Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to examine knowledge, awareness, and support for campus smoke-free policies.

Participants

1,256 American Indian tribal college students from three tribal colleges in the Midwest and Northern Plains.

Methods

Data are from an observational cross-sectional study of American Indian tribal college students, collected through a web-based survey.

Results

Only 40% of tribal college students reported not being exposed to second hand smoke in the past 7 days. A majority of nonsmokers (66%) agreed or strongly agreed with having a smoke-free campus, while 34.2% of smokers also agreed or strongly agreed. Overall, more than a third (36.6%) of tribal college students were not aware of their campus smoking policies.

Conclusions

Tribal campuses serving American Indian students have been much slower in adopting smoke-free campus policies. Our findings show that tribal college students would support a smoke-free campus policy.

Keywords: American Indian, campus tobacco free policies, secondhand smoke, tribal campuses

Introduction

It is well recognized that tobacco use in any form, active or passive, is a substantial health risk.1 Additionally, studies have shown that there are no safe levels of exposure to second hand smoke (SHS), a Class-A carcinogen.2–4 In response to this knowledge, the American College Health Association (ACHA) adopted a “no tobacco use” policy and encourages colleges to be ardent in achieving a 100% campus-wide (inside and outside) tobacco free environment.5 Since this position statement, 1,577 US colleges and universities have instituted smoke-free campus policies, 1,078 of these colleges and universities are 100% tobacco free (smokeless tobacco is also banned) and 710 of these colleges ban the use of e-cigarettes on campus.6 For those institutions without a complete ban, there is wide variation in antismoking policies as well as related issues with students’ compliance. Since the majority of campuses have limited enforcement efforts of these policies, student compliance with any smoking restrictions is low. While these efforts have been successful among US colleges, as of 2017, only 5 tribal colleges have become smoke or tobacco free (two are e-cigarette free)6 out of 37 total tribal colleges, serving approximately 30,000 full and part-time American Indian students across all campuses.

Cigarette smoking remains the leading cause of preventable death worldwide.1,7 In 2014, the annual prevalence of cigarette usage in the past month among full-time US college students was 13%.8,9 Although the smoking prevalence has declined in the past decade for all other racial/ethnic minorities, it has increased among American Indian adults.10 Furthermore, recent data for American Indian adults depicts the smoking prevalence is highest in the Northern Plains (approximately 42%) and lowest in the Southwest (14%–18%).11 While limited data exist on smoking rates of American Indian tribal college students, the existing data suggest that the rates are much higher than those of US college students,12,13 making SHS exposure and smoking cessation in this population a vital issue. Smoke-free campus policies have been shown to be an effective way of addressing SHS exposure and enhancing quitting and smoking cessation on college campuses.14

The data were part of a larger observational study that describes the epidemiology of smoking (experimentation, initiation, addiction, cessation, etc) among tribal college students.15,16 The purpose of this study was to examine knowledge and awareness of campus smoke-free policies and also estimate tribal college students’ exposure to SHS. The overall study aim was to examine the natural history of cigarette smoking among tribal college students. Specifically, to estimate the smoking prevalence, uptake, and cessation rates in this population.

Methods

Study design and population

Data are from an observational cross-sectional study of American Indian tribal college students.16,17 The focus of our recruitment strategy for this study was to recruit all incoming freshman at three participating tribal colleges in the Midwest and Northern Plains region.16 All three participating colleges offer the Associate Degree and two institutions also offer Bachelor’s degrees. The student enrollment numbers also vary with one college having less than 500 students, the second school with an enrollment between 500–1,000 and the third tribal college with an enrollment between 1,000 and 1,500. More than 250 different tribes or nations are represented by these three tribal colleges. Initially, all tribal college campuses were invited to participate in an observational survey of health behaviors, with only 3 tribal colleges responding to participate. A total of 1,256 unique American Indian tribal college students participated. Our inclusion criteria were individuals who: (1) self-identified as American Indian; (2) were enrolled in one of the participating tribal colleges; and (3) were age 18 or older at the time of survey.16

An email message was sent to students inviting them to complete the web-based survey which was available twice per year (April and October) for one month at each time point between 2011 and 2014.16 Students could also take the survey at the survey website. Each participant had unique email addresses, which was used to ensure that each participant only took the survey one time at baseline. Less than 1% of all the respondents were duplicates that had to be removed from the baseline data.

