Abstract

Objective

Clinical heterogeneity is a key challenge to understanding suicidal risk, as different pathways to suicidal behavior are likely to exist. We aimed to identify such pathways by uncovering latent classes of late-life depression cases and relating them to prior and future suicidal behavior.

Methods

Data was collected from 09/2011-09/2015. We examined distinct associations of clinical and cognitive/decision-making factors with suicidal behavior in 194 older (50+) non-demented, depressed, elderly; 57 non-psychiatric controls provided benchmark data. The DSM-IV was used to establish diagnostic criteria. We identified multivariate patterns of risk factors defining clusters based on personality traits, perceived social support, cognitive performance and decision-making in an analysis blind to participants' history of suicidal behavior. We validated these clusters using past and prospective suicidal ideation and behavior.

Results

Of five clusters identified, three were associated with high risk for suicidal behavior: (1) cognitive deficits, dysfunctional personality, low social support, high willingness to delay future rewards, overrepresentation of high-lethality attempters; (2) high-personality-pathology (i.e. low self-esteem), minimal or no cognitive deficits, overrepresentation of low-lethality attempters and ideators; (3)cognitive deficits and inability to delay future rewards, similar distribution of high- and low-lethality attempters. There were significant between-cluster differences in number (p<0.001) and lethality (p=0.002) of past suicide attempts, as well as in the likelihood of future suicide attempts (p=0.010, 30 attempts by 22 participants, two fatal) and emergency psychiatric hospitalizations to prevent suicide (p=0.005, 31 participants).

Conclusions

Three pathways to suicidal behavior in old age were found, marked by (1) very high levels of cognitive and dispositional risk factors suggesting a dementia prodrome, (2) dysfunctional personality traits, (3) impulsive decision-making and cognitive deficits.

Keywords: Late-life, suicide, cluster analysis, predictive validation, decision-making, cognition

Introduction

Suicidal behavior emerges from a confluence of multiple risk factors, e.g., depression, personality characteristics, cognitive and decision-making deficits, and lack of social support. However, when examined individually, these factors have low specificity. Most older adults who attempt suicide or die by suicide suffer from depression 1, 2, but only a minority of depressed individuals contemplate suicide, and even fewer transition to suicidal behavior. Among the subset of depressed individuals who do attempt suicide there is also considerable heterogeneity. For example, studies have uncovered temperamental heterogeneity, suggesting that there may exist various “suicidal-risk personalities”3.In the present study we aimed to identify clusters of characteristics that confer suicidal behavior risk and may form the bases for distinct pathways to suicidal behavior.

While earlier accounts of the stress-diathesis model 4emphasized the role of impulsivity, accumulating evidence suggests that only a subgroup of people who engage in suicidal behavior is impulsive 5, 6and this proportion is lower in old age7. What might characterize suicidal individuals with low levels of impulsivity? There is a large body of evidence indicating that cognitive deficits are associated with suicidal thoughts and behavior8, 9. One pathway to suicide may thus be characterized by late-onset suicidal behavior where age-related cognitive decline or prodromal dementia 10-13 interact with dispositional and environmental factors. Another pathway maybe marked by decision-making deficits 14-16 seen in real life and in the laboratory in a subgroup of suicide attempters, accompanied by different levels of cognitive impairment12, 15-21 and impulsivity.

In contrast to predominantly early-onset, low-lethality suicide attempts in borderline personality disorder, cognitive impairments are most consistently associated with medically-serious attempts 17, 21, 22, that most closely approximate death by suicide, and are more prevalent in older age 23.Personality pathology, if present in this subgroup, may be characterized by life-long patterns of limited social interactions24.

Our longitudinal study of attempted suicide in late-life enables us to examine the validity of these pathways. We selected potential risk variables suggested by the Mann stress-diathesis model 4 as well as dispositional measures including interpersonal functioning 25.We included measures of cognitive performance 17, 26 decision competence 14, different facets of impulsivity 27-29, and social support 30.

We examined the multivariate patterns of risk factors to identify clusters of individuals based on their personality/social support and cognitive/decision-making profiles, without including psychiatric diagnoses or suicidality. Then, we provided predictive validation of this categorization based on the individuals' suicidal ideation and behavior both prior to baseline assessment and during the follow-up period.

Methods

Sample and Procedures

Sample

Two-hundred and fitfty-one older adults, 194 of whom were depressed, (age range: 50-87, M=66.7, SD=8.0) were recruited to participate in a case-control longitudinal study of late-life suicidal behavior (R01 MH085651)from 06/2010-09/2015, and provided written informed consent as required by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Our recruitment strategy was to oversample those who have risk factors for suicidal behavior, such as past history of suicide attempt and suicidal ideation. Our primary recruitment source for attempters and ideators was geriatric psychiatric units. Given the high proportion of our sample coming from an inpatient psychiatric facility, the participants were more likely to be acute, have more comorbidities, and be more similar to participants who die by suicide. Of the 194 depressed, 50 had no lifetime history of suicidal behavior or ideation, 46 contemplated suicide, and 98 had a suicide attempt. Suicide attempters (SA) made a self-injurious act with the intent to die; 49 made high-lethality attempts and 49 made low-lethality attempts. Medical seriousness was assessed using the Beck Lethality Scale (BLS) 31. For participants with multiple attempts, data for the highest lethality attempt is presented. High-lethality attempters [HL] scored > 4 on the BLS for an attempt needing treatment in medical or surgical units or emergency departments, whereas low-lethality attempters [LL] incurred no significant medical damage. Suicide ideators [I] endorsed suicidal ideation with a plan, as assessed using the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation 32, but had no history of suicide attempt. Non-suicidal depressed controls [DC] had no history of suicide attempt or suicidal ideation. Participants were diagnosed with unipolar non-psychotic major depression using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders 33. Current depression severity was measured by the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HDRS)34.

