Abstract

Neuroimmune activation is a key feature of the pathologies of numerous psychiatric disorders including alcoholism, depression, and anxiety. Both HMGB1 and IL-1β have been implicated in brain disorders. Previous studies find HMGB1 andIL-1β form heterocomplexes in vitro with enhanced immune responses, lead to our hypothesis that HMGB1 and IL-1β heterocomplexes formed in vivo to contribute to the pathology of alcoholism. HMGB1/IL-1β heterocomplexes were prepared in vitro and found to potentiate IL-1β receptor proinflammatory gene induction compared to IL-1β alone in hippocampal brain slice culture. These HMGB1/IL-1β complexes were found to be increased in post-mortem human alcoholic hippocampus by co-immunoprecipiation. In mice, acute binge ethanol induced both HMGB1 and IL-1β in the brain and plasma. HMGB1 and IL-1β complexes were found only in mouse brain, with confocal microscopy revealing an ethanol-induced HMGB1 and IL-1β cytoplasmic co-localization. Surprisingly, IL-1β was found primarily in neurons. Studies in hippocampal brain slice culture found ethanol increased HMGB1/IL-1β complexes in the media. These studies suggest a novel neuroimmune mechanism in the pathology of alcoholism. Immunogenic HMGB1/IL-1β complexes represent a novel target for immune modulatory therapy in alcohol use disorders, and should be investigated in other psychiatric diseases that involve a neuroimmune component.

Introduction

Innate immune responses have been found to be important in the pathology of several psychiatric disorders such as alcoholism and depression (Hodes, Kana et al. 2015, Crews, Lawrimore et al. 2017). The release of endogenous Danger Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) and cytokines amplify innate immune responses through signaling at Toll-like Receptors (TLRs) and cytokine receptors respectively. Alcohol abuse causes dysregulation of the innate immune system in part through the release of endogenous TLR agonists (Crews and Vetreno 2016, Crews, Lawrimore et al. 2017). The induction of the DAMP HMGB1 is a key feature of the immune activity of alcohol. HMGB1 is induced in the brain by chronic alcohol in vitro and is also increased in the brain of postmortem human alcoholics (Crews, Qin et al. 2013, Lippai, Bala et al. 2013, Coleman, Zou et al. 2017). HMGB1 is a nuclear histone-binding protein that has been described as a master regulator of innate immunity (Castiglioni, Canti et al. 2011). Upon activation, HMGB1 translocates from the nucleus and is released, where it directly binds immune receptors TLR4 and RAGE, and facilitates the signaling of an array of other TLRs including TLR2, TLR3, TLR7 and TLR9 (Hori, Brett et al. 1995, Yanai, Ban et al. 2009, Coleman, Zou et al. 2017). Furthermore, HMGB1 has been shown to form complexes with immune molecules such as LPS, CXCL12, and IL-1β in vitro to potentiate their responses (Bianchi 2009, Hreggvidsdottir, Ostberg et al. 2009, Schiraldi, Raucci et al. 2012). Thus, HMGB1 not only modulates innate immune responses through its own activity, but by modulating responses of other immune agonists’ receptor signaling.

HMGB1 signaling is often linked with the release of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β. Both HMGB1 and IL-1β amplify immune responses and contribute to aberrant inflammation (Keyel 2014). IL-1β has also been implicated in the pathology of alcohol abuse. IL-1β mRNA levels are increased in the peripheral monocytes of alcoholics and correlate with alcohol consumption and craving (Leclercq, De Saeger et al. 2014). Chronic alcohol increases IL-1β in the cerebellum (Lippai, Bala et al. 2013) and IL-1β antagonism in the basolateral amygdala reduces alcohol self-administration (Marshall, Casachahua et al. 2016). Both HMGB1 and IL-1β release has been shown to utilize unconventional secretion mechanisms, due to their lack of conventional secretory leader sequence (Gardella, Andrei et al. 2002, Nickel and Rabouille 2009). However, it is not known whether HMGB1 and IL-1β are released together. HMGB1 and IL-β have been shown to form complexes in vitro (Sha, Zmijewski et al. 2008, Hreggvidsdottir, Ostberg et al. 2009), but this has not been shown previously in vivo. Given the close connection between HMGB1 and IL-1β secretion, this led us to hypothesize that HMGB1 and IL-1β would form complexes in brain in response to alcohol, since they are often induced coordinately and utilize similar secretion mechanisms. The hippocampus is a critical brain region involved in learning and memory, addiction and other neuropsychiatric illnesses (Luthi and Luscher 2014) as well as a brain region studied for seizures related to HMGB1 and IL-1β regulation of neuronal excitability (Vezzani 2015). Using an acute high dose ethanol exposure we found increases in both HMGB1 and IL-1β in the plasma, brain and lung. Using co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) we found HMGB1 complexed with IL-1β in the brain. Confocal immunofluorescence indicated a transient increase of cytoplasmic HMGB1 colocalized with IL-1β. Using a FLAG-HMGB1 transfection model in hippocampal slice culture, we found that ethanol increased the secretion of FLAG-HMGB1/IL-1β complexes into the culture media. Previous studies have shown HMGB1 increased in post-mortem alcoholic brain (Crews, et.al. Biol. Psych). We report here increased IL-1β in post-mortem human alcoholic hippocampus and increased HMGB1/IL-1β complexes in the hippocampus of human alcoholics by co-IP. HMGB1/IL-1β complexes were potent, causing enhanced responses in brain slice cultures. Thus, ethanol contributes to central immune activation in part through induction HMGB1/IL-1β immune complexes. This identifies a novel functional interaction between the DAMP HMGB1 and the cytokine IL-1β in humans and in vivo that contributes to the immune activation in alcoholism.

Methods

Reagents

The following reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, USA): HMGB1 ELISA kit was purchased from IBL International (Hamburg, Germany). Primary antibodies from Abcam: ChIP grade rabbit anti-HMGB1 (ab18256), goat anti-β actin (ab8229). Primary antibodies from R&D Systems: goat anti-IL-1β for Western Blot (AF-401-NA) and rat anti-IL-1β (MAB401R) for immunofluorescence. Primary antibodies from Cell Signaling: anti-FLAG (14793S). Secondary antibodies for western blot were purchased from Rockland: donkey anti-rabbit DyLight™ 680 (611-744-127) and donkey anti-goat DyLight™ 800 (605-745-125). Secondary antibodies for immunofluorescence were purchased from Molecular Probes: Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit (A-11012); and Biolegend: Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rat (405418). Complete protease inhibitor tablets were purchased from Roche. We prepared synthetic HMGB1/IL-1β heterocomplexes by incubating recombinant HMGB1 (rHMGB1, SIGMA) and recombinant IL-1β (rIL-1β) at 4°C for 24 hours as described previously (Sha, Zmijewski et al. 2008). HMGB1 was 17nM, while two concentrations of IL-1β were assessed, 600pM and 6nM.

Human Postmortem Brain Tissue

Postmortem human hippocampal tissue was obtained from the New South Wales Brain Tissue Bank in Sydney, Australia in accordance with international ethical standards as described previously (Dedova, Harding et al. 2009, Crews, Qin et al. 2013, Coleman, Zou et al. 2017). Both frozen tissue and paraffin embedded hippocampal sections were provided. Those with comorbid liver cirrhosis or nutritional deficiencies were excluded. The leading common cause of death was cardiovascular disease for both groups (16/18). Psychiatric and alcohol use disorder diagnoses were confirmed using the Diagnostic Instrument for Brain Studies, which is in compliance with the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Dedova, Harding et al. 2009). Demographics for each subject are provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Demographics of alcoholic and control subjects from New South Wales Brain Tissue Bank.

Detailed clinical data was collected for each subject as described in Methods. All subjects were male.

| DSM V Alcohol Classification |

Age | PMI | Brain pH | BAC at Death (mg/dL) |

Cause of Death | Agonal State/ Mode of Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 24 | 43 | 6.27 | 0 | Arrhythmia | Rapid |

| Control | 40 | 27 | 6.79 | 0 | Pulmonary Embolus | Intermediate |

| Control | 44 | 50 | 6.6 | 0 | IHD | Rapid |

| Control | 46 | 29 | 6.12 | 0 | MI | Intermediate |

| Control | 48 | 24 | 6.73 | 0 | IHD | Rapid |

| Control | 50 | 30 | 6.37 | 0 | IHD | Rapid |

| Control | 50 | 40 | 6.87 | 0 | Hemopericardium | Rapid |

| Control | 53 | 16 | 6.84 | 0 | Cardiomyopathy | Rapid |

| Control | 60 | 28 | 6.8 | 0 | IHD | Rapid |

| Control | 62 | 46 | 6.95 | 0 | IHD | Rapid |

| Mean ± SEM | 48 ± 3 | 33 ± 3 | 6.56 ± 0.1 | 0 ± 0 | ||

| AUD, Mild | 25 | 43.5 | 6.7 | 193 | CO and EtOH | Intermediate |

| AUD, Moderate | 42 | 41 | 6.5 | 174 | Bromoxynil/EtOH | Intermediate |

| AUD, Remission | 44 | 15 | 6.48 | 0 | IHD | Rapid |

| AUD, Severe | 45 | 18.5 | 6.57 | 297 | Drowning | Intermediate |

| AUD, Severe | 49 | 44 | 6.41 | 30 | IHD | Rapid |

| AUD, Severe | 49 | 16 | 6.19 | 0 | MI | Rapid |

| AUD, Moderate | 50 | 17 | 6.3 | 0 | IHD | Rapid |

| AUD, Severe | 50 | 34.5 | 6.93 | 395 | Acute Bronchitis | Intermediate |

| AUD, Severe | 61 | 59 | 6.57 | 0 | Myocarditis | Intermediate |

| AUD, Severe | 61 | 23.5 | 6.92 | 0 | IHD | Rapid |

| Mean ± SEM | 48 ± 3 | 31 ± 5 | 6.63 ± 0.1 | 108.9 ± 46.4 |

BAC-Blood Alcohol Concentration, AUD-Alcohol Use Disorder, PMI-postmortem interval, IHD-ischemic heart disease, MI-myocardial infarction, CO-Carbon Monoxide.

