Abstract

Objective

This observational study was a retrospective analysis of prospectively-collected Hopkins Lupus Cohort data, to compare long-term renal survival in patients with lupus nephritis (LN) who achieved complete (CR), partial (PR) or no remission following standard of care LN induction therapy.

Methods

Eligible patients with biopsy-proven LN (revised American College of Rheumatology or Systemic Lupus Collaborating Clinics criteria) were identified and categorised into ordinal (CR, PR or no remission) or binary (response or no response) renal remission categories at 24 months post diagnosis (modified Aspreva Lupus Management Study [mALMS] and modified Belimumab International Lupus Nephritis Study [mBLISS-LN] criteria). The primary endpoint was long-term renal survival (without end-stage renal disease [ESRD] or death).

Results

In total 176 patients met the inclusion criteria. At Month 24 post biopsy, more patients met mALMS remission criteria (CR=59.1%, PR=30.1%) than mBLISS-LN criteria (CR=40.9%, PR=16.5%). During subsequent follow-up, 18 patients developed ESRD or died. Kaplan–Meier plots suggested patients with no remission at Month 24 were more likely than those with PR or CR to develop the outcome using either mALMS (p=0.0038) and mBLISS-LN (p=0.0097) criteria for remission. Based on Cox regression models adjusted for key confounders, those in CR according to the mBLISS-LN (HR 0.254; 95% CI 0.082, 0.787; p=0.0176) and mALMS criteria (HR 0.228; 95% CI 0.063, 0.828; p=0.0246) were significantly less likely to experience ESRD/mortality than those not in remission.

Conclusion

Renal remission status at 24 months following LN diagnosis is a significant predictor of long-term renal survival, and a clinically relevant endpoint.

Keywords: End-Stage Renal Disease, Cohort Studies, LN, Mortality, Remission Induction, Survival

Introduction

Although there have been improvements in both diagnosis and treatment of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) over recent decades, lupus nephritis (LN) remains an indicator of poor prognosis (1–3). Active LN progresses to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in approximately 10–30% of patients (4). Patients with LN who develop ESRD have a much higher mortality rate than those who do not develop ESRD (5, 6), with renal injury considered the most important predictor of mortality in patients with SLE (4).

Clinical trials in LN have been designed to demonstrate induction of renal remission (as a measure of response to therapy) based on various laboratory measures of renal function and activity. These measures have been used to create clinical endpoints based on the degree of renal response to treatment at a specific time point, including an ordinal endpoint (no remission, partial remission [PR] and complete remission [CR]) (7, 8) or binary endpoint (response or no response) (8, 9). The definitions of both CR and PR and the designated periods that these endpoints have been assessed have varied in previous studies (10–12); however, few studies have assessed the long-term clinical relevance of PR (13).

The present study aimed to retrospectively compare long-term renal survival in patients with CR, PR or no remission, as defined by criteria from the Aspreva Lupus Management Study (ALMS) (9) and the Belimumab International Lupus Nephritis Study (BLISS-LN), using both binary and ordinal renal remission criteria in a large clinical cohort. In this study both these criteria were modified to exclude urinary sediments (referred to throughout as mALMS and mBLISS-LN).

The primary objectives of this study were to: describe renal remission following conventional therapies in LN at 24 months of treatment; assess the proportion of patients achieving PR at 24 months and who subsequently achieved CR at 36 months (CR, PR or no remission as defined by mALMS and mBLISS-LN criteria); describe long-term survival by remission status at 24 months (binary and ordinal renal remission criteria); and assess the association between renal remission at 24 months (binary and ordinal renal remission criteria) and longterm survival (no ESRD and/or mortality) after adjusting for potential confounders.

Methods

Study design

This was an observational study (GSK Study WEUKBRE6068) involving retrospective analysis of the prospectively collected Hopkins Lupus Cohort study data. The study assessed long-term outcomes of LN based on the degree of renal remission following standard of care therapy as measured at 24 months post treatment.

