Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HVB) infection is a worldwide epidemic that, in addition to the liver, causes damage in other organs. HBV-membranous nephropathy (HBV-MN) is the most common renal manifestation in patients with HBV infection,1, 2, 3 possibly linked to subepithelial deposits of viral immune complexes.4, 5 HBV RNA and DNA were detected in glomerular and tubular cells, although a pathogenetic role for these viral nucleic acids remains to be confirmed.6 The effects of vaccination programs on the decline of HBV-associated MN, particularly in Asian and African children,7, 8 further support a possible relationship between HBV infection and MN.9

Identification in 2009 of PLA2R as the major antigen associated with idiopathic membranous nephropathy provided the first diagnostic biomarker.10 The 2 available assays (immunofluorescence test assay [IFTA] and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) for the detection of circulating anti-PLA2R antibodies (PLA2R-Abs) have shown that PLA2R-Abs are a specific and sensitive biomarker of MN, being detected in 70% to 80% of patients with primary MN worldwide in early serum samples, and consistently absent in healthy individuals and in patients with other nephropathies or autoimmune diseases.11 Because anti-PLAR antibody levels fluctuate and can rapidly decrease under immunosuppressive treatment, detection of PLA2R antigen in subepithelial immune deposits of patients with MN is even more sensitive than serology.12, 13 Although Hoxha et al. suggested that the diagnosis between primary MN and secondary MN could rely on the presence or absence of PLA2R antigen in the immune deposits,14 other investigators showed that the antigen could be detected in cases of active sarcoidosis,15, 16 hepatitis C virus,17 and HBV infection–associated MN.13, 18 In the Chinese population, 25 of 39 patients (64%) with HBV-MN had deposited subepithelial PLA2R antigen, and all tested sera contained anti-PLA2R antibody.18 These findings suggest that HBV infection could be the trigger of autoimmunity anti-PLA2R.

Whatever the mechanism of autoimmunity, we are facing the conundrum of antiviral versus immunosuppressive therapy with the risk of aggravating the viral infection. Most data have been obtained in small-scale case series published before the availability of anti-PLA2R antibody assays, and a standard of care has not yet been established.19, 20 Here, we report the first 2 cases in which rituximab was used after controlling viral replication.

