Abstract

Purpose

In the United States, human immunodeficiency virus (HlV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) disproportionately impacts racial/ethnic minorities. We describe and evaluate trends in the Black-White and Hispanic-White disparities of new AIDS diagnoses from 1984 to 2013 in the United States.

Methods

AIDS diagnosis rates by race/ethnicity for people ≥13 years were calculated using national HIV surveillance and Census data. Black-White and Hispanic-White disparities were measured as rate ratios. Joinpoint Regression was used to identify time periods across which to estimate rate-ratio trends. We calculated the estimated annual percent change in disparities for each time period using log-normal linear regression modeling.

Results

Black-White disparity increased from 1984 to 1990, followed by a large increase from 1991 to 1996, and a smaller increase from 1997 to 2001. Black-White disparity moderated from 2002 to 2005 and rose again from 2006 to 2013. Hispanic-White disparity increased from 1984 to 1997 but declined after 1998. Black-White and Hispanic-White disparities increased for men who have sex with men during 2008 to 2013.

Conclusions

Recent increases in racial/ethnic disparities of AlDS diagnoses were observed and may be due in part to care continuum inequalities. We suggest assessing disparities in AIDS diagnoses as a high- level measure to capture changes at multiple stages of the care continuum collectively. Future research should examine determinants of racial/ethnic differences at each step of the continuum to better identify characteristics driving disparities.

Keywords: HIV, AIDS, Disparities, Racial/ethnic, Trends, Care

Introduction

In 2012, approximately 1.2 million individuals were living with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the United States [1]. Over 500,000 people living with HIV have ever received an acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AlDS) diagnosis and about 27,000 individuals are newly diagnosed with AlDS each year in the United States and dependent areas [2]. Since the introduction of effective combination antiretroviral therapy (ART), the annual rate of new AIDS diagnoses has decreased by more than half; however, important racial/ethnic disparities still remain [2,3].

HIV and AIDS disproportionately affect racial/ethnic minority groups including Blacks/African Americans (Blacks) and Hispanics/ Latinos (Hispanics). Blacks and Hispanics represent 12% and 16% of the total U.S. population, respectively, but accounted for 46% and 21% of new HIV diagnoses and 49% and 20% of new AIDS diagnoses, respectively, in 2013 [1,2,4]. Racial/ethnic disparities have received increased attention as the U.S. National HIV/AIDS Strategy (NHAS) and Healthy People 2020 have established objectives to decrease HIV-related inequalities [5,6]. These aims include increasing the proportion of Blacks and Hispanics with undetectable viral loads by 20% [5,6]. The outlined objectives rely heavily on improvements to the HIV care continuum, particularly for Blacks and Hispanics who may experience greater barriers to prevention and care due to socioeconomic factors such as poverty, access to health care, stigma, and language constraints [7]. Determining if and how we may achieve these goals will further depend on researchers’ ability to quantify and monitor trends in disparities over time.

According to surveillance data, Blacks and Hispanics have generally had higher rates of HIV and AIDS diagnoses compared with Whites [2,8]. Yet, limited research has evaluated the magnitude of these disparities and how they have evolved over time. One study found a significant decline in racial/ethnic disparities of AIDS diagnoses from 2000 to 2009 overall and for most age and sex subgroups, with the exception of young people aged 13–24 who experienced a significant increase in the Black-White disparity [9]. The authors reported that 90% of this increase among young people was due to rising AIDS diagnoses among men, suggesting increasing disparities for young Black men [9]. Although this study provides insight on racial/ethnic disparities during a period of time in the past decade, trends in racial disparities since the beginning of the HIV epidemic to present time have yet to be demonstrated.

Quantifying trends depends heavily on the years selected for analysis; thus, measuring trends in disparity over a longer time period may allow for better description and detection of changes in trends. Assessing disparity trends since the 1980s provides a historical context for how disparities emerged, were sustained, or possibly declined over the course of the HIV epidemic. For example, the number of AIDS diagnoses in the United States has declined for all racial/ethnic groups since the introduction of ART in 1996; however if and how racial/ethnic disparities in AIDS diagnoses have changed in the presence of effective treatment has not been shown to date [10–12]. Understanding how racial disparities have evolved over decades could also support hypothesis generation about which factors have contributed to changes in disparities.

