Abstract

Background

Brexpiprazole is a serotonin–dopamine activity modulator with efficacy in acute schizophrenia and relapse prevention. The aim of this Phase 3, multicenter study was to assess the long-term safety, tolerability, and efficacy of treatment with brexpiprazole flexible-dose 1–4 mg/d.

Methods

Patients rolled over into this 52-week open-label study (amended to 26 weeks towards the end) from 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 3 studies. De novo patients, not part of the previous studies, were also enrolled. The primary outcome variable was the frequency and severity of treatment-emergent adverse events. Efficacy was assessed as a secondary objective using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale and the Personal and Social Performance scale.

Results

A total of 1072 patients was enrolled (952 for 52 weeks and 120 for 26 weeks), 47.4% of whom completed the study. Among patients who took at least one dose of brexpiprazole, 14.6% discontinued due to treatment-emergent adverse events, most commonly schizophrenia (8.8%) and psychotic disorder (1.5%). Treatment-emergent adverse events with an incidence of ≥5% were schizophrenia (11.6%), insomnia (8.6%), weight increased (7.8%), headache (6.4%), and agitation (5.4%). Most treatment-emergent adverse events were mild or moderate in severity. The mean increase in body weight from baseline to week 26 was 1.3 kg and to week 52 was 2.1 kg. There were no clinically relevant findings related to prolactin, lipids, and glucose, or QT prolongation. On average, patients’ symptoms and functioning showed continual improvement.

Conclusions

Treatment with brexpiprazole 1–4 mg/d was generally well tolerated for up to 52 weeks in patients with schizophrenia.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier

Keywords: brexpiprazole, long-term, open-label, schizophrenia

Significance Statement

Brexpiprazole is an antipsychotic that has shown a clinically meaningful benefit for the acute treatment of schizophrenia in 2 placebo-controlled clinical studies. A further, long-term study showed that brexpiprazole maintenance therapy reduced the risk of relapse vs placebo over the course of a year. The study described in this paper is an extension of these 3 studies, which was designed primarily to assess the long-term safety and tolerability of brexpiprazole treatment. The study also enrolled patients who had not previously been in a brexpiprazole study. For up to 1 year, patients received open-label brexpiprazole that was flexibly dosed in the range of 1–4 mg/d. No unexpected safety or tolerability issues emerged, and the safety profile was consistent with the previous brexpiprazole studies in schizophrenia. Overall, this study adds to the evidence-base demonstrating that brexpiprazole is a generally well-tolerated antipsychotic in the long-term.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a chronic illness, associated with considerable disability and requiring lifelong treatment. Current antipsychotics are generally efficacious in treating the acute symptoms of schizophrenia, with small differences in efficacy between agents (Leucht et al., 2013). Antipsychotics as a group are also efficacious for the prevention of relapse in the long term (Leucht et al., 2012). However, individual patient response to a particular agent is highly heterogeneous (Citrome, 2013). Furthermore, the symptoms and disease course of schizophrenia vary greatly between patients, and antipsychotics are not able to manage the broad spectrum of symptoms in all patients (Lecrubier et al., 2007; Owen et al., 2016). Current antipsychotics show considerable differences in their propensity towards adverse events (Leucht et al., 2013; Citrome, 2017). Patient preference, based on concerns about specific adverse effects, is another factor that can influence the choice of an antipsychotic treatment (Citrome, 2013). Consequently, selection of a specific antipsychotic medication for the treatment of schizophrenia is an individualized risk–benefit decision based on short- and long-term issues, including the relative clinical efficacy, safety, and tolerability of available antipsychotics (Lehman et al., 2004). Finding an antipsychotic that works “well enough” and is tolerated “well enough” for an individual patient is a substantial challenge in the day-to-day clinical management of individuals with schizophrenia (Citrome, 2012).

Brexpiprazole is a serotonin–dopamine activity modulator that acts as a partial agonist at serotonin 5-HT1A and dopamine D2 receptors, and as an antagonist at serotonin 5-HT2A and noradrenaline α1B/2C receptors, all with similar, subnanomolar potency (Maeda et al., 2014). Brexpiprazole has a low potential to induce D2 agonist-mediated adverse effects and D2 antagonist-like adverse effects (Maeda et al., 2014). Relative to its D2/5-HT1A receptor affinity, brexpiprazole has a moderate/low affinity for histamine H1 receptors (Maeda et al., 2014), which may limit the risk for sedation and weight gain (Nasrallah, 2008). The efficacy and safety of brexpiprazole have been demonstrated in a Phase 3 schizophrenia program comprising two 6-week, fixed-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies, and a 52-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, relapse-prevention study with a withdrawal design (Correll et al., 2015; Kane et al., 2015; Fleischhacker et al., 2017). Brexpiprazole is approved in the US, Canada, and Australia for the treatment of schizophrenia in adults, and also in the US as an adjunctive therapy to antidepressants for the treatment of major depressive disorder in adults.

Long-term maintenance treatment is recommended to control the symptoms of schizophrenia (Lehman et al., 2004; Hasan et al., 2013); therefore, safety monitoring for longer than the period required to treat an acute exacerbation is warranted. The aim of the present study was to assess the long-term safety and tolerability of open-label treatment with brexpiprazole (flexible dose 1–4 mg/d) in patients with schizophrenia. The long-term efficacy of brexpiprazole treatment was also assessed.

