Abstract

Recent studies have documented frequent use of female sex workers among Latino migrant men in the southeastern United States, yet little is known about the context in which sex work takes place, or the women who provide these services. As anthropologists working in applied public health, we use rapid ethnographic assessment as a technical assistance tool to document local understandings of the organization and typology of sex work and patterns of mobility among sex workers and their Latino migrant clients. By incorporating ethnographic methods in traditional public health needs assessments, we were able to highlight the diversity of migrant experiences and better understand the health needs of mobile populations more broadly. We discuss the findings in terms of their practical implications for HIV/STD prevention and call on public health to incorporate the concept of mobility as an organizing principle for the delivery of health care services.

Keywords: mobility, migrant health, sex work, applied public health, HIV/AIDS, sexually transmitted disease

INTRODUCTION

“Immigration policies are a major barrier to Latino health. We can do a lot to improve access if they [migrant workers] could be part of the regular infrastructure. They are not integrated into society. When you push people out of the mainstream, they go off into different venues to get sex and other needs met.” –Social Worker, North Carolina Department of Health

From 2000 to 2010, the Latino population in the United States grew by 43%, accounting for the majority of growth in the total population (Ennis, Ríos-Vargas, and Nora 2010; Passel, Cohn, and Lopez 2011). Although a large proportion of Latinos still live in states with established Latino populations such as California, Florida and New York, their share has been rapidly growing in other places, most notably in the southeastern United States, where states such as Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina and South Carolina more than doubled their Latino population sizes. North Carolina, for example, experienced a rapid increase in the Latino population, from 1.7% in 1990 to 7% of the total population in 2008, a growth of more than 400% (US Census Bureau 2009).

The migration of Latinos into these southeastern states has been driven by employment opportunities in construction and agriculture. As a result, the demographic makeup in these “new settlement” areas of the South differs from that of more established Latino communities across the country, with Latinos more likely to be young, male, unmarried, foreign-born, and recent arrivals. Public health studies focusing on the South have documented the social dimensions that facilitate exposure to sexual risk for these men (Painter 2008). Many have focused on the frequent use of sex workers among migrant Latino men and subsequent increased risk for HIV/STD infections (Sena et al. 2010; Parrado, Flippen and McQuiston 2004; Rhodes et al. 2010; Viadro and Earp 2000). For instance, Parrado and Flippen (2010) found that migration to the United States was associated with a younger age of sexual debut and that sexual initiation was more likely to take place with a sex worker. Knipper and colleagues (2007) observed that in rural North Carolina, 32.5% of Latino men unaccompanied by female partners and 9.5% of Latino men with partners reported providing money or other goods in exchange for sex within the past three months. Another study reported that all Latino migrants identified as having syphilis during an outbreak in Alabama were found to have had sex with female sex workers (Paz-Bailey et al. 2004).

A few studies have highlighted the social dimensions that facilitate these men’s exposure to sexual risk. Apostolopoulos and colleagues (2006) found that Mexican male migrant laborers in South Carolina experienced high levels of social isolation, anxiety and depression, and reported high rates of risky sexual and substance abuse behaviors. Others have shown that the heightened patronage of sex workers may not be similar to practices in migrants’ countries of origin, reporting that unaccompanied migrant men, while in the United States, have more lifetime sex partners, more extramarital sex, and more sex with sex workers than men who are accompanied by their wives (Kissinger et al. 2012; Organista, Carrillo, and Ayala 2004; Pulerwitz, Izazola-Licea, and Gortmaker 2001; Viadro and Earp 2000). The extant literature referenced here suggests that individual and structural characteristics within the context of the migratory experience itself significantly influence men’s risk behavior, and that patronage of sex workers is associated with the social environment of migrant workers.

There are few data available on the organization of sex work in the southeastern United States; that is, the localized structures and processes through which sex is exchanged for money in what is generally regarded as a commercial transaction. Studies carried out in the 1990s largely addressed female sex work in conjunction with crack cocaine use in large urban areas such as Atlanta (Sterk 1999). An ethnographic study in Florida described the context of female sex work in agricultural areas, noting that sex workers with a history of substance abuse often canvassed large areas in search of clients or travelled to migrant camps to solicit men (Bletzer 2003). More recent studies with migrant farmworkers indicate that some sex workers work alone, while others appear to be housed in brothels and are moved routinely throughout the South and along migrant labor streams (NC Farmworker Health Program 2000; Parrado et al. 2004; Polaris Project 2009; Rhodes et al. 2010, 2012; Vissman et al. 2009). Rhodes and colleagues (2012), for instance, found differing structures of sex work with distinct referral processes among Latinos in North Carolina, including sex workers who operate out of bars, work for controllers, and function independently.

To better understand the structure and context of sex work, the social and structural dimensions that facilitate exposure to sexual risk, and the potential mechanisms for effective intervention among highly mobile and hidden populations, we conducted a rapid ethnographic assessment (REA) to obtain the views of health and social service providers. Our findings suggest that there is substantial diversity in patterns and experiences of mobility for both migrant men and sex workers. Latino migrant workers in North Carolina, a vast majority of who are unauthorized, were reported to have high rates of mobility which reduced their access to health care and contributed to their engagement with varied types of sex work services. Providers indicated that sex work in the area is characterized by several different factors including the location in which sex work takes place, the demographics of sex workers, the organizational structure of sex work, and the patterns of mobility associated with these structures. Results also suggest that available health and social services appear to be tailored for migrant men and sex workers who are less mobile (i.e. farmworkers with H-2A visas, street-based sex workers) as compared to unauthorized men and sex workers who move regularly and who may be part of multiple sexual networks.