This article describes and evaluates trends in the Black-White and Hispanic-White disparities of new AIDS diagnoses from 1984 to 2013. We first sought to empirically identify chronological time periods representing distinct eras of trends in racial/ethnic disparities. We then sought to test for the significance of disparity trends for each identified time period. Overall, our objective was to determine if, when, and how racial/ethnic disparities in AIDS diagnoses have changed over 30 years of the HIV epidemic in the United States and Puerto Rico.

Material and methods

Data on cases and rates of AIDS diagnoses by race for adults and adolescents aged 13 years and older were extracted from publicly available annual HIV surveillance reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for years 1984 to 2013 [13]. U.S. Census Bureau data were used to estimate annual population denominators for the general population by age and race (non-Hispanic Black; Hispanic; non-Hispanic White). For years when data on rates of AIDS diagnoses by age and race were reported directly in surveillance reports (1989–2007), these rates were used for analysis. For years when rates of AIDS diagnoses by age and race were not reported directly in surveillance reports (1984–1988 and 2008–2013), rates were calculated using age- and race-specific AIDS case counts as the numerator and intercensal (1984–1988, 2008–2009) or postcensal (2010–2013) annual population estimates as the denominator. The race-specific rate was calculated as the annual case counts divided by the annual population estimate for the race of interest multiplied by 100,000.

For Hispanics, rates of AIDS diagnoses by age and race for the United States and Puerto Rico were reported directly in surveillance reports from 1989 to 2002. For years when rates of AIDS diagnoses for U.S. Hispanics and Puerto Rico by age were not directly reported (1984–1988 and 2002–2013), rates were calculated using age- and race-specific AIDS case counts for both U.S. Hispanics and Puerto Rico as the numerator and either intercensal (1984–1988, 2002–2009) or postcensal (2010–2013) annual population estimates for U.S. Hispanics and Puerto Rico as the denominator. Population estimates for Puerto Rico were obtained from electronic archives from the Puerto Rico National Institute of Statistics or the U.S. Census Bureau and all were considered of Hispanic ethnicity. Further details on the data sources and estimation of annual age- and race-specific AIDS diagnoses rates are outlined in Table A of the Appendix.

Our outcome of interest was the AIDS diagnoses rate ratio, a relative measure of disparity comparing racial/ethnic groups. The rate ratios were calculated as the rate among the index racial/ethnic group (Non-Hispanic Blacks or Hispanics) divided by the rate among the reference group (Non-Hispanic Whites). After obtaining or calculating annual rate-ratio estimates, we then sought to quantify changes in these disparity measures over time. First, we empirically identified cut-point years for when trends in the disparities changed to determine the statistically significant trend periods. We used Joinpoint Regression software to test for significant “joinpoints,” or cut-point years, that would identify time periods with unique linear trends in the rate-ratio disparity measure. Joinpoint Regression is a statistical software frequently used in cancer surveillance to measure trends in cancer rates [14,15]. The program utilizes Monte Carlo permutation tests and grid search methods to determine the joinpoints at which statistically different trends occur in time [14,15]. We allowed the default settings of the Joinpoint software (maximum number of joinpoints for 30 datapoints = 5, minimum number years per trend period = 4, Bonferroni-adjusted alpha for permutation tests, alpha = 0.05 for significance of slope). For Joinpoint analyses, we imported annual log-transformed rate ratios and their standard errors and we performed analyses separately for each racial/ethnic comparison. Second, we quantified each disparity trend using estimated annual percent change (EAPC) measures. We applied log-normal linear modeling (PROC GLM) to determine the average annual change in the Black-White and Hispanic-White log-transformed rate ratios for each trend period. Beta estimates were transformed to obtain EAPCs for the rate-ratio disparity measures. We also modeled rateratio trends using an underlying Poisson distribution and the direction, strength, and significance of the terms were similar; however, model fit was poor. We conducted two additional subanalyses of the disparities stratified on (1) sex and (2) male-to-male sexual contact. Details on methods and available data for subanalyses are described in the Table 2 footnotes. Analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4.

Table 2.