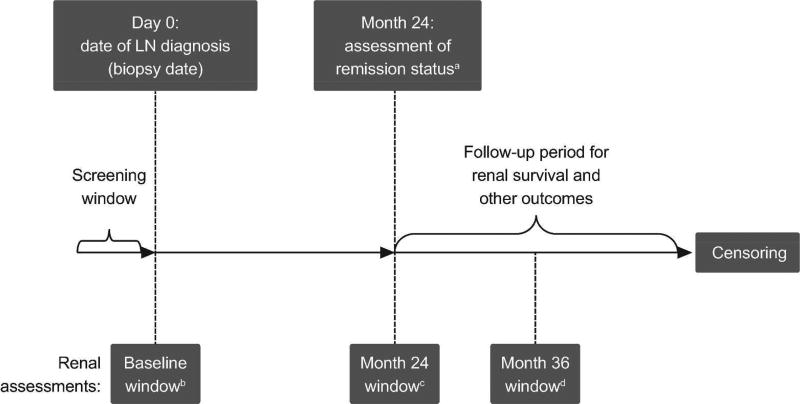

Eligible patients with LN were identified from the Hopkins Lupus Cohort records, and patients’ remission status was categorised retrospectively into ordinal (CR, PR or no remission) or binary (response or no response) renal remission categories at 24 months post LN diagnosis (date of positive biopsy), based on available laboratory measures recorded during standard clinical care. Patients were followed-up for long-term renal survival from Month 24 post LN diagnosis until end of follow-up (due to outcome event, loss to follow-up, or end of study dataset [December 2013]) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study design.

aDegree of remission status achieved at Month 24 post LN biopsy data, was used as the key exposure variable in this study. Renal remission status was also defined retrospectively at other study time points (Month 6 and Month 36)

bClosest date to Day 0 (LN biopsy date) within period 3 months prior to Day 0 to 3 months post Day 0

cClosest date to Day 730 (Month 24) within a period of 3 months prior to Month 24 to 3 months post Month 24

dClosest date to Day 1095 (Month 36) within a period of 3 months prior to 3 months post Month 36 LN, lupus nephritis

As data were collected in a real-world observational setting, renal functional assessments were not conducted at strict time points at regular intervals. Therefore, a designated window of ±3 months was defined around the Day 0 window, for measurement of baseline renal function and model covariates, and the Month 24 post biopsy date. The result most proximal to the Month 24 time point was selected. It was also anticipated that few patients would have renal function screening at exactly 6 months and 36 months post biopsy. Therefore, for the Month 36 assessments, a window of ±3 months was applied, to allow calculation of remission status. A hierarchy was set for defining which laboratory test to use for each remission measure if more than one type of measure was available (Supplementary Table 1). If more than one test was available during an assessment window, an algorithm based on clinical preferences was developed to select the most appropriate test.

The Hopkins Lupus Cohort study is approved on an annual basis by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (Research Project Notification: NA_00039294) and informed written consent is obtained from all participants.

Patients

Eligible patients were ≥18 years of age at diagnosis, had SLE according to the revised American College of Rheumatology or the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) criteria (14, 15) plus biopsy record of International Society of Nephrology (ISN) class III, IV, V or mixed LN. Patients had to have made at least one visit to the Johns Hopkins Lupus Center in the 3-month period following biopsy and at least one clinic visit during the follow-up period (initiation of induction therapy plus 24 months) to allow assessment of long-term renal outcomes. Each patient was required to have sufficient laboratory data for assessment of renal remission at 24 months. Patients with ESRD at the initiation of induction therapy were excluded.

Remission

Ordinal and binary remission categories were defined according to criteria in the ALMS (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00377637) (9) and BLISS-LN trials (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT01639339; GSK study 114054) (Supplementary Table 1). These criteria were modified (mALMS and mBLISS-LN) to exclude urinary sediment data following findings indicating that these data had low sensitivity and poor predictive value in predicting LN outcomes (16, 17). For the current study, mALMS and mBLISS-LN criteria were applied at 24 months.

For the ordinal remission criteria, in accordance with mALMS criteria, CR was defined as occurrence of a return to normal serum creatinine and urine protein ≤0.5 g/day. PR was defined as one of either a return to normal serum creatinine or urine protein ≤0.5 g/day. As per mBLISS-LN criteria, CR (ordinal criteria) was defined as occurrence of estimated creatinine clearance within the normal range, and urinary protein:creatinine ratio <0.5. Creatinine clearance was estimated according to the Cockcroft-Gault formula (18). PR was defined as occurrence of creatinine clearance of no more than 10% below the baseline value or within normal range and ≥50% decrease in urinary protein:creatinine ratio to <1.0 (if the baseline ratio was ≤3.0) or <3.0 (if the baseline ratio was >0.3).