We also assessed 57 demographically-matched non-depressed controls (healthy controls; HC), as a benchmark group and to calculate standardized cognitive scores, but they were not included in any analyses. They had no lifetime history of mental health treatment and no lifetime diagnosis of DSM-IV axis I disorder.

We excluded individuals with clinical dementia (score < 24 on the Mini-Mental State Examination 35, and those with a history of neurological disorder, delirium, or sensory disorder that preclude neuropsychological testing.

Characterization

Global cognitive ability was assessed with the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (DRS)36, Cognitive control, with the Executive Interview (EXIT)37, and premorbid IQ with the Wechsler Adult Reading Test38.

Decision-making

Decision competence was assessed using two subscales of the Adult Decision Competence task: Resistance to Framing and Resistance to Sunk Cost (ADMC) 39, and Delay discounting with the Monetary Choice Questionnaire (MCQ)40.

Dispositional factors

We measured negative urgency (UPPS Negative Urgency subscale41) and impulsive/careless social problem-solving style (Social Problem Solving Inventory Impulsive/Carelessness subscale42). We assessed personality functions and different aspects of social support with the perceived burdensomeness scale43 and the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL) Self-esteem and Belongingness subscales44.

Social support

Perceived availability of practical support was assessed with the ISEL Tangible Support subscale. Items assess different aspects of tangible support, e.g., if needed, do you have somebody to take you to the hospital, lend you a car for a few hours, lend you $100, stay with you in an emergency.

A more detailed characterization of the assessments can be found in the Supplementary materials.

Data Analysis

Variables with inherently non-Gaussian distributions, namely, the MCQ score, were log-transformed. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the four depressed groups on the cognitive and personality/social support measures, as well as some psychiatric scales and demographic variables. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using Tukey's HSD method for adjustment. Summary statistics for the HC group are also reported for comparison but were not included in statistical tests.

Prior to the cluster analysis, all the scales were recoded, so that higher values on a scale corresponded to higher risk. Z-scores were calculated for all measures using the average and standard deviation of the healthy controls.

To identify distinct risk profiles among the patients, we performed a cluster analysis on the eleven measures identified above, and also included the HDRS. HC participants were excluded to avoid assumptions about the homology of subgroups among psychiatrically healthy vs. depressed individuals, as were 5 subjects with missing MCQ scores. Using the remaining 189 subjects, we performed k-mean cluster analysis (“kmeans” function in R 45), with default parameter choices and numerical method 46, with k = 2 to 7 clusters. We selected k=5 because it was the smallest number of clusters for which the between-cluster variability, expressed as a proportion of the total variability, exceeded our preset criterion of 30%. We omitted attempter status, suicidal ideation, lethality in the derivation of the clusters to avoid circularity in the identification of clusters.

We provided qualitative and quantitative summaries of each cluster based on the cluster averages for each measure used to derive them. Association between suicide attempt history and cluster membership was tested using Fisher's exact test, and post-hoc comparisons compared cluster membership of each suicidal group to that of the DC group using Holm's method of adjustment for multiple comparisons. We compared average scores of past suicide attempt lethality, baseline suicidal ideation, and the planning subscale of the suicide intent scale. We prospectively assessed suicide attempts or emergency psychiatric hospitalizations during the follow-up period, and used these data to test the predictive validity of our clusters by comparing the probability of suicide attempt between clusters using survival analysis, specifically the log-rank test, and post-hoc cluster comparisons, adjusted using the Bonferroni method. The (possibly censored) number of emergency psychiatric hospitalizations between clusters during the follow-up period was compared using the Kruskal test, followed by pairwise comparisons using Wilcoxon tests, adjusted as above.

Results

Demographic, clinical, cognitive and personality measures across groups and mean differences therein are reported in Supplementary eTables 1 and 2.

Cluster analysis

Tables 1 and 2 report demographic, clinical, cognitive and personality measures by clusters. In the selected cluster model (k = 5), the smallest cluster size was n1 = 13 and the largest n2 = 71. There were significant differences across the clusters on every measure(all ps<0.001, after adjustment for multiple testing).

