Abstract

Background

Women with chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes and hypertension, have a higher risk of pregnancy-related complications compared with women without medical conditions and should be offered contraception if desired. Although evidence based guidelines for contraceptive selection in the presence of medical conditions are available via the United States Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC), these guidelines are underutilized. Research also supports the use of decision tools to promote shared decision making between patients and providers during contraceptive counseling.

Objective

The overall goal of the MiHealth, MiChoice project is to design and implement a theory-driven, Web-based tool that incorporates the US MEC (provider-level intervention) within the vehicle of a contraceptive decision tool for women with chronic medical conditions (patient-level intervention) in community-based primary care settings (practice-level intervention). This will be a 3-phase study that includes a predesign phase, a design phase, and a testing phase in a randomized controlled trial. This study protocol describes phase 1 and aim 1, which is to determine patient-, provider-, and practice-level factors that are relevant to the design and implementation of the contraceptive decision tool.

Methods

This is a mixed methods implementation study. To customize the delivery of the US MEC in the decision tool, we selected high-priority constructs from the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research and the Theoretical Domains Framework to drive data collection and analysis at the practice and provider level, respectively. A conceptual model that incorporates constructs from the transtheoretical model and the health beliefs model undergirds patient-level data collection and analysis and will inform customization of the decision tool for this population. We will recruit 6 community-based primary care practices and conduct quantitative surveys and semistructured qualitative interviews with women who have chronic medical conditions, their primary care providers (PCPs), and clinic staff, as well as field observations of practice activities. Quantitative survey data will be summarized with simple descriptive statistics and relationships between participant characteristics and contraceptive recommendations (for PCPs), and current contraceptive use (for patients) will be examined using Fisher exact test. We will conduct thematic analysis of qualitative data from interviews and field observations. The integration of data will occur by comparing, contrasting, and synthesizing qualitative and quantitative findings to inform the future development and implementation of the intervention.

Results

We are currently enrolling practices and anticipate study completion in 15 months.

Conclusions

This protocol describes the first phase of a multiphase mixed methods study to develop and implement a Web-based decision tool that is customized to meet the needs of women with chronic medical conditions in primary care settings. Study findings will promote contraceptive counseling via shared decision making and reflect evidence-based guidelines for contraceptive selection.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03153644; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03153644 (Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6yUkA5lK8)

Keywords: contraception, mobile apps, birth control, primary care physicians, implementation science, decision support techniques, chronic disease, multiple chronic conditions, qualitative research

Introduction

Quality Gaps in Contraceptive Care

Access to family planning services to prevent unintended pregnancies is one of the leading health indicators for Healthy People 2020 [1]. Unintended pregnancies account for half of all US pregnancies [2] and are associated with adverse outcomes for women and children, such as maternal depression and low birth weight, respectively [3,4]. In 2008, US expenditures for live births resulting from unintended pregnancies were US $12.5 billion [5]. In 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the US Office of Population Affairs jointly recommended an increase in the volume and quality of family planning services across all health care sectors, including primary care, to address this unmet public health need [6]. The Office of Population Affairs subsequently released contraceptive quality measures that assess the percentage of reproductive-aged fertile women who are provided moderately effective and highly effective contraceptive methods [7]. The National Quality Forum formally endorsed these measures in 2017, and the development of a patient-reported measure of contraceptive care is in progress [7]. There is a timely and critical need to disseminate and implement evidence-based interventions to meet these contraceptive quality measures and improve reproductive health outcomes.

Implications for Women With Chronic Medical Conditions

Women with chronic medical conditions (eg, diabetes and hypertension) have a higher rate of pregnancy-related complications [8-11] and death compared with women without these conditions [12,13]. The most prevalent chronic medical conditions (hereafter called “chronic conditions”) among reproductive-age women have risen over the last 10 years and include obesity (24.7%), asthma (16.2%), high cholesterol (13%), hypertension (10%), and diabetes (2.9%) [14]. Expanded definitions of chronic conditions that include psychiatric conditions estimate that women with chronic conditions comprise up to 45% of reproductive age women seen in primary care [15,16]. Studies have raised concerns that adult women with chronic conditions are at greater risk for unplanned pregnancy [17] as they are more likely to not use any contraceptive method, underutilize the most effective methods, and rely upon the least effective methods compared with the general population of reproductive-aged women [18-21]. Women with chronic conditions are often prescribed medications that can cause fetal defects [22,23], and those who do not desire pregnancy should be offered contraceptive options. Contraceptive counseling should include an explanation of potential beneficial or adverse impact of a method on their conditions and interactions with ongoing drug therapy.

Missed Opportunities and Barriers to Contraceptive Care in Primary Care

Women with chronic conditions most frequently see primary care providers (PCPs) for their health management [24]; these visits are windows of opportunity to address contraception within the context of ongoing medical care [25]. PCPs are well situated to address the contraceptive needs of women with chronic conditions, but the time constraints of office visits and incomplete provider knowledge are commonly cited barriers to doing so [26-28]. Although family planning is a required part of training for most PCPs, contraceptive knowledge is lower among PCPs compared with obstetrics and gynecology providers [27,28]; this is not surprising given the greater intensity of training and exposure to women’s health care among obstetrics and gynecology providers.

Implementation of Evidence-Based Contraceptive Guidelines From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

In 2010, the CDC released the United States Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC), which was adapted directly from the World Health Organization’s MEC to meet the unique needs of US patients. The US MEC provides guidance to clinicians regarding the selection of contraceptive methods in the presence of specific chronic conditions (eg, seizures) and personal characteristics (eg, age) [29] and is revised on a continual basis. In 2011, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists formally endorsed use of the US MEC for “clinicians providing family planning services for women, especially women with chronic conditions” [30] as an effort to promote national-level dissemination and implementation of evidence-based contraceptive practices. However, there is a significant gap between the US MEC and reported clinical recommendations, particularly with respect to the intrauterine device and the implant—the most effective long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) [26,28,31-34]. LARC methods are estrogen-free and safe for the vast majority of women, including those with conditions that may preclude the use of estrogen (eg, cardiac disease) [35-37]. It is critical to correct PCP misconceptions about LARC eligibility so that they do not unnecessarily prevent LARC use among women with chronic conditions, who are otherwise appropriate candidates [36], thus placing them at risk for unintended pregnancy.