Estimated annual percent change (EAPC) of the rate ratios for the Black-White and Hispanic-White racial/ethnic disparities in AIDS diagnoses by sex and male-male sexual contact, United States, 1991–2013 (BW males and females), 2002–2013 (HW males and females), and 2008–2013 (BW and HW MSM)

| Disparity | Joinpoint period | Years | EAPC | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black-White rate ratio | |||||

| Females | 1 | 1991–2001 | 4.4 | (3.3. 5.4) | <.01 |

| 2 | 2002–2013 | −0.3 | (−1.1, 0.6) | .55 | |

| Males | 1 | 1991–1996 | 11.4 | (9.5, 13.4) | <.01 |

| 2 | 1997–2001 | 2.7 | (0.4, 5.2) | .03 | |

| 3 | 2002–2005 | −3.4 | (−6.5, −0.2) | .04 | |

| 4 | 2006–2013 | 2.6 | (1.4, 3.8) | .01 | |

| MSM* | 1 | 2008–2013 | 6.0 | (3.8, 8.2) | <.01 |

| Non-MSM males*,† | 1 | 2008–2013 | −1.0 | (−4.9, 3.1) | .53 |

| Hispanic-White rate ratio‡ | |||||

| Females | 1 | 2002–2013 | −3.4 | (−4.6, −2.1) | <.01 |

| Males | 1 | 2002–2005 | −2.6 | (−4.9, −0.3) | .03 |

| 2 | 2006–2013 | 1.5 | (0.7, 2.4) | <.01 | |

| MSM* | 1 | 2008–2013 | 3.3 | (2.0, 4.6) | <.01 |

| Non-MSM males*,† | 1 | 2008–2013 | −1.5 | (−6.2, 3.4) | .43 |

AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; CI, confidence interval; EAPC, estimated annual percent change; MSM, men who have sex with men.

Notes: For the analysis stratified on sex, data for the Black-White disparity were limited to years 1991 through 2013 and data for the Hispanic-White disparity were limited to years 2002 through 2013 to remain consistent with surveillance reporting by sex during previously identified trend periods. For analyses stratified on malemale sex, data were limited to years 2008–2013 when estimated diagnoses for U.S. Black, Hispanic, and White MSM were reported.

MSM include both men who reported male-male sex and men who reported male-male sex and injection drug use. Rate denominators for MSM are an estimated proportion of 3.9% of the total male population ages 13 and older by race. Rate denominators for non-MSM males were therefore an estimated 96.1% of the total male population (Purcell et.al., 2012).16 These percentages were applied to all races.

Non-MSM males represent males who did not report male-male sexual contact.

Hispanics in these subanalyses represent mainland U.S. Hispanics only (do not include Puerto Rico) due to lack of data in surveillance reports on case counts in Puerto Rico by age, sex, and transmission category from 2002 to 2013.

Results

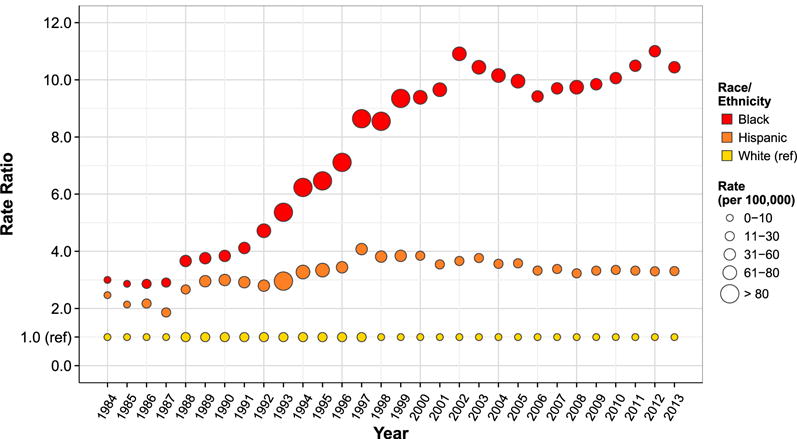

For the Black-White disparity, the Joinpoint Regression program identified four significant joinpoints (years 1991, 1997, 2002, and 2006) which corresponded to five different trend periods: 1984–1990, 1991–1996, 1997–2001, 2002–2005, and 2006–2013. For the Hispanic-White disparity, the method found only one significant joinpoint (1998), which corresponded to two different time periods: 1984–1997 and 1998–2013.

