Abstract

Purpose

Patients often complain of change of defecation pattern and it is necessary to quantify their symptoms. To quantify symptoms, use of questionnaire is ideal, so we adopted a simple and easily writable visual analogue scale for irritable bowel syndrome questionnaire (VAS-IBS). The aim of this study was to develop and validate the Korean version of VAS-IBS questionnaire (Korean VAS-IBS) that can adequately reflect the defecation pattern.

Methods

This study translated English VAS-IBS into Korean using the forward-and-back translation method. Korean VAS-IBS was performed on 30 patients, who visited the outpatient clinic and had no possibility of special defecation pattern. Detailed past medical history and Bristol stool chart was added to the questionnaire. The survey was conducted twice, and the median interval between the 2 surveys was 10 days (8–11 days). Cronbach α for internal consistency reliability and intraclass correlation coefficients for test-retest reliability were analyzed.

Results

Korean VAS-IBS achieved acceptable homogeneity with a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.66–0.79 showing adequate internal consistency reliability. In addition, intraclass correlation coefficients showed significant test-retest reliability with 0.46–0.80 except for the question assessing the “perception of psychological wellbeing.”

Conclusion

The Korean VAS-IBS is a valid and reliable questionnaire for the measurement of the symptoms of defecation pattern changes.

Keywords: Surveys and questionnaire, Defecation, Visual analog scale, Translations

INTRODUCTION

Some people experience a defecation pattern change even if they are not the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients. In particular, some people experience a defecation pattern change before or after a particular event (gastrointestinal [GI] surgery, GI malignancy, colonoscopic evaluation, ingestion of poisoned foods, taking unspecified medicine) [1,2,3]. It is also a major complaint by the patients and in which patients want immediate improvement. Patients who visit the outpatient clinic with a defecation pattern change as the chief complaint requests symptomatic treatments, however, they are often medically within normal or have other problems [2]. In such cases, it is difficult to understand how “uncomfortable” the patient feels. If we can quantify how the defecation pattern changes with time, this can be helpful in identifying the patient's condition and to determine whether to treat [3]. Tools are needed to measure their degree of symptom change with ease.

Since discomfort associated with the defecation pattern is subjective, it is reasonable to use a questionnaire to digitize the patient's subjective discomfort and the degree of change [4]. Therefore, we decided to study the defecation pattern through a questionnaire and to apply a previously developed questionnaire for our purpose. Because the majority of previously developed questionnaires were based on IBS patients, we selected the Visual Analogue Scale for Irritable Bowel Syndrome questionnaire (VAS-IBS) among them, which is the most appropriate questionnaire for this study. The English version of VAS-IBS (English VAS-IBS) was selected based on its simplicity, short necessary time, and capability to intuitively assess the defecation pattern changes [5]. The questionnaire was originally developed to assess the severity of IBS or chronic constipation, not a diagnosis, however, this study was designed to assess the defecation pattern [6].

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to translate the English VAS-IBS into Korean and to validate the questionnaire to assess whether the questionnaire adequately reflects the defecation pattern change of the participant.