Case Presentation

Case 1

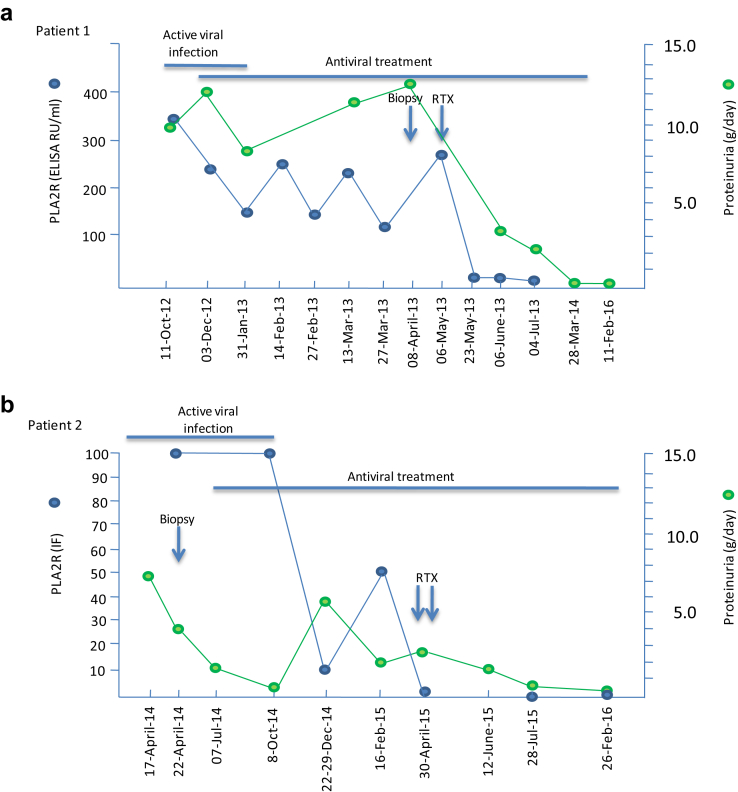

A 44-year-old man of Moroccan origin presented at Dijon University Hospital in October 2012 with lower-extremity edema and lower chest pain. His medical history was unremarkable. His lungs were clear with decreased ventilation at the bases. Blood pressure was 155/117 mm Hg. Urinary dipstick showed 3+ proteinuria. Laboratory studies revealed a serum creatinine of 1.0 mg/dl (92 μmol/l), urine protein-to-creatinine ratio of 11 g/g, serum albumin of 1.3 g/dl (13 g/l), and normal liver test results. Ultrasound examination revealed thrombosis of the left renal vein, and angiography showed bilateral lung emboli. Active HBV infection was diagnosed: viral load was 2.7 log with positivity for HBs antigen, anti-HBc, and anti-HBe antibody; HBe antigen and anti-HBs antibody were negative (Table 1). PLA2R-Abs were measured at 333 RU/ml by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. PLA2R-Ab IgG4 was the prevailing subclass (IgG4 > IgG3 > IgG1 > IgG2) of anti−PLA2R-Abs measured by IFTA (see Supplementary Material). Tests for antinuclear antibody (ANA), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), and rheumatoid factor were negative. Serum complement levels (C3, C4, and CH50) were normal. The patient was treated for 4 months with antivitamin K, entecavir, and a combination of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, calcium channel blocker, α-adrenergic blocker, and diuretic. During this time period, he maintained heavy proteinuria and high levels of PLA2R-Abs (Figure 1a), although viral replication became undetectable in January 2013 about 2 months after entecavir.

Table 1.

Distinct teaching points

| Hepatitis B should be added to the list of potential diseases associated with PLA2R-related membranous nephropathy. |

| It is likely that active viral infection triggers auto-immunity against PLA2R. |

| Antiviral treatment should be the first-line therapy. |

| Rituximab can be used safely and efficiently in patients with controlled viral infection who have not reached immunological remission (defined by disappearance of anti-PLA2R antibodies). |

| Antiviral therapy should be associated with rituximab and continued for several months after completion of immunosuppressive therapy because of risk of reactivation of the viral infection. |

| Further studies are needed to understand how hepatitis B virus triggers the production of anti-PLA2R antibodies. |

Figure 1.

Summary of clinical outcomes and treatment in case 1 (a) and case 2 (b). ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IF, immunofluorescence; RTX, rituximab.

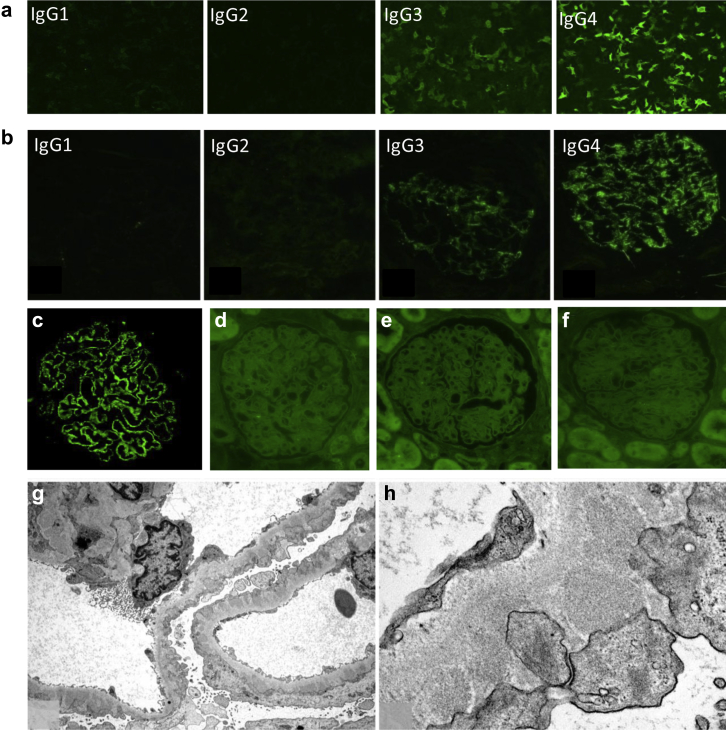

The patient was then referred in April 2013 to our Nephrology Department at the Tenon Hospital for a transjugular kidney biopsy before starting rituximab. The clinical situation was unchanged. Laboratory investigations revealed a serum creatinine of 0.84 mg/dl (74 μmol/l), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) by Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation of 105 ml/min per 1.73 m2, urine protein-to-creatinine ratio of 13 g/g, serum albumin of 2.4 g/dl (24 g/l), and normal urinary sediment. HBV load was undetectable. The kidney biopsy specimen showed a type-1 MN with mildly thickened basement membranes, thin mesangial stalks, and normal interstitium with < 5% fibrosis (see Supplementary Material). There was no endocapillary proliferation or crescent. Immunofluorescence examination showed diffuse granular membranous deposits of IgG, C3, and both light-chain isotypes. Staining for C1q and fibrinogen was negative; rare subepithelial deposits of IgA without IgM were seen. Subclass analysis showed mostly IgG4 deposits with low amounts of IgG3, in perfect agreement with the results of the IFTA assay of circulating PLA2R-Abs (Figure 2a and b). PLA2R staining of the biopsy specimen was also strongly positive (Figure 2c). Detection of HbS, HbC, and Hbe antigens were negative (Figure 2d, e, and f). By electron microscopy, subepithelial electron-dense deposits were observed, without any organization or viral particle aspect (Figure 2g and h).