Methods

Patients

Patients were recruited at 202 sites across 18 countries in Asia (Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, Taiwan), Europe (Croatia, Latvia, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Turkey, Ukraine), Latin America (Colombia, Mexico), and North America (Canada, Puerto Rico, United States). The study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice Consolidated Guideline, and local regulatory requirements, and the protocol was approved by the governing institutional review board or independent ethics committee for each investigational site or country, as appropriate. All patients provided written informed consent prior to the start of the study.

Patients rolled over from 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 3 studies of brexpiprazole in schizophrenia (Vector, NCT01396421; Beacon, NCT01393613; and Equator, NCT01668797). In addition, new (de novo) patients were enrolled who had not previously participated in a brexpiprazole clinical study. Vector and Beacon were acute 6-week studies (Correll et al., 2015; Kane et al., 2015), whereas Equator was a relapse-prevention study comprising a 12- to 36-week stabilization phase and a maintenance phase of up to 52 weeks (Fleischhacker et al., 2017). Equator was terminated early following demonstration of efficacy vs placebo at a prespecified interim analysis (Fleischhacker et al., 2017).

The present open-label study included male and female outpatients (or inpatients from Equator) aged 18 to 65 years who, in the investigator’s judgment, could potentially benefit from monotherapy treatment with oral brexpiprazole. Rollover patients were required to have completed their respective studies (in addition, patients could be rolled over from Equator if they had withdrawn from the maintenance phase of the study due to impending relapse). De novo patients were required to have a diagnosis of schizophrenia for at least 3 years as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000); to be currently treated with an oral antipsychotic (other than clozapine) or to have a recent lapse in antipsychotic treatment; to have been stable on an antipsychotic regimen for at least one 3-month period in the last year; and, in the investigator’s judgment, to be in need of chronic treatment with antipsychotic medication. Exclusion criteria included a positive pregnancy test or currently breastfeeding; a DSM-IV-TR Axis I diagnosis other than schizophrenia; acute depressive symptoms in the previous 30 days requiring antidepressant therapy; antipsychotic-resistant or refractory schizophrenia; a significant risk of violent behavior or suicide; meeting DSM-IV-TR criteria for substance abuse or dependence in the previous 180 days; a clinically significant neurological, hepatic, renal, metabolic, hematological, immunological, cardiovascular, pulmonary, or gastrointestinal disorder; or requiring prohibited concomitant therapy during the study.

Study Design

This was a Phase 3, multicenter, open-label study, conducted from 15 September, 2011 to 25 February, 2016. The study comprised a screening process, an as-needed phase for converting de novo patients from baseline antipsychotics to brexpiprazole, and a 52-week open-label brexpiprazole treatment phase.

Rollover patients were screened for eligibility at the last visit of their respective Phase 3 study (week 6 for Vector and Beacon; week 52 or the time of withdrawal for Equator). Eligible patients entered the 52-week brexpiprazole treatment phase directly.

De novo patients underwent a 2- to 28-day screening process to assess eligibility and to washout from prohibited concomitant medications, if applicable. Eligible patients entered the 52-week brexpiprazole treatment phase directly if they had not taken an antipsychotic within 7 days; otherwise, they entered a conversion phase. In the conversion phase (weekly visits), de novo patients were cross-titrated to oral brexpiprazole 2 mg/d over a period of 4 weeks, as follows: days 0–13, brexpiprazole 1 mg/d (no change in concurrent baseline antipsychotic); days 14–20, brexpiprazole 1 or 2 mg/d (baseline antipsychotic decreased); days 21–27, brexpiprazole 2 mg/d (baseline antipsychotic decreased); day 28, brexpiprazole 2 mg/d (baseline antipsychotic discontinued).

In the 52-week open-label treatment phase (visits at weeks 1, 2, 4, and 8, then at 6-weekly intervals), all patients began with oral brexpiprazole 2 mg/d (or 1–4 mg/d for patients from Equator, based on their last dose). Doses could be adjusted within the range of 1–4 mg/d, in 1-mg increments, for reasons of efficacy or tolerability, according to the investigator’s judgement.

Safety follow-up comprised telephone contact or a clinic visit 30 (+2) days after the last dose.

Two amendments were made to the protocol after the study had started. The first, following the early termination of Equator, was to allow the entry of patients who were withdrawn from Equator (any phase) at the time of early termination. The second was a reduction of the study duration from 52 to 26 weeks for all patients who enrolled after the date of the amendment. The reason for this amendment was that the safety profile of brexpiprazole was considered to be well established in the completed double-blind and long-term studies, together with the population in this study.

Assessments

The primary objective of the study was to assess the long-term safety and tolerability of oral brexpiprazole as monotherapy in adults with schizophrenia. Safety was assessed by spontaneous reporting of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs; primary outcome), clinical laboratory tests, physical examination, vital signs, body mass index, and ECGs. Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) were formally assessed using the Simpson–Angus Scale (Simpson & Angus, 1970), Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (Barnes, 1989), and Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (Guy, 1976). Suicidality was assessed using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (Posner et al., 2011).