Based on our findings, we advocate for more ethnographically grounded, long-term approaches to understanding mobility as an organizing principle in public health research and practice. Accessing highly mobile populations, especially those involved in activities that are hidden and criminalized, with health and other services is complex and challenging (Abrams 2010; Braunstein 1993; Singer 1999). But involvement in these activities and the elevated levels of mobility associated with them necessitates the urgent need to provide basic access to health and social services to these populations.

METHODS

Recognition of the need to address structural and social influences of poor health has been growing, with particular emphasis on understanding local health and cultural practices of populations impacted by severe health inequities (Krieger 2008; Marmot and Wilkinson 1999; Navarro 2004; CSDH 2008). The focus on distal causes of disease has propelled health research to include interdisciplinary and social science approaches. Qualitative research, in turn, is gaining credence in applied public health as a way to explore the root causes of health inequities as well as people’s understandings and experiences of health policy, interventions, and service delivery (Crabtree and Miller 1999; Hudelson 1994; Mays and Pope 1999).

Interest in using ethnographic approaches in health care research to conduct cultural analyses and to reach hidden populations is also growing. Although some scholars continue to debate over the differences between qualitative and ethnographic research (Beebe 2001; Handwerker 2001), many anthropologists working in applied public health settings argue that essential ethnographic data can be collected within the realities of programmatic time and budgetary constraints (Agar 2006; Bentley et al. 1988). Rapid qualitative and anthropological data collection methods have been used in development and health projects since the 1970s. These include rapid appraisal (Hildebrand 1979), rapid-feedback evaluation (Wholey 1983), rapid ethnographic assessment (Scrimshaw and Hurtado 1987), rapid evaluation methods (Anker et al. 1993), participatory rural appraisal (Chambers 1994a, 1994b), rapid assessment (Beebe 2001), and quick ethnography (Handwerker, 2001). Although these approaches have distinct origins, methods, and frameworks, they all emphasize the rapid collection and dissemination of information useful for key decision makers, the use of multi-disciplinary research teams, and triangulation to verify multiple data collection methods and sources (Harris, Jerome, and Fawcett 1997).

Drawing upon the principles of ethnography, REAs complement and offer alternatives to traditional public health data collection methods (i.e. surveys, medical record abstractions) and are a relatively inexpensive way to provide timely, practical feedback to state and local programs on factors that contribute to disease transmission (Needle et al. 2003). REAs help identify social and structural factors that contribute to poor health outcomes and are often used to conduct research on hidden, highly mobile, or hard-to-reach populations. Key characteristics of REAs are that they are focused on a few key questions and designed to achieve depth of understanding. They are carried out over a compressed period of time, with data collection usually taking several days to several weeks and analysis of data and report writing taking from a few weeks up to several months.

Supporters of REAs consider it an approach that is a compressed but not a diluted version of traditional ethnography that uses an integrated set of ethnographic methods, including mapping, observation, and key informant and focus group interviews (Needle et al. 2000, 2003, 2008; Parry et al. 2009; Trotter et al. 2001). Skeptics question the legitimacy of the method itself, arguing that the potential for misapplication of the technique is too great. In response, anthropologists who advocate for REAs maintain that such assessments are highly pragmatic given the lack of availability of qualified researchers, severe time and budgetary restrictions, and critical programmatic limitations in many applied public health settings (Manderson and Aaby 1992; Needle et al. 2000). Regardless of these divisive positions, REAs have a long history of success in international public health and have been used in recent years globally to document and describe the HIV/STD prevention needs of sex workers and clients (Aral and St. Lawrence 2002; Aral et al. 2005; Needle et al. 2008; Parry et al. 2009).

Our assessment did not attempt to address the entire scope of sex work within North Carolina; it focused on health and social service providers in a four-county area surrounding Raleigh to examine organizational patterns or typologies of sex work and engagement of migrant men as clients within these organizational patterns. Health care providers are key but grossly untapped sources of information because they regularly make difficult decisions about the delivery of adequate care in uncertain and tenuous immigration policy environments (cf. Heyman 2009; Holmes 2012; Willen, Mulligan, and Castañeda 2011). Because sex work and unauthorized migrant labor is hidden, front-line providers are often the only people who have access to those directly involved in such activities. Although their views and perspectives cannot be seen as fully representative of sex workers or migrant clients, providers are a source of invaluable information regarding the context and typology of sex work and unauthorized migrant labor as well as the impact of mobility on HIV/STD vulnerability.

The REA took place in May 2010, and was a collaborative effort of the North Carolina HIV/STD Prevention and Care Branch and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The assessment was carried out by an interdisciplinary team of public health professionals, including two anthropologists. The REA began with discussions with experts familiar with the migrant Latino population in North Carolina, the use of Google Earth to identify locations of agencies providing services to migrant Latinos, and a review of published and unpublished data to compile a social and demographic overview of the study area. Key informants, those likely to have knowledge of or contact with migrant laborers and female sex workers in a four-county area surrounding Raliegh, were sampled purposively and invited to participate in interviews. Individuals were selected from three broad sectors including community-based organizations, state and local HIV/STD and rural health programs, and legal services and law enforcement. In all, 28 key informant interviews were carried out: ten interviews were conducted with persons from community-based organizations (CBOs), nine with persons from state and county HIV and STD programs, five with persons from state and local rural health programs, and four with persons from legal services and law enforcement. These open-ended interviews, conducted at health and social service sites where providers worked and lasting from 60–180 minutes, elicited providers’ views on the typology of sex work, patterns of mobility among women involved in sex work, and the availability of and access to HIV/STD preventive services.