Figure 2.

Detection of anti-PLA2R antibodies in serum and characterization of immune deposits in kidney biopsy sample (patient 1). (a) Detection and isotyping of circulating anti-PLA2R antibodies in patient’s serum using immunofluorescence test (Euroimmun). (b) Immunostaining for IgG subclasses (cryosection). (c) Immunofluorescence analysis of paraffin kidney biopsy sample shows PLA2R in immune deposits but not viral antigens (d) Hbs, (e) Hbe, or (f) Hbc. (g,h) Representative segment of the capillary wall analyzed by electron microscopy. Electron-dense deposits seen on the outer aspect of the glomerular basement membrane do not contain viral particles or other organized structures.

Six months after initiation of antiviral therapy and 4 months after negative viral load, the patient received 2 infusions of rituximab (375 mg/m2) at a 1-week interval while antiviral treatment was continued at the same dose. Immunological remission (undetectable anti-PLA2R antibody) was achieved 17 days after the first rituximab infusion, together with a marked decrease of 24-hour proteinuria (3.28 g/g) (Figure 1a). Antiviral treatment was stopped in August 2014. On last follow-up, in February 2016, daily proteinuria was 0.15 g, serum albumin was 3.7 g/dl (37g/l), and serum creatinine was 0.81 mg/dl (71 μmol/l); there was no viral replication. Viral reactivation (2.96 log; 5346 copies) was noted in May 2017.

Case 2

The second patient was a 26-year-old man from the Republic of Benin who presented in April 2014 with bilateral lower-extremity edema since 1 month. He had a previous medical history of malaria and HBV infection since 2009 without any treatment. Laboratory studies revealed serum creatinine of 1.11 mg/dl (98 μmol/l), serum albumin of 1.77 g/dl (17.7g/l), urine protein-to-creatinine ratio of 7.4 g/d, and PLA2R-Ab at 1/50 by IFTA. The kidney biopsy showed a type-2 MN, with thickened basement membranes and diffuse subepithelial deposits and spikes, but a normal interstitium with < 5% fibrosis. Immunofluorescence examination revealed diffuse, granular membranous deposits of IgG, C3, and both light-chain isotypes. Staining for C1q and fibrinogen was negative; no subepithelial deposits of IgA and IgM were seen. Subclass analysis showed mostly IgG4 deposits with low amounts of IgG2. PLA2R staining was strongly positive. Detection of HbS, HbC, and HBe antigens was negative (Table 1). Active HBV infection was confirmed (733 copies/ml). Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and entecavir were started at the end of April 2014 (Figure 1b). HBV-DNA became undetectable since November 2014. Because of fluctuating levels of anti-PLA2R antibodies in the first trimester of 2015, the patient received 2 infusions of rituximab (375 mg/m2) at a 1-week interval, and subsequently achieved immunological and renal remission without viral reactivation. The patient was still on antiviral treatment at last follow-up.

Discussion

The association of a viral infection and an auto-immune disease is a therapeutic conundrum because of the risk of aggravation of the viral infection with immunosuppressive agents. In children, HBV-associated MN has a favorable prognosis with high spontaneous remission rate with antiviral drugs; however, in adults, resolution of proteinuria is uncommon, and patients who do not clear the virus usually develop progressive renal failure.20 Because of the poor tolerance of interferon and of the toxicity of adefovir, entecavir and tenofovir (the latter particularly in co-infected HIV patients) are the most commonly used. This report first shows the efficacy and safety of rituximab. In case 1, in which MN remained immunologically and clinically active after 6 months of antiviral treatment despite full control of viral replication, rituximab appeared to have a dramatic effect. Because the patient was cured by anti−B-cell therapy, not by efficient antiviral therapy, one can hypothesize that PLA2R immunization played a critical role in the pathogenesis of the disease. This hypothesis is supported by the parallel, spectacular decrease of proteinuria and anti-PLA2R antibody after rituximab infusion. However, these data do not exclude a role for HBV infection in the triggering of PLA2R autoimmunization. In case 2, in which rituximab was infused in a period of fluctuation of PLA2R-Ab titer, we suggest that rituximab helped consolidation of immunological remission followed by clinical remission.