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics by Clusters.

| Healthy Controla (n=57) | Cluster 1 (n=13) | Cluster 2 (n=71) | Cluster 3 (n=30) | Cluster 4 (n=49) | Cluster 5 (n=26) | F / Chi-Squared | P | Post-hocb | |||||||

| Mean|SD(Percentage) | |||||||||||||||

| Age | 67.0 | 6.8 | 69.2 | 11.4 | 66.9 | 7.2 | 72.2 | 8.3 | 62.9 | 5.9 | 66.1 | 7.6 | 7.5 | 0.0 | 3-2,4,5 2-4 |

| Gender (Male) | 28 | 49% | 40% | 50% | 50% | 40% | 50% | 0.7 | |||||||

| Caucasian | 50 | 88% | 90% | 90% | 90% | 90% | 70% | 0.1 | |||||||

| Education (Years) | 15.2 | 2.8 | 12.0 | 3.1 | 15.3 | 2.9 | 12.9 | 2.8 | 14.0 | 2.2 | 13.0 | 2.3 | 8.1 | 0.0 | 2-1,3,5 |

| SES per-capitac | 29.6 | 15.4 | 21.3 | 19.9 | 25.7 | 21.5 | 15.2 | 17.6 | 16.3 | 12.8 | 22.8 | 20.5 | 12.2 | 0.0 | 2-3,4 |

| Hamilton depression scale (without suicide item) d | 2.4 | 1.9 | 24.1 | 6.2 | 16.3 | 3.9 | 18.5 | 5.9 | 21.4 | 3.9 | 17.9 | 5.0 | 13.8 | 0.0 | 1-2,3,5 2-4 3-5 |

| IQ | 108.6 | 12.2 | 95.2 | 12.5 | 110.0 | 14.8 | 97.4 | 18.9 | 105 | 14.1 | 97.5 | 18.2 | 6.1 | 0.0 | 2-1,3,5 |

| Age of Onset of First Depressive Episode | N/A | N/A | 55.6 | 20.5 | 50.5 | 19.9 | 47.4 | 22.4 | 37.7 | 19.1 | 39.5 | 22.0 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 4-1,2 |

| Physical Illness Burdend | 6.6 | 3.9 | 9.5 | 3.5 | 8.7 | 4.4 | 10.7 | 3.6 | 8.2 | 3.6 | 8.1 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 0.1 | |

| Ideation (Current) d | 0.2 | 0.1 | 20.2 | 6.3 | 9.4 | 11.4 | 17.5 | 10.5 | 15.6 | 10.9 | 11.7 | 9.9 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 2-1,3,4 |

| Ideation (Lifetime) d | 0.2 | 0.1 | 21.9 | 7.2 | 11.9 | 12.0 | 21.1 | 10.3 | 22.5 | 9.0 | 17.1 | 12.3 | 8.8 | 0.0 | 2-1,3,4 |

| Anxiety Disorder (Current) | 0% | 60% | 40% | 10% | 60% | 40% | 0.0 | 3-1,2,4 | |||||||

| Anxiety Disorder (Lifetime) | 1.8% | 70% | 50% | 20% | 60% | 40% | 0.0 | 1-3,4 | |||||||

| Substance Abuse (Current) | 0% | 20% | 10% | 10% | 10% | 20% | 0.1 | ||||||||

| Substance Abuse (Lifetime) | 0% | 40% | 30% | 40% | 40% | 50% | 0.7 | ||||||||

| History of attempt at baseline | NA | 76% | 32% | 60% | 51% | 50% | 13.197 | 0.0 | 1-2 | ||||||

Please note that ANOVA was only performed in the depressed participants, HC group is only included as a benchmark.

Post-hoc comparisons were done to communicate significant between-cluster differences

SES data is reported in thousands.

Higher scores indicative of more pathology.

Table 2. Cognitive, Decision-making, and Personality Characteristic and Social Support by Clusters.

| Healthy Controla (n=57) | Cluster 1 (n=13) | Cluster 2 (n=71) | Cluster 3 (n=30) | Cluster 4 (n=49) | Cluster 5 (n=26) | F / Chi-Squared | P | Post-hocb | |||||||

| Mean|SD(Percentage) | |||||||||||||||

| Global Cognition | 138.3 | 2.8 | 124.7 | 8.1 | 136.0 | 3.9 | 126.6 | 6.6 | 136.1 | 3.9 | 133.2 | 4.5 | 34.3 | 0.0 | 1-2,4,5 3-2,4,5 |

| Cognitive Controlc | 5.7 | 3.1 | 14.7 | 5.3 | 5.7 | 3.1 | 11.5 | 3.1 | 6.6 | 2.7 | 8.5 | 3.5 | 33.6 | 0.0 | 1-2,3,4,5 3-2 5-2,3 |

| Resistance to Framing | 4.3 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 0.7 | 4.4 | 0.4 | 4.1 | 0.6 | 4.1 | 0.6 | 2.9 | 0.8 | 37.4 | 0.0 | 1-2,3,4,5 2-4 5-2,3,4 |

| Resistance to Sunk Cost | 4.8 | 0.6 | 4.5 | 0.6 | 4.8 | 0.6 | 4.0 | 0.9 | 4.3 | 0.7 | 4.5 | 0.7 | 8.8 | 0.0 | 2-3,4 |

| UPPS Negative Urgencyc | 18.9 | 4.3 | 38.4 | 7.5 | 23.5 | 6.0 | 26.3 | 8.2 | 31.7 | 6.5 | 28.2 | 6.4 | 20.1 | 0.0 | 1-2,3,4,5 2-4,5 3-4 |