In addition, the team conducted field observations in truck stops, trailer parks, migrant worker camps, and apartment complexes where sex work is known to take place. Field notes taken during data collection were expanded into detailed notes and used for qualitative data analysis As is customary in rapid assessments, all four members of the team participated in the analysis and report writing, and a follow-up stakeholder meeting was held in North Carolina to present the findings outlined below and obtain feedback.

THE GEOGRAPHY OF SEX WORK: SEX WORKERS AND MIGRANT LATINO MEN IN THE US SOUTHEAST

Provider interviews revealed mobility in the context of migration and sex work in North Carolina is a multi-dimensional construct, encompassing such characteristics as frequency and timing of movement, direction and distance traveled, spatial or geographic range, and location, place, or destination. Although both migrant men and sex workers were said to experience a high degree of occupational mobility travelling substantial distances to find and secure work, there was considerable diversity in their patterns and experiences of mobility. A better understanding of the dynamics, characteristics, and key patterns in mobility—who, how, where and why travel occurs, and under what circumstances different groups of people come into social and sexual contact with each other—gives us additional insight into developing strategies to reach these hidden populations with critically needed services and interventions.

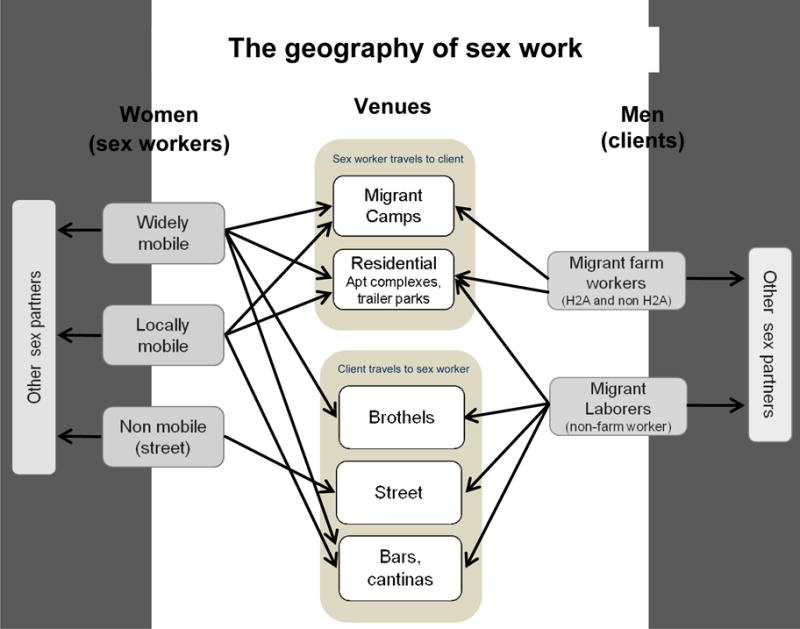

The diversity of these mobility experiences or patterns has significant bearing on the “geography of sex work,” the context in which sex workers and Latino men make contact with each other. Markets for sex work have traditionally emerged wherever there are large numbers of unaccompanied men who congregate for extended periods of time, and in North Carolina, providers suggested that migrant Latino men are perceived as prime clients by those involved in sex work because they carry cash, are seen as lonelier, and are believed to be less violent than other men. Key informant interviews and observations revealed that sex work services are available to Latino men in a diverse array of settings and venues, including migrant camps, brothels, cantinas and residential areas such as trailer parks and apartment complexes. As Latino men migrate into and out of North Carolina, sex work also adapts and develops structures and patterns to reach new clients. [Figure 1]

Figure 1.

The Geography of Sex Work

Mobility among migrant men

Large numbers of Latino men migrate to North Carolina for work each year, and provider interviews and a review of the literature indicate that the patterns of mobility and their daily experiences differs considerably based on whether they are temporary agricultural guest workers in possession of H-2A visas or unauthorized workers in the country for an undetermined length of time. Interactions with sex workers are also influenced by men’s legal and working status. For instance, providers conveyed that men with H-2A visas typically arrive in the United States at the beginning of the growing season and work for one grower until the end of their contract before returning home. These workers live in camps or dormitory style housing provided by growers located at the edge of agricultural fields in rural areas isolated from the nearest town. Their mobility, therefore, is relatively limited and primarily local; they eat, sleep, cook, do laundry, and work in the same location. Providers who conduct outreach at these farms described camp life as geographically and socially isolated, and often lonely and boring for the men who live there.

The vast majority of agricultural workers in North Carolina, however, are not H2-A visa holders; in 2010, only 8,905 of an estimated 69,150 workers held H-2A visas (Arcury and Quandt 2011). Most agricultural workers in North Carolina are unauthorized and are in persistent threat of deportation. The living and working circumstances of these workers are much more chaotic and unstable, characterized by a higher degree of mobility and a broader range of living situations, than those of H-2A workers. Providers stated that conditions for unauthorized agricultural workers are substantially worse than those faced by H-2A workers due to a lack of regulatory protections and engagement with unscrupulous labor contractors or crew leaders (cf. Hubner 2000), who recruit mainly young, single, and unauthorized Latino men from states like Texas, Florida and Georgia to work in North Carolina or other states. They also indicated that crew leaders exercise considerable control over farm workers’ lives, often providing housing, transportation and food to workers at inflated prices (cf. Smith-Nonini 2005). Unauthorized agricultural workers were reported to experience more mobility than H-2A workers because they have few legal protections and many are under the control of crew leaders; as a result, these men were described as fearful and likely to change jobs or living arrangements if they feel threatened. A nurse and a rural health clinic coordinator emphasized, “When you add fear to their life, it beats them down.” For these men, mobility was said to reduce access to health care and also increase their contact with a wider array of sex work services and potentially overlapping sexual networks.