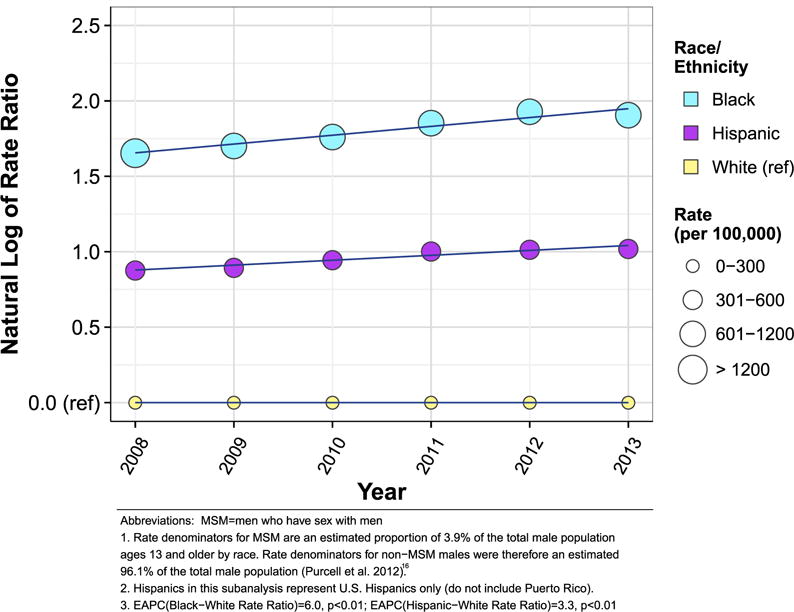

Table 1 shows EAPCs of the Black-White and Hispanic-White relative disparities in new AIDS diagnoses for each of the respective time periods. Black-White disparity increased from 1984 to 1990, followed by the largest increase from 1991 to 1996, and a continued but more gradual increase from 1997 to 2001. After 2002, Black-White disparity began to decrease until 2005. From 2006 to 2013, Black-White disparity significantly rose again, and in 2012 reached the same magnitude as had occurred at the peak of the disparity in 2002. Hispanic-White disparity also significantly increased from 1984 through 1997, though the increase was less compared with the Black-White disparity. After 1998, Hispanic-White disparity decreased slightly through 2013. In addition, rates of AIDS diagnoses increased from 1984 to approximately year 2000 and then decreased through 2013 for all race/ethnicities. Black-White and Hispanic-White disparity trends are presented in Figures 1 and 2. Rate ratios are depicted for ease of interpretation of the disparity measure (Fig. 1). Joinpoint Regression analysis and modeling of EAPCs relied on log-transformed rate ratios (Fig. 2). We present trends in both measures for completeness. Black-White and Hispanic-White rate ratios calculated for this analysis are presented in the Appendix (Table B).

Table 1.

Estimated annual percent change (EAPC) of the rate ratios for the Black-White and Hispanic-White racial/ethnic disparities in AIDS diagnoses, United States and Puerto Rico, 1984–2013

| Disparity | Joinpoint period | Years | EAPC | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black-White | 1 | 1984–1990 | 5.6 | (3.8, 7.5) | <.01 |

| rate ratio | 2 | 1991–1996 | 11.6 | (9.1, 14.1) | <.01 |

| 3 | 1997–2001 | 3.2 | (0.2, 6.3) | .04 | |

| 4 | 2002–2005 | −3.0 | (−7.0, 1.2) | .15 | |

| 5 | 2006–2013 | 1.9 | (0.4, 3.4) | .01 | |

| Hispanic-White | 1 | 1984–1997 | 4.5 | (3.4, 5.6) | <.01 |

| rate ratio | 2 | 1998–2013 | −1.2 | (−2.0, −0.3) | <.01 |

AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; CI, confidence interval; EAPC, estimated annual percent change.

Fig. 1.

Racial/ethnic disparities in new AIDS diagnoses among adults and adolescents, United States and Puerto Rico, 1984–2013.

Fig. 2.

Trends in racial/ethnic disparities of new AIDS diagnoses among adults and adolescents, United States and Puerto Rico, 1984–2013.

EAPCs for the disparities stratified by sex and male-male sexual contact are provided in Table 2. When allowing each subgroup to vary independently in their trend periods, we found that Black-White disparity among males generally followed the trends we observed in Black-White disparity overall. However, Black-White disparity among females increased until 2002, and then remained stable between 2002 and 2013. Hispanic-White disparity for females declined from 2002 to 2013 as observed overall, whereas that for males declined slightly from 2002 to 2005 and then increased from 2006 to 2013. During 2008–2013, Black-White and Hispanic-White disparities significantly increased for men who have sex with men (MSM) and remained stable for men not reporting male-male sex. Figure 3 depicts disparity trends among MSM.

Fig. 3.

Trends in racial/ethnic disparities of new AIDS diagnoses among adult and adolescent men who have sex with men (MSM), United States, 2008–2013.