| Delay Discountingd | -5.4 | 1.2 | -6.0 | 1.8 | -5.0 | 1.4 | -3.6 | 1.1 | -4.3 | 1.1 | -4.8 | 1.2 | 10.2 | 0.0 | 3-1,2,5 4-1 |

| Impulsive Carelessnessc | 86.0 | 9.3 | 123.2 | 13.0 | 92.7 | 12.6 | 86.9 | 7.0 | 107.4 | 16.7 | 108.8 | 15.2 | 28.1 | 0.0 | 1-2,3,4,5 2-4,5 5-3,4 |

| Perceived Burdensomenessc | 0.2 | 0.5 | 5.2 | 3.4 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 4.7 | 3.3 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 2-1,3,4 5-1,3,4 |

| Self-Esteem | 9.4 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 6.6 | 2.5 | 6.3 | 2.4 | 3.1 | 2.0 | 6.4 | 2.3 | 25.4 | 0.0 | 1-2,3,5 4-2,3,5 |

| Belonging | 10.5 | 1.5 | 6.8 | 2.2 | 8.3 | 2.5 | 7.5 | 3.1 | 4.8 | 2.8 | 8.6 | 2.5 | 14.9 | 0.0 | 4-2,3,5 |

| Practical Support | 11.0 | 1.5 | 5.6 | 3.5 | 9.9 | 1.9 | 7.4 | 2.6 | 5.4 | 3.0 | 8.7 | 2.4 | 27.0 | 0.0 | 2-1,3,4 4-3,5 5-1 |

Please note that ANOVA was only performed in the depressed participants, HC group is only included as a benchmark.

Post-hoc comparisons were done to communicate significant between-cluster differences

Higher scores indicative of more pathology

For this assessment, both extremely high and extremely low scores are indicative of maladaptive decision making

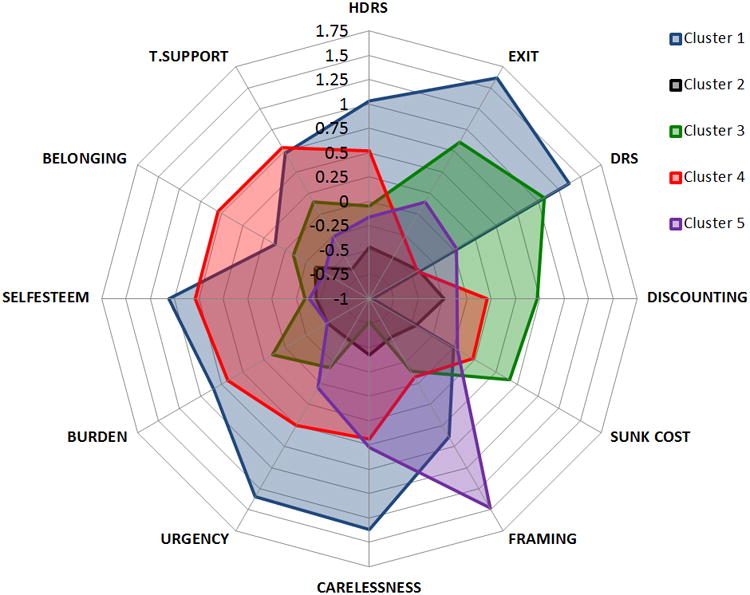

Inspection of the profile plot (see Figure 1) and univariate comparisons (Tables 1 and 2) revealed unique profiles for each of the five clusters, that also corresponded to clinical presentations (see Supplementary Material for case examples).

Figure 1. Cognitive and Personality Characteristics and Social Support by Cluster.

aPlease note that all the scales were aligned in the risk direction, so that higher values on a scale were associated with higher risk of psychopathology e.g., high levels of depression, cognitive deficits, low tangible social support.

bAbbreviations: Burden: Perceived Burdensomeness Scale; Carelessness: Social Problem Solving Inventory Impulsive/Carelessness subscale; DRS: Mattis Dementia Rating Scale; Discounting: Monetary Choice Questionnaire; EXIT: Executive Interview; Framing: Adult Decision Competence Scale Resistance to Framing Subscale; HDRS: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; Sunk cost: Adult Decision Competence Scale Resistance to Sunk Cost subscale; Self-Esteem: Interpersonal Support Evaluation List, Self-esteem subscale; Belonging: Interpersonal Support Evaluation List, Belongingness subscale; T Support: Interpersonal Support Evaluation List, Lack of Tangible Social Support; Urgency: UPPS Negative Urgency Subscale.

Cluster 1 (C-1):Marked cognitive deficits with serious psychopathology

(n=13, 7% of total sample), is characterized by severe cognitive deficits as indicated by poorer cognitive control (EXIT) than all the other clusters and poorer global cognition (DRS) than clusters 2, 4 and 5, combined with severe depression and higher levels of dispositional risk factors. These individuals displayed certain facets of impulsivity, as indicated by very high scores on the SPSI Impulsive/Careless and the UPPS Negative Urgency subscales. However, they were willing to wait for delayed rewards, displaying extremely low levels of discounting compared to the HC group (N=57). They reported low self-esteem, perceived themselves as a burden, and reported limited tangible social support.