Providers also described large numbers of unauthorized men in non-agricultural work such as construction, landscaping, painting and other kinds of short-term labor. They indicated that while these men may be socially hidden due to their unauthorized status, they are not as geographically isolated in rural areas as farm workers. They often reside in peri-urban and urban trailer parks, apartment complexes and residential situations where there are large numbers of men without female partners, and where, as a consequence, they come into contact with a variety of sex work services.

Mobility among sex workers

Within the four-county area, sex work services are available in a diverse array of settings and venues, including streets, brothels, camps, and residential settings. Providers noted that sex work in the area is characterized not only by venue and demographics of the women providing services, but by differences in the organizational structure of sex work and the patterns of mobility associated with these structures.

Our work was prompted in part by anecdotal reports of “mobile brothels” and “mobile sex workers” operating in areas with large Latino male populations (cf. Vissman et al. 2009). Brothels are heterogeneous and are likely products of large criminal networks (Polaris Project 2009). They are also rudimentary and transient structures, setting up operations in trailers, houses or apartments in residential areas, and then moving location or disappearing entirely to evade law enforcement. A legal services provider who had accompanied police on a raid described the house as “barebones,” with only a washing machine, couches, a television and mattresses on the floor. Polaris Project, an anti-trafficking organization, reported that brothels are usually set up in residential areas and housed in low-cost, low value properties, in an effort to remain portable and flexible (Polaris Project 2009). Outside of Siler City, for example, we saw two abandoned house trailers that had recently functioned as brothels servicing Latino men. An outreach worker explained that when a raid had closed one trailer, operations had moved up the road to the other, but recently they had both closed due to pressure from law enforcement.

The scope of brothel networks is unknown but there is indication that some networks are extensive and well-organized, with “regional or multi-state breadth with multiple coordinated brothel locations, centralized ownership, and regional transporters to drive women to different brothels” (Polaris Project 2009:8). Most providers perceived the brothels as being part of different networks and possibly linked to Mexican drug cartels. Groups of women, described as primarily from the Dominican Republic, Mexico and Central America, and Puerto Rico reportedly rotate on a weekly or bi-weekly basis across a large region that extends from New York to Florida along the Eastern corridor; this pattern has also been documented by Polaris Project (2009). Many of these women are likely unauthorized and vulnerable due to economic or other factors; and some have been trafficked.

Brothel sex workers were reported to be patronized primarily by Latino men who live in peri-urban and urban areas, most of whom are not farm workers. Sex workers see from 15–20 clients a day, usually in 15-minute increments, with clients paying $20–30 for vaginal sex. An outreach worker who had worked as brothel security reported that the fee for sex is usually split between the sex worker and the brothel owner, with earnings collected by the owner on a weekly basis. Providers indicated that there may be owners, transporters, doorman, and look-outs who share in the earnings, depending on the size and complexity of the brothel network. Given the large volume of clients serviced per day, and the low overhead, brothels can be lucrative operations (Polaris Project 2009).

Providers recounted that sex workers were transported across a broad geographic region to migrant camps in rural areas, although it is not entirely clear if these women are part of the same networks as brothel-based sex workers. Providers in public health and outreach organizations described seeing “phantom sex vans,” usually unmarked white vehicles, arriving at migrant camps with small groups of women, usually in the evenings or on weekends. They reported that most women appeared to be young and Hispanic, although they also occasionally encountered Caribbean and African-American women. Women are usually accompanied by a pimp or “padrote,” who waits while the women provide sex to farm workers. Providers thought that these women, too, travel extensively throughout the region, staying a week or two in one location, and said that the frequency of sex worker visits to migrant camps had increased over the past several years. Similar to brothel workers, large numbers of clients are serviced at 15-minute intervals for around $30; camps can hold up to 80–100 men. “When the vans come,” a public health nurse told us, “the women spread out into different rooms in the camps and the men who are interested go to one of the rooms.” She added that the men deny having knowledge of sex workers but they also report needing condoms during routine health assessments: “If you dig for information, the men will disclose. If one guy has something and it’s known he used a sex worker and other guys have used a sex worker too, they will ask about symptoms and talk about sex work.”

Highly mobile sex workers were also reported to target Latino men in residential areas, traveling into a city to provide services for a few months, and then presumably returning to their home location. For example, outreach workers noted an influx of Dominican, Mexican and Central American women traveling into the Raleigh area from New York. These women may take up temporary residence in an apartment complex where there are large numbers of Latino men, and sometimes go door to door soliciting clients. Women also travel to the area looking for work in local bars and cantinas (bars); while our assessment did not detect a systematic pattern of sex work services being provided through local cantinas, this pattern has been reported elsewhere (Polaris Project 2009; Rhodes et al. 2012).