Discussion

Trends in the Black-White disparity of new AIDS diagnoses were more heterogeneous, with four different inflection points, compared with Hispanic-White disparity trends which changed only once during the epidemic. Racial disparities rose sharply from 1984 to the early 2000s for Blacks and to a lesser extent for Hispanics. Since 1998, Hispanic-White disparity has declined. Black-White disparity declined after 2002, but concerningly, we documented a significant increase from 2006 to 2013. Racial disparities for MSM have increased significantly in recent years. Annual rates of AIDS diagnoses for all racial/ethnic groups increased through year 2000 and have decreased or stabilized from 2000 to 2013. Changes in annual rates of AIDS diagnoses are related ecologically to the introduction of effective ART: the rate of AIDS cases grew in the absence of ART and subsequently declined after ART became more widely available.

Our findings about the overall trends in racial/ethnic disparities of AIDS diagnoses over the past 30 years lead us to hypothesize about factors that may have contributed to the generation, sustainment, and/or decline of these trends. Using AIDS diagnoses as an endpoint is complex because it is impacted by both historical trends in HIV incidence and gaps in one or more HIV care continuum steps. AIDS diagnoses also include people with heterogenous disease progression profiles. For both Blacks and Hispanics, increases in disparities of AIDS diagnoses in the 1980s and 1990s could reflect increasing HIV historical incidence. Yet, because AIDS diagnoses are ultimately an indicator of both HIV infection and failure of effective medical care, increasing disparity trends could also represent rising inequalities in steps of the HIV care continuum during these periods. For example, if Blacks and Hispanics were less likely to test for HIV or had poorer access to health care and HIV services, they may have waited longer to seek care, perhaps until after the onset of AIDS symptoms. From 2002 to 2005, improved access to and uptake of ART and advances in HIV testing (e.g., HIV rapid tests) may have mitigated some barriers to prevention and care that racial/ethnic minority groups had previously experienced.

The increasing trend we observed in the Black-White disparity from 2006 to 2013 likely stemmed from a combination of high HIV incidence among young Black MSM and persistent disparities in the HIV care continuum in recent years [17–19]. Other data have shown that most new HIV diagnoses are occurring among Black MSM, particularly young Black MSM [2,20]. An increase in HIV prevalence from 2008 to 2014 among Black MSM overall and young Black MSM has also been documented [21]. Some of the recent increasing trend we observed may be attributable to increases in HIV diagnoses among young Black MSM if these men are presenting with an AIDS diagnosis at the time of HIV diagnosis or are quickly transitioning to AIDS. This may be true given a high prevalence of late HIV diagnoses within this group [22]. This hypothesis is further supported by our subanalyses demonstrating that Black-White disparities for MSM significantly increased from 2008 to 2013. Among HIV-positive Black MSM, only 75% were estimated to have been diagnosed, 24% retained in care, 20% on antiretroviral therapy, and 16% virally suppressed [17]. Efforts to improve steps of the treatment and prevention cascades including testing and treatment adherence are needed among Blacks overall for whom we have not observed improvements in disparities recently, and with particular emphasis on reaching Black MSM [17], for whom we observed this recent upward disparity trend.

Overall, trends in the Hispanic-White disparity followed similar patterns as the Black-White disparity, but the trend has slowly decreased since 1998. Though Hispanic-White disparities were never as large in magnitude as Black-White disparities, they still represented a substantial 4-fold increase, suggesting care continuum inequalities for Hispanics as well. Hispanics tend to be diagnosed later in the course of their HIV infection compared with Non-Hispanic Whites [23]. Recent studies have also found that Hispanics have higher percentages of linkage to and retention in care, but lower percentages of viral suppression [24]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have reported that 80% of Hispanics living with HIV have been diagnosed, 67% linked to care, 37% retained in care, and 26% virally suppressed—all of which were lower for Hispanics compared with Non-Hispanic Whites [25]. Our subanalyses revealed that Hispanic-White disparity has steadily decreased for females but increased for males from 2006 to 2013. We found significant recent increases in Hispanic-White disparity for MSM from 2008 to 2013, whereas the trend has remained stable for males not reporting male-male sex. This finding indicates that recent Hispanic-White disparity increases in MSM likely drive the increasing trends in males overall, similar to the Black-White disparity. Identifying specific steps of the care continuum such as testing uptake and late HIV diagnosis that uniquely characterize disparities for Hispanics overall and for Hispanic MSM will be important in meeting national goals.