METHODS

Selection of questionnaire

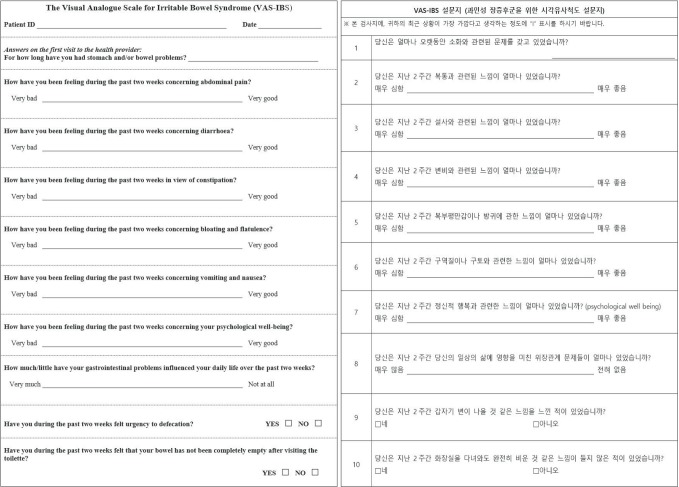

There are several questionnaires developed to evaluate the degree of symptomatic of digestive system. They are mainly related to upper GI tract symptoms [7], or are mainly questionnaires developed for the diagnosis of IBS or chronic constipation [8], or questionnaires which were developed to evaluate the quality of life after surgery [9]. Among these, the requirement of a questionnaire to identify defecation pattern change was as follows; (1) The time required for the questionnaire should be short. (2) A universal and accurate word should be used so that both participants and the researchers can easily understand the contents questionnaire. (3) The degree of subjective symptoms should be expressed intuitively and can be scored. (4) It should be possible to evaluate changes in the defecation pattern by comparing multiple consecutive questionnaire scores. As a questionnaire meeting the above requirements, we adopted the VAS-IBS developed in Sweden in 2007. It is a questionnaire composed of 10 questions made in Swedish so that IBS patients could easily express their symptoms [4,5]. In order to better reflect the subjective feelings of participants, 5 items related to abdominal symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, bloating and flatulence and flatulence, nausea and vomiting, and psychological well-being and 2 items related to daily life influenced GI problems and psychological health were included with the assessment by the VAS. The questionnaire items on the VAS indicated the symptom severity on a 10-cm horizontal line, and the most left point indicated “very bad” and the most right point indicated “very good.” The most left point corresponds to a 0 point and the most right point to 100 points according to the length.

The study added a Bristol stool chart to deal with defecation shapes not included in the VAS-IBS questionnaire and also a question asking the frequency of defecation. The Bristol stool chart was originally developed to estimate the bowel transit time and is a single item scale that can be evaluated for inclusion, which can help identify defecation pattern [10]. The frequency of defecation should be recorded after the question, “how many times a day” and “how many days per once” by the participants.

In addition, to ensure the validity of the questionnaire, we collected the clinical characteristics of the participants of the questionnaire. Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, thyroid disease, disorder of central nervous system, neuropsychiatric disease, previous cancer history, operation history of GI tract, history of anal disease, IBS, functional GI disorder, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and previous medication history, which are the underlying diseases that may affect the defecation pattern, were included in the survey items.

Translation of questionnaire

The Korean VAS-IBS was translated using the English VASIBS [5]. The original author, Lund University, Ph.D. Mariette Bengtsson allowed this translation before this study began. The translation from English to Korean was made using the forward and back translation method [11,12]. The translation was focused on whether the questions are being understood at the same level in each language. Two Korean-English bilingual translators translated the questionnaires from English to Korean, respectively, and made 2 versions of translation (forward translation). One of them was adopted by the researcher (reconciled single target language translation). Another bilingual translator translated this Korean VAS-IBS into English (back translation). These three Korean-bilingual translators and the researcher compared the English VAS-IBS version and revised the Korean translation (back translation review). This Korean translation has been reviewed by a Korean linguist to revise the Korean language of the questionnaire (expert review). To prevent inadvertent comprehension of the translation results, the staffs at the Center for Colorectal Cancer and the researchers confirmed the semantic problems (prefinalization review). The prefinalization review process included a pretesting process involving 11 individuals, as the World Health Organization recommends prefinalization review by minimum 10 individuals. All of them were over 18 years old, 5 males and 6 females. Cognitive interviewing was performed. Finally, the researchers decided on the final translation considering all the revisions and comments (final version). As it is the first version of the Korean VAS-IBS, we aimed to translate the English VAS-IBS questionnaire without modification of their contents and thus translated it with forward and backward translation methodology. The confirmed Korean VAS-IBS is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. English and Korean versions of the Visual Analogue Scale for Irritable Bowel Syndrome (VAS-IBS) questionnaire.

Subjects and filling out the Korean VAS-IBS

The inclusion criteria of this study are as follows. Those individuals that have visited National Cancer Center from November to December 2016 for routine health screening and (1) were not IBS patients, (2) had no history of GI cancer or GI surgery, (3) those who did not take medications such as dementia medication or mood disorder medication that can affect defecation (4) had no plans to receive colonoscopy before and after the questionnaire (because a defecation pattern change can occur before and after colonoscopy). A prospective questionnaire study was conducted on 30 patients who did not have defecation problem or visited for routine health checkup but did not undergo colonoscopy. All participants enrolled in this prospective study did not receive colonoscopy within the previous 6 months and did not undergo colonoscopy during the course of this study.

Thirty participants were registered and interviewed at the visit. The first questionnaire was completed at the time of enrollment, and the second questionnaire was done median 10 days after the first questionnaire (8–11 days). Informed consent was obtained prior to the study.

