Abstract

Objective

To determine the prevalence and associated features of demoralization in Parkinson disease (PD).

Methods

Participants with PD and controls were prospectively recruited from outpatient movement disorder clinics and the community. Demoralization was defined as scoring positively on the Diagnostic Criteria for Psychosomatic Research, Demoralization questionnaire or Kissane Demoralization Scale score ≥24. Depression was defined as Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score ≥10. Forward stepwise logistic regression was used to determine the odds of having demoralization in the overall, control, and PD cohorts.

Results

Demoralization occurred in 18.1% of 94 participants with PD and 8.1% of 86 control participants (p = 0.05). These 2 groups were otherwise comparable in age, sex, education, economics, race, and marital status. Although demoralization was highly associated with depression, there were individuals with one and not the other. Among participants with PD, 7 of 19 (36.8%) depressed individuals were not demoralized, and 5 of 17 (29.4%) demoralized individuals were not depressed. In the overall cohort, having PD (odds ratio 2.60, 95% confidence interval 1.00–6.80, p = 0.051) was associated with demoralization, along with younger age and not currently being married. In the PD cohort, younger age and Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale, part III score (per score 1) were associated with demoralization (odds ratio 1.06, 95% confidence interval 1.01–1.12, p = 0.02).

Conclusions

Demoralization is common in PD and is associated with motor dysfunction. In demoralization, there is a prominent inability to cope, making it somewhat distinct from depression. Treatment approaches are also different, making it important to identify demoralization in patients with PD.

Demoralization is a psychological state characterized by helplessness, hopelessness, and a sense of failure.1 The clinical hallmark of demoralization is subjective incompetence, a self-perceived incapacity to perform tasks appropriate in stressful situations.2 Although demoralization co-occurs with depression, the two are distinct. In depression, the appropriate course of action is known, yet there is decreased motivation. Alternatively, in demoralization, there is prominent uncertainty as to the appropriate course of action. Demoralization occurs in chronic diseases such as cancer and congestive heart failure.3

Parkinson disease (PD) is a chronic neurologic disorder, highly comorbid with depression. Patients with PD are at heightened risk for demoralization; however, demoralization has not been researched in PD. We aimed to determine the prevalence of demoralization in patients with PD and age-sex matched controls and to identify clinical correlates of demoralization in PD.

Methods

Participants

Consecutive patients with PD were recruited from the Movement Disorders Clinic (of A.P.) at Yale-New Haven Hospital, a private health care system, between June 2016 and May 2017. Control participants were frequency matched on age and sex to patients and were recruited during local senior center visits and by contacting people in the Yale Research Studies Registry, a registry of persons interested in research participation. Potential participants were told that the study aimed to assess the mental state in adults. Inclusion criteria were age of 40 to 90 years and English comprehension/literacy. Exclusion criteria included substance abuse, history of dementia, and terminal illness. Thirty-eight participants with PD who declined participation (not interested) had similar age and sex but were more likely in Hoehn and Yahr stage III or IV than control participants (39.5% vs 11.5%, p = 0.0002). Participants were diagnosed with PD by a movement disorders neurologist (A.P.) using UK Brain Bank Society criteria.4 Questionnaires were administered to all participants in person by trained research assistants after the clinic appointment. Participants provided written informed consent approved by the Yale University Ethics Board.

Demoralization and depression assessment

Demoralization was assessed with gold standard questionnaires: the Diagnostic Criteria for Psychosomatic Research, Demoralization (DCPR-D)5 and Kissane Demoralization Scale (KDS).6 DCPR-D consists of 4 questions: (1) Do you feel that you have failed to meet your expectations or those of other people? (2) Do you feel that you are unable to cope with pressing problems? (3) Do you experience feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, or giving up? (4) Have these feelings been present for 1 month or longer? Demoralization was defined as positive responses to questions 3 and 4 and to either question 1 or 2.5 KDS contains 24 items that assess the frequency over the past 2 weeks that participants have had specific feelings (0–4; never to all the time) such as “I feel hopeless” and “No one can help me.” Demoralization was defined as KDS score ≥24 (overall cohort mean plus 1 SD as previously used).6 Overall, demoralization was defined as KDS score ≥24 or positive DCPR-D (as outlined above). Depression was assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ9), which scores all 9 DSM depression criteria as 0 to 3 (not at all to nearly every day); depression was defined as PHQ9 score ≥10.7