The patterns described above are characterized by a high degree of mobility, with sex workers often traveling routinely throughout an extensive geographic region to serve large numbers of Latino clients. While it is clear that many of these highly mobile sex workers reside outside these counties, local women also target Latino men. These women appear to be fewer in number and not associated with any organizational structure; they may work autonomously and sporadically as the need arises, although some may have male partners who help them procure clients. When we accompanied a male outreach worker conducting door-to-door activities in a Raleigh apartment complex, Latina residents indicated that individual African-American, Caucasian American, and Latina women all frequented the complex, and would often have sex with men in a wooded area behind the complex.

Providers described street-based sex workers, mostly in Raleigh, also as local women who have migrant Latino men as clients. Relatively small numbers of predominantly African-American women can be found in predictable locations on streets near abandoned or condemned houses. Providers working with this population described them as women with a long history of physical, emotional and sexual trauma, and suffering from substance abuse, mental health issues, and unstable housing situations. These women were reported have a diverse client base that includes migrant Latino men but they see far fewer clients than most women who provide services to Latino men, usually only 2–3 clients a day. Interviews carried out by an HIV/AIDS health educator in Raleigh revealed that Latino men who were arrested were soliciting street-based sex workers because they were lonely, did not know other ways to meet women, and were encouraged by others to lose their virginity to sex workers (Raleigh Police Department 2006).

PUBLIC HEALTH AND MOBILE POPULATIONS IN NORTH CAROLINA

Unauthorized immigration and sex work are hidden, criminalized, and highly stigmatized activities, which makes reaching persons involved in them with health and other services challenging. Even under the best of situations, it takes time to establish trust and credibility and to overcome barriers created by gatekeepers such as crew leaders and pimps, time that may be protracted under conditions of high mobility and turnover in the population. At the same time, participation in these activities and the high degree of mobility associated with them necessarily increases the need to intervene with services that protect health.

Among those we interviewed, there is great concern about the challenges of reaching mobile sex workers and migrant Latino men and the need for structural interventions to address issues of access to care and social marginalization. Although providers advocated for increasing programs for migrant Latino men including those which provide condoms and skills-based demonstrations during clinics and outreach activities, they also acknowledged that the few available services were reaching, as one provider regretfully said, “low hanging fruit.” The bulk of services available to migrant men appear to be addressed toward men who hold H-2A visas; yet these men are much less mobile as compared to unauthorized men who move frequently and come in contact with multiple groups of sex workers and multiple sexual networks. An outreach worker described his interactions with unauthorized workers as difficult saying, “Trust is a big issue. They won’t talk to you, even when they are a case or named as a contact. They think we are going to report them for being undocumented.” Providers said that far more services need to be available for men who live in urban areas because these men also experience a high degree of mobility and encounter sex workers in a wide variety of venues, including brothels, streets, cantinas and through door to door solicitation.

Providers also expressed concern for the limited or lack of health and social services for all sex workers, despite the alarming conditions in which many sex workers live and work. Permanent and transitional housing and temporary shelter, along with delivery of mobile health and social services focused on peer mentors, condom provision and mental health and substance abuse treatment were identified as critical needs for women in this population (cf. Thukral and Ditmore 2003). One provider stated, “You need to be able to find a place for women to go where they feel safe.”

The main challenge for providers in working with mobile sex workers is making contact. Lack of knowledge regarding when and where sex workers are working as well as the high degree of mobility among them and the presence of male controllers make it difficult to predict when to provide services and communicate with sex workers. A participant reflected, “It’s mobile, we can never pin it down to provide the ladies with information and condoms. All we can do is give information and condoms to the farm workers.” Providers were aware that attempts to reach sex workers with interventions would require establishing rapport and trust with controllers and pimps, an approach that has been successful in many other settings, but which will require time and additional resources.

Providers called for clearer policies and programmatic efforts to reach sex workers with intervention, saying that current efforts to engage with sex workers are sporadic and not actively encouraged. A public health nurse had the perception that her superiors were reluctant to engage with sex workers for fear of appearing to condone participation in illegal activity. She said, “Right now, we are counting on the goodness of the pimp to bring [the sex worker] in—it is clear though that we don’t really engage them enough.”

MOBILITY AS AN ORGANIZING PUBLIC HEALTH PRINCIPLE

Our research underscores that REA can be a useful approach for better understanding the complex relations between unauthorized migrant labor, mobility, and structural and social vulnerability. By incorporating ethnographic methods into public health needs assessments, we were able to 1) shed light on the diversity of migrant experiences within the US Southeast and 2) contribute to a better understanding of mobility patterns among sex workers and migrant men, and 3) identify key structural barriers affecting the delivery of health care to these populations.

In the field of public health, issues related to migration and mobility are often inadequately understood because traditional methods of public health inquiry (i.e. surveys, clinical trials) rely on random sampling methods, standardized definitions of study populations, and usually involve populations that have lower likelihoods of being lost to follow up, all of which help facilitate population-based estimates of health issues. Highly mobile populations, in contrast, are difficult to access, recruit, and retain in many public health studies; hence, the dynamics of disease prevention and transmission may be less well-understood.

More effort needs to be made to understand mobility as an organizing principle in public health research and practice, not only among Latino migrant workers, but among other vulnerable populations who experience mobility (e.g. homelessness, unstable housing). Migration and mobility patterns are far more complex and heterogeneous than are commonly recognized in public health practice, with many migrants experiencing cyclical, seasonal or peripatetic mobility over time and for a variety of factors based on economic opportunity, social ties, war, and displacement. More research, especially research that incorporates ethnographic methods, is needed to better understand the persistent shifting context of mobility in the United States and its implications for public health and delivery of health care services.