Cluster 2 (C-2):Intact

(N=71, 37% of total sample) is characterized by the lowest depression scores and almost uniformly low risk scores on both cognitive and dispositional risk factors.

Cluster 3 (C-3):Poor decision-making and moderate cognitive deficits

(N=30, 16% of total sample) is characterized by pronounced deficits in global cognition (less severe than C-1, but worse than all the other clusters) and cognitive control. They also demonstrated the highest levels of delay discounting and susceptibility to sunk cost bias.

Cluster 4 (C-4):Dysfunctional personality

(N=49, 26% of total sample), unlike C-1, displays no cognitive deficits, but is characterized by the lowest levels of belonging and tangible social support as well as high levels of perceived burdensomeness and impulsivity.

Cluster 5 (C-5):Framing deficits

(N=26, 14% of total sample) is characterized by susceptibility to framing effects, and impulsive/careless social problem-solving style. These individuals were otherwise intact as indicated by relatively high self-esteem, lack of perceived burden someness, low depression scores, and good social support.

To test whether age or education differences among clusters explained cluster differences in global cognition (DRS scores), we fit two ANCOVA models adjusted by age and education, respectively. Cluster differences remained significant after adjustment (p<0.0001), while age also had a significant adjusted effect (F=17.18, df=1,183 p<0.0001), but education did not (F=0.07, df=1,183, p= 0.7989). We conclude that cluster differences in cognition are not all due to age or education differences.

The identified clusters reflect the suicide risk profiles, including both the states and the traits, of the subjects at baseline. We did not adjust for age before clustering based on the full sample to avoid the assumption that every cluster ages the same way. Our data point to the possibility that accelerated and/or pathological aging that effect cognition/decision-making is part of the suicidal diathesis in old age.

Retrospective validation: History of suicide attempts and suicidal ideation by cluster

Although variables capturing suicidal behavior and ideation were omitted when deriving the clusters, cluster composition nonetheless differed based on study group (Fisher's exact test p<0.001). When the combined attempter group was contrasted with non-attempters (Fisher test p<0.001), post-hoc pairwise comparisons showed that differences were limited to clusters 1-2 and clusters 2-3. Distributions of HL and LL attempters also differed across groups (p=0.021 and p<0.001, respectively.)

C-1 did not contain any DC participants. HL attempters compared to DC, were only overrepresented in C-1 compared to the composition of C-2 (C-2 vs.C-1: OR=0,95%CI:0.00-0.38, adjusted p=0.003). The proportion of LL attempters, when compared to DC, was higher in C-3 and C-4, but not in C-1 (C-3 vs. C-2 OR=11.40, 95%CI: 2.46- 65.75, adj. p=0.002; C-4 vs. C-2: OR=19.13, 95%CI: 4.99-89.89, adj. p<0.001; C-2 vs.C-1 OR=0.00, 95%CI: 0.00-0.40, adj. p=0.007).In C-4, compared to C-3, ideators were over-represented compared to DC(OR=797, 95%CI: 2.27-33.33, adj. p=0.002). Results were similar when continuous lethality scores were compared between clusters. For a depiction of the retrospective validation, please see Supplementary eFigure 1.

Clusters differed in the number of past suicide attempts (Kruskal-Wallis test χ2=25.9, df=4, p<0.001): C-2 contained the lowest proportion of subjects with multiple past attempts. Severity of ideation differed between clusters (F=8.76, df=4,184, p<0.001), such that C-2 ideation scores were significantly lower than those of C-1, C-3, and C-4.

Predictive validation: Suicide attempt and emergency hospitalizations to prevent suicide by cluster

We observed a total of 30 suicide attempts (two fatal) in 22 participants during the follow-up period (mean duration of follow-up 30±18 months).Two participants had two attempts and three had three attempts. The majority of these incident attempts were made by participants with a prior history of suicide attempt. There were four participants classified as ideators at baseline who made an attempt during the follow-up period (had their “first ever” suicide attempt). There were significant between-cluster differences in the incidence of suicide attempts during the follow-up period using the log-rank test (p=0.010), with post-hoc pairwise differences showing fewer follow-up attempters in C-2 (3%) than C-1 (31%, adjusted p=0.002), C-3 (20%, adjusted p=0.012), and C-4 (14%, adjusted p=0.044), in each C-1 and C-3 one fatal suicide occured. The number of emergency psychiatric admissions during follow-up also differed by cluster (p=0.005), with significantly fewer re-admissions in C-2 than C-1 (post-hoc Wilcoxon test adjusted p=0.029), or C-3 (adjusted p=0.013). We also assessed the presence and severity of suicidal ideation during the follow-up with in-person or phone assessments upto four years. Worst ideation scores at any time during the follow up differed significantly (p<0.001) between clusters, with C-2 having lower scores than C-4 (post-hoc adjusted p<0.001) and C-5 (adjusted p=0.024), but not C-1 and C-3, showing a different pattern than for suicide attempts and hospitalizations.