Agonal state terminal phase durations - rapid: <1hr, intermediate: 1–24hr, long term>24h

Acute Binge Ethanol Treatment and Sacrifice

Male C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks) received one dose of 20% ethanol (w/v) via intragastric administration at a dose of either 1 or 6g/kg. Blood was collected at sacrifice into 4% v/v trisodium citrate anticoagulant, then mice were sacrificed at 6, 12, 18, or 24 hours after ethanol as described previously (Qin, Liu et al. 2013). Briefly, mice received pentobarbital (100mg/kg, i.p.) for anesthesia, and were sacrificed by cardiac perfusion with cold PBS. Brain, liver, and lung tissue were all harvested and frozen on liquid nitrogen. Anticoagulated blood was centrifuged at 3000×g for 10 minutes to remove cells and then stored at −20°C until use.

ELISA measurements of IL-1β

Frozen brains were homogenized in cold lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, 0.25 M sucrose, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100; 100 mg tissue/mL) and 1 tablet of Complete Mini protease inhibitor cocktail tablets/10 ml (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Homogenates were centrifuged at 100,000×g for 40 min, supernatant was collected, and protein levels were determined using the BCA protein assay reagent kit (PIERCE, Milwaukee, WI). The level of IL-1β was measured with the IL-1β commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), as described previously (Gu, Okada et al. 1998). For assessment of total protein bound IL-1β in plasma, plasma samples were diluted 1:25 and then treated with perchloric acid (PCA, BioVision catalog #K808). The supernatant was removed and the IL-1β-containing pellet was resuspended and pH neutralized. The protein concentration was then assessed by BCA and IL-1β measured by ELISA. Total purified IL-1β is presented as ng/mg total resuspended protein.

ELISA measurements of HMGB1

Frozen tissue samples were prepared for ELISA as described above. HMGB1 levels were determined by ELISA (IBL, Germany) as described previously (Coleman, Zou et al. 2017). For tissue samples, equal amounts of total protein (~80µg) were treated with PCA to separate HMGB1 from its binding partners to allow for measurement of total HMGB1 as previously described (Barnay-Verdier, Gaillard et al. 2011, Coleman, Zou et al. 2017). The purified HMGB1-containing supernatant was then assessed by ELISA and reported as ng/mg total protein. Plasma samples were diluted 1:25 in ELISA buffer prior to PCA treatment and analysis by ELISA. Plasma HMGB1 values are presented as ng/mL.

Verification of HMGB1 antibody specificity using HMGB1 knockdown with siRNA in BV2 microglia cell culture

The Invitrogen Silencer™ HMGB1 siRNA was purchased from ThermoScientific. Mouse BV2 microglia underwent RNA interference for HMGB1. BV2 microglia were maintained in culture using techniques routinely performed in our laboratory as described previously (Coleman, Zou et al. 2017, Lawrimore and Crews 2017). Preparation of transfection reagents and transfection were performed according to the manufacturer’s siRNA transfection protocol. Briefly, after 10 minutes of equilibration at room temperature siRNA solution was combined with Lipofectamine 2000 solution to form siRNA liposomes for a further 20 minutes at room temperature. The transfection mixture was added to serum-free N2 medium at a final concentration of 100–500 nM HMGB1 siRNA (Ambion) + 8µl Lipofectamine 2000 in a total volume of 1 ml. Vehicle controls were treated with the same N2 medium containing Lipofectamine only or with negative control siRNA (Sigma). After 48 hours transfection, cells were harvested for Western blot analysis.

Western blot

Organ tissues and cell culture homogenates were homogenized and sonicated in Tris lysis buffer containing 7.4% EDTA, 3.8% EGTA and 1% Triton X-100. Lysates were centrifuged at 21,000×g for 1 hour. Protein rich supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C until use. Samples (30 or 40 µg protein/well) were mixed with DTT containing reducing buffer (Pierce TM catalog number 39000) and RIPA buffer to a final volume of 50µL and boiled for 5 minutes. Samples were run on 4–15% Ready Gel Tris-HCL gel (BioRad), and transferred onto PVDF membranes (BioRad). Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody. Secondary incubation was performed the following day, and membranes visualized and bands quantified using the LiCor Odyssey imaging system™. Values for proteins of interest were normalized to β actin expression for each subject.

Co-immunoprecipitation of HMGB1 and IL-1β complexes

Co-immunoprecipation to assess for HMGB1/IL-1β complexes in mouse brain and liver and hippocampal-entorhinal cortex (HEC) media was performed using the Catch and Release® kit from Millipore according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 500µg of sample was incubated in the spin column with anti-HMGB1 antibody and the included antibody capture affinity ligand for 30 minutes. The flow through was collected by centrifugation of the spin column. The column underwent multiple washes followed by elution. The eluate was assessed by Western Blot for HMGB1 and IL-1β as described previously (Coleman, Zou et al. 2017). IgG controls were run for each tissue type assessed to ensure specific co-immunoprecipitation.

Immunohistochemistry and cell counting

Free floating entorhinal cortex (CTX) sections were processed for immunostaining as previously described (Qin, Wu et al. 2007, Crews, Zou et al. 2011, Qin and Crews 2012, Qin and Crews 2012). Briefly, mice were sacrificed by perfusion with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were extracted and incubated in paraformaldehyde for 24 hours. Brains were sliced into 40µm coronal sections. The sections were washed in PBS and antigen retrieval performed by incubation in Citra solution (BioGenex, San Ramon, CA) for 1hr at 70° C. Following incubation in blocking solution, tissue was processed in primary antibody. The immunolabeling was visualized using nickel-enhanced 3,3’-diaminobenzidinne (DAB) or Alexa Fluor 488 or 555 dye. Negative control for non-specific binding was conducted on separate sections employing the above-mentioned procedures with the exception that the primary antibody was omitted. For the assessment of positive immunoreactivity (+IR), a modified stereology method was used to quantify cells within regions of interest as previously described (Crews, Qin et al. 2013). In each CTX region, +IR was assessed in 4 randomly selected regions of interest per hemisphere, for a total of 8 samples per section. BioQuant Nova Advanced Image Analysis (R&D Biometric, Nashville, TN) was used for image capture and number of +IR cells were counted within the CTX regions.

Immunofluorescent staining and confocal analysis

Immunofluorescent staining for HMGB1 and IL-1β were performed in mouse brain as described above and previously (Coleman, Jarskog et al. 2009). Sections were washed and then permeabilized and blocked in blocking buffer containing 0.2% TX-100 and 3% serum for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were incubated in anti-HMGB1 (1:1000) and anti-IL-1β (1:1000) in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies (1:1000) for 2 hours at room temperature. Secondary-only negative controls were performed without primary antibody incubation. Sections were mounted on slides and coverslipped with anti-fade mounting medium (pro-long; Molecular Probes). Confocal images were obtained using an Olympus FV100 in the UNC Neuroscience Center.

Hippocampal-entorhinal cortex (HEC) slice culture

All protocols followed in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Use Committee at UNC and were in accordance with National Institute of Health regulation for the care and use of animal in research. Organotypic brain slice cultures are prepared as described previously (Zou and Crews 2014). Briefly, the hippocampal entorhinal region is dissected and slice transversely from post-natal day 7 rat pups. Slices are 375µm thick. HEC slices were placed onto tissue insert membrane (10 slices/insert) and cultured with medium containing 75% MEM with 25mM HEPES and Hank’s salts, 25% horse serum (HS), 5.5g/L glucose, 2mM L-glutamine in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 36.5°C for 7 days in vitro (DIV), followed by 4 DIV in medium containing 12.5% HS and then 3 DIV in serum-free medium supplemented with N2. The cultures after 14 DIV were used for experiments and drug treatments with serum-free N2-supplemented medium. For FLAG-HMGB1 transfection, the FLAG-HMGB1 (N-terminal tagged) regular plasmid construct was obtained from VectorBuilder™. HEC slice wells were transfected with the FLAG-HMGB1 plasmid using lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent for 24 hours. Slices were then treated with either saline, LPS (100ng/mL), or ethanol (100mM) for 24 hours.

Isolation of mRNA and quantification by RT-PCR

Isolation of mRNA was performed as previously described (Zou and Crews 2014, Coleman, Zou et al. 2017). Briefly, total RNA was isolated using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc., CA). RNA quantification was performed using a nanodrop 2000™ spectrophotometer. For mRNA reverse transcription, 2µg of RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using random primers (Invitrogen) and reverse transcriptase Moloney murine leukemia virus (Invitrogen). The primer sequences that were used for reverse transcriptase are included in Table 1. Investigated genes of interest were normalized to β actin. Importantly, β actin did not change significantly with ethanol treatments.

Table 1.

Primers used for mRNA quantification by RT-PCR

| Target | Forward (5’ to 3’) | Reverse (5’ to 3’) |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | GAAACAGCAATGGTCGGGAC | AAGACACGGGTTCCATGGTG |

| TNFα | AGCCCTGGTATGAGCCCATGTA | CCGGACTCCGTGATGTCTAAG |

| iNOS | CTCAGCACAG-AGGGCTCAAAG | TGCACCCAAACACCAAGG |

| β-actin | CTACAATGAGCTGCGTGTGGC | CAGGTCCAGACGCAGGATGGC |

Statistical Analyses

Data are expressed as a mean values ± standard error of mean from the indicated number of slices or experiments. Student’s t-tests were performed for orthogonal two-group analyses. For multi-group analyses, or analyses across time a one-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test was utilized. Differences were considered to be statistically significant if p value of <0.05.