Our study is subject to several limitations. First, we used overall population data and did not analyze trends separately by age, sex, and transmission category over the entire time period of interest. We only considered the disparities stratified by sex and male-male sexual contact over select years, limiting conclusions about changes in trends among subgroups. Unfortunately, we were not able to evaluate these risk groups over the entire study period due to limits in publicly available data and/or lack of annual population denominators. Second, data reported over the 30-year time period varied in many respects and obtaining annual race- and age-specific rates of new AIDS diagnoses required estimating population denominators for several years. Consequently, these estimates were dependent on available U.S. and Puerto Rico census data and additional assumptions presented in the Appendix (Table A). The definition of an AIDS diagnosis changed during the study time period; however, we did not expect these changes to be differential with respect to race/ethnicity. Finally, the reporting of race/ ethnicity in AIDS case reports also likely changed during the time period of interest; this could affect disparity measures if improvements in reporting over time were differential by race. This may have resulted in misclassification of Hispanic ethnicity during earlier years (pre-1997) before the standard two-question format of (1) Hispanic ethnicity and (2) race was widely implemented [26,27]. Options for multiple races are now possible in case reporting and census systems; we included Hispanics of any race and single-race/ethnicity for Non-Hispanic Blacks and Non-Hispanic Whites to avoid potential misclassification of race/ethnicity from this change.

Despite these limitations, our study is the first to demonstrate the contours of racial/ethnic disparities in AIDS diagnoses over the course of the HIV epidemic in the United States and Puerto Rico. Using disparities in AIDS diagnoses as our outcome allowed us to study trends over this 30-year period because AIDS is the only HIV-related outcome that has been consistently reported by surveillance programs since the 1980s. We were able to empirically derive and describe significant trend periods using Joinpoint Regression software, allowing for a more objective view compared with analyses that select intervals based on the most recent decade or similar arbitrary timeframes. Finally, by analyzing AIDS diagnoses, we were able to obtain a high-level understanding of disparities that may be a combined result of multiple gaps in the care continuum and growing racial/ethnic inequalities for high-risk groups such as MSM.

Conclusion

From the beginning of the HIV epidemic, racial/ethnic disparities have been a hallmark of the U.S. epidemic and grew unceasingly from the mid-1980s through the early 2000s. After more than 30 years, we still identify racial/ethnic disparities in HIV-related outcomes, but with different underlying concerns: although AIDS diagnosis rates overall have declined, our data suggest that Blacks and Hispanics in the United States have not benefitted from improved antiretroviral therapies as much as Whites have. Our national strategy reflects the need to address these disparities, but our analysis reveals complexity in how to monitor disparities over time and interpret observed trends. We believe that using AIDS diagnoses as a downstream measure will help to capture changes in racial/ethnic disparities that are collectively a result of the successes or failures of both policies and programs at multiple levels of the care continuum. This should be supplemented with other metrics to assess disparity trends at each step of the HIV care continuum and better understand how certain components may be driving racial/ethnic disparities both overall and specifically for MSM. Incorporating the historical context for racial/ethnic disparities in AIDS diagnoses that we have provided here and pairing this with other indicators specific to care continuum steps will serve as important measures for monitoring NHAS goals to reduce racial/ ethnic disparities in HIV/AIDS.

Acknowledgments

U.S. National Institutes of Health provided funding through grant numbers R01DA038196, R01AI112723, and P30AI050409 (Emory Center for AIDS Research). PSS and JCB conceived the idea for the study. JCB led the data extraction, analysis, and manuscript writing. PSS and ESR contributed to the concept development, analysis, and writing.

The funding source had no role in data analysis or interpretation, manuscript writing, or the decision to submit the manuscript. The corresponding author had full access to the publicly available study data and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Appendix

Table A.

Data characteristics and sources for measuring racial/ethnic disparities* in new AIDS diagnoses, United States and Puerto Rico, 1984–2013

| Years | Race/ethnicity | Numerator(s) | Denominator(s) | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984–1988 | Black, NH | Case counts by race† | CDC annual HIV surveillance reports | |

| White, NH | United States (US): Intercensal state-level population estimates (aggregated) by race and 5-year age groups; intercensal state-level population estimates (aggregated) by single-year age‡ | U.S. Census Bureau | ||

| Hispanic | ||||

| Puerto Rico (PR): Intercensal population estimates by 5-year age group§ | Puerto Rico National Institute of Statistics | |||

| 1989–2007 | Black, NH | Reported (1989–2001)or estimated (2002–2007) rates by race for adults and adolescents (13 + years)║ | CDC annual HIV surveillance reports | |

| White, NH | ||||

| Hispanic | ||||

| 1989–2001: | Reported rates by race for adults and adolescents (13 + years)║ | CDC annual HIV surveillance reports | ||