Information about the study was posted on flyers around campus. Participants provided electronically signed informed consent and were compensated with a $15 gift card for completing the online survey. All study procedures were approved by the University of Kansas Medical Center’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) as well as the respective IRBs at the participating tribal colleges.

The overall response rates per year were 15.3% (2011), 18.5% (2012), 18.5% (2013), and 32.1% (2014).16 These are true overall response rates using the total number of students enrolled at the three participant tribal colleges and were comparable across the three colleges.16 Our primary recruitment efforts focused on the freshman classes each year, therefore we obtained higher freshman response rates 13.8% (2011), 26.0% (2012), 34.0% (2013), and 64.3% (2014), representing the percentage of freshmen who participated in the study.16 The focus on freshmen was driven by the focus to conduct follow-up surveys as they progressed in school to examine changes in smoking as well as other behaviors. Freshmen are defined as new incoming students to the respective tribal colleges. The demographic characteristics of students who participated in this study were comparable to those of the larger student bodies on the tribal campuses.

Study variables

The online survey, the Tribal College Tobacco and Behavior Survey, consisted of questions regarding demographics, tobacco behaviors (patterns of use, quitting intentions, and history), smoking restrictions at home, work and school, exposure to SHS, perceptions of campus smoking, and desires for a smoke-free campus, as well as other health behaviors related to tribal college students’ health. All variables and information from the tribal college students were collected through the web-based surveys as self-reports.

Demographic variables

We collected information on gender, current living situation (on or off campus), type of program (2-year or 4-year degree), children or no children, current year in school, employment status, and where the respondent grew up (rural, urban/suburban, or reservation/tribal trust lands).16 Participants also provided information on parents’ educational status.16

Smoking status

The following questions were used to determine current smoking status, “Do you smoke cigarettes now?” with response categories of “every day, some days, and not at all.” Current smokers were respondents who either smoked every day or some days.

Current smoking home, work, and school policies

To examine existing smoking policies at students’ homes we asked the following question, “Which statement describes the rules about smoking inside where you live?” with response categories of “Smoking is not allowed anywhere or at any time inside where I live” and “Smoking is allowed inside where I live.” To examine existing smoking policies at students’ jobs we asked, “Which statement describes smoking inside where you work?” with response categories of “I am not currently working,” “Smoking is not allowed anywhere or any time where I work,” and “Smoking is allowed where I work.” To examine existing smoking policies at the tribal colleges participants attended, we asked “Which statement best describes smoking on your campus?” with the response categories of “Smoking is not allowed anywhere or any time on my campus,” “Smoking is allowed in some places or at some times on my campus,” “Smoking is allowed everywhere and at any time on my campus” and “I am not aware of any campus policy pertaining to smoking.”

Exposure to second hand smoke

To examine students’ exposure to SHS, we asked the following questions: “During the past 7 days, on how many days were you in the same room or car with someone who was smoking cigarettes?” with response categories of “0 days”, “1 or 2 days” and “3–7 days.” “How many of your five closest friends smoke cigarettes?” with response categories of “None”, “1–2” and “3–5.” “Not including yourself, does anyone in your home currently smoke cigarettes?” with response categories of “Yes” and “No.”

Intention to quit smoking

To assess participants’ intention to quit smoking, we asked the following question: “Are you seriously thinking about quitting smoking? With response categories of: 1) Yes, within the next 30 days, 2) Yes, within the next 6 months, 3) Yes within the next year, 4) Yes, but not within the next year, 5) Not sure, and 6) No. We combined the last 4 response categories (3–6) into the “No plan to quit smoking” group since these smokers had no intention to quit within the next 6 months.