Evidence-Based Contraceptive Counseling With Electronic Decision Aids

Studies have shown that provider recommendations have a significant and positive impact on patient initiation and selection of a contraceptive method [38-40]. However, the provision of generic contraceptive information alone is insufficient. Prior literature highlights the importance of individualized contraceptive counseling [41-43] via a shared decision-making process [44-47], defined as an interactive process through which providers and patients communicate and arrive at a mutually agreeable decision [48]. Decisions aids are clinical tools designed to support patient-centered communication via shared decision making rather than provide paternalistic or generic information [41,49]. Prior contraceptive decision aids have been developed for use on electronic tablet or computer-based platforms across multiple geographic regions, practice settings, and patient populations and have been associated with improved patient involvement [50], decreased decisional conflict, increased patient knowledge [51], and increased contraceptive use [45,52]. Patients have reported numerous advantages to a Web-based platform over paper, including the interactive nature of the interface and the ability to compare contraceptive methods using filters and sorting options [53,54]. Furthermore, patients appreciated the use of a decision tool before a clinical visit to help them narrow down their contraception options and prepare questions for their providers [53].

Rationale for Mixed Methods Study Design

The underlying rationale for collecting, integrating, and analyzing both qualitative and quantitative data are multifold: (1) quantitative data collected from self-administered survey items will provide descriptive statistics to allow for comparison with other practice settings and populations, (2) qualitative interviews will provide a deeper understanding of the lived experiences of women with chronic conditions and their primary care teams with respect to receiving and providing contraceptive services, respectively, (3) qualitative interviews provide an opportunity to immediately expand upon close-ended quantitative survey items that warrant further investigation [55], (4) leveraging the complementary nature of quantitative data and qualitative data maximizes our capacity to assess a broader range of theoretical constructs and contextual factors than if quantitative or quantitative methods were used alone [56], (5) collecting data via multiple methods (observations, interviews, surveys) improves the robustness and credibility of our findings [57].

The Use of Theory and Implementation Science to Develop a Patient-Centered Intervention for Use in Usual Care Settings

To ensure the development of a patient-centered tool that explicitly upholds patient autonomy in decision making, we created a conceptual model that draws upon principles from reproductive justice theory and health behavior theories. This conceptual model will provide a preliminary prototype for the decision tool, which will be modified iteratively during this study phase. To develop an intervention that is contextualized for use in real-world clinical practices, our study design is informed by implementation science, an emerging field of methods and approaches that address the challenges of implementing health interventions in usual practice settings.[58] We use selected constructs from 2 frameworks commonly used in implementation science: the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [59] and the Theoretical Domains Framework, to guide data collection and analysis on the practice and provider level, respectively.

The overall goal of this mixed methods implementation project, the MiHealth MiChoice study, is to design and implement a theory-driven, Web-based contraceptive decision tool that can be accessed on an electronic tablet or computer before a clinical visit by women with chronic conditions who are seen in primary care settings. The feature of this tool that sets it apart from prior decision aids is that it will be tailored to factor in the personal preferences and medical history of a specific individual in a manner that also reflects evidence-based guidelines. The development and testing of this tool will occur over 3 phases (a predevelopment, development, and testing phase). The aim of this study protocol for phase 1 is to identify multilevel contextual factors that should drive the design and implementation of the contraceptive decision tool and explain subsequent study outcomes [60].

Methods

Overall Study Design

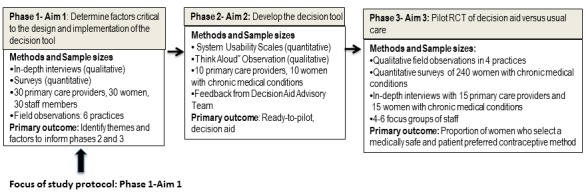

This mixed methods implementation study consists of 3 phases. This protocol focuses on phase 1, which is to identify the most critical patient-, provider-and practice-level factors that should inform the design and implementation of the decision-support tool. In phase 2, we will work with an expert health informatics team and an advisory council comprising patients, providers, and decision aid experts to build the Web-based decision tool that is accessible via a secured weblink from a computer or handheld tablet. Findings from phase 1 and a novel conceptual model (described in Figure 1 below) will inform iterative prototypes of the decision tool. In phase 3, the decision tool will be compared with usual care in a randomized controlled trial. We have received ethics approval for this study protocol by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (HUM00128060).

Figure 1.

Multiphase mixed methods design. PCP: primary care provider; RCT: randomized controlled trial; CC: chronic condition.

Phase 1 Study Design

This is a convergent mixed methods design phase that focuses primarily on qualitative data collection and analysis with concurrent quantitative data collection and analysis. We will conduct semistructured, qualitative interviews of patients, PCPs, and practice staff members. All study participants will complete quantitative written surveys or electronic surveys via Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) before their qualitative interviews. The quantitative survey items complement the qualitative interview guide with the goal of obtaining maximal depth and breadth of understanding of each construct. Semistructured field observations in practices and collection of practice artifacts (eg, clinical protocols and patient intake forms) will further diversify our data sources and optimize data triangulation, which in turn will reduce the risk of systematic biases based on reported behaviors and experiences alone [61].