PD-related measures

The Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire-8 assesses health-related quality of life in PD8 using 8 questions measuring frequency in the last month of difficulty with activities of daily living, cognition, or mood. One investigator (A.P.) assessed motor function in PD using the revised Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale, part III (UPDRS-m)9; 18 items such as speech, finger tapping, and posture are rated on a 0 to 4 scale of difficulty. Patients were classified (by A.P.) by Hoehn and Yahr stage.

Statistical analysis

Sample size was calculated on the basis of a demoralization estimate of 20% in PD and 5% in the general population,10 requiring a sample size of 75 in each group. Characteristics were compared between the PD and control groups with χ2 (categorical variables) and Student t tests (continuous variables). Logistic regression was used to determine the odds of demoralization in the overall, control, and PD cohorts separately. Forward stepwise regression was used, and potential confounding variables were entered into the final model on the basis of their association in separate bivariate analysis (p ≤ 0.10) with demoralization odds. Statistical analysis was performed with the R statistical package 3.3.2 (Auckland, New Zealand).

Data availability

Anonymized data will be shared on request with any qualified investigator.

Results

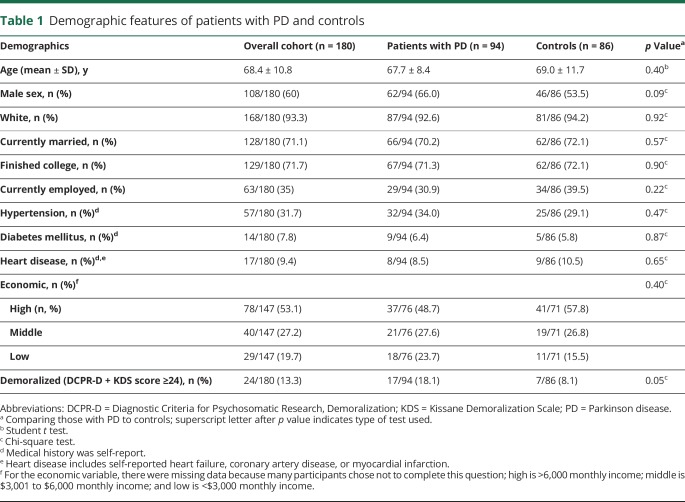

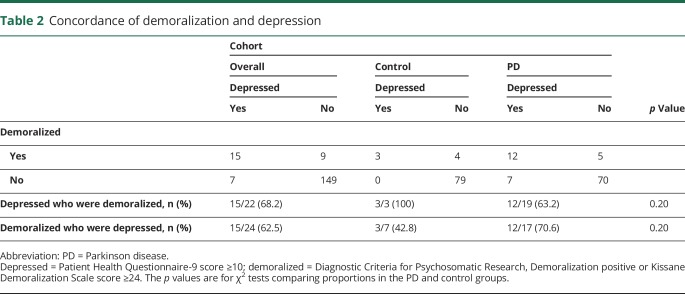

Ninety-four participants with PD (62 men, 66.0%) and 86 controls (46 men, 53.5%) enrolled during the 1-year period. The PD and control groups were comparable for age, sex, race, marital status, education, employment, economic status, and medical comorbid conditions (table 1). There was a higher prevalence of demoralization in the PD than the control group. Seventeen of 94 participants with PD were demoralized vs 7 of 86 controls (18.1% vs 8.1%, p = 0.05). Demoralization was highly associated with depression (p < 0.0001), but imperfectly. In the entire cohort, among demoralized individuals, 62.5% were depressed, and among depressed individuals, 68.2% were demoralized. There seemed to be greater depression-demoralization discordance in the PD than the control group, in which demoralized individuals were more likely depressed and depressed individuals were less likely demoralized (although these differences were not statistically significant) (table 2). In the PD group, 19 of 94 participants were depressed compared to 3 of 86 control participants (20.2% vs 3.5%, p = 0.0006). There were significantly more comorbid depressed-demoralized individuals in the PD than control group (12.8% vs 3.5%, p = 0.01).