Campus smoking policies and students’ perceptions of smoking on campus

To examine students’ knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about their campus’ smoking policies we asked the following questions, “How did you find out about your campus’s smoking policy?” The response categories were, “Never learned,” “through written communication,” and “through verbal communication.” “What percentage of students do you think know about your campus’ smoking policy?” with response categories of “0%–20%,” “21%–40%,” 41%–60%,” “61%–80%,” and “81%–100%.” Additionally, we asked students to respond to the following statement, “I would like my campus to be smoke free,” the response categories were “Strongly disagree,” “Disagree,” “Neutral,” “Agree,” and “Strongly Agree.” To gauge students’ perceptions of smoking rates on campus we asked, “What percent of students at your college do you think smoke cigarettes?” with response categories of “0%–20%,” “21%–40%,” 41%–60%,” “61%–80%,” and “81%–100%.”

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages, were used for discrete variables. Similarly, continuous variables were described using mean and standard deviation. Appropriate p values for bivariate associations among discrete variables were reported using the chi-square test. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (Copyright (c) 2002–2010 by SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA.). Statistically significant associations were identified by p values of less than .05.

Results

All participants, 1,256 American Indian tribal college students, were included in these analyses. The mean age of student participants was 25.5 years and 57.8% were women. While all students self-identified as American Indian, 25.4% identified as multiracial (American Indian and another race or ethnicity). Most students (61.3%) indicated that they grew up on reservation or tribal trust land. The majority of students reported that they were single (82%). While 32.1% of students reported having children, 39.1% were living in the same home as children under the age of 18. Approximately 57% of students lived on campus, 44% were in their first year of college, and 59% were working towards a 4-year degree. When asked if they were attending a college in a different state than their high school, 58% of students identified as “out-of-state.” Roughly 26% of students were working while attending college. The overall smoking prevalence was 34.7%. There were differences by region (nearly 44% in the Northern Plains and approximately 28% in the Southern Plains).

Table 1 shows tribal college students exposure to SHS and their knowledge of and attitudes towards campus smoke free policies by their self-identified smoking status. More than 58% of all students stated that they had been in the same room or in a car with a smoker at least once within the last 7 days, and 54% of students reported that they spent some or all of their time around people who smoke. Among current smokers, only 17.3% were not in the same car or room with another smoker in the last 7 days, while 53.6% of nonsmokers were not in the same car or room with a smoker in the last 7 days.

Table 1.

Tribal college students’ exposure to second hand smoke and knowledge of attitudes towards campus smoke free policies by smoking status (n = 1,256).

| Variables | All Students Total N (%) | Smokers N (%) | Nonsmokers N (%) | p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of days, during past 7 days, students were in the same room or car with a smoker | ||||