Originally, the questionnaire was designed for IBS patients, however we validated the questionnaire with healthy participants. The researcher and assistant researchers assisted the participants to answer the Korean VAS-IBS at the first visit. To encourage the participation of the follow-up (2nd) questionnaire, a small gift (plastic tumbler or nail clipper set) worth about $3 to $4 was provided to the participant after the receival of the first questionnaire. Because the questionnaire was a VAS, telephone questionnaires were not possible and we either mailed the written questionnaire or had them fill out when they revisited the outpatient clinic.

Statistics

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Cancer Center, Korea (approval number: NCC2016-0260) and funded by prize money for research of the Career Development Award of this institution. The VAS-IBS is a questionnaire in which each item assesses individual symptoms. Therefore, when conducting two questionnaires over time and comparing scores, one should compare scores for individual item rather than adding the results of the questionnaire. The main comparisons were made with second to eighth question of VAS-IBS, which were directly related to abdominal symptoms and evaluated “abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, bloating and flatulence, nausea and vomiting, psychological well-being, influenced daily life.”

Baseline characteristics of participants were presented as median (range) for continuous variables and frequency (percentages) for categorical variables. The statistical analysis of this study was to examine the internal consistency reliability and test-retest reliability. The internal consistency reliability is a measure of the homogeneity of the items in the VAS-IBS and is expressed as the Cronbach alpha coefficient. Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.7 to 0.9 is considered as showing “good” reliability [13,14].

Test-retest reliability is a statistical technique that evaluates the reproducibility of the questionnaire, that is, whether the participants will have the same results on the same condition for the same questionnaire is evaluated. Test-retest reliability was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). The ICC value is fair when the value exceeds 0.40, and has a high correlation with more than 0.70 and converging to 1 [15]. P-values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. All results were analyzed using SAS ver. 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and R ver. 3.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Subjects and filling out the Korean VAS-IBS