Sampling Strategy, Eligibility, and Recruitment

Practices

To balance similarity and variation across practices, providers, and patients, we will use a combination of purposeful sampling techniques as described by Palinkas and colleagues [62]. Eligible practices include practices that identify as family medicine, internal medicine, internal medicine-pediatric, or any combination of these. First, we will use criterion sampling to select individuals who have experiences that are relevant to the phenomenon of interest [62]; for this study, we aim to select practices for which a contraceptive intervention is both clinically relevant and feasible to implement. Because LARC methods (intrauterine device and implant) are the most effective reversible methods and medically appropriate for the vast majority of women with chronic conditions [36,37,63], we will recruit practices that either provide LARC or assist with referrals for LARC. Therefore, eligible practices must have: (1) one or more providers who currently offer prescription contraception (eg, oral contraceptive pills), and (2) informal or formal processes to refer patients who desire LARC methods to another site or provide LARC methods on site. To achieve maximum variation in practice attributes that are associated with variations in contraceptive practice [31,64], clinical sites will be sampled to reflect a range of location (urban, suburban, and rural practices), a balance between private practices and practices with federal designations (federally qualified health centers, rural health center, medically underserved areas), and diversity in the racial/ethnic background of patients. Thus, maximum variation sampling aims to achieve breadth in sampling and can highlight differences between practices. To complement this approach, we will also use snowball sampling such that participating practices suggest other practices for recruitment; this approach tends to select practices that share characteristics and thus will help to achieve depth of understanding of similar practices [62]. We will recruit practices through The Great Lakes Research Into Practice Network, a statewide practice-based research network that is recognized by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [65].

Sample Size

To achieve the depth and variation in practices as described above, we aim to enroll 6 clinical sites. For individual qualitative interviews, prior literature has documented that 6 to 12 interviews per homogeneous group provide sufficient qualitative data to reach saturation, the point at which analysis produces no new information, or disconfirming or confirming evidence [55,66]. On the basis of the sampling strategy described, we aim to enroll 30 patients, 30 PCPs, and 30 staff members (nurses, medical assistants, and administrative staff). Our definitions of homogenous groups are summarized below and in Multimedia Appendix 1. Purposeful sampling will be driven by this matrix such that the perspectives of individuals in each category are represented in qualitative interview data with the goal of data saturation. We expect this category to evolve based upon patient population characteristics in recruited practices.

Practice Members (Primary Care Practices and Staff)

Eligible practice members must be aged 18 years or older, English-speaking, able to give informed consent, and be indirectly or directly involved with patient care. PCPs must be physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, or certified nurse midwives, who currently provide preventive health and management of chronic conditions to reproductive-aged women [62]. To complement criterion sampling as described above, we seek maximal variation [62] in PCPs’ contraceptive practices and will sample individuals who: (1) do not provide prescription contraception (eg, oral contraceptive pills), (2) provide prescription contraception but do not insert LARC devices, or (3) provide prescription contraception and insert LARC devices. For practice staff members other than PCPs, we aim to gather staff perspectives regarding contraceptive services and interventions that may differ based upon their primary responsibilities and context of patient interaction: (1) director or manager (clinical director, administrative director, nurse manager), (2) work with PCPs during clinical visits (nurses, medical assistants, licensed practical nurses), and (3) other services (social work, complex care management, pharmacist, behavioral counselor). A designated practice liaison (eg, medical director, office manager) will assist the study team to identify eligible practice members and extend invitations for study participation.

Patients

Eligible patients must be women aged 18 to 50 years, fertile, English-speaking, and able to provide informed consent. They must also meet at least one of the following criteria: (1) a documented medical condition or multiple medical conditions being actively managed (on medication or requiring at least 2 visits a year), (2) a documented past medical condition or multiple medical conditions which would pose a significant risk to health during pregnancy (eg, past lung clot), or (3) current use of any drugs that are Pregnancy Category D or Category X medications. This definition expands upon guidance provided by the Department of Health and Human Services [67] as well as informed by pilot interviews with 15 PCPs (unpublished data). To obtain a range of perspectives, we aim to sample approximately equal numbers of women in the following groups that consist of conditions commonly encountered in primary care [68], conditions that frequently coexist together, or are managed with similar behavioral approaches and medications. Furthermore, we will focus on conditions for which there is evidence-based guidance regarding contraceptive selection in the CDC US MEC [69]. The following groups are described in detail in Multimedia Appendix 1: (1) psychiatric conditions, (2) metabolic and endocrine conditions, and (3) neurologic conditions. We will include an other group to capture women with less common conditions that nevertheless have a significant impact on pregnancy-related morbidity and mortality and contraceptive eligibility. The principal investigator (JW), who is a primary care specialist and a family planning expert, will review each participant’s medical history and medications, in conjunction with the designated practice liaison, to ensure that eligibility criteria have been met.

The designated practice liaison in each practice will assist the study team in identifying patients who meet the eligibility criteria. With the permission of their PCPs, recruitment letters will be sent to potentially eligible patients followed up by up to 3 phone calls.

Context Assessment Frameworks to Guide Implementation (Practice and Provider Level)

Dehlendorf and colleagues recently described the development and testing of a tablet-based contraceptive decision aid that underwent rigorous cognitive testing [70] among patients in a safety net clinic. Our adaptation of this decision aid model will be sensitized by the application of our data to selected constructs from the CFIR, a typology of 5 major domains and associated constructs to assess context [59]. We chose CFIR because it identifies constructs at the practice and provider level that are universally relevant to successful implementation of a new intervention in clinical practice and can be tailored to the context of contraception. Furthermore, we anticipate that the use of CFIR will facilitate the collection of qualitative and quantitative data in a harmonized and efficient manner. Because the proposed intervention integrates clinical decision support for individual health providers, we also adapted constructs from the Theoretical Domains Framework to systematically identify determinants of clinical behavior change among PCPs [71]. We created a mixed methods theory-data matrix (see Multimedia Appendices 2-4), CSIR constructs and definitions by Damschroder et al [59]) to summarize how qualitative data (derived from practice observation, artifacts, and interviews) and quantitative data (derived from surveys) map to CFIR and Theoretical Domains Framework constructs (see Multimedia Appendices 2-4).