| 0 days | 497 (41.4) | 70 (17.3) | 427 (53.6) | < .0001** |

| 1–2 days | 316 (26.3) | 111 (27.5) | 205 (25.8) | |

| 3–7 days | 387 (32.3) | 223 (55.2) | 164 (20.6) | |

| Number of students’ 5 closest friends who smoke cigarettes | ||||

| 0 | 323 (27.0) | 52 (12.9) | 271 (34.1) | < .0001** |

| All 1–2 | 486 (40.6) | 139 (34.6) | 347 (43.7) | |

| 3–5 | 387 (32.4) | 211 (52.5) | 176 (22.2) | |

| Amount of time students spent with people who smoke cigarettes | ||||

| Never | 553 (46.0) | 99 (24.6) | 454 (56.8) | < .0001** |

| Some time | 360 (30.0) | 133 (33.0) | 227 (28.4) | |

| All the time | 289 (24.0) | 171 (42.4) | 118 (14.8) | |

| Students’ who live with a current smoker | ||||

| Yes | 434 (36.3) | 200 (49.8) | 234 (29.4) | < .0001** |

| No | 763 (63.7) | 202 (50.2) | 561 (70.6) | |

| Students’ home smoking rules | ||||

| Smoking not allowed | 957 (79.6) | 295 (72.7) | 662 (83.1) | < .0001** |

| Smoking allowed | 246 (20.4) | 111 (27.3) | 135 (16.9) | |

| Students’ work smoking policies | ||||

| Do not work | 785 (65.4) | 255 (63.0) | 530 (66.6) | .0209** |

| Smoking not allowed | 219 (18.2) | 67 (16.5) | 152 (19.1) | |

| Smoking allowed | 197 (16.4) | 83 (20.5) | 114 (14.3) | |

| Students’ perception of their campus’ current smoking policy | ||||

| Smoking not allowed | 120 (10.0) | 38 (9.5) | 82 (10.3) | .013** |

| Smoking allowed in some places*** | 730 (60.9) | 261 (65.4) | 469 (58.6) | |

| Smoking allowed everywhere | 232 (19.3) | 76 (19.0) | 156 (19.5) | |

| Not aware of policy | 117 (9.8) | 24 (6.0) | 93 (11.6) | |

| How students learned about their campus’ smoking policy | ||||

| Never learned | 460 (36.6) | 161 (36.9) | 299 (36.5) | .9672 |

| Written communication | 526 (41.9) | 183 (42) | 343 (41.8) | |

| Verbal communication | 270 (21.5) | 92 (21.1) | 178 (21.7) | |

| Students’ perception of the percent of students who know about campus’ smoking policy | ||||

| 0%–20% | 157 (15.9) | 51 (15.3) | 106 (16.3) | .0097** |

| 21%–40% | 218 (22.1) | 62 (18.6) | 156 (24) | |

| 41%–60% | 243 (24.7) | 83 (24.9) | 160 (24.6) | |

| 61%–80% | 199 (20.2) | 62 (18.6) | 137 (21.0) | |

| 81%–100% | 168 (17.1) | 76 (22.8) | 92 (14.1) | |

| Students’ response to statement “I would like my campus to be smoke free” | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 120 (12.2) | 68 (20.4) | 52 (8.0) | < .0001** |

| Disagree | 134 (13.7) | 73 (21.9) | 61 (9.4) | |

| Neutral | 186 (18.9) | 79 (23.7) | 107 (16.5) | |

| Agree | 248 (25.3) | 65 (19.5) | 183 (28.2) | |

| Strongly agree | 294 (29.9) | 49 (14.7) | 245 (37.8) | |

| Students’ perception of the percent of students at their school who smoke cigarettes | ||||

| 0%–20% | 64 (6.5) | 20 (6.0) | 44 (6.7) | .9878 |

| 21%–40% | 215 (21.8) | 73 (22.0) | 142 (21.7) | |

| 41%–60% | 383 (38.9) | 132 (39.8) | 251 (38.4) | |

| 61%–80% | 268 (27.2) | 89 (26.8) | 179 (27.4) | |

| 81%–100% | 55 (5.6) | 18 (5.4) | 37 (5.7) | |

p refers to comparison between smokers and nonsmokers

Significant variables

The correct answer for all campuses

Current smokers had a larger percentage of friends who smoked. When asked about the number of their closest friends who smoked, 52.5% of smokers identified having 3–5 friends who smoke, 34.6% had 1–2 friends who smoked, and only 12.9% had no close friends who smoked. While nonsmokers had fewer close friends who smoked, 22.2% still had 3–5 friends who smoked and 43.7% had 1–2 friends who smoked. When asked about the amount of time students spent with people who smoke cigarettes, 24.6% of smokers and 56.8% of non-smokers reported never spending time with people who smoke cigarettes. While 75.4% of smokers and 43.2% of nonsmokers spent some time or all of their time with people who smoke. We examined students’ home smoking rules and found that the vast majority of smokers (72.7%) and nonsmokers (83.1%) did not allow smoking in their homes. Smokers were a little more likely (20.5%) to work jobs that allowed smoking than nonsmokers (14.3%), but this was not statistically significant.

Next we examined students’ knowledge of their college’s smoking policy. When asked about their college’s current smoking policy, only 65.4% of smokers and 58.6% of nonsmokers were correct in identifying their college’s current smoking policy—smoking is allowed in some places on all of the college campuses with whom we worked. When asked about how students learned about their colleges’ smoking policy, responses were similar regardless of smoking status; 36.9% of smokers and 36.5% of nonsmokers reported never learning about the policy, while 42.0% of smokers and 41.8% of non-smokers learned about the policy through written communication, and 21.1% of smokers and 21.7% of nonsmokers learned about their campus’ smoking policy through verbal communication (these results were not statistically significant).