Currently, few existing models of public health delivery, especially in the context of HIV/STD, are designed to provide health care to mobile, unauthorized, and ethnically diverse populations involving mobile outreach, patient navigation systems, community health workers, alternative operating hours, and low literacy health education. Notable exceptions such as the Salud Mobile Outreach Program, a mobile clinic that travels to sites heavily accessed by migrants in Colorado, and MiVia, a patient electronic personal health record originally designed for migrant and seasonal farm workers and later expanded to include other mobile populations such as the homeless, can serve as models. The European Network for HIV/STI Prevention and Health Promotion among Migrant Sex Workers, an international networking and intervention program operating in 25 countries, provides another useful model for replication in the United States.

Community and migrant health centers and community based organizations are able to reach only a fraction of those who are mobile. A vast majority have no access or seek irregular health care services in emergency rooms or free clinics “that often are not prepared to provide the scope and quality of services so badly needed by the mobile poor (e.g., transportation, interpretation, financial assistance, preventive services, as well as clinical care)” (Kugel and Zuroweste 2010:425). Mobility also restricts the continuity of care in this model, with very little opportunity to complete treatments, access medical records, and obtain routine or preventive care (Josiah, Núñez, and Talavera 2009). In addition to mobility, low-wage jobs without benefits, dangerous and debilitating working conditions, lack of health insurance, social isolation, fear of deportation, and immigration policies restrict access to health services and prevent many mobile populations from seeking services. These issues create severe barriers to health care and drive poor health outcomes.

CONCLUSION

High mobility is not limited to Latino farmworkers and sex workers, but is experienced by broader groups of the working poor, including those who are unstably housed, the homeless, and unauthorized migrants (Kugel and Zuroweste 2010). The transient and provisional social and physical environments of those who are highly mobile heavily impact their health outcomes. Structural barriers to health care access and delivery for highly mobile populations in the United States, especially those considered “illegal” or “unauthorized,” include immigration and citizenship status, unstable housing, language and transportation barriers, low paying and unstable jobs, lack of insurance and knowledge about health services, and substance abuse and mental health issues (Chavez 1985; Leibow 1995; Newman 2000; Hopper 2002; Shipler 2005; Arcury and Quandt 2007; Kochhar, Suro, and Tafoya 2009). There exists a violent cycle between poor health and marginalized status for highly mobile populations: their health is directly linked to their social, economic, and political integration, and poor health exacerbates their social, economic, and political marginalization (Castro and Singer 2004; Quesada et al. 2011; Sargent and Larchanche 2011; Chavez 2012; Holmes 2012; Quesada 2012; Willen 2012). More work needs to address the broader health implications of the migratory experience and mobility itself, along with issues related to structural determinants of migrant health and social suffering of mobile populations. Public health can benefit by incorporating the concept of mobility as an organizing principle for the delivery of services to large segments of the population and developing policy and program models to address the needs of mobile populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Rachel Robitz and Petra Vallila-Buchman for being part of the original rapid assessment field team, and Pete Moore and Jacquelyn Clymore of the North Carolina HIV/STD Prevention and Care Branch for their assistance in planning for the assessment.

Biographies

THURKA SANGARAMOORTHY, PhD, MPH, is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland, USA. She is a medical anthropologist whose research focuses on the medical, epidemiological, and social constructions of HIV/AIDS risk, and the naturalization of health disparities within biomedicine and public health. For more than 10 years, she has worked in the fields of sexual health and STD/HIV prevention in a wide variety of global and domestic institutions.

KAREN KROEGER, PhD, is a Research Anthropologist with the Division of STD Prevention at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, USA. She has over 15 years of experience in conducting applied ethnographic research, including large and small-scale rapid assessments, among vulnerable populations in the US, Africa, and Asia. She has presented on rapid assessment findings at national and international conferences and has conducted trainings and workshops on rapid assessment in a variety of settings, including the University of New Mexico, Jackson State University, and in South Africa, Mozambique, and Ethiopia.

References

- Abrams LS. Sampling “Hard to Reach” Populations in Qualitative Research: The Case of Incarcerated Youth. Qualitative Social Work. 2010;9(4):536–550. [Google Scholar]

- Agar M. An Ethnography By Any Other Name …. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2006;7(4) [Google Scholar]

- Anker M, Guidotti R, Orzeszyna S, Sapirie S, Thuriax M. Rapid evaluation methods (REM) of health services performance: Methodological observations. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1993;71(1):15–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostolopoulos Y, Sonmez S, Kronenfeld J, Castillo E, McLendon L, Smith D. STI/HIV risks for Mexican migrant laborers: Exploratory ethnographies. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2006;8:291–302. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9334-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aral SO, St Lawrence JS. The ecology of sex work and drug use in Saratov Oblast, Russia. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29(12):798–805. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200212000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aral SO, St Lawrence JS, Dyatlov R, Kozlov A. Commercial sex work, drug use, and sexually transmitted infections in St. Petersburg, Russia. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;60:2181–2190. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcury TA, Quandt SA. Delivery of health services to migrant and seasonal farmworkers. Annual Review of Public Health. 2007;28:345–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcury TA, Quandt SA. Living and Working Safely: Challenges for Migrant and Seasonal Farmworkers. North Carolina Medical Journal. 2011;72(6):466–470. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe J. Rapid assessment process: An introduction. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley ME, Pelto GH, Straus WL, Schumann DA, Adegbola C, de la Pena E, Oni GA, Brown KH, Huffman SL. Rapid ethnographic assessment: Applications in a diarrhea management program. Social Science and Medicine. 1988;27(1):107–116. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90168-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bletzer K. Risk and danger among women-who-prostitute in areas where farmworkers predominate. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2003;17:251–278. doi: 10.1525/maq.2003.17.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunstein MS. Sampling a Hidden Population: Noninstitutionalized Drug Users AIDS. Education and Prevention. 1993;5(2):131–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda H. Im/migration and Health: Conceptual, Methodological, and Theoretical Propositions for Applied Anthropology. Annals of Applied Anthropology. 2010;34(1):6–27. [Google Scholar]