The secondary objective of the study was to assess the long-term efficacy of oral brexpiprazole as monotherapy in adults with schizophrenia. Efficacy was assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay et al., 1987), Clinical Global Impressions – Severity of illness (CGI-S) and Improvement (CGI-I) scales (Guy, 1976), and the Personal and Social Performance scale (PSP; a measure of social functioning and behavior; Morosini et al., 2000). The PANSS, CGI-S, and CGI-I were administered at each visit; the PSP was administered at weeks 2, 8, 26, and 52. The efficacy outcomes were the mean change from baseline to each visit in PANSS Total score, Positive and Negative subscale scores, Excited component score (a measure of aggression/agitation; Montoya et al., 2011), and all 5 Marder factor scores (positive symptoms, negative symptoms, disorganized thought, uncontrolled hostility/excitement, and anxiety/depression; Marder et al., 1997); the mean change in CGI-S score; the mean CGI-I score; the mean change in PSP Total score; the response rate (defined as a reduction of ≥30% from baseline in PANSS Total score, or a CGI-I score of 1 [very much improved] or 2 [much improved]); and the discontinuation rate due to lack of efficacy.

Information regarding the extent of medical care sought by patients while participating in the study was collected using a resource utilization form.

Statistical Analyses

The sample size was determined by the number of eligible rollover patients, plus approximately 200 de novo patients, rather than by statistical power considerations.

The enrolled population comprised all patients who enrolled in either the conversion phase or the open-label treatment phase. The safety population comprised all patients who received at least one dose of brexpiprazole in the open-label treatment phase. The efficacy population comprised all patients in the safety population who had at least 1 post-baseline efficacy evaluation on the PANSS in the open-label treatment phase.

The primary outcome variable was the frequency and severity of TEAEs in the open-label treatment phase. All safety variables were presented using descriptive statistics for the safety population. Efficacy variables were presented using descriptive statistics for the efficacy population, using observed cases at each visit. PANSS Total, CGI-S, and PSP Total outcomes were also stratified by the treatment received prior to rollover (i.e., prior brexpiprazole, prior placebo, or de novo).

Baseline was defined as the last available measurement prior to the first dose of brexpiprazole in the open-label treatment phase.

Results

Patients

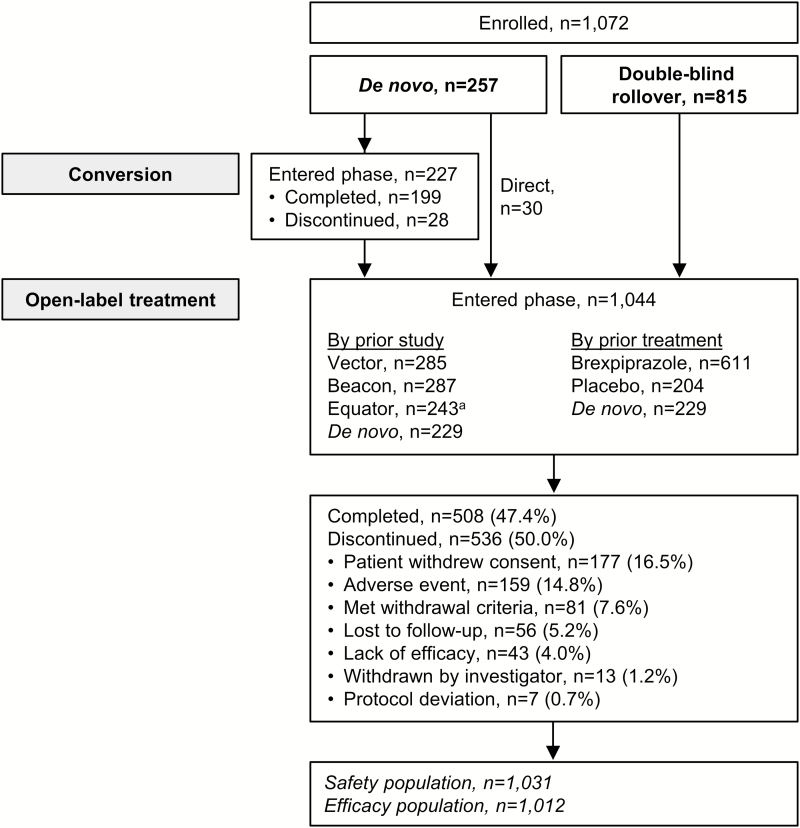

A total of 1072 patients were enrolled in the study, either into the conversion phase or directly into the open-label treatment phase. Of these patients, 952 were enrolled for 52 weeks (i.e., they were enrolled before the amendment that reduced the study duration from 52 to 26 weeks), and 120 were enrolled for 26 weeks (i.e., after the amendment). Twenty-eight patients discontinued during the conversion phase, and a total of 1044 patients entered the open-label treatment phase (rollover n=815; de novo n=229) (Figure 1). Of the 815 rollover patients, 611 had previously received brexpiprazole and 204 had previously received placebo.

Figure 1.

Patient disposition and reasons for discontinuation. aTwelve patients rolled over from Equator before being fully converted to brexpiprazole (due to the study’s early termination). To align with the Equator protocol, these patients were cross-titrated to brexpiprazole 1–4 mg/d for a total of 4 weeks, according to the investigator’s judgement, before entering the open-label treatment phase.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. On average, the patients were mild-to-moderately ill at baseline, with a mean PANSS Total score of 69.5 and a mean CGI-S score of 3.5. The mean PSP Total score was 58.5, indicating that the patients had marked or severe difficulties in several areas of functioning.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Demographic Characteristics | Enrolled Population (n=1072) |

|---|---|

| Age (y), mean (SD) | 40.0 (11.1) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 27.9 (6.6) |

| Female, n (%) | 409 (38.2) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 665 (62.0) |

| Black/African American | 267 (24.9) |

| Asian | 63 (5.9) |

| Other | 77 (7.2) |

| Clinical Characteristics | Safety Population (n=1031) |

| PANSS Total score, mean (SD) | 69.5 (17.2) |

| CGI-S score, mean (SD) | 3.5 (0.9) |

| PSP Total score, mean (SD) | 58.5 (12.8)a |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions – severity of illness; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PSP, Personal and Social Performance scale.

an=1015.

