In traditional agroecosystems, provision of ecosystem services is driven by interrelated, place-based, social-ecological properties.

Abstract

Wood-pastures are complex social-ecological systems (SES), which are the product of long-term interaction between society and its surrounding landscape. Traditionally characterized by multifunctional low-intensity management that enhanced a wide range of ecosystem services (ES), current farm management has shifted toward more intensive farm models. This study assesses the supply of ES in four study areas dominated by managed wood-pastures in Spain, Sweden, and Romania. On the basis of 144 farm surveys and the use of multivariate techniques, we characterize farm management and structure in the study areas and identify the trade-offs in ES supply associated with this management. We link these trade-offs to multiple factors that characterize the landholding: economic, social, environmental, technological, and governance. Finally, we analyze how landholders’ values and perspectives have an effect on management decisions. Results show a differentiated pattern of ES supply in the four study areas. We identified four types of trade-offs in ES supply that appear depending on what is being promoted by the farm management and that are associated with different dimensions of wood-pasture management: productivity-related trade-offs, crop production–related trade-offs, multifunctionality-related trade-offs, and farm accessibility–related trade-offs. These trade-offs are influenced by complex interactions between the properties of the SES, which have a direct influence on landholders’ perspectives and motivations. The findings of this paper advance the understanding of the dynamics between agroecosystems and society and can inform system-based agricultural and conservation policies.

INTRODUCTION

European wood-pastures are considered archetypes of multifunctional landscapes and high nature value farming systems due to the high natural and cultural values they contain (1) and the multiple ecosystem services (ES) they provide (2, 3). Developed as tightly coupled social-ecological systems (SES) (4), wood-pastures constitute a significant part of European cultural and natural heritage (5). Their physiognomy varies across Europe, but commonly shared features include the existence of trees at various densities across a landscape managed mostly for livestock grazing (6). Wood-pasture management is traditionally multifunctional, combining animal production with small-scale cereal production (mostly to produce animal fodder), the extraction of forest products (for example, fruit, firewood, and cork), and the provision of habitat for game hunting and recreational activities (7). Despite their substantial current extent (covering ca. 4.7% of Europe’s surface), the area of wood-pastures is shrinking and they are relict or have disappeared in many regions of Europe (2, 8). Remaining wood-pastures are facing multiple and accelerated environmental, socioeconomic, and political changes. The loss of traditional multifunctional management typically leads to a simplification and/or loss of these landscapes in an antagonistic parallel process of management intensification and land-use abandonment (9).

The causes behind these dynamics are complex and interrelated. From the perspective of economic efficiency, the low direct productivity of these traditional systems compared to intensive animal production systems makes wood-pastures less competitive in a delocalized market, where farmland management efficiency is valued exclusively by the yields harvested (10). From the perspective of policy, the heterogeneous character of wood-pastures is difficult to integrate within the current policies governing commodity production landscapes (for example, agricultural and forestry) (11). From a sociodemographic perspective, wood-pastures are highly vulnerable to land abandonment caused by shrinking human population sizes in rural areas, which leads to a lack of generational replacement and loss of traditional local knowledge (12).

The ES framework has proved useful in understanding human-nature relationships in SES. ES are jointly produced through the interaction between the ecological and social subsystems of the SES in wood-pastures (13, 14). In Europe, multiple studies have assessed the supply of ES in wood-pastures from various perspectives, including biophysical (8, 15), sociocultural (16, 17), and economic valuations (18, 19). This accumulated knowledge demonstrates the importance of management in the maintenance of wood-pastures, because shifts in management may lead to changes in the provision of multiple ES that rely on the same ecosystem process or are affected by the same external factor. For example, an increase in grazing pressure might enhance animal production but may, in turn, reduce the potential for harvesting wild resources. These positive or negative covariations in the supply of multiple ES are known as synergies and trade-offs. Trade-offs are rather complex, behave in diverse ways at different spatial and temporal scales (20, 21), and are affected by both sociocultural and environmental factors (22, 23). In European agroecosystems, ES trade-offs have been assessed on multiple occasions, with trade-offs being repeatedly identified between provisioning services on the one side and regulating and cultural service categories on the other (24, 25). When a set of ES appears together consistently, it is referred to as a bundle of ES (26). Identifying these bundles has been receiving increased attention as they can potentially give a powerful message to managers and policy makers when working with complex landscapes (27–29). However, the current focus in ES trade-off analysis and bundle identification is mainly on the differences between land-use types, whereas little attention has been given to the mechanisms by which trade-offs and bundles appear within these land uses under different conditions (30). In traditional agricultural landscapes, typically characterized by their multifunctionality, the identification of these linkages is of high relevance because farm management decisions will foster the provision of specific bundles of ES at the expense of others, establishing trade-offs that are associated with different dimensions of farm management (26).

Despite the increased interest in ES trade-offs, little attention has been paid to the underlying environmental and socioeconomic properties of SES that affect both the supply and demand of ES [but see the study of Burton and Schwarz (31)]. In agroecosystems, landowners and/or managers have a central role to play as ultimate decision makers regarding the management strategy and thus the regulation of the provision of ES. Their values, future perspectives, and decisions will be directly influenced by diverse context-based social-ecological conditions, primarily of economic character (31, 32), although sociocultural considerations often play an almost equally important role (33, 34). Understanding the linkages between the properties of SES, farmers’ attitudes, and their effect on the supply of ES can substantially contribute to design and promote system-based policies that address the complex and specific nature of SES.

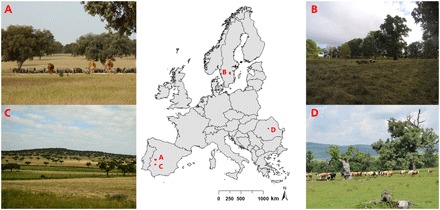

The overarching goal of our research is to illustrate how the SES framework (35) can be articulated to understand the supply of ES in agroecosystems to contribute to context-based policies for landscape planning and management. We hypothesize that in European wood-pastures, ES supply will be driven by multiple dimensions of management, establishing clearly defined trade-offs that will go beyond the classic gradient of intensity in management (hypothesis 1). The specific outcomes of these trade-offs will be driven by diverse and context-based social-ecological properties affecting landowners’ values and perspectives (hypothesis 2). Therefore, in each region, the same land use would display a different pattern of ES provision because it will be playing a different role in the SES, which mirrors local needs and demands (hypothesis 3). To address the above hypotheses, the present paper follows existing methodological guidelines (36) to assess and interrelate ES supply, ES trade-offs, SES properties, and farmers’ perceived values and threats across four distinct oak wood-pasture–dominated regions in Europe that differ culturally, environmentally, and socioeconomically (Llanos de Trujillo in Spain, Östergötland in Sweden, La Serena in Spain, and the Saxon cultural region of southern Transylvania in Romania; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Study areas with representative pictures of the oak wood-pastures.

(A) Llanos de Trujillo. (B) Östergötland. (C) La Serena. (D) Southern Transylvania.

To assess the supply of ES in each wood-pasture, we used an integrated social-ecological approach that incorporates—based on interviews with landholders—indicators for provisioning, regulating, and cultural ES categories and allows the identification of ES trade-offs and synergies. To evaluate the interrelation between these trade-offs and the SES properties, we considered multiple factors for each wood-pasture, accounting for biophysical, social, governance, technological, and economic characteristics. Finally, to assess how all the abovementioned elements influence landholders’ attitudes to wood-pasture management, we evaluated how landholders consider the contribution of wood-pastures to their quality of life and which threats they think are relevant to their current management.