Results

HMGB1/IL-1β complexes cause enhanced immune gene induction in hippocampal-entorhinal cortex (HEC) brain slice culture

Recombinant HMGB1 and IL-1β have previously been shown to form complexes in vitro that cause enhanced immune responses in peripheral macrophage and mammary cell lines (Sha, Zmijewski et al. 2008, Hreggvidsdottir, Ostberg et al. 2009). Therefore, we hypothesized that HMGB1/IL-1β complexes would also cause enhanced neuroimmune responses. Thus, we investigated whether these complexes enhanced neuroimmune activation using rat hippocampal slice culture. We prepared synthetic HMGB1/IL-1β heterocomplexes by incubating recombinant HMGB1 (rHMGB1) and recombinant IL-1β (rIL-1β) at 4°C for 24 hours as described previously (Sha, Zmijewski et al. 2008). HMGB1 was 17nM, while two concentrations of IL-1β were assessed, 600pM and 6nM. Co-immunoprecipitation for HMGB1 indicated IL-1β was pulled down consistent with HMGB1/IL-1β complex formation (Figure 1A). Treatment of HEC brain slice cultures with HMGB1/IL-1β complexes increased iNOS and IL-1β mRNA (Figure 1B, C). HMGB1 alone (17nM) had no effect on iNOS or IL-1β mRNA expression in HEC. IL-1β alone (600pM-6nM) caused a dose-dependent increase in iNOS mRNA by 712% and 2981% at 600pM and 6nM respectively (Figure 1B). IL-1β induced its own mRNA to 2367% and 11,621% of control at 600pM and 6nM respectively (Figure 1C). Interestingly, HMGB1/IL-1β complexes formed using the same concentrations as HMGB1 and IL-1β alone, caused an enhancement of the induction iNOS and IL-1β mRNA. HMGB1/IL-1β complexes increased iNOS induction by approximately 2-fold above IL-1β alone (Figure 1B, 1452% and 4941% above control at 600pM and 6nM IL-1β). Similarly, HMGB1/IL-1β complexes increased IL-1β gene induction by 1.7 to 3.5 fold above IL-1β alone (8379% and 19,916% above control at 600pM and 6nM IL-1β respectively). The lack of an effect of HMGB1 alone at this concentration suggests the enhanced activity of the heterocomplex is through the IL-1β receptor rather than through HMGB1 acting on another receptor (e.g. TLR4 or RAGE). We investigated the IL-1β receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) on HMGB1/IL-1β heterocomplex activation and found IL-1RA reduced the HMGB1/IL-1β induction of TNFα and IL-1β mRNA to control levels and iNOS mRNA by 64% (Figure 1D). Thus, the HMGB1/IL-1β heterocomplexes can induce neuroimmune mRNA in HEC brain slice cultures.

Figure 1. HMGB1/IL-1β complexes have enhanced pro-inflammatory action through IL-1β signaling.

Recombinant HMGB1 (rHMGB1) and recombinant IL-1β (rIL-1β) were at 4C for 24 hours to form HMGB1/IL-1β complexes. Hippocampal entorhinal brain slice culture (HEC) were incubated with HMGB1 (17nM) alone, IL-1β alone (600pm or 6nM), HMGB1/IL-1β (17nM/600pM or 17nM/6nM) for 24 hours. Innate immune gene induction was assessed by RT-PCR. (A) Co-immunoprecipitation was performed of synthetic HMGB1/IL-1β complexes to assess for stable complex formation. The entire western blot of eluate confirmed complex formation is shown. Eluate was probed for either anti-IL-1β (800 channel, red) or anti-HMGB1 (700 channel, green) antibodies. Bands consistent with the eluted HMGB1 and IL-1β were seen consistent with successful synthetic complex formation. (B) iNOS gene induction by HMGB1/IL-1β complexes. HMGB1 alone did not induce iNOS. IL-1β alone (600pM and 6nM) increased iNOS by 712% and 2981% respectively (Figure 5B). HMGB1/IL-1β complexes increased iNOS expression by 1.7- 2-fold above IL-1β alone (1452% and 4941% at 600pM and 6nM). (C) IL-1β induced its own gene induction to 2367% and 11,621% of control (600pM and 6nM respectively). HMGB1/IL-1β complexes increased IL-1β gene induction by 1.7 to 3.5 fold above IL-1β alone (8379% and 19,916% above control, 600pM and 6nM IL-1β respectively). (D) IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1 RA) reduced the HMGB1/ILβ induction of iNOS by 64% while returning TNFα and IL-1β to control levels. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, N=3 per group.

Induction of Brain and Plasma IL-1β and HMGB1 by Acute Binge Ethanol Exposure

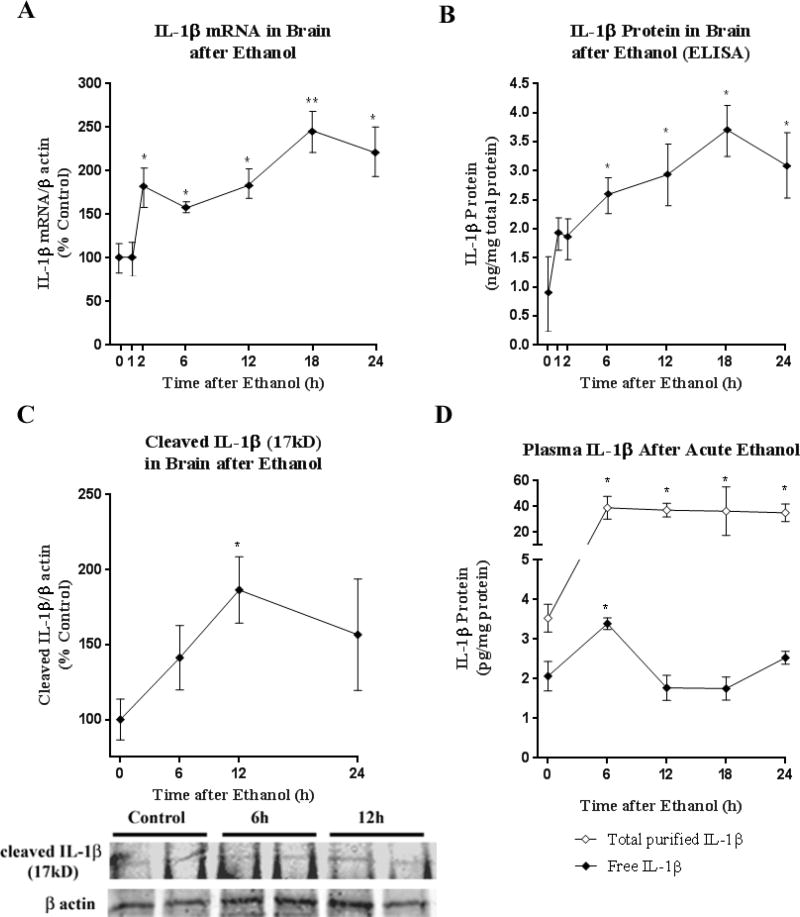

To determine the effects of ethanol in vivo on IL-1β and HMGB1 we studied an acute intragastric binge ethanol exposure model in mice (6g/kg, i.g.) that produced very high BACs (~400mg/dL peak at 1 hour), similar to that found during black outs (White and Hingson 2013) and in heavy drinking alcoholics (Table 2) (Adachi, Mizoi et al. 1991). Mice showed transient sedation to mild anesthesia with zero mortality and no physical signs of withdrawal as described previously in studies finding acute ethanol withdrawal induces neuroimmune gene expression in whole brain (Walter and Crews 2017). Acute ethanol exposure increases both IL-1β mRNA gene transcription and protein, e.g. translation (Figure 2A–B) in whole brain. IL-1β mRNA was increased within 2h post-ethanol and sustained up to 24 hours, reaching a peak of ~2.5-fold control levels at 18 hours (Figure 2A). IL-1β protein, measured by ELISA in whole brain, was induced, peaking at 3.5-fold over control at 18 hours post-ethanol (Figure 2B). In order to ensure this represented active, cleaved IL-1β, western blot was performed. Western blot confirmed a transient increase in the active cleaved IL-1β isoform in whole brain, which peaked at 1.9-fold of control levels at 12 hours (Figure 2C). Thus, in mice acute ethanol increases whole brain IL-1β mRNA and protein.

Figure 2. Acute Binge Ethanol Model induces IL-1β mRNA and Protein in Brain and Plasma.

Mice were treated with acute binge ethanol (6g/kg, i.g). (A) IL-1β mRNA was assessed by RT-PCR in whole brain. By 2h post-ethanol, IL-1β mRNA was increased and sustained up to 24 hours, reaching a peak of ~2.5-fold control levels at 18 hours. (B) IL -1β was measured by ELISA in control and ethanol-treated mice. Ethanol caused induction of IL-1β protein, peaking at 3.5-fold control leves at 18 hours post-ethanol. (C) Active, cleaved IL-1β (17kD) was measured in whole brain by western blot. Cleaved IL-1β reached 1.9-fold control levels at 12 hours (186.4 ± 22.13 vs 100.0 ± 13.66, Ethanol vs. Control ± SEM, *p<0.05, t-test. (D) Free and complexed IL-1β protein levels were measured in plasma after ethanol by ELISA. Ethanol caused a transient increase in free IL-1β levels, which peaked at 6 hours after ethanol (70% increase, 31.8±2.4 vs. 18.71±2.4 pg/mg, Ethanol vs. Control, p<0.0004, N=9). Assessment of complexed IL-1β. Total plasma IL-1β purified from binding partners was increased up to 24 hours post-ethanol, up to nearly 10-fold greater than controls. N=9–10 per group **p<0.01, *p<0.05, t-test vs control.