Overall, 508 patients completed the study (either 52 weeks or 26 weeks [the study was completed by 43.0% (409/952) of patients who enrolled for 52 weeks, and 82.5% (99/120) of patients who enrolled for 26 weeks]; 47.4% of enrolled patients), and 617 patients had at least 26 weeks of observations (57.6%). The most common reasons for discontinuation in the open-label treatment phase were withdrawal of consent (16.5%) and TEAEs (14.8%) (Figure 1). The mean daily dose of brexpiprazole at last visit was 3.0 mg (n=1031).

Safety

The proportion of patients who experienced at least one TEAE during the open-label brexpiprazole treatment phase was 60.4%. The most frequently reported TEAE was worsening of schizophrenia (11.6%). TEAEs with an incidence of ≥5% were worsening of schizophrenia, insomnia, weight increased, headache, and agitation (Table 2). The most frequently reported EPS-related TEAE was akathisia (4.8%). There were 2 cases of seizure during the study: one was mild, nonserious, possibly related to brexpiprazole, and resulted in discontinuation; the other was severe, serious, and considered not related to brexpiprazole. Most TEAEs were mild or moderate in severity; 82 patients (8.0%) experienced a severe TEAE. The proportion of patients who discontinued the study due to adverse events during the open-label brexpiprazole treatment phase was 14.6%. TEAEs associated with discontinuation in ≥1.0% of patients were worsening of schizophrenia (n=91; 8.8%) and worsening of psychotic disorder (n=15; 1.5%).

Table 2.

Summary of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events (TEAEs) Over 52 Weeks for Patients With Schizophrenia Receiving Open-Label Brexpiprazole 1–4 mg/d

| Safety Population (n=1031), n (%) | |

|---|---|

| At least one TEAE | 623 (60.4) |

| Discontinuation due to TEAE | 151 (14.6) |

| TEAEs occurring in ≥5% of patients | |

| Schizophrenia | 120 (11.6) |

| Insomnia | 89 (8.6) |

| Weight increased | 80 (7.8) |

| Headache | 66 (6.4) |

| Agitation | 56 (5.4) |

| Other relevant TEAEs | |

| Akathisia | 49 (4.8) |

| Anxiety | 23 (2.2) |

| Somnolence | 22 (2.1) |

| Restlessness | 9 (0.9) |

| Sedation | 9 (0.9) |

| Fatigue | 7 (0.7) |

| Hypersomnia | 1 (0.1) |

The mean increase in body weight from baseline to week 26 was 1.3 kg (n=611), and from baseline to week 52 was 2.1 kg (n=408). The incidence of an increase in body weight of ≥7% at any post-baseline visit was 18.6%, and the incidence of a decrease in body weight of ≥7% at any post-baseline visit was 9.2% (supplementary Table 1).

There were no clinically relevant findings for events related to prolactin, lipids and glucose, or QT prolongation, including the incidence of shifts to abnormal levels, presented in supplementary Table 1. The proportion of patients meeting the criteria for treatment-emergent metabolic syndrome (i.e., 3 or more of central obesity, dyslipidemia, increased blood pressure, and increased fasting serum glucose levels) at any visit was 3.8% (29 of 761 patients who did not meet the criteria at baseline and who had a post-baseline measurement). The mean prolactin level change from baseline to week 26 was 2.5 ng/mL in females (n=242) and 0.0 ng/mL in males (n=361), and from baseline to week 52 was -0.1 ng/mL in females (n=159) and 0.7 ng/mL in males (n=240). Three patients (0.3%) in the open-label treatment phase reported hyperprolactinemia as a TEAE. The mean change in fasting glucose from baseline to week 26 was 2.3 mg/dL (n=549) and from baseline to week 52 was 2.7 mg/dL (n=369).

No clinically meaningful changes were observed on formal EPS rating scales (supplementary Table 2). Overall, 9.5% (98/1031) of patients had an EPS-related TEAE during the open-label treatment phase. One patient, in the de novo subgroup, experienced tardive dyskinesia. The event started on day 393 of the study and was considered moderately severe, nonserious, and possibly related to brexpiprazole.

During the open-label treatment phase, suicidal ideation emerged in 3.6% of patients, and suicidal behavior emerged in 0.2% of patients. Suicidal ideation as a TEAE occurred in 0.6% of patients. Six patients died during the study, including one completed suicide; all were considered by the investigator to be unrelated to brexpiprazole treatment. One patient took an overdose of 27 tablets (54 mg) of brexpiprazole in response to a serious TEAE of command auditory hallucinations; the patient denied any suicidal intent. The patient was discontinued from the study and did not experience any after effects due to the overdose.

Women of childbearing potential were required to use 2 forms of birth control during the study; however, 1 patient became pregnant having received open-label brexpiprazole for 278 days. The patient was discontinued from the study (last dose: 4 mg on 26 August, 2013) and had a normal baby on 5 April, 2014 with a weight of 2.8 kg and Apgar scores of 9 at 1 and 5 minutes.