The relationship between HBV infection and MN remains unclear. We detected subepithelial PLA2R deposits without HBV antigens in our 2 patients. The absence of deposited HBV antigens contrasting with previous literature,5, 21, 22although we used the same source of anti-HBV antibodies, might be explained by the use of a very stringent technique to avoid interaction of the test antibody specific for HBV antigens with deposited IgG. Our observations in Africans confirm those made in a Chinese population, in which 64% of patients with HBV-MN also had PLA2R antigen in immune deposits.18 The mechanisms whereby HBV may trigger autoimmunity may involve molecular mimicry, alterations of regulatory T-cells (Treg), or B-cell activation.23, 24 HBV scanning of protein databases has revealed regional similarities between HBV proteins and antigenic targets of nuclear and smooth muscle antibodies.25 Alignment of the immunodominant peptide of PLA2R against a database of microbial proteins identified a small sequence shared by a cell wall enzyme, D-alanyl-D alanine carboxypeptidase, common in several bacterial strains, including Clostridia species, but no mimicry of HBV viral antigens.26 No direct link between Treg number and/or function and HBV-related immunopathological manifestations has been reported.23 Little is known about the effect of chronic HBV infection on B-lymphocytes, although there is evidence that HBV is present in these cells.27

Very importantly, rituximab associated with entecavir did not induce a viral reactivation or alterations of liver test results. Rituximab is safe, provided that viral replication is under control and that antiviral therapy is continued to avoid a burst of viral replication.28 Long-term surveillance of the viral status is warranted, because reactivation can occur well after completion of immunosuppressive therapy. The current recommendation of stopping antiviral prophylaxis 6 to 12 months after the cessation of chemotherapy may not fully protect all patients from HBV reactivation, as indicated by our case 1. The optimal duration of follow-up needs to be determined, and until better guidelines are set, there is no choice but to keep monitoring patients for reactivation for as long as possible.29 Furthermore, we do not yet know whether the antiviral/rituximab strategy used (successfully) in these 2 cases would also be safe in individuals highly expressing cccDNA in the liver or pgRNA in the blood.30

In conclusion, these case reports suggest a link between HBV infection and MN through induction of PLA2R autoimmunization. Antiviral therapy should first be used to control viral infection. This treatment can subsequently be associated with rituximab in cases in which immunological activity monitored with anti-PLA2R antibody persists after control of viral replication. Antiviral therapy should be continued for a long time after completion of immunosuppressive treatment.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by grants from the European Research Council ERC-2012-ADG_20120314 (Grant Agreement 322947) and from the 7th Framework Programme of the European Community Contract 2012-305608 (European Consortium for High-Throughput Research in Rare Kidney Diseases). LB was supported by a grant from the Swiss National Foundation (P2GEP3_162179).

Footnotes

Supplementary Materials and Methods. Circulating antibodies against PLA2R were measured by IFTA and ELISA (Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany). IgG subclass of PLA2R-specific antibodies were assessed by IFTA using IgG subclass of PLA2R-specific antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich). Kidney biopsy specimens were analyzed for IgG subclass and the presence of PLA2R antigen (Atlas Antibodies) in immune deposits. See Supplementary Materials and Methods for further details.

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at www.kireports.org.

Supplementary Material

Circulating antibodies against PLA2R were measured by IFTA and ELISA (Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany). IgG subclass of PLA2R-specific antibodies were assessed by IFTA using IgG subclass of PLA2R-specific antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich). Kidney biopsy specimens were analyzed for IgG subclass and the presence of PLA2R antigen (Atlas Antibodies) in immune deposits. See Supplementary Materials and Methods for further details.