We also looked at students’ attitudes towards a smoke-free college campus policy. We asked students to respond to the statement, “I would like my campus to be smoke free.” An overwhelming number of nonsmokers (66%) agreed or strongly agreed with this statement. Only 17.4% of nonsmokers disagreed or strongly disagreed and 16.5% were neutral about having a smoke-free campus. Among smokers, 34.2% strongly agreed or agreed with having a smoke-free campus, 42.3% strongly disagreed or disagreed, and 23.7% were neutral. When asked about the perceived smoking rate on campus, both smokers and nonsmokers had similar perception rates, with 32.2% of smokers and 33.1% of nonsmokers overestimating the smoking rates on their campus to be between 61% and 100% (these results were not statistically significant).

Table 2 provides a summary of the smoking/tobacco policies at our three participant schools. All of the smoking policies appear in the colleges’ respective student handbooks. All schools had partial smoking restrictions that encompassed the buildings and a stated perimeter around the buildings (College A and B with 25 feet perimeters and College C with a 50 feet perimeter). College B’s smoking policy does state that it is a “smoke-free” campus, however as stated above, its policy only applied to the buildings and a perimeter around them. While all of the policies included cigarettes, only College A and C included smokeless tobacco and e-cigarettes, and only College C’s policy expressly forbade the use of hookahs in its residence hall policies. The policies for two of the colleges reference a designated smoking area, but College B’s policy only mentions outdoor ashtrays. Religious exemptions are only noted in College C’s policy and the exemption states, “A student must receive prior approval from the Director of Housing to burn material for religious purposes.” (Citation omitted to protect the anonymity of the school.) College B is the only college to clearly describe a possible sanction for violation of its smoking policy, which includes possible suspension or dismissal from college. While College C has a $50 fine listed for violation of its policy, the fine is discussed in the fire hazards section of the student handbook and appears to be in reference to “heat-producing appliances” found in students’ door rooms. College A’s policy does not include a stated sanction for individuals, however it does state that “consistent violation” of the smoking policy could result in the campus becoming smoke-free.

Table 2.

Summary of participant tribal colleges’ smoking/tobacco policies.

| Policy | College A | College B | College C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tribal college policy includes: | |||

| Cigarettes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Smokeless tobacco | Yes | No | Yes |

| Electronic cigarettes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Smoking is restricted in the following locations: | |||

| Campus buildings | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Perimeter around buildings | 25 feet | 25 feet | 50 feet |

| Campus grounds | No | No | No |

| Designated outdoor smoking areas | Yes | No | Yes |

| Religious exemptions noted | No | No | Yes |

| Sanction/Enforcement noted | No | Yes | No |

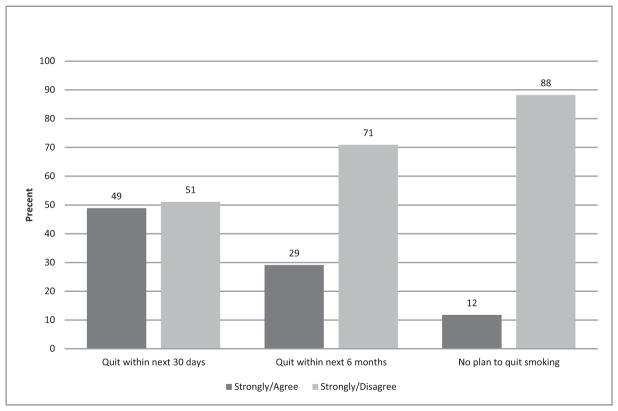

Figure 1 shows the opinions of students who smoke daily regarding their support for their campus becoming smoke-free by their intention to quit smoking. Students who said they “are seriously thinking about quitting smoking within 30 days” agree more frequently (49%) with the statement,” I would like my campus to be smoke free” than those who are seriously thinking of quitting within the next 6 months (29% agree), or those who have no current intention to quit smoking (12%). These differences are statistically significant (p < .0001).

Figure 1.

Opinions of daily smokers of campus becoming smoke-free by intention to quit smoking.