Efficacy

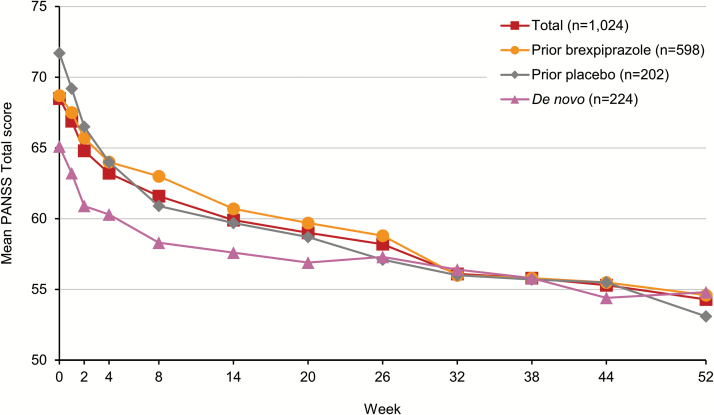

Long-term brexpiprazole treatment was associated with improvement in all efficacy measures and functional outcomes during the open-label brexpiprazole treatment phase (Table 3). Mean (SD) PANSS Total score improved by 12.2 (15.0) points from baseline to week 52 (Figure 2). Patients improved irrespective of whether they had previously been treated with brexpiprazole or placebo, or were de novo. Although patients who had previously received placebo had a higher baseline PANSS Total score (71.7) than those who had previously received brexpiprazole (68.7), by 52 weeks these 2 subgroups had converged. De novo patients had the lowest baseline PANSS Total score of the 3 prior treatment subgroups (65.1). The majority of these patients (n=199/229; 86.9%) entered via the 4-week conversion phase and had already improved by a mean (SD) of 4.0 (9.5) points with brexpiprazole treatment between the start of the conversion phase and the baseline of the open-label phase. After 52 weeks of open-label brexpiprazole treatment, the de novo patient subgroup also converged with the subgroups of patients who had received prior brexpiprazole or placebo. In addition to benefits on PANSS Total score, open-label brexpiprazole treatment was associated with improvement in PANSS Positive and Negative subscale scores, Excited component score, and all 5 Marder factor scores (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of Efficacy Endpoints Over 52 Weeks for Patients with Schizophrenia Receiving Open-Label Brexpiprazole 1–4 mg/d (Observed Cases)

| Mean (SD) at Baseline (n=1024) | Mean (SD) Change from Baseline to Week 52 (n=410) | |

|---|---|---|

| PANSS Total score | 68.5 (17.1) | -12.2 (15.0) |

| PANSS Positive subscale score | 16.3 (5.4) | -3.6 (4.8) |

| PANSS Negative subscale score | 19.0 (5.3) | -2.8 (4.6) |

| PANSS Excited component score | 8.6 (3.3) | -1.5 (3.2) |

| PANSS Marder factor scores | ||

| Positive symptoms | 20.2 (6.1) | -4.2 (5.4) |

| Negative symptoms | 17.6 (5.4) | -2.8 (4.4) |

| Disorganized thought | 16.7 (4.9) | -2.9 (4.0) |

| Uncontrolled hostility/excitement | 6.6 (2.8) | -1.1 (2.7) |

| Anxiety/depression | 7.3 (3.0) | -1.2 (2.9) |

| CGI-S score | 3.5 (0.9) | -0.6 (0.9) |

| CGI-I score | NA | 2.6 (1.1)a |

| PSP Total score | 58.8 (12.8)b | 7.7 (11.0)c |

| Response rated | NA | 354/1031 (34.3)e |

| Discontinuation rate due to lack of efficacy | NA | 43/1031 (4.2)e |

Abbreviations: CGI-I, Clinical Global Impressions – Improvement; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions – Severity of illness; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PSP, Personal and Social Performance scale.

aMean (SD) at week 52.

bn=1015.

cn=407.

dResponse defined as a reduction of ≥30% from baseline in PANSS Total score, or a CGI-I score of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved).

eNumber of patients who met criteria/total number of patients who received a dose of brexpiprazole in the open-label treatment phase (%).

Figure 2.

Mean Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) Total score over 52 weeks for patients with schizophrenia receiving open-label brexpiprazole 1–4 mg/d, stratified by treatment prior to entering the study (observed cases).