| 2002–2007: | Estimated case counts¶ | US: intercensal population estimates by race and single-year age# | CDC annual HIV surveillance reports | |

| PR: intercensal population estimates by single-year age# | U.S. Census Bureau | |||

| 2008–2013 | Black, NH | Estimated case counts by race | CDC annual HIV surveillance reports | |

| White, NH | US (2008–2009): Intercensal population estimates by race and single-year age# | U.S. Census Bureau (American Fact Finder) | ||

| Hispanic | ||||

| PR (2008–2009): Intercensal population estimates by single-year age# | ||||

| US (2010–2013): Postcensal population estimates by race and single-year age** | ||||

| PR (2010–2013): Postcensal population estimates by single-year age** | ||||

NH, Non-Hispanic; US, United States; PR, Puerto Rico; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Example calculation for annual Black-White disparity from 1989–2007:

Black – White rate ratio = Reported rate per 100,000 for Blacks/Reported rate per 100,000 for Whites.

Only cumulative case counts by race for adults and adolescents were available for these years. Therefore, a given year’s case count was calculated by subtracting the previous year’s cumulative case count, and this was done for each racial/ethnic group.

For 1984–1998, U.S. intercensal aggregated state-level population estimates stratified by both race and 5-year age groups were publicly available. The same census data were available by single-year age, but not additionally stratified by race. Therefore, we applied the racial distribution for the 10- to 14-year-old age group to the single-year population estimates for 13 and 14 year olds. We then added these to the population estimates by race for adults 15 years of age or older to include adults and adolescents 13 years of age and older in the estimate of our rate denominators for these years.

For 1984–1988 Puerto Rico estimates, only 5-year age groups were reported, therefore the 10- to 14-year-old group was multiplied by 2/5 to estimate the number of 13–14 year olds and include in our population denominator. All population estimates and case counts for Puerto Rico were considered of Hispanic ethnicity.

CDC annual surveillance reports used postcensal data for the calculation of denominators for reporting rates by race.

For years 2002–2007, to calculate rates for Hispanics, case counts reported in the HIV surveillance report for U.S. Hispanics were summed with case counts for Puerto Rico. The only case counts reported for Puerto Rico for these years included both adults and children, therefore we needed to subtract out new AIDS diagnoses among children each year. We used a given year’s cumulative case count data for children and subtracted the previous year’s cumulative case count for children to calculate the number of cases among children each year. We then subtracted this number from the total new AIDS diagnoses reported for Puerto Rico in that year to obtain the Puerto Rico case count among adults and adolescents for that given year.

For 2002–2009, United States and Puerto Rico population estimates for these years were available by race and single-year age to include race-specific population estimates for adults and adolescents 13 years of age and older. Intercensal estimates were used due to availability and to remain consistent with previous years when population denominators required estimation (1984–1988).

For years 2010–2013, only postcensal data were available for midyear population estimates.

Table B.

Calculated rate ratios for the Black-White and Hispanic-White racial/ethnic disparities in AIDS diagnoses, United States and Puerto Rico, 1984–2013

| Disparity | Years, rates, and rate ratios*

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | |

| Black rate | 5.3 | 9.3 | 14.5 | 23.5 | 41.5 | 44.4 | 53.8 | 58.5 | 66.6 | 162.2 |

| Hispanic rate | 4.3 | 6.9 | 11.0 | 15.1 | 30.2 | 34.9 | 42.0 | 41.5 | 39.5 | 89.5 |

| White rate | 1.8 | 3.2 | 5.1 | 8.1 | 11.3 | 11.8 | 14.0 | 14.2 | 14.1 | 30.2 |

| Black-White rate ratio | 3.0 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 4.7 | 5.4 |

| Hispanic-White rate ratio | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 3.0 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Black rate | 129.8 | 119.7 | 115.3 | 107.2 | 84.7 | 84.2 | 74.2 | 76.3 | 76.4 | 75.2 |

| Hispanic rate | 68.2 | 61.9 | 55.8 | 50.6 | 37.8 | 34.6 | 30.4 | 28.0 | 25.7 | 27.1 |

| White rate | 20.8 | 18.5 | 16.2 | 12.4 | 9.9 | 9.0 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 7.0 | 7.2 |

| Black-White rate ratio | 6.2 | 6.5 | 7.1 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 9.7 | 10.9 | 10.4 |

