein cDNAs from rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta): structure and evolutionary implications. Glycobiology. 1996;6(5):543–550. doi: 10.1093/glycob/6.5.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Super M, Thiel S, Lu J, Levinsky RJ, Turner MW. Association of low levels of mannan-binding protein with a common defect of opsonisation. The Lancet. 1989;2(8674):1236–1239. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91849-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sumiya M, Super M, Tabona P, et al. Molecular basis of opsonic defect in immunodeficient children. The Lancet. 1991;337(8757):1569–1570. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93263-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi L, Takahashi K, Dundee J, et al. Mannose-binding Lectin-deficient Mice Are Susceptible to Infection with Staphylococcus aureus. J Exp Med. 2004;199(10):1379–1390. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koroglu OA, Onay H, Erdemir G, et al. Mannose-Binding Lectin Gene Polymorphism and Early Neonatal Outcome in Preterm Infants. Neonatology. 2010;98(4):305–312. doi: 10.1159/000291487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Auriti C, Prencipe G, Caravale B, et al. MBL2 gene polymorphisms increase the risk of adverse neurological outcome in preterm infants: a preliminary prospective study. Pediatr Res. 2014;76(5):464–469. doi: 10.1038/pr.2014.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaynor JW, Gerdes M, Zackai EH, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype and neurodevelopmental sequelae of infant cardiac surgery. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2003;126(6):1736–1745. doi: 10.1016/S0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaynor JW, Wernovsky G, Jarvik GP, et al. Patient characteristics are important determinants of neurodevelopmental outcome at one year of age after neonatal and infant cardiac surgery. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2007;133(5):1344–1353.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.10.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim DS, Kim JH, Burt AA, et al. Patient genotypes impact survival after surgery for isolated congenital heart disease. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2014;98(1):104–10. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.03.017. discussion110–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim DS, Kim JH, Burt AA, et al. Burden of potentially pathologic copy number variants is higher in children with isolated congenital heart disease and significantly impairs covariate-adjusted transplant-free survival. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2015 Nov; doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.09.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim DS, Stanaway IB, Rajagopalan R, et al. Results of genome-wide analyses on neurodevelopmental phenotypes at four-year follow-up following cardiac surgery in infancy. Crawford DC, ed. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9):e45936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wechsler D. Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence™. Third. Pearson Clinical; 2002. WPPSI™ - III. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beery KE, Buktenica NA. Beery-Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration. Sixth. Pearson Clinical; 2010. the (BEERY™ VMI) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. ASEBA® Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 1.5-5 (CBCL/1.5-5) and ASEBA Caregiver-Teacher Report Form for Ages 1.5-5 (C-TRF) Psychological Assessment Resources; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazefsky CA, Anderson R, Conner CM, Minshew N. Child Behavior Checklist Scores for School-Aged Children with Autism: Preliminary Evidence of Patterns Suggesting the Need for Referral. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;33(1):31–37. doi: 10.1007/s10862-010-9198-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2007;81(3):559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaynor JW, Kim DS, Arrington CB, et al. Validation of association of the apolipoprotein E ε2 allele with neurodevelopmental dysfunction after cardiac surgery in neonates and infants. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2014;148(6):2560–2566. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.07.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kosoy R, Nassir R, Tian C, et al. Ancestry informative marker sets for determining continental origin and admixture proportions in common populations in America. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(1):69–78. doi: 10.1002/humu.20822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38(8):904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clancy RR, McGaurn SA, Wernovsky G, et al. Preoperative risk-of-death prediction model in heart surgery with deep hypothermic circulatory arrest in the neonate. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2000;119(2):347–357. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(00)70191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yager PH, You Z, Qin T, et al. Mannose binding lectin gene deficiency increases susceptibility to traumatic brain injury in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28(5):1030–1039. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orsini F, Villa P, Parrella S, Zangari R, Zanier ER. Targeting mannose binding lectin confers long lasting protection with a surprisingly wide therapeutic window in cerebral ischemia. Circulation. 2012 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.103051/-/DC1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Longhi L, Orsini F, De Blasio D, et al. Mannose-Binding Lectin Is Expressed After Clinical and Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury and Its Deletion Is Protective*. Critical Care Medicine. 2014;42(8):1910–1918. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cervera A, Planas AM, Justicia C, et al. Genetically-Defined Deficiency of Mannose-Binding Lectin Is Associated with Protection after Experimental Stroke in Mice and Outcome in Human Stroke. Meisel A, ed. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(2):e8433–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bilgin YM, Brand A, Berger SP, Daha MR, Roos A. Mannose-binding lectin is involved in multiple organ dysfunction syndrome after cardiac surgery: effects of blood transfusions. Transfusion. 2008;48(4):601–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collard CD, Shernan SK, Fox AA, et al. The MBL2 “LYQA secretor” haplotype is an independent predictor of postoperative myocardial infarction in whites undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Circulation. 2007;116(11 Suppl):I106–I112. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.679530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frakking FNJ, Brouwer N, Zweers D, et al. High prevalence of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) deficiency in premature neonates. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;145(1):5–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03093.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xue J, Liu A-H, Zhao B, Si M, Li Y-Q. Low levels of mannose-binding lectin at admission increase the risk of adverse neurological outcome in preterm infants: a 1-year follow-up study. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2015;29(9):1425–1429. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2015.1050372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Speletas M, Gounaris A, Sevdali E, et al. MBL2 Genotypes and Their Associations with MBL Levels and NICU Morbidity in a Cohort of Greek Neonates. Journal of Immunology Research. 2015 Mar;:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2015/478412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaynor JW, Mahle WT, Cohen MI, et al. Risk factors for mortality after the Norwood procedure. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;22(1):82–89. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.