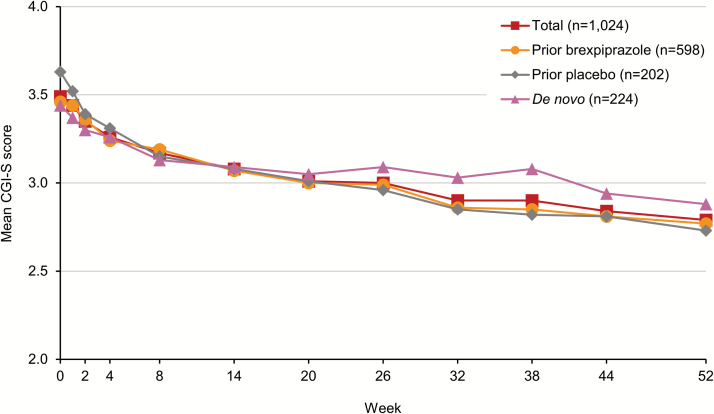

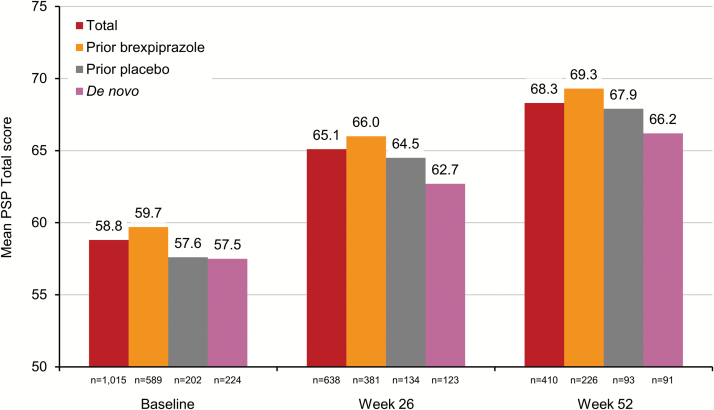

The mean CGI-S score over 52 weeks of open-label brexpiprazole treatment is shown in Figure 3. On average, patients improved by 0.6 points, from mild-to-moderately ill at baseline to mildly ill after long-term treatment with brexpiprazole. Patients improved irrespective of whether they had previously been treated with brexpiprazole or placebo, or were de novo. The mean CGI-I score at week 52 was 2.6, indicating minimal-to-much improvement. Patients also improved over 52 weeks on the PSP Total, with a mean change in score of 7.7 points, to a total of 68.3 points. Patients improved irrespective of prior treatment (Figure 4). Finally, 34.3% of patients met the criteria for PANSS/CGI-I response, and only 4.2% of patients discontinued due to lack of efficacy.

Figure 3.

Mean Clinical Global Impressions – Severity of illness (CGI-S) score over 52 weeks for patients with schizophrenia receiving open-label brexpiprazole 1–4 mg/d, stratified by treatment prior to entering the study (observed cases).

Figure 4.

Mean Personal and Social Performance scale (PSP) Total score over 52 weeks for patients with schizophrenia receiving open-label brexpiprazole 1–4 mg/d, stratified by treatment prior to entering the study (observed cases).

Resource utilization over 52 weeks is shown in supplementary Table 3. A total of 10.5% of patients were hospitalized for exacerbation of symptoms during the study. The average yearly use of health resources, including psychiatrists and other mental health professionals, decreased from baseline to week 52.

Discussion

The primary objective of this 52-week, open-label extension study was to investigate the safety and tolerability of brexpiprazole in adult patients with schizophrenia. The results indicate that long-term treatment with brexpiprazole at flexible doses of 1–4 mg/d is generally well tolerated. The proportion of patients who discontinued the study due to TEAEs was low: 14.6% during the open-label brexpiprazole treatment phase. The most frequently reported TEAE was schizophrenia, and the most frequently reported TEAEs leading to withdrawal were schizophrenia and psychotic disorder, reflecting a worsening of the underlying disease state in this patient population, which is generally observed in long-term schizophrenia studies (Kasper et al., 2003; Cutler et al., 2017; Durgam et al., 2017). Whereas other D2 partial agonists (aripiprazole and cariprazine) are associated with activating TEAEs such as akathisia, insomnia, and anxiety (Chrzanowski et al., 2006; Cutler et al., 2017; Durgam et al., 2017), this does not appear to be the case for brexpiprazole, even in the long term. For example, in a 52-week, open-label study of aripiprazole in stable schizophrenia, insomnia, and anxiety had incidences of 23.8% and 9.9%, respectively (Chrzanowski et al., 2006), compared with 8.6% and 2.2%, respectively, in the present brexpiprazole study. This is supported by an open-label, randomized, exploratory study in acute schizophrenia (n=97), in which aripiprazole was associated with a greater incidence of EPS-related TEAEs than brexpiprazole (30.3% vs 14.1%), predominantly akathisia (21.2% vs 9.4%) (Citrome et al., 2016).

The safety and tolerability results of the present study are generally similar to those observed in prior short- and long-term studies of brexpiprazole in schizophrenia (Correll et al., 2015; Kane et al., 2015; Fleischhacker et al., 2017). No safety concerns with brexpiprazole were noted in the adverse event profile, laboratory test values, ECG, weight, or vital sign parameters. The mean overall weight gain in the present study was 1.3 kg in patients who completed 26 weeks of treatment and 2.1 kg in patients who completed 52 weeks of treatment, consistent with the previous long-term study, Equator, in which a mean weight increase of 0.8 kg was observed in the stabilization phase, and a mean weight decrease was observed in the maintenance phase (Fleischhacker et al., 2017). The incidence of ≥7% body weight increase in the present study was 18.6%, higher than that observed in the stabilization phase of Equator (11.3%; Fleischhacker et al., 2017) but generally on the low side compared with incidences reported in long-term, open-label studies with other second-generation antipsychotics (Chrzanowski et al., 2006; Citrome et al., 2014; Cutler et al., 2017; Durgam et al., 2017). In this regard, brexpiprazole is similar to aripiprazole, which has shown a low propensity for weight gain in the long-term treatment of schizophrenia (Chrzanowski et al., 2006).

It is worth noting that brexpiprazole is also well tolerated when used as an adjunctive treatment by patients with major depressive disorder and inadequate response to antidepressants (Nelson et al., 2016).