Comment

This study has four main findings: 1) a sizeable percentage of nonsmokers at participating tribal colleges were exposed to SHS; 2) most students were familiar with their campuses’ smoking policies, but believed that their fellow students were not; 3) most students said they would like their campus to be smoke free; and 4) smokers who planned on quitting in the next 30 days were more likely to want their campus to be smoke-free.

Tribal college students in this study reported exposure to substantial amounts of SHS. While their exposure to SHS is high, we do not know the extent to which the exposure occurs on-campus versus off-campus. Exposure to SHS could take place in off-campus housing or during leisure activities with friends. Still, due to the high prevalence of smoking among the respondents and the gaps that exist in the colleges’ current smoking policies, exposure to SHS at the colleges remains a significant public health issue.

The majority of student respondents who did not smoke and a third of smokers indicated that they would like their campus to be smoke free, compared to other nontribal college students who reported that 52% of smokers “not opposing” a tobacco-free campus policy.18 Not only does a change in policy make good sense from a public health perspective, but it reflects the will of the student body. Although the number of smoke-free campuses tripled between 2010 to 2016, tribal colleges have not experienced similar policy changes.19

There was low level of awareness among tribal college students regarding the current smoking policy on their respective campuses. Roughly four in 10 students were unable to identify the current smoking policy at their college from a list of four options. The majority of student respondents thought that their peers did not know the current policy, and an overwhelming majority of students thought that the prevalence of smoking among students was higher than the actual rate. This may be indicative of a “smoking-positive culture”20 at our partner colleges. Students in our sample were more likely to see other students smoking on campus, regardless of campus tobacco policies.

Enforcement strategies related to tobacco policies varied across the campuses. Although the student handbook for all three campuses included a description of the indoor smoke-free policies, not all campuses included enforcement. One campus had an enforcement of a sanction of $50 fine for each violation whereas the other two tribal colleges did not have any description of a fine or other enforcement strategies.

The smoking prevalence among students at the three tribal colleges studied was 50% greater than that for all full-time college students in the US.16 Considering this alarming fact, the exposure of nonsmokers to SHS, and the desire on behalf of students for a smoke-free campus, it is somewhat surprising that these three schools have not adopted more robust smoking policies. While they all prohibit smoking in campus buildings and an outdoor perimeter surrounding them of at least 25 feet, they all permit smoking in designated outdoor areas. One college provides an exemption for religious use of tobacco, and one has a stated enforcement policy.

Nearly half of the smokers who indicated a willingness to quit within the next 30 days supported their campus becoming smoke-free. The level of support for a smoke-free campus declined with weaker levels of intention to quit smoking. Consequently, programs motivating current smokers into making a quit attempt may also help in raising support for implementing a smoke-free campus. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that a complete smoking ban on campus reduces cigarette consumption and smoking prevalence twice as much as a partial ban.21,22

Only five of the 37 (13.5%) tribal colleges in the US have adopted smoke-free campus policies. The findings that many tribal college students who are nonsmokers are exposed to SHS at their schools and that a majority of all students desire a smoke-free campus sets the stage for policy recommendations to the 86.5% of tribal colleges that do not currently have smoke-free campus policies in place.

American Indian tribal colleges are urged to adopt the ACHA guidelines. These guidelines go beyond simply banning smoking on campus. They specifically state that smoking policies should also include explicit statements about promulgation (including signage to alert visitors to the campus that smoking is prohibited) and enforcement of the rules. ACHA also suggests that colleges have an obligation to their students to promote smoking prevention and to offer and promote programs and services to help students who smoke to quit. Considering the high prevalence of tobacco use among American Indian college students, access to prevention and cessation programs through student health services at tribal colleges would be highly desirable. Results from this study as well as other surveys of tribal colleges demonstrating strong support can assist administrators with consensus building and help move the institution towards the adoption of a smoke-free campus.

It is clear that this group of students has high exposure to SHS and a desire to limit their exposure through appropriate policies addressing smoking and tobacco on campus. Given that approximately 80% of our participants banned smoking in their homes, there is clear support for implementing a similar policy on their college campuses. Further research will help determine the most appropriate ways to implement these policies.