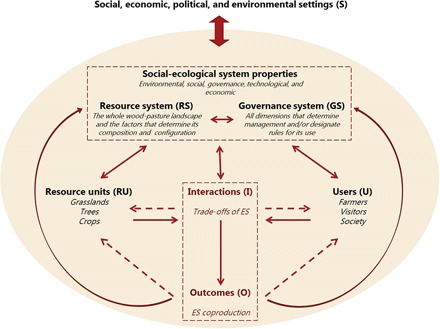

In Fig. 2, we adapt Ostrom’s SES framework (35) to conceptualize the supply of ES in wood-pastures. Taking a specific wood-pasture, the coproduction of ES (14) (outcomes, O) would be determined by the interaction (I) between the resource system (RS), the governance system (GS), the resource units (RU), and the users (U). RS encompasses the wood-pasture landscape, including all the factors and processes that maintain its composition and structure. GS includes all the processes and factors that, to a certain extent, determine the management of wood-pastures and regulate their use. Together, RS and GS outline the biophysical, social, governance, technological, and economic properties of the SES. Some of these system properties have a direct effect on ES supply (for example, soil fertility has a direct positive effect on cereal production; a ban on game hunting during the mating season has a direct negative effect on the harvesting of wild products), whereas others have an indirect effect (for example, dense vegetation indirectly increases recreational game hunting activities by improving wildlife habitat, whereas its suitability for hiking deteriorates). RU is composed of all the land uses and landscape features present in the wood-pasture, and U includes not only all those benefiting directly from wood-pastures either productively (such as farmers) or through nonmaterial means (visitors and tourists) but also those benefiting indirectly (consumers of high-quality meat products). All these elements are embedded within larger environmental, economic, political, and social settings (S).

Fig. 2. Framework for analyzing the coproduction of ES in wood-pastures as SES.

Solid line arrows indicate a direct relationship, and dashed arrows indicate an indirect relationship.

RESULTS

Ecosystem service supply

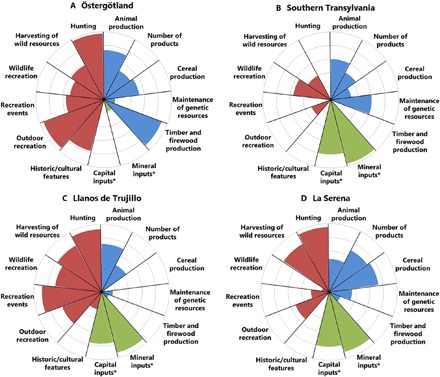

On the basis of 13 ES indicators used over a total of 144 wood-pasture–dominated landholdings (see Materials and Methods for a detailed account of the semistructured interview protocol and addressed indicators), the comparison of the four study areas showed distinct patterns of ES supply for each study area (Fig. 3). Wood-pastures in Östergötland (Fig. 3A) revealed the highest values for provisioning ES such as animal and timber production and for cultural ES such as outdoor recreation, historic and cultural values, and hunting. We used the amount of mineral and capital inputs as inverse indicators of regulating ES, which revealed that Swedish wood-pastures showed the lowest values for regulating ES among the four study areas. In contrast, wood-pastures in southern Transylvania (Fig. 3B) displayed the lowest values for firewood production, as well as for outdoor recreation, recreation events, harvesting of wild resources, historic and cultural values, and hunting. On the other hand, they showed the highest values for regulating ES and the highest values for maintenance of genetic resources (in terms of animal breeds). Landholdings in Llanos de Trujillo (Fig. 3C) showed the highest values for the cultural ES of wildlife recreation and recreation events and the lowest values for the provisioning service of cereal production. Finally, wood-pastures in La Serena (Fig. 3D) had the highest values for the number of products and cereal production and for cultural ES such as the harvesting of wild resources and the lowest values for animal production and cultural ES such as wildlife recreation and historic and cultural values.

Fig. 3. Flower diagrams for the four study areas.

The blue color indicates provisioning services, green denotes regulating services, and red refers to cultural ES. *Values for the indicators of ecosystem mineral inputs and capital inputs were inverted for interpretative reasons.

Trade-offs of ES

We identified four types of ES trade-offs by comparing the indicators of ES supply among the 144 landholdings. The projection of the ES indicators in the principal components analysis (PCA) for mixed data reduced the variability in ES supply to four components, which absorbed 65.39% of the variability and had an eigenvalue larger than 1 (Table 1).

Table 1. Factor loadings derived from the PCA for mixed data.

For each variable, values in bold correspond to the factor for which the squared cosine is the largest.

|

F1 Productivity-related trade-offs |

F2 Crop production–related trade-offs |

F3 Multifunctionality-related trade-offs |

F4 Farm accessibility–related trade-offs |

|

| Active variables | ||||

| Animal production | 0.22 | 0.12 | -0.66 | 0.05 |

| Number of products | 0.20 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.11 |

| Cereal production | −0.01 | 0.77 | 0.04 | 0.18 |

| Maintenance of genetic resources | −0.55 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.36 |

| Timber and firewood production | 0.70 | 0.25 | 0.30 | −0.20 |

| Mineral inputs | −0.18 | −0.52 | 0.26 | −0.14 |

| Capital inputs | −0.49 | −0.39 | 0.65 | −0.02 |

| Historic and cultural features | 1.06 | 0.11 | −0.05 | 0.65 |

| Outdoor recreation | 0.55 | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.38 |

| Recreational events | 0.75 | −0.49 | 0.07 | −0.05 |

| Wildlife-related recreation | 0.08 | −0.53 | 0.04 | 0.68 |

| Harvesting of wild resources | 0.34 | 0.02 | 0.20 | −0.11 |

| Hunting | 0.65 | −0.07 | 0.11 | −0.20 |

| Study areas | ||||

| Östergötland | 1.01 | 0.54 | −0.26 | 0.33 |

| Southern Transylvania | −1.20 | 0.20 | −0.07 | 0.43 |

| Llanos de Trujillo | 0.44 | −1.04 | 0.13 | −0.40 |

| La Serena | 0.09 | 0.77 | 0.96 | −0.79 |

| Eigenvalue | 3.47 | 2.04 | 1.55 | 1.20 |

| Variance explained (%) | 29.92 | 15.98 | 10.71 | 9.34 |

| Cumulative variance (%) | 29.92 | 45.91 | 56.62 | 65.95 |

The positive side of the first axis, identified as productivity-related trade-offs, was associated on the positive side with provisioning ES, such as timber and firewood production, and with cultural ES such as historical and cultural values, outdoor recreation, social events, hunting, and wild resources harvesting. On the negative side, the first axis was related to the number of autochthonous breeds and the regulating ES indicators. Regarding the study areas, the productivity–trade-off axis was positively associated with the Swedish wood-pastures and negatively associated with the Romanian wood-pastures. The second axis, identified as crop production–related trade-offs, was associated, on the positive side, with cereal production, but was negatively associated with all cultural services, especially social events and wildlife-related recreation activities, and the regulating ES indicators. All study areas were positively associated to each other, except the Spanish study area of Llanos de Trujillo. The third axis, identified as multifunctionality-related trade-offs, was associated, on the positive side, with the number of products and the regulating ES indicators and, on the negative side, with animal production. This axis was strongly positively associated with the Spanish study area of La Serena and negatively with the Swedish wood-pastures. Finally, the fourth axis, named accessibility-related trade-offs, was positively associated with outdoor recreation and wildlife-related recreation. These trade-offs were positively related with wood-pastures in Östergötland and southern Transylvania and negatively with both Spanish study areas.