- Castro A, Singer M, editors. Unhealthy Health Policy: A Critical Anthropological Examination. Walnut Creek: Altamira Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Estimated lifetime risk for diagnosis of HIV infection among Hispanics/Latinos—37 states and Puerto Rico, 2007. MMWR. 2010a;59(40):1297–1301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2009 2010b [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R. The origins and practice of participatory rural appraisal. World Development. 1994a;22(7):953–969. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R. Participatory rural appraisal (PRA): Challenges, potentials and paradigm. World Development. 1994b;22(10):1473–1454. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez LR, Cornelius WA, Jones OW. Mexican immigrants and the utilization of health services: the case of San Diego. Social Science and Medicine. 1985;20:93–102. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(85)90291-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez LR. Undocumented immigrants and their use of medical services in Orange County, California. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74:887–893. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd. CA: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Del Rio C. Latinos and HIV care in the southeastern United States: new challenges complicating longstanding problems. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2011;53(5):488–489. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis A, Napravnik S, Seña A, Eron J. Late Entry to HIV Care Among Latinos Compared With Non-Latinos in a Southeastern US Cohort. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2011;53(5):480–487. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis SR, Ríos-Vargas M, Nora G. 2010 Census Briefs. The Hispanic Population. 2010 Accessed at: http://2010.census.gov/2010census/data/

- Handwerker WP. Quick Ethnography. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Harris KJ, Jerome NW, Fawcett SB. Rapid Assessment Procedures: A review and critique. Human Organization. 1997;56:375–378. [Google Scholar]

- Josiah MH, Núñez GG, Talavera V. Health Care Access and Barriers for Unauthorized Immigrants in El Paso County, Texas. Family and Community Health. 2009;32(1):4–21. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000342813.42025.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand PE. Rapid Rural Appraisal Conference. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex; 1979. Summary of the sondeo methodology used by ICTA. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes SM. An Ethnographic Study of the Social Context of Migrant Health in the United States. Public Library of Science Medicine. 2006;3(10):e448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes SM. Structural Vulnerability and Hierarchies of Ethnicity and Citizenship on the Farm. Medical Anthropology. 2011;30(4):425–49. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2011.576728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes SM. The Clinical Gaze in the Practice of Migrant Health: A Qualitative Study of Interactions and Barriers Between Medical Professionals and Unauthorized Mexican Migrants in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74(6):873–881. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper K. Reckoning with Homelessness. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hubner J. Farm Workers Face Hard Times; Middlemen Maximize Profits by Paying as Little as Possible. San Jose Mercury News. 2000 Jul 7; [Google Scholar]

- Hudelson PM. Qualitative Research for Health Programmes No WHO/MNH/PSF/94.3 Rev 1. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kissinger P, Kovacs S, Anderson-Smits C, Schmidt N, Salinas O, Hembling J, Beaulieu A, Longfellow L, Liddon N, Rice J, Shedlin M. Patterns and Predictors of HIV/STI Risk Among Latino Migrant Men in a New Receiving Community. Aids and Behavior. 2012;16(1):199–213. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9945-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knipper E, Rhodes SD, Lindstrom K, Bloom FR, Leichliter JS, Montaño J. Condom use among heterosexual immigrant Latino men in the Southeastern United States. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2007;19:436–447. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.5.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Proximal, distal, and the politics of causation. What’s level got to do with it? American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:221–230. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.111278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochhar R, Suro R, Tafoya Sonya. The New Latino South: the context and consequences of rapid population growth Report. Washington, D.C: Pew Hispanic Center; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kugel C, Zuroweste EL. The state of health care services for mobile poor populations: history, current status, and future challenges. Journal of Health Care of the Poor and Underserved. 2010;21(2):421–429. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latino Commission on AIDS. The crisis of HIV/AIDS among Latinos/Hispanics in US. Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Leibow E. Tell Them Who I Am: The Lives of Homeless Women. New York: Penguin; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Manderson L, Aaby P. An Epidemic in the Field? Rapid Assessment Procedures and Health Research. Social Science and Medicine. 1992;35(7):839–850. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90098-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M, Wilkinson R, editors. Social Determinants of Health. New York: Oxford; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mays N, Pope C, editors. Qualitative Research in Health Care. 2. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- NC Farmworker Health Program. Farmworker focus group results: Sexually transmitted infections and the use of prostitutes among Latino farmworkers. 2000 Retrieved from http://ncfhp.org/pdf/aliciastds.pdf.