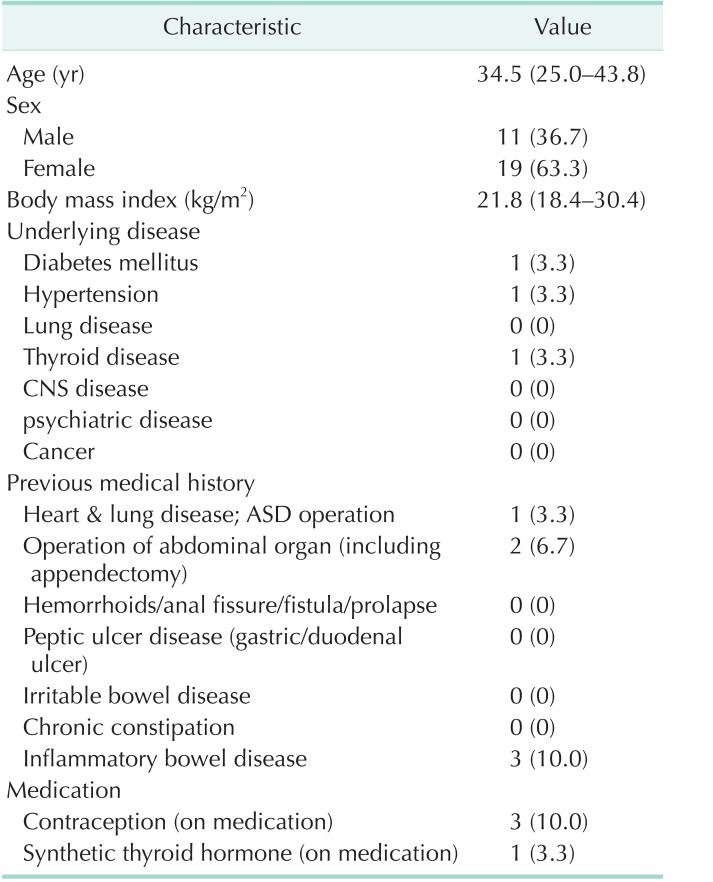

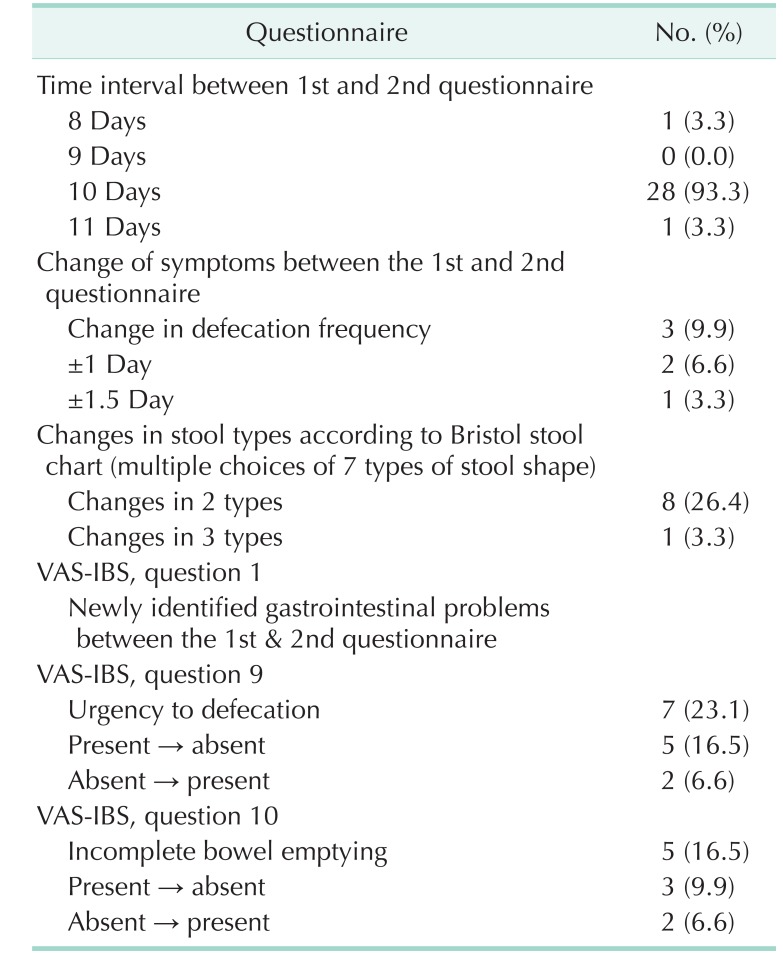

In the first questionnaire study, the researchers directly met the participants in a face-to-face interview format. The second study was conducted when the participants visited the next visit (28 persons) or by mail (2 persons). Between the first and second questionnaires, no cases were excluded from the study. The baseline characteristics of this study are shown in Table 1. The median of age was 34.5 years and 19 (63.3%) were women. There were 3 patients with history of IBD, 3 patients taking oral contraceptives over the study period, 1 patient taking synthetic thyroid hormone and there was no other patients with chronic constipations or IBS. However, IBD patients have been treated in the past and have remained stable without medications in recent years. There were three participants who expressed GI symptom changes when comparing the responses for the first question of the Korean VAS-IBS between the first and the second questionnaires. However, none of the participants mentioned that there was a significant change in the frequency of defecations. When comparing the Bristol stool chart responses between the first and second questionnaires, only one patient expressed a difference of stool shape change more than 3 levels (Table 2).

Table 1. Characteristics of participants (n = 30).

Values are presented as median (range) or number (%).

CNS, central nervous system; ASD, atrial septal defect.

Table 2. Change between first and second questionnaire.

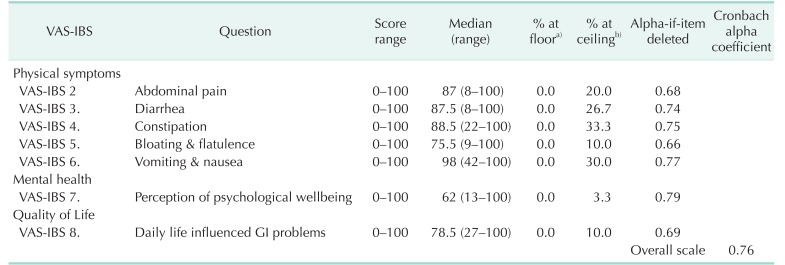

Internal consistency reliability

Table 3 shows the floor effects, the ceiling effects and the skewness of each item in the final version of the Korean VAS-IBS of the study participants. Median values of each symptom ranged from 6 to 98 points. Cronbach alpha coefficient was 0.76, indicating that the overall scale of the Korean VAS-IBS showed a high internal consistency reliability. The alpha-if-item deleted value of the seven VAS items also show 0.66 to 0.79, which also shows high reliability among items (Table 3).