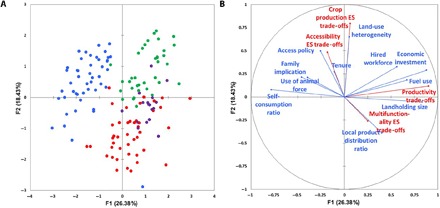

Linkages between ES trade-offs and SES properties

We found moderately and strongly positive and negative correlations between the identified ES trade-offs and the biophysical, social, economic, governance, and technological SES properties (Table 2). The multiple factor analysis (MFA) linking trade-offs and system properties absorbed 75% of the variability in the first four axes and revealed a complex pattern of interactions between trade-offs, SES properties, and geographical locations (Fig. 4). The multifunctionality- and productivity-related trade-offs were positively associated with high values in the size of the landholding, fuel use, economic investment, and hired workforce but were negatively associated with family involvement in management, use of animal workforce, and self-consumption from the total production. Crop production–related trade-offs were positively associated with larger proportions of private landownership and high heterogeneity. Multifunctionality-related trade-offs were positively associated with a high proportion of local products distributed and large landholding sizes and negatively associated with nonrestrictive farm access policies, high family involvement in management, and use of animal workforce. Accessibility-related trade-offs were strongly correlated with the relative openness/restrictiveness of farm access policy.

Table 2. Correlation (Pearson) between the management-related ES trade-offs and SES drivers of change.

Figures in bold indicate strong correlations (r > |0.3| ).

|

SES properties |

Indicators |

Productivity-related trade-offs |

Crop production–related trade-offs |

Multifunctionality-related trade-offs |

Accessibility-related trade-offs |

| Biophysical | Land-use diversity | 0.062 | 0.504 | 0.048 | 0.279 |

| Property size | 0.623 | −0.002 | 0.413 | −0.110 | |

| Social | Hired workforce | 0.432 | 0.237 | 0.101 | 0.101 |

| Local products distribution ratio | 0.285 | −0.255 | 0.351 | −0.072 | |

| Family involvement | −0.245 | 0.121 | −0.143 | 0.118 | |

| Self-consumption ratio | −0.702 | 0.083 | 0.046 | 0.184 | |

| Governance | Proportion of the landholding privately owned | −0.069 | 0.303 | 0.005 | −0.031 |

| Access policy | −0.032 | 0.098 | −0.318 | 0.497 | |

| Technological | Fuel consumption | 0.508 | 0.203 | 0.091 | −0.087 |

| Use of animal workforce | −0.408 | 0.180 | −0.045 | 0.112 | |

| Economic | Economic investment | 0.812 | 0.286 | −0.019 | −0.117 |

Fig. 4. Biplot of the first two axes of the MFA (48% of the variability absorbed).

(A) Coordinates of the observations. The color of the labels indicates the study area (blue, southern Transylvania; green, Östergötland; red, Llanos de Trujillo; purple, La Serena). (B) Correlation biplot of the variables included.

Landholders’ perceptions of landscape values and threats

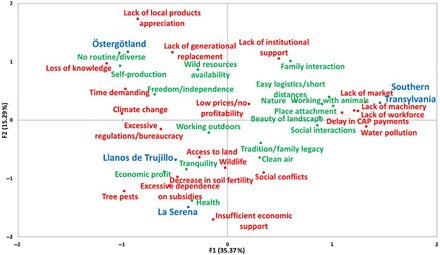

On the basis of the coded landscape values and perceived threats to the current management of wood-pastures, we observed a differentiated pattern in landowners’ and managers’ perceptions in the study areas. A multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) revealed two main components, which explained 50.67% of the variability and spatially segregated perceived threats and landscape values by study area (Fig. 5). Swedish landholders especially appreciated working in wood-pastures because the activity contributes to their well-being by giving them autonomy and freedom and allowing them to escape their everyday routine; they felt threatened by the lack of social and political recognition of their work and products, the lack of new generations continuing agriculture, and the loss of knowledge in the region. Managers and landowners in Romania especially appreciated working outdoors, being in contact with nature and animals, and feeling personally attached to the wood-pastures. They also appreciated the fact that the rural landscape allows them to strengthen social relationships and that they do not need to travel far in their everyday routine. On the other hand, they expressed concerns regarding the lack of technology and specialized workforce in land management, delayed agricultural support payments, and unfair prices that do not reflect the true value of their products. Respondents in the two Spanish study areas generally appreciated the peacefulness and tranquility of working in the area. They also emphasized that the rural landscape contributes to their health and that wood-pastures are their main income source. However, they felt too dependent on common agricultural policy (CAP) payments; they had difficulties in accessing new farmland and perceived different environmental threats: tree pests, a decline in soil fertility, and wildlife as a pest vector.

Fig. 5. Scatter plot of the first two axes of the MCA.

Landscape values are in green, perceived threats are in red, and study areas are in blue.

DISCUSSION

Similar landscape, dissimilar ecosystem service supply

Our results show that wood-pastures in Europe provide, beyond single-commodity production, a wide variety of ES, spanning all service categories. Beyond general patterns, our cross-site comparison reveals a situation in which the levels of individual ES supply vary greatly between European regions (Fig. 3). In Sweden, wood-pastures show the highest levels of management intensity, sustaining a moderately diverse but intensive production that is mainly focused on timber harvesting and animal grazing. This is accompanied by a high supply of cultural ES, where wood-pastures have historic and cultural values and play an important role in game hunting and other recreational activities. These values are in line with previous studies in the south of Sweden that identified wood-pastures as playing an important role in the conservation of cultural heritage and the supply of diverse recreational ES while maintaining commodity production (37, 38). In contrast, wood-pastures in Romania maintain similarly high levels of animal production while using less input-dependent management practices (39). Although previous studies indicate a general appreciation of wood-pasture landscapes and their values for relaxation and recreation (40), our results indicate that beyond that general recognition, wood-pastures are currently not used as arenas for cultural gatherings, and local communities do not recognize any historically or culturally relevant features. This situation is interesting because the Saxon cultural region of Transylvania is considered the most important region for ancient oak wood-pastures in central and eastern Europe (41). When specifically asked, local actors recognized several cultural and historical values of large old trees from these wood-pastures (42). Representing an intermediate situation, Spanish wood-pastures combine livestock production with a diverse and low-intensity production of firewood and crops with game hunting and other recreational activities.

Therefore, we find that similar landscapes with comparable spatial and structural configurations can provide very different sets of ES. This variability is expressed when comparing across study areas. However, wood-pastures differ in their supply of ES also within regions depending on landholders’ interests and society’s use of the wood-pastures (see table S2). These contrasts in ES supply add another layer of complexity to the valuation of the ES provided by these multifunctional landscapes as it would be inadequate to compare the productivity of two systems designed and maintained for different purposes with single indicators. Given two similar wood-pastures, a valuation based on their potential for recreation will probably yield a different result to a valuation based on their contributions to biodiversity conservation or to commodity production. The ES service framework is a useful tool not only to take stock of the multiple products and activities that take place in wood-pastures but also to integrate their environmental and cultural values, which will differ according to the local context. In Europe, where agricultural and several environmental policies are articulated at the transnational level, policies to conserve or promote multifunctional landscapes, such as wood-pastures, need to acknowledge and integrate the different roles a system can play in different contexts to achieve a fair and equal valuation.

Management dimensions governing trade-offs of ecosystem services

Traditionally, trade-off analysis has been focused on identifying trade-offs among different land uses (30, 43). Moreover, in agricultural systems, the identification of trade-offs has focused on the effects of single management dimensions, typically by assessing the effect of enhancing a relevant ES (25) over the rest, or the effect of increasing/decreasing management intensity (44, 45). Given the complexity and place-based character of traditional agricultural systems, as wood-pastures, the single focus on land-use types appears too simplistic and might lead to flawed and excessively rigid policies. Although the four study areas considered are dominated by wood-pastures, the provision of ES varies greatly within and between them, which implies that there are inherent trade-offs related to the different management styles.