For the binary remission criteria (remission or no remission), in accordance with mALMS criteria, remission was defined as decrease in urine protein:creatinine ratio to <3 in patients with baseline nephritic range proteinuria (≥3 urine protein:creatinine ratio), and decrease in the urine protein:creatinine ratio by ≥50% in patients with sub-nephrotic proteinuria (<3 urine protein:creatinine ratio). In accordance with mBLISS-LN criteria remission was defined as meeting either the CR or the PR ordinal criteria (no remission defined as not meeting the response criteria).

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was long-term renal survival defined as survival without ESRD or mortality. ESRD was recorded prospectively in the Hopkins Lupus cohort at each clinic visit if patients had received renal replacement therapy (dialysis or transplantation), as part of the SLICC/ACR Damage Index (19). The primary predictor of interest was renal remission status (ordinal criteria: CR, PR or no remission) according to mBLISS-LN and mALMS criteria at 24 months post biopsy date (Figure 1). Secondary endpoints included the incidence of chronic renal insufficiency and serum creatinine over time. Chronic renal insufficiency was defined as new kidney damage or new occurrence of creatinine clearance <60 mL/min/on at least two consecutive measurement occasions ≥3 months apart. In post hoc analyses, proteinuria status (yes/no) at Month 24 was explored, to investigate any association with renal survival.

Analysis

The primary study analysis was a comparison of the rates of renal survival between patients achieving PR or CR of LN at Month 24 and those who achieved no remission. Survival analysis (Kaplan–Meier plots with log-rank test and Cox Proportional Hazards regression) was used to compare event rates by remission status and assess the association between remission status at 24 months and renal death (ESRD or mortality), adjusting for potential confounding variables. As this was an observational retrospective analysis, safety data such as adverse event reporting was not collected.

Multivariate analyses

Potential confounding variables considered included ISN class (III, IV or V lupus glomerulonephritis at date of biopsy), early remission, age at date of biopsy, gender, race/ethnicity (black vs other) and SLICC Damage Index score (Day 0 window). A model-building approach was taken to produce final models according to the following rules: each variable was added in turn; those for which the remission category hazard ratio (HR) changed by >10% were considered a confounder and entered into the model. Due to concerns about the low number of events observed and the high number of covariates, restricted models were constructed based on assessment of confounding. The number of covariates permitted in the model was set at a maximum of two. Where there were >2 confounders identified, the two confounders with the greatest % change in HR were entered.

Results

Patients

Based on the retrospective review of histology records during the screening window, 520 patients in the Hopkins Lupus Cohort had a biopsy record indicating ISN category III, IV or V LN. Of these, 176 patients with LN were eligible for inclusion in this present analysis (Table 1). The majority of these patients were female (91.5%; n=161), just over half of the patients were black (53.4%; n=94) and the distribution across the included ISN categories was similar: III (25.0%; n=44), IV (29.0%; n=51), V (22.7%; n=40) and mixed (23.3%; n=41) (Table 2). Three quarters of patients had received induction therapy in the period 6 months before or after biopsy date (Table 2).

Table 1.

Attrition flow

| Characteristic | Attrition flow n (%) (N=2,313) |

|---|---|

| Patients with SLE | 2,313 (100.0) |

| LN ISN category III/IV/V | 520 (22.5) |

| At least one visit within 3 month of biopsy date | 282 (12.2) |

| Age ≥18 years at biopsy date (Day 0) | 277 (12.0) |

| Sufficient data within Day 0 window | 275 (11.9) |

| Sufficient data within Month 24 window | 189 (8.2) |

| At least one visit made in follow-up period (after Month 24) | 181 (7.8) |

| No ESRD during Day 0 window | 176 (7.6) |

|

| |

| Patients selected for this analysis | 176 |

ESRD, end-stage renal disease; ISN, International Society of Nephrology; LN, lupus nephritis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus

Table 2.