Table 1.

Demographic features of patients with PD and controls

Table 2.

Concordance of demoralization and depression

Within the PD group, 85 participants (88.5%) were in Hoehn and Yahr stage I or II and 9 were in stage III or IV; Hoehn and Yahr staging was not associated with demoralization (data not shown). UPDRS-m score was recorded in 83 participants with PD; 71 were “on,” 9 “off,” and 3 were not on PD medication. Demoralized compared to nondemoralized participants with PD had significantly higher UPDRS-m scores (30.7 ± 11.3 vs 23.6 ± 11.7, p = 0.04), higher mean PHQ9 scores (12.6 ± 5.7 vs 4.1 ± 3.3, p < 0.0001), and higher mean Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire-8 scores (11.9 ± 5.0 vs 4.5 ± 3.6, p < 0.0001); there was no difference in percentage of those on medications for PD (i.e., levodopa, dopamine agonists).

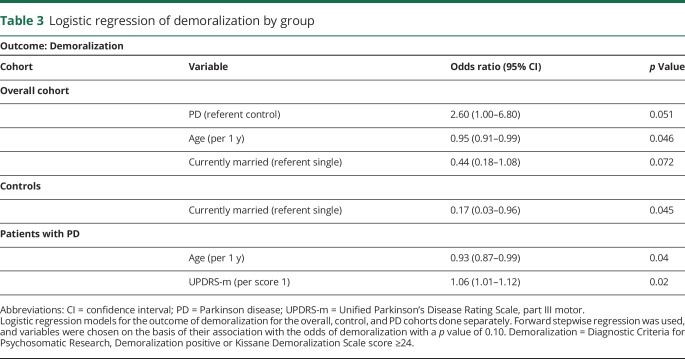

In the overall cohort, logistic regression showed that PD (odds ratio 2.60, 95% confidence interval 1.00–6.80), younger age, and not being married were associated with odds of demoralization (table 3). Among controls, only not being married was associated with demoralization odds. Among participants with PD, younger age and higher UPDRS-m score were associated with odds of demoralization. Adding antidepressant or PD medications into models for the overall or PD cohorts did not appreciably affect results. Logistic regression models for the outcome depression in participants with PD did not reveal any significantly associated factors.

Table 3.

Logistic regression of demoralization by group

Discussion

We introduce the psychological phenomenon of demoralization as it relates to PD. The main finding of our study is that demoralization is common among patients with PD, approaching 20%, which is significantly more frequent than in age- and sex-matched individuals. In the PD cohort, demoralization was independent of sex, education, marital status, and economic status but was associated with younger age and motor dysfunction. While demoralization was highly correlated to depression, there was discordance between depression and demoralization, most obvious in the PD cohort. Demoralized individuals without depression were present in both the PD and control groups; however, depressed individuals without demoralization were present only in the PD group. Perhaps more important, comorbid demoralization and depression were far more common among participants with PD (12.8% vs 3.5%).