Our results confirm hypothesis 1 and show that in wood-pastures, the mechanisms leading to trade-offs and synergies of ES are linked with multiple aspects of management. In particular, we identified four main dimensions of management that control ES associations: the degree of management intensity, the extent to which the system is focused on crop production, the extent of multifunctionality of the system, and the degree of accessibility of a wood-pasture to the general public (Table 1).

The most influential dimension of management, which generates the strongest trade-offs, is the extent to which the focus is on commodity production and the degree of management intensity. Our results show that single-commodity production comes at the expense of regulating ES with increased dependence on external inputs. This may be the case for increased crop yields (cases such as Östergötland or La Serena) or for importation of supplementary fodder (case of Llanos de Trujillo). These results are in line with the previous literature identifying negative relationships between provisioning and regulating ES in agricultural landscapes (21, 46, 47). Surprisingly, our results show that cultural ES were not negatively affected by management intensification. This is illustrated in the Swedish and Romanian cases. In Sweden, where landholdings showed the most intensive management practices, we found the highest use of the landscape for outdoor recreation, game hunting, and historical and cultural values, whereas Romanian wood-pastures, which are less intensively managed (as expressed by reduced input levels of capital, fertilizers, and pesticides), show the lowest levels of the former values. These results contradict previous assessments of ES trade-offs in agricultural landscapes (22), but are in line with assessments performed in southern Sweden (29, 37) that link high cultural ES to complex agricultural landscapes.

The relationships described between cultural and provisioning ES reveal two different planning and management strategies within a multifunctional landscape. On the basis of our results, we can identify Swedish landholders as advocates of “land sparing,” dividing their land into “monofunctional entities,” some composed of cropland, permanent grasslands, and coniferous forest devoted to intense commodity production (where trade-offs between provisioning and regulating ES occur), while maintaining patches of wood-pastures, which are managed and maintained to enhance their cultural and recreational value. In contrast, Romanian and Spanish wood-pastures are examples of “land sharing,” which integrates commodity production and cultural and recreational uses in the same management unit. These two antagonistic strategies have roots in the way in which landholders perceive land use and its potential for ES supply. In Sweden, wood-pastures are perceived as recreational landscapes and strongholds of cultural identity, which are in conflict with production (38), whereas in Romania (40) and Spain (16, 17), they are perceived as an integrated management unit that simultaneously provides provisioning, regulating, and cultural ES.

The second dimension of wood-pasture management that governs ES trade-offs relies on the importance of crop production within overall land management. Increasing crop production is commonly accompanied by a decrease in the recreational use of the landholding. Crop production as a land use is largely incompatible with recreational use, because the latter can affect crop yields. However, crop production plays an essential role in supplying supplementary fodder and is a central element in increasing self-reliance and independence from external inputs. Croplands within wood-pasture landholdings also play an important role in providing habitat for multiple protected bird species, some of which are an important attraction for bird-watchers, as is the case in Llanos de Trujillo (48).

The third dimension accounts for the role of multifunctional versus monofunctional management. Our results show that increasing multifunctionality is a strategy that can potentially maintain animal production and recreational uses while reducing dependence on external inputs. Multifunctionality is the management dimension with the highest number of synergies among ES, integrating production, recreation, and conservation within the same multifunctional unit. Returning to the land sparing/land sharing duality, integrated management (exemplified by the study areas of La Serena, Llanos de Trujillo, and southern Transylvania), which is often closer to traditional management, makes broader use of the available resources so that they can supply a wider set of ES.

The final management dimension accounts for the relative openness/restrictiveness of landholding access policy. This has a significant effect on the provision of cultural services. Access to the land controls and regulates recreational uses and, thus, broader landscape values. These results demonstrate that accessibility is the most important factor influencing people’s use of the landscape.

Howe et al. (49) found in a meta-analysis that whereas trade-offs were the most common type of ecosystem service association, synergies were rare and only appeared when landowners managed to avoid or overcome economic pressures. This conclusion appears to be true in our analysis. The first two management dimensions reflect trade-offs that can be directly or indirectly associated with economic motivations to increase profitability. However, in the case of the third and fourth dimensions, we mostly identify synergistic associations, which represent alternative management strategies to increase ES supply without harnessing profitability. Therefore, our results show that policies aiming to increase ES supply in agroecosystems should be oriented to increase the multifunctionality of management and to make the land more accessible to the general public.

A social-ecological approach to assessing coproduction of ecosystem services

Recently, Cavender-Bares et al. (50) presented a sustainability framework for landscape planning that associates ES trade-offs in terms of two dimensions: biophysical constraints and stakeholders’ different preferences/values. Our analysis goes beyond these two dimensions—by comparing four study areas dominated by the same land use but in very different stages of social-ecological development—consistently linking the outcomes of these trade-offs with different SES properties.

Following our proposed framework (Fig. 2), our analysis of ES trade-offs showed how different outcomes (O) of ES coproduction depend on decisions encompassing different management dimensions. These decisions do lead to complex interactions (I) between ecosystem processes that generate trade-offs and synergies of ES that will promote the supply of some ES at the expense of others. Our results further reveal how these trade-offs of ES are driven by diverse SES properties (Fig. 4 and Table 2). These different properties will have an impact on landowners and managers, who will ultimately determine the processes that maintain the composition and structure (RS) of the landscape and regulate its management and use (GS). Thus, our analysis confirms hypothesis 2 and shows that management decisions depend not only on the range of management options that are dictated by the environmental characteristics of the land (for example, climate and soil fertility) but also on the social, economic, technological, and biophysical properties of the system, which will enlarge or constrain the capacity of landholders to shift management one way or another for each of the identified management dimensions.

In the case of the productivity-related trade-offs, the MFA shows that the intensity of the management is dependent on the economic and technological level of the SES (Table 2, F1). Our results place the four study areas on a continuum of productivity associated with management intensification, where the Swedish and Romanian wood-pastures are placed at opposite extremes, whereas the two Spanish study areas are in the middle. The outcomes of the analysis suggest that the increased productivity observed in Swedish wood-pastures is associated with the fact that they have access to more financial capital and technology. This situation allows greater investment not only in external inputs (pesticides, improved seeds, fertilizers, etc.) but also in specialized workforce (increased number of hired employees) and in machinery to streamline management processes (increased fuel consumption). In contrast, the Romanian wood-pastures are often managed for semi-subsistence (high self-production ratio), with low use of technology (greater use of animal workforce) and low economic investment.

As opposed to abovementioned patterns, multifunctionality-related trade-offs are not associated with the economic and technological development of the system. Instead, multifunctional management is related to biophysical properties (size of the landholding), governance (policy regarding access to the landholding), and the presence of local distribution networks (local distribution ratio) (Table 2, F3). This result is interesting, as multifunctionality is the management dimension associated with more ES synergies. In the current context of global, delocalized markets, farmers are being encouraged to simplify their production with adverse consequences for the supply of ES (38). Our results suggest that this trend could be reverted by policies focused on stimulation of local distribution networks. These policies would encourage diversification by promoting local products while helping to build local brands by associating local production with the multifunctional landscape. Our results also show increased multifunctionality in the management of large properties with low accessibility to the general public. We associate this pattern with the difficulties connected to integrating multifunctional management in the CAP, whose payments are, to a great degree, based on the size of the landholding. As a consequence, landholders tend to cease the production of secondary products, commonly less profitable, to increase stocking rates.

The MFA shows that crop-related trade-offs are related with governance properties (Table 2, F2), supporting previous findings that indicate that lower risk operations are connected to rented land tenure (38). Finally, the analysis showed that the property access policy is the most relevant factor that regulates the public’s recreational use of the wood-pastures (Table 2, F4). This finding is in line with previous studies that identify accessibility as being a better predictor for landscape appreciation and use than land-use cover and other landscape features (17).