Baseline demographics and patient characteristics

| Characteristic | LN patient population (N=176) | |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous variables | Mean (SD) | Median (min, max) |

|

| ||

| Age at biopsy date (Day 0; years) | 36.1 (11.81) | 35.0 (18.00, 76.00) |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.0 (0.63) | 0.8 (0.40, 4.70) |

| Urinary creatinine (mg/dL) | 135.7 (110.15) | 109.0 (27.00, 655.00) |

| Urinary protein:creatinine ratio | 1.5 (1.80) | 0.8 (0, 9.91) |

| Urinary RBC (RBC/hpf) | 8.6 (20.07) | 2.5 (0, 100.00) |

| SLICC Damage Index score | 2.2 (2.61) | 1.0 (0, 12.00) |

|

| ||

| Categorical variables | n (%) | |

|

| ||

| LN ISN category | III | 44 (25.0) |

| IV | 51 (29.0) | |

| V | 40 (22.7) | |

| Mixed | 41 (23.3) | |

|

| ||

| Initiated induction therapy in 6 months before or after biopsy date | CYC | 28 (15.9) |

| MMF | 88 (50.0) | |

| AZA | 17 (9.7) | |

| RTX | 0 | |

| None | 43 (24.4) | |

| CYC or MMF or AZA or RTX | 133 (75.6) | |

|

| ||

| Decade of biopsy | 1989 or earlier | 2 (1.1) |

| 1990–1999 | 36 (20.5) | |

| 2000–2009 | 123 (69.9) | |

| 2010–2013 | 15 (8.5) | |

|

| ||

| Gender | Female | 161 (91.5) |

|

| ||

| Race/ethnicity | Black | 94 (53.4) |

| Other | 82 (46.6) | |

|

| ||

| Urine protein dipstick* (semi-quantitative) category | 0 | 18 (10.2) |

| 0.5 | 12 (6.8) | |

| 1 | 23 (13.1) | |

| 2 | 48 (27.3) | |

| 3 | 63 (35.8) | |

| 4 | 11 (6.3) | |

| 5 | 0 | |

|

| ||

| Hypertension** | 138 (78.4) | |

|

| ||

| Diabetes*** | 29 (16.5) | |

|

| ||

| History of MI | 4 (2.3) | |

|

| ||

| Any hydroxychloroquine use from Day 0 to Month 24 | 123 (69.9) | |

| Any prednisone use from Day 0 to Month 24 | 164 (93.2) | |

AZA, azathioprine; CYC, cyclophosphamide; ISN, International Society of Nephrology; LN, lupus nephritis; MI, myocardial infarction; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; RBC/hpf, red blood cells per high power field; RTX, rituximab; SD, standard deviation; SDI, SLICC damage index; SLICC, Systemic Lupus Collaborating Clinics

Dipstick results were selected for the purposes of describing the cohort at baseline, as this particular method of measuring proteinuria was complete for all patients during the baseline window

Defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg on two or more occasions OR hypertension recorded as part of the SDI at any clinic visit

Renal biopsy established that proteinuria was lupus-related and not diabetes-related

Remission

At 24 months post biopsy, more patients met the ordinal mALMS renal remission criteria than the mBLISS-LN criteria (Table 3). However, the distribution of patients meeting the binary renal remission criteria was similar between the mALMS and mBLISS-LN criteria (Table 3).

Table 3.

Renal remission following conventional therapy in LN at 24 months of treatment

| Renal remission criteria | Type of response | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ordinal mALMS | CR | 104 (59.1) |

| PR | 53 (30.1) | |

| No | 19 (10.8) | |

|

| ||

| Ordinal mBLISS-LN | CR | 72 (40.9) |

| PR | 29 (16.5) | |

| No | 75 (42.6) | |

|

| ||

| Binary mALMS† | Response | 109 (61.9) |

| No response | 64 (36.4) | |

|

| ||

| Binary mBLISS-LN | Response | 101 (57.4) |

| No response | 75 (42.6) | |

3 patients lacked sufficient data to be classified by binary mALMS criteria

CR, complete remission; mALMS, modified Aspreva Lupus Management Study; mBLISS-LN, modified Belimumab International Lupus Nephritis Study; PR, partial remission