IL-1β has been shown previously to be increased in the blood of human alcoholics and may serve as a biomarker for disease progression (Leclercq, De Saeger et al. 2014). We hypothesized that HMGB1-IL-1β heterodimers might not be included with measured IL-1β protein in the plasma by ELISA. IL-1β is known to bind other plasma proteins as well (Borth and Luger 1989). In order to determine if conventional ELISA might underestimate IL-1β levels by not measuring HMGB1 and other protein-bound forms of IL-1β, we also measured IL-1β in plasma after acid separation and purification from HMGB1. HMGB1 is soluble in perchloric acid, while IL-1β separates from HMGB1 in a precipitate (Barnay-Verdier, Gaillard et al. 2011). IL-1β-containing precipitate was resuspended and then assessed by ELISA. Free, non-protein bound IL-1β was increased transiently in the plasma by 70% increase at 6 hours after ethanol, returning to baseline levels (Figure 2D, *p<0.05). Acid purification showed increases in IL-1β after ethanol up to 10-fold in magnitude greater than non-purified plasma, which remained elevated up to 24 hours after ethanol. At t=0 controls, however, the IL-1β protein was similar in both measurement groups (2–3.5pg/mg), suggesting that ethanol treatment increases IL-1β binding to acid soluble proteins, of which HMGB1 is prevalent. This suggests that conventional measurements of IL-1β do not measure the majority of plasma IL-1β such as HMGB1/IL-1β heterocomplexes. Since HMGB1/IL-1β heterocomplexes are far more potent than IL-1β alone, traditional measures might not detect an important signaling complex.

We have recently reported that HMGB1 is increased in the hippocampus of human alcoholics (Coleman, Zou et al. 2017). Chronic alcohol induces HMGB1 in the brain in vivo (Crews, Qin et al. 2013, Lippai, Bala et al. 2013). We now assessed whether acute binge ethanol causes similar HMGB1 induction. Consistent with previous observations (Lippai, Bala et al. 2013, Bala, Marcos et al. 2014), blood endotoxin was increased by ethanol, and closely followed the blood alcohol levels, peaking at 1 hour and returned to near baseline levels by 18 hrs (not shown). In whole brain, ethanol caused a rapid increase in HMGB1, reaching 171% of control levels by 1 hour (Figure 3A, p<0.02). HMGB1 remained elevated for several hours, but returned to control levels by 48 hours after ethanol. Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of HMGB1 in CTX showed good visualization with neuronal nuclear HMGB1+immunoreactivity (+IR) clearly seen. Cortical HMGB1+IR was increased by 1.7-fold of control by ethanol and remained elevated at 24 hours post-ethanol (Figure 3B). Representative images show increased HMGB1+IR after ethanol (Figure 3C). In blood, ethanol caused a transient increase in plasma HMGB1 (Figure 3C, F(6,29)=0.7107, p<0.0003). Plasma HMGB1 levels peaked to approximately 229% of control levels at 12 hours after ethanol administration (***p<0.0001). Low-dose ethanol (1mg/kg) had no effect on plasma HMGB1 or endotoxin (not shown). Thus, acute binge ethanol exposure, but not low moderate ethanol exposure of mice, results in a rapid and prolonged increase in HMGB1.

Figure 3. Acute Binge Ethanol induces HMGB1 Levels in Brain and Plasma.

Mice were treated with ethanol (6g/kg, i.g). HMGB1 protein levels were measured at different time points by ELISA and Immunohistochemistry (IHC). (A) Whole brain HMGB1 increased within 1 hour (173% increase, p<0.05) and stabilized to control levels by 48h (F(6,31)=1.290, p<0.03) (B) Quantification of IHC of HMGB1 showed increased cortical HMGB1 after binge ethanol. HMGB1+immunoreactive (IR) cells were increased by 1.7-fold up to 24 hours after ethanol treatment. (C) Representative images of HMGB1 IHC in mouse cortex after ethanol showing increased numbers of HMGB1+IR cells. (D) Binge-ethanol (6g/kg) caused a transient increase in plasma HMGB1 (F(6,29)=0.7107, p<0.0003). HMGB1 levels peaked at 12 hours after ethanol (226% increase, p<0.001). N=4–11 mice per time point, 1-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

HMGB1 is complexed with IL-1β in brain

HMGB1 and IL-1β have been shown to form complexes in vitro that possess enhanced IL-1R potency (Sha, Zmijewski et al. 2008, Hreggvidsdottir, Ostberg et al. 2009) similar to our findings reported here in brain slice cultures. To determine if complexes were formed in brain we performed western blot for HMGB1. HMGB1+ bands were found at multiple different molecular weights. The expected ~29kD band was observed (Figure 4A, left panel), however, additional higher molecular weight bands were also observed at 37–50kD, 50–65kD, and 150kD. Separate blots were probed after primary antibody was pre-incubated with the HMGB1 immunogenic peptide prior to incubation. Pre-absorption with the primary antibody caused the disappearance of four of these bands, suggesting specific antigen recognition by the primary antibody, rather than non-specific secondary antibody staining (Figure 4A, right panel). We observed a similar pattern of staining using an antibody from a different company that has been verified using RNA interference (GeneTex, not shown). However, in order to confirm that the higher molecular weight bands in our setting represent specific binding to HMGB1, we performed validation of the HMGB1 antibody using siRNA. Utilizing a mouse microglia cell line (BV2) we incubated with siRNA to HMGB1 at different concentrations. Lysates from control cell lysates showed a similar pattern of HMGB1+ bands as the mouse brain tissue (Figure 4B). Incubation with siRNA to HMGB1 resulted in a concentration-dependent depletion of all HMGB1+ bands, both the free 29KD and the higher molecular weight bands. This confirmed that the higher molecular weight bands do indeed contain HMGB1. We hypothesized that some of the higher molecular weight bands might represent HMGB1 complexes. HMGB1 is known to form stable complexes with IL-1β in vitro (Sha, Zmijewski et al. 2008, Hreggvidsdottir, Ostberg et al. 2009). Thus, we hypothesized that some of the HMGB1+ bands might represent HMGB1/IL-1β complexes. Probing of blots with HMGB1 and IL-1β revealed an ~65kD band that was positive for both HMGB1 and IL-1β (Figure 4C). As expected a lower 30kD band consistent with pro-IL-1β was also observed (not shown). The higher molecular weight IL-1β positive band disappeared upon pre-incubation of the primary antibody with the IL-1β immunogenic peptide suggesting specific antibody recognition (Figure 4D, lower). This is consistent with previous findings that show higher molecular weight IL-1β complexes in human samples (Belov, Meher-Homji et al. 1999). This led us to perform co-immunoprecipitation for HMGB1 and IL-1β to determine if these form complexes are present as shown in Figure 4E. HMGB1 was successfully immunoprecipitated from brain tissue, as the flow through showed no HMGB1 (Supplemental Figure 1B), while clear HMGB1+ bands were seen in the eluate (Figure 4E, lower, Supplemental Figure 1A). Western blot of the eluate probed for IL-1β found that both cleaved IL-1β (17kD) and pro-IL-1β were in the eluate from both controls and ethanol treated groups, identifying HMGB1 and IL-1β complexes in the mouse brain (Figure 4E, upper, Supplemental Figure 1A). Thus, HMGB1-IL-1β complexes appear to be present in brain as well as other possible HMGB1 complexes. Since HMGB1 is known to bind multiple cytokines (Sha, Zmijewski et al. 2008), the presence of other possible HMGB1/cytokine combinations should be investigated in vivo.

Figure 4. HMGB1 and IL-1β form heterocomplexes together in mouse brain.

Mice were treated with either water or ethanol (6g/kg, i.g). Brain protein was isolated and western blot performed. (A) Multiple bands stained positive for HMGB1. On a separate blot of the same samples, HMGB1 antigenic peptide (10µg/mL) was pre-incubated with HMGB1 antibody prior to overnight incubation with the blot to identify specific HMGB1 bands. Arrows show bands with specific HMGB1 staining that disappear after pre-incubation of primary antibody with HMGB1 immunogenic peptide. Western blots shown in A are not for quantitation, but to show that preincubation with exogenous HMGB1 reduces heterocomplex detection (B) HMGB1 antibody validation by western blot of mouse-derived BV2 microglia cell lysates with siRNA for HMGB1. Mouse BV2 microglia were incubated with siRNA (100–500nM) as described in Methods. Similar to mouse brain, multiple HMGB1+ bands were observed both at 29kD and at higher molecular weights (arrowheads). With increasing concentrations of siRNA to HMGB1, each of these bands disappeared though GAPDH remained similar, indicating specific antibody staining at both 29kD and higher molecular weights. (C) Fluorescent Western Blot of brain protein stained for both HMGB1 and IL-1β. Composite overlay shows a ~65kD band was positive for both HMGB1 and IL-1β (C) Western blot for IL-1β showing an IL-1β+ band at ~65kD. Pre-incubation of the IL-1β peptide with the immunogenic peptide caused disappearance of the ~65kD band indicating antigen specificity (D) Schematic of co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assessment for HMGB1/IL-1β complex formation. Agar beads coupled with anti-HMGB1 antibodies to precipitate for HMGB1. Elution of HMGB1 from anti-HMGB1 complexes allowed for detection of HMGB1/IL-1β complexes by western blot. (E) Immunoprecipitation for HMGB1 was performed. Western blots on the eluate for IL-1β and HMGB1 found both IL-1β and HMGB1 in the eluate consistent with the presence of HMGB1-IL-1β heterocomplexes in mouse brain.

Although HMGB1-IL-1β complexes were found in brain, they were not found in liver. HMGB1 is also increased in alcoholic liver disease (Ge, Antoine et al. 2014). Acute binge ethanol exposure caused a transient increase in HMGB1 as measured by ELISA peaking 12 hours after ethanol treatment reaching 140% of control levels (Supplementary Figure 2A). HMGB1 was assessed by Western Blot analysis to investigate for higher molecular weight HMGB1 complexes. However, there was not a higher molecular weight ~65kD HMGB1+ band in liver tissue suggesting HMGB1-IL-1β complexes are not formed in liver as in the brain (Supplementary Figure 2B). Co-immunoprecipitation was performed to assess for HMGB1/IL-1β complex formation. As with the brain tissue, the immunoprecipitation of HMGB1 was efficient as HMGB1 was found in the eluate (Supplementary Figure 2C, top), but with no HMGB1 found in the flow through (Supplemental Figure 2D). Consistent with the absence of a ~65kD HMGB1/IL-1β+ band in the Western blot of liver protein, no IL-1β was detected in the Co-IP eluate (Supplementary Figure 2C, bottom). Importantly, IL-1β+ bands were found in the flow through, indicating the presence of IL-1β, though HMGB1/IL-1β complexes were not detected (Supplemental Figure 2D). Thus, though HMGB1 is induced by ethanol in both brain and liver, but HMGB1/IL-1β complexes appear to be formed in brain, but not liver.