| Hispanic-White rate ratio | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 4.1 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 3.8 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Black rate | 72.1 | 68.7 | 60.3 | 59.2 | 61.0 | 55.1 | 52.7 | 51.3 | 44.8 | 41.3 |

| Hispanic rate | 25.3 | 24.7 | 21.3 | 20.6 | 20.2 | 18.6 | 17.5 | 16.3 | 13.4 | 13.1 |

| White rate | 7.1 | 6.9 | 6.4 | 6.1 | 6.3 | 5.6 | 5.2 | 4.9 | 4.1 | 4.0 |

| Black-White rate ratio | 10.2 | 10.0 | 9.4 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 9.8 | 10.1 | 10.5 | 11.0 | 10.4 |

| Hispanic-White rate ratio | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 |

Rate ratios were calculated with unrounded race-specific rate values; rounded rates and rate ratios are presented.

Footnotes

All authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

The authors have no conflicts of interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas—2012. HIV Surveill Suppl Rep. 2014;19(3):8–28. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/surveillance_report_vol_19_no_3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Fact Sheet: HIV among Gay and Bisexual Men. 2015 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/cdc-msm-508.pdf.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated incidence of AIDS and deaths of persons with AIDS. HIV/AIDS Surveill Rep. 1997;9:7. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/pastIssues.html#panel0. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the United States: At A Glance. 2014 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_basics_ataglance_factsheet.pdf.

- 5.The White House Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States. 2010 Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/NHAS.pdf.

- 6.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020-HIV. 2010 Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/hiv.

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Today’s HIV/AIDS Epidemic. 2014 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/hivfactsheets/todaysepidemic-508.pdf.

- 8.Trends in HIV/AIDS diagnoses—33 states, 2001–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(45):1149–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.An Q, Prejean J, Hall HI. Racial disparity in U.S. diagnoses of acquired immune deficiency syndrome, 2000–2009. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(5):461–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gulick RM, Mellors JW, Havlir D, et al. Treatment with indinavir, zidovudine, and lamivudine in adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection and prior antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(11):734–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammer SM, Squires KE, Hughes MD, et al. A controlled trial of two nucleoside analogues plus indinavir in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection and CD4 cell counts of 200 per cubic millimeter or less. AIDS Clinical Trials Group 320 Study Team. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(11):725–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in HIV Infection Stage 3 AIDS Slideset. 2015 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/hivfactsheets/todaysepidemic-508.pdf.

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Reports. 2015 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/.

- 14.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for Joinpoint Regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Cancer Institute. Joinpoint Regression Program. 2015 Available at: http://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/.

- 16.Purcell DW, Johnson CH, Lansky A, et al. Estimating the population size of men who have sex with men in the United States to obtain HIV and syphilis rates. Open AIDS J. 2012;6:98–107. doi: 10.2174/1874613601206010098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg ES, Millett GA, Sullivan PS, Del Rio C, Curran JW. Understanding the HIV disparities between black and white men who have sex with men in the USA using the HIV care continuum: a modeling study. Lancet HIV. 2014;1(3):e112–8. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(14)00011-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, et al. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):341–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60899-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacKellar DA, Gallagher KM, Finlayson T, Sanchez T, Lansky A, Sullivan PS. Surveillance of HIV risk and prevention behaviors of men who have sex with men—a national application of venue-based, time-space sampling. Public Health Rep. 2007;122:39–47. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Fact Sheet: HIV among Gay and Bisexual Men. 2014 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/CDC-MSM-508pdf.

- 21.Wejnert C, Hess KL, Rose CE, Balaji A, Smith JC, Paz-Bailey G. Age-specific race and ethnicity disparities in HIV infection and awareness among men who have sex with men-20 US Cities, 2008–2014. J Infect Dis. 2016;213(5):776–83. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas—2011. HIV Surveill Rep. 2013;23:5–38. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen NE, Gallant JE, Page KR. A systematic review of HIV/AIDS survival and delayed diagnosis among Hispanics in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(1):65–81. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9497-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gant Z, Bradley H, Hu X, Skarbinski J, Hall HI, Lansky A. Hispanics or Latinos living with diagnosed HIV: progress along the continuum of HIV care—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(40):886–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC. Fact Sheet—HIV in the United States: The Stages of Care. 2012 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/research_mmp_stagesofcare.pdf.

- 26.Office of Management and Budget. Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. 1997 Available at: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/omb/fedreg_1997standards.

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas—2012. HIV Surveill Rep. 2014;24:14–33. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/. [Google Scholar]