In participants with PD, demoralization but not depression was associated with motor dysfunction, suggesting that demoralization more than depression is tied to functionality. Discordance in the presence of demoralization and depression suggests that demoralization is not a simple marker of depression. It has been suggested that demoralization is better treated with cognitive behavioral therapy to address a pathologic way of thinking, rather than antidepressant medication, so distinguishing these entities is important to direct therapy. From this study, it is not clear whether demoralization results from psychological stressors that differ from those that result in depression and furthermore whether clinical or social consequences of demoralization differ from those of depression. Limitations of this study include the cross-sectional design and a lack of information regarding details of employment. In addition, patients with PD with severe disease were more likely to have declined participation; hence, we likely underestimated the prevalence of demoralization. A longitudinal study design, expanded detail in psychosocial history elements, and inclusion of patients with later-stage PD will be important to disentangle the relationships among PD, demoralization, and depression.

Glossary

- DCPR-D

Diagnostic Criteria for Psychosomatic Research, Demoralization

- DSM

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- KDS

Kissane Demoralization Scale

- PHQ9

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

- UPDSR-m

Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale, part III

Author contributions

B.B. Koo is the primary investigator and author. His contributions included developing the hypothesis, formulating the analyses, interpreting the data output, writing the manuscript, performing the statistical analysis, and making all tables/figures. C.A. Chow contributed with protocol writing, participant recruitment, data collection, interpreting the data, writing and editing the manuscript. D.R. Shah and F.H. Khan contributed with participant recruitment, writing and editing the manuscript. B. Steinberg contributed with participant recruitment, data collection, inputting data, writing and editing the manuscript. D. Derlein contributed with participant recruitment, data input, writing and editing the manuscript. K. Nalamada contributed with participant recruitment, data input, statistical analysis, writing and editing the manuscript. K.S. Para and V.M. Kakade contributed with participant recruitment, data input, writing and editing the manuscript. A.S. Patel contributed with participant recruitment, performing the UPDRS-m scoring, and writing and editing the manuscript. J.M. de Figueiredo contributed by helping to develop the hypothesis, collecting the demoralization questionnaires to use, formulating the analyses, interpreting the data output, writing and editing the manuscript. E.D. Louis contributed by helping to develop the hypothesis, formulating the analyses, interpreting the data output, writing and editing the manuscript.

Study funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

B. Koo, C. Chow, D. Shah, F. Khan, B. Steinberg, D. Derlein, K. Nalamada, K. Para, V. Kakade, A. Patel, and J. de Figueiredo report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. E. Louis has received research support from the NIH: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) No. R01 NS094607 (principal investigator), NINDS No. R01 NS085136 (principal investigator), NINDS No. R01 NS073872 (principal investigator), NINDS No. R01 NS085136 (principal investigator), and NINDS No. R01 NS088257 (principal investigator). He has also received support from the Claire O'Neil Essential Tremor Research Fund (Yale University). Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Tecuta L, Tomba E, Grandi S, Fava GA. Demoralization: a systematic review on its clinical characterization. Psychol Med 2014;45:673–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Figueiredo JM, Frank JD. Subjective incompetence, the clinical hallmark of demoralization. Compr Psychiatry 1982;23:353–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mangelli L, Fava GA, Grandi S, et al. Assessing demoralization and depression in the setting of medical disease. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:391–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, Lees AJ. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992;55:181–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fava GA, Freyberger HJ, Bech P, et al. Diagnostic criteria for use in psychosomatic research. Psychother Psychosom 1995;63:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kissane DW, Wein S, Love A, Lee XQ, Kee PL, Clarke DM. The Demoralization Scale: a report of its development and preliminary validation. J Palliat Care 2005;20:269–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, Peto V, Greenhall R, Hyman N. The PDQ-8: development and validation of a short-form Parkinson's disease questionnaire. Psychol Health 1997;12:805–814. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goetz CG, Fahn S, Martinez-Martin P, et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): process, format, and clinimetric testing plan. Mov Disord 2006;22:41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mangelli L, Semprini F, Sirri L, Fava GA, Sonino N. Use of the Diagnostic Criteria for Psychosomatic Research (DCPR) in a community sample. Psychosomatics 2006;47:143–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be shared on request with any qualified investigator.