Current antipsychotics are limited by adverse events including EPS and activating side effects (akathisia, restlessness, agitation, anxiety, insomnia), sedation, weight gain, metabolic side effects, orthostatic hypotension, and elevated prolactin levels (Correll, 2011; Leucht et al., 2013; Citrome, 2017). There is heterogeneity among different second-generation antipsychotics with regard to activating and sedating adverse events, with some agents being primarily activating, some being primarily sedating, and some displaying the potential for both activating and sedating properties (Citrome, 2017). A recent analysis of absolute risk increase with second-generation antipsychotics in schizophrenia found that only brexpiprazole and paliperidone were neither activating nor sedating (Citrome, 2017). Weight gain is also a problem with the majority of antipsychotics; a comprehensive meta-analysis conducted prior to the availability of brexpiprazole data reported that almost all antipsychotics were associated with increased body weight, and that only amisulpride, aripiprazole, and ziprasidone could be considered weight neutral (Bak et al., 2014). In addition to weight gain, metabolic side effects such as elevated lipids, glucose, and prolactin are a serious concern with some second-generation antipsychotics (Rummel-Kluge et al., 2010; Leucht et al., 2013). Thus, the introduction of brexpiprazole may provide an additional, well-tolerated treatment option in schizophrenia.

The present study investigated efficacy as a secondary endpoint. Long-term open-label treatment with brexpiprazole was associated with sustained improvement in efficacy measures and functional outcomes. PANSS Total and CGI-S scores indicated a mean improvement from mild-to-moderately ill at baseline to mildly ill over 52 weeks of treatment. The magnitude of improvement in PANSS Total score (12.2 points) was comparable to that observed in the 12- to 36-week stabilization phase of Equator (15.1 points; Fleischhacker et al., 2017). Since the majority of patients in the present study had already received brexpiprazole prior to entry, the observed improvement is in addition to any previous benefit.

Deficits in psychosocial functioning are a core feature of schizophrenia and an important outcome in clinical studies of new antipsychotic agents (Burns and Patrick, 2007). In the present study, patients showed a mean improvement in PSP Total score of 7.7 points over the course of treatment to a total of 68.3 points. This is above the threshold for potentially clinically meaningful response in stabilized patients with schizophrenia (an increase of 4–7 points; Nasrallah et al., 2008) and close to functional remission (a total score of >70 points; Pinna et al., 2013). For rollover patients, this continued improvement in psychosocial functioning over 52 weeks is in addition to that observed in prior studies (Correll et al., 2015; Kane et al., 2015; Fleischhacker et al., 2017).

Baseline efficacy scale scores varied according to prior exposure to brexpiprazole at the start of open-label treatment. Some patients entering the open-label treatment phase of this study had no previous exposure to brexpiprazole, having received placebo in the acute studies (Vector and Beacon). De novo patients, in contrast, were generally not brexpiprazole-naïve at the start of open-label treatment, the majority having received brexpiprazole for 4 weeks during the conversion phase. Similarly, patients who received placebo in the maintenance phase of Equator had previous exposure to brexpiprazole for 12 to 36 weeks during the stabilization phase of Equator. In the present study, the subgroup of patients who previously received placebo had the highest baseline PANSS Total score. De novo patients had the lowest baseline PANSS Total score, the majority having improved on brexpiprazole during the conversion phase prior to open-label treatment. In the open-label phase, treatment benefits were observed in all subgroups, irrespective of prior treatment.

This study is limited by having no comparator and an open-label design; however, the open-label design also increases the real-world relevance of the results. Outcomes may have been influenced by the variation in prior patient exposure to brexpiprazole, since some patients were rolled over from acute studies, and others from a long-term maintenance study. For example, inclusion of patients from Equator (the maintenance study) may have enriched the study population, in part, for those who had previously demonstrated tolerability to brexpiprazole. However, this is also a strength of the study: the inclusion of patients who completed the 52-week double-blind maintenance phase of Equator on brexpiprazole means that brexpiprazole safety data are available for more than 2 years of treatment for a limited number of patients. Finally, the design amendments following the early termination of Equator complicated the interpretation of the results, albeit for a minority of patients.

In conclusion, this open-label study showed that treatment with brexpiprazole 1–4 mg/d (flexibly dosed) was generally well tolerated for up to 52 weeks in patients with schizophrenia. No unexpected safety or tolerability issues emerged, and the safety profile was consistent with other brexpiprazole studies in schizophrenia. Furthermore, open-label treatment with brexpiprazole 1–4 mg/d was associated with continued improvement in efficacy measures and functional outcomes in the long term.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology online.

Statement of Interest

Andy Forbes, Mary Hobart, John Ouyang, Lily Shi and Stephanie Pfister are full-time employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization Inc. Mika Hakala is a full-time employee of H. Lundbeck A/S.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Writing support was provided by Chris Watling, PhD, assisted by his colleagues at Cambridge Medical Communication Ltd (Cambridge, UK).

This work was supported by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization Inc. (Princeton, NJ, US) and H. Lundbeck A/S (Valby, Denmark).