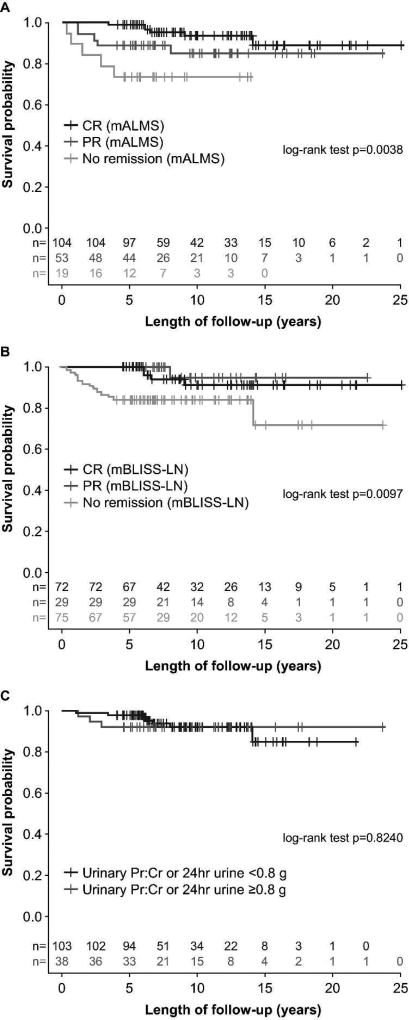

During the subsequent follow-up period, 18 patients developed ESRD or died. Patients with no remission at Month 24 post biopsy (ordinal criteria) were more likely than those with PR or CR to develop ESRD according to both the mALMS (p=0.0038) (Figure 2A) and mBLISS-LN (p=0.0097) criteria (Figure 2B). Kaplan–Meier analyses suggested that proteinuria alone was not predictive of ESRD or mortality (p=0.8240) (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Long-term renal survival based on remission category at 24 months post biopsy: A. mALMS criteria (ordinal) B. mBLISS-LN criteria (ordinal) C. proteinuria (binary criteria).

CR, complete remission; mALMS, modified Aspreva Lupus Management Study; mBLISS-LN, modified Belimumab International Lupus Nephritis Study; PR, partial remission; Pr:Cr, protein:creatinine Cut-off of 0.8g/day selected due to a recent publication (16)

Effects of covariates are also shown in Supplementary Table 2. Based on Cox regression models adjusted for key confounders, those in CR (ordinal criteria) according to both the mBLISS-LN and mALMS criteria were significantly less likely to experience ESRD/mortality than those not in remission (Supplementary Table 2). Those in PR were also less likely to experience ESRD/mortality, and while this did not reach statistical significance, the HR among those in PR defined by mBLISS was lower than that of the HR for those in CR (Supplementary Table 2).

Of 53 patients who achieved mALMS criteria PR at Month 24, 14 (26.4%) achieved CR at Month 36; of 29 patients who achieved mBLISS-LN criteria PR at Month 24, 6 (20.7%) achieved CR at Month 36.

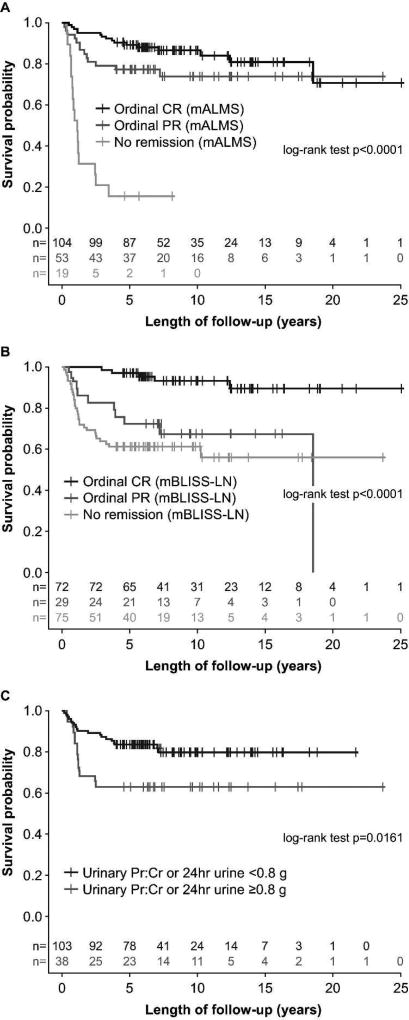

Chronic renal insufficiency

During the follow-up period, 45/176 patients developed chronic renal insufficiency. Based on Cox regression models, those in CR and PR were significantly less likely to experience chronic renal insufficiency based on the mALMS criteria (CR: HR 0.077, p<0.0001; PR: HR 0.152, p<0.0001) (Figure 3A). Similarly, those in CR according to the mBLISS-LN criteria (but not PR) were significantly less likely to develop chronic renal insufficiency (CR: HR 0.122, p<0.0001; PR: HR 0.611, p=0.1824) (Figure 3B). Proteinuria at 24 months was significantly associated with chronic renal insufficiency (p=0.0161) (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Long-term chronic renal insufficiency-free survival based on status at 24 months: A. mALMS criteria (ordinal) B. mBLISS-LN criteria (ordinal) C. proteinuria (binary criteria).