- Navarro V, editor. The Political and Social Contexts of Health. Amityville, NY: Baywood; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Needle RH, Trotter RT, Goosby E, Bates C, Von Zinkernagel D. Methodologically sound rapid assessment and response: providing timely data for policy development on drug use interventions and HIV prevention. The International Journal of Drug Policy. 2000;11:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Needle RH, Trotter RT, Singer M, Bates C, Page JB, Metzger D, Marcelin LH. Rapid assessment of the HIV/AIDS crisis in racial and ethnic minority communities: An approach for timely community interventions. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(6):970–979. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needle RH, Kroeger K, Belani H, Achrekar A, Parry CD, Dewing S. Sex, drugs, and HIV: Rapid assessment of HIV risk behaviors among street-based drug using sex workers in Durban, South Africa. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;67:1447–1455. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman K. No Shame in My Game: The Working Poor in the Inner City. New York: Vintage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Organista KC, Carrillo H, Ayala G. HIV prevention with Mexican migrants. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;37(4):S227–S239. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000141250.08475.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter T. Connecting the dots: When the risks of HIV/STD infection appear high but the burden of infection is not known—the case of the male Latino migrants in the Southern United States. AIDS Behavior. 2008;12:213–226. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrado EA, Flippen C. Community attachment, neighborhood context, and sex worker use among Hispanic migrants in Durham, North Carolina, USA. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;70:1059–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrado EA, Flippen C, McQuiston C. Use of commercial sex workers among Hispanic migrants in North Carolina: Implications for spread of HIV. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;36:150–156. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.150.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry CD, Dewing S, Petersen P, Carney T, Needle R, Kroeger K, Treger L. Rapid assessment of HIV risk behavior in drug using sex workers in three cities in South Africa. AIDS Behavior. 2009;13(5):849–859. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9367-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passel JS, Cohn D, Lopez MH. Census 2010: 50 Million Latinos Hispanics Account for More than Half of Nation’s Growth in Past Decade. Pew Hispanic Center; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Paz-Bailey G, Teran S, Kevine W, Markowitz L. Syphilis outbreak among Hispanic immigrants in Decatur, Alabama. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2004;31:20–25. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000104813.21860.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polaris Project. Latino Residential Brothels and Related Sex Trafficking Networks At-a-Glance. Washington, DC: The Polaris Project; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Izazola-Licea J, Gortmaker S. Extrarelational sex among Mexican men and their partners’ risk of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1650–1652. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.10.1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesada J, Hart LK, Bourgois P. Structural vulnerability and health: Latino migrant laborers in the United States. Medical Anthropology. 2011;30:339–362. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2011.576725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesada J. “Illegalization” and embodied vulnerability. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74:894–896. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raleigh Police Department. Operation dragnet: Reducing the visibility of street prostitution in Raleigh, NC. Raleigh, NC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes S, Bischoff W, Burnell J, Whalley L, Walkup M, Vallejos Q, Arcury T. HIV and sexually transmitted disease risk among male Hispanic/Latino migrant farmworkers in the Southeast: findings from a pilot CBPR study. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2010;53(10):976–983. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes S, Tanner A, Duck S, Aronson RE, Alonzo J, Garcia M, Wilkin AM, Cashman R, Vissman AT, Miller C, Kroeger K, Naughton MJ. Female Sex Work Within the Rural Immigrant Latino Community in the Southeast United States: An Exploratory Qualitative Community-Based Participatory Research Study. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. 2012;6(4):417–427. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent C, Larchanché S. Transnational migration and global health: the production and management of risk, illness, and access to care. Annual Review of Anthropology. 2011;40:345–361. [Google Scholar]

- Scrimshaw S, Hurtado E. Rapid assessment procedures for nutrition and primary health care: Anthropological approaches to improving programme effectiveness. Tokyo, Japan: United Nations University; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Seña A, Hammer J, Wilson K, Zeveloff A, Gamble J. Feasibility and acceptability of door-to-door rapid HIV testing among Latino immigrant and their HIV risk factors in North Carolina. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2010;24:165–173. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipler DK. The Working Poor: Invisible in America. New York: Vintage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M. Studying Hidden and Hard-to-Research Populations. In: Schensul J, LeCompte Md, Trotter R, Cromley E, Singer M, editors. The Ethnographer’s Toolkit. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press; 1999. pp. 164–241. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Nonini S. In: Federally-sponsored Mexican Migrants in the Transnational South Chapter in The American South in a Global World. Peacock James L, Watson Harry L, Matthews Carrie R., editors. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sterk CE. Fast lives: Women who use crack cocaine. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Thukral J, Ditmore M. Revolving Door: An Analysis of Street-Based Prostitution in New York City. New York: Urban Justice Center, Sex Workers Project; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Trotter R, Needle R, Goosby E, Bates C, Singer M. A methodological model for rapid assessment, response, and evaluation: the RARE program in public health. Field Methods. 2001;13:137–159. [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. North Carolina state & county quickfacts. 2009 Retrieved from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/37000.html.

- Viadro C, Earp JA. The sexual behavior of married Mexican immigrant men in North Carolina. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;50:723–735. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00305-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissman A, Eng E, Aronson R, Bloom F, Leichliter J, Montaño J, Rhodes S. What do men who serve as lay health advisors really do? Immigrant Latino men share their experience as Navegantes to prevent HIV. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2009;21:220–232. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wholey J. Evaluation and effective public management. Boston: Little, Brown; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Willen SS, Mulligan J, Castañeda H. Take a stand commentary: how can medical anthropologists contribute to contemporary conversations on “illegal” im/migration and health? Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2011;45:331–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1387.2011.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willen SS. Introduction to the Special Issue: Migration, “Illegality,” and Health: Mapping Embodied Vulnerability and Debating Health-Related Deservingness. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74(6):805–811. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]