Perceptions of landscape values and current threats

Previous studies have analyzed the perception of ES supply in Spanish (16, 17), Swedish (38), and Romanian (42) wood-pastures. Our analysis differed from these by specifically targeting land managers and landowners as ultimate decision makers regarding wood-pasture management. In addition, we expanded our analysis beyond ES supply to include wood-pasture threats and relations to quality of life. Our results show that landholders, beyond sharing some common perceptions regarding values associated with their profession (working outdoors, working with animals), have a regionally different understanding of the landscape and how it contributes to their well-being, reflecting the different regional characteristics, properties, and roles that wood-pastures play in each SES (Fig. 5). These results confirm our hypothesis 3: The different values attributed to wood-pastures in each region mirror the different roles a similar landscape can play across Europe. They all share a similar spatial configuration, in our particular case combining trees at different densities with pasture, and a main principal objective of raising animals. However, the state of the SES varies greatly across study areas, which results in significant differences in ES supply depending on the diverse needs, values, and motivations of the people working in them.

Swedish wood-pastures, which are a relict landscape in this area, are perceived as providers of cultural values and are mostly used for recreational purposes. Here, the management of wood-pastures reflects landowners’ and managers’ personal statements against a strongly delocalized market and a rather intensive agricultural landscape (high values of freedom, independence, and self-production). This contrasts with how wood-pastures are perceived in Romania, where wood-pastures are often part of semi-subsistence systems, where local households are highly reliant on their self-production and are the direct beneficiaries of most of the ES. Hence, wood-pastures play a central role in the articulation of social interactions at the local level and the general functioning of the community (high appreciation of the landscape for social interactions and place attachment). Finally, in both Spanish study areas, landholders perceive wood-pastures as central productive elements because they are profitable and essential for conducting agricultural production (51). High-quality meat-based products are associated with wood-pasture management in the Spanish collective imagination and are supported by branding strategies that promote the consumption of wood-pasture products. Hence, this role is reflected in landholders’ perspectives as they consider wood-pastures to be their source of profit (perceived economic value) while they recognize the environmental role they play in the landscape (perceived values in cleaning the air and health). These trends in the appreciation of ES have also been observed among rural inhabitants in multifunctional landscapes across Europe. This illustrates that cultural services are more appreciated in regions with high gross domestic product/capita (GDP) and population density, whereas provisioning services are emphasized in regions with low GDP and population density, and a higher share of people working in agriculture for subsistence farming.

The different roles that wood-pasture play in SES can also be identified in the threats that landholders perceive, reflecting the different stages in the development of the SES and the diverse inherent dynamics of each study area. Romanian wood-pastures are in the process of an adaptation to the European agricultural support schemes (perceived delay in CAP payments) and face challenges related to increasing the productivity of the system (perceived lack of technology, specialized workforce, and low profitability) while controlling the overpressure on their natural resources. In contrast, landholders in Spain face threats related to the environmental and economic sustainability of landscapes that are managed to achieve their maximum productive potential (perceived dependence on CAP payments, lack of tree regeneration, and wild animals as pest vectors). In Sweden, landholders feel encouraged to switch their management to more productive land uses to increase profit (perceived low profitability). This process is further exacerbated by the gradual development of Swedish wood-pastures into solely recreational and cultural landscapes, and the loss of local/ecological knowledge regarding how to integrate them into production (perceived loss of knowledge and lack of a generational succession).

Policy implications

Overall, our analysis reveals that ES associations are complex, have multiple origins, and do not follow simple win-win interactions or single causalities, but are instead controlled by different land management and farm policy dimensions. In wood-pastures, policies that are oriented toward enhancing provisioning, regulating, and cultural ES should be focused not only on regulating the intensity of management but also on the accessibility and multifunctionality of the systems. Multifunctionality is one of the objectives of the European Union’s Biodiversity Strategy to 2020 (52). A way to promote multifunctional management would be to lower the priority given to farm surface in current payment schemes in favor of indicators that promote diversification. These schemes are currently being implemented on arable land by supporting crop diversification to reinforce biodiversity conservation within the “Greening” strategy of the CAP for 2015–2020. We advocate extending these efforts to grazed land to acknowledge the role that woody vegetation plays in the ecosystem to minimize ES trade-offs. The current CAP fails to capture some of the most important values of European traditional agroecosystems as it builds on simplistic land-use type categorizations while disregarding the multifunctional character of systems such as wood-pastures. These systems require low-intensity management and the presence of semi-natural habitats. To successfully enhance ES supply, future CAP rules should, on the one hand, use pillar I to link direct payments more strongly and generally with management practices benefiting the environment. On the other hand, pillar II should focus more on the place-specific social-ecological properties of land-use systems and address different management models individually.

Perhaps, the most relevant message derives from the context specificity of the results in each study area. In our study, we compared four landscapes that, although being dominated by the same land use, are very different in their local contexts, the values they hold, and the challenges they face. To ensure a positive future for agroecosystems, it is necessary to embrace this diversity and design policies that are adapted to the different regional contexts. Policies to enhance ES provision in Swedish wood-pastures (such as stimulation of local distribution networks and promotion of local products through strategies of landscape labeling) do not match with the ones that might be necessary to boost ES supply in the analogous Romanian agroecosystems (such as improved access to markets and support to address technological gaps) or the analogous Spanish ones (such as maintenance and restoration of public paths and drove roads to make the landscape more accessible to the general public, and incentive schemes to integrate cereal production within wood-pastures).

To achieve these goals, transformative strategies are required to acknowledge that landscapes are not static and that are based on the premise that direct links between people and nature are preferable to indirect links based on incentive payments. Linking with Food and Agriculture Organization’s strategic objectives to make agriculture more sustainable, land managers need to be placed in the frontline of decision-making by establishing a continuous dialogue that monitors the social-ecological properties of farming systems and ensures a sustainable agricultural development while improving the quality of life of local stakeholders. Potential incentives to promote a management that enhances ES would be further supported by integrated landscape policies that promote the development of local distribution networks, product labeling and certification, and programs to maintain traditional agricultural knowledge.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area description

The study was conducted at four sites in three European countries: Östergötland (Sweden), southern Transylvania (Romania), and Llanos de Trujillo and La Serena (Spain) (Fig. 2). Each site constitutes an internally coherent territorial unit in terms of landscape, land uses, and socioeconomic characteristics (Table 3). All study areas are agricultural landscapes in which wood-pastures that are mainly composed of oak trees are the most characteristic landscape elements. However, the conservation status and prominence of wood-pastures in the landscape and the social-ecological trajectories of each system differ greatly.

Table 3. Basic characteristics and land uses of the four study areas.

| Study area |

Biogeographic region |

Mean annual rainfall (mm) |

Mean annual temperature (°C)* |

Mean altitude and range (m)† |

Population density (inh./km2) |

Wealth level (gross domestic product/capita in €)‡ |

| Southern Transylvania | Continental | 627 | 9.4 | 574 (440–761) |

26 | 4,600 |

| Östergötland | Boreal | 641 | 5.2 | 142 (0–243) |

27 | 34,440 |

| La Serena | Mediterranean | 594 | 19.1 | 519 (354–840) |

11 | 15,600 |

| Llanos de Trujillo | Mediterranean | 569 | 19.2 | 424 (209–781) |

13 | 15,700 |

| Study area | Surface (ha) | Agricultural land (%)§ | Arable land (%)§ | Forest and semi- natural areas (%)§ |

Soil type¶ | Mean slope (%)† |

| Southern Transylvania |

23,773 | 63.1 | 17.7 | 34.0 | Stagmic luvisol | 11.9 |

| Östergötland | 116,696 | 32.8 | 27.5 | 57.7 | Eutric cambisol | 4.8 |

| La Serena | 63,768 | 73.4 | 27.9 | 20.3 | Gleyic acrisol | 7.4 |

| Llanos de Trujillo | 94,048 | 45.8 | 5.9 | 16.2 | Dystric regosol | 5.7 |

*Extracted from Metz et al., Surface temperatures at the continental scale: Tracking changes with remote sensing at unprecedented detail. Remote Sensing 6, 3822–3840 (2014).