Discussion

To identify distinct pathways toward suicidal behavior, we used a data-driven approach which relied on self-report, clinician-administered diagnostic assessments, cognitive performance tests, and complex decision competence tasks to classify a large sample of depressed individuals into homogeneous clusters.

Our findings are consistent with the hypothesis that distinct pathways toward suicidal behavior exist in the second half of life (C-1, C-3 and C-4). Providing external validation, there were between-cluster differences in the number and lethality of suicide attempts prior to baseline, and during the average 30-month follow-up period. Outcome prediction is the best test of classifications in psychiatry 47.C-1 and C-3 had the highest proportions of subjects with one or more incident suicide attempts (31% and 20% respectively, one fatal in each) contrasted with only 3% of participants in C-2.

Perhaps of greatest clinical interest is Cluster 1, which contained the highest proportion of high-lethality attempters and strongly predicted re-attempt. Its members displayed severe cognitive deficits, even though the study excluded participants diagnosed with dementia. What underlying factors may account for this putative pathway? We speculate that the cognitive profile of C-1 participants corresponds most closely to early dementia. Behavioral prodromes characterized by mood and personality change and poor decision-making are common in fronto temporal dementia and frontal variant of Alzheimer's disease. Consistent with this notion, individuals in C-1 had a later age of depression onset (≈18 years later than C-4). Supporting this theory of prodrome, a nationwide Taiwanese study reported that attempted suicide in late-life predicted subsequent dementia 10. Given that our analysis is based on a single cognitive assessment, we cannot rule out the possibility that these cognitive deficits are lifelong 48, however many C-1 members performed in the early dementia range.

Less clear is the status of individuals in C-3, who were equally likely to have a history of low- and high-lethality suicide attempts, and a high reattempt rate. Some of them may also fall into the prodromal dementia category, as their global cognitive performance was not much better than C-1, but the average age of depression onset was earlier in C-3 than in C-1.They were most susceptible to sunk cost bias, which has been linked to facets of emotional dyscontrol such as anger, rumination and impulsivity 49. They also displayed an exaggerated preference for immediate vs. delayed rewards. This combination of short-sightedness, lack of perspective, and limited cognitive resources would be consistent with a failure to anticipate that suffering during a suicidal crisis is likely time-limited, as well as the finality of the consequences of a completed suicide.

Individuals in C-4 had the earliest age of onset of depression, and high levels of dispositional risk factors (especially poor interpersonal functioning) in the setting of intact cognition. This constellation of chronic interpersonal dysfunction, perceived abandonment and suicidal behavior suggests borderline personality traits. This conclusion is supported by the over-representation of low-lethality suicide attempters in C-4.

In accordance with our previous findings in a smaller sample 27, individuals in C-3 and C-4 display an exaggerated preference for immediate rewards, whereas those in C-1 are unusually willing to wait for larger rewards. High delay discounting is broadly associated with impulsivity and seen in disorders characterized by poor impulse control and short-sighted choices (addiction, gambling, bulimia, borderline and antisocial personality). In contrast, an extreme ability to delay gratification was observed in obsessive-compulsive personality disorders (OCPD) and aneroxia nervosa 50. We speculate that what may be in common between OCPD, anorexia and serious suicidal behavior is the neglect of the opportunity cost 51, 52, or the rewards that could be obtained with an alternative course of action. This neglect could manifest in a single-minded dedication to the pathological behavior at the expense of better alternatives.

We are cautious interpreting C-5. Susceptibility to framing (responding to superficial features of how a problem is presented) was its defining characteristic, perhaps highlighting a distinct contribution of this factor14.

Most of the research to date has focused on identification of risk factors for suicide contemplation.53, 54 A number of recent reviews55, 56 concluded that risk factors for contemplation of suicide differ from risk factors for the transition from ideation to attempt. Thus, it is not unanticipated that Cluster 4 participants who had the highest level of personality based risk factors, such as low self-esteem, subjective lack of belonging, feeling like a burden, but had no cognitive deficits showed high levels of ideation during the follow up while their (re) attempt rate was relatively low. These participants seem to fit the profile of borderline personality disorder and many of them had chronic high level of suicidal ideation.

Research that has investigated risk factors for suicide attempt has mainly based the classification of attempters on attempt characteristics.57-60 For example, Lopez-Castroman and colleagues classified suicide attempters into three groups (“impulsive-ambivalent”, “well-planned”, “frequent”) 58. However, as 1/3-1/2 of older adults who die by suicide do not have a previous attempt, prediction based on features other than attempt characteristics has high clinical value 2. Strengths of this study include sampling across the spectrum of suicide risk (from depressed patients with no lifetime history of even suicidal ideation, to high-lethality attempters), prospective ascertainment of suicidal behavior and a detailed characterization of both risk factors and suicidal behavior itself.

Limitations

Subgroups identified here require out-of-sample validation. Our findings may not be generalizable to other age groups. In addition, as dementia is more prevalent with increasing age, there were fewer older participants who were potentially eligible for participation given that clinical dementia precluded participation.

In summary, we have found that three putative subgroups of depression patients are at the highest risk for subsequent suicidal behavior: one characterized by concurrent high levels of cognitive impairment and personality pathology, one defined by short-sighted decision-making and moderate cognitive deficits, and a third characterized by interpersonal dysfunction.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Points.