Conceptual Model to Guide Development of the Decision Tool (Patient-Level)

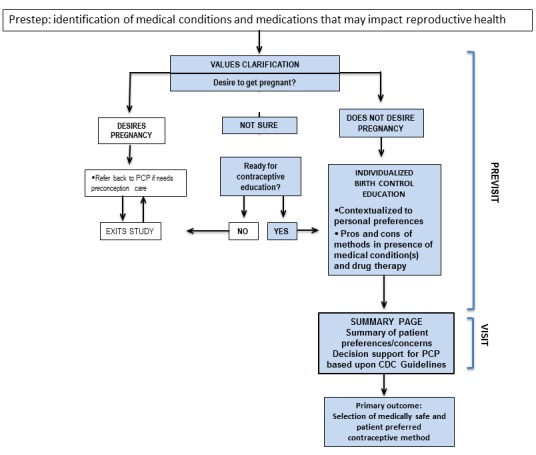

In a systematic review, Wyatt and colleagues identified 32 unique characteristics among 19 decision aids and classified them into 4 overarching categories: method effect, mechanistic, social/normative, and practical [72]. Among these attributes, studies have shown that women prioritize knowledge regarding mechanism of action [44], contraceptive effectiveness, safety, and side effects [73]. Using the tablet-based decision aid described by Dehlendorf as the prototype model [70], we will customize the above high-priority attributes for this patient population. Using a drop-down menu function, women will first provide their basic health history, including age, smoking status, medical conditions, and medications. We will then elicit patient preferences, guided by a conceptual model that incorporates a synthesis of constructs from reproductive justice theory, behavioral health theories, and evidence-based counseling techniques such as motivational interviewing and values clarification (Figure 2). One of the central tenets of reproductive justice is that people should be equally afforded the right to have a child and parent as well as the right to not have a child [74]. In accordance with this principle, we assert that a patient-centered contraceptive tool must be designed to prevent unconscious or conscious reproductive coercion, particularly toward individuals from marginalized communities. This concern is based upon the disturbing legacy of compulsory sterilization programs that targeted women of color, poor women, women with disabilities, and immigrant women in multiple US states throughout the twentieth century [75] and even as recently as 2010 in California [76]. Therefore, the model explicitly avoids presumptions about the patient’s feelings regarding pregnancy and childbearing and starts with a values clarification [77] question by asking the patient about her current feelings regarding pregnancy and parenting.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model to guide design of decision tool. PCP: primary care provider; CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Adapting a principle from the transtheoretical model [78], the patient will receive recommendations that are “matched” to her current pregnancy desires. If she does not want to get pregnant and indicates she is ready for contraceptive education, she will proceed through a responsive algorithm based upon her personal preferences, concerns, and prior contraceptive experiences. Constructs from the health beliefs model [79] will be operationalized to provide her information regarding the potential impact of her chronic condition on her reproductive health and vice versa, as well as individualized pros and cons of different contraceptive methods. The decision tool will summarize her preferences for methods, concerns she may want to discuss with her PCP, and embed clinical decision support for the PCP based upon the US MEC Guidelines (eg, patient has severe diabetes and should not use estrogen). This information will be made available in paper or electronic form to serve as a template for provider-patient discussion during the office visit.

If the patient indicates she desires pregnancy, she is advised to return to her PCP for preconception counseling and exits the study at this time. If the patient expresses ambivalence regarding pregnancy, the decision aid assesses if she is ready for contraceptive education, and if so, she proceeds through the contraceptive algorithm as outlined above.

Data Collection

Trained research assistants (RA) will spend 2 to 3 days at each clinical site to collect practice-specific data using a Practice Environment Template (PET), a semistructured checklist adapted from prior work by Crabtree and colleagues [80] and Jaén and colleagues [81]. The PET cues the RA to record observations of routine office activities, with a focus on clinical flow and processes relevant to contraceptive services. These data will provide a more complete and nuanced description of “what is happening on ground” and identify data that participants may not report on surveys or during interviews. The designated practice liaison will complete the Practice Information Form, a 29-item survey, also modified from prior work [80,81], that consists of multiple choice and open response items regarding practice demographics, pay structure, preventive and reproductive health services offered, and contraceptive methods offered.

All participants (staff, PCPs, and patients) will fill out a written or electronic (via Qualtrics, Provo, UT) quantitative survey before the face-to-face in-depth interview. There are 3 surveys: (1) a 34-item Patient Survey, (2) a 19-item Provider Survey (for PCPs), and (3) a 13-item Staff Survey (for practice members other than PCPs). Participants will be interviewed in a quiet, private space designated by each practice. Interviews are audiotaped with the participants’ permission and informed consent. We will conduct “member checking” with participants who agree to be contacted after the interview. This qualitative technique, also referred to as respondent validation, helps improve the accuracy, credibility, and transferability of research findings as well as empower participants to verify or modify the final interpretations of the data [61]. Member-checking should be undertaken with caution to minimize the risk of participant discomfort and ensure anonymity [82]. Therefore, we will share general themes and aggregated group data rather than specific quotes from individuals. All participants who complete an in-depth interview will receive a US $30 gift card as a token of appreciation for their time.