CR, complete remission; mALMS, modified Aspreva Lupus Management Study; mBLISS-LN, modified Belimumab International Lupus Nephritis Study; PR, partial remission; Pr:Cr, protein:creatinine Cut-off of 0.8g/day selected due to a recent publication (16)

Serum creatinine

The mean (standard deviation) serum creatinine levels remained within the normal range and stable between Years 1 to 3 after start of follow-up for those in CR or PR at Month 24, according to both the ordinal mALMS and mBLISS-LN criteria. For those not in remission, serum creatinine levels remained elevated although appeared to decrease from Years 1 to 3, according to both sets of criteria (Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

This observational study is the first of its kind to assess the long-term outcomes of LN based on degree of renal remission achieved, in a real-world setting. Regardless of definition, renal remission status at Month 24 in patients with LN was a statistically significant predictor of long-term renal survival. Patients with CR 24 months post biopsy (by both mBLISS-LN and mALMS criteria) were significantly less likely to experience ESRD/mortality than patients not in remission. Furthermore, patients with PR at 24 months post biopsy (by both mBLISS-LN and mALMS criteria) were less likely to experience ESRD/mortality than patients not in remission. Although the PR/ESRD/mortality association was not statistically significant, the result approached significance for the mBLISS-LN criteria (p=0.0599). These results support previous findings in a small number of patients where PR in LN was associated with significantly improved patient and renal survival, compared with patients who had no remission (13). In that previous study, renal survival at 10 years was 94% (CR) and 45% (PR) versus 19% (no remission), and the patient survival without ESRD at 10 years was 92% (CR) and 43% (PR) versus 13% (no remission) (13). The composite mBLISS-LN and mALMS remission scores, which included consideration of creatinine levels in addition to urinary proteinuria, did seem to perform better in predicting renal survival compared with assessment of proteinuria alone.

The association between renal remission and chronic renal insufficiency was also assessed in this study. Patients with no remission (mALMS) appeared to have a particularly marked reduction in long-term chronic renal insufficiency-free survival, compared with those in the mALMS PR or CR groups, although this was not tested statistically. A less marked separation was observed for the mBLISS-LN criteria. As both remission and chronic renal insufficiency are defined based on serum creatinine this association is not unexpected. The threshold for meeting the mALMS PR or CR criteria appeared to be lower than for meeting the mBLISS-LN criteria, perhaps explaining the poor outcomes of those remaining in the ALMS ‘no remission’ category compared with those in the mBLISS-LN ‘no remission’ category. A relatively small percentage of patients with a PR at Month 24 (mALMS criteria, 26.4%; mBLISS-LN criteria, 20.7%) achieved CR at Month 36, highlighting that patients with PR may benefit from careful monitoring.

Mean serum creatinine remained stable at normal or close to normal levels between Years 1 to 3 for those in CR or PR, (for both the ordinal mALMS and mBLISS-LN criteria); serum creatinine levels as measured at 24 months tended to persist over the following year. In patients with no remission at 24 months (for both the ordinal mALMS and mBLISS-LN criteria), serum creatinine levels remained elevated, yet decreased slightly between Years 1 and 3, suggesting a possible improvement over time.

The Hopkins Lupus Cohort is a prospective, longitudinal study of disease activity, organ damage and quality of life in patients with SLE (20). The large LN cohort size (>500 patients) together with the extensive recording of key outcomes, provides a rich source of data for investigating the clinical importance of achieving renal remission according to various definitions. There are several limitations to this study, however. The Hopkins Lupus Cohort is a single center study, which may limit the generality of these results. The sample size meant that the power to detect small differences across groups (e.g. no remission vs PR) was limited. Retrospectively applying clinical trial endpoint criteria to these real-world data may have been associated with some misclassification. Finally, renal response was assessed at 24 months post lupus nephritis biopsy date in the current study. Future studies could explore the association between renal response measured at earlier (for example at 6, 12 and 18 months) and later time points (for example at 36 months) to inform the selection of the optimal time point to assess remission status.