Limitations of this study include the self-reported nature of the data and somewhat low response rates, as well as nonresponse bias. We cannot say that the three schools are representative of all the tribal colleges that have not yet fully implemented smoke-free campus polices, and we cannot make any generalizations about tribal college smoking policies from our data. However, considering the large sample of American Indian tribal college students surveyed for this study, we feel comfortable making generalizations about the behaviors and attitudes of the tribal college students. Although we invited all tribal colleges to participate, only 3 institutions participated in our observational survey. Therefore, results from this study should take into consideration nonresponse bias and potential differences among tribal college students from nonparticipating colleges.

Despite these limitations, since the majority of published studies present data for nontribal college students, this study is significant for providing relevant data in Tribal College student populations. Because limited information is available for Tribal Colleges, further research that identifies unique barriers that exists on these campuses is crucial. Additional areas of research include interventional studies of campus smoke-free policies since this was an observational survey. Furthermore, inclusion of community colleges and nontraditional 4-year institutions would provide information on more diverse student populations who are at higher risk of exposure to SHS.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (P20 MD004805, RWJF–72086, U54 CA154253).

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potera C. Smoking and secondhand smoke. Study finds no level of SHS exposure free of effects. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(11):A474. doi: 10.1289/ehp.118-a474a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strulovici-Barel Y, Omberg L, O’Mahony M, et al. Threshold of biologic responses of the small airway epithelium to low levels of tobacco smoke. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(12):1524–32. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0294OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American College Health Association. Position statement on Tobacco on college and university campuses. Hanover, MD: American College health Association; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation. [Accessed July 1, 2015];Smokefree and Tobacco-Free U.S. and Tribal Colleges and Universities. 2015 http://www.no-smoke.org/pdf/smokefreecollegesuniversities.pdf.

- 7.World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.College students’ use of marijuana on the rise, some drugs declining. Ann Arbor, MI: Monitoring the Future; 2014. [press release] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA. Monitoring the future National Survey Results on drug use, 1975–2014: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research: The University of Michigan; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martell B, Garrett B, Caraballo R. Disparities in Adult Cigarette Smoking—United States, 2002–2005 and 2010–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:753–758. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6530a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cobb N, Espey D, King J. Health behaviors and risk factors among American Indians and Alaska Natives, 2000–2010. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(Suppl 3):S481–489. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solobig Z, Pokhrel K, Parks I, Bullock A, Hamasaka L, Williams L. Tribal college health initiative: A study of Tobacco-related health disparities in three different tribes. Washington, DC: Legacy; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward BW, Ridolfo H. Alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use among Native American college students: an exploratory quantitative analysis. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46(11):1410–19. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.592437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mamudu HM, Veeranki SP, Kioko DM, Boghozian RK, Littleton MA. Exploring support for 100% College Tobacco-free policies and tobacco-free campuses among college Tobacco users. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015 doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faseru B, Daley CM, Gajewski B, Pacheco CM, Choi WS. A longitudinal study of tobacco use among American Indian and Alaska Native tribal college students. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):617. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi W, Nazir N, Pacheco C, et al. Recruitment and baseline characteristics of American Indian tribal college students participating in a tribal college tobacco and behavioral survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(6):1488–93. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faseru B, Daley CM, Gajewski B, Pacheco CM, Choi WS. A longitudinal study of tobacco use among American Indian and Alaska Native tribal college students. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:617. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braverman MT, Hoogesteger LA, Johnson JA, Aaro LE. Supportive of a smoke-free campus but opposed to a 100% tobacco-free campus: Identification of predictors among university students, faculty, and staff. Prev Med. 2017;(94):20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koh H. Place matters for tobacco control. JAMA. 2016;316(7):700–701. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.10537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chapman S, Freeman B. Markers of the denormalisation of smoking and the tobacco industry. Tob Control. 2008;17(1):25–31. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.021386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fichtenberg CM, Glantz SA. Effect of smoke-free workplaces on smoking behaviour: systematic review. BMJ. 2002;325(7357):188. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7357.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fallin A, Roditis M, Glantz SA. Association of campus tobacco policies with secondhand smoke exposure, intention to smoke on campus, and attitudes about outdoor smoking restrictions. AJPH. 2015;105(6):1098–1100. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]