Data Analysis

All interview audiotapes will be transcribed verbatim. Qualitative analysis is an iterative process during which investigators go through cycles of reading, summarizing, and re-reading data [83,84]. The qualitative team is composed of 4 individuals from different professional backgrounds and research disciplines, including family medicine, dentistry, epidemiology, and health behavior. Though all team members identify as female, they vary in age, sexual orientation, religious background, and race/ethnicity. The interview transcripts will be uploaded and organized using MAXQDA software (VERBI GmbH, Berlin, Germany Version 12.3.1). We will conduct analysis through a series of iterative steps adapted from techniques described by Marshall and Rossman [85]. First, each team member will review several transcripts independently and code the content of each transcript. Because our research design is driven by predetermined theoretical constructs and research aims, our initial coding will be done with a theory-generated code template [86]. In vivo coding will also occur as new themes emerge from the interviews [85]. The team members will discuss, compare, and reconcile differences in coding and create a consensus code template, which will then be used to code the remainder of transcripts. Analysis of semistructured observations and practice artifacts proceeds in similar manner as described for interview transcripts. Themes and patterns will be identified and synthesized, using the preidentified theoretical constructs as a guide (Multimedia Appendices 2-4), as well as new codes and themes as they emerge. To increase the trustworthiness of our qualitative findings, we will triangulate our qualitative findings on multiple levels [54]: (1) methodological triangulation, by comparing and integrating with quantitative survey data, (2) data triangulation, by comparing and contrasting data obtained via interviews, surveys, observations, and artifacts, and (3) theoretical triangulation, by gathering multiple perspectives of the same phenomenon (patient-, provider-, practice-level perspectives). Data collection continues until saturation is reached, or until we no longer identify new or disconfirming or confirming data [84] with respect to the original research aim. Quantitative survey data will be summarized with simple descriptive statistics (frequencies, means, and SDs). We will conduct bivariate analyses with Fisher exact test to explore the following relationships: (1) demographic traits of providers and their contraceptive recommendations and practices, (2) practice attributes and providers’ contraceptive recommendations and practices, (3) the presence of different chronic conditions and current pregnancy desires among women, and (4) the presence of different chronic conditions and current contraceptive use among women. As described by Fetters [60], we will merge the quantitative and qualitative strands of data by identifying content from both datasets to compare, contrast, and synthesize. A final interpretation will summarize to what extent and how the results from the qualitative and quantitative data contribute to the identification of patient-, provider-, and practice-level factors that will then shape the design and implementation of the decision tool.

Results

Enrollment of patients and providers in community-based primary care practices in Michigan is underway. Upon completion of this first study phase, the findings will be used to inform design of the contraceptive decision tool for testing in a future randomized controlled trial. The results of this study will be published in a peer-reviewed journal and presented at scientific conferences.

Discussion

The study design and proposed intervention have several strengths. First, we are collecting multilevel qualitative and quantitative data to gain a comprehensive and deep understanding of the experiences of and interactions among patients, providers, and staff. Constructs from implementation science theory and behavioral health theories drive data collection and analysis. To organize this large volume of data, we employ a rigorous mixed methods design and data integration procedures. A potential weakness of this study is that practices are limited to Michigan, which has a lower prevalence of ethnic and racial minorities than more populous states. However, we will recruit practices that have greater representation of underrepresented groups to mitigate this concern. We also anticipate challenges associated with practice-based research, including efficient recruitment and coordination of research practices with multiple practices outside our institution. The support of a locally based and established state-wide primary care network and previously established relationships between our institution and community partners will be critical to these processes.

This protocol describes the first phase of a multiphase design and implementation of a theory-driven intervention that incorporates customized decision tool attributes and embeds targeted US MEC recommendations to meet the contraceptive needs of women with chronic medical conditions in primary care settings. The study findings will provide critical knowledge regarding the feasibility and best approaches to implement the intervention in real-world primary care settings with the goal of promoting shared decision-making and evidence-based guidelines.

Acknowledgments

JW receives support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) under award number 1K23HD084744-01A1. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review and approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Abbreviations

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CFIR

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

- LARC

long-acting reversible contraceptives

- PCP

primary care provider

- PET

Practice Environment Template

- US MEC

United States Medical Eligibility Criteria

Qualitative sampling matrix.

Mixed methods theory data matrix: mapping data to Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) inner setting constructs.

Mixed methods theory data matrix: mapping data to Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) outer setting and intervention constructs.

Mixed methods theory data matrix: mapping data to Theoretical Domains Framework (TDR) constructs.

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: JW, LD, MF, BZF, BC, SH, and JC contributed to key aspects of the study design, theoretical framework, or conceptual model. JW, MK, ST, and JF developed the survey instruments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Office of Disease Prevention Health Promotion 2014. [2017-12-10]. Healthy people 2020 leading health indicators: progress update https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/leading-health-indicators/Healthy-People-2020-Leading-Health-Indicators%3A-Progress-Update .