HMGB1 and IL-1β are both released from cells by an unconventional vesicular secretion mechanism that requires caspase-1 (Gardella, Andrei et al. 2002, Lamkanfi, Sarkar et al. 2010, Dupont, Jiang et al. 2011). Therefore, we hypothesized that HMGB1 and IL-1β might associate in the cytoplasm for co-release. We used immunofluorescence to identify HMGB1 and IL-1β in the mouse brain. Confocal microscopy with DAPI to label nuclei, found that HMGB1 and IL-1β were co-localization in the cytoplasm (Figure 5A, C, and D). Analysis of representative colabeled punctate sites confirmed co-localization with Pearson’s correlation coefficients being mostly between 0.7–0.8 (Figure 5B). Acute ethanol treatment increased the co-localization of HMGB1 and IL-1β. Images from multiple samples are shown in Figure 5C. A higher magnification image from an ethanol-treated subject at 12 hours is shown to more easily visualize the colabeling (Figure 5D). Quantification of colabeled puncta showed that at 12 hours post-ethanol, robust cytoplasmic co-localization of HMGB1 and IL-1β was observed (Figure 5E). This time period between 12–24 hours corresponded with the peak in IL-1β expression determined by ELISA and western blot (Figure 2B). By 24 hours, HMGB1/IL-1β co-localization returned to control levels (Figure 5E). Quantification of HMGB1+/IL-1β+ colocalized puncta found nearly a 2-fold increase at 12 hours after ethanol (Figure 5E, p<0.05). Secondary antibody alone negative controls showed diffuse background staining (Supplemental Figure 3). Thus, HMGB1/IL-1β co-localization in cell cytoplasm structures in brain was induced transiently by ethanol.

Figure 5. Ethanol transiently increases HMGB1 and IL-1β cytoplasmic co-localization.

HMGB1 and IL-1β immunofluorescence were visualized in mouse cortex by confocal microscopy (90×) in control and ethanol (6g/kg, i.g.) treated mice (A) HMGB1 and IL-1β co-localized to a degree in the cytoplasm of controls and ethanol treated mice. DAPI colabeling of nuclei shows that colocalization occurred in the cell cytoplasm. Arrows denote sites of visible colocalization (B) Analysis of sites of visible colocalization was assessed for accuracy using Pearson’s method. Pearson’s correlation values for representative sites of visible colocalization were determine and were mostly between 0.7–0.8 indicating colocalization. (C) Representative images of individual subjects. White arrows denote sites of colocalization. Ethanol treatment caused a robust increase in cytoplasmic HMGB1 and IL-1β co-localization 12 hours after treatment. At 24 hours post-ethanol treatment, cytoplasmic HMGB1 and IL-1β co-localization was observed to a lesser degree (D) High magnification from a 12 hour ethanol treated subject (number 2, boxed region) showing punctate sites of colocalization. HMGB1 (green) is primarily nuclear. Yellow puntate cytoplasmic colocalization sites are highlighted by arrowheads. (E) Quantification of HMGB1+/IL-1+ colocalized staining showed a near 2-fold increase in HMGB1/IL-1β co-localization in mouse cortex at 12 hours; 1-way ANOVA F(2,6)=13.2, p<0.0064; Sidak’s post-test 57 vs 33.3, Ethanol 12h vs. control, *p<0.05, N=3 subjects per group. Inserts show high magnification images of selected regions. Arrowheads denote HMGB1/IL-1+ colocalization.

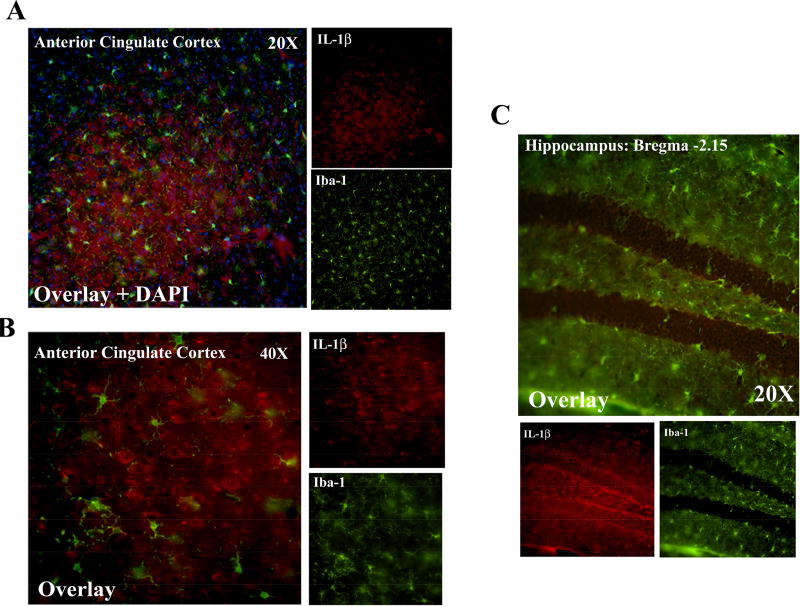

IL-1β colocalizes with neurons in adult mouse brain

In order to gain insight into the cell type involved in the induction of HMGB1/IL-1β we performed immunofluorescent co-labeling for IL-1β and cell type-specific markers for neurons (NeuN) and microglia (Iba-1). Surprisingly, we found that IL-1β was highly localized in the cytoplasm of NeuN+ cells in the motor cortex (Figure 6A), anterior cingulate cortex (Figure 6B), and the hilus of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus (Figure 6C–D). We did not find co-localization of IL-1β with Iba-1+ microglia in the anterior cingulate cortex (Figure 7A–B) or in the hippocampus (Figure 7C). Ethanol treatment did not cause any additional induction of IL-1β in Iba-1+ microglia (not shown). Thus, neurons clearly express IL-1β and appear to be sites of HMGB1/IL-1β colocalization that we observe.

Figure 6. IL-1β co-localizes with neurons in adult mouse brain.

Co-immunofluorescence was performed for the neuronal marker NeuN and IL-1β in adult mouse motor cortex, cingulate cortex and dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. (A) IL-1β+ and NeuN+ cells showed a high degree of colocalization in the motor cortex. NeuN staining was nuclear, while IL-1β filled the cytoplasm. (B) IL-1β+ and NeuN+ cells showed a high degree of colocalization in the anterior cingulate cortex. NeuN staining was nuclear, while IL-1β filled the cytoplasm. (C) IL-1β+ and NeuN+ cells showed a high degree of colocalization in the hilus of the hippocampus but not the granular cell layer (bregma-2.15mm). (D) IL-1β+ and NeuN+ cells showed a high degree of colocalization in more posterior hilar regions of the hippocampus but not the granular cell layer (bregma-2.53mm).

Figure 7. IL-1β shows minimal colocalization with Iba-1 positive microglia in adult mouse brain.

Co-immunofluorescence was performed for the microglia marker Iba-1 and IL-1β in adult mouse cingulate cortex and dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. (A) 20× magnification with Dapi costain shows DAPI nuclear staining with surrounding cytoplasmic IL-1β staining. IL-1β and Iba1 were not seen to colocalize at this magnification (20×) (B) Higher magnification assessment of the cingualate cortex did not find colocalization of Iba-1 and IL-1β+ in the anterior cingulate cortex. (C) IL-1β+ and Iba1 did not significant colocalization in the hilus of the hippocampus but not the granular cell layer (bregma-2.15mm).

Ethanol induces secretion of FLAG-HMGB1/IL-1β complexes from hippocampal-entorhinal (HEC) slice culture

We next asked whether HMGB1/IL-1β complexes could be secreted from brain tissue. Therefore, we used the ex-vivo rat hippocampal-entorhinal slice culture (HEC). We developed a FLAG-HMGB1 plasmid construct, allowing the use of the FLAG tag for immunoprecipitation from media. HEC brain slice cultures were transfected with FLAG-HMGB1 plasmid for determination of released HMGB1/IL-1β complexes into the media. Some slices were treated with either ethanol (100mM) or LPS (100 ng/mL, as a positive control) for 24 hours. After treatment, immunoprecipitation of the media was performed for FLAG, and western blot of eluate for FLAG and IL-1β. Cleaved IL-1β was found in the eluate, consistent with release of HMGB1/IL-1β heterocomplexes (Figure 8A, upper, Supplemental Figure 4). A very dark pro-IL-1β band was also seen in the eluate (Supplemental Figure 4), indicating that HMGB1 and pro-IL-1β associate, as seen in the mouse tissue. However, some pro-IL-1β also elutes from HEC slice media when an IgG control is used rather than the anti-HMGB1 antibody (Supplemental Figure 6), suggesting some of the pro-IL-1β in the eluate may be due to non-specific interactions. FLAG-HMGB1 was also identified in eluate following co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) as expected (Figure 8A, lower, Supplemental Figure 4). Both LPS and ethanol increased media IL-1β in the eluate. Quantification found a 46% and 43% increase IL-1β(OD)/FLAG-HMGB1(OD) in eluate after LPS and ethanol treatment respectively (Figure 8B, *p<0.05). Thus, ethanol increases the release of HMGB1/IL-1β complexes from ex vivo brain slice culture. As shown in Figure 1, these complexes have enhanced neuroimmune potency, with ethanol causeing the secretion of these potent complexes from hippocampal slice tissue. Thus, in response to ethanol HMGB1/IL-1β complexes form in brain and are released into the media. These complexes may have potent autocrine or paracrine immune signaling activity (Figure 8C).