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2000)Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed, text revision (DSM-IV-TR®). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bak M, Fransen A, Janssen J, van Os J, Drukker M(2014)Almost all antipsychotics result in weight gain: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 9:e94112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes TR.(1989)A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry 154:672–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns T, Patrick D(2007)Social functioning as an outcome measure in schizophrenia studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 116:403–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrzanowski WK, Marcus RN, Torbeyns A, Nyilas M, McQuade RD(2006)Effectiveness of long-term aripiprazole therapy in patients with acutely relapsing or chronic, stable schizophrenia: a 52-week, open-label comparison with olanzapine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 189:259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citrome L.(2012)Oral antipsychotic update: a brief review of new and investigational agents for the treatment of schizophrenia. CNS Spectr 17(Suppl 1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citrome L.(2013)A review of the pharmacology, efficacy and tolerability of recently approved and upcoming oral antipsychotics: an evidence-based medicine approach. CNS Drugs 27:879–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citrome L.(2017)Activating and sedating adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia and major depressive disorder: absolute risk increase and number needed to harm. J Clin Psychopharmacol 37:138–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citrome L, Weiden PJ, McEvoy JP, Correll CU, Cucchiaro J, Hsu J, Loebel A(2014)Effectiveness of lurasidone in schizophrenia or schizoaffective patients switched from other antipsychotics: a 6-month, open-label, extension study. CNS Spectr 19:330–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citrome L, Ota A, Nagamizu K, Perry P, Weiller E, Baker RA(2016)The effect of brexpiprazole (OPC-34712) and aripiprazole in adult patients with acute schizophrenia: results from a randomized, exploratory study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 31:192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU.(2011)What are we looking for in new antipsychotics?J Clin Psychiatry 72(Suppl 1):9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Skuban A, Ouyang J, Hobart M, Pfister S, McQuade RD, Nyilas M, Carson WH, Sanchez R, Eriksson H(2015)Efficacy and safety of brexpiprazole for the treatment of acute schizophrenia: a 6-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 172:870–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler AJ, Durgam S, Wang Y, Migliore R, Lu K, Laszlovszky I, Németh G(2017)Evaluation of the long-term safety and tolerability of cariprazine in patients with schizophrenia: results from a 1-year open-label study. CNS Spectr. May 8:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S1092852917000220. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durgam S, Greenberg WM, Li D, Lu K, Laszlovszky I, Nemeth G, Migliore R, Volk S(2017)Safety and tolerability of cariprazine in the long-term treatment of schizophrenia: results from a 48-week, single-arm, open-label extension study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 234:199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischhacker WW, Hobart M, Ouyang J, Forbes A, Pfister S, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Sanchez R, Nyilas M, Weiller E(2017)Efficacy and safety of brexpiprazole (OPC-34712) as maintenance treatment in adults with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 20:11–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W.(1976)ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology, revised. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J, Glenthoj B, Gattaz WF, Thibaut F, Möller HJ, WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Schizophrenia (2013)World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 2: update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects. World J Biol Psychiatry 14:2–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane JM, Skuban A, Ouyang J, Hobart M, Pfister S, McQuade RD, Nyilas M, Carson WH, Sanchez R, Eriksson H(2015)A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, controlled phase 3 trial of fixed-dose brexpiprazole for the treatment of adults with acute schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 164:127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper S, Lerman MN, McQuade RD, Saha A, Carson WH, Ali M, Archibald D, Ingenito G, Marcus R, Pigott T(2003)Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole vs. haloperidol for long-term maintenance treatment following acute relapse of schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 6:325–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA(1987)The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 13:261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecrubier Y, Perry R, Milligan G, Leeuwenkamp O, Morlock R(2007)Physician observations and perceptions of positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia: a multinational, cross-sectional survey. Eur Psychiatry 22:371–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, McGlashan TH, Miller AL, Perkins DO, Kreyenbuhl J, American Psychiatric Association, Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines (2004)Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. 2nd ed Am J Psychiatry 161:1–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S, Tardy M, Komossa K, Heres S, Kissling W, Salanti G, Davis JM(2012)Antipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 379:2063–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Örey D, Richter F, Samara M, Barbui C, Engel RR, Geddes JR, Kissling W, Stapf MP, Lässig B, Salanti G, Davis JM(2013)Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 382:951–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Sugino H, Akazawa H, Amada N, Shimada J, Futamura T, Yamashita H, Ito N, McQuade RD, Mørk A, Pehrson AL, Hentzer M, Nielsen V, Bundgaard C, Arnt J, Stensbøl TB, Kikuchi T(2014)Brexpiprazole I: in vitro and in vivo characterization of a novel serotonin-dopamine activity modulator. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 350:589–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder SR, Davis JM, Chouinard G(1997)The effects of risperidone on the five dimensions of schizophrenia derived by factor analysis: combined results of the North American trials. J Clin Psychiatry 58:538–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya A, Valladares A, Lizán L, San L, Escobar R, Paz S(2011)Validation of the Excited Component of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS-EC) in a naturalistic sample of 278 patients with acute psychosis and agitation in a psychiatric emergency room. Health Qual Life Outcomes 9:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, Pioli R(2000)Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand 101:323–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah HA.(2008)Atypical antipsychotic-induced metabolic side effects: insights from receptor-binding profiles. Mol Psychiatry 13:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah H, Morosini P, Gagnon DD(2008)Reliability, validity and ability to detect change of the Personal and Social Performance scale in patients with stable schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 161:213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JC, Zhang P, Skuban A, Hobart M, Weiss C, Weiller E, Thase ME(2016)Overview of short-term and long-term safety of brexpiprazole in patients with major depressive disorder and inadequate response to antidepressant treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rev 12:278–290. [Google Scholar]

- Owen MJ, Sawa A, Mortensen PB(2016)Schizophrenia. Lancet 388:86–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna F, Tusconi M, Bosia M, Cavallaro R, Carpiniello B, Cagliari Recovery Group Study (2013)Criteria for symptom remission revisited: a study of patients affected by schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. BMC Psychiatry 13:235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Currier GW, Melvin GA, Greenhill L, Shen S, Mann JJ(2011)The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry 168:1266–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rummel-Kluge C, Komossa K, Schwarz S, Hunger H, Schmid F, Lobos CA, Kissling W, Davis JM, Leucht S(2010)Head-to-head comparisons of metabolic side effects of second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 123:225–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson GM, Angus JWS(1970)A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 212:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.