- 2.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the United States, 2001-2008. Am J Public Health. 2014 Feb;104(Suppl 1):S43–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng D, Schwarz EB, Douglas E, Horon I. Unintended pregnancy and associated maternal preconception, prenatal and postpartum behaviors. Contraception. 2009 Mar;79(3):194–8. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.09.009.S0010-7824(08)00457-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D'Angelo DV, Gilbert BC, Rochat RW, Santelli JS, Herold JM. Differences between mistimed and unwanted pregnancies among women who have live births. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36(5):192–7. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.192.04.3619204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sonfield A, Kost K, Gold RB, Finer LB. The public costs of births resulting from unintended pregnancies: national and state-level estimates. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011 Jun;43(2):94–102. doi: 10.1363/4309411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavin L, Moskosky S, Carter M, Curtis K, Glass E, Godfrey E, Marcell A, Mautone-Smith N, Pazol K, Tepper N, Zapata L, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Providing quality family planning services: recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014 Apr 25;63(RR-04):1–54. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6304a1.htm .rr6304a1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gavin L, Frederiksen B, Robbins C, Pazol K, Moskosky S. New clinical performance measures for contraceptive care: their importance to healthcare quality. Contraception. 2017 Sep;96(3):149–57. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.05.013.S0010-7824(17)30158-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boghossian NS, Yeung E, Albert PS, Mendola P, Laughon SK, Hinkle SN, Zhang C. Changes in diabetes status between pregnancies and impact on subsequent newborn outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 May;210(5):431.e1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.12.026. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24361790 .S0002-9378(13)02237-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiely M, El-Mohandes AA, Gantz MG, Chowdhury D, Thornberry JS, El-Khorazaty MN. Understanding the association of biomedical, psychosocial and behavioral risks with adverse pregnancy outcomes among African-Americans in Washington, DC. Matern Child Health J. 2011 Dec;15(Suppl 1):S85–95. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0856-z. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/21785892 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy VE, Clifton VL, Gibson PG. Asthma exacerbations during pregnancy: incidence and association with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Thorax. 2006 Feb;61(2):169–76. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.049718. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/16443708 .61/2/169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alves E, Azevedo A, Rodrigues T, Santos AC, Barros H. Impact of risk factors on hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, in primiparae and multiparae. Ann Hum Biol. 2013;40(5):377–84. doi: 10.3109/03014460.2013.793390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berg CJ, Harper MA, Atkinson SM, Bell EA, Brown HL, Hage ML, Mitra AG, Moise KJ, Callaghan WM. Preventability of pregnancy-related deaths: results of a state-wide review. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Dec;106(6):1228–34. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000187894.71913.e8.106/6/1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berg CJ, Mackay AP, Qin C, Callaghan WM. Overview of maternal morbidity during hospitalization for labor and delivery in the United States: 1993-1997 and 2001-2005. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 May;113(5):1075–81. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a09fc0.00006250-200905000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayes DK, Fan AZ, Smith RA, Bombard JM. Trends in selected chronic conditions and behavioral risk factors among women of reproductive age, behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2001-2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011 Nov;8(6):A120. https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2011/nov/10_0083.htm .A120 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farr SL, Hayes DK, Bitsko RH, Bansil P, Dietz PM. Depression, diabetes, and chronic disease risk factors among US women of reproductive age. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011 Nov;8(6):A119. https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2011/nov/10_0269.htm .A119 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ward BW, Schiller JS. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among US adults: estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013 Apr 25;10:E65. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120203. https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2013/12_0203.htm .E65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chor J, Rankin K, Harwood B, Handler A. Unintended pregnancy and postpartum contraceptive use in women with and without chronic medical disease who experienced a live birth. Contraception. 2011 Jul;84(1):57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.11.018.S0010-7824(10)00690-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gawron LM, Gawron AJ, Kasper A, Hammond C, Keefer L. Contraceptive method selection by women with inflammatory bowel diseases: a cross-sectional survey. Contraception. 2014 May;89(5):419–25. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.12.016. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24486008 .S0010-7824(14)00007-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maslow BL, Morse CB, Schanne A, Loren A, Domchek SM, Gracia CR. Contraceptive use and the role of contraceptive counseling in reproductive-aged women with cancer. Contraception. 2014 Jul;90(1):79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.03.002.S0010-7824(14)00100-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwarz EB, Postlethwaite D, Hung Y, Lantzman E, Armstrong MA, Horberg MA. Provision of contraceptive services to women with diabetes mellitus. J Gen Intern Med. 2012 Feb;27(2):196–201. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1875-6. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/21922154 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwarz EB, Braughton MY, Riedel JC, Cohen S, Logan J, Howell M, Thiel de Bocanegra H. Postpartum care and contraception provided to women with gestational and preconception diabetes in California's Medicaid program. Contraception. 2017 Aug 24;96(6):432–38. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.08.006.S0010-7824(17)30402-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwarz EB, Maselli J, Norton M, Gonzales R. Prescription of teratogenic medications in United States ambulatory practices. Am J Med. 2005 Nov;118(11):1240–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.02.029.S0002-9343(05)00195-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisenberg DL, Stika C, Desai A, Baker D, Yost KJ. Providing contraception for women taking potentially teratogenic medications: a survey of internal medicine physicians' knowledge, attitudes and barriers. J Gen Intern Med. 2010 Apr;25(4):291–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1215-2. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20087677 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control [2018-01-30]. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2010 Summary Tables https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2010_namcs_web_tables.pdf .