Further observational studies in a larger multicenter population are required to confirm these findings and to further assess the clinical relevance of PR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by GSK. The Hopkins Lupus Cohort was funded by NIH AR 43727. Medical writing assistance was provided by Louisa Pettinger, PhD, and Jennie McLean, PhD, of Fishawack Indicia Ltd, and was funded by GSK.

Footnotes

Author conflict of interest disclosures:

JED: Shareholder of GSK; employee of GSK at the time of study; current employee of Eli Lilly and Company Ltd

QF: Shareholder of GSK; employee of GSK

BJ: Shareholder of GSK; employee of GSK

SR: Employee of GSK; student at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

DR: Shareholder of GSK; employee of GSK

LSM: None

MP: Consultant for and recipient of research grants from GSK

References

- 1.Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J, Sebastiani GD, Gil A, Lavilla P, et al. Morbidity and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus during a 10-year period: a comparison of early and late manifestations in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2003;82:299–308. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000091181.93122.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernatsky S, Boivin JF, Joseph L, Manzi S, Ginzler E, Gladman DD, et al. Mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2550–7. doi: 10.1002/art.21955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sprangers B, Monahan M, Appel GB. Diagnosis and treatment of lupus nephritis flares--an update. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8:709–17. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maroz N, Segal MS. Lupus nephritis and end-stage kidney disease. Am J Med Sci. 2013;346:319–23. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31827f4ee3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yap DY, Tang CS, Ma MK, Lam MF, Chan TM. Survival analysis and causes of mortality in patients with lupus nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:3248–54. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inda-Filho A, Neugarten J, Putterman C, Broder A. Improving outcomes in patients with lupus and end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2013;26:590–6. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furie R, Nicholls K, Cheng TT, Houssiau F, Burgos-Vargas R, Chen SL, et al. Efficacy and safety of abatacept in lupus nephritis: a twelve-month, randomized, double-blind study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:379–89. doi: 10.1002/art.38260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rovin BH, Furie R, Latinis K, Looney RJ, Fervenza FC, Sanchez-Guerrero J, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in patients with active proliferative lupus nephritis: The lupus nephritis assessment with rituximab study. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1215–26. doi: 10.1002/art.34359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinclair A, Appel G, Dooley MA, Ginzler E, Isenberg D, Jayne D, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil as induction and maintenance therapy for lupus nephritis: Rationale and protocol for the randomized, controlled Aspreva Lupus Management Study (ALMS) Lupus. 2007;16:972–80. doi: 10.1177/0961203307084712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Appel GB, Contreras G, Dooley MA, Ginzler EM, Isenberg D, Jayne D, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus cyclophosphamide for induction treatment of lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1103–12. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008101028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Houssiau FA, Vasconcelos C, D'Cruz D, Sebastiani GD, Garrido Ed Ede R, Danieli MG, et al. Immunosuppressive therapy in lupus nephritis: the Euro-Lupus Nephritis Trial, a randomized trial of low-dose versus high-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2121–31. doi: 10.1002/art.10461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wofsy D, Hillson JL, Diamond B. Comparison of alternative primary outcome measures for use in lupus nephritis clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1586–91. doi: 10.1002/art.37940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen YE, Korbet SM, Katz RS, Schwartz MM, Lewis EJ. Value of a complete or partial remission in severe lupus nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:46–53. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03280807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcon GS, Gordon C, Merrill JT, Fortin PR, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2677–86. doi: 10.1002/art.34473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dall'Era M, Cisternas MG, Smilek DE, Straub L, Houssiau FA, Cervera R, et al. Predictors of long-term renal outcome in lupus nephritis trials: lessons learned from the Euro-Lupus Nephritis cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:1305–13. doi: 10.1002/art.39026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bose B, Silverman ED, Bargman JM. Ten Common Mistakes in the Management of Lupus Nephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63:667–76. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16:31–41. doi: 10.1159/000180580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gladman D, Ginzler E, Goldsmith C, Fortin P, Liang M, Urowitz M, et al. The development and initial validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology damage index for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:363–9. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fangtham M, Petri M. 2013 update: Hopkins lupus cohort. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2013;15:360. doi: 10.1007/s11926-013-0360-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.