Table 3. The score range, mean as well as floor and ceiling effects and skewness of each item in the Korean version of as VAS-IBS questionnaire & internal consistency of the VAS-IBS (Cronbach alpha).

VAS-IBS, visual analogue scale for irritable bowel syndrome questionnaire; GI, gastrointestinal.

a)% at floor: percentage of respondents at the lowest possible scale score. b)% at ceiling: percentage of respondents at the highest possible scale score.

Test-retest reliability

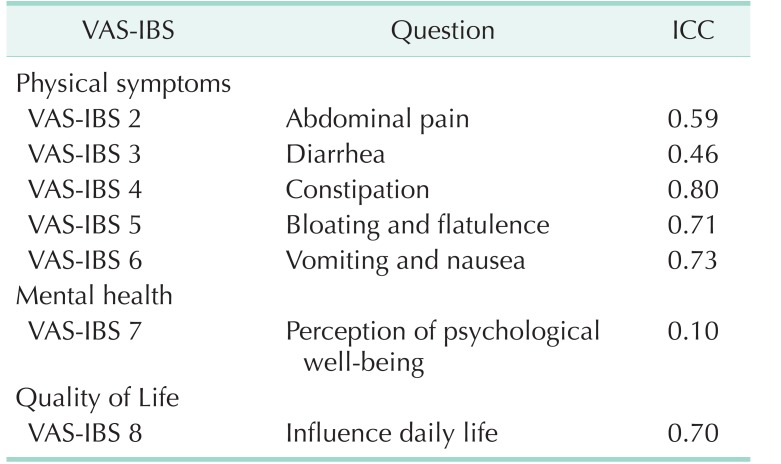

The test-retest reliability of the Korean VAS-IBS was estimated through ICC. Each item showed ICC ranging from 0.46 to 0.80 except for the question that assessed the “perception of psychological well-being.” This question showed an ICC of 0.1. This means that the participants marked conflicting scores between the first and second surveys. The “abdominal pain” (0.59) and “diarrhea” (0.46) showed relatively fair correlation, while “constipation” (0.80) showed the best correlation. Other items such as “bloating and flatulence,” “vomiting and nausea,” and “constipation” showed a high correlation of more than 0.7 (Table 4).

Table 4. Test-retest reliability.

VAS-IBS, visual analogue scale for irritable bowel syndrome questionnaire; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficients.

Other aspects

Seven participants answered that there was a change in “urgency to defecation” (VAS-IBS No. 9) between the first and second questionnaire, and five answered “incomplete bowel emptying” (VAS-IBS No. 10) respectively. However, none of them mentioned changes in the number of defecations. Four of the 7 respondents who reported a change in urgency to defecation (VAS-IBS No. 9) mentioned changes in the Bristol stool chart with 2 level difference (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

This study was planned as a preliminary step to investigate how much defecation pattern change actually is affected by colonoscopy. Until now, there has been no proven method to systematically measure defecation pattern changes before and after colonoscopy, so the questionnaire should be able to evaluate the defecation pattern at a particular point and to easily identify the defecation pattern change. The final questionnaire candidates considered in the study were Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale - Irritable Bowel Syndrome (GSRS-IBS), Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) score, and VAS-IBS [7,9,16]. Among these, MSKCC score is a questionnaire consisting 18 questions, developed in 2005 to evaluate the bowel function after sphincter preserving surgery in rectal cancer patients, and the symptom level was divided into five sections for each question assessing a symptom [9]. However, this questionnaire was excluded because it was a questionnaire to evaluate bowel symptoms related to sphincter preservation. The GSRS-IBS is a questionnaire on IBS symptoms with a total of 13 questions, developed in 2003, and considered as a questionnaire to be evaluated in this study [16,17]. This used 7 Likert scales from 0 to 7 for each question to express the patient's symptoms. Unlike the VAS-IBS, when the score is assessed on a scale divided into 7 grades, and the symptoms are not clearly distinguished by the score. The score is concentrated in the middle area of 3 to 5 points and is difficult to distinguish which symptom is the most problematic and serious [5]. On the other hand, VAS-IBS can freely check the worst-and-best feeling within a 10-cm length, without being bound to a fixed scale. The number of questions was relatively small, and only one question per symptom was asked, which was easy for the researchers to understand the contents. In addition, it is simple to participants because participants can write everything on just one sheet of paper [4,6,18].