- 25.Ornstein SM, Jenkins RG, Litvin CB, Wessell AM, Nietert PJ. Preventive services delivery in patients with chronic illnesses: parallel opportunities rather than competing obligations. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(4):344–9. doi: 10.1370/afm.1502. http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=23835820 .11/4/344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akers AY, Gold MA, Borrero S, Santucci A, Schwarz EB. Providers' perspectives on challenges to contraceptive counseling in primary care settings. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010 Jun;19(6):1163–70. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1735. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20420508 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dehlendorf C, Levy K, Ruskin R, Steinauer J. Health care providers' knowledge about contraceptive evidence: a barrier to quality family planning care? Contraception. 2010 Apr;81(4):292–8. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.11.006. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20227544 .S0010-7824(09)00490-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russo JA, Chen BA, Creinin MD. Primary care physician familiarity with U.S. medical eligibility for contraceptive use. Fam Med. 2015 Jan;47(1):15–21. http://www.stfm.org/FamilyMedicine/Vol47Issue1/Russo15 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Marchbanks PA. Putting risk into perspective: the US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2011 Jun;12(2):119–25. doi: 10.1007/s11154-011-9177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee opinion no. 505: understanding and using the U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria For Contraceptive Use, 2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Sep;118(3):754–60. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182310cd3.00006250-201109000-00044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biggs MA, Harper CC, Malvin J, Brindis CD. Factors influencing the provision of long-acting reversible contraception in California. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Mar;123(3):593–602. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harper CC, Henderson JT, Raine TR, Goodman S, Darney PD, Thompson KM, Dehlendorf C, Speidel JJ. Evidence-based IUD practice: family physicians and obstetrician-gynecologists. Fam Med. 2012 Oct;44(9):637–45. http://www.stfm.org/fmhub/fm2012/October/Cynthia637.pdf . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubin SE, Fletcher J, Stein T, Segall-Gutierrez P, Gold M. Determinants of intrauterine contraception provision among US family physicians: a national survey of knowledge, attitudes and practice. Contraception. 2011 May;83(5):472–8. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.10.003.S0010-7824(10)00596-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu JP, Gundersen DA, Pickle S. Are the contraceptive recommendations of family medicine educators evidence-based? A CERA survey. Fam Med. 2016 Dec;48(5):345–52. http://www.stfm.org/FamilyMedicine/Vol48Issue5/Wu345 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 121: Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Jul;118(1):184–96. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318227f05e.00006250-201107000-00031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson AL. Intrauterine device practice guidelines: medical conditions. Contraception. 1998 Sep;58(3 Suppl):59S–63S; quiz 72S. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(98)00084-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suri V, Aggarwal N, Kaur R, Chaudhary N, Ray P, Grover A. Safety of intrauterine contraceptive device (copper T 200 B) in women with cardiac disease. Contraception. 2008 Oct;78(4):315–8. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.05.006.S0010-7824(08)00327-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bitzer J, Cupanik V, Fait T, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Grob P, Oddens BJ, Pawelczyk L, Unzeitig V. Factors influencing women's selection of combined hormonal contraceptive methods after counselling in 11 countries: results from a subanalysis of the CHOICE study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2013 Oct;18(5):372–80. doi: 10.3109/13625187.2013.819077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harper CC, Brown BA, Foster-Rosales A, Raine TR. Hormonal contraceptive method choice among young, low-income women: how important is the provider? Patient Educ Couns. 2010 Dec;81(3):349–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.08.010. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20837389 .S0738-3991(10)00531-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenberg MJ, Waugh MS, Burnhill MS. Compliance, counseling and satisfaction with oral contraceptives: a prospective evaluation. Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30(2):89–92, 104. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/3008998.html . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dehlendorf C, Levy K, Kelley A, Grumbach K, Steinauer J. Women's preferences for contraceptive counseling and decision making. Contraception. 2013 Aug;88(2):250–6. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.10.012. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/23177265 .S0010-7824(12)00901-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Langston AM, Rosario L, Westhoff CL. Structured contraceptive counseling--a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2010 Dec;81(3):362–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.08.006.S0738-3991(10)00527-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melo J, Peters M, Teal S, Guiahi M. Adolescent and young women's contraceptive decision-making processes: choosing “The Best Method for Her”. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015 Aug;28(4):224–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2014.08.001.S1083-3188(14)00270-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Donnelly KZ, Foster TC, Thompson R. What matters most? The content and concordance of patients' and providers' information priorities for contraceptive decision making. Contraception. 2014 Sep;90(3):280–7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.04.012.S0010-7824(14)00197-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.George TP, DeCristofaro C, Dumas BP, Murphy PF. Shared decision aids: increasing patient acceptance of long-acting reversible contraception. Healthcare (Basel) 2015 Apr 10;3(2):205–18. doi: 10.3390/healthcare3020205. http://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=healthcare3020205 .healthcare3020205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marshall C, Nuru-Jeter A, Guendelman S, Mauldon J, Raine-Bennett T. Patient perceptions of a decision support tool to assist with young women's contraceptive choice. Patient Educ Couns. 2017 Feb;100(2):343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.08.022.S0738-3991(16)30373-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.French RS, Wellings K, Cowan FM. How can we help people to choose a method of contraception? The case for contraceptive decision aids. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2009 Oct;35(4):219–20. doi: 10.1783/147118909789587169. http://jfprhc.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=19849914 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alston C, Berger Z, Brownlee S, Elwyn G, Fowler FJ, Hall LK, Montori V, Moulton B, Paget L, Shebel B, Singerman R, Walker J, Wynia M, Henderson D. Washington, DC: Discussion Paper, Institute of Medicine; [2017-11-30]. Shared decision-making strategies for best care: Patient decision aids https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/SDMforBestCare2.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dehlendorf C, Grumbach K, Schmittdiel JA, Steinauer J. Shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Contraception. 2017 May;95(5):452–455. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.12.010.S0010-7824(17)30002-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim YM, Kols A, Martin A, Silva D, Rinehart W, Prammawat S, Johnson S, Church K. Promoting informed choice: evaluating a decision-making tool for family planning clients and providers in Mexico. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2005 Dec;31(4):162–71. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.31.162.05. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/3116205.html .3116205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chewning B, Mosena P, Wilson D, Erdman H, Potthoff S, Murphy A, Kuhnen KK. Evaluation of a computerized contraceptive decision aid for adolescent patients. Patient Educ Couns. 1999 Nov;38(3):227–39. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00014-2.S0738399199000142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garbers S, Meserve A, Kottke M, Hatcher R, Ventura A, Chiasson MA. Randomized controlled trial of a computer-based module to improve contraceptive method choice. Contraception. 2012 Oct;86(4):383–90. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.01.013.S0010-7824(12)00044-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marshall C, Nuru-Jeter A, Guendelman S, Mauldon J, Raine-Bennett T. Patient perceptions of a decision support tool to assist with young women's contraceptive choice. Patient Educ Couns. 2017 Feb;100(2):343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.08.022.S0738-3991(16)30373-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dehlendorf C, Fitzpatrick J, Steinauer J, Swiader L, Grumbach K, Hall C, Kuppermann M. Development and field testing of a decision support tool to facilitate shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Patient Educ Couns. 2017 Jul;100(7):1374–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.02.009.S0738-3991(17)30073-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 1999. Using codes and code manuals; pp. 163–178. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fetters MD, Freshwaters D. The 1+ 1= 3 Integration Challenge. J Mix Methods Res. 2015;9(2):115–117. doi: 10.1177/1558689815581222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Creswell J, Plano Clark VL. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015 Apr 21;10:53. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0. https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0 .10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. http://www.implementationscience.com/content/4//50 .1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res. 2013 Dec;48(6 Pt 2):2134–56. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12117. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24279835 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Onwuegbuzie AJ, Leech NL. Validity and qualitative research: An oxymoron? Qual Quant. 2007;41:233–49. doi: 10.1007/s11135-006-9000-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015 Sep;42(5):533–44. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24193818 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen M, Culwell K. The Global Library of Women's Medicine. [2017-12-15]. Contraception for women with medical problems https://www.glowm.com/section_view/heading/Contraception%20for%20Women%20With%20Medical%20Problems/item/381 .