†Calculated from the Digital Elevation Map of GMES RDA project (www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/eu-dem).

‡Year of reference: 2011. NUTS 3 level. Sources: Eurostat, Swiss Federal Statistics Office.

§According to CORINE Land Use 2006. Agricultural land includes arable and grazing land (including natural grasslands).

¶Extracted from A. Jones, L. Montanarella, R. Jones, Soil Atlas of Europe (European Commission, 2005), p. 128.

The study areas of Llanos de Trujillo (formed by the municipalities of Trujillo, La Cumbre, Aldea del Obispo, and Torrecillas de la Tiesa) and La Serena (formed by the municipalities of Campillo de Llerena, Retamal de Llerena, Higuera de la Serena, and Zalamea de la Serena) are located in the region of Extremadura, in southwestern Spain (Fig. 1, A and C). Dominated by holm oak (Quercus ilex) wood-pastures, named dehesas, agricultural land is mostly concentrated on large landholdings that have often belonged to the same families for several generations. In the past, each dehesa was used to support several households and was significantly reliant on unpaid labor. The modernization of the Spanish society and the economy in the 1970s motivated owners to shift management toward activities that required less labor (for example, cattle breeding instead of sheep breeding and meat breeds instead of milk breeds) and to reduce the diversity of their production activities. The main environmental difference between Llanos de Trujillo and La Serena is the rather fertile soils and flat lands in the latter, which allow dehesas in this area to be commonly intercropped with cereals and legumes in a rotational cycle of 4 to 10 years. In contrast, in Llanos de Trujillo, cereal production has almost disappeared, whereas the promotion and enhancement of habitat for game hunting have increased.

The study area of southern Transylvania (formed by the municipalities of Rupea, Viscri, Bunești, and Messendorf) is located in the Saxon region of southern Transylvania (Fig. 1D). Traditionally, grazing and forestry were crucial activities in this region. The use of forests and pastures was managed in a communal way, where each individual in the community had rights and obligations concerning their use. Thus, the structure of the landscape and its traditional use is inextricably linked to the local communities. After the fall of the communist regime in 1989 and Romania’s accession to the European Union in 2007, economic interest in the region has been increasing not only due to its natural and cultural heritage but also for its agricultural landscape and potential for economic intensification.

The study area of Östergötland (composed of the municipality of Linköping), which is located in the southeast of Sweden (Fig. 1B), has one of the largest remnant areas of pedunculated oak (Quercus robur) and sessile oak (Quercus petraea) wood-pastures in Sweden, where most traditional grazing systems disappeared during the 19th century. Not all wood-pastures were transformed into other land uses, especially in Östergötland, where they still represented a key management resource. Nowadays, the traditional management of wooded meadows and grazed wood-pastures has been slowly abandoned, and currently, the remaining wood-pastures have been integrated into the farms and kept for their cultural and historic values as well as for the recreational activities that take place in them such as outdoor sports, orienteering competitions, or game hunting.

Data collection

Data were collected through semistructured face-to-face interviews with landholders, which were designed to capture the main characteristics of management in the wood-pasture as well as the landholders’ sociodemographic characteristics and personal views and opinions. Our semistructured questionnaire comprised 50 items with potential follow-up questions for clarification purposes (full interview translated into English in table S1). Some of the questions were adapted during the translation to match the local context or to suit the terminology used in each native language when necessary. Interviews were performed between the summer of 2015 and spring of 2017 (May to June 2015 in Llanos de Trujillo, March to April 2016 in La Serena, August to September 2016 in Östergötland, and February to May 2017 in southern Transylvania). Landholders were identified by snowball sampling (53), where a number of initial contacts were made on the basis of local facilitators. Starting from these, other landholders who fulfilled the requirements were contacted. The total number of owners and/or managers interviewed was 36 in Östergötland, 46 in southern Transylvania, 42 in Llanos de Trujillo, and 19 in La Serena. The land under their management covered a total surface of 395.82 km2, which represents 12% of the total and 25% of the agricultural surface in the study areas.

Ecosystem service indicators

We collected the values for indicators of ES to assess the coproduction of ES in each wood-pasture covering provisioning, regulating, and cultural ES categories. For provisioning services, we used the total number of products, animal production, cereal production, timber and firewood production, and maintenance of genetic resources as indicators. Number of products accounted for the total number of commercial commodities and/or activities marketed on the landholding. Animal production accounted for the total number of livestock units present on the wood-pasture divided by the total surface area of the landholding. One livestock unit corresponded to the food necessities of a cow of 500 kg, not pregnant or lactating. The equivalencies in livestock units for the remainder of the animals were based on the regulatory document Decreto 14/2006 from the Junta de Andalucía (Decreto 14/2006, www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2006/14/d1.pdf). Cereal production accounted for the percentage of the property devoted to crop production. Timber and firewood production comprised the number of tons of timber and firewood harvested in a year per hectare of land. Maintenance of genetic resources accounted for the number of autochthonous breeds present in the wood-pasture.

Regarding regulating ES, we collected the values for two indicators of agricultural intensification that have previously been associated with the reduction in regulating ES on European farmland (22, 26, 29, 54): mineral inputs and capital inputs. We used these as inverse indicators of regulating services. Mineral inputs account for the total number of tons of mineral fertilizer used per hectare on the landholding per year. Capital inputs comprise the total amount of euros spent per hectare per year on expenses, that is, pesticides, fuel, salaries, imported animal fodder, and fertilizers.

Finally, to assess the supply of cultural ES, as indicators, we used hunting, which accounted for the presence or absence of recreational hunting activities; recreational events, which comprised the use or otherwise of the wood-pasture for recreational events (family gatherings, social events, public festivals, etc.); wild resources harvesting, which covered the harvesting of wild non-wood forest products (mushrooms, berries, flowers, etc.); outdoor recreation, which accounted for the use or otherwise of the wood-pasture for outdoor activities (running, hiking, biking, etc.); wildlife-related recreation, which comprised the use or otherwise of the landholding for wildlife/biodiversity-related recreational activities (nature photographing, bird-watching, etc.); and historic and cultural features, which accounted for the presence or absence in the wood-pasture of landscape features of historic or cultural value (ancient graves, traces of past uses, religious landmarks, etc.).

System property indicators

To account for the biophysical, economic, governance, technological, and economic properties of the wood-pastures, we collected the values of 11 indicators at every property. To account for the biophysical characteristics, we assessed land-use heterogeneity, measured as the diversity of land use, with the Shannon index of diversity and the size of the landholding in hectares. To account for the social properties of the wood-pasture, we assessed the total number of hired employees (that is, the total number of hired non-family employees measured as individuals per month per year based on a 7.4-hour working day) and family involvement in the management, which accounted for the number of family members working in the wood-pasture (regardless of whether they were recognized economically or not). To account for the governance properties, we assessed self-consumption ratio, which accounted for the proportion of the farm production that was consumed on the landholding; local distribution ratio, which accounted for the proportion of the commercial production that was distributed locally; privately owned ratio, which accounted for the proportion of the property that was privately owned; and farm access policy, which accounted for the policy regarding accessibility on the property, which could be open (access to the wood-pasture is allowed) or restricted (access to the wood-pasture is not allowed). To account for the technological properties, we assessed fuel consumption (total amount of gas oil consumed per year in cubic meters) and use of animal labor on the land. Finally, to account for the economic properties, we assessed the economic investment, which comprised the total amount of euros invested per year to manage the landholding, excluding economic subsidy payments.