To complement the Korean VAS-IBS, this study added questions included in the Bristol stool chart and the frequency of defecation in order to improve the reliability of the information obtained from the participants' VAS-IBS [19]. In order to verify the test-retest reliability, the questionnaire was conducted twice, the second time about 10 days after the first questionnaire. In the second questionnaire, the Bristol stool chart and the frequency of defecation was additionally included. If there were participants who had newly developed symptoms during the period between the first and the second questionnaires (VAS-IBS No.1), we would predict that this would be true by considering the records of Bristol stool chart and the frequency of defecations. In this study, 2 respondents answered that there was a change in the defecation pattern in the first question of the VAS-IBS, and they recorded a difference of more than 2 grade of Bristol stool chart between the 2 questionnaires. However, the Bristol stool chart has limitations. It was originally developed to estimate the bowel transit time and above all, many of the participants could not recall their recent stool shape. The result of the Bristol stool chart is less reliable unless the defecation pattern was unusual and could be recalled such as constipation or diarrhea. Moreover, the similarity between the choices of answers in the Bristol stool chart also makes the evaluation difficult [10,19,20].

This study included investigations of factors that could affect the patient's defecation pattern: history of digestive tract disease (IBS, IBD, GI tract cancer, operation history of abdominal organ) and chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, psychiatric disorders or medications such as oral contraceptives were investigated [21,22,23]. When analyzing the Korean VAS-IBS of participants with these medical histories, there were no participants with defecation pattern changes during the period between the two questionnaires.

In the Korean VAS-IBS, 7 VAS questions showed satisfactory overall results in terms of internal consistency reliability and test-retest reliability. However, the test-retest reliability, which is the main tool for evaluating the validation of this study, requires additional interpretation. As shown in Table 4, the perception of psychological well-being (VAS-IBS No. 7) is very low with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.10. This means that the participants gave a score oppositely in the 2 questionnaires. The cause of this can be variable for each participant. The original intention of this “perception of psychological well-being” was the “perception of psychological well-being due to the recent defecation pattern.” If participants were aware of this intention and answered the questionnaire consistently in both surveys, the intraclass correlation coefficient of this question would be as high as the other questions. However, the intention is not fully described in the English VAS-IBS. For future studies to assess the defecation patterns after colonoscopy or in other studies, the Korean VAS-IBS should be more descriptive and require addition of the perception of psychological well-being “due to the recent defecation pattern.”

Items not evaluated by the VAS were “stomach and/or bowel problem” (VAS-IBS No. 1), “urgency to defecation” (VAS-IBS 9), “incomplete bowel emptying” (VAS-IBS No. 10). They are open-answer question or “yes or no” questions. For the first question, the “stomach and/or bowel problem” was translated in Korean in intention to assess “the symptomatic problem of overall digestive tract function” but even participants who showed urgency to defecation or incomplete bowel emptying did not answer the first question. This suggests that the first question of the Korean VAS-IBS was not fully understood by the participants. The first question asked the participants “how long” the symptoms last but we asked “from when” the problems were present. The other questions asking the symptoms past 2 weeks were revised at the VAS-IBS interview to ask the symptoms for recent 1–2 days. Revision of the Korean VAS-IBS is required if used as a tool to assess the defecation pattern after colonoscopy in the future.

The English VAS-IBS have been validated and in patients with IBS and showed that this questionnaire can be used as intended [4,5,6]. However, VAS-IBS has not been translated into Korean and also has not been used to assess defecation pattern changes. The Korean VAS-IBS showed good results in internal consistency reliability and test-retest reliability in questions that assessed the defecation pattern. This suggests that it may be used as a tool to analyze the defecation pattern changes generally.

There are a few limitations to this study. First, we have tried to translate the English VAS-IBS in Korean without any modification of the contents or the form. Revision of some of the questions may be necessary in questions with misunderstanding and which are not consistent with the study purpose or study population. Second, this study has been in relatively small number of patients. Therefore, this questionnaire could be a good backbone for the future study, but statistically discriminable value in specific study population and specific topics should be evaluated in near future. Third, since it is based on a VAS, telephone interview was not feasible. However, the receipt of written answers by fax or photo was possible. Fourth, the constipation and diarrhea perceived by the participants are different from the medical definition [24]. However, since we used this tool to analyze the change in subjective symptoms, not the presence of the medical symptoms, the difference in perception may have less effect in this study.