As suicidal behavior in older adulthood is heterogeneous, pathways differentiating risk profiles need to be identified.

This study was able to identify three pathways: one is characterized by late-onset depression and cognitive deficits resembling a dementia prodrome, another is characterized by early-onset depression and prominent personality pathology, and a third is defined by short-sighted decision-making and moderate cognitive deficits.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA (MHR01MH085651to K.Sz, MH R01 MH100095 to A.D, and UL1 TR001857.) The funding agency had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

We would like to acknowledge Laura B. Kenneally B.A.a for editorial assistance and data collection, Maria G. Alessi B.S.a and Amanda L. Collier B.S.a for data collection, Jonathan Wilson B.S.a for graphical assistance.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: None of the authors or persons acknowledged has a conflict of interest to disclose.

Previous presented: Some of the results presented at Society of Biological Psychiatry annual meeting, San Diego, CA, USA, May 18-21, 2017

References

- 1.Conwell Y, Brent D. Suicide and aging I: patterns of psychiatric diagnosis. International psychogeriatrics. 1995;7(2):149–164. doi: 10.1017/s1041610295001943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waern M, Runeson BS, Allebeck P, et al. Mental disorder in elderly suicides: a case-control study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002 Mar;159(3):450–455. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engström G, Alsén M, Gustavsson P, Schalling D, Träskman-Bendz L. Classification of suicide attempters by cluster analysis: A study of the temperamental heterogeneity in suicidal patients. Personality and individual differences. 1996;21(5):687–695. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mann JJ, Waternaux C, Haas GL, Malone KM. Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1999 Feb;156(2):181–189. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keilp JG, Gorlyn M, Oquendo MA, et al. Aggressiveness, not impulsiveness or hostility, distinguishes suicide attempters with major depression. Psychological Medicine. 2006 Dec;36(12):1779–1788. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keilp J, Beers S, Burke A, et al. Neuropsychological deficits in past suicide attempters with varying levels of depression severity. Psychological medicine. 2014;44(14):2965–2974. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGirr A, Renaud J, Bureau A, Seguin M, Lesage A, Turecki G. Impulsive-aggressive behaviours and completed suicide across the life cycle: a predisposition for younger age of suicide. Psychological Medicine. 2008 Mar;38(3):407–417. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keilp JG, Gorlyn M, Russell M, et al. Neuropsychological function and suicidal behavior: attention control, memory and executive dys function in suicide attempt. Psychological Medicine. 2013;43(3):539–551. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lara E, Olaya B, Garin N, et al. Is cognitive impairment associated with suicidality? A population-based study. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;25(2):203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tu YA, Chen MH, Tsai CF, et al. Geriatric suicide attempt and risk of subsequent dementia: a nationwide longitudinal follow-up study in Taiwan. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2016;24(12):1211–1218. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haw C, Harwood D, Hawton K. Dementia and suicidal behavior: a review of the literature. International Psychogeriatrics. 2009 Jun;21(3):440–453. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209009065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gujral S, Ogbagaber S, Dombrovski AY, Butters MA, Karp JF, Szanto K. Course of cognitive impairment following attempted suicide in older adults. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1002/gps.4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erlangsen A, Zarit SH, Conwell Y. Hospital-diagnosed dementia and suicide: a longitudinal study using prospective, nationwide register data. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2008;16(3):220–228. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181602a12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szanto K, de Bruin WB, Parker AM, Hallquist MN, Vanyukov PM, Dombrovski AY. Decision-making competence and attempted suicide. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2015;76(12):1590–1597. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m09778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jollant F, Bellivier F, Leboyer M, et al. Impaired decision making in suicide attempters. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005 Mar;162(2):304–310. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark L, Dombrovski AY, Siegle GJ, et al. Impairment in risk-sensitive decision-making in older suicide attempters with depression. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26(2):321–330. doi: 10.1037/a0021646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keilp JG, Sackeim HA, Brodsky BS, Oquendo MA, Malone KM, Mann JJ. Neuropsychological dysfunction in depressed suicide attempters. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(5):735–741. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richard-Devantoy S, Jollant F, Kefi Z, et al. Deficit of cognitive inhibition in depressed elderly: a neurocognitive marker of suicidal risk. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;140(2):193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richard-Devantoy S, Berlim M, Jollant F. A meta-analysis of neuropsychological markers of vulnerability to suicidal behavior in mood disorders. Psychological medicine. 2013:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dombrovski AY, Butters MA, Reynolds CF, 3rd, et al. Cognitive Performance in Suicidal Depressed Elderly: Preliminary Report. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008 Feb;16(2):109–115. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180f6338d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richard-Devantoy S, Szanto K, Butters MA, Kalkus J, Dombrovski AY. Cognitive inhibition in older high-lethality suicide attempters. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014 Mar 12;30(3):274–283. doi: 10.1002/gps.4138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGirr A, Dombrovski AY, Butters M, Clark L, Szanto K. Deterministic learning and attempted suicide among older depressed individuals: Cognitive assessment using the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2012 Feb;46(2):226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.10.001. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Leo D, Padoani W, Scocco P, et al. Attempted and completed suicide in older subjects: results from the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study of Suicidal Behaviour. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001 Mar;16(3):300–310. doi: 10.1002/gps.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szanto K, Dombrovski AY, Sahakian BJ, et al. Social Emotion Recognition, Social Functioning, and Attempted Suicide in Late-Life Depression. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2012 Mar;20(3):257–265. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31820eea0c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joiner TE, Jr, Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Rudd MD. The interpersonal theory of suicide: Guidance for working with suicidal clients. American Psychological Association; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gujral S, Dombrovski AY, Butters M, Clark L, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Szanto K. Impaired Executive Function in Contemplated and Attempted Suicide in Late Life. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013 Feb 6; doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dombrovski AY, Szanto K, Siegle GJ, et al. Lethal Forethought: Delayed Reward Discounting Differentiates High- and Low-Lethality Suicide Attempts in Old Age. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;70(2):138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klonsky ED, May A. Rethinking impulsivity in suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2010 Dec;40(6):612–619. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.6.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibbs LM, Dombrovski AY, Morse J, Siegle GJ, Houck PR, Szanto K. When the solution is part of the problem: problem solving in elderly suicide attempters. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009 Dec;24(12):1396–1404. doi: 10.1002/gps.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, Conner KR, Eberly S, Evinger JS, Caine ED. Poor social integration and suicide: fact or artifact? A case-control study. Psychological Medicine. 2004 Oct;34(7):1331–1337. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck AT, Beck R, Kovacs M. Classification of suicidal behaviors: I. Quantifying intent and medical lethality. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1975 Mar;132(3):285–287. doi: 10.1176/ajp.132.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979 Apr;47(2):343–352. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.First M SR, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders - Patient Edition (SCID-I/P) Version 2.0. 1995 ed. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1960 Feb;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mattis S. Dementia Rating Scale. DRS Professional Manual: PAR. 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Royall DR, Mahurin RK, Gray KF. Bedside assessment of executive cognitive impairment: the executive interview. Journal of American Geriatrics Society. 1992 Dec;40(12):1221–1226. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb03646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wechsler D. Wechsler Test of Adult Reading. San Antonio, Texas: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bruine de Bruin W, Fischhoff B, Parker A. Individual Differences in Adult Decision-Making Competence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92(5):938–956. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. J Exp Psychol Gen. 1999 Mar;128(1):78–87. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whiteside S, Lynam D. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30(4):669–689. [Google Scholar]