Perception of landscape values and threats to management

To assess landholders’ views, perceptions, and perspectives, we asked two open questions during the interview. The first was designed to capture perceptions regarding wood-pasture values and how wood-pasture management affected their quality of life (“How does working in this landscape contribute to your quality of life?”). The second question (“What are the main threats and difficulties you confront in your work?”) was designed to capture landholders’ perceived threats to their current management.

The answers to the first question were coded following the cultural values model (CVM), which was developed by Stephenson (55) and has been used previously to assess values in SES (20). The answers to the second question were categorized according to the STEEP framework categories (56).

Statistical analysis

To identify ES trade-offs, we performed a PCA for mixed data. This multivariate analysis technique allows binary and continuous data to be integrated by mixing a standard PCA for the quantitative variables with an MCA for the binary variables as special cases (57). To assess the potential geographical influence on the trade-offs, we included the study areas as supplementary variables. Thus, we projected them onto the principal components for interpretative purposes without intervening in the calculation of the eigenvalues (58). We used the R package PCAmixdata to do the calculations (57). The first four components of the PCA were selected for interpretation following the Kaiser-criterion (eigenvalues < 1).

To analyze the relationship between the ES trade-offs and SES properties, we performed a correlation analysis using Pearson index and MFA. MFA is a multivariate analysis technique that allows one to analyze and synthesize the information from different data sets, which facilitates the use of quantitative and qualitative data (59). The MFA successively carries out a PCA or an MCA depending on the variable type and stores the value from the first eigenvalue of each multivariate analysis to perform a weighted PCA. As input variables, we used the values of the factor loadings of each landholding for the four trade-offs calculated in the PCA. We related these values to the drivers of management (Table 2). As in the PCA, we included the study areas as supplementary variables to analyze geographical patterns without interfering in the calculation of the eigenvalues or coordinates of the variables. Again, we used the R package PCAmixdata to perform the calculations.

To analyze landholders’ perceived values and threats, we performed an MCA using the coded answers to the two open questions as inputs. The active variables were the presence/absence of the perception of each individual landscape value and threat. To infer potential geographical and cultural patterns, we again used the study areas as supplementary variables. The statistical analysis was performed using XLSTAT 2009 (60).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the 144 managers and landowners in the four study areas for participating in the study. We also acknowledge the contribution of L. Postigo Berroccal, V. Măcicăsan, E. Hartel, Á. Szapanyos, and H. Carlsson to the data collection. Funding: The authors acknowledge the funding received from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement no. 613520 (project AGFORWARD). Author contributions: M.T., T.P., and N.F. designed the research. M.T., G.M., and T.H. collected the data. M.T. analyzed the data. M.T. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors performed the research and wrote the paper. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are presented in the paper and/or the Supplementary materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/5/eaar2176/DC1

table S1. English version of the initial questions in the semistructured questionnaires.

table S2. Average (±SD) values of ES supply values for each study area.