Figure 8. Increased Release of HMGB1/IL-1β Complexes from Hippocampal Slice Culture (HEC) in Response to Ethanol.

Rat hippocampal-entorhinal slice culture (HEC) sections were transfected with either control or a FLAG-HMGB1 plasmid as described in the Methods. Sections were then treated with either saline, LPS (100ng/mL) or Ethanol (100mM) for 24 hours. Slice culture media was collected and co-immunoprecipitation was performed for FLAG-HMGB1 and IL-1β to assess the release of FLAG-HMGB1/IL-1β heterocomplexes. (A) Western blot was performed on the eluate and probed with either anti-FLAG or anti-IL-1β antibodies. FLAG-HMGB1 was detected in the eluate at the molecular weight expected, ~25–29kD. Cleaved, active IL-1β was also detected in eluate consistent with HMGB1/IL-1β complex detection. (B) Quantitation of OD of IL-1β and FLAG-HMGB1 found that LPS and ethanol increased the secretion of IL-1β with FLAG-HMGB1 146% and 143% respectively relative to control, *p<0.05, t-test, N=2 culture wells per group. (C) Schematic illustrating ethanol-induced secretion of HMGB1/IL-1β complexes and their resulting enhance immune activation.

IL-1β, HMGB1, and HMGB1/IL heterocomplexes are Increased in Postmortem Human Alcoholic Hippocampus

To determine if these findings are representative of human brain we investigated post-mortem human alcoholic hippocampus. We have previously found increased HMGB1 and Toll-like receptor expression in cortex and hippocampus (Crews, Qin et al. 2013, Coleman, Zou et al. 2017). Hippocampal IL-1β is linked to HMGB1 release and hippocampal seizures (Maroso, Balosso et al. 2011), is increased by alcohol in mouse cerebellum (Lippai, Bala et al. 2013) and amygdala where it is linked to alcohol self-administration (Marshall, Casachahua et al. 2016). We previously found increased IL-1β in the human hippocampus using immunohistochemistry (Zou and Crews 2012). Prior to assessing for HMGB1/IL-1β complexes in the human hippocampus, we first attempted to replicate the finding of increased IL-1β in this different patient population using ELISA. Age-matched healthy control and human alcoholic samples showed no significant differences in post-mortem interval (PMI), or other factors (see Table 2). IL-1β was significantly increased in the hippocampus of alcoholics by 42% (Figure 9A, p<0.05). Interestingly, IL-1β level was positively correlated with BAC at death (R=0.5, *p<0.05, not shown). We recently found that HMGB1 was increased in the postmortem hippocampus of human alcoholics (Figure 9B). Human alcoholics showed a 24% increase in hippocampal HMGB1 protein (157.8 ±24.7 vs 195.5± 60.1 ng/mg Protein, Control vs Ethanol, *p<0.05). Since ELISA values found HMGB1 and IL-1β increased in the postmortem hippocampus from human alcoholics, we performed co-immunoprecipitation for HMGB1 and IL-1β from postmortem human alcoholic hippocampus. Alcoholic individuals that had a positive BAC at death were assessed, since IL-1β protein correlated with BAC at death. Immunoprecipitation for HMGB1 followed by western blot of the eluate found both HMGB1+, pro-IL-1β and cleaved IL-1β+ bands (Figure 9C, Supplemental Figure 5). The cleaved 17kD IL-1β bands were light compared to the pro-IL-1β bands, but were quantifiable. Future studies should investigate the role of HMGB1/pro-IL-1β complexes. The optical densitometry (OD) of these bands was quantified, and the ratio of IL-1β(OD)/HMGB1(OD) was increased in the human alcoholic brains by 2.8-fold (Figure 9C, p<0.05). This is the first observation to our knowledge of the detection of HMGB1/IL-1β complexes either in humans or in vivo. Since these HMGB1/IL-1β complexes have enhanced immune activating potential they may contribute to brain neuroimmune signaling.

Figure 9. Increased IL-1β, HMGB1 and HMGB1/IL-1β complexes in the hippocampus of human alcoholics.

Postmortem human hippocampal brain tissue was obtained from the New South Wales Tissue Bank. Protein was isolated from frozen tissue and assessed for IL-1β and HMGB1 protein level by ELISA. (A) Human alcoholics showed a 42% increase in IL-1β above healthy controls: 404.5 ± 51.5 vs 573.4 ± 99.2pg/mg, Control vs Ethanol, *p<0.05, paired two-tailed t-test, N=10 per group. (B) Human alcoholics showed a 24% increase in HMGB1 (157.8 ±24.7 vs 195.5± 60.1 ng/mg, Control vs Ethanol, *p<0.05, paired two-tailed t-test, N=10 per group. Note: Data published previously from this same cohort of patients in a different form in Coleman et al J Neuroinflammation 2017. (C) Co-Immunoprecipitation for HMGB1 and IL-1β was performed on postmortem human hippocampus from healthy controls and alcoholics. Eluate was probed for either HMGB1 or IL-1β. HMGB1+ bands were observed at the expected 25–29kD MW. An IL-1β+ band was also observed at ~17kD consistent with cleaved IL-1β, indicating the presence of HMGB1-IL-1β complexes. Quantification of optical densitometry of each band found an increased ratio of IL-1β to HMGB1 in eluate consistent with increased HMGB1-IL-1β complex formation in the hippocampus of human alcoholics. Alcoholics showed a 275% increase in IL-1β association with HMGB1 relative to control. *p<0.05, paired t-test, N=4 per group (D) Theoretical model of enhanced HMGB1/IL-1β signaling

Discussion

The induction of neuroimmune responses has been implicated in an array of psychiatric disorders, including addiction (Crews, Lawrimore et al. 2017), depression (Hodes, Kana et al. 2015, Bhattacharya, Derecki et al. 2016) and autism spectrum disorders (McCarthy and Wright 2017). Neuroimmune activation is key feature of alcoholism and may underlie much of the pathology, with aberrant immune activation being implicated in each of the stages of addiction (for review see Crews et al Neuropharmacology 2017). HMGB1 in particular is a key player in these pathologies. Previous studies have shown that human alcoholics have induction of Toll-like receptor signaling and expression of the endogenous TLR4 ligand, HMGB1 (Crews, Qin et al. 2013). We report here increased IL-1β, HMGB1 and HMGB1/IL-1β complexes in postmortem human alcoholic brain. Previous studies have also found that chronic alcohol induces HMGB1 in the brain in vivo (Crews, Qin et al. 2013, Lippai, Bala et al. 2013). We now show that a single acute administration of binge ethanol causes similar HMGB1 induction. HMGB1 and IL-1β were found in immunogenic complexes in mouse, rat brain slice cultures and human post-mortem alcoholics. HMGB1/IL-1β complexes are secreted into the media from rat hippocampal slice culture in response to ethanol or LPS, and caused enhanced induction of proinflammatory cytokines TNFα and IL-1β as well as iNOS. We find it interesting that though these complexes were found in brain tissue, they were not present in liver. It is not clear why this does not occur in the liver, but does suggest there may be organ specificity. We do find the presence of HMGB1/IL-1β in plasma (unpublished observations). Future studies should investigate whether HMGB1/IL-1β complexes are in other organs and if they modulate immune responses. Therapies that target HMGB1/IL-1β complexes (e.g complex-recognizing antibodies) or prevent their secretion could offer a unique benefit in pathologies involving neuroimmune activation such as alcoholism.

HMGB1 and IL-1β have previously been shown to form immunogenic complexes when incubated in vitro using (17nM HMGB1, 600pM IL-1β) (Sha, Zmijewski et al. 2008, Hreggvidsdottir, Ostberg et al. 2009). We replicate those findings here in brain slice culture and findfind a role for this complex formation in human brain and in vivo. Various sources of HMGB1 have different activity due to oxidative and other post-translational differences, our studies used 17 nM HMGB1, which was not active alone after 24 hour treatment, but enhanced IL1β responses. HMGB1 has multiple post-translational modifications including acetylation, phosphorylation and oxidation (Sahu, Debnath et al. 2008, Liu, Fang et al. 2012, Yang, Lundback et al. 2012, Janko, Filipovic et al. 2014). It is not clear which post-translational forms of HMGB1 are in heterocomplexes, however, we have previously found that ethanol and inhibition of HDAC increases HMGB1 acetylation and secretion from brain slice cultures (Zou and Crews PLOS One 2014) consistent with acetylated HMGB1 being released. Additional studies are needed to know which form of HMGB1 are in heterocomplexes. This is an ongoing investigation and will be a focus of future studies. Both HMGB1 and IL-1β are capable of utilizing unconventional secretion mechanisms, since they lack a leader sequence to target them to conventional secretion pathways. This involves release in secretory lysosomes or autophagasomes (Andrei, Dazzi et al. 1999, Dupont, Jiang et al. 2011) or shedding from the cell membranes (MacKenzie, Wilson et al. 2001, Pelegrin, Barroso-Gutierrez et al. 2008, Chen, Li et al. 2016). HMGB1 and IL-1β can certainly be released independently, but our data find that these proteins associate in the cytoplasm in response to ethanol and may be secreted together. This could be due to association in secretory vesicles, but this needs to be elucidated further. The mechanisms of HMGB1/IL-1β heterocomplex release is likely unconventional, since neither of these proteins have leader sequences targeting vesicles and can be secreted in vesicles (Andrei, Dazzi et al. 1999, Dupont, Jiang et al. 2011). Future studies, however, are needed to determine the precise mechanism of secretion. Our data suggests complexes are primarily in neurons, a surprising finding since microglia are the main immune cell in brain. Previous studies find that removal of brain microglia does not change brain IL1β mRNA in mice (Walter and Crews 2017), and IL1β as well as inflammasomes, the IL1β synthetic machinery are formed in neurons of brain slice cultures (Zou and Crews 2012). However, expression of IL1β and HMGB1 occurs in microglia so complexes in these cells or in astrocytes would be difficult to rule out. The potential of a common pathway of secretion that leads to enhanced immune signaling could represent an optimal target for therapeutic intervention. IL-1β in human hippocampus correlated with blood alcohol concentration at death rather than lifetime consumption of alcohol, and acute binge ethanol transiently increased IL-1β in mouse brain. This suggests that the acute intake of alcohol is directly linked to IL-1β expression in human alcoholics. HMGB1 seems to be more of a chronic immune mediator in alcoholism, as hippocampal HMGB1 protein correlates with lifetime ethanol consumption (Coleman, Zou et al. 2017) and HMGB1 remains persistently elevated into abstinence in several alcohol treatment paradigms (Vetreno and Crews 2012, Crews, Qin et al. 2013, Montesinos, Pascual et al. 2015). HMGB1 is thought to “prime” neuroimmune responses to IL-1β through TLR4 induction of inflammasome assembly (Hornung and Latz 2010, Frank, Weber et al. 2016). Further, nuclear HMGB1 can promote transcription of pro-inflammatory NFκB target genes through targeted chromatin remodeling (Ma, Ming et al. 2017). HMGB1 administration (i.c.v) has also been shown to cause depressive behavior (Lian, Gong et al. 2017), and HMGB1 inhibition reduces IL-1β induction by methamphetamine (Frank, Adhikary et al. 2016). Thus, HMGB1/IL-1β complex release may represent an acute activation upon a chronic more pro-inflammatory baseline state, making them an ideal therapeutic target.