- 42.D'Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM. Development and preliminary evaluation of the Social Problem-Solving Inventory. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;2(2):156–163. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Orden K, Witte TK, Gordon KH, Bender TW, Joiner TE. Suicidal Desire and capability for suicide: Tests of the interpersonal--psychological theory of suicidal behavior among adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(1):72–83. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brookings JB, Bolton B. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1988 Feb;16(1):137–147. doi: 10.1007/BF00906076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2015. URL http://www.R-project.org 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hartigan JA, Wong MA. Algorithm AS 136: A k-means clustering algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series C (Applied Statistics) 1979;28(1):100–108. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marquand AF, Wolfers T, Mennes M, Buitelaar J, Beckmann CF. Beyond lumping and splitting: a review of computational approaches for stratifying psychiatric disorders. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andersson L, Allebeck P, Gustafsson JE, Gunnell D. Association of IQ scores and school achievement with suicide in a 40-year follow-up of a Swedish cohort. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2008;118(2):99–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coleman MD. Sunk cost, emotion, and commitment to education. Current Psychology. 2010;29(4):346–356. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, Koffarnus MN, Gatchalian KM. Excessive discounting of delayed reinforcers as a trans-disease process contributing to addiction and other disease-related vulnerabilities: emerging evidence. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2012;134(3):287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Niv Y, Daw ND, Joel D, Dayan P. Tonic dopamine: opportunity costs and the control of response vigor. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191(3):507–520. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0502-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Green DI. Pain-Cost and Opportunity-Cost. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1894;8(2):218–229. [Google Scholar]

- 53.May AM, Klonsky ED. What Distinguishes Suicide Attempters From Suicide Ideators? A Meta-Analysis of Potential Factors. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Mental disorders, comorbidity and suicidal behavior: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Molecular psychiatry. 2009 doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. 2016 doi: 10.1037/bul0000084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klonsky ED, Qiu T, Saffer BY. Recent advances in differentiating suicide attempters from suicide ideators. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2017;30(1):15–20. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arensman E, Kerkhof AJ. Classification of attempted suicide: a review of empirical studies, 1963–1993. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1996;26(1):46–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lopez-Castroman J, Nogue E, Guillaume S, Picot M, Courtet P. Clustering suicide attempters: impulsive-ambivalent, well-planned, or frequent. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m09882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rapeli CB, Botega NJ. Clinical profiles of serious suicide attempters consecutively admitted to a university-based hospital: a cluster analysis study. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 2005;27(4):285–289. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462005000400006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Paykel E, Rassaby E. Classification of suicide attempters by cluster analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1978;133(1):45–52. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.