Despite the limitations, this study has strengths in that it was the first study to translate the VAS-IBS in Korean by using the forward and back translation method and validate the questionnaire for evaluating the changes in defecation patterns [11,12].

In conclusion, The Korean VAS-IBS is easy and simple questionnaire that was translated by forward and back translation method. This questionnaire showed good internal consistency reliability and test-retest reliability, that means it is feasible in assessing the changes in defecation pattern. With revisions for some questions according to the study purpose, this questionnaire can be used in other studies or clinical practice.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Center Korea (NCC-1710070, NCC-1810060).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Van Dyke C, Melton LJ., 3rd Epidemiology of colonic symptoms and the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:927–934. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90717-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jun DW, Park HY, Lee OY, Lee HL, Yoon BC, Choi HS, et al. A population-based study on bowel habits in a Korean community: prevalence of functional constipation and self-reported constipation. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:1471–1477. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Melton J, 3rd, Wiltgen C, Zinsmeister AR. A patient questionnaire to identify bowel disease. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:671–674. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-8-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bengtsson M, Ohlsson B, Ulander K. Development and psychometric testing of the Visual Analogue Scale for Irritable Bowel Syndrome (VAS-IBS) BMC Gastroenterol. 2007;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bengtsson M, Persson J, Sjolund K, Ohlsson B. Further validation of the visual analogue scale for irritable bowel syndrome after use in clinical practice. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2013;36:188–198. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0b013e3182945881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bengtsson M, Hammar O, Mandl T, Ohlsson B. Evaluation of gastrointestinal symptoms in different patient groups using the visual analogue scale for irritable bowel syndrome (VAS-IBS) BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:122. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Revicki DA, Wood M, Wiklund I, Crawley J. Reliability and validity of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:75–83. doi: 10.1023/a:1008841022998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song KH, Jung HK, Min BH, Youn YH, Choi KD, Keum BR, et al. Development and validation of the Korean rome III questionnaire for diagnosis of functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;19:509–515. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2013.19.4.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Temple LK, Bacik J, Savatta SG, Gottesman L, Paty PB, Weiser MR, et al. The development of a validated instrument to evaluate bowel function after sphincter-preserving surgery for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1353–1365. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0942-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:920–924. doi: 10.3109/00365529709011203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eremenco SL, Cella D, Arnold BJ. A comprehensive method for the translation and cross-cultural validation of health status questionnaires. Eval Health Prof. 2005;28:212–232. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:3186–3191. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Streiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters GJ. The alpha and the omega of scale reliability and validity: why and how to abandon Cronbach's alpha and the route towards more comprehensive assessment of scale quality. Eur Health Psychol. 2014;16:56–69. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess. 1994;6:284–290. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiklund IK, Fullerton S, Hawkey CJ, Jones RH, Longstreth GF, Mayer EA, et al. An irritable bowel syndrome-specific symptom questionnaire: development and validation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:947–954. doi: 10.1080/00365520310004209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Posserud I, Syrous A, Lindstrom L, Tack J, Abrahamsson H, Simrén M. Altered rectal perception in irritable bowel syndrome is associated with symptom severity. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1113–1123. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlsson AM. Assessment of chronic pain. I. Aspects of the reliability and validity of the visual analogue scale. Pain. 1983;16:87–101. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90088-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao SS, Camilleri M, Hasler WL, Maurer AH, Parkman HP, Saad R, et al. Evaluation of gastrointestinal transit in clinical practice: position paper of the American and European Neurogastroenterology and Motility Societies. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:8–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lane MM, Czyzewski DI, Chumpitazi BP, Shulman RJ. Reliability and validity of a modified Bristol Stool Form Scale for children. J Pediatr. 2011;159:437–441.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monane M, Avorn J, Beers MH, Everitt DE. Anticholinergic drug use and bowel function in nursing home patients. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:633–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, Heaton KW, Irvine EJ, Müller-Lissner SA. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut. 1999;(45 Suppl 2):II43–II47. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamm MA, Farthing MJ, Lennard-Jones JE. Bowel function and transit rate during the menstrual cycle. Gut. 1989;30:605–608. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.5.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johanson JF, Kralstein J. Chronic constipation: a survey of the patient perspective. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:599–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]