We report findings in postmortem human hippocampus, whole mouse brain, and in rat hippocampal-entorhinal cortex slice culture consistent with ethanol inducing both HMGB1 and IL-1β in multiple species. Previous studies have found that chronic ethanol increases IL-1β in the cerebral cortex (Valles, Blanco et al. 2004, Qin, He et al. 2008) and cerebellum (Lippai, Bala et al. 2013), which are consistent with our current findings after acute ethanol. We now find that an acute binge ethanol dose induces IL-1β expression. Consequences of innate immune activation might vary by brain region. In the hippocampus innate immune activation can alter mood, neurogenesis, and memory regulation. Multiple studies have shown that neuroinflammation impairs neurogenesis (Ekdahl, Claasen et al. 2003, Fujioka and Akema 2010), and we have shown that IL-1β activation inhibits hippocampal neurogenesis (Zou and Crews 2012). Hippocampal neurogenesis is involved in learning and memory (Shors, Miesegaes et al. 2001), as well as mood regulation (Malberg, Eisch et al. 2000), with impaired neurogenesis contributing to anxiety and depression (Hill, Sahay et al. 2015). Further, hippocampal IL-1β is critical in these pathologies due to its role in memory acquisition (Goshen, Kreisel et al. 2007) and its requirement for stress-induced depression and suppression of neurogenesis (Goshen, Kreisel et al. 2008). Further, studies of epilepsy find HMGB1 and IL-1β contribute to seizure threshold (Moroso) and ethanol exposure and withdrawal are known to alter seizure threshold. Our findings of HMGB1/IL-1β complex formation and secretion in brain suggest these pathologies may also involve HMGB1/IL-1β complex signaling.

The mechanism by which HMGB1 in complex with IL-1β has enhanced potency is unclear. The ability of IL-1RA to block the action of the complexes, and the absence of a neuroimmune signal by HMGB1 at the 17nM concentration used in vitro, suggest that the primary signal at these concentrations is through the IL-1 receptor. HMGB1 could potentially allosterically enhance IL-1β binding to its receptor or increase on-time with the receptor (Figure 9D). Therapeutic interventions that target the release HMGB1/IL-1β complexes should be investigated for potential efficacy. Since IL-1β itself is needed for normal memory function, hybrid antibodies that target both HMGB1 and IL-1β might be optimal for reducing adverse immune activation without altering normal function. IL-1RA in our studies and anti-IL-1β antibodies in previous studies (Sha, Zmijewski et al. 2008) are effective at blocking the immune responses to HMGB1/IL-1 complexes. However, IL-1β itself serves important functions in normal conditions such as the regulation of LTP (Goshen, Kreisel et al. 2007, Prieto, Snigdha et al. 2015, Prieto and Cotman 2017). Thus, therapies directed at the immune mediating HMGB1/IL-1β complexes might target immune activation with less side effects than blocking all IL-1β function. Also, these antibodies could be beneficial for diagnostic use. Our findings suggest that conventional ELISAs for IL-1β do not detect IL-1β when it is in complex with other proteins, as we observed ~10-fold increased plasma IL-1β following acid purification, than we observed without purification.

In summary, we find that HMGB1/IL-1β complexes are increased in the hippocampus of postmortem human alcoholics, and that ethanol induces complex formation and release in vivo and in vitro respectively. These complexes cause enhanced neuroimmune activation and may represent novel immune targets for alcohol use disorders and other neuroimmune pathologies.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Western Blots of Flow through from Brain Co-IP. Brain tissue from control and ethanol treated mice were immunoprecipitated with an anti-HMGB1 antibody using the Catch and Release® kit. Flow through was assessed by western blot for IL-1β and HMGB1 (A) Western blots of the eluate of co-IP was performed and probed for IL-1β (800) and HMGB1 (700). A faint band was seen near 17kD which represents cleaved IL-1β that was bound to HMGB1. A more pronounced IL-1β+ band was sen at 31kD consistent with pro-IL-1β (B) Western blots of the flow was performed and probed for IL-1β and HMGB1. The immunoprecipitation for HMGB1 was efficient, as minimal HMGB1 remained in the flow through. IL-1β alone was not detected in the flow through.

Supplemental Figure 2: Ethanol increases HMGB1 in liver by ELISA. Mice were treated with ethanol (6g/kg, i.g). Liver protein was and ELISA performed to measure HMGB1. Western blot was performed to assess for the presence of higher molecular weight HMGB1+ bands (A) Ethanol caused a 1.4-fold increase in HMGB1 in the liver by ELISA at 12 hours post ethanol. N=4–11 mice per time point, 1-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. (B) Western Blot showed a band consistent with free HMGB1 was observed at 29kD. However, no band was seen at ~60–65kD. (C–D) Immunoprecipitation for HMGB1 and IL-1β was performed in liver. (C) IL-1β did not co-immunoprecipitate with HMGB1 in the liver. Western blots on the eluate for IL-1β and HMGB1 found HMGB1 in the eluate, but not IL-1β (D) Flow through was assessed by western blot for IL-1β and HMGB1. The immunoprecipitation for HMGB1 was very efficient, as minimal HMGB1 remained in the flow through. Bands consistent with uncleaved pro-IL-1β protein were seen in the liver flow through.

Supplemental Figure 3: Negative Control for Confocal Staining of Mouse Brain. Immunofluorescence was performed on mouse brain with appropriate secondary antibodies only (no primary antibodies). Diffuse low background staining was observed, with no nonspecific punctate, cytoplasmic staining.

Supplemental Figure 4: Entire Western Blots of Eluate and Flow through from Hippocampal Slice Culture (HEC) Media Co-IP. HEC slices were transfected with FLAG-HMGB1 as described in the methods and then treated with either saline, LPS (100ng/mL) or ethanol (100mM). Media was collected and immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody using the Catch and Release® kit. Eluate and Flow through were assessed by western blot for IL-1β and FLAG-HMGB1. (A) Entire blots of eluates probed for IL-1β and for HMGB1. Bands positive for IgG, pro-IL-1β, cleaved IL-1β isoforms and the Catch and Release® affinity ligand were observed as expected. The blot probed for FLAG-HMGB1 showed a band consistent with free FLAG_HMGB1 near 29kD. (B) Entire western blots of flow through. The immunoprecipitation for FLAG was efficient, as minimal FLAG-HMGB1 remained in the flow through. Cleaved IL-1β was not detected in the flow-through.

Supplemental Figure 5: Entire Western Blots for Co-Immunopreciptation of HMGB1 and IL-1β in Human Brain Tissue. Co-immunoprecipitation was performed for HMGB1 and IL-1β in postmortem human alcoholic hippocampus. Entire eluate and flow through for these samples are presented. (A) Entire blots of eluates probed for IL-1β and for HMGB1. Bands positive for IgG, pro-IL-1β, and light cleaved IL-1β bands as well as the Catch and Release® affinity ligand were observed as expected. The blot probed for FLAG-HMGB1 showed a band consistent with free HMGB1 near 29kD. (B) Entire western blots of flow through. The immunoprecipitation for HMGB1 was efficient, as minimal HMGB1 remained in the flow through. Small amounts of pro-IL-1β and cleaved IL-1β were also detected in the flow-through, indicating non-HMGB1 bound forms in human brain tissue as well.

Supplemental Figure 6: IgG controls for mouse, human, and hippocampal slice culture media. Co-immunoprecipitation was performed for HMGB1 and IL-1β in each tissue with rabbit IgG substituted for the HMGB1 antibody. Entire eluate and flow through for these samples are presented. (A) No cleaved IL-1β was found in the eluate from any of the tissues. Some pro-IL-1β was found in the eluate from hippocampal slice culture media indicating some degree of non-specific association with the pro-form of IL-1β. (B) Western blots of flow through for HMGB1 and IL-1β showed numerous bands consistent with a lack of binding of HMGB1 or IL-1β non-specifically to the control IgG.

Highlights.