table S3. Summary statistics of the MFA.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.T. Hartel, T. Plieninger, European Wood-Pastures in Transition: A Social-Ecological Approach (Earthscan from Routledge, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plieninger T., Hartel T., Martín-López B., Beaufoy G., Bergmeier E., Kirby K., Montero M. J., Moreno G., Oteros-Rozas E., Uytvanck J. V., Wood-pastures of Europe: Geographic coverage, social–ecological values, conservation management, and policy implications. Biol. Conserv. 190, 70–79 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torralba M., Fagerholm N., Burgess P. J., Moreno G., Plieninger T., Do European agroforestry systems enhance biodiversity and ecosystem services? A meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 230, 150–161 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huntsinger L., Oviedo J. L., Ecosystem services are social–ecological services in a traditional pastoral system: The case of California’s Mediterranean rangelands. Ecol. Soc. 19, 8 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 5.D. Jørgensen, P. Quelch, The origins and history of medieval wood-pastures, in European Wood-Pastures in Transition: A Social-Ecological Approach, T. Hartel, T. Plieninger, Eds. (Earthscan from Routledge, 2014), pp. 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergmeier E., Petermann J., Schröder E., Geobotanical survey of wood-pasture habitats in Europe: Diversity, threats and conservation. Biodivers. Conserv. 19, 2995–3014 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 7.R. Oppermann, Wood-pastures as examples of European high nature value landscapes-functions and differentiations according to farming, in European Wood-Pastures in Transition: A Social-Ecological Approach, T. Hartel, T. Plieninger, Eds. (Earthscan from Routledge, 2014), pp. 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bugalho M. N., Caldeira M. C., Pereira J. S., Aronson J., Pausas J. G., Mediterranean cork oak savannas require human use to sustain biodiversity and ecosystem services. Front. Ecol. Environ. 9, 278–286 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoate C., Báldi A., Beja P., Boatman N. D., Herzon I., van Doorn A., de Snoo G. R., Rakosy L., Ramwell C., Ecological impacts of early 21st century agricultural change in Europe—A review. J. Environ. Manage. 91, 22–46 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plieninger T., Bieling C., Resilience-based perspectives to guiding high-nature-value farmland through socioeconomic change. Ecol. Soc. 18, 20 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bignal E. M., McCracken D. I., The nature conservation value of European traditional farming systems. Environ. Rev. 8, 149–171 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 12.P. Campos, L. Huntsinger, J. L. Oviedo, P. F. Starrs, M. DIaz, R. B. Standiford, G. Montero, Mediterranean Oak Woodland Working Landscapes (Springer Netherlands, 2013), vol. 16. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer A., Eastwood A., Coproduction of ecosystem services as human–nature interactions—An analytical framework. Land Use Policy 52, 41–50 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palomo I., Felipe-Lucia M. R., Bennett E. M., Martín-López B., Pascual U., Chapter Six - Disentangling the pathways and effects of ecosystem service co-production. Adv. Ecol. Res. 54, 245–283 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manning A. D., Fischer J., Lindenmayer D. B., Scattered trees are keystone structures—Implications for conservation. Biol. Conserv. 132, 311–321 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garrido P., Garrido P., Elbakidze M., Angelstam P., Plieninger T., Pulido F., Moreno G., Stakeholder perspectives of wood-pasture ecosystem services: A case study from Iberian dehesas. Land Use Policy 60, 324–333 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fagerholm N., Oteros-Rozas E., Raymond C. M., Torralba M., Moreno G., Plieninger T., Assessing linkages between ecosystem services, land-use and well-being in an agroforestry landscape using public participation GIS. Appl. Geogr. 74, 30–46 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sereke F., Graves A. R., Dux D., Palma J. H. N., Herzog F., Innovative agroecosystem goods and services: Key profitability drivers in Swiss agroforestry. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 35, 759–770 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pagiola S., Ramírez E., Gobbi J., de Haan C., Ibrahim M., Murgueitio E., Ruíz J. P., Paying for the environmental services of silvopastoral practices in Nicaragua. Ecol. Econ. 64, 374–385 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felipe-Lucia M. R., Comín F. A., Bennett E. M., Interactions among ecosystem services across land uses in a floodplain agroecosystem. Ecol. Soc. 19, 20 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodríguez J. P., Douglas Beard T. Jr, Bennett E. M., Cumming G. S., Cork S. J., Agard J., Dobson A. P., Peterson G. D., Trade-offs across space, time, and ecosystem services. Ecol. Soc. 11, 28 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maes J., Egoh B., Willemen L., Liquete C., Vihervaara P., Schägner J. P., Grizzetti B., Drakou E. G., La Notte A., Zulian G., Bouraoui F., Paracchini M. L., Braat L., Bidoglio G., Mapping ecosystem services for policy support and decision making in the European Union. Ecosyst. Serv. 1, 31–39 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martín-López B., Iniesta-Arandia I., García-Llorente M., Palomo I., Casado-Arzuaga I., García Del Amo D., Gómez-Baggethun E., Oteros-Rozas E., Palacios-Agundez I., Willaarts B., González J. A., Santos-Martín F., Onaindia M., López-Santiago C., Montes C., Uncovering ecosystem service bundles through social preferences. PLOS ONE 7, e38970 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersson E., Mcphearson T., Kremer P., Gomez-Baggethun E., Scale and context dependence of ecosystem service providing units. Ecosyst. Serv. 12, 157–164 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Power A. G., Ecosystem services and agriculture: Tradeoffs and synergies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 365, 2959–2971 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raudsepp-Hearne C., Peterson G. D., Bennett E. M., Ecosystem service bundles for analyzing tradeoffs in diverse landscapes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 5242–5247 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ament J. M., Moore C. A., Herbst M., Cumming G. S., Cultural ecosystem services in protected areas: Understanding bundles, trade-offs, and synergies. Conserv. Lett. 10, 440–450 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baró F., Gómez-Baggethun E., Haase D., Ecosystem service bundles along the urban-rural gradient: Insights for landscape planning and management. Ecosyst. Serv. 24, 147–159 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Queiroz C., Meacham M., Richter K., Norström A. V., Andersson E., Norberg J., Peterson G., Mapping bundles of ecosystem services reveals distinct types of multifunctionality within a Swedish landscape. Ambio 44, 89–101 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cord A. F., Bartkowski B., Beckmann M., Dittrich A., Hermans-Neumann K., Kaim A., Lienhoop N., Locher-Krause K., Priess J., Schröter-Schlaack C., Schwarz N., Seppelt R., Strauch M., Václavík T., Volk M., Towards systematic analyses of ecosystem service trade-offs and synergies: Main concepts, methods and the road ahead. Ecosyst. Serv. 28, 264–272 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burton R. J. F., Schwarz G., Result-oriented agri-environmental schemes in Europe and their potential for promoting behavioural change. Land Use Policy 30, 628–641 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siebert R., Toogood M., Knierim A., Factors affecting European farmers’ participation in biodiversity policies. Sociol. Ruralis. 46, 318–340 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahnström J., Höckert J., Bergea H. L., Francis C., Skelton P., Hallgren L., Farmers and nature conservation: What is known about attitudes, context factors and actions affecting conservation? Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 24, 38–47 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Birge T., Herzon I., Motivations and experiences in managing rare semi-natural biotopes: A case from Finland. Land Use Policy 41, 128–137 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ostrom E., A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 325, 419–422 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mouchet M. A., Mouchet M. A., Lamarque P., Martín-López B., Crouzat E., Gos P., Byczek C., Lavorel S., An interdisciplinary methodological guide for quantifying associations between ecosystem services. Glob. Environ. Chang. 28, 298–308 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersson E., Nykvist B., Malinga R., Jaramillo F., Lindborg R., A social–ecological analysis of ecosystem services in two different farming systems. Ambio 44, 102–112 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garrido P., Elbakidze M., Angelstam P., Stakeholders’ perceptions on ecosystem services in Östergötland’s (Sweden) threatened oak wood-pasture landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 158, 96–104 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hartel T., Dorresteijn I., Klein C., Máthé O., Moga C. I., Öllerer K., Roellig M., von Wehrden H., Fischer J., Wood-pastures in a traditional rural region of Eastern Europe: Characteristics, management and status. Biol. Conserv. 166, 267–275 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hartel T., Fischer J., Câmpeanu C., Milcu A. I., Hanspach J., Fazey I., The importance of ecosystem services for rural inhabitants in a changing cultural landscape in Romania. Ecol. Soc. 19, 42 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hartel T., Hanspach J., Moga C. I., Holban L., Szapanyos Á., Tamás R., Hováth C., Réti K. O., Abundance of large old trees in wood-pastures of Transylvania (Romania). Sci. Total Environ. 613–614, 263–270 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hartel T., Réti K.-O., Craioveanu C., Valuing scattered trees from wood-pastures by farmers in a traditional rural region of Eastern Europe. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 236, 304–311 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deng X., Li Z., Gibson J., A review on trade-off analysis of ecosystem services for sustainable land-use management. J. Geogr. Sci. 26, 953–968 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tscharntke T., Klein A. M., Kruess A., Steffan-Dewenter I., Thies C., Landscape perspectives on agricultural intensification and biodiversity - ecosystem service management. Ecol. Lett. 8, 857–874 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bjö Rklund J., Limburg K. E., Rydberg T., Impact of production intensity on the ability of the agricultural landscape to generate ecosystem services: An example from Sweden. Ecol. Econ. 29, 269–291 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bengtsson J., Nilsson S. G., Franc A., Menozzi P., Biodiversity, disturbances, ecosystem function and management of European forests. For. Ecol. Manage. 132, 39–50 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kragt M. E., Robertson M. J., Quantifying ecosystem services trade-offs from agricultural practices. Ecol. Econ. 102, 147–157 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moreno G., Gonzalez-Bornay G., Pulido F., Lopez-Diaz M. L., Bertomeu M., Juárez E., Diaz M., Exploring the causes of high biodiversity of Iberian dehesas: The importance of wood pastures and marginal habitats. Agrofor. Syst. 90, 87–105 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Howe C., Suich H., Vira B., Mace G. M., Creating win-wins from trade-offs? Ecosystem services for human well-being: A meta-analysis of ecosystem service trade-offs and synergies in the real world. Glob. Environ. Chang. 28, 263–275 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cavender-Bares J., Polasky S., King E., Balvanera P., A sustainability framework for assessing trade-offs in ecosystem services. Ecol. Soc. 20, 17 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gaspar P., Mesías F. J., Escribano M., Pulido F., Sustainability in Spanish extensive farms (dehesas): An economic and management indicator-based evaluation. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 62, 153–162 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 52.European Commission, Our life insurance, our natural capital: An EU biodiversity strategy to 2020. COM(2011) 244 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 53.A. Bryman, Social Research Methods (Oxford Univ. Press, ed. 5, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 54.F. Herzog, K. Balázs, P. Dennis, J. Friedel, I. Geijzendorffer, P. Jeanneret, M. Kainz, P. Pointereau, Biodiversity Indicators for European Farming Systems (Agroscope Reckenholz-Tänikon Research Station ART, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stephenson J., The Cultural Values Model: An integrated approach to values in landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 84, 127–139 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 56.I. Brown, P. Harrison, J. Ashley, P. Berry, M. Everard, Robust Response Options: What Response Options Might Be Used to Improve Policy (UK National Ecosystem Assessment Follow-on Work Package Report 8, 2014).

- 57.M. Chavent, V. Kuentz-Simonet, A. Labenne, J. Saracco, Multivariate analysis of mixed data: The R Package PCAmixdata, https://arxiv.org/abs/1411.4911 (2014).

- 58.Gabriel S., Kydes A. S., A nonlinear complementarity approach for the National Energy Modeling System. Math. Comput. Sci. Div. (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abdi H., Valentin D., Multiple factor analysis (MFA). Encycl. Meas. Stat. (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 60.S. Addinsoft, XLSTAT software, version 9.0 (2009).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/5/eaar2176/DC1

table S1. English version of the initial questions in the semistructured questionnaires.

table S2. Average (±SD) values of ES supply values for each study area.

table S3. Summary statistics of the MFA.