References

- 1.Combes B., Shorey J., Barrera A. Glomerulonephritis with deposition of Australia antigen-antibody complexes in glomerular basement membrane. Lancet. 1971;2:234–237. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)92572-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu G., Huang T. Hepatitis B virus-associated glomerular nephritis in East Asia: progress and challenges. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22:161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhimma R., Coovadia H.M. Hepatitis B virus-associated nephropathy. Am J Nephrol. 2004;24:198–211. doi: 10.1159/000077065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson R.J., Couser W.G. Hepatitis B infection and renal disease: clinical, immunopathogenetic and therapeutic considerations. Kidney Int. 1990;37:663–676. doi: 10.1038/ki.1990.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai K.N., Li P.K., Lui S.F. Membranous nephropathy related to hepatitis B virus in adults. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1457–1463. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199105233242103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lai K.N., Ho R.T., Tam J.S., Lai F.M. Detection of hepatitis B virus DNA and RNA in kidneys of HBV related glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 1996;50:1965–1977. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liao M.T., Chang M.H., Lin F.G. Universal hepatitis B vaccination reduces childhood hepatitis B virus-associated membranous nephropathy. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e600–e604. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burnett R.J., Kramvis A., Dochez C., Meheus A. An update after 16 years of hepatitis B vaccination in South Africa. Vaccine. 2012;7;30(suppl 3):C45–C51. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Y., Ma Y.P., Chen D.P. A meta-analysis of antiviral therapy for hepatitis B virus-associated membranous nephropathy. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0160437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beck L.H., Jr., Bonegio R.G., Lambeau G. M-type phospholipase A2 receptor as target antigen in idiopathic MN. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:11–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ronco P., Debiec H. Pathophysiological advances in membranous nephropathy: time for a shift in patient’s care. Lancet. 2015;385:1983–1992. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60731-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stehle T., Audard V., Ronco P., Debiec H. Phospholipase A2 receptor and sarcoidosis-associated membranous nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30:1047–1050. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Debiec H., Ronco P. PLA2R autoantibodies and PLA2R glomerular deposits in membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:689–690. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1011678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoxha E., Kneissler U., Stege G. Enhanced expression of the M-type phospholipase A2 receptor in glomeruli correlates with serum receptor antibodies in primary membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2012;82:797–804. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Svobodova B., Honsova E., Ronco P. Kidney biopsy is a sensitive tool for retrospective diagnosis of PLA2R-related membranous nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:1839–1844. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knehtl M., Debiec H., Kamgang P. A case of phospholipase A(2) receptor-positive membranous nephropathy preceding sarcoid-associated granulomatous tubulointerstitial nephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57:140–143. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larsen C.P., Messias N.C., Silva F.G. Determination of primary versus secondary membranous glomerulopathy utilizing phospholipase A2 receptor staining in renal biopsies. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:709–715. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie Q., Li Y., Xue J. Renal phospholipase A2 receptor in hepatitis B virus-associated membranous nephropathy. Am J Nephrol. 2015;41:345–353. doi: 10.1159/000431331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng X.Y., Wei R.B., Tang L. Meta-analysis of combined therapy for adult hepatitis B virus-associated glomerulonephritis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:821–832. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i8.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elewa U., Sandri A.M., Kim W.R., Fervenza F.C. Treatment of hepatitis B virus-associated nephropathy. Nephron Clin Pract. 2011;119:c41–c49. doi: 10.1159/000324652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kong D., Wu D., Wang T. Detection of viral antigens in renal tissue of glomerulonephritis patients without serological evidence of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e535–e538. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai A.S., Lai K.N. Viral nephropathy. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2006;2:254–262. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vergani D., Mieli-Vergani G. Autoimmune manifestations in viral hepatitis. Semin Immunopathol. 2013;35:73–85. doi: 10.1007/s00281-012-0328-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cacoub P., Terrier B. Hepatitis B-related autoimmune manifestations. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35:125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gregorio G.V., Choudhuri K., Ma Y. Mimicry between the hepatitis B virus DNA polymerase and the antigenic targets of nuclear and smooth muscle antibodies in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Immunol. 1999;162:1802–1810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fresquet M., Jowitt T.A., Gummadova J. Identification of a major epitope recognized by PLA2R autoantibodies in primary membranous nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:302–313. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014050502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pontisso P., Poon M.C., Tiollais P., Brechot C. Detection of hepatitis B virus DNA in mononuclear blood cells. Br Med J. [Clin Res Ed] 1984;288:1563–1566. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6430.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Bisceglie A.M., Lok A.S., Martin P. Recent US Food and Drug Administration warnings on hepatitis B reactivation with immune-suppressing and anticancer drugs: just the tip of the iceberg? Hepatology. 2015;61:703–711. doi: 10.1002/hep.27609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakaya A., Fujita S., Satake A. Delayed HBV reactivation in rituximab-containing chemotherapy: how long should we continue anti-virus prophylaxis or monitoring HBV-DNA? Leuk Res. 2016;50:46–49. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2016.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allweiss L., Dandri M. The role of cccDNA in HBV maintenance. Viruses. 2017;9:156. doi: 10.3390/v9060156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Circulating antibodies against PLA2R were measured by IFTA and ELISA (Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany). IgG subclass of PLA2R-specific antibodies were assessed by IFTA using IgG subclass of PLA2R-specific antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich). Kidney biopsy specimens were analyzed for IgG subclass and the presence of PLA2R antigen (Atlas Antibodies) in immune deposits. See Supplementary Materials and Methods for further details.