HMGB1 and IL-1β are induced in the brain and plasma in response to ethanol

HMGB1 and IL-1β form potent immune complexes in the human alcoholic brain

HMGB1 and IL-1β heterocomplexes as secreted in response to ethanol

Immunogenic HMGB1/IL-1β may represent a novel immune target for alcoholism

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the New South Wales Brain Bank for their provision of the human alcoholic brain samples. We would also like to thank Michael Chua for his assistance with confocal microscopy. Funding: NIAAA AA024829, AA019767, AA11605, AA007573, and AA021040

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adachi J, Mizoi Y, Fukunaga T, Ogawa Y, Ueno Y, Imamichi H. Degrees of alcohol intoxication in 117 hospitalized cases. J Stud Alcohol. 1991;52(5):448–453. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrei C, Dazzi C, Lotti L, Torrisi MR, Chimini G, Rubartelli A. The secretory route of the leaderless protein interleukin 1beta involves exocytosis of endolysosome-related vesicles. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10(5):1463–1475. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.5.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bala S, Marcos M, Gattu A, Catalano D, Szabo G. Acute binge drinking increases serum endotoxin and bacterial DNA levels in healthy individuals. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnay-Verdier S, Gaillard C, Messmer M, Borde C, Gibot S, Marechal V. PCA-ELISA: a sensitive method to quantify free and masked forms of HMGB1. Cytokine. 2011;55(1):4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belov L, Meher-Homji V, Putaswamy V, Miller R. Western blot analysis of bile or intestinal fluid from patients with septic shock or systemic inflammatory response syndrome, using antibodies to TNF-alpha, IL-1 alpha and IL-1 beta. Immunol Cell Biol. 1999;77(1):34–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1999.00796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya A, Derecki NC, Lovenberg TW, Drevets WC. Role of neuroimmunological factors in the pathophysiology of mood disorders. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2016;233(9):1623–1636. doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4214-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi ME. HMGB1 loves company. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86(3):573–576. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1008585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borth W, Luger TA. Identification of alpha 2-macroglobulin as a cytokine binding plasma protein. Binding of interleukin-1 beta to "F" alpha 2-macroglobulin. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(10):5818–5825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castiglioni A, Canti V, Rovere-Querini P, Manfredi AA. High-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) as a master regulator of innate immunity. Cell Tissue Res. 2011;343(1):189–199. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-1033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Li G, Liu Y, Werth VP, Williams KJ, Liu ML. Translocation of Endogenous Danger Signal HMGB1 From Nucleus to Membrane Microvesicles in Macrophages. J Cell Physiol. 2016;231(11):2319–2326. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman LG, Jr, Jarskog LF, Moy SS, Crews FT. Deficits in adult prefrontal cortex neurons and behavior following early post-natal NMDA antagonist treatment. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;93(3):322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman LG, Jr, Zou J, Crews F. Microglial-derived miRNA Let-7 and HMGB1 contribute to ethanol-induced neurotoxicity via TLR7. J Neuroinflammation. 2017 doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0799-4. In Press(In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman LG, Jr, Zou J, Crews FT. Microglial-derived miRNA let-7 and HMGB1 contribute to ethanol-induced neurotoxicity via TLR7. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0799-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Lawrimore CJ, Walter TJ, Coleman LG. The role of neuroimmune signaling in alcoholism. Neuropharmacology. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Qin L, Sheedy D, Vetreno RP, Zou J. High mobility group box 1/Toll-like receptor danger signaling increases brain neuroimmune activation in alcohol dependence. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(7):602–612. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Vetreno RP. Mechanisms of neuroimmune gene induction in alcoholism. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2016;233(9):1543–1557. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-3906-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Zou J, Qin L. Induction of innate immune genes in brain create the neurobiology of addiction. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25(Suppl 1):S4–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedova I, Harding A, Sheedy D, Garrick T, Sundqvist N, Hunt C, Gillies J, Harper CG. The importance of brain banks for molecular neuropathological research: The New South Wales Tissue Resource Centre experience. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10(1):366–384. doi: 10.3390/ijms10010366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont N, Jiang S, Pilli M, Ornatowski W, Bhattacharya D, Deretic V. Autophagy-based unconventional secretory pathway for extracellular delivery of IL-1beta. EMBO J. 2011;30(23):4701–4711. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekdahl CT, Claasen JH, Bonde S, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. Inflammation is detrimental for neurogenesis in adult brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(23):13632–13637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2234031100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MG, Adhikary S, Sobesky JL, Weber MD, Watkins LR, Maier SF. The danger-associated molecular pattern HMGB1 mediates the neuroinflammatory effects of methamphetamine. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;51:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MG, Weber MD, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Stress-induced neuroinflammatory priming: A liability factor in the etiology of psychiatric disorders. Neurobiol Stress. 2016;4:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka H, Akema T. Lipopolysaccharide acutely inhibits proliferation of neural precursor cells in the dentate gyrus in adult rats. Brain Res. 2010;1352:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardella S, Andrei C, Ferrera D, Lotti LV, Torrisi MR, Bianchi ME, Rubartelli A. The nuclear protein HMGB1 is secreted by monocytes via a non-classical, vesicle-mediated secretory pathway. EMBO Rep. 2002;3(10):995–1001. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Antoine DJ, Lu Y, Arriazu E, Leung TM, Klepper AL, Branch AD, Fiel MI, Nieto N. High mobility group box-1 (HMGB1) participates in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease (ALD) J Biol Chem. 2014;289(33):22672–22691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.552141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshen I, Kreisel T, Ben-Menachem-Zidon O, Licht T, Weidenfeld J, Ben-Hur T, Yirmiya R. Brain interleukin-1 mediates chronic stress-induced depression in mice via adrenocortical activation and hippocampal neurogenesis suppression. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13(7):717–728. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshen I, Kreisel T, Ounallah-Saad H, Renbaum P, Zalzstein Y, Ben-Hur T, Levy-Lahad E, Yirmiya R. A dual role for interleukin-1 in hippocampal-dependent memory processes. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32(8–10):1106–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu L, Okada Y, Clinton SK, Gerard C, Sukhova GK, Libby P, Rollins BJ. Absence of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 reduces atherosclerosis in low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Mol Cell. 1998;2(2):275–281. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill AS, Sahay A, Hen R. Increasing Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis is Sufficient to Reduce Anxiety and Depression-Like Behaviors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(10):2368–2378. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodes GE, Kana V, Menard C, Merad M, Russo SJ. Neuroimmune mechanisms of depression. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(10):1386–1393. doi: 10.1038/nn.4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori O, Brett J, Slattery T, Cao R, Zhang J, Chen JX, Nagashima M, Lundh ER, Vijay S, Nitecki D, et al. The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) is a cellular binding site for amphoterin. Mediation of neurite outgrowth and co-expression of rage and amphoterin in the developing nervous system. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(43):25752–25761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V, Latz E. Critical functions of priming and lysosomal damage for NLRP3 activation. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40(3):620–623. doi: 10.1002/eji.200940185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hreggvidsdottir HS, Ostberg T, Wahamaa H, Schierbeck H, Aveberger AC, Klevenvall L, Palmblad K, Ottosson L, Andersson U, Harris HE. The alarmin HMGB1 acts in synergy with endogenous and exogenous danger signals to promote inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86(3):655–662. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0908548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyel PA. How is inflammation initiated? Individual influences of IL-1, IL-18 and HMGB1. Cytokine. 2014;69(1):136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamkanfi M, Sarkar A, Vande Walle L, Vitari AC, Amer AO, Wewers MD, Tracey KJ, Kanneganti TD, Dixit VM. Inflammasome-dependent release of the alarmin HMGB1 in endotoxemia. J Immunol. 2010;185(7):4385–4392. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrimore C, Crews F. Ethanol, TLR3, and TLR4 agonists have unique innate immune responses in neuron-like SH-SY5Y and microglia-like BV2. Alcoholism Clinical Experimental Research. 2017 doi: 10.1111/acer.13368. In Press(In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq S, De Saeger C, Delzenne N, de Timary P, Starkel P. Role of inflammatory pathways, blood mononuclear cells, and gut-derived bacterial products in alcohol dependence. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;76(9):725–733. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian YJ, Gong H, Wu TY, Su WJ, Zhang Y, Yang YY, Peng W, Zhang T, Zhou JR, Jiang CL, Wang YX. Ds-HMGB1 and fr-HMGB induce depressive behavior through neuroinflammation in contrast to nonoxid-HMGB1. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;59:322–332. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippai D, Bala S, Petrasek J, Csak T, Levin I, Kurt-Jones EA, Szabo G. Alcohol-induced IL-1beta in the brain is mediated by NLRP3/ASC inflammasome activation that amplifies neuroinflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94(1):171–182. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1212659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthi A, Luscher C. Pathological circuit function underlying addiction and anxiety disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(12):1635–1643. doi: 10.1038/nn.3849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Ming Z, Gong AY, Wang Y, Chen X, Hu G, Zhou R, Shibata A, Swanson PC, Chen XM. A long noncoding RNA, lincRNA-Tnfaip3, acts as a coregulator of NF-kappaB to modulate inflammatory gene transcription in mouse macrophages. FASEB J. 2017;31(3):1215–1225. doi: 10.1096/fj.201601056R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie A, Wilson HL, Kiss-Toth E, Dower SK, North RA, Surprenant A. Rapid secretion of interleukin-1beta by microvesicle shedding. Immunity. 2001;15(5):825–835. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malberg JE, Eisch AJ, Nestler EJ, Duman RS. Chronic antidepressant treatment increases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2000;20(24):9104–9110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09104.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroso M, Balosso S, Ravizza T, Liu J, Bianchi ME, Vezzani A. Interleukin-1 type 1 receptor/Toll-like receptor signalling in epilepsy: the importance of IL-1beta and high-mobility group box 1. J Intern Med. 2011;270(4):319–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall SA, Casachahua JD, Rinker JA, Blose AK, Lysle DT, Thiele TE. IL-1 receptor signaling in the basolateral amygdala modulates binge-like ethanol consumption in male C57BL/6J mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;51:258–267. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MM, Wright CL. Convergence of Sex Differences and the Neuroimmune System in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81(5):402–410. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montesinos J, Pascual M, Pla A, Maldonado C, Rodriguez-Arias M, Minarro J, Guerri C. TLR4 elimination prevents synaptic and myelin alterations and long-term cognitive dysfunctions in adolescent mice with intermittent ethanol treatment. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;45:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel W, Rabouille C. Mechanisms of regulated unconventional protein secretion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(2):148–155. doi: 10.1038/nrm2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]