- 64.Borrero S, Schwarz EB, Creinin M, Ibrahim S. The impact of race and ethnicity on receipt of family planning services in the United States. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18(1):91–6. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.0976. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19072728 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [2017-12-01]. Practice-Based Research Networks https://pbrn.ahrq.gov .

- 66.Creswell JW. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 2015. Sampling and integration issues; pp. 105–120. [Google Scholar]

- 67.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Washington, D.C: 2015. [2017-10-17]. Multiple chronic conditions: a strategic framework. Optimum health quality of life for individuals with multiple chronic conditions https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ash/initiatives/mcc/mcc_framework.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ornstein SM, Nietert PJ, Jenkins RG, Litvin CB. The prevalence of chronic diseases and multimorbidity in primary care practice: a PPRNet report. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(5):518–24. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2013.05.130012. http://www.jabfm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=24004703 .26/5/518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention United States Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC) for Contraceptive Use 2016 https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/mmwr/mec/summary.html .

- 70.Dehlendorf C, Fitzpatrick J, Steinauer J, Swiader L, Grumbach K, Hall C, Kuppermann M. Development and field testing of a decision support tool to facilitate shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Patient Educ Couns. 2017 Jul;100(7):1374–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.02.009.S0738-3991(17)30073-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, O'Connor D, Patey A, Ivers N, Foy R, Duncan EM, Colquhoun H, Grimshaw JM, Lawton R, Michie S. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci. 2017 Jun 21;12(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9. https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9 .10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wyatt KD, Anderson RT, Creedon D, Montori VM, Bachman J, Erwin P, LeBlanc A. Women's values in contraceptive choice: a systematic review of relevant attributes included in decision aids. BMC Womens Health. 2014 Feb 13;14(1):28. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-28. https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-6874-14-28 .1472-6874-14-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Madden T, Secura GM, Nease RF, Politi MC, Peipert JF. The role of contraceptive attributes in women's contraceptive decision making. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jul;213(1):46.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.01.051. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25644443 .S0002-9378(15)00107-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ross L. Understanding reproductive justice: Transforming the pro-choice movement. 2006;36:14–19. doi: 10.2307/20838711. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/rrfp/pages/33/attachments/original/1456425809/Understanding_RJ_Sistersong.pdf?1456425809 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stern AM. Eugenics, sterilization, and historical memory in the United States. Hist Cienc Saude Manguinhos. 2016 Dec;23Suppl 1(Suppl 1):195–212. doi: 10.1590/S0104-59702016000500011. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104-59702016000900195&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en .S0104-59702016000900195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stern AM. Sterilized in the name of public health: race, immigration, and reproductive control in modern California. Am J Public Health. 2005 Jul;95(7):1128–38. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.041608.95/7/1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Witteman HO, Scherer LD, Gavaruzzi T, Pieterse AH, Fuhrel-Forbis A, Chipenda DS, Exe N, Kahn VC, Feldman-Stewart D, Col NF, Turgeon AF, Fagerlin A. Design features of explicit values clarification methods: a systematic review. Med Decis Making. 2016 May;36(4):453–71. doi: 10.1177/0272989X15626397.0272989X15626397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Prochaska JO. Decision making in the transtheoretical model of behavior change. Med Decis Making. 2008;28(6):845–9. doi: 10.1177/0272989X08327068.0272989X08327068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hall KS. The Health Belief Model can guide modern contraceptive behavior research and practice. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2012;57(1):74–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00110.x. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22251916 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Stange KC. Understanding practice from the ground up. J Fam Pract. 2001 Oct;50(10):881–7.jfp_1001_08810 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jaén CR, Crabtree BF, Palmer RF, Ferrer RL, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Stewart EE, Wood R, Davila M, Stange KC. Methods for evaluating practice change toward a patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8 Suppl 1:S9–20; S92. doi: 10.1370/afm.1108. http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=20530398 .8/Suppl_1/S9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Goldblatt H, Karnieli-Miller O, Neumann M. Sharing qualitative research findings with participants: study experiences of methodological and ethical dilemmas. Patient Educ Couns. 2011 Mar;82(3):389–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.12.016.S0738-3991(10)00788-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Borkan J. Immersion/Crystallization. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing Qualitative Research. 2 edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2009. pp. 179–94. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Creswell J, Clark V. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2011. Analyzing and interpreting data in mixed methods research; pp. 203–250. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marshall C, Rossman G. Designing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 2016. Managing, analyzing, and interpreting data. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Using codes and code manuals: a template organizing style of interpretation. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing Qualitative Research. 2 edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Qualitative sampling matrix.

Mixed methods theory data matrix: mapping data to Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) inner setting constructs.

Mixed methods theory data matrix: mapping data to Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) outer setting and intervention constructs.

Mixed methods theory data matrix: mapping data to Theoretical Domains Framework (TDR) constructs.